Battle of Camaret

| date | June 18, 1694 |

|---|---|

| place | near Brest , France |

| output | French victory |

| Parties to the conflict | |

|---|---|

| Commander | |

| Troop strength | |

| 10-12,000 man 36 battleships 12 bombards 80 transport ships |

several hundred men |

| losses | |

|

1 ship of the line |

45 wounded |

Palatinate War of Succession (1688–1697)

Philippsburg - Koblenz - Walcourt - Bantry Bay - Mainz - Bonn - Fleurus - Beachy Head - Boyne - Staffarda - Québec - Mons - Cuneo - Leuze - Aughrim - Barfleur / La Hougue - Namur 1 - Steenkerke - Lagos - Neerektiven - Marsaglia - Charleroi - Torroella - Camaret - Texel - Sant Esteve d'en Bas - Gerona - Dixmuyen - Namur 2 - Brussels - Ath - Cartagena - Barcelona

The Battle of Camaret was an amphibious landing in the Bay of Camaret on the south Atlantic coast of Brittany on June 18, 1694. As part of the Palatinate War of Succession , the British and Dutch tried to take the French port of Brest and destroy part of the French fleet stationed there. The attack was successfully repulsed by Marshal de Vauban in his only field command.

Overall context

At the beginning of 1694 Louis XIV decided to take the fighting to the Mediterranean and Spain . To help Marshal de Noailles take Barcelona and force Spain to sign a peace treaty, Admiral Tourville left Brest on April 24 with 71 ships of the line. Chateaurenault's squad followed him on May 7th.

After the English found out about this, they planned to take Brest together with the Dutch, as they did not consider this venture to be too difficult in the absence of Tourville and its fleet. For this they wanted to land an army of 7,000 to 8,000 men.

After Tourville's victory at Lagos in 1693, Willhelm III. sent a punitive expedition from England to Saint-Malo and planned similar retaliatory attacks against other French ports. After spies informed Louis XIV of the plans against Brest, he made Vauban in command of Brest and the four Breton dioceses from Concarneau to Saint-Brieuc .

Preparations

Under the command of British Admiral John Berkeley, 3rd Baron Berkeley of Stratton, a fleet was assembled in the port of Portsmouth , which consisted of 36 warships, 12 bombards and 40 transport ships, which were to carry the 10,000-strong invading army under Thomas Tollemache .

Vauban immediately began to organize the defense of the city and the rocky coast around it. Bad weather prevented the English fleet from sailing for a month, which gave the French just enough time to give the fleet a warm welcome.

General preparations

In 1685, three years before the outbreak of the War of the Palatinate Succession, Louis XIV had commissioned Vauban to inspect the coast from Dunkerque to Bayonne . During his first stay in Camaret, Vauban wrote in his memoirs on May 9, 1685:

“There are still two roads outside the Strait of Brest that serve as a corridor to its entrance, one of which (known as Berthaume) is prepared for all winds from the north and the other of Camaret against all winds from Le Midy, both of them can be kept well. Nothing further needs to be done with the von Berthaume, as it can be covered by cannons from land. There is, however, a small trading port near Camaret's with bays into which pirates retreat with impunity, which often happens in the course of wars or bad weather: it should therefore be necessary to build a battery of four or five cannons here should be supported by a tower and a walled enclosure to hold them back and to draw a net over the roadstead that would create a safe haven for merchant ships forced into the bay by bad weather or the risk of detention. "

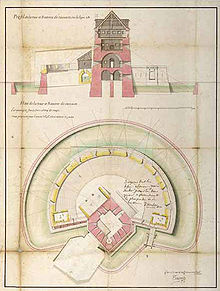

Shortly after the start of the war and after having already inspected the site, Vauban decided to first build a defensive position on Bertheaume and a tour de côte on Camaret, a unique example of its kind. Vauban's first designs included a round tower for the structure, however after visiting the site again, he decided on a polygonal tower. Shortly after the start of work on the Vauban Tower in 1689, the English, forewarned by their spies and realizing the importance of the work, attempted to destroy the tower. When sixteen Anglo-Dutch ships were sighted in the Bay of Camaret in 1691, five French frigates appeared to drive away the enemy's fleet. Given the task of defending hundreds of kilometers of coastline, the likelihood of having chosen the wrong place when selecting the defensive sites was very high, Vauban decided to build several fortresses at different locations should be maintained by militias, with the possibility of quickly pulling in regular troops from the hinterland at any time.

