War of the Palatinate Succession

Palatinate War of Succession (1688–1697)

Philippsburg - Koblenz - Walcourt - Bantry Bay - Mainz - Bonn - Fleurus - Beachy Head - Boyne - Staffarda - Québec - Mons - Cuneo - Leuze - Aughrim - Barfleur / La Hougue - Namur 1 - Steenkerke - Lagos - Neerektiven - Marsaglia - Charleroi - Torroella - Camaret - Texel - Sant Esteve d'en Bas - Gerona - Dixmuyen - Namur 2 - Brussels - Ath - Cartagena - Barcelona

The War of the Palatinate Succession (1688–1697), also known as the Orléans War , the War of the Augsburg Alliance , the War of the Great Alliance or the Nine Years War , was a conflict provoked by the French King Louis XIV in order to have the Holy Roman Empire recognize his acquisitions as part of his To achieve reunion policy .

overview

Disputes about the inheritance of Elector Charles II of the Palatinate served as a pretext . A similar pretext was the conflict over the occupation of the Cologne archbishopric ( Cologne diocese dispute ).

The Vienna Great Alliance was formed against Louis XIV, among others from England , the Netherlands , Spain , Savoy and the Holy Roman Empire. Within the kingdom next to the playing Imperial Army and territorial quotas in particular, some armored imperial estates and the war-affected Done Middle Reichskreise an important role.

The war initially took place mainly in the Electoral Palatinate , in large parts of southwest Germany and on the Lower Rhine. In response to the advancing Allies, French troops systematically devastated the Palatinate and neighboring areas. Numerous villages, castles, fortresses, churches and entire cities such as Speyer , Mannheim and Heidelberg were destroyed in the Palatinate, Kurtrier and Württemberg .

The war spread in Europe to the theaters of war in the Netherlands, Italy and Spain. The Glorious Revolution and the accession to the throne of Wilhelm III were related to this . of Orange and the Jacobite backlash in the British Isles. Emperor Leopold I also fought against the Ottomans in the Great Turkish War .

On the mainland, the focus of the fighting shifted to the Netherlands in the course of the war. The warfare was characterized by a tactic of attrition, by tactical maneuvers of armies and sieges. Major battles were relatively rare. In addition, the naval powers England and the Netherlands fought against France at sea and in the colonies. In addition to large naval operations, the pirate war played an important role on both sides. Overall, the French were able to assert themselves against the opposing superiority. There was no clear winner.

Finally, Ludwig XIV and Wilhelm III agreed. to a peace treaty that the Reich had to join. In the Peace of Rijswijk , Louis XIV had to vacate some conquered areas such as the Duchy of Lorraine and part of the reunited territories. In contrast , Alsace and Strasbourg, which were occupied by France in 1681, remained with France.

Terminology

There are different names for war. French historiography prefers the term of the Guerre de la Ligue d'Augsbourg after the Augsburg Alliance . According to Heinz Duchhardt, this term overestimates the significance of this district association, which was created as a defensive alliance . The term Palatinate War of Succession is also problematic because Louis XIV did not question the succession in the Palatinate as such, but because it was about certain rights and allodes to which Philippe I. de Bourbon, duc d'Orléans , raised claims. Hence the conflict was also called the Orléans War . The term Nine Years War , which is used in English, is neutral . The term “ War of the Great Alliance ” is used less often .

prehistory

French influence in the empire

Louis XIV derived from the Peace of Westphalia a right of intervention for the guarantee power France and pursued an active policy in the empire. This manifested itself in the Rhenish Confederation and in the search for allies among the imperial estates. France took on the role of arbitrator in the dispute between individual estates, for example between Kurmainz and the Electoral Palatinate (1658) or in the wildcat dispute (until 1667).

The war of devolution of 1667/68 against the Spanish Netherlands also affected the empire because it involved parts of the Burgundian empire . However, the empire or the imperial estates offered little resistance. The Triple Alliance took over this from England, the Netherlands and Sweden in 1668 .

For fear of the overpowering Habsburg domination in the empire, an alliance with France appeared to many imperial estates as a logical consequence, especially in the 1660s. As a result of France’s continued expansion policy, Louis XIV increasingly lost its prestige. The occupation of Lorraine (1670) and the triggering of the Dutch War contributed to this. In this the majority of the estates stood on the side of the Netherlands and the emperor against Louis XIV.

Reunion policy, Ottoman war and repeal of the Edict of Nantes

The reunion policy of Louis XIV contributed to the fact that most of the imperial estates - with exceptions such as the Electorate of Brandenburg - moved back to the imperial side. With reference to a vague article of the Peace of Westphalia on Alsace, Louis XIV claimed imperial territories and enforced French rule in part with the help of the so-called Reunionskammern as a basis for legitimation. In 1681 he annexed the imperial city of Strasbourg without any legal claim . Sébastien Le Prestre de Vauban immediately began to fortify the city by building the citadel of Strasbourg . With the subjugation of Alsace came the promotion of Catholicism in this area. This soon led to a change in denominational relationships. As part of the Reunion War of 1683/84, Louis XIV had Luxembourg occupied. This closed gaps in Vauban's fortification system. In Italy, too, the king was able to expand his position with the acquisition of Casale .

French politics met with outrage in the empire and contributed to the conclusion of a strictly defensive war constitution . She saw one of the imperial circles tory to standing army before that would be reinforced in case of war. Resistance to this came from the armed imperial estates such as Kurbrandenburg, who saw their position of power in danger. Emperor Leopold I was also not very satisfied with the result, because he would have preferred to have the Imperial Army under his own control. Instead, he relied on alliances with district associations, such as the Laxenburg Alliance . Despite all the deficits, the empire prepared for future military conflicts.

Due to the Ottoman offensive in 1683 with the climax of the second Turkish siege of Vienna , Leopold I was forced to take care of securing his hereditary lands. After overcoming the acute crisis, he continued to focus on the fight against the Ottomans. The Great Turkish War lasted until 1699, led to Austria becoming a great power, and greatly enhanced the emperor's prestige in the empire. This shift in priorities led Leopold I to conclude an armistice with France in the Regensburg standstill of 1684 and to temporarily recognize the reunions. The Regensburg standstill in no way meant that Louis XIV had given up his expansionist policy.

In addition to the expansive policy in the west of the empire, the repeal of the Edict of Nantes by the Edict of Fontainebleau in 1685 and the persecution of the Huguenots outraged Protestant Germany and the other Protestant powers. As a result, Louis XIV also lost one of his most important allies in the empire, the Elector of Brandenburg.

Palatine question

Louis XIV tried to use the emperor's bondage in the Turkish war to secure and expand the French territories gained through the reunification policy on Reichsboden. On the one hand, the dispute over the succession in the Archdiocese of Cologne and on the other hand the question of succession in the Palatinate came in handy as a pretext. Another factor was the establishment of the Augsburg Alliance.

Elector Karl I. Ludwig , the son of Frederick V , the Winter King, originally intended to stabilize political relations with neighboring France by marrying his daughter Liselotte of the Palatinate with Duke Philip of Orléans , brother of the "Sun King". The project went back to the mediation of Anna Gonzagas (1616–1684), the elector's sister-in-law, and her connections to the French court. Louis XIV intended to enter into a close political connection with the Electoral Palatinate in order to maintain his influence in the empire. The fact that the elector's son was considerably inferior to his sister in terms of vitality and that she therefore calculated certain chances of an inheritance may have played a role. The marriage contract provided for the Palatinate bride to renounce her territorial claims in the empire. But the allodial possessions were excluded from it. After the elector's death in 1680, his childless son Charles II died in 1685. The reformed line of the family died out. The rule passed with Philipp Wilhelm to the Catholic Pfalz-Neuburg . The new elector made no secret of his anti-French attitude.

The reason for French politics was the claim to the inheritance of Liselotte von der Pfalz, which was not adequately described in the marriage contract. Elector Karl Ludwig had recognized dispositions in money and kind in his will, while the elector had again rejected all claims in his will and disinherited Liselotte, but Louis XIV had this will annulled by the Paris Parliament .

Augsburg Alliance

In May 1686, Louis XIV had already threatened to enforce his brother's claims by force if necessary, and emphasized this with concentration of troops and the crossing of the Rhine. Against this background, the Augsburg Alliance was formed as a defensive alliance in the form of an expanded district association . It included the front imperial circles, the emperor, Spain for the Burgundian imperial circle and Sweden for its possessions located in the empire. The Kurpfalz, Kurbayern and Schleswig-Holstein-Gottorf also belonged to the alliance. The aim was to preserve the status quo on the basis of the Peace of Westphalia, the Peace of Nijmegen and the Regensburg standstill of 1684. The alliance was not really effective. Most of the parties involved had not even ratified the alliance. When Louis XIV began the War of the Palatinate Succession, he named among other things the alleged danger posed by the alliance as a reason for war. To him, the threat seemed to increase when Wilhelm III. von Orange and Friedrich Wilhelm von Brandenburg met in Kleve .

