95 theses

Martin Luther's 95 theses - in the Latin original Disputatio pro declaratione virtutis indulgentiarum ( disputation to clarify the power of indulgences ), in early German prints Propositiones gegen das Ablas - in which he speaks out against the abuse of indulgences and especially against the commercial trade in letters of indulgence were pronounced on October 31, 1517 as an attachment to a letter to the Archbishop of Mainz and Magdeburg , Albrecht von Brandenburg, first put into circulation. Since Albrecht of Brandenburg did not comment, Luther passed the theses on to a few acquaintances, including Wilhelm and Konrad Nesen , who published them a short time later without his knowledge and thus made them the subject of public discussion throughout the empire.

The historicity of the posting of theses, in which Luther is said to have nailed his 95 theses to the door of the castle church in Wittenberg on Wednesday, October 31, 1517 , is controversial.

The 95 theses

Summary

The document follows the style of disputation theses , as they were common at the time for academic doctorates , and is written in Latin . Based on Jesus' words "Repent" ( Mt 4:17 LUT ), Luther first turned against the fear of purgatory fueled by the church . From thesis no. 21, the indulgence trade forms the focus of his explanations. He describes indulgence as “good business” (No. 67), but denies it any power to “take away even the slightest venial sin” (No. 76). In No. 81 “subtle questions of the laity” are announced, which turn out to be rhetorical questions , for example No. 86: “Why does the Pope , who is richer today than the richest Crassus , prefer to build at least the one Church of St. Peter from ? his own money than that of the poor believers? ”It concludes with an appeal to Christians“ that they seek to follow their head Christ through punishment, death and hell and that they would rather trust to go through many tribulations into the kingdom of heaven than into to calm down false spiritual security ”.

Content of the theses in detail

- 1: Since our Lord and Master Jesus Christ says “Repent” and so on (Matt. 4:17), he wanted the whole life of believers to be repentant.

- 2: This word cannot refer to penance as a sacrament - d. H. of confession and satisfaction - administered by the priestly office.

- 3: It does not only refer to an internal repentance, indeed there would be no such repentance at all if it did not bring about various works to the outside world to kill the flesh.

- 4: Therefore, the punishment remains as long as the hatred of oneself - that is the true penance of the heart - persists, i.e. until the entrance into the kingdom of heaven.

- 5-6: The Pope can only issue punishments that he himself has imposed.

- 7: God only issues punishments to those who submit to the Pope (God's representative on earth).

- 8–9: The church regulations on penance and the issuance of punishments apply only to the living, not to the deceased.

- 10–13: A penalty may not be pronounced for the time after death.

- 14: The lower the belief in God, the greater the fear of death.

- 15-16: This fear alone characterizes purgatory as a place of purification from heaven and hell.

- 17–19: It is certain that those who have died in purgatory can no longer change their relationship with God.

- 20–24: The indulgence preachers are wrong when they say: "All punishment is waived."

- 25: The same power that the Pope has with regard to purgatory in general, every bishop and every pastor has in his area of work.

- 26–29: The Pope achieves forgiveness in purgatory through intercession, but the preachers of indulgence are wrong when they promise forgiveness for money. This increases the income of the church, but intercession depends solely on God's will.

- 30–32: No one can surely obtain forgiveness through indulgence.

- 33–34: The Pope's indulgence is not a gift from God in which people are reconciled to God, but only a forgiveness of the punishments imposed by the Church.

- 35–40: No one can receive forgiveness without repentance; but those who really repent are entitled to complete forgiveness - even without a paid letter of indulgence.

- 41–44: Buying the letters of indulgence has nothing to do with charity, and it only partially exempts you from the penalty. Good works of charity such as support for the poor or those in need are more important.

- 45–49: Anyone who does not help a needy but instead buys indulgences earns the wrath of God.

- 50–51: If the Pope knew the extortion methods used by the preachers of indulgence, he would not use them to build St. Peter's Basilica in Rome.

