LZ 129

| LZ 129 "Hindenburg" |

|

|---|---|

LZ 129 Hindenburg in Lakehurst , 1936 |

|

| Type: | Rigid airship |

| Design country: | |

| Manufacturer: | |

| First flight: |

March 4, 1936 |

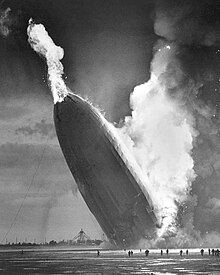

The Zeppelin LZ 129 "Hindenburg" (registration D-LZ129), named after the German President Paul von Hindenburg , was one of the two largest aircraft ever built , along with its sister airship LZ 130 . Its maiden voyage was in March 1936. On May 6, 1937, it was destroyed on landing in Lakehurst (New Jersey, USA) when the hydrogen filling ignited. 35 of the 97 people on board as well as a member of the ground crew were killed.

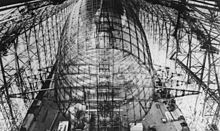

The ship

The frame of LZ 129 was made of duralumin , a very strong aluminum alloy. The ship was 245 meters long, had a diameter of 41.2 meters and a gas volume of 200,000 cubic meters. Its average cruising speed was 100–120 km / h, its cruising altitude 400–600 meters, often only 200 meters.

In contrast to previous zeppelins, the rooms for the passengers on LZ 129 were on two decks inside the float. However, this arrangement of the passenger facility was not new. The British rigid airships R100 and R101 already had this type of passenger accommodation inside the hull. So more space could be made available. The downsizing of the gondola , which was now only used to steer the airship, also reduced the ship's drag . The facilities for passenger transport were called the passenger facility. This was located about midships and had port and starboard windows sloping downwards. Two stairs that could be swiveled down made it easy to get on and off the floor.

The chief designer of the LZ 129 was Ludwig Dürr . The interior was designed by the German architect Fritz August Breuhaus de Groot , who designed it with his then colleague Cäsar F. Pinnau . Initially there were 25 sleeping cabins with 50 beds available for passengers, and 72 beds after the expansion in the winter of 1936/37. The upper main deck (A-deck) was approx. 22 m wide and 14 m long. It contained a large dining room with a promenade on one side and a foyer and a writing and reading room on the other. Ten additional cabins with windows (one for four people) were installed behind the B-deck. There were 54 beds for the crew. After the airship conversion, the crew was designed to be a maximum of 61 crew members. The cabins of the LZ 129 each had a double bunk bed, a washbasin with hot and cold water that could be folded into the wall and a button to call the staff. Compared to the luxurious cabins of an ocean liner, the heated cabins of the LZ 129 were extremely spartan and more like comfortable sleeping compartments; therefore the passengers spent most of their time in the other rooms of the passenger facility.

Galleries were set up along the hull, which allowed a view downwards and of the landscape; some windows could also be opened. There was also a smoking parlor on the lower deck. It had its own ventilation, which, for safety reasons, created a slight overpressure so that no flammable gases could penetrate from the outside. There was also the only lighter on board, managed by the steward . A small bar was set up in front of the smoking room. The rest of the B-deck was mainly equipped with toilets, the electric kitchen with a dumbwaiter and the crew and officers mess. The crew quarters were outside the passenger facility in the hull of the ship. There were also showers here - for the first time on an airship. The food, which was served to the mostly wealthy passengers, consisted of fine dishes and wines and soon had a very good reputation.

Famous also was Blüthner - wing . The musical instrument was carried on some trips and was specially made for LZ 129. Like the ship, it was mostly made of aluminum and covered with yellow pigskin. The wing weighed only about 180 kg. However, it was removed in the course of the conversion to the higher passenger capacity for weight reasons. In 1943 the instrument was destroyed in a bomb attack on Leipzig.