Cologne diocese dispute

The pro-French elector of Cologne Maximilian Heinrich von Bayern died in June 1688. His confidante Wilhelm Egon von Fürstenberg-Heiligenberg had previously secured the dignity of a coadjutor and thus the prospect of a successor with French money . Because the Pope refused to approve this appointment, an election of bishops was necessary. Joseph Clemens von Bayern competed against von Fürstenberg . Von Fürstenberg received the most votes, but missed the necessary two-thirds majority. Nonetheless, he considered himself a legitimate bishop and created facts by having the royal seat of Bonn and important places under military rule. The Electoral College and the Emperor turned to the Pope, who appointed Joseph Clemens Archbishop. Louis XIV did not accept the papal decision and sent von Fürstenberg a French army to help.

Alliance diplomacy

Relations between the Netherlands and France deteriorated sharply from late 1687, when Louis XIV took a more aggressive course. This led to a trade and customs war, which made a military conflict appear possible. Against this background, Wilhelm III began. of Orange in April 1688 to plan an alliance with Leopold I. The aim was the renewal of an imperial-Dutch assistance and defense agreement. However, with a view to the departure of the Netherlands in the Dutch War, Leopold I had considerable distrust of Wilhelm III.

In the course of these negotiations between the Netherlands and the emperor, there was also talk of imperial-French diplomatic contacts. According to this, Louis XIV is said to have promised not to intervene in the Palatinate and to return the entire Alsace if Leopold I should remain neutral in the event of a French war against the Netherlands. Louis XIV also does not want to interfere in the question of succession in Spain, where inheritance disputes threatened after the death of the feeble Charles II expected in the near future . Although the emperor himself reported about this in talks with the Dutch ambassador, these offers did not actually exist in this form. In the case of Alsace, for example, they would have contradicted a policy pursued by Louis XIV for years. There is no evidence of this in the French sources. Only at the lower diplomatic level were there secret contacts between Vienna and Versailles in order to seek a compromise. But there was no mention of any far-reaching concessions by France. In order for an alliance of the Catholic powers to come about, Louis XIV was prepared to give up his interests in the Palatinate, but that required the recognition of the reunions and the conversion of the Regensburg standstill into a peace agreement.

The alleged offer of an alliance by Louis XIV to the emperor served Vienna as a means of making its own goals clear to the Netherlands. This was on the one hand a revision of the western borders of the empire and on the other hand the clarification of the Spanish inheritance question. These points were basically Leopold I's conditions for an alliance with Wilhelm III. The latter also needed this alliance to diplomatically secure his goal of ascending the English throne. Official imperial-Dutch alliance negotiations took place after the start of the war, when the imperial positions became an issue again. In fact, the alliance treaty of May 1689 provided for the Dutch support of the Habsburgs on the question of Spanish succession.

For Louis XIV, too, the Spanish succession played an important role in his political planning. In 1688 he not only issued precise military instructions for the military occupation of the Spanish possessions in the name of the Dauphin, but also tried in this context to get the Bavarian elector on his side by offering him the kingdom of Naples and later helping Wittelsbach to the imperial crown to pull.

War manifestos

The French Minister of War François Michel Le Tellier de Louvois advised Louis XIV to act before the opposing alliance was ready and as long as the Turkish war distracted the opponents. On September 24, 1688, Louis XIV issued a war manifesto. In it he referred to his generous behavior when the Regensburg standstill came about and accused the emperor and the imperial princes of hostile behavior. He cited the Reich's refusal to convert the ceasefire into a peace treaty. He also accused him of not wanting to settle the Palatinate question amicably. Other points were the Cologne question and the establishment of the Augsburg Alliance. He offered to waive the claims in the Palatinate against a corresponding financial compensation. But he demanded that his candidate become Archbishop of Cologne, while he offered that Joseph Clemens could become coadjutor. He demanded once again that the armistice be converted into a peace treaty and that the empire would recognize the reunions.

He also tried to present himself as a defender of the rights of the Cologne cathedral chapter and the rights of the imperial estates against the emperor's claim to power. His real argument to justify a just war was that a war would forestall an attack by the Empire. So he was forced to take this step in order to protect France. This announcement was valid for three months. For the time after that, Louis XIV reserved all options for action. In the meantime, he announced that he would take possession of some fortresses and areas that should be returned after the war.

The emperor responded with his own manifesto. This is said to have been designed by Leibniz and was widespread through numerous editions. In it Leopold I rejected all accusations made by Louis XIV. On the one hand, he emphasized that he did not recognize the reunions and, on the other hand, acknowledged the content of the Regensburg standstill. He rejected allegations of having broken this through the formation of the Augsburg Alliance or other measures. All in all, he emphasized his peaceful stance, but was also ready to defend himself. He also tried to counter the impression that he would not adopt an aggressive policy towards the imperial estates.

course

Devastation of the Palatinate and the neighboring regions

As announced, France tried to enforce its demands by invading the Palatinate and the area on the left bank of the Rhine in 1688. Louis XIV hoped for a short campaign in the style of the Reunion War of 1683/84 . He didn't have a long war in mind.

In connection with the dispute over the occupation of the Archbishopric of Cologne, French troops occupied Bonn, Neuss and Kaiserswerth at the invitation of Fürstenberg . In Kurtrier , Koblenz and the Ehrenbreitstein Fortress offered resistance. The imperial city of Cologne was not attacked because it was protected by the troops of the Brandenburg Elector.

The fact that the army, which crossed the Rhine near Strasbourg on September 24, 1688 , was only 40,000 men strong, speaks for the hope of a short campaign . It was under the command of the Dauphin Louis de Bourbon and Marshal Durfort . The first goal of the war was the fortress Philippsburg . Sébastien Le Prestre de Vauban took command of the siege . The fortress fell in October 1688. Two weeks later, the Mannheim fortress fell . A short time later, the French conquered the Frankenthal Fortress . Surprised by the outbreak of war, Mainz and Heidelberg surrendered in the further course of the first weeks of the war . French troops reached far beyond Ulm and Mergentheim to plunder the country and collect contributions . Heidelberg, Mannheim, Speyer , Worms and other places were devastated. In an attempt to destroy the imperial cathedrals in Speyer and Worms, the Worms Cathedral burned down completely and the Speyer Cathedral was so badly damaged that the western nave collapsed and the western building had to be partially removed. During the military operations in Germany there was not a single field battle. The aim of the French was rather to put the enemy under pressure through targeted destruction. The hope of forcing the other side to accept the conditions of Louis XIV was not fulfilled.

The Swabian Imperial Circle and the Rhenish electors had not yet started concrete war preparations. The imperial troops were initially essentially still in the Turkish war bound and could afford no effective help. The defense order based on the imperial circles proved to be completely overwhelmed. First aid came from the armed imperial estates . But it took a month before the electors of Brandenburg , Saxony, the Duke of Braunschweig-Lüneburg and the Landgrave of Hesse-Kassel met in Magdeburg ( Magdeburg concert ) to discuss a common approach. As armed imperial estates, the princes involved provided the troops, while the non-armed estates had to provide accommodation and finance. The troops of the armed imperial estates raised war contributions themselves in the areas cleared by the French, which increased the suffering of the population. The support of the armed classes later forced the emperor to make political concessions. The award of the electoral dignity to Ernst August von Hanover was related to the position of an army and the consent of the emperor to the elevation of the Brandenburg elector in Prussia was also related to his military support. They also benefited financially from the subsidies of the sea powers and assignments of the emperor.

Initially, the troops of the Magdeburg Concert were deployed on the Lower Rhine and Middle Rhine from October 1688 . The Bavarian Elector Maximilian II. Emanuel commanded his own and imperial troops in the area of Frankfurt am Main . The scope of the war began to widen when the Netherlands decided to participate in November. For the first time, on February 15, 1689, an imperial declaration of war was made , to which, of course, not all imperial estates felt bound.

The clear reaction of the empire, the support from the Netherlands and the gradual concentration of troops on the Rhine showed Louis XIV that he could not expect the war to last for a short time. He decided to withdraw his own troops from their advanced positions. Instead, strong defensive forces were concentrated in Philippsburg, Freiburg im Breisgau , Breisach and Kehl . There were also French garrisons in Mainz .