Concrete attack preparations

At the beginning of 1694, William III believed that Brest would be easy to take after hearing that Tourville had left the city with 53 ships of the line. So he decided to attack the port city. The historian Prosper Levot writes about the attack

"... seemed to be favored by the decision of Louis XIV to concentrate his naval forces in the Mediterranean in order to have Barcelona captured by Marshal de Noailles with their help in order to force Catalonia to implore Spain to conclude a peace agreement."

The plan of Wilhelm III. consisted in sending the bulk of the Anglo-Dutch fleet under the command of Edward Russell to Barcelona to fight Tourville, while the rest of the fleet under the command of John Berkeley invading forces under lieutenant-general Thomas Tollemache at the Breton Should withdraw from the coast near Brest in order to gain control of the Straits and the roads of Brest. Of prime importance was the consideration that the fate of Brest depended mainly on control of the strait. One remembered in particular a Spanish operation against Brest in 1594, in which Spanish troops of only 400 men held over 6,000 men under John IV of Aumont for more than a month in the siege of Crozon .

In view of the ever more concrete English threat, Louis XIV made Vauban "supreme commander of the entire French land and naval forces in the province of Brittany". Vauban had been lieutenant-général des Armées since 1688 and accepted the new position on one condition: that he would not become an "honorary (i.e. unpaid) lieutenant general in the Navy". The report of the fortifications of April 23, 1694 by engineers Traverse and Mollart only showed 265 and 17 in place. When Vauban reached the royal directives at the beginning of May, Brest was defended by around 1,300 men and 6 battalions, a cavalry regiment and a regiment of dragoons as reinforcements were on the way.

When Vauban arrived in Brest on May 23rd, he knew that the balance of power was working in his favor. He increased the number of reinforcements that were made at important points on the coast and reinforced the existing ones. In mid-June he inspected the defenses under his command and noted that large-scale troop landings were possible on the Baie de Douarnenez and Camaret. He ordered these to be strengthened. In an effort to prevent any landings and with no available warships, he equipped numerous sloops in such a way that they were suitable for the defense of the strait. The militias received weapons that had been requested by the navy. The cavalry regiments and dragoons were stationed in Landerneau and Quimper . In order to enable a quick exchange of information, Vauban organized a communication code in the form of signals. In a letter to Louis XIV dated June 17, 1694, he reported the following:

“Yesterday evening I found myself on the coast near Camaret and the area around the Bay of Douarnenez. I ordered the fortifications of various bays that could be raided to take in the Roscanvel Peninsula from behind, and all of our fortifications at Camaret. At the same time I designated the camps for the regiments from Roche-Courbon and Boëssière, which had still not arrived, the quarters for Monsieur de Cervon and Monsieur de la Vaisse, and the militia positions on land. The impetus for these measures had to be carried out urgently, without waiting for the troops to arrive, and five or six days of work could restore this part of the coast to good condition and ensure the defense. [...] "

battle

June 17, 1694

The Anglo-Dutch fleet (consisting of 36 ships of the line, 12 bombards, 80 transport ships and around 8,000 soldiers) under Berkeley finally set sail. Vauban received reports that the fleet was in the Iroise Sea on the evening of June 17th. She anchored halfway between Bertheaume and le Toulinguet near the Bay of Camaret close to the confluence with the port of Brest.

Rear Admiral Osborne, 2nd Duke of Leeds (accompanied by John Cutts ) approached the coast to scout the French positions and find possible landing sites. On his return he reported:

“(...) that the defensive positions, of which he could only see a small part, were formidable. But Berkeley and Talmash suspected that he was exaggerating the danger and decided to attack the next morning. "

At that time it was unknown to the English that the promised French support had still not arrived and that Vauban had written the following letter to the king on June 17th at 11 p.m.:

