Karl I. Ludwig (Palatinate)

Karl I. Ludwig (born December 22, 1617 in Heidelberg ; † August 28, 1680 near Edingen ) from the Palatinate line of the Wittelsbach family (House Pfalz-Simmern ) was from 1649 until his death the Count Palatine of the Rhine , i.e. the Elector of the Palatinate . The most famous of his 16 children was Liselotte von der Pfalz .

Karl Ludwig's signature:

Life

Karl Ludwig was the oldest surviving son of the Palatinate Elector and Bohemian "Winter King" Friedrich V and Elisabeth Stuarts , a daughter of James I , King of England, Scotland and Ireland and sister of Karl I. He grew up with numerous siblings in his exile Parents in The Hague . After the death of his father in 1632, his uncle Ludwig Philipp became his guardian. In 1633 he was accepted as a knight in the Order of the Garter .

After the Peace of Westphalia , Karl Ludwig received the Electoral Palatinate back in 1649 in a reduced form, including the electoral dignity . This was made possible by the creation of an eighth cure of the Holy Roman Empire. The ore treasurer's office was connected to it after the ore clerk's office was transferred to Bavaria in 1623 (see ore office ). The Upper Palatinate , which had belonged to the Electoral Palatinate since the Pavia house contract , remained with Bavaria. But it was stipulated that if the Bavarian line were to expire, these lands and dignities should revert to the Palatinate (which happened in 1777 with the creation of Kurpfalz-Bayern ).

After the death of Emperor Ferdinand III. in 1657 Karl Ludwig celebrated his office as imperial vicar with vicariate coins in gold and silver. However, it was not yet clear who is entitled to exercise the vicariate. The Bavarian Elector had taken the old place of the Elector of the Palatinate. The Palatinate resigned from the eighth cure could refer to his rights evidenced by the Golden Bull. At the death of Emperor Ferdinand III. As a result, there was a dispute between Bavaria under Ferdinand Maria and the Palatinate over the imperial vicariate.

In the wars of the emperor and empire against France from 1673 to 1679, the latter wanted to force the elector to ally with him. Upon his refusal, a French army devastated the Electoral Palatinate in July 1674. After the Peace of Nijmegen, France forced the elector to pay a war tax of 150,000 guilders and, through the chambers of reunions, confiscated considerable areas of the Palatinate.

personality

Karl Ludwig's absolutist exercise of power in the state often had paternalistic features. He knew everyone, as it were, and took care of everything. After the Thirty Years' War, he worked hard to promote the reconstruction of the Electoral Palatinate as quickly as possible. The elector was constantly busy with government affairs, checked, allowed himself to be presented and often harshly intervened as soon as he suspected negligence and idleness. He publicly reprimanded clerks who, for example, appeared too late for an audience. This made him very popular with the common people.

The misfortunes in his family weighed heavily on him. At the funeral of his nine-year-old daughter Friederike, he wrote:

- “ Why do my dearest, innocent children not only have to die so early, but also with such pain, now for the second time? Am I not punished enough in so many other things? Do I take on myself so much and miss my office? When I am angry to the point of rage, am I mostly right to do so because of the malice, infidelity, disobedience and unrecognizability of people? Oh God, keep me from blasphemy and despair; O heart, endure without breaking, O mind, do not leave me until I breathe out for the last time with good courage and trust. "

As a staunch Calvinist , Karl Ludwig rendered an account of his God every day by examining his conscience . Nevertheless, as one of the few rulers at a time characterized by religious fanaticism, he saw a policy of religious tolerance as the best prerequisite for a prosperous coexistence of the population; So he had the so-called Konkordienkirche built in his Mannheim citadel Friedrichsburg from 1677 to 1680 as the new court church, which was to be open to all parishes in the city: the French Reformed, the German Reformed, the Dutch Reformed, the Lutheran and even the Catholic parish.