On the advice of his Minister of War Louvois, Louis XIV had the Palatinate and neighboring areas systematically devastated during his retreat. Villages, castles and fortresses and entire cities were destroyed in the Palatinate, Kurtrier and Württemberg . Ezéchiel de Mélac contributed significantly to this as a French general. As of January 1689, eleven villages of the Heidelberg Oberamt south of the Neckar were burned down as planned after the residents had been driven out. Before the resistance of the Electoral Saxon troops near Weinheim , the French withdrew and, with riots against the population, laid Handschuhsheim to rubble and ashes. In Heidelberg only the fortifications of the castle and city were blown up, the French city commandant Count Tessé contented himself with a few smaller fires in the city towards his superiors, which ultimately only destroyed 34 houses. Mannheim, on the other hand, was razed to the ground as a fortress city. The French troops then turned south and continued their work of destruction on the central Upper Rhine ( Mühlburg , Durlach , Ettlingen and Pforzheim ) and in the Kraichgau ( Bretten ).

This was followed by the systematic destruction of the area on the left bank of the Rhine north of a line Philippsburg - Neustadt - Kaiserslautern - Mont Royal , above all the Palatinate authorities of Oppenheim and Alzey , but also the imperial cities of Speyer and Worms with their Romanesque episcopal churches.

The aim was to create an area that no longer had any tools or fortifications and could no longer serve as an enemy deployment area. As a result, numerous castles and other fortifications in particular were destroyed. Most of the castles on the left bank of the Rhine in what is now Rhineland-Palatinate , which were completely or partially still in existence , were destroyed in this context. These included about Burg Klopp , Ehrenfels , Schoenburg , Stahleck Castle , the castle Stolzenfels , the Cochem Castle , the Castles of Dahn or the Hambach Castle .

The military effect of the scorched earth was bought at the cost of a tremendous slump in public opinion in the empire and abroad to the detriment of France and its work of destruction. This helped to strengthen the opposing coalition.

Glorious Revolution and Irish Rebellion

In England there was resistance to the rule of Jacob II. Wilhelm III for various reasons . was offered to take its place by a group of high-ranking figures. An important reason for Wilhelm to accept this offer was his opposition to Louis XIV and the goal of increasing his power base for the conflict with France. The diplomatic security of the company in advance was of great importance. William III. received the assurance of armed Protestant imperial estates that they would protect the Netherlands and the western part of the empire in his absence. This was a prerequisite for the approval of the States General and in particular the dominant Holland for an invasion of England. The ambassadors of Wilhelm III emphasized. again and again the threat to Protestantism in Europe if one did not decide to intervene in England. An allegedly impending Catholic alliance between Vienna and Versailles was also brought into play.

Because of their concentration on the German theater of war, the French deployed only a weak army against the Spanish Netherlands, which took the fortresses of Dinant and Huy on the Meuse . The concentration of the French in Germany made it possible for Wilhelm III. from Orange to England and to take power there together with his wife Maria II . The disempowered Jacob II fled to France to the court of Louis XIV.

In Scotland and especially in Ireland there were revolts of the Jacobites against the new king and for a restoration of the Stuart rule . While the unrest in Scotland could soon be ended, in Ireland it was on a larger scale. The leader of the rebellion was Richard Talbot, 1st Earl of Tyrconnell . James II himself landed in Ireland with a French fleet in March 1689. In the Irish War he was supported by Louis XIV with money and soldiers. The French king hoped for it, so Wilhelm III. to be able to keep away from the European theater of war. Large naval operations, which are described below, also served to support the uprising.

With French help, James II raised an army of around 30,000 men. However, the soldiers were little experienced and poorly cared for. The army besieged the Protestant city of Londonderry , but eventually had to break the siege. William III. landed in Ireland in 1690 with a force of 35,000 men under the command of Friedrich von Schomberg . He was a Huguenot and formerly a Marshal of France . Allied troops marched on Dublin . James II tried for his part to stop this contingent with 23,000 Irish and French in the Battle of the Boyne . William III. won and James II fled back to France.

In October of that year John Churchill, 1st Duke of Marlborough , conquered the cities of Cork and Kinsale for William III. Godert de Ginkell first took Ballymore and, after a siege, Athlone in the summer of 1691. The soldiers of James II under Charles Chalmont de Saint-Ruth attacked the Allies a short time later at the Battle of Aughrim and were defeated.

As a result, the Allies captured most of the Irish bases. Only Limerick held out and could only be taken after a long siege in October 1691. With that, Wilhelm III. also enforced in Ireland.

In 1692 the French planned to land in England itself in order to bring James II back to the throne. However, the French did not succeed in achieving naval supremacy in the naval battles of Barfleur and La Hougue in the English Channel. Thus the military attempts of Louis XIV to restore the Stuart rule failed. The Dutch and the English were now able to intervene on the continent with stronger forces.

Great alliance

In 1689 the alliance against Louis XIV grew in strength. Of considerable importance was that with Wilhelm III. There was a personality of Orange around whom a broad coalition was formed at the beginning of 1689. In addition to the Kaiser, this was joined by Kurbrandenburg, Kursachsen, Kurbayern and the Duchy of Hanover. Some of the front circles of the empire also joined the alliance after 1691 with their district association of the Heilbronn Alliance . The war aims on the part of the German allies went so far as to want to push France back to the borders of 1648. The emperor concluded an offensive and defensive alliance with England in May / December 1689. Spain joined this in June 1690 and, furthermore, Savoy. The aim of the alliance was to take back from France all the territories it had annexed since 1659, to restore the Duchy of Lorraine and to give Pignerol to Savoy. In the event of the death of the Spanish King Charles II , his property should pass to the Austrian line of the House of Habsburg. An alliance between the Catholic Emperor and the Protestant powers was by no means a matter of course in the confessional age. So Leopold I first sought advice from his court theologian. More importantly, the Pope did not object. An alliance was thus formed that was to last until the end of the War of the Spanish Succession .

With the internationalization of the war, the war aims also increased. On the one hand, there was the French attempt to restore Stuart rule in England. It was also about the negative competition from the Netherlands for French trade. In addition, the conflict spread to the colonies.

Theoretically, the allies could have mustered around 400,000 men, which the French, under exerting all their might, could only have put up to a maximum of 260,000 men. In fact, the forces, especially on the Allied side, were significantly lower. The imperial army was far from its target strength and the imperial troops were used to a large extent against the Ottomans. The Brandenburgers, Saxons and Bavaria brought up strong forces. The Dutch provided 60,000 and the English 50,000 men. Spain came to about 40,000 men with difficulty. The Swedes and Danes participated more or less symbolically with small contingents. Savoy raised 15,000 men. The allies were numerically superior, but the French troops were experienced and were under a single command. The French army at that time was the strongest in Europe with an excellent organization for the time.

Contrary to what Louis XIV had hoped for, the conflict could not be limited. With internationalization it became clear that the war would last longer. France was poorly prepared for such a thing. It was all the more remarkable that the country was able to hold its own against a great superiority. The French strategy was to operate defensively on the Rhine. William of Orange was to be kept busy fighting the Jacobites in England. Louis XIV also hoped for another Ottoman offensive. He was confident that he could take out Savoy and defeat the Spanish troops in the Netherlands. Ultimately, he hoped that the opposing coalition would break up. It was of great importance that the fortress system was closed after the acquisition of Strasbourg and Casale and that France itself was hardly threatened.

Land war in Europe

Further development on the German theater of war

At the beginning of the 1689 campaign, the Allies had assembled an army of 150,000 men in the Rhineland. On the Lower Rhine, the Brandenburgers went under Elector Friedrich III. on the offensive. On March 12, 1689, they defeated the French in the decisive battle near Uerdingen . On June 13, 1689 they took part in the battle near Neuss Rheinberg and on June 27, 1689 Kaiserswerth. Then they began the siege of Bonn with the troops of other allies . The imperial commander-in-chief Karl von Lorraine began the siege of Mainz with 60,000 men . After the fall of the city on September 10, Lorraine marched north in support of the siege of Bonn. The siege led to extensive destruction of the city. Bonn capitulated on October 12th. This ensured the supremacy of Allianz in the Rhineland. From then on, Kurköln was one of France's opponents under Joseph Clemens von Bayern.

After the imperial successes, Joseph's election as German king in January 1690 was successful. The French tried to keep their fortresses on the Rhine. They benefited from the fact that the imperial troops were still largely claimed by the Turkish war.