- 52–55: No salvation can be expected due to a letter of indulgence. It is wrong to talk about indulgences longer in a sermon than about God's Word.

- 56–62: The treasure of the church, from which the Pope distributes indulgences, has not been identified precisely enough, nor has it been recognized by the people of Christ. But grace for the inner man works without a Pope through Jesus Christ. The true treasure of the church is the gospel of the glory and grace of God.

- 63–68: The indulgence is the net with which one now catches the wealth of those who have haves.

- 69–74: The bishops and pastors should watch the indulgence preachers so that they do not preach their own opinions instead of the papal ones.

- 71–74: Whoever speaks against the truth of the apostolic indulgence is rejected and cursed. Rather, the Pope wants to hurl the banish beam against those who, under the pretext of indulgence, contemplate deceit with regard to holy love and truth.

- 75–76: Indulgence cannot forgive serious or minor sins.

- 77–78: The Pope, just like the apostle Simon Peter, can receive abilities from God, as it is written in 1 Cor 12 : 1–11 EU .

- 79–81: It is a blasphemy to equate the indulgence cross with the Pope's coat of arms in churches with the cross of Jesus Christ . Anyone who delivers such cheeky sermons can endanger the Pope's reputation, for example through subtle questions from the laity:

- 82: Why doesn't the Pope clear purgatory for everyone?

- 83: Why do funeral masses for the dead continue when it is not allowed to pray for the ransomed?

- 84: Why Can an ungodly Man forgive sins for money?

- 85: Why are the penal statutes, which have practically been abolished, still being replaced with money?

- 86: Why doesn't the rich Pope at least build St. Peter's Basilica with his money?

- 87: What does the Pope release for those who, through perfect repentance, are entitled to total remission of sins?

- 88: Why does he forgive all believers only once a day and not a hundred times a day?

- 89: Why does the Pope keep previous letters of indulgence?

- 90-93: If indulgences were preached according to the Pope's view, these objections would be resolved. So get rid of these false indulgence preachers.

- 94–95: Christians should be encouraged to follow Jesus Christ and not let them buy false spiritual security through letters of indulgence.

Lore

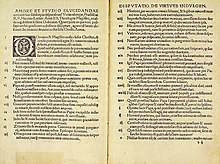

Neither Luther's handwriting of the theses nor a Wittenberg print has survived. The 95 theses he presented may have come from Johann Gronenberg's press as a single-sheet print . A single-sheet print (folio sheet in two columns) of the Latin text, apparently commissioned by Luther himself, was published by Jacob Thanner in Leipzig as early as 1517 . Although the Leipzig printer Jacob Thanner numbered the theses consecutively with Arabic numerals, but he was wrong repeatedly, the number 42 was in front of the 24th thesis, after the 26th thesis the number continued with 17. The second part of a thesis was given its own number twice - Luther's 55th insight appeared as the 45th and 46th and no. 83 as the 74 and 75. In the end, the Leipzig print of the 95 theses only came to 87 as the highest number.

Another single-sheet print was probably published in December by Hieronymus Höltzel († approx. 1532) in Nuremberg , a book edition (four sheets in quart) by Adam Petri in Basel: Disputatio pro declaratione virtutis indulgentiarum . Hieronymus Höltzel from Nuremberg apparently had problems with higher numbers - he lined up the numbers 1 to 25 three times and a fourth block from 1 to 20.

While the Leipzig print erroneously counts 87 theses in Arabic numerals, the Nuremberg poster print and the Basel quarto print count the 95 theses in groups of three times 25, followed by 20 theses at the end; it is not known to whom this classification can be traced back.

Translations into German

Probably before Christmas 1517, the Nuremberg-based Kaspar Vorteilel translated Luther's 95 theses into German, as mentioned in a letter from Christoph Scheurl dated January 8, 1518. This earliest German translation to be dated is only documented by reports, but has not become known bibliographically. "Despite the lack of bibliographical evidence of the existence of a print of the utilitarian version, the idea of its existence haunts the literature."