Emergence

One reason for the size of the LZ 129 was the planned use of helium as a lifting gas to replace the highly flammable hydrogen . The originally planned successor to the extremely successful LZ 127 "Graf Zeppelin" , the Zeppelin LZ 128 , was not realized after the loss of the English airship R101 , which was hit by a hydrogen fire after the emergency landing. In its place came the construction of LZ 129 "Hindenburg", which was again enlarged for the use of helium. At the time, the USA was the only supplier of helium. They had issued a ban on exporting helium. Nevertheless, during the planning phase of the Hindenburg , Hugo Eckener was given the prospect of the delivery of helium. In 1929 he even had a conversation with the American President in the White House about this. Against the background of the rising National Socialism and the fear that helium could make an airship fit for war, the USA decided not to supply helium. It was therefore decided to operate the LZ 129, like all previous German zeppelins, with hydrogen.

Planning began in autumn 1930 on the basis of LZ 128. In autumn 1931 construction began. After about five years, the first workshop trip took place on March 4, 1936, during which the ship was still unbaptized. The trip lasted three hours and took 87 people across Lake Constance. From a technical perspective, the tests were successful. On both sides of the ship, on this first voyage, the five interlocking Olympic rings advertised the 1936 Olympic Games in Berlin.

technology

Dimensions and measurements

LZ 129 "Hindenburg" had 15 main rings with a distance of around 15 m each, which created space for 16 gas cells with a maximum volume of around 200,000 cubic meters. They were usually 95 percent filled with around 190,000 m³ of hydrogen. Two stern and two bow gas cells were connected to one another. LZ 129 "Hindenburg" had a nominal gas content of 190,000 m³ (impingement gas content of 200,000 m³).

The hull with a 36-sided cross-section was 246.7 meters long and 41.2 meters in diameter. Standing on the landing wheels, the ship was 44.7 meters high, the width with the propellers was 46.8 m. With these dimensions, it approached the volume of the Titanic (269.04 meters length, 66.5 meters height (dry), 28.19 meters width).

Of the total weight of up to 242 tonnes, around 118 t were curb weight. The normal service weight was around 220 t. The zeppelin was capable of carrying around 11 t of mail, freight and luggage. 88,000 liters of diesel fuel , 4500 liters of lubricating oil and 40,000 liters of water ballast could be carried. The fuel supply was stored in aluminum barrels that were carried along the side walkways.

Propulsion and flight performance

The LZ 129 was the first ever Zeppelin to be powered by diesel engines. Four of Daimler-Benz specially designed water-cooled sixteen-cylinder - V-engines 602 (-plant: LOF 6) of the type DB were attached to both sides of the hull in four streamlined gondolas. A compressed air system fed the landing gear struts and the echo sounder system and was used to start / reverse (forward / reverse) the engines. The compressed air tanks, which were located in the machine gondolas and on the two gondola rings at the keel entrance, could be refilled using switchable compressors. Electrical preheating of lubricating oil and cooling water was possible. A machinist in each of the gondolas monitored the engines.

The diesel engines were four-stroke engines with pre-chamber injection . A version modified as MB 502 (in-house: BOF 6) was used to propel speedboats of the Navy . Later it was further developed into the 20-cylinder MB 501/518 engine , which became a standard engine for marine (sea) ships after the war and was part of the MTU production program under the designation 20 V 672 until the 1970s . The DB 602 / LOF 6 has a displacement of 88.5 liters ( bore : 175 mm, stroke : 230 mm), a continuous output of 588 to 662 kW (800 to 900 PS) and a maximum output of 883 kW (1200 PS) . The nominal speed was 1400 min −1 .

As propellers four-bladed, made of wood came pusher propeller with a diameter of six meters of the propeller work Heine from Berlin-Friedrichshain used. They were driven by a Farman LZ gearbox that was attached directly to the engine and halved the number of revolutions. The ship reached a cruising speed of around 125 km / h and had a range of up to 16,000 km.

