Saltpeter War

| date | 1879 to 1884 |

|---|---|

| place | Pacific coast of South America |

| output | Chilean victory |

| Territorial changes | Chile annexes Tarapacá and Antofagasta , causing Bolivia to lose access to the sea |

| Peace treaty |

Treaty of Ancón 1883 between Chile and Peru Treaty of Valparaíso 1884 between Chile and Bolivia |

| Parties to the conflict | |

|---|---|

| Commander | |

|

|

|

| losses | |

|

18,213 killed |

2,825 killed |

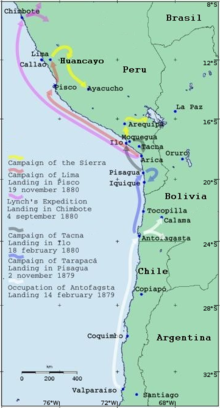

The Saltpeter War (also Pacific War , Spanish Guerra del Pacífico ) was waged between Chile on the one hand and Peru and Bolivia on the other around the regions of Región de Arica y Parinacota , Región de Tarapacá and Región de Atacama , in what is now northern Chile between 1879 and 1884.

In February 1878, the Bolivian government introduced a new export tax for Chilean saltpetre companies, thereby violating the border treaty of 1874, which expressly forbade the raising of existing taxes or the collection of new taxes on these Chilean companies for 25 years.

The government of Chile filed a complaint and offered to refer the matter to a neutral arbitration board . The Bolivian government considered the matter purely Bolivian and instead proposed that the dispute be resolved in Bolivian courts. The Chilean government stated that the collection of the new tax would mean the end of the border treaty and that Chile would no longer see itself bound by the border treaty and would renew its legal rights to the area. On February 6, 1879, Bolivia canceled the license of the Chilean company Compañía de Salitres y Ferrocarril de Antofagasta (CSFA) and confiscated their property. When an attempt was made to auction it on February 14, 1879, 200 Chilean soldiers landed in Antofagasta and took possession of the region, which is mostly Chilean.

Peru offered its mediation , but at the same time armed the army and navy and mobilized. Chile initially accepted Peru's mediation. Under Chilean pressure, Peru had to admit a bilateral connection with Bolivia via a secret treaty since 1873. Chile then demanded a declaration of neutrality from Peru at the end of March 1879, which Peru did not want to discuss until a parliamentary session that took place a month later. On April 5, Chile declared war on the Peru-Bolivia Alliance.

After six months of war, Chile was able to achieve maritime domination and thus isolated the coastal zones of the Atacama Desert, which were then only accessible by sea . In 1879 Chile occupied the Tarapaca region on the southern border of Bolivia with Chile and in mid-1880 the region around Tacna and Arica in the north of the disputed area. In 1880 Bolivia withdrew from the war. Lima, the capital of Peru, fell in January 1881. The war turned into guerrilla warfare and lasted until the end of 1883. A new government under Miguel Iglesias began negotiations with Chile and in 1884 signed the Treaty of Ancón . The Chilean troops then withdrew to the south.

The final borders with Bolivia were set in the 1904 Peace Treaty. Bolivia handed over Tarapaca and was given the right to use the port of Arica via a new railway line. Chile built the railway line between La Paz and Arica , which Bolivia was entitled to use free of charge. In the final peace treaties, the cities of Tacna to Peru and Arica to Chile.

prehistory

Controversial borders after independence

Alto Perú , as Bolivia was called during its colonial times, was initially part of the Viceroyalty of Peru . According to a decree of the Spanish Crown, it only had access to the sea via the then Peruvian Arica . In 1776 Spain transferred the territorial dependency of Alto Perú to the newly formed viceroyalty of La Plata , later Argentina . Thereby losing Alto Perú officially any right to access to the Pacific, as Spain divided the viceroyalties by oceans, that is, there was a viceroy of Peru on the Pacific and a Viceroyalty La Plata on the Atlantic.

After the end of Spanish colonial rule in South America between 1810 and 1830, the course of the borders between the new states was unclear in many regions, and conflicts ensued. The affiliation of the Ataca region on the Pacific coast between the newly formed states of Chile (founded in 1818), Peru (founded in 1821) and Bolivia (founded in 1825) was also controversial. The doctrine Uti possidetis provided for the adoption of the old borders of the Spanish colonies. Contrary to this doctrine, Bolivia claimed the largely unpopulated desert region as part of its national territory since the declaration of independence in 1825 and founded the port city of Cobija there in 1830 , which was tolerated by Chile. However, Chile continued to consider the region, which was 95% inhabited by Chileans, as its territory.

The 1866 border treaty between Bolivia and Chile

In the border treaty of 1866, Chile and Bolivia agreed on latitude 24 ° south as the north-south border and the " watershed line" as the east-west border. The zone between 23 ° and 25 ° south latitude became the "common profit zone" (Zona de beneficios mutuos) . The taxes from the extraction of minerals from this zone should be divided equally between Chile and Bolivia. This agreement turned out to be difficult to implement, as differences soon arose over the terms "minerals", the zone affiliation of the rich silver mines of Caracoles and the difficulties Bolivia had in transferring 50% of the tax collected to Chile.

In 1873 both governments tried to find a solution and the Corral Lindsay Protocol was negotiated to resolve the known discrepancies. This agreement was ratified by Chile, but the Bolivian parliament refused to approve it under pressure from Peru.

The secret alliance treaty between Peru and Bolivia of 1873 and the position of Argentina

In view of the growing influence of Chilean companies and further Chilean immigration to Bolivia and Antofagasta, Peru saw its supremacy in the South Pacific threatened and concluded a secret alliance with Bolivia with the aim of using military force to force Chile to revise the borders in favor of Peru and Bolivia.

The treaty also provided for the inclusion of Argentina in the alliance. In 1873 the Argentine House of Commons approved the project and granted 6,000,000 pesos of additional funding for the War Department. Due to territorial disputes with Bolivia over Tarija and Chaco, however, the three states were ultimately unable to agree on a joint approach, which is why the Argentine Senate failed to sign the agreement. Argentina refused a war effort for the militarily weak Bolivia, and Peru did not want to risk a war with Chile over Patagonia .

When tensions between Chile and Argentina increased in the years 1875 and 1878 because of the territorial disputes over Patagonia, Tierra del Fuego and the Strait of Magellan , Argentina tried to join the alliance, but this has since been rejected by Peru. At the beginning of the war in 1879, Peru and Bolivia offered Argentina the Chilean territories between 24 ° and 27 ° south latitude to join their alliance, but Argentina refused because of the weakness of its navy.

The 1874 border treaty between Bolivia and Chile

Bolivia changed its policy in 1874 and reached a new border treaty with Chile. The region north of the 24th southern parallel should continue to belong to Bolivia and the common economic zone should be dissolved on the condition that Bolivia was not allowed to increase the export tax for the Chilean companies now based in its territory for a period of 25 years.

The Peruvian saltpetre monopoly

Peru mined guano in the Tarapacá area and has financed large parts of its national budget with it since the 1840s. In the 1860s, however, government revenues declined due to the low quality and quantity of guano exports. At the same time, interest in the region grew when extensive deposits of nitrate ( saltpeter ) were found there during these years . This raw material was valuable and necessary for the manufacture of fertilizers and explosives . Because of the increasing trade in saltpetre on the world market, Peru had considerable difficulties in selling its guano from 1877 onwards; more than 650,000 tons were finally stored in the ports.