The Karl-Ludwig-See

Embedded in today's nature reserve "Hockenheimer Rheinbogen", south of Ketsch ( Rhein-Neckar-Kreis ), lies an extensive, formerly muddy depression, the area of which is still referred to as Karl-Ludwig-See. Elector Karl I. Ludwig was very popular with the people, because after the devastation of the Thirty Years' War he did a lot for the reconstruction of the Electoral Palatinate and for its economic development. In order to compensate for the sharp decline in the population, he sent advertisers to the neighboring states of Württemberg , Bavaria , Tyrol and Switzerland and lured them to the Electoral Palatinate with real estate and tax exemption . This action was successful, as has been handed down from relevant documents. In addition, he devoted himself intensively to the reorganization of the administration as well as the rebuilding of the school and finance system. As part of these measures, a huge pond and fish farm was built in 1649 in front of the village of Ketsch. The total area of the lake with 486 acres (= about 1.74 km 2 ) was remarkable for its time, and the income of fish and crustaceans ( crayfish Astacus astacus ) flourished, according to documentary entries. Even water turtles - possibly the native pond turtle ( Emys orbicularis ) - were caught there and brought to the Electoral Court in Heidelberg. There turtles were very popular as a delicacy. Also Liselotte of the Palatinate ( Madame Palatine ) mentioned this particular food that was served mostly on important occasions the Elector and his guests.

Numerous residents from the neighboring villages such as Alt-Losseheim (= spelling at the time for Altlußheim ), Schwetzingen , Ketsch, Hockenheim auf dem Sand, Oftersheim , St. Ilgen, Sandhausen and Walldorf were commissioned to build the structures of the Karl-Ludwig-See ( Dams, weirs, bridges), emptying the fish traps and every six years clearing the banks of the inflowing Kraichbach of useless vegetation. In the reign of Charles III. Philipp (1716–1742) began the decline of the lake. Due to several wars and strong Rhine floods, the complete disintegration of the facilities began in the middle of the 18th century. The former lake area was only used as grassland in the following period.

The Schwetzingen Castle

Even if the Schwetzingen Palace and in particular the palace gardens are usually mentioned in the same breath as the later Elector Karl Theodor (1724–1799), the importance and rise of this cultural site began under Karl I. Ludwig. Originally only laid out as a hunting lodge and used accordingly, it was severely destroyed in the Thirty Years War. The access to the bridge over the Leimbach was blown up and the residential building (today's central central building) burned down to the foundation walls. It was Karl I. Ludwig who decided in August 1656 to rebuild Schwetzingen Castle and to expand the complex accordingly. During a visit to the site in August 1656, he ordered the residents of Schwetzingen to clear away all rubble and debris, whereby the rubble, such as stones, wood and "old ironwork", could be left with the subjects for their own use. Motivated in this way, the residents of Schwetzingen and the neighboring communities had removed most of the rubble by next spring, so that the reconstruction of the court of honor and the central central / main building of the palace could already begin in 1657. A lack of funds initially delayed the project. Around 1665, the castle was finished to the point that it could be used again as an alternative and summer quarters. Old sources indicate that Karl I Ludwig already had an impressive collection of lemon and orange trees. After his death in 1681, this stock of plants was transported from the Friedrichsburg in Mannheim to Schwetzingen, where it was adequately housed in the newly built Pommeranzenhaus - then a common term for greenhouse or greenhouse. Orangery - to be housed. In 1689 the palace and garden were on fire again during the Palatinate-Orlean War.

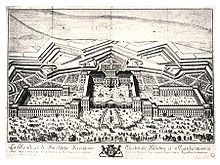

The Mannheim Castle

After the devastating devastation of his country and the destruction of his Heidelberg Castle by the Thirty Years' War , the Elector looked for a location to build a contemporary residence. In 1659 he sent a friendly message to the people of Worms and offered them “to do everything to help the city up and increase its trade, yes, he wanted to relocate the residence and university to the old Nibelungen seat and a citadel on the Rhine to protect the city , built at their own expense. ”This was rejected by the Worms loyal to the emperor, so that the second largest European residence was planned in Mannheim instead.

In 1664, Karl I. Ludwig commissioned Mannheim's first major building project after the Thirty Years' War. With the plans to build a new representative palace complex, for the development of which he commissioned the French architect Jean Marot, the importance of Mannheim grew suddenly. Although the building project was never carried out, the French architect's design set the trend for future European palace construction in the late 17th and 18th centuries. In recognition of his efforts for the Electoral Palatinate and the city of Mannheim , a statue was erected in the courtyard of the Mannheim Palace for Karl I Ludwig. In fact, the Mannheim Palace was built between 1720 and 1760.