In 1690, Max Emanuel von Bayern took over the high command in place of the late Karl von Lothringen . Opposite him stood the Dauphin Louis de Bourbon, dauphin de Viennois , supported by Marshal Guy Aldonce de Durfort, duc de Lorges . The campaign concentrated on the Breisgau . On the German theater of war, the French attempt to take Mainz by surprise failed in 1691. Effective warfare also failed because of internal disputes. However, it was possible to prevent the French-friendly imperial estates from falling away. The allies also prevented Sweden from making a peace push. It was true that the French had succeeded in putting the French on the defensive, but the troops of the Reich and the Kaiser were too weak to undertake a counter-offensive.

In the fourth year of the war (1692) the fighting was resumed by the French under Marshal Lorges with an advance to the northern Upper Rhine. They took Pforzheim , Vaihingen and Calw , among others , and tried in vain to conquer the Rheinfels fortress . At that time, Germany was only a secondary theater of war for both sides.

The overall less than pleasant situation prompted the emperor to transfer supreme command in the west to the Baden margrave Ludwig Wilhelm von Baden ("Türkenlouis"). Marshal Lorges went on the offensive again. Heidelberg captured again by the French on May 22, 1693 after a brief siege; On the one hand, to be able to book a quick success, on the other hand, to leave the imperial troops under the margrave Ludwig Wilhelm von Baden in the dark about the tactical goals. Feeling their quick and long-awaited victory, the French and, above all, the Jacobite troops, heavily drunk and barely hindered by their own officers, attacked the Heidelberg population, carried out a massacre and set fires that ultimately left the whole city to rubble . The castle, which was only damaged in a few places in 1689, burned down completely. The anti-French journalism in the empire drew mainly from the reports from Heidelberg itself and called the French king "worse than the Turks". Although the extensive destruction of the city was not intended, the king had a Te Deum sung and issued a medal with the inscription "Heidelberga deleta".

The Margrave of Baden was able to prevent the French from advancing further , especially by entrenching the Eppinger lines . Despite a few victories, he could not prevent the French from advancing to Württemberg and devastating the country as much as the Palatinate at the start of the war. In addition, the country had to promise the payment of 100,000 thalers annually as a war contribution. Lorges did not succeed, however, in forcing the Margrave of Baden into a decisive battle; the French troops returned across the Rhine. In the following period these were outnumbered on the German theater of war, so that they were essentially limited to defensive warfare and the defense of their own borders.

In 1694 Ludwig von Baden invaded Alsace without any particular success. Two years later the French prevented the troops under Ludwig von Baden from besieging Philippsburg . In the last year of the war, 1697, they were able to win the Ebernburg on the Nahe. Imperial soldiers under the command of the Margrave of Baden recaptured the castle on September 27th. In the same year an alliance of the Swabian, Franconian and Rhenish imperial circles was concluded with the Frankfurt Association . It was agreed to raise an army of 40,000 men in peacetime and 60,000 men in war. This number was never reached because, among other things, the Reich circles on the Rhine, which were particularly affected by the consequences of the war, were promised significant reductions in their obligations. Because the peace negotiations began shortly afterwards, the army was no longer used. The alliance was integrated by the international Vienna Grand Alliance .

Dutch theater of war

The Spanish Netherlands became the main arena of the war. While Wilhelm III. was in England, Georg Friedrich von Waldeck-Eisenberg commanded the Allied troops on the mainland.

At first, the French troops under Marshal Louis de Crévant and the Allies stood inactive for some time. On August 26, 1689, the French attacked the fortified camp of Walcourt ; they were repulsed.

The allies under Waldeck suffered a heavy defeat in the Battle of Fleurus on July 1, 1690 against the French commanded by Marshal François-Henri de Montmorency-Luxembourg . Because Luxembourg had surrendered troops and the Dutch received reinforcements from the Germans, the battle was not decisive. Waldeck was able to retreat to Brussels with the remnants of his army and rebuild it with Spanish and German forces. The Prussian elector led Waldeck's troops into an army of 55,000 men in August 1690.

The French opened the campaign of 1691 with the siege of Mons . Louis XIV led the 46,000-strong troops against Mons himself; Vauban directed the actual siege. The besiegers were covered by the Marshal of Luxembourg . The French managed to take the city on April 8th.

William III. landed with an army in the Netherlands after the Irish rebellion was put down, but was too weak to bring relief to the still besieged Mons . After the fall of Mons, the French marched towards Brussels , the army of Wilhelm III. hold up. The French under Marshal Louis-François de Boufflers bombed Liège in May . At Leuze, French troops struck Waldeck again in September 1691, without this Allied defeat having any consequences for the outcome of the war.

War Minister Louvois had made enormous armaments efforts shortly before his death. France was therefore able to operate on the Dutch theater of war with a huge army of 130,000 men. Of these troops alone, 50,000 to 60,000 men besieged Namur in 1692 . The siege - at which Louis XIV was present - was led by Vauban. The city was captured after five weeks. The Marshal of Luxembourg covered the siege with 60,000 to 65,000 men. The garrison in Namur was 6,000 strong. William III. and Maximilian II. Emanuel von Bayern, who had been appointed governor-general of the Spanish Netherlands, commanded the Allied army, but it did not succeed in bringing relief to Namur. Namur capitulated at the beginning of June, the citadel held out a little longer.

After the fall of Namur, Louis XIV declined to call Wilhelm III. to force a decisive battle. He himself returned to Versailles , while Luxembourg took over the command. Because he had to surrender a considerable part of the troops, the French army only had 80,000 men in the Netherlands. On August 3, it was surprising at Steenkerke by Wilhelm III. attacked. The Allies lost. The French did not take advantage of the success again, but Luxembourg limited itself to a bombardment of Charleroi . An English army landed in Ostend and took Furnes .

The French opened the 1693 campaign back in January. They managed to take some cities. Louis XIV reinforced the main army again with new troops without a decisive field battle. As in previous years, troops were withdrawn during the campaign. Nevertheless, under Marshal of Luxembourg, the French outnumbered the Allies. They managed to take Huy too. The Allies under the Duke of Württemberg made an unsuccessful advance against the Scheldt . Marshal Luxemburg and his army threatened Liège . This forced Wilhelm III. to react. He had only about 50,000 men, while the French had 80,000 men. Luxembourg attacked William III. and hit him on July 29th near Neer winds . The losses of the Allies and the French were great: a total of 20,000 men were killed or wounded. It was one of the most costly battles of the 17th century. The Allies also lost almost all cannons and numerous flags . Then the French conquered Charleroi . They now controlled the area on the Sambre and the Meuse and thus threatened Maastricht and Brussels. Mons, Charleroi, Namur and Huy had Louis XIV expanded into defensive positions with strong forces.

There was no significant fighting in the Netherlands in 1694. The allies only managed to retake Huy on September 28th.

After Marshal Luxemburg's death in the winter of 1694/95 and in view of the high financial burdens caused by the war and the weariness of the war, Louis XIV made the first peace offers. These were from Wilhelm III. and rejected the emperor. Louis XIV appointed François de Neufville, duc de Villeroy as the new French commander and also ordered the transition to defensive warfare in Flanders. In 1695, fortified lines were built between the River Lynx at Courtrai and the Scheldt at Avelghem . In June, William III besieged. and Friedrich III. with their armies of Namur . Together the siege troops numbered 80,000 men. The French stationed in the city were 13,000 strong.

The French commander had taken some cities and had Brussels bombed in August in order to induce the Allies to break off the siege. But this did not happen. The Allies succeeded some time later in regaining Namur, which was considered a great success. On the other hand, the siege tied the Allied troops long before Namur. An invasion of France was no longer an option because of the impending winter.

In the Netherlands in 1696 both sides were largely inactive. The main reasons were financial problems on the English and Dutch side, which prevented offensive warfare. William III. finally began to respond to the French peace feelers. He had about 60,000 men available. There were also around 40,000 men from Elector Maximilian II. Emanuel of Bavaria . The French had around 125,000 armed men in the area. Neither party dared a risky move.

To emphasize their push for peace negotiations, the French took another offensive approach in the Netherlands. They had three armies with a total of 190,000 men. The Allies combined only had 100,000 men. The French besieged Ath in May . The fortress fell after three weeks. After that, the armies remained inactive and waited for the results of the peace negotiations.