Shell

The gas cells were no longer made of gold bat skin , as in earlier zeppelins, but were coated with a gelatinous substance, similar to the ones previously used on the USS Akron and USS Macon . The gas permeability was only 1 l / m² in 24 hours.

The outer shell consisted of fabric, namely cotton sheets and linen , with a total area of approx. 34,000 m². For the purpose of greater weather resistance and better smoothness, it was coated several times with Cellon (an acetyl cellulose preparation). By adding aluminum powder to the paint, the shell was designed to be reflective for thermal protection. It also had an iron oxide pigment paint on the top inside to protect against ultraviolet rays .

useful information

- Two different methods were used to measure the speed of the airship. On the one hand, a measurement was made using a light beam. On the other hand, a loud whistle was used so that the speed of the airship was measured via the speed of sound propagation .

- Each passenger of the airship was calculated with a weight of 80 kg plus 20 kg baggage allowance. In addition, furnishings in the cabin, food and washing water were transferred per passenger, so that a passenger on a trip to South America was measured with an average weight of 300 kg.

- In addition to the passengers and the crew, the zeppelin also transported freight and mail. Letter envelopes were stamped by the Deutsche Zeppelin-Reederei (DZR).

Rides

1. Test drive

On March 4, 1936, the first test run of the airship "Hindenburg" with 85 people (55 crew, 30 passengers) from Friedrichshafen via Meersburg back to Friedrichshafen. The 180 kilometer journey from 3:19 p.m. to 6:25 p.m. was led by Ernst A. Lehmann , Hans von Schiller and Hugo Eckener . During the journey 1640 kg of fuel and 60 kg of lubricating oil were used.

On March 19, 1936, the LZ 129 was delivered to the Deutsche Zeppelin-Reederei (DZR).

Transatlantic service

After its commissioning, the Hindenburg was mainly used on the transatlantic routes from Germany (mostly from Frankfurt am Main) to Rio de Janeiro and to Lakehurst near New York. On March 31, the airship set out for the first time from Friedrichshafen- Löwental to Rio de Janeiro in Brazil. The commandant was Ernst A. Lehmann, and Hugo Eckener was also on board.

The first commercial passenger voyage to the USA started on the evening of May 6, 1936 at 9:30 p.m. in Frankfurt and ended after the record time of 61.5 hours on the morning of May 9 at 6:10 a.m. at the anchor mast at Lakehurst .

In total, LZ 129 “Hindenburg” drove ten times to the USA (Lakehurst) and seven times to Brazil (Rio de Janeiro) in 1936. In the first year of its commissioning, it carried 1,600 passengers across the Atlantic and accumulated 3,000 flight hours in the process. The average travel time to the USA was 59 hours, back because of the more favorable air currents only 47 hours. The airship was 87% fully booked on the way west and 107% on the return trip. Some additional passengers were accommodated in officers' cabins . Back then, a ticket cost $ 400-450 (round-trip $ 720-810, which is around $ 13,000-15,000 today).

For the beginning of 1937, nine additional cabins were installed on the B-deck, increasing the capacity to 72 passengers. This was made possible, among other things, by the increased buoyancy that the hydrogen lifting gas brought with it compared to the originally planned helium.

Balance sheet

From commissioning on March 4, 1936 to the accident on May 6, 1937, LZ 129 “Hindenburg” covered around 337,000 kilometers over 63 journeys.

The longest voyage of the airship took place from October 21 to 25, 1936 from Frankfurt am Main to Rio de Janeiro. The distance covered was 11,278 km with a driving time of 111.41 hours and an average speed of 101.8 km / h. The fastest journey was from Lakehurst to Frankfurt between August 10 and 11, 1936. A distance of 6732 km was covered in 43.02 hours. This corresponds to an average speed of 157 km / h. Favorable winds were responsible for this.

Special rides

- March 26-29, 1936: Joint trip to Germany with LZ 127 “Graf Zeppelin”. Among other things, leaflets were dropped for the National Socialists who used this trip as a propaganda event for the Reichstag election on March 29 ; 6676 km.