The oldest verifiable anonymous print is from 1545 (reprint Berlin 1892). This is followed by the translation in 1555 by Justus Jonas the Elder, first in 1555 in Jena near Rödinger in the volume The First Part of All Books and Writings of the Blessed Mans Doct: Mart: Lutheri , then as the ninth part of the books of the venerable Mr. D. Martini Lutheri , Printed in 1557 by Hans Lufft in Wittenberg - published by Philipp Melanchthon and titled against the Ablas in the Propositiones Lutheri directory . The translation is not considered to be very faithful to the original.

There is also a manuscript with a partial translation in the Eichstätt University Library (Cod. St 695), written between 1518 and 1525.

distribution

"The message itself became known to a broad readership not through the Latin theses and their interpretations in the Resolutiones de indulgentiarum virtute published in the spring of 1518 , but through the German-language sermon of indulgence and grace [alternatively also: freedom of the sermon concerning papal indulgence and grace ] who made Luther's real breakthrough as a writer. No fewer than 15 High German editions of this publication as well as one Low German appeared in 1518, and a further nine in the following two years. "

Significance, requirements and effects

As early as 1456, papal financial practices were disapproved of at all diets in the Holy Roman Empire . But not only did the princes complain about this, their criticism was also directed against the attempt by the clerical jurisdiction to extend their jurisdiction to secular affairs. In 1457, the imperial estates brought the complaints or gravamina of the German nation , Gravamina nationis germanicae , before them. They were of considerable importance in creating an anti-papal mood that was directed against the influence of the Roman Catholic Church and the privileges it claims. In the "100 gravamina nationis germanicae" (first printed in Nuremberg in 1523 in German and Latin), which were presented at the Nuremberg Diet of 1522 , the criticism of the Roman Church in the Holy Roman Empire had already become a vehement anti-curialism, the significantly promoted the progress of the Reformation. The complaints were already in 1522 to Pope Hadrian VI. has been sent. It was above all the clergy princes, the prince-bishops , who complained against the centralization of ecclesiastical affairs in Rome . This concerned, for example, the financial contributions that most of the bishops had to pay to have a benefice granted them by the Curia . Martin Luther and the reformers were able to build on this anti-papal mood ; thus Luther's 95 theses fell on a kind of prepared ground.

The publication of Luther's 95 theses was one of the most significant events in the early modern period with an unpredictable long-term effect. Since the spring of 1517, Luther experienced more and more frequently that the Wittenbergers stayed away from confession and instead went to the towns of Jüterbog and Zerbst , which are located in Stiftsmagdeburg or Anhalt , to protect themselves, but also deceased relatives, from sins and penalties by purchasing letters of indulgence to buy free. In fact, the abuse of indulgences was one of Luther's main criticisms. Half of the income from the indulgence trade was used to build St. Peter's Basilica in Rome , while Archbishop Albrecht and the indulgence preachers shared the other half. The bishop needed the income to pay off his debts to the Fuggers . So the theses were an attack on the papal financial system.

Because Luther's criticism of the indulgence trade stood against a complex background. Albrecht von Brandenburg became archbishop of Magdeburg and administrator of the Halberstadt diocese as early as 1513 at the age of 23 . Since there was a canonical ban on holding more than one bishopric , Albrecht of Brandenburg had to let the Arch and Electorate of Mainz, which was at issue in 1514, decide with a dispensation from the Holy See in Rome . Albrecht's request was settled in his favor, but it was stated that he would have to contribute a sum of 21,000 ducats to the construction of St. Peter's Basilica. Albrecht borrowed the amount for this from Jacob Fugger . In order to settle these debts, the proceeds from the sale of indulgences of the Dominican Johann Tetzel were to be used. This was an attack on the indulgence trade in the vicinity of the Holy Roman Empire, but also an indirect attack on the Fugger's finance house in Augsburg.