“(…) When we heard the Siganle from Ouessant at around 10:00 pm , which meant that a large fleet had been sighted. On the morning of the day the signals were confirmed and a messenger was sent to the commanders on Ouessant, we had learned that they had sighted 30 or 35 warships and over 80 other transport vehicles of all kinds, and it was between 4:00 p.m. and 5:00 p.m. : 00 o'clock confirms that they had anchored between Camaret and Bertheaume, still within range of the guns of the positions in these places, from where 8 or 10 projectiles were fired at them, but almost all of them failed. I have visited all the Cornouaille and Léon batteries, where I have sent various orders; one was able to count them and mark them quite well. There are three (ships with) cabins in front of the main masts and two (with such) in front of the foremasters, which leads me to believe that the armed force consists of English and Dutch. The wind is against them; if he turns, I have no doubt that tomorrow they will descend into the roadstead, maybe both. Our galleys did not come, which is a great misfortune for us. I had them ordered this evening to reach the harbor at any cost, to hold on to the coast to benefit from our rural artillery. I don't think they'll make it; but I know very well that I will do my best so that Your Majesty will be pleased with me, and I will no doubt not leave my place in this matter. Our affairs in the city are pretty well organized. "

June 18, 1694

On the morning of June 18, dense fog hindering both warring parties lay over this part of Brittany, which caused the English to postpone the attack. This suited the French insofar as "a cavalry corps, commanded by Monsieur de Cervon, and part of the militia (could) arrive at Châteaulin at 9:00 am". Therefore, after the fog had cleared, it was already 11:00 a.m. when Carmarthen was able to advance with eight ships to attack the Tour de Camaret and protect the 200 long boats with soldiers that were heading for the beach at Trez-Rouz. The Tour de Camaret, supported by the batteries of Le Gouin and Tremet, attacked the attackers so severely that two ships caught fire and the others were critically damaged. Despite their amazement at this unexpectedly strong resistance, the British managed to score a few hits on the tower. During this dispute, the steeple of the Notre-Dame de Rocamadour chapel was shot down by a cannonball.

“Legend has it that the Blessed Virgin appeared on the battlefield and sent the malicious bullet back to the battleship that was responsible, whereupon the same sank. However, the legend does not report that the maiden accomplished this deed by using the arm of a cannon from Vauban and one of his cannons! "

Meanwhile, Tollemache ended up on the beach at Trez-Rouz at the head of 1,300 men, including French Huguenots . They were met by heavy fire, whereupon, after a brief moment of swaying, they were attacked by 100 irregular men and 1,200 coastguard militia.

Macauley writes in his History of England :

“It soon became apparent that the project seemed even more dangerous than it had appeared the day before. Gun batteries, which retreated after firing, opened such murderous fire on the ships that several decks soon had to be cleared. A great number of foot soldiers and horses were recognizable; and they appeared to be regular troops, identified by their uniforms. The young rear admiral quickly dispatched an officer to warn Talmash. But Talmash was so completely obsessed with the idea that the French were unprepared to repel an attack that he ignored all respect and couldn't even believe his own eyes. He believed it certain that the force he saw gathering on the coast was a better bunch of peasants, hastily rounded up from the surrounding area. Confident that these would-be soldiers would run away from the real British soldiers like rabbits, he ordered his men to row towards the beach. He was soon taught better. A terrible bombardment cut down his troops faster than they could ever go ashore. He himself had barely reached dry ground when he was hit on the thigh by a cannonball and had to be carried back to his boat. His men returned to the boats in dismay. Ships and boats hurried to get out of the bay as quickly as possible, but they did not succeed until four hundred sailors and seven hundred soldiers had fallen. For many days, the waves washed dismembered and smashed corpses onto the beach in Brittany. The battery from which Talmash was wounded is called the Death of the English to this day . "

Tollemache was brought back to his squadron by one of the few longboats that were still seaworthy. French counterattacks drove the enemy back into the sea and the landing forces had nothing to do against them. They could not even retreat as the ebb tide had left the longboats aground. Only ten of the boats managed to rejoin the rest of the English fleet.

The English losses were considerable:

“(...) On the English side, 800 Landund troops were dead or wounded, 400 men were killed on the ships of the line and 466 were captured, including 16 officers. According to reports from Monsieur de Langeron and Monsieur de Saint-Pierre, who were admitted on the same day, the French had only 45 wounded, including 3 officers and the engineer Traverse, who lost an arm. "

Since that day the landing beach, stained with blood, has been known as Trez Rouz (Red Beach). The Talmash's landing points nearest cliff, or the battery that fired the shot at it, is still known today as Maro ar saozon (Death of the English).