- During the opening ceremony of the 1936 Olympic Games on August 1st, the “Hindenburg” from Frankfurt drove over the fully occupied Olympic Stadium in Berlin. Shortly before Adolf Hitler appeared for the ceremony, the airship pulled the Olympic flag, attached to a long rope, across the stands; 1622 km.

- On October 9, 1936, a trip across the New England area started in the USA , to which the companies Colonial Esso , Standard Oil and the DZR had invited America's most influential and wealthy industrialists. This tour was therefore also known as the Millionaires Flight ; 1123 km.

"Hindenburg" disaster

Lakehurst accident

Delay and crash

The LZ 129 "Hindenburg" had an accident on May 6, 1937 while landing on the local airship port area during a line trip as part of the North American program of the DZR from Frankfurt am Main to Lakehurst ( New Jersey ) . The route led via Cologne (for the purpose of dropping mail at Cologne-Butzweilerhof airport ). A reporter in a US newsreel film uses the words "from Hamburg", but since the postcards that were dropped in Cologne were postmarked in Frankfurt am Main, Frankfurt am Main can be assumed to be the starting point of the disaster trip. The journey went - apart from the unfavorable weather conditions - without any special incidents. As a result of headwinds, the LZ 129 was delayed by ten hours. Because of the threat of a thunderstorm, the commander Max Pruss (1891–1960) drove in a circle for one and a half hours, so that the landing was delayed again considerably. When the zeppelin finally reached its position above the landing mast around 6:25 p.m. local time, a hydrogen fire broke out in the stern of the ship, and it spread rapidly. The airship lost its static buoyancy and sank to the ground in about half a minute. The flames also ignited the remaining diesel fuel carried for the drive engines.

Contemporary witness reports

The American reporter Herbert Morrison (1905–1989) described the mooring maneuver in a live report on site. He described the flames, the crash, warned the people on the ground, reported smoke and flames 150 meters high and thought of the passengers.

Victim

Causes of death were jumping from too great a height as well as burn injuries and burns. 35 (13 passengers, 22 crew members) of the 97 people (36 passengers, 61 crew members) on board and one member of the ground crew were killed (23 passengers and 39 crew members survived the accident). Ernst A. Lehmann was there as an observer for the management on this trip and died of burns the day after the accident. One of the fatalities among the passengers was the co-owner of the Teekanne company, Ernst Rudolf Anders . It was the first fatal accident in civil aviation with Zeppelin airships after the First World War. With the HAPAG steamer Hamburg , the remains of the crew and some passengers arrived in Cuxhaven on May 21, where a state ceremony was organized. Then the coffins were brought to their hometowns on a special train of the Reichsbahn . As in Friedrichshafen , where six crew members were buried at a funeral service on May 23rd with great public sympathy, there were also larger funeral ceremonies in the other places, especially in Frankfurt. Until then, there was no misfortune in modern aviation history for greater publicity.

monument

A memorial was later erected directly at the site of the accident. The work, consisting of polished stone slabs, is supposed to show the outline of the wreck of the Hindenburg in a simplified manner. It is edged with a heavy yellow anchor chain. In the center there is a dedication plaque reminding of the accident.

The seven Frankfurt victims were buried in a communal grave at the Frankfurt main cemetery. The tomb also serves as a memorial to the victims. It was built in 1939 by the sculptor Carl Stock and is now an honorary grave and is a listed building . According to the inscription on the memorial column, Fritz Flackus (Koch), Ernst Schlapp (electrician), Captain Ernst A. Lehmann (as an observer of the management of the Deutsche Zeppelin-Reederei (DZR) on board), Alfred Bernhardt (helmsman), Franz Eichelmann (radio operator), Willy Speck (first radio operator) and Max Schulze (steward) are buried. Ernst A. Lehmann was originally buried there as part of a state funeral , but in 1939 he was transferred to Grassau ( Chiemgau ), where his son was already buried and where the widow had moved.