In addition, Emperor Maximilian died in January 1519, leaving his grandson Karl I , the Duke of Burgundy and King of Spain, the Habsburg hereditary lands with the Burgundian neighboring countries and a controversial claim to the Roman-German imperial throne. In order to politically secure his demands on the House of Habsburg (more than 170,000 guilders), Jakob Fugger again supported the aspirant to the throne in his election as Roman-German king. In addition to Karl , Franz I of France and Henry VIII of England also applied for successor as Roman-German King and Emperor . At the end of the election campaign, the Curia also brought Elector Friedrich von Sachsen - who held a protective hand over Luther - into play, but Karl's brother Ferdinand was also considered as a candidate at times. Because for the Papal States of the upcoming change in the emperor meant the Holy Roman Empire a change in the political geography . In this way, the territorial domination of the Habsburgs could limit the Vatican's room for maneuver. In this context, the elector Friedrich of Saxony was now in a play of forces around the newly appointed emperor.

In the actual competition with each other were Charles and Franz I. This competition exceeded in its intensity all previous and subsequent elections of this kind. Both candidates represented the imperial idea of a "universal monarchy", monarchia universalis , which should overcome the national monarchical separation of Europe. The electoral college consisted of three ecclesiastical (the archbishops of Mainz , Cologne and Trier) and four secular princes (the King of Bohemia , the Duke of Saxony , the Margrave of Brandenburg and the Count Palatine near the Rhine). In this very difficult situation for Karl, the financial strength of the businessman Jakob Fugger decided in favor of the Habsburgs. Fugger transferred the sum of 851,918 guilders to the seven electors , whereupon Karl was unanimously elected Roman-German king in his absence on June 28, 1519 in Frankfurt am Main .

The theses published in response to Johann Tetzel's sermons of indulgence had an eminent impact on almost all social, cultural and political structures - something that Luther himself could hardly have anticipated. The need for reform of the church and thus the church constitution has long been an urgent problem. The publication of his theses was intended as a basis for discussion for expert theologians. However, the theses became independent very quickly and were often reprinted as handouts. Instead of the hoped-for discussion, there was initially a trial of heretics in 1518 and finally even an excommunication .

The effect of Luther's thoughts, however, continues to this day. The theses formulate a criticism of the conditions then prevailing on the basis of the Bible. Luther explains the indulgence trade in the theses for the work of man because the Bible does not contain any basis for this Roman Catholic concept. Luther initially allows the indulgence for punishments imposed by the church to still apply; but his criticism is directed strictly against the false security of salvation that stems from incorrect handling of indulgences. The Pope is not exempt from the criticism either: Luther begins his public criticism of the institution of the papacy here - a spiritual explosive device which then unfolded its full force in the next few years and decades and ultimately led to the schism , to the division of the Western Church .

Luther's sovereign, Elector Friedrich III. von Sachsen, supported him in this stance because he, too, did not want to tolerate the outflow of these funds from his own territory to Rome.

Authenticity of the theses

The authenticity of the theses is controversial. The existence of the initially handwritten thesis paper is beyond doubt. One copy went to Archbishop Albrecht of Mainz , who was also Archbishop of Magdeburg and as such was responsible for Wittenberg. Additional copies went to other religious dignitaries of the empire and one - in response to the instructions - to the drain and Sellers John Tetzel , but which it did not respond. Without his consent, a public disputation would have been viewed as a serious provocation. It is unlikely that Luther intended this or was unaware of such a possible consequence.