When the battle began, Vauban himself was in Fort du Mengant and only reached the battlefield after it was all over. In a letter dated June 18 to the Comte de Pontchartrain from Camaret, he wrote:

“My only contribution was in the orders and the preparations; the main event took place two miles from me. I was told that we had met the enemy well, that there was not a moment's hesitation. They came straight away, they attacked straight away, in exactly the spot I had always suspected; in a word, they thought it out very well, but not so well executed. "

Effects

Talmash died of his injuries upon his return to Plymouth, and England's public grief and indignation at the treason were loudly voiced. After this defeat, the Anglo-Dutch fleet was overtaken and sailed back the English Channel in retaliation to bomb various ports, including Dieppe and Le Havre . In a five-day bombardment (from July 26th to 31st, 1694) Le Havre was badly damaged. In September the same fleet attacked Dunkirk and Calais , but the fortresses there were able to repel the attacks, so that the cities suffered only minor damage. These attacks gave Vauban the opportunity and cause to fortify the coast around Brest even more. So he set up a gun emplacement at Portizc, another on the île Longue, a third at Plougastel , etc. ...

To celebrate the victory, Louis XIV had a medal with “Custos orae Armoricae” (Guardian of the coast of Aremorica ) and “Angl. et Batav. caesis et fugatis 1694 ”(the English and Dutch found and put to flight in 1694). By a decision of December 23, 1697, Brittany exempted the citizens of Camaret “completely from any payment of hearth tax, poll tax or other taxes that may arise in the other municipalities of the province of Brittany”.

The "Camaret Bay Letter"

In search of a scapegoat after this bloody defeat, the English often blamed Marlborough , who was at that time with William III. Disgraced for other reasons, treason. He was accused of having written a warning letter to the deposed Jacob II in May 1694. This letter became known as the Camaret Bay Letter and reads (translated) as follows:

“Only today did I find out about the news that I am now writing to you; they say that the mortar ships and the twelve regiments stationed in Portsmouth, along with two regiments of marines, all commanded by Talmash, are destined to set fire to the port of Brest and any warriors who may be found there , to destroy. This would be a great advantage for England. But no consideration can or could ever prevent me from informing you of anything that might be of use to you. therefore you may derive your benefit from this information, on the truth of which you can fully rely. However, for the sake of your own interests, I must swear you not to let anyone know of this except the Queen and the bearer of this letter. Russell will set sail with forty ships tomorrow without having paid the rest yet; but it is agreed that within ten days the rest of the fleet will follow; and at the same time the land forces. I tried to get this to be confirmed by Admiral Russell himself some time ago. But he always denied it to me, although I'm sure that he had known the shape of the project for more than six weeks. This leaves the worst to fear about this man's intentions. I will be very pleased to know that this letter has reached you safely. "

The letter only exists in a French translation and Winston Churchill claims in his biography of Marlborough (his ancestors) that the letter was a forgery intended to damage Marlborough's reputation and that Duke William III. never cheated. While it is almost certain that Marlborough sent a message over the channel in early May describing the impending attack on Brest, it is just as certain that the French already knew about the plans for the Brest expedition from other sources. David Chandler concludes: “The whole story is so obscure and opaque that it is still not possible to make a definitive decision. All in all, we should credit Marlborough with the uncertainty of the doubt. "

Commemoration

In the north transept of the parish church of Saint-Rémi, partially covered by the organ pipes, there is a large stained glass window by Jim Sévellec showing the battle.

See also

Web links

- The history of England from the accession of James II. Chapter XX by Thomas Babington Macaulay.

- French representation of the attack

Individual evidence

- ^ Ernest Lavisse: Louis XIV: histoire d'un grand règne, 1643-1715 . Robert Laffont, Paris 1908, ISBN 2-221-05502-0 , pp. 767 (French).

- ^ Ernest Lavisse: Louis XIV: histoire d'un grand règne, 1643-1715 . Robert Laffont, Paris 1908, ISBN 2-221-05502-0 , pp. 768 (French).

