Alexander III (Russia)

Alexander III ( Russian Александр III ; native Alexander Alexandrovich Romanov , Russian Александр Александрович Романов * February 26, jul. / 10. March 1845 greg. In the Winter Palace , Saint Petersburg , † October 20 jul. / 1. November 1894 greg. In Liwadija- Palast , Crimea ) came from the house of Romanow-Holstein-Gottorp and was Emperor of Russia from 1881 to 1894 .

Alexander III received the title of "peacemaker" (Russian mirotworjez) while he was still alive, because no major war with the great powers occurred during his term of office.

Origin and youth

His Imperial Highness Grand Duke Alexander Alexandrovich Romanov was born on February 26th . / March 10, 1845 greg. Born in the Saint Petersburg Winter Palace . He was the third child and second-born son of the Russian heir to the throne Alexander Nikolajewitsch Romanow and his German wife Marija Alexandrovna (born Marie of Hesse-Darmstadt).

In character, the young Alexander displayed a simple, coarse, and abrupt manner, at times even harsh. He also differed from most of his family members because of his robust build and immense physical strength.

In 1855 his father ascended the Russian imperial throne as Alexander II . His older brother Nicholas became the new tsarevich, and consequently his upbringing and training at court enjoyed the highest priority. Alexander was assigned relatively little prospects for the throne, and he received an insufficient, superficial training for a grand duke , which was marked by military drill.

As Tsarevich (1865 to 1881)

After the sudden death of his brother in 1865, Alexander became the new heir to the throne. But despite his title, he had little influence on public life and politics, rather he lived in seclusion in the Anitschkow Palace . Aware of his lack of preparation, the family turned to Konstantin Pobedonoszew , a professor at Moscow University , who instructed the Tsarevich in law and political science . Pobedonoszew, who was known for his extreme conservatism , was to exert great influence on Alexander throughout his life.

Alexander accompanied his father on several state visits and got to know numerous heads of state, important heads of government and foreign ministers. Among other things, he visited the World Exhibition in Paris in 1867 and rode in the same carriage with the French Emperor Napoleon III. and his father when he witnessed an assassination attempt on his father. Since the coachman intervened in time, the assassin Berezovski's bullet hit the horse. In addition, in September 1873 he was at the Dreikaisertreffen in Berlin, where he met the German and Austro-Hungarian monarchs and the German Chancellor Otto von Bismarck .

As an officer , the Tsarevich took part in the Russo-Ottoman War in Bulgaria in 1877/78 . At the subsequent Berlin Congress , Bismarck did not support Russia's demands, but appeared as an “ honest broker ”. Alexander was disappointed with the behavior of the German Reich ; for him, the future of Russia was not on the side of the Germans. With this he was more and more at odds with his father, who based his foreign policy on an alliance with Prussia (later the German Reich), while Alexander felt more drawn to France .

However, Bismarck agreed to a compromise negotiated between Russia and Great Britain at the Berlin Congress, according to which Russia was awarded as compensation for the hegemony of the Slavic peoples in the Balkans and for smaller Bulgaria territorial gains in Adjara . This area was under the control of the Ottoman forces at the time of the Berlin Congress . In the dispute over the city of Batumi , he accepted a more Russia-friendly proposal for Batumi to belong to the Russian Empire on the premise that Batumi was declared a free port.

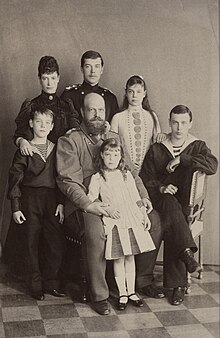

Marriage and offspring

On the deathbed of his brother Nikolai , Alexander promised to marry his fiancée Princess Dagmar of Denmark . On November 9, 1866, the wedding was celebrated in the chapel of the Winter Palace . After her conversion to the Russian Orthodox Church, Dagmar took the name Maria Feodorovna. The connection was described as happy; neither of the two is said to have had extramarital affairs.

The marriage had six children:

- Nikolaus (1868–1918), as Nikolaus II. Emperor of Russia ⚭ Alix von Hessen-Darmstadt

- Alexander (7 June 1869 - 2 May 1870)

- Georgi (1871-1899)

- Xenija (1875–1960) ⚭ Alexander Michailowitsch Romanow

- Michail (1878–1918) ⚭ Natalja Sergejewna Brassowa

- Olga (1882-1960)

Alexander led a very domestic and family life with his Danish wife. Extended summer vacations in the Langinkoski mansion near Kotka on the Finnish coast were an integral part of family life . There the children were immersed in a Scandinavian way of life of relative modesty.