Italy

In Italy, French troops under Marshal Nicolas de Catinat marched into Piedmont with around 12,000 men in June 1690 . The Spanish-Savoy troops under Viktor Amadeus II of Savoy were decisively defeated at Staffarda on August 18th . The French were then able to occupy Savoy, including Carmagnola . As a result, Catinat was able to take various other cities in the region from the French main base in Pinerolo . Nevertheless, due to communication problems and supply bottlenecks, the French were forced to withdraw from Piedmont at the end of 1690 and seek refuge in their winter quarters west of the Alps. The French were therefore outnumbered. Nevertheless, under Catinat, the French conquered Nice , Villafranca and subsequently other places in the county of Nice in March 1691 . Of all the former Savoyard cities west of the Alps, only Montmélian was still in the hands of the Duke of Savoy. After the capture of Avigliana on May 29th, Catinat entrusted a large division under Feuquières and Bulonde with the siege of Cuneo on the Stura di Demonte in southern Piedmont. Max Emanuel II of Bavaria temporarily strengthened the Savoy. In October the allies were significantly stronger than the French and retook Carmagnola. After news of the arrival of cavalry units under Prince Eugene of Savoy arrived, which should rush to the aid of the besieged, Bulonde broke off the siege of Cuneo. Louis XIV offered Savoy the return of the conquered cities if this would accept his offer of peace. Viktor Amadeus II refused. While the French had only about 16,000 men in Italy, the Allies had about 50,000 men there. The French had to limit themselves to defending their fortresses Susa and Pinerolo.

In the war year 1692 Viktor Amadeus II penetrated the Dauphiné with the help of Austrian troops . The Allies had to withdraw again because the French blocked the way to Grenoble. In Italy, Viktor Amadeus II besieged Casale in 1693 . The French were able to drive the Allies out. The Duke of Savoy then besieged Pinerolo in July. After the French received reinforcements, Viktor Amadeus II had to withdraw. The French forced the Allies into battle. They suffered a heavy defeat at Marsaglia on October 4th . In June 1695 the Allies again besieged Casale. The allies made up of German, Spanish and Italian troops captured the city on July 9th. Then the Duke threatened Pinerolo.

Louis XIV began earnestly to seek peace with Savoy. There, on August 29, 1696, peace was concluded in the Treaty of Turin between France and Savoy. The duke renounced his war aims Casale and Pinerolo. In return he got Nice, Villafranca, Susa and other cities back. Italy was neutralized. When the Allies resisted, French and Savoyard troops jointly forced the Imperial and Spanish troops to agree to the peace with the Treaty of Vigevano .

Spain

In the first years of the war, the clashes in the Spanish theater of war, which essentially comprised Catalonia , were fought with relatively small armies. Supported by uprisings, a small French army under Marshal Anne-Jules de Noailles succeeded in conquering Camprodon in 1689 . In the following years, the French had to limit themselves to defensive warfare because of their weak troops. Nevertheless, they managed to conquer La Seu d'Urgell in 1691 . In 1693 the French captured Rosas in a coordinated action of land and sea forces . Then they took up a defensive position again because some of the troops were transferred to the Italian theater of war. Louis XIV reinforced the troops for the 1694 campaign. The army was supported by the French fleet . Between the Spanish and French army did the Battle of Torroella ; the French won. Supported by the fleet, Palamós and Gerona were besieged and taken. The French marched towards Barcelona. The French fleet encountered a strong Allied fleet and returned to Toulon. Against this background, Noailles broke off the advance with the land troops in order to secure the previously made conquests. For the next two years, the Allied fleet protected Barcelona . Reinforced by Allied troops, the Spaniards tried in vain to recapture some places in 1695. In the summer of the year, the previous French commander was replaced by Louis II Joseph de Bourbon, duc de Vendôme , due to illness . The Allies forced the French to withdraw near Gerona. Supported by an Allied fleet, the Spaniards besieged Palamós in August. After the fleet had left the scene, the land army broke off the siege and withdrew. The French destroyed the fortifications of Palamós and Castelfollit in 1694 . In the battle of Sant Esteve d'en Bas in 1695, a French unit of Catalan militias , the Miquelets, was attacked in two skirmishes and almost wiped out. In 1696, Vendôme tried in vain to take Ostalic ( Hostalric ).

Before the campaign of 1697, French troops in the Spanish theater of war were increased to 32,000 men. These faced around 20,000 Spaniards. The French army was supported by the navy. The French managed to take the besieged Barcelona .

Sea and colonial war

Fleet operations

In addition to the land war, the sea and colonial war between England and Holland on the one hand and France on the other played an important role.

The landing of Wilhelm III. in England in the autumn of 1688 was an outstanding military and logistical achievement. 500 transport and warships were involved. The participating fleet was four times the size of the Spanish Armada of 1588. The fleet landed an invading army of 21,000 men, mainly Dutch soldiers.

In the course of the Glorious Revolution , the naval officers sympathizing with Jacob II were dismissed and the English fleet submitted to the orders of Wilhelm III. The English fleet numbered around 100 ships of the line . However, not all ships could be used because the fleet had been neglected at the time of Charles II . The Dutch had 50 ships of the line and 32 frigates. During the war, new buildings almost doubled this number. Thanks to the building work by Jean-Baptiste Colbert and his son Jean-Baptiste Colbert, marquis de Seignelay , the French had over 70 ships of the line. In the following years the navy was further strengthened. After 1692 the fleet was neglected under new responsibility.

The actual naval war began with the landing of James II, supported by France, in Ireland in March 1689. This was followed by a stronger fleet in May. When the reinforcements intended for Jakob landed, the sea meeting in front of Bantry Bay was undecided . A small English fleet operated in the Irish Sea, helping the coastal towns in Ireland to defend them against the Jacobites. The English fleet also covered the landing of English troops in Ireland. But they could not prevent the French fleet from landing strong support forces again. The main English and French fleets operated in the summer at the entrance to the English Channel without seeking contact with the enemy.

In the spring of 1690, the English and Dutch sent a fleet to Cádiz to intercept the French Mediterranean fleet from Toulon . This did not succeed and the Mediterranean fleet reached Brest unscathed , where it united with the ships stationed there. The Allies noticed the French breakthrough too late and only returned to England with a delay. The allies under Arthur Herbert, 1st Earl of Torrington , and Cornelis Evertsen therefore only had a small fleet of 57 ships of the line in their home waters when the united French fleet under Anne Hilarion de Costentin de Tourville appeared off the English coast. Herbert wanted to avoid a fight, but was ordered to seek battle. The Allies were defeated in the Sea Battle of Beachy Head on July 10th. The French ruled the sea in the months that followed and hindered the allies' trade. This maritime success did nothing to change the defeat of the Jacobite insurgents, who were defeated in the Battle of the Boyne River .

Tourville ran out in June 1691 with 70 ships of the line and the order to seek battle only against weaker opponents. An Allied fleet of a hundred ships of the line under Russel was operating against him. Tourville managed with a superior seamanship to let the enemy sail behind the French fleet for a month without a battle. In 1691, the Allies were unable to benefit from their superiority. Instead, French privateers could seriously damage their opponents' trade.

In 1692 the French tried a second time to bring James II back to the English throne. This time troops were supposed to cross over directly to England and a large transport fleet was available. However, the English and Dutch succeeded in the naval battles of Barfleur and La Hougue (May 28 to June 2) to weaken the French fleet, making it impossible to cross over to England.

A year later, Tourville achieved another naval victory for France in the sea battle near Lagos when he intercepted the annual convoy of English and Dutch merchant ships - which were escorted by warships - before their voyage into the Mediterranean.

From 1694 onwards, the French distributed their fleet to various sea towns and concentrated on coastal protection, while the pirate war of the privateers continued. The Allies went on the offensive and attacked places on the French coast in order to force the French to move troops there and thereby weaken their armies for land war. The English and Dutch also helped the Spanish allies on the Mediterranean coast. The Allied attempt to land at Brest failed.

In the Mediterranean, the French fleet has supported land operations since 1693. Allied fleets operated against it. However, these only achieved a notable strength in 1694/95 with 70 ships of the line under Russel. At least it was possible to block the French fleet in Toulon. This contributed to the fact that the advance of the French land army in Italy came to a standstill.

Pirate and colonial war

In addition to regular fleet companies, both sides relied on the pirate and privateer war. Especially when the French renounced larger naval ventures, the importance of the privateer war increased. Navy ships and crews were hired out to pirate companies. Some of the buccaneers sailed in squadrons. Jean Bart and others were particularly successful . The French privateers brought in about 4,000 Allied merchant ships from 1691 to 1697. The losses led to numerous bankruptcies and the stock values of the East India Company or the Hudson's Bay Company fell sharply. Although the other side was only able to capture around 2,000 French merchant ships, the negative consequences on the French side were clearer. The much more extensive trade of the sea powers did not come to a standstill despite the losses, while French trade was badly affected. In the last years of the war, the Allies increasingly used their warships to protect their own trade, to pursue pirate ships and to blockade the French ports. If the warships were previously disarmed in winter, they have since been kept under arms all year round in order to be able to react quickly to privateer actions.