To compensate for the decreasing export of guano, the Peruvian government tried from 1873 to establish a state monopoly over the extraction and trade of saltpetre. In 1875 Peru nationalized all salitreras (saltpeter factories ), thereby ensuring that the state had direct control over production in its own country. But also further south, in Antofagasta before the Chilean border at that time, there were nitrate deposits. From 1876 the Peruvian state began to buy licenses for the extraction of saltpeter in Chile through the straw man Henry Meiggs .

The Compañía de Salitres y Ferrocarriles de Antofagasta

The Compañía de Salitres y Ferrocarriles de Antofagasta (CSFA for short) was a Chilean stock corporation based in Valparaíso . The CSFA had received a license from the Bolivian government under José Mariano Melgarejo to mine nitrates in Antofagasta. This first license was revoked after a coup and after negotiations between the CSFA and the new Bolivian government on December 27, 1873, it was again granted tax-free for 15 years. At the time, it was controversial whether this new licensing would require parliamentary approval. Thus the CSFA remained the only saltpetre producer that was not under the control of the Peruvian state.

The British company Antony Gibbs & Sons had a minority stake of 34% in CSFA and was at that time the only seller of Peruvian saltpetre in Europe. The government in Lima urged the Gibbs company to put pressure on the Chilean management of the CSFA to cut production. Henry Gibbs warned the CSFA that sticking to current production levels would create problems with Peru and Bolivia, which would see them as a violation of their interests.

The 10 centavos tax

| Miguel Iglesias , later President of Peru. His son Alejandro fell in the Battle of the Miraflores . | Juan José Latorre took part in the bombardment of El Callao, where his brother Elías Latorre was defending the fortress. |

In order to finance the state treasury, the Bolivian government under President Hilarión Daza decided in 1878 to impose a special tax of 10 centavos on every hundredweight of saltpeter extracted, thereby violating the treaty of 1874. Chile protested against this breach of contract. Bolivia initially waived the levying of the tax, but did not withdraw the law. Due to financial hardship after a year of drought and a lack of funds to repair earthquake damage, Bolivia decided in February 1878 to collect the tax from the profitable saltpetre industry CSFA retrospectively from 1874. After the CSFA refused to pay the tax with reference to the contract, Bolivia expropriated the CSFA-owned facilities in January 1879 and offered them for sale. Chile viewed this as an open breach and cancellation of the treaty of 1874 and sent troops to the city of Antofagasta, originally founded by Chileans (Juan López and José Santos Ossa) .

Conclusion: causes of the war

Ronald Bruce St. John says in The Bolivia-Chile-Peru Dispute in the Atacama Desert :

Even though the 1873 treaty and the imposition of the 10 centavos tax proved to be the casus belli, there were deeper, more fundamental reasons for the outbreak of hostilities in 1879. On the one hand, there was the power, prestige, and relative stability of Chile compared to the economic deterioration and political discontinuity which characterizes both Peru and Bolivia after independence. On the other, there was the ongoing competition for economical and political hegemony in the region, complicated by a deep antipathy between Peru and Chile. In this milieu, the vagueness of the boundaries between the three states, coupled with the discovery of valuable guano and nitrate deposits in the disputed territories, combined to produce a diplomatic conundrum of insurmountable proportions.

“The treaty of 1873 and the levying of the 10 centavos tax were the casus belli , but there were deeper and more important reasons for the outbreak of war in 1879. On the one hand, the power, prestige and relative stability of Chile in contrast to the economic decline and political instability in Peru and Bolivia after independence. On the other hand, it was about political and economic supremacy in the region. There was also a deep dislike between Peru and Chile. Under these conditions, the unclear borders between the three states together with the discovery of valuable guano and nitrate deposits in the disputed areas resulted in an insoluble conflict. "

The American historian William F. Sater names the following reasons for the war:

- The Chilean interests in the production facilities in the region and the plan to usurp them by occupying the area concerned to compensate for the reduced export income. Many shareholders in the CSFA were members of the Chilean government and put massive pressure on President Anibal Pinto and influenced public opinion to adopt a more confrontational policy towards Bolivia. Sater adds, however, that parts of the Chilean business elite had also made extensive investments in Bolivia and were therefore against an escalation of the conflict because they feared the possible loss of their property in Bolivia.

- The geopolitical interests of Peru and Chile in the South Pacific. Both Peru and Chile tried to get Bolivia on their side with the promise of a cheaper export port. Since the actual Bolivian export port was in Arica and not in Antofagasta, Peru ultimately offered more favorable conditions. At the same time, Chile offered Bolivia to occupy the Peruvian areas of Tacna and Arica and then to hand them over to Bolivia.

- The economic interests of Peru in a monopoly on saltpetre extraction to compensate for its reduced sales revenues from guano mining. As early as 1873 Peru tried in vain to bring the saltpetre trade under control by means of a state monopoly and in 1875 nationalized the saltpetre industry. In 1876 Peru began to acquire Bolivian licenses to mine nitrates and the government put pressure on the British company Antonny Gibbs & Sons to curb the CSFA's saltpetre production.

- The result of domestic and public pressure on the governments in both Chile and Peru to be intransigent in the dispute over the region. And the fear of the governments of both countries of being overthrown by a coup if they hesitate.

Start of war

Cast of Antofagasta

The Chilean units occupied the port city of Antofagasta on February 14, 1879, the day the company was to be auctioned off. Since only five percent of the population were Bolivians, there was no resistance. On February 22nd, 1879, Peru sent a group of diplomats, led by José Antonio de Lavalle, to Chile to mediate between Bolivia and Chile and find a peaceful solution. Meanwhile, Peru mobilized its armed forces. On February 27, the Bolivian parliament authorized the government to declare war, but this was initially not pronounced.

Declarations of war

On March 1, Bolivian President Hilarión Daza ordered various measures, including a ban on trade and communication with Chile “while the state of war persists” and the departure of all Chileans within ten days (except for cases of serious illness or disability ). Chilean mining companies were allowed to maintain their operations under the supervision of a state supervisor. The embargo measures should apply temporarily, unless hostile actions by the Chilean military require “a strong counter-attack from Bolivia”. Daza spoke of a "state of war", but a formal declaration of war had not yet been made. On March 4, the Peruvian legation under de Lavalle arrived in Valparaíso.

At an international meeting in Lima on March 14, Bolivia declared that it was at war with Chile. This was intended to make it more difficult for Chile to continue to procure weapons abroad. This undermined Peru's mediation efforts in Chile. On the same day, the Chilean Foreign Minister Alejandro Fierro sent a telegram to the Chilean ambassador in Lima, Joaquin Godoy, in order to obtain an immediate declaration of neutrality from Peru. On March 17, Godoy personally presented the Chilean concern to the Peruvian President Prado. The Peruvian government wanted to wait for the decision of the parliament.

Bolivia, in turn, asked Peru to recognize the case of alliance caused by Chile. When the Peruvian mediator de Lavalle in Chile was asked officially and directly whether Peru and Bolivia had a secret defense alliance and whether Peru intended to recognize the alliance case, he could no longer evade and answered both questions in the affirmative. Thereupon Chile declared war on Peru and Bolivia on April 5, 1879. On April 6, Peru declared an alliance case and declared war on Chile.