As the ruling emperor (1881 to 1894)

After Alexander's father, Tsar Alexander II, fell victim to a bomb attack by the underground organization Narodnaya Volja (People's Will) on March 13, 1881 , his son followed him as Alexander III. on the throne. The coronation celebrations took place two years later, on May 27, 1883, in Moscow's Cathedral of the Assumption .

Domestic politics

The assassination of Emperor Alexander II followed his successors like a ghost, which is why Alexander III. For security reasons, he and his family moved into the well-guarded, fortress-like castle of Gatchina . As a result of the attack, there were numerous anti-Semitic pogroms against the Jewish population across Russia . In response, the new emperor passed the so-called “May Laws” in 1882, which severely restricted the free exercise and freedom of movement of the Jewish minority .

For Alexander, Russia's strength lay in itself. He believed that his empire had been riddled with anarchist troublemakers and revolutionary agitators that needed to be fought. In 1881, Emperor Alexander founded the Ochrana secret police as an instrument of the fight, locking political opponents in Siberian labor camps . Alexander saw an “infiltration” of society as a further problem, especially with regard to German influence. Russia should be a homogeneous state structure in which ethnic differences in religious and linguistic diversity have to be overcome. In order to achieve this goal, Alexander started a radical policy of Russification , which had to be enforced, especially in Poland and the Baltic States, against stiff resistance from the population. For Alexander saw the pillars of his autocratic rule in the Slavic nation, the Orthodox Church and a unified administration. In his politics he was supported by Konstantin Pobedonoszew, who acted as personal advisor to the tsar and rose to the gray eminence at court. In Alexander's view of rule there was no place for parliamentary institutions and Western European liberalism . He overturned almost all his father's proposals for liberalization, although he could not reintroduce serfdom, centralized the administration and weakened the Zemstvo representatives in the countryside. Gradually he became hostile to all classes in Russia. Again the terror flared up everywhere.

Encouraged by the successful assassination attempt on Alexander II , the underground organization Narodnaya Volja prepared the assassination of Alexander III. in front. The police managed to uncover the scheme and arrest the conspirators, including Alexander Ulyanov , Vladimir Lenin's older brother . Five of the conspirators were hanged in May 1887.

Probably the greatest achievement of Alexander III. During his 13-year rule, the foundation stone was laid for the Trans-Siberian Railway , the longest railway line in the world. This connected the European part of Russia with the Siberian eastern regions and was the emperor's central instrument of rule in these remote regions.

Foreign policy

In terms of foreign policy, Alexander III followed. the traditional policy of the gradual expansion of tsarist rule in Central and East Asia. He wanted to avoid conflicts with other great powers, however, because he was emphatically a man of peace. Alexander did not take the standpoint of "peace at any price," rather he followed the principle that the best way to avoid war is good military preparation.

Although cautious about the German Reich, the traditionally good relationship between the two states only deteriorated towards the end of Alexander's rule. Alexander III concluded the three emperors ' alliance in Berlin in June 1881 with the emperors Wilhelm I of Germany and Franz Joseph I of Austria-Hungary . Russia declared itself neutral in a possible conflict between Germany and France and gained a free hand in the east.

In the years 1881 to 1885, Russian troops occupied the southern part of the Trans-Caspian region, which is in what is now Turkmenistan . At the same time, British troops had been in Afghanistan since the 2nd Anglo-Afghan War . As long as Russian troops were active in southern Transcaspia, there was a risk of confrontation with Great Britain. In this case, the Russian Empire could benefit from the Three Emperor League, which guaranteed the neutrality of the German Empire and Austria-Hungary.

At the same time, Alexander III. a rapprochement with France, partly because of his personal inclinations, but above all Alexander was looking for investors for the expensive Trans-Siberian railway and to finance the burgeoning industrialization . Since France had been isolated by Bismarck for 20 years, this rapprochement could be won over. The open break occurred in 1890 when the German Kaiser Wilhelm II did not extend the reinsurance treaty with Russia. Now the way to a Russian-French alliance was free. A year later, the two governments signed an agreement to consult in the event of a threat to peace - the forerunner of the 1894 partnership .