The posting of the theses is mentioned for the first time by Luther's secretary Georg Rörer , who in 1540 (or 1544) reported in an editing note for the New Testament - which was only found in 2006 - of the announcement of the theses on the doors of several Wittenberg churches: “On the eve of the Lord's All Saints' Day In 1517, Doctor Martin Luther posted theses on indulgences on the doors of the Wittenberg churches. ”The find suggests that the theses were published in several Wittenberg churches at the same time. However, the evidential value of the document is controversial and it is unlikely that Rörer was an eyewitness to the posting of the theses.

Until Luther's death in 1546, the posting of the theses was not mentioned in any Reformation publication. It was popularized only afterwards, in particular by Philipp Melanchthon , who first mentioned it in 1547 in the preface to the second volume of his edition of Luther's works. This was intended as a challenge to one of the usual academic disputations. Melanchthon was not called to Wittenberg until 1518 and therefore cannot have been an eyewitness to such an event. Starting with Melanchthon, the posting of the theses developed into a founding myth of the Reformation.

The event of the posting of the theses has been questioned by the Catholic church historian Erwin Iserloh since 1961 . His Protestant colleague Heinrich Bornkamm , on the other hand, said that it was in line with the usual practice of academic disputations in Wittenberg to post the theses publicly at the castle church as a university church , because it also served as the maximum auditorium for disputations and doctorates. The church historian Kurt Aland also considers the events to be authentic.

Gerhard Prause summarized in 1966 in his book Nobody laughed at Columbus. Falsifications and lies in history rectified the history of the 95 theses and stated that the attack on the 95 theses was a myth that went back to a misinterpretation of a text by the only known contemporary witness Johannes Agricola at the time. They read me teste ( Latin “as I can testify”) instead of modeste (“in a modest way”). According to Prause, Agricola wrote: "In 1517, Luther in Wittenberg on the Elbe presented certain sentences for the disputation according to the old university custom, but in a modest way and without wanting to insult or insult anyone".

Possibly this view has to be revised by the note of the Luther secretary Georg Rörer . Historians Benjamin Hasselhorn and Mirko Gutjahr again spoke out in favor of authenticity in 2018 .

Current reception

The posting of the theses is interpreted in many ways up to the present day and has been processed in various films and books. Among other things, he contributed to the title of the American theological-satirical magazine The Wittenburg Door .

literature

- Kurt Aland : The reformers: Luther, Melanchthon, Zwingli, Calvin. 4th, revised edition. Gütersloher Verlagshaus, Gütersloh 1986, ISBN 3-579-05204-7 .

- Fritz Bellmann, Marie Luise Harksen, Roland Werner (eds.): The monuments of Lutherstadt Wittenberg. Hermann Böhlau Verlag, Weimar 1979.

- Heinrich Bornkamm : Theses and theses posting of Luther: Events and meaning. Töpelmann, Berlin 1967.

- Benjamin Hasselhorn , Mirko Gutjahr: fact! The truth about Luther's posting of the theses. Evangelische Verlagsanstalt, Leipzig 2018, ISBN 978-3-374-05638-5 ( publisher presentation ).

- Erwin Iserloh : Luther between reform and reformation: the theses were not posted. 3rd, revised and expanded edition by the 8th chapter. Aschendorff, Münster 1968.

- Martin Luther : "For the love of truth ..." The 95 theses . Facsimile of the original edition (Basel 1517) and translation into German, with contributions by Reinhard Feldmann and Klaus-Rüdiger Mai , edited by Thomas A. Seidel on behalf of the International Martin Luther Foundation . Westhafen Verlag, Frankfurt am Main 2017, ISBN 978-3-942836-13-5 .

- Joachim Ott, Martin Treu (Ed.): Fascination Theses Attack - Fact or Fiction. Leipzig 2008, ISBN 978-3-374-02656-2 .

- Gerhard Prause : Nobody laughed at Columbus - corrected the falsifications and lies of history. Econ, Düsseldorf 1966, ISBN 3-430-17581-X .

- Helga Schnabel-Schüle (Ed.): Reformation. Historical and cultural studies manual. Metzler, Heidelberg 2017, ISBN 978-3-476-02593-7 , pp. 298-310.