Naval warfare

The naval battles of Iquique and Punta Gruesa on May 21, 1879 brought the preliminary decision on Chilean naval rule . To prevent reinforcement of the Peruvian defenders of the port city of Iquique by sea, two older Chilean warships, the Esmeralda and the Covadonga , blocked the port. The two Peruvian armored ships Huáscar and Independencia met the Chilean blockade ships . The Peruvian coastal armored ship Huáscar rammed and sank the Chilean corvette Esmeralda . In pursuit of the Chilean gunboat Covadonga , the powerful Peruvian armored frigate Independencia ran aground near the coast. To prevent the ship from falling into the hands of the Chileans, its own crew set it on fire.

| Warship |

Tonnage ( tn.l. ) |

Power ( hp ) |

Speed ( kn ) |

Armor ( cm ) |

Main artillery |

construction year |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

3,560 | 2,000 | 9-12.8 | up to 23 | 6 x 22.8 cm | 1874 |

|

|

3,560 | 3,000 | 9-12.8 | up to 23 | 6 x 22.8 cm | 1874 |

|

|

1,130 | 1,200 | 10-11 | 11.4 | 2 x 25.4 cm | 1865 |

|

|

2,004 | 1,500 | 12-13 | 11.4 | 2 × 23 cm | 1865 |

|

|

1,034 | 320 | 6th | 25.4 | 2 × 38 cm | 1864 |

|

|

1,034 | 320 | 6th | 25.4 | 2 × 38 cm | 1864 |

For six months the Huáscar was able to escape the Chilean fleet and effectively disrupted the Chilean supplies. On July 23, 1879, the Chilean transporter Rímac was captured by the Huáscar and a cavalry regiment captured. In doing so, she avoided major confrontations with the superior Chilean fleet. But on October 8, 1879, the two modern Chilean armored ships Cochrane and Blanco Encalada, with the help of the Chilean ships O'Higgins and Loa, managed to bring the Huáscar off Punta Angamos and to conquer them in the naval battle of Angamos . The heavily damaged Huáscar was repaired by the Chileans and later used against Peru. With the elimination of the two sea-capable and powerful armored ships of Peru, Chile had finally achieved naval supremacy.

In August 1879, the Peruvian Union sailed along the entire Chilean coast to Punta Arenas to capture a merchant ship loaded with weapons for Chile. However, the merchant ship escaped.

The old coastal armored ships Manco Cápac and Atahualpa that remained in Peru were in poor condition and, due to their construction, were only suitable for the defense of coastal waters. The Manco Cápac was blown up in the bay of Arica by the Peruvians themselves when Chilean troops stormed the port city from the land side and the escape route across the sea was relocated by a Chilean squadron. The Atahualpa was later, after the failed defense of Lima , in the port of Callao sunk also by its own crew.

Although the Peruvian Navy no longer had any ships that could have withstood the Chilean armored ships for a long time, the Peruvians managed to sink two Chilean ships with cunning during the Callao blockade. The loa and covadonga were sunk by boats loaded with delicacies, fruit and drinks and carrying explosives under a false floor.

After the Peruvian fleet had been decisively weakened, Chilean troops could safely use the sea route. The isolated Peruvian garrisons in the south of the country were one after the other overwhelmed.

Land war

Tarapacá campaign

Two weeks after the Huáscar was captured , the Chilean army began to invade Peru . Unrestricted naval supremacy allowed the Chileans to land 10,000 men near Pisagua . Here the Peruvian-Bolivian army was split into two parts (in the north Lima, Arequipa and Tacna, in the south Iquique).

In order to occupy Tarapacá, then the southernmost province of Peru, the Chileans marched towards Iquique after landing in Pisagua . It was here that the first battle of this campaign took place, the Battle of San Francisco . The Chilean army was heavily attacked and both sides suffered losses. After the withdrawal of Bolivian units, the Peruvians had to retreat to Tarapacá . Iquique fell four days later.

In April 1879, the Bolivian dictator Hilarión Daza sent his troops to Arica to support Peru. The advance ended miserably, the troops almost died of thirst in the Atacama desert and had to turn back. This failure led to the removal of Dazas.

An expeditionary force with 3,600 soldiers and artillery was sent to intercept the remaining Peruvian troops. The Chileans encountered fewer than 2,000 Peruvian soldiers. These were poorly trained and demoralized by the previous defeat. The Chileans held a key position and surrounded the city before starting their attack. In the battle of Tarapacá , the Peruvians still managed to win. The Chileans had to leave behind a lot of ammunition and supplies. The victory had hardly any consequences, however, as the Chileans had already disembarked 12,000 men in Pacocha Bay near Pisagua. The Peruvians had to give up hopes of reinforcements for the provinces of Arica and Tacna .

Moquegua campaign

On June 7, 1880, 7,000 Chilean soldiers, supported by the navy, attacked the Peruvian garrison in the city of Arica. This was defended by Colonel Francisco Bolognesi with 2,000 men. The Chileans were led by Division General Manuel Jesús Baquedano González . The decisive factor was the battle plan drawn up by his chief of staff, Lieutenant Colonel Pedro Lagos , which envisaged the rapid capture of the Peruvian fortress on El Morro (German: "Great Hill") as a guarantee of victory. The Battle of Arica killed 474 Chilean soldiers and around 1,000 Peruvian soldiers. The Peruvian commander Francisco Bolognesi was among the dead. El Morro is now considered a national symbol in both Peru and Chile.

After the victory of Chilean troops over a Peruvian-Bolivian army at Tacna (Batalla del Alto de la Alianza) , Bolivia withdrew from the war and limited itself to securing the access to the Bolivian highlands, which allowed the Chilean troops to turn to Peru alone.

Lynch's expedition

To show the government of Peru the futility of further resistance, the Chilean government sent an expedition of 2,200 men under the command of Patricio Lynch to northern Peru with the aim of collecting taxes from the large landowners and the cities. On September 10, 1880, the expedition landed in Chimbote and raised 100,000 pesos in local currency, 10,000 pesos in paita, 20,000 pesos in Chiclayo and 4,000 pesos in Lambayeque. If you didn't pay, your property was destroyed. On September 11th, the Peruvian government issued a decree punishing the payments as treason, but most of the owners paid. This expedition, also criticized by Chileans, was covered by the then applicable laws of war. The Chilean historian Barros Arana calls Johann Caspar Bluntschlis' article 544 Le droit international codifié and Sergio Villalobos quotes Andres Bellos Principios del derecho Internacional .

Diplomatic efforts to find a solution

In October 1880, the United States tried unsuccessfully to mediate in the conflict on board the Lackawanna . The attempt to end the war with diplomacy failed at Arica Bay. Representatives from Chile, Peru and Bolivia met to discuss the territorial conflicts, however Peru and Bolivia rejected the loss of their territories to Chile and left the conference.

Lima campaign

After landing in Pisco on November 19, 1880, the Chilean army marched on the Peruvian capital Lima . On January 13, 1881, the Peruvians were defeated by the Chileans in the Battle of San Juan and Chorrillos . Two days later, the Peruvians were also defeated in the Battle of Miraflores . After the ceasefire in San Juan on January 15, negotiated through the mediation of the French and British ambassadors, the Peruvians had to cede Lima to the Chileans. On January 17, 1881, the troops of the Chilean general Manuel Baquedano entered Lima. The southern suburbs of Lima, including the coastline of Chorrillos , were captured and burned. A number of outlying haciendas were infected by Chinese workers; these had been recruited from China as slave substitutes. Above all, however, deserted Peruvian soldiers were involved in the pillage and pillage of Lima. A few days later, the port city of Callao also fell .

Huamachuco campaign

After the dissolution of the central government in Peru, the character of the war changed to a two-year guerrilla war in the Peruvian highlands. It was not until 1883 that the Chileans under Admiral Patricio Lynch were able to confront and beat the troops of the Peruvian general Andrés Avelino Cáceres in the interior of the country at the Battle of Huamachuco on July 10, 1883.