The naval war had relatively little impact overseas. Although the opponents in the West Indies attacked each other, there were no permanent conquests. In North America , English and French colonists fought frontier battles. In King William's War , a European conflict spread directly to North America for the first time. The French plan to conquer New York did not materialize. Instead, some New England settlements were raided. On the other hand, in 1690 the English attempts to conquer Quebec failed. In 1693 the Dutch in India succeeded in taking Pondicherry from the French . In contrast, the French conquered the city of Cartagena in Colombia in 1697 . This success contributed to Spain becoming ready for peace.

The naval war was a minor theater of the war, but it helped weaken the French economy. The same applies to a lesser extent to the opposite side. The financial consequences contributed to the readiness for peace on both sides.

Peace of Rijswijk

Peace negotiations

The war put great strain on France . The national debt began to rise from the beginning of the war and in 1698 reached its highest level of 138 million livres . In the end, the country was exhausted and the state was practically insolvent . The situation was exacerbated by a severe famine that peaked in 1693/94. It was triggered by poor harvests and the associated rise in grain prices. During this time, the number of deaths doubled. Trade also experienced a severe slump. This made the economic crisis worse. In addition to the economic and financial crisis and the misery of the rural population, the nobility and bourgeoisie began to express critical voices. This contributed to the fact that Louis XIV. Began to strive for peace more intensely from 1696 and showed willingness to compromise during the later negotiations.

Negotiations to end the war had been going on since 1693 and Louis XIV made offers to the naval powers in particular. There were no results. Louis XIV tried to strengthen his position again within the empire. French diplomacy succeeded in taking the Bavarian Elector more and more against Leopold I. He also took advantage of the disputes among the electors about the new electoral dignity for Hanover . He won the Pope by weakening Gallicanism and Savoy was drawn to the French side by abandoning some fortresses.

The departure of Savoy also made the other powers, in particular Wilhelm III, more willing to conclude a peace agreement. Louis XIV reinforced this by deploying the troops that had become free in Italy in the Netherlands and Spain and increasing the pressure there on the Allies. William III. announced on September 2, 1696 that he would begin peace negotiations with France. According to the King of England to the Allies, Louis XIV offered that the negotiations would take place on the basis of the Peace of Munster and Nijmegen. The French king was even prepared to forego some of his acquisitions, including Strasbourg.

This offer did not go far enough for Leopold I. He demanded the restitution of Lorraine, the return of Strasbourg, the ten Alsatian former imperial cities and the reunified territories. In this respect, these maximum demands had little weight, since the main military burden of the war had rested on the naval powers . William III. itself had no territorial claims. It was enough for him if Louis XIV would stop his support for the Stuarts and recognize him as King of England. The Spaniards naturally wanted to get back the reunited territories in the Spanish Netherlands . However, their economic and political situation was hardly suitable to keep the war going for long. The governor Max Emanuel von Bayern , who was in office in the Spanish Netherlands, ran his own game and hindered the military operations of the Allies rather than supporting them. Louis XIV increased the pressure with the deployment of three armies. The siege of the little important fortress Ath led to the fact that Wilhelm III. insisted on peace negotiations. Ultimately, the emperor also had to agree to this.

Louis XIV had made his peace offer more precise in February 1697 and was ready to renounce all reunions and also to return Strasbourg , Luxembourg , Mons , Charleroi and Dinant . The discussions began in May 1697 with Swedish mediation at Huis ter Nieuwburg near Rijswijk . Even under pressure from public opinion in England and the Netherlands , Wilhelm III insisted. to swift negotiations. When Charles II of Spain , the last representative of the Spanish line of the House of Habsburg , fell ill, Vienna delayed the negotiations in order to clarify the Spanish succession immediately after the death of the Spanish king. However, the inheritance did not occur, but the delaying tactics by the imperial negotiator Dominik Andreas I. von Kaunitz led to Wilhelm III. turned away from Leopold I. Among other things, this meant that there was no longer talk of the return of Strasbourg, but of Freiburg im Breisgau.

Without informing the other allies, Wilhelm III. by Johann Wilhelm Bentinck, 1st Earl of Portland , secret negotiations with Louis-François de Boufflers on the French side and came very far towards this. Both sides were now against the emperor. William III. claimed against the Protestant imperial estates , against their better judgment , that the emperor was conducting secret negotiations with Louis XIV. He brought the Protestant estates on his side and they, too, were ready for a quick peace.

However, the emperor was supported by a deputation from the Reichstag . This raised similar demands as Leopold I and also demanded compensation for the French destruction at the beginning of the war. The positions of the individual imperial estates cannot be discussed here, but it was clear that they were not united behind the conduct of the imperial negotiations.

In the meantime, Louis XIV had promised that Wilhelm III. to be recognized as King of England. The fall of Barcelona then prompted the Spaniards to quickly conclude a peace. On the night of September 20th to 21st, the Netherlands, England, Spain and Brandenburg signed peace with France without involving the emperor and empire. Isolated and sometimes put under pressure by its own imperial estates, Kaunitz also had to agree to peace on October 30, 1697.

Elector Johann Wilhelm could not get through with his demands for compensation for war damage, especially for the destruction of Mannheim, Heidelberg and Frankenthal. The district association and the militarily strongly committed imperial estates played no role in the negotiations. The high hopes on the German side were largely disappointed.

Content of the contract

The Peace of Westphalia of 1648 and the Peace of Nijmegen of 1679 were confirmed. The imperial city of Strasbourg, which has been occupied by France since 1681, and the whole of Alsace became or remained French, as did Saarlouis . The citizens of Strasbourg who did not want to become French had the right to leave the city within a year. France had enforced the Upper Rhine as the border to the empire. The hope in the empire of being able to reverse the French acquisitions in Alsace turned out to be in vain.

But France had to evacuate the remaining areas that had been gained after the peace of Nijmegen. Freiburg im Breisgau, Breisach and the Breisgau as a whole came back to Austria. The Duchy of Lorraine , the Principality of Pfalz-Zweibrücken and the numerous smaller territories on the left bank of the Rhine have been restored. However, Lorraine had to allow French troops to march through to the French fortresses on application.

Outside of Alsace, the reunions were thus reversed. This was quite a success for Leopold I, who had pursued this goal since 1680. The direct causes of war were compared. The French claims to the Palatine inheritance were later financially compensated. Von Fürstenberg was reinstated in his rights in the empire, but had to renounce the bishop's seat in Cologne.

France agreed with England to return all mutual annexations. In addition, Wilhelm III. recognized as king. France also undertook to return the principality of Orange . The Netherlands and France renounced mutual claims and concluded a trade agreement. The Dutch gave Pondicherry back to France. The Spaniards received Barcelona and the reunions of Luxembourg, Chiny, Mons, Charleroi, Ath and Courtlay back. The French, however, kept part of Santo Domingo .

Kaiser, France, the Palatinate Elector Johann Wilhelm and the (Catholic) Electors conducted secret negotiations about the fact that in peace the Catholic denomination introduced during the French occupation should also be preserved in the areas to be returned. The Protestants, who had found out about the negotiations, insisted that the denominations of the normal year 1624 must be maintained. Thereupon Louis XIV exerted pressure, and the Protestant cause also took place through Wilhelm III. little support. Finally, the "Rijswijker Clause" was included in the treaty, which reflects the denominational status introduced by the French, i. H. the Catholicism, laid down in the returned areas on the right bank of the Rhine. The clause also showed the counter-Reformation course of the Palatinate Elector Johann Wilhelm. The dispute over the clause led to significant conflicts within the empire during and after the War of the Spanish Succession; it lasted until 1734.

Post-history

Effects

The weakening of the French fleet after the naval battle of La Hougue (1692) and the neglect of French naval construction during the war were seen, especially by older research, as an important factor in the rise of Great Britain for its later maritime supremacy.

It was also important for future disputes that Wilhelm III in particular. the concept of the balance of powers was emphasized. The French attempt to massively change the equilibrium both in Europe and in the colonies should be opposed by the other powers.

Both parties to the conflict were successful, but both had to forego certain goals. This was a new experience for Louis XIV. The negative effects of the war on the French national budget were also immense. The war made it clear that against the backdrop of a broad alliance, the temporarily existing French hegemony was coming to an end.