The attempt of the Cossack Nikolai Aschinow to establish a Russian presence in Sagallo in French Somaliland in 1889 also fell under his rule . However, Alexander soon distanced himself from this project in order not to strain relations with France.

End of life

On the return from a trip to the Caucasus , the emperor and his family were affected by a railway accident on October 17, 1888 (Julian calendar) or October 29, 1888 (Gregorian calendar) near Borki together with his entourage . The court train derailed and fell down a slope. The cause could not be clarified. When the roof of the dining car threatened to fall on the passengers, Alexander is said to have raised the roof with his shoulders until everyone was safe. The imperial family got away with the horror. According to the doctors, this superhuman exertion left permanent damage to his organs.

Six years later, the emperor fell ill with severe kidney disease ( nephritis ), presumably as a result of the long-term consequences of the accident, and died on November 1, 1894 in the Livadija Palace in the Crimea , where he had been on vacation.

His remains were interred in the Peter and Paul Fortress of Saint Petersburg.

In Russia, after the collapse of the USSR, the personality of Alexander III. idealized to a certain extent and mainly used by nationalist circles. On November 18, 2017, President Putin dedicated the monument to Alexander III in Livadia Park in Crimea . a.

literature

- Sylvain Bensidoun: Alexander III: 1881-1894 . Sedes, Paris 1990.

- Edith M. Almedingen: The Romanows. The story of a dynasty. Russia 1613-1917 . Ullstein, Frankfurt am Main 1995, ISBN 3-548-34952-8 .

- Gudrun Ziegler: The gold of the tsars . Heyne, Munich 2000, ISBN 3-453-17988-9 .

Web links

- Literature by and about Alexander III. in the catalog of the German National Library

- Short biography of Alexander III.

- Raphael porcelain service

- Hanns-Martin Wietek: Emperor Alexander III - The beginning of the end

- National Newspaper Library , Hufvudstadsbladet, November 10, 1866, page 1 (Swedish)

Individual evidence

- ↑ In contemporary linguistic usage as well as abroad it remained customary until 1917 to continue speaking of the tsar and has been preserved in the consciousness of posterity. What this affected was not the current dignity of the empire, but the continuation of the specifically Russian reality, in the form of the Moscow tsarist empire, which served as the basis of the new empire. In the 19th century, this led to a conceptual language in literature that was not appropriate to the source and to an outmoded conceptual apparatus in German literature. in: Hans-Joachim Torke: The Russian Tsars, 1547–1917, p. 8; Hans-Joachim Torke: The state-related society in the Moscow Empire , Leiden, 1974, p. 2; Reinhard Wittram: The Russian Empire and its Shape Change, in: Historische Zeitschrift , Vol. 187, H. 3 (Jun., 1959), P. 568-593, P. 569.

- ^ Andreas Künzli: LL Zamenhof (1859-1917). Esperanto, Hillelism (Homaranism) and the "Jewish question" in Eastern and Western Europe . Harrassowitz Verlag, Wiesbaden 2010 p. 34

- ↑ Kai Merten: Among each other, not next to each other. The coexistence of religious and cultural groups in the Ottoman Empire in the 19th century. Paperback 2014, Volume 6 pp. 212–213

- ^ Daniel Schmidt: European peacekeeping. The process of a successful diplomatic conflict resolution using the example of the Berlin Congress in 1878. Federal College for Public Administration, writings on general internal administration. Footnotes on p. 90

- ↑ For better understanding and standardization, only the dates of the Gregorian calendar are given below.

- ↑ Sidney Harcave. Count Sergei Witte and the Twilight of Imperial Russia: A Biography . ME Sharpe, 2004. ISBN 0765614227 . P. 32.

- ↑ a b Sidney Harcave. The Memoirs of Count Witte . ME Sharpe, 1990. ISBN 0765640678 . Pp. 205-207.

| predecessor | Office | successor |

|---|---|---|

| Alexander II |

Emperor of Russia 1881–1894 |

Nicholas II |

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Alexander III |

| ALTERNATIVE NAMES | Александр III (Russian); Romanow, Alexander Alexandrowitsch (maiden name); Романов, Александр Александрович (maiden name, Russian) |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | Russian emperor |

| DATE OF BIRTH | March 10, 1845 |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | Winter Palace , Saint Petersburg |

| DATE OF DEATH | November 1, 1894 |

| Place of death | Livadia Palace , Crimea |