The persecution of Cáceres began in Lima on April 24, 1883. In mid-June, the Chilean troops under the command of Arriagada gave up the pursuit in the south, but Cáceres, ignorant of this fact, fled on to Pomabamba in Ancash , where he decided who to attack Chilean troops in the north separately and to smash the peace-ready Peruvian government of Miguel Iglesias in Cajamarca . But he only came to Huamachuco after the various Chilean troops had united in the north. The last able-bodied Peruvian army was defeated. Cáceres himself was only able to hide injured after the battle. He later became president of the country years after the Chileans withdrew from Peru.

The Peruvian army under Admiral Lizardo Montero Flores in southern Peru gave up the fight.

The new Peruvian leadership under Miguel Iglesias began peace negotiations and accepted the terms of surrender, which provided for the provisional cession of the Tarapaca and Tacna regions to Chile.

End of war

On October 20, 1883, Chile and Peru signed the Treaty of Ancón . In it, Chile received the Peruvian province of Tarapacá and expanded its territory to Tacna , which was returned to Peru almost 50 years later.

On April 4, 1884, the Treaty of Valparaíso came about between Chile and Bolivia . In it, Chile received the coastal region around Antofagasta, which in addition to losing a province, also cost Bolivia access to the Pacific. Bolivia became a landlocked country again . Port cities such as Antofagasta , Iquique and Arica were finally incorporated into Chilean territory.

It was not until 1904 that the peace treaty between Chile and Bolivia , which is still valid today , was signed, in which Bolivia confirmed that the Ataca region was part of Chile. In return, Chile granted Bolivia duty-free access to the ports of Arica and Antofagasta and the construction of a railway that would connect the capital La Paz with the coastal city of Arica.

The cities of Arica and Tacna remained occupied by Chile for a long time. It was not until 1929 that Arica Chile was struck; Tacna stayed with Peru.

Foreign intervention

Gun purchases

British historian B. Farcau claims:

“Contrary to popular belief that the 'dealers of death' would drag out the conflict in order to earn more, the nitrate dealers and the holders of the increasing promissory notes of the Belligerants were influential businessmen and their respective consuls and ambassadors they were all convinced that the only way they could get their bonds and profits back was to end the war and start trading again without disrupting legal follow-up disputes over ownership of the region's resources. "

Nonetheless, those involved in the war were able to buy torpedo boats, weapons and ammunition abroad and circumvent unclear laws of neutrality. Firms like the Baring Brothers in London had no problem working for both sides. Guns were of course only sold to those who could pay for them. For example, in the period from 1879 to 1880, Peru purchased weapons from the United States, Europe, Costa Rica, and Panama. They were unloaded on the Caribbean side of Panama and transported by rail to the Pacific coast. There they were brought to Peru by ship ( Talisman , Chalaco , Limeña , Estrella and Guadiana ). This action took place with the approval of the government of Panama (at that time still part of Colombia). The Chilean consul protested against these transports several times because the Chile-Colombia Treaty of 1844 forbade any supply of weapons to the enemies of the signatories.

USA politics

The US diplomats were concerned that the European powers might be inclined to intervene in the Pacific. After the occupation of Tarapaca and Antofagasta, the governments of Peru and Bolivia, as a last hope, asked the US to prevent the annexation of these territories by Chile. The ambassador of Bolivia in Washington offered the US Secretary of State William Maxwell Evarts the prospect of lucrative guano and nitrate licenses for US investors in return for the official US protection of the Bolivian territorial integrity. Isaac P. Christiancy , US Ambassador to Peru, organized the failed (USS) Lackawamma peace conference. Christiancy had previously proposed in the USA to annex Peru and take it into the Union after 10 years in order to give the USA access to these rich markets.

In 1881 James Garfield took over the presidency and his Anglophobic Secretary of State James G. Blaine was in favor of a more committed US policy in the Saltpeter War, particularly with regard to US investment in guano and nitrate licenses. Blaine argued that the republics of South America were "young sisters of this government" and that he did not want European intervention in South America. The Credit Industriel and Peruvian Company groups , representing European and US lenders, had guaranteed the Provisional Peruvian Government of García Calderón that they would pay Peru's foreign debt and war reparations to Chile if Peru licenses the resources in Tarapaca forgave their societies. With the approval of the Peruvian government, both companies began lobbying against Tarapaca's assignment to Chile. In this case, Levi P. Morton , Bliss and Company would get the monopoly of nitrate sales in the USA. Levi P. Morton was a close friend of J. Blaime. Moreover, had Stephen A. Hurlbut , (Christiancys successor in Lima), the installation of a US Navy base in Chimbote reached and the licenses for the exploitation of coal resources in the interior, the latter, however, for his personal profit. These US attempts reinforced the provisional Peruvian government in its rejection of the assignment of Tarapaca. When it became public in the US that Hurlbut would benefit from US intervention in the war, it became clear that he was hindering the peace process. In late 1881, Blaine sent William H. Trescott to Chile to warn the government there that the United States was seeking arbitration to resolve the conflict and that wars did not justify border shifts.

After Garfield was murdered and Chester A. Arthur took office , Blaine was replaced by Frederick Theodore Frelinghuysen . Frelinghuysen felt that the US was unable to pursue Blaine's goals and changed the goals of Trescott's mission. The US historian Kenneth D. Lehmann says of US politics: “Washington had gotten into the middle of the controversy without considering a realistic position: the US moral apostle attitude had something hypocritical about its own history and the underlying threats not believable. "

UK politics

Regarding UK intervention in the war, British historian Victor Kiernan stated: “It must be stressed that the Foreign Office has never foreseen any kind of intervention. [...] It was particularly vigilant that no warships were smuggled to one of the parties because it feared that it would be drawn into an Alabama issue again. "

During the war, the British government confiscated four warships, two each that had been sold to Chile and Peru: the Arturo Prat (later Tsukushi ), Esmeralda (later cruiser Izumi ), Lima and the Topeka . The last two were built in the Howaldts works in Hamburg and were to be armed in England. They were named Socrates and Diogenes to disguise the true destination country.

Looting, war damage and war reparations

While the looting and war reparations are often forgotten in Chile, they are the cause of anti-Chilean resentment in Peru. The Chilean historian Milton Godoy Orellana distinguishes four cases:

- Looting after the battles of Chorrillos and Miraflores by members of the Chilean army

- Looting of the Peruvian capital triggered by the fear of its inhabitants of the advancing Chilean army

- The military confiscation of locomotives, railways, printing presses, weapons and other goods by the Chilean state. These expropriations were accepted in the 19th century. The Chilean government left its execution to the Oficina Recaudadora de las Contribuciones de Guerra , whose task was the inventory, confiscation, logging and the transport of the goods to Chile. A list of the confiscated goods does not exist, but many objects were noted in private and official letters, newspaper articles, cargo lists, etc.