- Manfred Schulze : Theses posting . In: Religion in Past and Present 4th edition, Volume 8. Mohr, Tübingen 2005, ISBN 3-16-146948-8 , Sp. 357 f.

- Uwe Wolff : Iserloh. The theses were not posted (= Studia Oecumenica Friburgensia. Volume 61). Institute for Ecumenical Studies at the University of Friborg Switzerland, Friedrich Reinhardt Verlag, Basel 2013, ISBN 978-3-7245-1956-0 .

Web links

- The 95 theses in German, published by Philipp Melanchthon in 1557

- The 95 theses at the Evangelical Church of Germany

- The 95 theses in the Gutenberg-DE project

- Matthias Heine (October 31, 2017): 95 reasons why no one has escaped Martin Luther to this day ( memento from March 26, 2018 in the Internet Archive ) . In: The world . Archived from the original on March 26, 2018. Retrieved March 26, 2018.

Individual evidence

- ↑ a b c d http://www.luther.de/leben/anschlag/95thesen.html

- ↑ Michaela Scheibe: 95 or 87? Martin Luther's disputation theses to clarify the power of indulgences. Berlin State Library - Prussian Cultural Heritage, October 31, 2016 [1]

- ↑ see: Franz von Soden (Hg): Christoph Scheuerl's Briefbuch. Potsdam 1872, Vol. 2, No. 160, p. 43.

- ↑ Karl Heinz Keller: On an early vernacular translation of 30 of Luther's 95 theses. In: Developments and Holdings - Bavarian Libraries in Transition to the 21st Century. Harrassowitz, Wiesbaden 2003, p. 175.

- ↑ VD 16 L3323.

- ↑ VD 16 L3333.

- ↑ see Karl Heinz Keller: On an early vernacular translation of 30 of Luther's 95 theses .

- ↑ Johannes Schilling ( Memento from November 11, 2014 in the Internet Archive ). A listing of the issues at: Friedrich Kapp : History of the German book trade up to the seventeenth century . Verlag des Börsenverein der Deutschen Buchhandels, Leipzig 1886, vol. 1, p. 412 .

- ↑ Albrecht of Brandenburg, succeeding Uriel von Gemmingen on

- ^ Lyndal Roper: Luther. The man Martin Luther. The biography. S. Fischer, Frankfurt am Main 2016, ISBN 978-3-10-066088-6 , p. 13.

- ↑ Helga Schnabel-Schüle : Reformation. Historical and cultural studies manual. Metzler, Heidelberg 2017, ISBN 978-3-476-02593-7 , p. 5.

- ↑ Martin Treu: To the doors of the Wittenberg churches - news on the debate about the posting of the theses .

- ↑ Latin original: “Anno Do [m] ini 1517 in profesto o [mn] i [u] m Sanctoru [m] p (…) Wite [m] berge in valuis templorum propositae sunt pro [positiones] de Indulgentiis a D [ octore] Mart [ino] Luth [ero] ”.

- ^ W. Marchewka, M. Schwibbe, A. Stephainski: Zeitreise. 800 years of life in Wittenberg / Luther. 500 years of the Reformation . Edition Zeit Reise, Göttingen 2008, p. 39 .

- ↑ DFG project "Processing the estate of Georg Rörer (1492–1557) in the Thuringian University and State Library Jena (ThULB) ..." ( Memento from January 19, 2012 in the Internet Archive )

- ↑ see Erwin Iserloh: Luther between reform and reformation. Munich 1966.

- ↑ Benjamin Hasselhorn , Mirko Gutjahr: fact! The truth about Luther's posting of the theses. Evangelische Verlagsanstalt, Leipzig 2018, ISBN 978-3-374-05638-5 .

- ↑ Historians: Luther's posting of the theses is a fact. Evangelical Church in Central Germany, October 10, 2018