Although the emperor's war goal was to clarify the Spanish succession, this did not come about in the peace treaty. It was therefore clear that the states would face another conflict in the foreseeable future. In this respect, the peace was only of a temporary nature. As early as 1700, with the death of the Spanish king, the next great war, the War of the Spanish Succession , cast a spell over Europe.

reception

The actions of the French army in Germany (especially the planned destruction by General Mélac ) generated anti-French resentment. The war was also a propaganda fight. Pamphlets in the sense of imperial patriotism or imperial propaganda sharply denounced the French approach. Louis XIV was reviled as a scourge of God and as an ally of the Turkish hereditary enemy and was called that himself.

The German nationalism of the 19th and 20th centuries was able to build on this contemporary criticism and the memory of 1688 thus contributed to the consolidation of the idea of a “ Franco-German hereditary enmity ”. At the latest with Napoleon's policy , Mélac was back in the canon of anti-French propaganda. This attitude was also reflected in the historiography. In the nationally oriented research of the 19th and 20th centuries, the Palatinate War was referred to as the Third Predatory War of Louis XIV. This view also shaped Kurt von Raumer's standard work from 1930 and has had a strong influence on local historical research.

The great importance of war in earlier historiography and memory culture faded after the Second World War and the Franco-German friendship. Apart from the affected region, the memory of the Palatinate War of Succession and the other wars of the 17th century is today heavily overlaid by the Thirty Years' War .

Timetable

1684

- August 15: The Regensburg standstill , which was concluded for 20 years, ends the war of reunions .

1685

- Louis XIV revokes the Edict of Nantes .

1686

- July: Formation of the Augsburg Alliance as a defensive alliance against France

1688

- June 5th: The Archbishop and Elector of Cologne Maximilian Heinrich von Bayern dies in Bonn.

- August: Pope Innocent XI. recognizes Joseph Clemens of Bavaria as the new Archbishop of Cologne.

- September 6: Belgrade falls to imperial troops under Elector Maximilian II Emanuel of Bavaria.

- September 24: Louis XIV's war manifesto.

- September 24th: French troops occupy Cologne .

- September 29th: French troops occupy Kaiserslautern .

- October 19: French troops occupy Mainz .

- October 29th: French troops take Philippsburg .

- October 24, 1688: Heidelberg surrenders without a fight to Marshal Duras on the condition that it is not destroyed

- October / November: French troops besiege Koblenz , but the city cannot be captured.

- November 15: William of Orange lands at Brixham in Devon, England.

- End of December: James II of England fled to France after being deposed.

1689

- February: The Perpetual Reichstag ends the Reich War against France.

- March 22nd: James II lands in Ireland.

- April 21: Maria II. And Wilhelm III. are crowned Queen and King of England, Scotland and Ireland.

- April: Start of the Jacobite uprising in Scotland under Bonnie Dundee

- May 11th: French victory under Château-Renault in the maritime meeting off Bantry Bay , Ireland; Landing of French troops in support of Jacob II.

- May 12: Alliance between the United Netherlands and Emperor Leopold I ( Vienna Great Alliance )

- May 17th: England enters the war.

- May: French troops advance to Gerona in Catalonia .

- June: Devastation of the Palatinate by French troops

- August 13: Landing of the Wilhelmine Marshal Schomberg near Carrickfergus , Ulster

- August 19: The water castle Staffort is blown up by Mélacs' troops and the surrounding Hardt villages are devastated

- September 10th: French defeat near Mainz, the city is retaken by imperial troops

- October 10th: French defeat at the siege of Bonn

1690

- June: King Charles II of Spain and Duke Viktor Amadeus II of Savoy join the alliance against France.

- June 14: Wilhelm III. von Orange lands at Carrickfergus with over 30,000 reinforcements.

- July 1st: The Marshal of Luxembourg wins a victory at Fleurus .

- July 10: French victory at Cap Béveziers (Beachy Head)

- July 11th: Defeat of Jacob II in the Battle of the Boyne , he flees to France.

- August 18: Marshal de Catinat defeats the Duke of Savoy at the Battle of Staffarda .

1691

- March 25th: Marshal de Catinat seizes the city of Nice .

- April 8th: Louis XIV takes Mons .

- May - August: Tourville patrols the coasts of France.

- July 16: Death of the Marquis de Louvois

- July 22nd: Decisive defeat of the Jacobites at the Battle of Aughrim

- October 3rd: Limerick - the last Jacobite bastion in Ireland - surrenders, the Treaty of Limerick ends the war of the two kings .

1692

- May 29th - June 4th: In the naval battles of Barfleur and La Hougue , the English and Dutch defeat the French under the Comte de Tourville. The French fleet trapped at La Hogue suffers heavy losses. The Battle of La Hogue is the decisive naval battle of the war.

- June 30th: French capture of Namur

- August 3: Marshal de Luxembourg defeats Wilhelm III. in the battle of Steenkerke .

- September 17th: Marshal de Lorges beats Duke Karl von Württemberg near Pforzheim.

1693

- May 22nd: French troops take Heidelberg and destroy the city.

- June 9th: Marshal de Noailles takes Rosas in Catalonia.

- 26-29. June: Tourville defeats the English Admiral George Rooke in the sea battle near Lagos on the Portuguese coast.

- July 29th: Marshal de Luxembourg defeats Wilhelm III. in the battle of Neerzüge .

- October 4th: Marshal de Catinat beats the Duke of Savoy and Prince Eugene at Marsaglia .

- At the age of 55 and after 43 years in the war, Louis XIV refrains from personally waging the war.

1694

- May: Marshal de Noailles offensive in Catalonia,

- May 27 Noailles victory at the Battle of Torroella

- June 18: British troops attempt at Camaret near Brest to land to the lying there French fleet off, but by Marshal Vauban repulsed .

- End of June: Jean Bart recaptures a French convoy near Texel.

- August: Marshal de Luxembourg seals off the northern French border.

1695

- January 4th: Marshal de Luxembourg dies

- August: British shell Dunkerque

- August: Renewal of the Vienna Grand Alliance in The Hague

- 14.-15. August: Marshal de Villeroy bombs Brussels to distract the Allies from Namur - the city burns down.

- September: Wilhelm III. of Orange, Namur recaptured after a two-month siege .

1696

- June: Jean Bart hijacks Dutch merchant ships at Doggerbank .

- August 29th: Peace of Turin between France and Savoy, Savoy moves to camp in France.

- October 6th: In the Treaty of Vigevano between France and Savoy on the one hand and the Habsburg powers Spain and Austria on the other, Italy is declared a neutral area.

1697

- May 3rd: French troops take Cartagena (in New Granada / Colombia).

- May: negotiations on a ceasefire start in Rijswijk

- August 10: The Duke de Vendôme and Admiral d'Estrées take Barcelona after two months of siege .

- September 20: England, Spain and the United Netherlands sign peace treaties with France.

- October 30th: The Peace of Rijswijk between the Empire and France ends the war.

swell

- Käyserliches Commissions-Decret concerning the recent French invasion of the Reich and hostile procedures. Like The Käyserliche Answer to the French Manifesto or Declaration. [Print translated from Latin, 1688] Digitized

- Peace treaty, such as such (...) 1697 between (...) Wilhelm III. King of Great Britain and Louis XIV King of France and Navarre, has been closed [Ryßwick]. [Print, 1697] Digitized

literature

- Karl Otmar von Aretin : The Old Empire 1648–1806. Volume 2: Imperial tradition and Austrian great power politics. (1684-1745). Klett-Cotta, Stuttgart 1997, ISBN 3-608-91489-7 .

- Karl Otmar von Aretin: The problem of warfare in the Holy Roman Empire. In: Ernst Willi Hansen (Ed.): Political change, organized violence and national security. Contributions to the recent history of Germany and France. Festschrift for Klaus-Jürgen Müller (= contributions to military history. 50). Oldenbourg, Munich 1995, ISBN 3-486-56063-8 , pp. 1-9.

- John Childs : The Nine Years' War and the British Army, 1688-1697. The Operations in the Low Countries. Manchester University Press et al., Manchester et al. 1991, ISBN 0-7190-3461-2 .

- Heinz Duchhardt : Old Reich and European states. 1648–1806 (= Encyclopedia of German History . 4). Oldenbourg, Munich 1990, ISBN 3-486-55431-X .

- Heinz Duchhardt, Matthias Schnettger , Martin Vogt (eds.): The Peace of Rijswijk 1697 (= publications of the Institute for European History, Mainz. Supplement 47). von Zabern, Mainz 1998, ISBN 3-8053-2522-3 .