- The confiscation of literary and artistic cultural assets from Peru

The drafting and adoption of international conventions on the protection of cultural property was not realized until the 19th and 20th centuries, but the conceptual beginnings were rooted in 18th century Europe. The Dear Code of 1863 placed cultural goods under protection during an armed conflict (Art. 35), but expressly allowed their use for reparation purposes (Art. 36) The Chilean historian Sergio Villalobos explains that the USA accepted the confiscation of cultural goods in 1871 but that Project of an International Declaration concerning the Laws and Customs of War of 1874 ( 1874 Project of an International Declaration concerning the Laws and Customs of War ) put this on the list of protected objects. In March 1881, around 45,000 books from the National Library of Peru were confiscated by the occupying power. Because many of these books were sold by Peruvians in Lima, it is a matter of dispute how many books actually belonged to the Chilean occupiers from the beginning. In late March 1881, the first books came to Chile and the local press started a discussion about the legitimacy of the confiscations of oil paintings, books, statues and other cultural goods. In a session of the Chilean parliament on January 4, 1883, the MP Augusto Matte Pérez asked the Minister José Manuel Balmaceda about the "shameful and degrading" shiploads of Peruvian cultural goods. The MP Montt demanded the return of the goods and was supported by his colleagues McClure and Puelma. The minister promised to end the confiscation of cultural goods and to return the objects mentioned in the debate about the legality of the confiscation of Peruvian cultural products. Apparently it did so because no more such shiploads arrived. But in 2007 Chile sent back 3,778 books to the Biblioteca Nacional del Peru. S. Villalobos took the view that there could be no excuse for theft.

A more complicated undertaking was the legal assessment of war damage to the property of citizens of neutral states. In 1884 the tribunals Tribunales Arbitrales were formed , each with one from Chile, one from the plaintiff's government and one from the government of Brazil appointed judge. They had to negotiate the claims of 118 British, 440 Italian, 89 French and from 1886 also German plaintiffs. The “Italian” tribunal also dealt with the Belgian and the “German” tribunal also with the Austrian claims. Citizens from the United States did not participate at the time and the Spanish lawsuits were negotiated directly with the Chilean government. Under the martial law of the time, lawsuits were filed by foreign citizens habitually resident in the national territory of the warring countries, complaints about damage in an area in which fighting had taken place (e.g. Arica, Chorrillos, Miraflores, Pisagua and Tacna) and damage caused by dispersed or marauding soldiers were not taken into account. Only 3.6% of the negotiated damages were recognized by the tribunal, which S. Villalobos attributes to the exaggeration of damages as a result of the hurt national sentiment of the Peruvians and the monetary interests of the foreign plaintiffs.

Horrors of war

Before the outbreak of war, the warring states promised to comply with the convention of the International Red Cross Committee of 1863 (see International Red Cross and Red Crescent Movement ) for the protection of war casualties, prisoners of war, refugees, civilians and other non-combatants, but did not adhere to it.

After the beginning of the war, an estimated 30,000 Chileans from Peru and Bolivia were deported to Chile and their property was confiscated; the majority of them had to seek shelter in pontoons, launches, and warehouses in Peruvian ports until they were shipped to Chile. It is estimated that 7,000 of them joined the military out of bitterness and vengeance. Peruvians and Bolivians living in Chile, however, remained completely unmolested.

Both sides accused each other of killing injured enemy soldiers after the fighting ended.

In addition to the Peruvian-Chilean battles in asymmetrical warfare after the occupation of Lima, latent social and ethnic conflicts erupted in Peru between the indigenous majority of the population, the Chinese coolies living in slavery-like conditions and the mestizo and white upper class. On July 2, 1884 in Huancayo the guerrilla leader Tomás Laymes and three of his men were convicted by a court in a zone controlled by Cáceres for the atrocities and crimes that the guerrillas had committed against the Peruvian people. In Ayacucho, the indigenous peoples rebelled against the "whites" and in Chincha there were expressions of displeasure among Afro-Peruvians against the large landowners of the Haciendas Larán , San José and Hoja Redonda . The Peruvian army finally succeeded in suppressing the rebellion by force. The Chinese coolies formed the Vulcano units within the Chilean army.

There was also ethnic tension between coolies and blacks. In the Cañete province, 2000 coolies from the Haciendas Montalbán and Juan de Arona were massacred by Afro-Peruvians .

consequences

War victims

The Five Years War is estimated to have cost between 14,000 and 23,000 lives. William F. Sater gives exact numbers and comes to well over 20,000 fatalities (see box at the beginning of the article). The economic and technical historian Günther Luxbacher calls the number of 14,000 fatalities.

Economic boom in Chile

As a result of the war, Chile took possession of the rich saltpeter deposits, which were also mined by British and German companies. In the following years Chile achieved considerable economic wealth. However, with the development of new processes for saltpetre extraction and the discovery of synthetic fertilizers at the beginning of the 20th century ( Haber-Bosch process ), saltpetre mining later lost its importance.

Burden on relations between the states involved

As a result of the war, which ended more than 130 years ago, the relationship between the former warring parties was deeply disturbed and permanently strained, with long-term political consequences. During the Second World War , Chile, contrary to its policy of neutrality, abruptly broke off relations with the Axis powers in 1943, not least because of the fear of a rapprochement between Peru and Bolivia and the United States. Chile's fear was that the determined support of both countries for the USA and the resulting US military aid could enable Peru and Bolivia to take action against Chile with the support of the USA, if Chile did not also join the allied camp.

The shameful defeat of Bolivia and Peru aroused persistent resentment and a desire for revenge against Chile in both countries, and despite the peace treaties that have existed for many years, the relationship between the three states is still strongly shaped by the past. Since the peace treaty of 1904, Bolivia blames the loss of sea access for its weak political and economic situation and calls for a revision of the treaty and a sovereign corridor to the sea. In 1920, Bolivia asked the League of Nations to change the border treaty, but the latter refused on the grounds that drawing the border was a task for the countries involved. Since then, all attempts at a diplomatic solution have failed, and Bolivia has not exchanged ambassadors with Chile since 1962. In order to substantiate its claim, Bolivia maintains the largest naval forces of any landlocked country worldwide ( Armada Boliviana ).

The Bolivian position is viewed by domestic and foreign observers as predominantly motivated by domestic politics, as Bolivia has free port rights and the right to duty-free transit of goods via Arica and Iquique based on the peace treaty, which Chile has always respected. Bolivia therefore has access to the Pacific for the movement of goods, so that the Bolivian private sector itself sees little need for action. Political representatives of all directions represented in the country consider a sovereign sea access to Bolivia with its own Pacific port as indispensable. Since the privatization of the Chilean port operations in Arica and the accession of Evo Morales to government in Bolivia, political tensions have intensified and the issue has become a perennial issue in Bolivia. An important argument of the current Morales administration is the lack of Bolivian sovereignty over the port facilities. In their view, these are inefficient due to a lack of sufficient investment and no longer able to cope with the country's growing exports. Appropriate modernization measures could therefore be carried out under Bolivian sovereignty, which are not a priority for Chile.

Since 1975, Chile has made various proposals for reconciliation with Bolivia, but these failed because of the Peruvian stance: The core of the negotiations between Chile and Bolivia was the cession of a corridor in the far north of Chile along the border with Peru, as Chile was divided by a corridor further south would. Such a northern corridor would lead over former Peruvian territory; however, according to the Treaty of Ancón , Chile can only cede former Peruvian territory to third parties with the consent of Peru.

From Peru's point of view, there is no reason to agree to such an assignment without consideration from Bolivia (since Bolivia would otherwise "benefit" from the Peruvian territorial losses). In Bolivia's view, however, the loss of access to the Pacific is a historical injustice that Chile alone is morally obliged to remedy; Bolivia sees no reason to have to buy the right to which it is entitled by making payments to Peru. From the perspective of Chile, the proposed swap of territory is already a concession to Bolivia without any direct benefit for one's own country; it is Bolivia's job to get Peru's approval.