The offspring

Karl I. Ludwig married Princess Charlotte of Hessen-Kassel (1627–1686), the daughter of Landgrave Wilhelm V of Hessen-Kassel and Amalie Elisabeth von Hanau-Münzenberg on February 22, 1650 in Kassel . The marriage had three children:

- Charles II, Elector Palatinate (1651–1685) ⚭ 1671 Princess Wilhelmine Ernestine of Denmark and Norway (1650–1706)

- Elisabeth Charlotte, Princess of the Palatinate (Liselotte of the Palatinate) (1652–1722) ⚭ 1671 Philippe of France, Duke of Orléans (1640–1701)

- Friedrich, Prince of the Palatinate (1653–1654)

As early as 1653, the marriage was apparently fundamentally broken. After the legally controversial divorce from his first wife on April 14, 1657 in Heidelberg, Karl Ludwig married Luise von Degenfeld on January 6, 1658 . With her he led a morganatic marriage, which was common at the time . This connection resulted in 13 children.

As early as 1667, Luise von Degenfeld had renounced all hereditary claims to the Palatinate in the name of her descendants and Karl Ludwig granted her and her children the title of Raugrafen and Raugräfinnen and they at the same time with the fiefs of the dignity that had been extinguished for centuries but has now been renewed Raugrafschaft equipped.

- Karl Ludwig Raugraf zu Pfalz (1658–1688), killed at Negroponte

- Karoline Elisabeth Raugräfin zu Pfalz (1659–1696) ⚭ 1683 Meinhard von Schomberg (1641–1719), 3rd Duke of Schomberg and 1st Duke of Leinster

- Luise Raugräfin zu Pfalz (1661–1733), letter partner of her half-sister Liselotte von der Pfalz

- Ludwig Raugraf of Pfalz (1662–1662)

- Amalie Elisabeth Raugräfin zu Pfalz (1663–1709), also a letter partner of Liselotte von der Pfalz

- Georg Ludwig Raugraf zu Pfalz (1664–1665)

- Frederike Raugräfin of Pfalz (1665–1674)

- Friedrich Wilhelm Raugraf of Palatinate (1666–1667)

- Karl Eduard Raugraf zu Pfalz (1668–1690)

- Sofie Raugräfin zu Pfalz (* / † 1669)

- Karl Moritz Raugraf zu Pfalz (1670–1702)

- Karl August Raugraf zu Pfalz (1672–1691)

- Karl Kasimir Raugraf zu Pfalz (1675–1691), died in a duel in Wolfenbüttel "of excessive drink"

After Luise von Degenfeld died in 1677 in her 14th childbed, Karl Ludwig tried in vain to obtain the consent of his first wife to an official divorce so that he could marry again on an equal footing and ensure the succession, since the marriage of his oldest and only legitimate son, of Prince Elector Karl, had been childless for seven years. When this failed because of Charlotte's strict refusal, in 1678 he tried to persuade his younger brother Ruprecht, who lived in England, to marry him as an equal in order to secure the line of succession from the Pfalz-Simmern line, but he also refused. A succession of the Catholic younger Neuburg line was in prospect.

In 1679 Karl Ludwig married again on the left hand side , namely the lady-in-waiting Elisabeth Holländer, daughter of Tobias Holländer , with whom he had a son.

- Karl Ludwig Holländer (born April 17, 1681 in Schaffhausen), later father-in-law of Heinrich-Damian Zurlauben (* 1690 in Zug; † 1734 in Reiden)

Karl Ludwig was an extremely thrifty family man, as can be seen from his biography: Growing up in difficult circumstances in Dutch exile, he returned to an Electoral Palatinate that had been devastated by the war. Nevertheless, he managed not only to bring the country back up again with great effort, but also to save a considerable fortune. His son squandered the money in a few years, and the country was devastated by the French due to the daughter's alleged inheritance claims: With all his efforts, Karl Ludwig had only "plowed the sea".

Because when his son and successor Karl II died on May 16, 1685 in Heidelberg with no heirs entitled to inherit, the French King Louis XIV raised for his brother, the Duke of Orleans, who was married to Liselotte, the sister of Charles II, Inheritance claims both to the entire private fortune of Charles II and to parts of the Electoral Palatinate. However, Emperor Leopold I and the Reichstag categorically rejected the demands of the French king. The result was that Louis XIV tried to enforce his claims by force of arms in the Palatinate War of Succession (1688–1697). The resistance from the Reich powers remained hesitant. In 1689 and a second time in 1693, Ludwig XIV had Heidelberg and neighboring areas of the Electoral Palatinate burned down by his army; the French general Ezéchiel de Mélac also had the Heidelberg castle set ablaze; it remained in ruins to this day.