- The French invasion of southwest Germany in 1693. Causes - consequences - problems. Contributions from the Backnang Symposium on September 10 and 11, 1993 (= Historegio. 1). Hennecke, Remshalden-Buoch 1994, ISBN 3-927981-43-5 .

- Pierre Gaxotte : Louis XIV. France's rise in Europe , Bastei Lübbe, Bergisch Gladbach, 1978, Original: La France de Louis XIV , translated by Hanns Jobst (first Munich: Nymphenburger Verlag , 1951). ISBN 3-404008-78-2 , ISBN 978-3-40-400878-0

- John A. Lynn : The Wars of Louis XIV. 1667-1714. Longman, London et al. 1999, ISBN 0-582-05629-2 . at Google Books

- John A Lynn: The French Wars 1667-1714. The Sun King at was (= Essential Histories. 34). Osprey Publishing, Oxford 2002, ISBN 1-84176-361-6 .

- Heinz Musall and Arnold Scheuerbrand: Destruction of settlements and fortifications in the late 17th and early 18th centuries (1674-1714) in: HISTORICAL ATLAS OF BADEN-WÜRTTEMBERG

- Max Plassmann: War and Defension on the Upper Rhine. The front imperial circles and Margrave Ludwig Wilhelm von Baden (1693–1706) (= historical research. 66). Duncker & Humblot, Berlin 2000, ISBN 3-428-09972-9 (also: Mainz, University, dissertation, 1998).

- Hans Prutz : Louvois and the devastation of the Palatinate 1688–89. In: German journal for historical science . Vol. 4, 1890, pp. 239-274, ( digitized version ).

- Kurt von Raumer : The destruction of the Palatinate in 1689 in connection with the French policy on the Rhine. Oldenbourg, Munich et al. 1930, (Reprint unchanged in the text, expanded to include the plate part. Pfaehler, Bad Neustadt an der Saale 1982, ISBN 3-922923-16-X ). Google Books

- Kurt von Raumer: The destruction of the Palatinate from 1689 - source problem and research task with a special look at the destruction of Speyer in: Historische Zeitschrift , vol. 139, no. 3, 1929, pages 510-533. on-line

- Geoffrey Symcox: The Crisis of the French Sea Power, 1688-1697. From the Guerre d'Escadre to the Guerre de Course (= Archives Internationales d'Histoire des Idées. 73). M. Nijhoff, The Hague 1974, ISBN 90-247-1645-4 .

- Roland Vetter: "The whole city burned down". Heidelberg's second destruction in the Palatinate War of Succession in 1693. 3rd, completely revised and enlarged edition. Braun, Karlsruhe 2009, ISBN 978-3-7650-8517-8 . online google books

- William Young: International Politics and Warfare in the Age of Louis XIV and Peter the Great. A Guide to the Historical Literature. Universe, New York NY et al. 2004, ISBN 0-595-32992-6 . Google Books

Web links

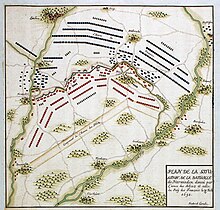

- Map of part of the Electoral Palatinate, the Electorate of Mainz and the Diocese of Worms with the camps and positions of the army of Louis XIV., 1696–1697 (DigAM digitales archiv marburg)

- War of the Palatinate Succession on landesgeschichte-online

Individual evidence

- ^ A b Heinz Duchhardt: The Reich and the European world of states 1648–1806 . Munich 1990, p. 22.

- ↑ cf .: Johannes Burckhardt: German history in the early modern times. Munich, 2009. P.80, Johannes Burckhardt: Completion and reorientation of the early modern empire 1648–1763 . Stuttgart, 2006; P. 103

- ^ Heinz Duchhardt: The Empire and the European States 1648-1806. Munich 1990, pp. 16-18.

- ^ Heinz Duchhardt: The Empire and the European States 1648-1806. Munich 1990, p. 19f.

- ^ Heinz Duchhardt: The Empire and the European States 1648-1806. Munich 1990, p. 21; Heinz Duchhardt: Baroque and Enlightenment. Munich 2007, p. 33.

- ^ Heinz Duchhardt: Baroque and Enlightenment . Munich 2007, p. 34; see: Karl Otmar von Aretin: The problem of warfare in the Holy Roman Empire. In: Ernst Willi Hansen (ed.): Political change, organized violence and national security: Contributions to the recent history of Germany and France. Munich 1995, pp. 1-9, here: pp. 3f.

- ^ Heinz Duchhardt: The Empire and the European States 1648-1806. Munich 1990, p. 21, Heinz Duchhardt: Baroque and Enlightenment. Munich 2007, p. 36.

- ^ Heinz Duchhardt: The Empire and the European States 1648-1806. Munich 1990, p. 21, Heinz Duchhardt: Baroque and Enlightenment. Munich 2007, p. 37.

- ^ War of the Palatinate Succession - Prehistory and Occasion

- ↑ Francis Smith: The Wars from Antiquity to the Present. Berlin u. a. 1911, p. 391.

- ^ Johannes Burkhardt: Completion and reorganization of the early modern empire 1648–1763. Stuttgart 2006, p. 129; Pierre Gaxotte: Louis XIV. France's rise in Europe. Bergisch Gladbach 1973, p. 265.

- ↑ Cf. for example Pierre Gaxotte: Louis XIV. France's rise in Europe. Bergisch Gladbach 1973, p. 266 .; Fritz Wagner : Europe in the age of absolutism and the enlightenment . In: Theodor Schieder / Fritz Wagner (ed.): Europe in the age of absolutism and the enlightenment . 3rd ed. Stuttgart, 1996 ( Handbuch der Europäische Geschichte Vol. 4) p. 29.

- ↑ on the bishop's election of 1688 forg .: Eduard Hegel: The Archdiocese of Cologne between Baroque and Enlightenment. From the Palatinate War to the end of the French period (1688–1811). Cologne, 1979 (History of the Archdiocese of Cologne, Vol. 4) pp. 35–42

- ↑ Christoph Kampmann : A great alliance of the Catholic dynasties 1688? New Perspectives on the Origin of the Nine Years' War and the Glorious Revolution. In: Historische Zeitschrift 294/2012, pp. 31–58, here: pp. 42–46.

- ↑ Christoph Kampmann: A great alliance of the Catholic dynasties 1688? New Perspectives on the Origin of the Nine Years' War and the Glorious Revolution. In: Historische Zeitschrift 294/2012, pp. 31–58, here: pp. 47–54.

- ^ Fritz Wagner: Europe in the age of absolutism and the enlightenment . In: Theodor Schieder / Fritz Wagner (ed.): Europe in the age of absolutism and the enlightenment . 3rd ed. Stuttgart, 1996 ( Handbuch der Europäische Geschichte Vol. 4) p. 29.

- ↑ Annuschka Tischer: Mars or Jupiter? Competing strategies of legitimation in the event of war. In: Christoph Kampmann u. a. (Ed.): Bourbon - Habsburg - Oranien: Competing Models in Dynastic Europe . Cologne u. a. 2008, pp. 196-211, here: p. 210; Pierre Gaxotte: Louis XIV. France's rise in Europe . Bergisch Gladbach 1973, p. 267.

- ↑ Karl Otmar von Aretin: The Old Empire 1648–1806 , Volume 2: Imperial tradition and Austrian great power politics (1684–1745). Stuttgart 1997, p. 29. Jutta Schumann: The other sun. Kaiserbild and media strategies in the age of Leopold I Berlin 2003, p. 191f.

- ^ A b c d William Young: International Politics and Warfare in the Age of Louis XIV and Peter the Great. Lincoln 2004, p. 222.

- ^ Fritz Wagner: Europe in the age of absolutism and the enlightenment . In: Theodor Schieder / Fritz Wagner (ed.): Europe in the age of absolutism and the enlightenment. 3rd ed. Stuttgart, 1996 (Handbuch der Europäische Geschichte Vol. 4) p. 29

- ↑ Francis Smith: The Wars from Antiquity to the Present. Berlin u. a. 1911, p. 391.

- ↑ Karl Otmar von Aretin: The Old Empire 1648–1806 , Volume 2: Imperial tradition and Austrian great power politics (1684–1745). Stuttgart 1997, p. 30; Karl Otmar von Aretin: The problem of warfare in the Holy Roman Empire. In: Ernst Willi Hansen (ed.): Political change, organized violence and national security: Contributions to the recent history of Germany and France. Munich 1995, p. 5f.