After the failure of negotiations on a corresponding exchange of territory (Peruvian veto) and water rights on the Río Lauca in 1978, Bolivia completely broke off diplomatic relations with Chile. To this day, both countries officially only maintain contacts at consular level. Bolivia refuses to supply Chile with natural gas and makes gas supplies to Argentina conditional on Argentina not supplying this gas to Chile. Chile showed itself to be largely buttoned up towards later diplomatic initiatives to resolve the conflict.

In 2002, out of consideration for domestic political resistance, Bolivia refrained from investing billions of euros by foreign companies in the export of liquefied natural gas to the USA, because the gas was to be exported through pipelines via Chile (and Chile would therefore have benefited from the Bolivian gas).

After Chilean President Michelle Bachelet took office , there were again talks at government level between Bolivia and Chile on 13 points between 2006 and 2010, including the improvement of Bolivian goods transfers from the Chilean port to Bolivia (point 6 on the agenda). Talks broke off in 2010 after Bolivia announced in March that it would bring its claims to the International Court of Justice . Chile categorically excludes an assignment of territory. The situation is currently still unresolved and a diplomatic solution does not seem in sight.

The bilateral relationship between Peru and Chile is less strained at the official level, especially since Peru's Bolivian demands are only supported with reservations. Many actors in Peru consider it excessive and accuse Bolivia of first dragging Peru into the war in 1879 and then abandoning it. Peru suffered far more from the immediate effects of the war than Bolivia: “No Chilean soldier has set foot on the Bolivian highlands, let alone Sucre or La Paz . The main enemy of Chile was Peru. From 1881 Bolivia was only a spectator in the Pacific War. ”This is why the Peruvian-Bolivian relationship is historically burdened.

In the course of the proceedings before the International Court of Justice in The Hague, which began in 2008 to clarify remaining disputes about the maritime border between Peru and Chile, which the parties saw as a sign of the maturation of their relations, Peru definitively recognized the land border with Chile drawn in the peace treaty. The ruling of the court on January 27, 2014 was accepted by both sides and, on the first anniversary in January 2015, was recognized by the Peruvian President Ollanta Humala as the beginning of a new common future.

Remembrance day

May 21st is celebrated in Chile as a national holiday commemorating the naval battle of Iquique . In Iquique, conquered by Chile at the end of 1879, and in the capital Santiago, military parades and celebrations are held in honor of the war hero Arturo Prat , and the President presents the annual State of the Union report to parliament . The participation of representatives of the Peruvian Admiralty in the Chilean celebrations for "Iquique Day" in 2012, intended as a gesture of friendship, led to violent protests from nationalist circles in Peru. Such contacts and mutual appreciation have been common practice among church representatives for several years.

See also

- Timeline of the Saltpeter War

- History of Peru

- History of Chile

- History of Bolivia

- Chaco War

- Miguel Gray

- Arturo Prat

- Day of the Sea (Bolivia)

literature

English

- Thomas F. O'Brien: The Antofagasta Company: A Case Study of Peripheral Capitalism. In: Hispanic American Historical Review. Duke University Press 1980

- Gonzalo Bulnes: Chile and Peru: The causes of the War of 1879. Imprenta Universitaria, Santiago de Chile 1920 ( archive.org )

- William Jefferson Dennis: Documentary history of the Tacna-Arica dispute. In: University Iowa City (Ed.): University of Iowa studies in the social sciences . Iowa, USA 1927 ( limited preview in Google Book search). Copies of important original documents in Spanish and English, Volume 8 of the collective work.

- Bruce W. Farcau: The Ten Cents War. Chile, Peru and Bolivia in the War of the Pacific, 1879–1884. Praeger Publishers, Westport, Connecticut, London 2000, ISBN 0-275-96925-8 ( limited preview in Google Book Search)

- Victor Kiernan: Foreign Interests in the War of the Pacific. In: Hispanic American Historical Review XXXV, Duke University Press, 1955.

- William F. Sater: Andean Tragedy: Fighting the War of the Pacific, 1879-1884. University of Nebraska Press, Lincoln & London 2007, ISBN 978-0-8032-4334-7

- William F. Sater: Chile and the War of the Pacific. University of Nebraska Press, Lincoln & London 1986, ISBN 0-8032-4155-0

- William F. Sater: Chile During the First Months of the War of the Pacific. In: Journal of Latin American Studies, Cambridge University Press, 1973

- Robert L. Scheina: Latin America's Wars: The age of the caudillo, 1791-1899. Potomac Books, 2003, ISBN 978-1-57488-450-0 .

Spanish

- Diego Barros Arana : Historia de la guerra del Pacífico (1879-1880). Vol. 1, Santiago de Chile 1881 ( archive.org )

- Diego Barros Arana: Historia de la guerra del Pacífico (1879-1880). Vol. 2, Santiago de Chile 1881 ( archive.org )

- Jorge Basadre: Historia de la República del Perú: La guerra con Chile.

- Roberto Querejazu Calvo: Guano, Salitre y Sangre. Historia de la Guerra del Pacífico (Participación de Bolivia). La Paz 1979.

- Roberto Querejazu Calvo: Aclaraciones históricas sobre la Guerra del Pacífico. La Paz 1995.

- Republic of Chile: Boletin de la Guerra del Pacifico. Santiago de Chile 1879–1881 ( limited preview in Google Book search)

- Mariano Felipe Paz Soldán : Narración Histórica de la Guerra de Chile versus Perú y Bolivia. Imprenta y Libreria de Mayo, Buenos Aires 1884 ( archive.org )

- Sergio Villalobos: Chile y Perú, la historia que nos une y nos separa 1535–1883. Santiago de Chile, Editorial Universitaria, 2nd edition 2004, ISBN 9789561116016

Movies

- Caliche Sangriento , film, Chile, by Helvio Soto , 1969, 124 minutes.

- Amargo mar , Documental, Bolivia, by Antonio Eguino, 120 minutes.

- Epopeya , Documental, Chile, by Rafael Cavada, 2007

Web links

- New York Times : Bolivia Reaches for a Slice of the Coast That Got Away (about the aftermath in Bolivia)

Remarks

- ^ A b William F. Sater: Andean Tragedy. Tables 22 and 23 on p. 348 f. Additional information: 9,103 soldiers from the Peru and Bolivia Alliance were captured (no information on Chilean prisoners and deserters).

- ↑ Basadre Grohmann, Jorge (1964): Historia de la República del Perú. La guerra con Chile. Lima, Perú: Peruamerica SA, Cap. I (Apreciación sobre el estallido del conflicto chileno-boliviano), p. 35: «El gobierno de Daza violó la convención de 1873 y el treadado de 1874 al crear el impuesto de los diez centavos. Ante las reclamaciones, debió, sin duda, (como creyó Prado) aplazar la ejecución de esta ley y aceptar el arbitraje. Pero no sólo esquivó esas fórmulas sino optó por la decisión violenta de rescindir el contrato celebrado con la compañía salitrera que protestaba contra el gravamen, y de incautarse de las propiedades de ella […] »

- ^ William F. Sater (2007): Andean Tragedy: Fighting the War of the Pacific, 1879-1884. Lincoln and London: University of Nebraska Press. ISBN 978-0-8032-4334-7 , p. 28: “The company reacted predictably: citing the 1874 treaty, which explicitly prohibited the Bolivian government from taxing Chilean companies exploiting the Atacama Desert, the miners demanded that Daza rescind the impost”

- ^ The Cambridge History of Latin America , Volume III. Leslie Bethell, Cambridge University, 2009, p. 611 .: “the additional export tax of ten centavos per quintal suddenly imposed by the bolivians in 1878 was clearly a breach of faith.”