ancestors

| Louis VI. Elector Palatinate (1539–1583) | |||||||||||||

| Friedrich IV. Elector of the Palatinate (1574–1610) | |||||||||||||

| Elisabeth of Hesse (1539–1582) | |||||||||||||

| Friedrich V Elector Palatinate (1596–1632) | |||||||||||||

| William I of Orange (1533–1584) | |||||||||||||

| Luise Juliana of Orange-Nassau (1576–1644) | |||||||||||||

| Charlotte de Bourbon-Montpensier (1547–1582) | |||||||||||||

| Karl I. Ludwig Elector Palatinate | |||||||||||||

| Mary Stuart Queen of France and Scotland (1542–1587) | |||||||||||||

| James I (VI.) King of England and Scotland (1566–1625) | |||||||||||||

| Henry Stuart, Lord Darnley (1545–1567) | |||||||||||||

| Elisabeth Stuart (1596–1662) | |||||||||||||

| Frederick II, King of Denmark and Norway (1534–1588) | |||||||||||||

| Anna of Denmark (1574-1619) | |||||||||||||

| Sophie of Mecklenburg (1557–1631) | |||||||||||||

literature

- K. Frey: The Karl-Ludwig-See. In: Badische Heimat. 59th Jg. (1979), No. 3, pp. 503-520.

- Peter Fuchs: Karl Ludwig. In: New German Biography (NDB). Volume 11, Duncker & Humblot, Berlin 1977, ISBN 3-428-00192-3 , pp. 246-249 ( digitized version ).

- Karl Hauck: Karl Ludwig, Elector Palatinate (1617–1680). Breitkopf & Härtel, Leipzig 1903

- Liselotte of the Palatinate : The letters of Liselotte . Munich 1979

- Karl Menzel : Karl I. Ludwig . In: Allgemeine Deutsche Biographie (ADB). Volume 15, Duncker & Humblot, Leipzig 1882, pp. 326-331.

- Wolfgang von Moers-Messmer: Heidelberg and its electors. The great time of Heidelberg's history as the capital and residence of the Electoral Palatinate . Verlag Regionalkultur, Weiher 2001, ISBN 3-89735-160-9

- Volker Press ; Wars and crises in Germany 1600–1715 . (= New German History; Vol. 5). Munich 1991, p. 424 ff.

- Volker Sellin : Elector Karl Ludwig of the Palatinate: attempt of a historical judgment. Society of Friends of Mannheim and the former Electoral Palatinate, Mannheim 1980

Web links

- Literature by and about Karl I. Ludwig in the catalog of the German National Library

- Works by and about Karl I. Ludwig in the German Digital Library

- Publications by and about Karl I. Ludwig in the VD 17 .

- Country studies online

- Niedermoor Karl-Ludwig-See

Individual evidence

- ^ Wolfgang von Moers-Messmer: Heidelberg and its electors. The great time of Heidelberg's history as the capital and residence of the Electoral Palatinate . Verlag Regionalkultur, Weiher 2001, ISBN 3-89735-160-9

- ↑ Friedrich Peter Wundt, Daniel Ludwig Wundt: Attempting a History of Life and the Government of Karl Ludwig Elector Palatinate, Geneva, in HL Legrand, 1786, pp. 143-145; Ludwig Häusser: History of the Rhenish Palatinate, Volume 2, 1856, pp. 644–645

- ↑ Annette v. Boetticher : Gravestones, epithaphs and memorial plaques of the Evangelical Lutheran. Neustädter Hof- und Stadtkirche St. Johannis in Hanover , brochure DIN A5 (20 pages, some with illustrations), publisher. from the church council of the ev.-luth. Neustädter Hof- und Stadtkirche St. Johannis, Hanover: 2002, p. 13

- ↑ Dirk Van der Cruysse: Being a Madame is a great craft. Liselotte of the Palatinate. A German princess at the court of the Sun King. From the French by Inge Leipold. 14th edition, Piper, Munich 2015, ISBN 3-492-22141-6 , p. 260.

| predecessor | Office | successor |

|---|---|---|

| Maximilian (I.) |

Elector Palatinate 1648–1680 |

Charles II |

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Karl I. Ludwig |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | Elector Palatinate |

| DATE OF BIRTH | December 22, 1617 |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | Heidelberg |

| DATE OF DEATH | August 28, 1680 |

| Place of death | at Edingen |