Survivors

The captain of the airship Max Pruss (1891–1960) survived seriously injured and was marked by burn scars on his face for the rest of his life. The first officer Albert Sammt also suffered not inconsiderable burns, but was back in service as an airship operator in 1938 - as the commander of LZ 130 . Among the less severely affected crew members were flight attendant Heinrich Kubis and altitude helmsman Eduard Boëtius , who helped many passengers during the accident. On August 13, 2014, Werner Franz (* May 22, 1922), the last survivor of the occupation, died. The cabin boy on LZ 129 had served officers and captains and washed dishes. During the disaster, water from a tank ran over him, so that he had some protection from the flames and could jump out of the airship almost unharmed. However, he remained traumatized throughout his life. Werner Doehner (born March 14, 1929) survived him, who died on November 8, 2019 at the age of 90 as the last of the surviving passengers in a hospital in Laconia , New Hampshire . The only slightly injured passengers included Lieutenant Claus Hinkelbein and the acrobat Joseph Späh, who was subsequently suspected of sabotage .

Root cause research

Immediately after the disaster of May 6, 1937, the Reich Minister for Aviation Hermann Göring set up an investigative committee consisting of Hugo Eckener , Director Ludwig Dürr, Lieutenant Colonel Breithaupt, Professor Bock, Professor Dieckmann and Chief Airman Hoffmann. This published his report in 1938 in the journal Luftwissen (Vol. 5, 1938, No. 1, pp. 3–12).

Basically the following possibilities exist: 1. Gas leakage and sparks after the thunderstorm, possibly triggered by a spark on the anchor mast; 2. Sparks on the wet landing ropes thrown from the bow; 3. Elm fire as a result of electrostatic charges, e.g. B. on the specially prepared, partly rubberized outer covers; 4. Sabotage , e.g. B. by a bomb or an intentional slitting of the shell; 5. Operating errors / human error; 6. The smoking salon with a single lighter, kept separately by a steward. Conspiratorial sabotage theories were not tolerated by Hitler for psychological reasons of the vulnerability of the political and flight system, which means that, for reasons of diplomatic courtesy, the theories of force majeure and thunderstorm discharge prevailed. Nothing is said about bomb finds or detonator mechanisms.

Independently of this, the US Department of Commerce also set up a commission of inquiry. The extensive report (56 typewritten pages with four appendices) was submitted on July 21, 1937. It says in the abstract that the cause of the fire could have been the ignition of a gas-air mixture, which was most likely triggered by a clump discharge . No conclusive evidence of this has been presented.

The German report is a little more cautious, but also favors an electrical discharge as the cause of the disaster, possibly triggered by the wet landing ropes that were dropped. Ultimately, however, the cause of the accident remains open.

Here is an excerpt from the report of the German committee of inquiry:

- “If, therefore, one of the aforementioned criminal attack possibilities is not possible, the committee can only accept the coincidence of a number of unfortunate circumstances as a case of force majeure as the cause of the airship fire. In this case the following explanation of the accident appears to be the most likely:

- During the approach to landing, a leak occurred in cell 4 or 5 in the stern of the ship, perhaps due to the breakage of a tension wire, through which hydrogen gas flowed into the space between the cell and the shell. This created a combustible hydrogen-air mixture in the upper rear part of the ship.

- Two cases are conceivable for the ignition of this mixture:

- a) As a result of electrical atmospheric disturbances, the landing of the airship, the potential gradient near the ground was so high that after the entire ship was grounded at the point of its greatest elevation, namely at the stern, it led to cluster discharges and thus to ignition.