- ↑ Hugo Pereira, en La política salitrera del Presidente Prado : “La crisis definitiva se inició el 14 de febrero de 1878, cuando el dictador boliviano Hilarión Daza, agobiado por la crisis internacional, decidió poner un impuesto de diez centavos a cada quintal del salitre exportado desde Atacama, en clara violación del tratado de 1874 »

- ↑ Jorge Basadre, La Guerra con Chile, p. 7 (internet version), Cap. I (La solicitud boliviana para la alianza con el Perú y el treaded Lindsay-Corral): "El treaded Corral-Lindsay fue muy mal visto por el gobierno y por la prensa Peru. Aconsejó aquél al de Bolivia insistentemente que lo denunciara, así como elertrado de 1866, con el propósito de obtener un arreglo mejor o de dar lugar, con la ruptura de las negociaciones, a la mediación del Perú y de la Argentina. "

- ↑ Jorge Basadre, La Guerra con Chile, 1964, p. 8 (internet version), Cap. I (Significado del tratado de la alianza)

- ↑ Querejazu Calvo, Roberto (1979): Guano, Salitre y Sangre. La Paz-Cochabamba, Bolivia: Editorial los amigos del Libro, p. 122.

- ↑ La misión Balmaceda: asegurar la neutralidad argentina en la guerra del Pacífico , del 2 mayo del 2015

- ↑ Querejazu Calvo, Roberto (1979): Guano, Salitre y Sangre. La Paz-Cochabamba, Bolivia: Editorial los amigos del Libro. P. 726.

- ↑ Manuel Ravest Mora: La Casa Gibbs y el Monopolio Salitrero Peruano, 1876–1878 . Historia N ° 41, Vol. I, enero-junio 2008, p. 69 ( online )

- ↑ Luis Ortega: Los Empresarios, la política y los orígenes de la Guerra del Pacífico . Flacso, Santiago de Chile, 1984, p. 17.

- ^ Thomas F. O'Brien (1980): The Antofagasta Company: A Case Study of Peripheral Capitalism . Duke University Press: Hispanic American Historical Review, p. 13.

- ↑ Manuel Ravest Mora: La Casa Gibbs y el Monopolio Salitrero Peruano, 1876–1878 . Historia N ° 41, Vol. I, enero-junio 2008, p. 64.

- ↑ Enrique Merlet Sanhueza: Juan José Latorre: héroe de Angamos . Editorial Andrés Bello, 1997, p. 31 (accessed June 23, 2015).

- ^ William F. Sater: Chile and the War of the Pacific. P. 6: “The increase of taxes on the Compañia de Salitres y Ferrocarril clearly violated the 1874 treaty.”

- ↑ Bruce W. Farcau, The Ten Cents War , p. 41: “The very fact that the legislature in La Paz found it necessary to vote in what they claimed was a strictly municipal issue when the tax was first levied implied that the conflict with the 1874 treaty was clearly seen and that a conscious precedent was being set ”

- ↑ Ronald Bruce St. John, The Bolivia-Chile-Peru Dispute in the Atacama Desert , p. 12 f.

- ^ William F. Sater (2007): Andean Tragedy: Fighting the War of the Pacific, 1879-1884. Lincoln and London: University of Nebraska Press, ISBN 978-0-8032-4334-7 , p. 37

- ↑ Bruce W. Farcau: The Ten Cents War , p. 42: “on 27 February, the Bolivian legislature issued the authorization for a declaration of war, although the formal declaration would not be forthcoming until 14 March”.

- ^ William F. Sater: Andean Tragedy: Fighting the War of the Pacific, 1879-1884 , University of Nebraska Press, 2007, ISBN 978-0-8032-4334-7 , p. 28: "Two weeks after the Chilean occupation of Antofagasta [= on March 1st], he [Hilarion Daza] declared that Chile had imposed 'a state of war' on Bolivia. Apparently this decree did not constitute a formal declaration of belligerence [...]. "

- ^ William Jefferson Dennis: Documentary History of the Tacna-Arica dispute , University of Iowa studies in the social sciences, Vol. 8, p. 69: “On March 14 Bolivia advised representatives of foreign powers that a state of war existed with Chile. […] Godoi advised President Pinto that this move was to prevent Chile from securing armaments abroad […] ”

- ^ William F. Sater: Andean Tragedy: Fighting the War of the Pacific, 1879-1884. University of Nebraska Press, 2007, ISBN 978-0-8032-4334-7 , p. 113 f .: “There are numerous differences of opinion as to the ships' speed and armament. Some of these differences can be attributed to the fact that the various sources may have been evaluating the ships at different times. "

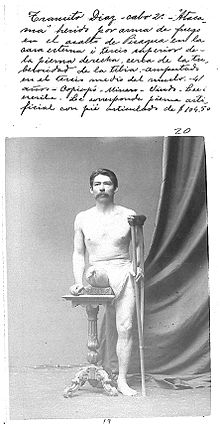

- ↑ Newspaper report on an exhibition of 30 of the 130 photos at the Universidad Católica Andrés Bello in Venezuela (excerpt with two photos), in: El Mercurio , April 28, 2002 archive.org ( Memento of March 7, 2007 in the Internet Archive )

- ↑ Documentation of the photo ( page no longer available , search in web archives ) Info: The link was automatically marked as defective. Please check the link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. soberaniachile.cl

- ↑ Bruce W. Farcau (2000). The Ten Cents War. Chile, Peru and Bolivia in the War of the Pacific, 1879–1884. Westport, Connecticut, London: Praeger Publishers. ISBN 978-0-275-96925-7 . P. 152: “Lynch's force consisted of the 1 ° Line Regiment and the Regiments 'Talca' and 'Colchagua', a battery of mountain howitzers, and a small cavalry squadron for a total of twenty-two hundred man”

- ↑ Diego Barros Arana (1881b). Historia de la guerra del Pacífico (1879–1880) , Volume II. Santiago, Chile: Librería Central de Servat i Ca. P. 98: «[El gobierno chileno] Creía entonces que todavía era posible demostrar prácticamente al enemigo la imposibilidad en que se hallaba para defender el territorio peruano no ya contra un ejército numeroso sino contra pequeñas divisiones. Este fué el objeto de una espedicion que las quejas, los insultos i las lamentaciones de los documentos oficiales del Perú, i de los escritos de su prensa, han hecho famosa. »

- ↑ Diego Barros Arana (1881a). Historia de la guerra del Pacífico (1879–1880) , Volume I. Santiago, Chile: Librería Central de Servat i Ca .: “Bluntschli (Derecho internacional codificado) dice espresamente lo que sigue: Árt. 544. Cuando el enemigo ha tomado posesión efectiva de una parte del territorio, el gobierno del otro estado deja de ejercer alli el poder. Los habitantes del territorio ocupado están eximidos de todos los deberes i obligaciones respecto del gobierno anterior, i están obligados a obedecer a los jefes del ejército de ocupación. »

- ^ Johann Kaspar Bluntschli: Le droit international codifié . Guillaumin et Cie., 1870, pp. 290-.

- ^ Sergio Villalobos: Chile y Perú, la historia que nos une y nos separa 1535–1883. 2nd edition 2004. Santiago: Editorial Universitaria. ISBN 978-956-11-1601-6 , p. 176

- ↑ Farcau, The Ten Cents War (2000)

- ^ Lawrence A. Clayton: Grace: WR Grace & Co., the Formative Years, 1850-1930 . Lawrence Clayton, 1985, ISBN 978-0-915463-25-1 .