- ↑ a b c d e f g h i j k Prosper Levot: Histoire de la ville et du port de Brest . 2nd Edition. Brest 1865, p. 387 (French).

- ↑ The battle is also known as the Brest Expedition .

- ^ Bernard Pujo: Vauban . Ed .: Albin Michel. Paris 1991, ISBN 2-226-05250-X , pp. 374 (French).

- ^ Anne Blanchard: Vauban . Paris 2007, ISBN 2-213-63410-6 , pp. 331 (French).

- ↑ a b c d e Georges-Gustave Toudouze: Camaret et Vauban . Alpina, Paris 1965, p. 95 (French).

- ↑ a b c d e Georges-Gustave Toudouze: Camaret Grand'Garde du littoral de l'Armorique . Gründ, Res Universis, coll. "Monographies des villes et villages de France", Paris 1993, ISBN 2-7428-0241-X , p. 100 (French, first edition: 1954).

- ^ Bernard Pujo: Vauban . Ed .: Albin Michel. Paris 1991, ISBN 2-226-05250-X , pp. 192 (French).

- ↑ Prosper Levot: La ville et le port jusqu'en 1681 . Volume I: Histoire de la ville et du port de Brest . Brest 1864, p. 387 (French).

- ^ Régis de l'Estourbeillon: Revue de Bretagne, de Vendée & d'Anjou - La défense des côtes de Bretagne au XVIIIe siècle . Brest 1910, p. 334 (French).

- ^ Bernard Pujo: Vauban . Ed .: Albin Michel. Paris 1991, ISBN 2-226-05250-X , pp. 191 (French).

- ^ Anne Blanchard: Vauban . Paris 2007, ISBN 2-213-63410-6 , pp. 334 (French).

- ^ Bernard Pujo: Vauban . Ed .: Albin Michel. Paris 1991, ISBN 2-226-05250-X , pp. 193 (French).

-

↑ The most likely numbers are quoted here. Other authors give the following estimates:

- 41 ships of the line, 14 fires , 12 bombards, 80 transport ships (G.-G. Toduouze, Camaret, Grand'Garde du littoral de l'Armorique )

- 36 ships of the line, 12 bombards, 80 smaller carrier ships with 8,000 men (P. Levot, Histoire de la ville et du port de Brest )

- 36 ships of the line, 12 bombards (Rapin-Thoyras, Histoire d'Angleterre )

- 29 tall ships , 27 frigates, mortar ships, bombards and tenders ( The United Service Journal )

- 36 warships without bringing the mortar ships and the infernal machines to bear ( The Monthly Review )

- 36 ships of the line, 12 bombards and transport ships that carried 8,000 soldiers ( Revue maritime et coloniale )

- ^ A b Thomas Babington Macaulay, 1st Baron Macaulay: History of the Reign of William III . 4th edition. Perrotin, 1857, p. 522 (English).

- ↑ Pierre Lozachmeur: Camaret: Son histoire, ses monuments religieux . 1968, p. 9 & 10 .

- ↑ Guillaume Lécuillier: Les étoiles de Vauban: La route des fortifications en Bretagne Normandie . Edition du huitième jour, Paris 2006, ISBN 2-914119-66-6 , pp. 166 (French).

- ^ Anne Blanchard: Vauban . Paris 2007, ISBN 2-213-63410-6 , pp. 335 (French).

- ^ Bernard Pujo: Vauban . Ed .: Albin Michel. Paris 1991, ISBN 2-226-05250-X , pp. 195 (French).

- ↑ La bataille de Trez-Rouz, en Presqu'île de Crozon , accessed on February 15, 2016.

- ^ Thomas Babington Macaulay: The History of England . Vol. 4: From the Accession of James the Second. London 1864, p. 829 (English).

- ^ Winston Churchill: Marlborough: His life and times, Book One . University Of Chicago Press, London 1933, ISBN 0-226-10633-0 , pp. 1050 f . (English).

- ^ Winston Churchill: Marlborough: His life and times, Book One . University Of Chicago Press, London 1933, ISBN 0-226-10633-0 , pp. 1051 (English).

- ^ A b David G. Chandler: Marlborough as Military Commander . London 1973, p. 48 . (English)