- ↑ a b Kiernan, Victor (1955). Foreign Interests in the War of the Pacific XXXV (pp. 14-36 ed.). Duke University Press: Hispanic American Historical Review.

- ↑ Mauricio E. Rubilar Luengo: Guerra y diplomacia: las relaciones chileno-colombianas durante la guerra y postguerra del Pacífico (1879–1886) , Revista Universum Vol. 19, No. 1/2004, pp. 148–175, doi = 10.4067 / s0718-23762004000100009

- ↑ a b c d e Kenneth Duane Lehman (1999): Bolivia and the United States: A Limited Partnership. University of Georgia Press. ISBN 978-0-8203-2116-5 , url = http://books.google.com/books?id=ATv_VPFez5EC

- ^ A b c Fredrick B. Pike: The United States and the Andean Republics: Peru, Bolivia, and Ecuador . Harvard University Press, January 1, 1977, ISBN 978-0-674-92300-3 .

- ^ William F. Sater: Andean Tragedy: Fighting the War of the Pacific, 1879-1884. University of Nebraska Press, 2007, ISBN 978-0-8032-4334-7 , pp. 304-306: “The anglophobic secretary of state”

- ^ Jorge Basadre: Historia de la Republica del Peru, La guerra con Chile (Spanish). Peruamerica SA, Lima, Peru 1964. Chapter 9, p. 16 (Internet version)

- ^ William F. Sater: Andean Tragedy: Fighting the War of the Pacific, 1879-1884. University of Nebraska Press, 2007, ISBN 978-0-8032-4334-7 , pp. 304-306

- ^ Jorge Basadre: Historia de la Republica del Perú, La guerra con Chile (Spanish). Peruamerica SA, Lima, Peru 1964. Chapter 9, p. 14 (Internet version)

- ↑ Rafael Mellafe Maturana: La ayuda inglesa a Chile durante la Guerra del Pacífico. ¿Mito o realidad? In: Cuaderno de historia militar, ed. Departamento de historia militar del Ejército de Chile, No. 12, December 2012, p. 69

- ↑ Milton Godoy Orellana: "Ha traído hasta nosotros desde territorio enemigo, el alud de la guerra": Confiscación de maquinarias y apropiación de bienes culturales durante la ocupación de Lima, 1881–1883 , in: Historia (Santiago) 2011, vol. 44 , No. 2, pp. 287-327 ISSN 0717-7194 .

- ↑ Andrera Cunning: The Safeguarding of Cultural Property in Times of War & (and) Peace .., Tulsa Journal of Comparative and International Law, 2003, Vol 11, No. 1, Article 6, http: //digitalcommons.law.utulsa. edu / tjcil / vol11 / iss1 / 6 / , p. 214

- ↑ Andrea Gattini, Restitution by Russia of Works of Art Removed from German Territory at the End of the Second World War , http://www.ejil.org/pdfs/7/1/1356.pdf , p. 70

- ↑ a b c d e f g Sergio Villalobos: Chile y Perú, la historia que nos une y nos separa 1535–1883. 2nd edition 2004. Santiago: Editorial Universitaria. ISBN 978-956-11-1601-6 .

- ↑ Dan Collyns: Chile returns looted Peru books , BBC. November 7, 2007. Retrieved November 10, 2007.

- ^ William F. Sater (2007): Andean Tragedy: Fighting the War of the Pacific, 1879-1884. Lincoln and London: University of Nebraska Press. ISBN 978-0-8032-4334-7

- ↑ a b Francisco Antonio Encina, “Historia de Chile”, p. 8, quoted in Valentina Verbal Stockmeyer, “El Ejército de Chile en vísperas de la Guerra del Pacífico”, Historia 396 ISSN 0719-0719 N ° 1 2014 [135– 165], p. 160

- ^ A b Hugo Pereira, Una revisión histográfica de la ejecución del guerrillero Tomás Laymes , in Trabajos sobre la Guerra del Pacífico , Pontificia Universidad Católica del Perú. P. 269 ff.

- ↑ Oliver García Meza: Los chinos en la Guerra del Pacífico , in: Revista Marina ( PDF )

- ↑ Bruce W. Farcau (2000). The Ten Cents War. Chile, Peru and Bolivia in the War of the Pacific, 1879–1884. Westport, Connecticut, London: Praeger Publishers. ISBN 978-0-275-96925-7

- ↑ Ramon Aranda de los Rios, Carmela Sotomayor Roggero: Una sublevación negra en Chincha: 1879 , in: La Guerra del Pacífico , vol. 1. Wilson Reategui, Wilfredo Kapsoli & others, Universidad Nacional Mayor de San Marcos, Lima 1979, p. 238 ff.

- ↑ Wilfredo Kapsoli, El Peru en una coyuntura de crisis, 1879-1883 , p. 35 f. in “La Guerra del Pacífico”, Vol. 1, Wilson Reategui, Wilfredo Kapsoli & others, Universidad Nacional Mayor de San Marcos, Lima 1979

- ^ William F. Sater, University of Nebraska Press (Ed.): Andean Tragedy: Fighting the War of the Pacific, 1879-1884 . Lincoln and London 2007, ISBN 978-0-8032-4334-7 .

- ↑ a b c d e f Dry exercises on Lake Titicaca , report on the Bolivian Navy in the FAZ from June 23, 2014.

- ↑ Günther Luxbacher, explosives or bread? , in: Damals , edition 8/2002, p. 61

- ↑ Thomas M. Leonard, John F. Bratzel: Latin America during World War II , Rowman & Littlefield: Plymouth 2007 ( limited preview ), p. 162: “… a more pressing argument for cooperation was the fear that Bolivian and Peruvian support for the United States would lead to US military assistance and diplomatic backing of those two rivals' claims against Chile. "

- ↑ a b Estado de los 13 puntos entre Bolivia y Chile (“On the status of the 13 points between Bolivia and Chile”), press release from March 23, 2011 (only title line, mirrored on info-bolivia.com, original no longer available, see above accessed in April 2015).

- ↑ a b The problematic relations between Bolivia, Chile and Peru , article by Eduardo Paz Rada in the online magazine Quetzal (March 2011), accessed in April 2015.

- ↑ Vicecanciller boliviano cuestiona capacidad del Puerto de Arica portalportuario.cl, February 24, 2015

- ↑ Bolivia wants to sue for access to the Pacific. In: ORF . March 24, 2011, accessed March 24, 2011 .

- ↑ Alejandro Iturra: Chile - Bolivia: La agenda de 13 puntos se redujo a uno ("Chile - Bolivia: 13-point agenda is reduced to one point"), Instituto Igualdad , July 5, 2011.

- ↑ Volkmar Blum: Hybridization from below: Nation and society in the central Andean region. LIT Verlag: Münster 2001, p. 89.

- ↑ See Federal Foreign Office : Country Report Bolivia, Section Foreign Policy (status: October 2014), accessed in April 2015.

- ↑ Chile y Perú han dado un ejemplo claro de madurez (“Chile and Peru have set a clear signal for maturity”), press release on Emol.com, accessed in April 2015.

- ↑ Obispos de Chile y Perú participaron en homenaje a héroe peruano (“Bishops from Chile and Peru took part in the appreciation of the Peruvian national hero [Miguel Grau]”), report on the online platform of the Chilean Bishops' Conference (iglesia.cl) from March 6th 2006, accessed April 2015.