- b) After the landing ropes were dropped, the surface of the outer hull of the airship was less well earthed than the frame of the airship because of the lower electrical conductivity of the outer hull material. In the case of rapid changes in the atmospheric field, as is the rule in an after-thunderstorm and also in the present case, potential differences then arose between places on the outside of the shell and the framework. If these places were sufficiently moist, which was likely in the area of cells 4 and 5 as a result of the previous passage through a rainy area, these potential differences could bring about voltage equalization by a spark, which could possibly ignite the hydrogen present above cells 4 or 5 -Air mixture caused.

- Of the two explanations mentioned, the one described under b) appears to be the more likely. "

All available images were evaluated at the time, and all witnesses from the airship and many eyewitnesses to the disaster were questioned and the site of the accident was examined in detail. Precisely because of the political situation, the USA could not afford to proceed lightly in this investigation.

consequences

The destruction of the LZ 129 heralded the temporary end of commercial airship travel . Although it was only the fifth most serious accident to an airship in terms of the number of victims, this event burned itself into the memory of society - not least because of the legendary, extremely emotional radio report (it was only later connected to the film material) by Herbert Morrison as one of the great technology disasters of the 20th century. The newsreel report associated with Morrison's radio commentary was included in the US National Film Registry in 1997 as a film document that is particularly worth preserving .

Of the 17,609 items of mail that were on board, 368 survived the accident. These zeppelin mail items, some of which are marked by scorch marks, are today particularly popular with collectors.

The sister ship of the LZ 129, the LZ 130 "Graf Zeppelin II" , which was under construction at the time of the accident , was no longer in commercial use. However, the ship still undertook a few test and propaganda trips . With the beginning of the Second World War, the rigid airships ended. The two remaining zeppelins (LZ 127 and LZ 130), the last two rigid airships at that time, were scrapped.

Around 60 years after the Lakehurst disaster, the first Zeppelin airship of a new generation took off on September 18, 1997. The Zeppelin NT is currently the only airship with an internal frame, a so - called semi - rigid airship . It is filled with non-flammable helium .

Museum processing

The Zeppelin Museum in Friedrichshafen has a replica of part of the passenger system from LZ 129.

Postcards and letters

Fiction

- Phönix aus Asche , novel by Henning Boëtius from the year 2000. The protagonists of the novel represent the thesis of sabotage by the Nazis.

Movies

- 1975: The Hindenburg - feature film.

- 1980: Pictures that moved the world - documentary series, in the episode Airship Hindenburg - Fire and Crash (Season 1, Episode 7) the Hindenburg disaster is dealt with.

- 1998: X-Factor: The Inconceivable - Mystery Series, in The Zeppelin (Season 2, Episode 11) the misfortune of Lakehurst is taken up in a fictional story.

- 2000: Höllenfahrten - Documentation series, in the episode Titanic of the Skies - The Hindenburg's last ride (episode 11) the Hindenburg disaster is dealt with.

- 2005: Seconds before the accident - documentary series, in the episode Journey to Death - The End of the Hindenburg (Season 2, Episode 12) the Hindenburg disaster is dealt with.

- 2007: MythBusters - Die Wissensjäger - the episode A Burning Airship (Season 5, Episode 1) deals with the misfortune.

- 2011: Hindenburg - TV film.

- 2011: The last hours of the Hindenburg documentation.

- 2011: ZDF-History - Documentation series, in the episode Hindenburg - The true story , the story of the Zeppelin LZ 129 "Hindenburg" is dealt with.

- 2016: Timeless - TV series, in season 1, episode 1, the Hindenburg disaster is the theme.

Trivia

The Hindenburg Omen is named after the Hindenburg disaster, a constellation on the stock exchanges that is supposed to predict upcoming slumps. The British rock band Led Zeppelin used the burning Hindenburg for their first record cover .

See also

literature

- Rick Archbold, Ken Marschall: Airship Hindenburg and the great time of the zeppelins. Bassermann, Munich 2005, ISBN 3-8094-1871-4 .

- Eugen Bentele: A Zeppelin machinist tells the story. My journeys 1931–1938. Städtisches Bodensee-Museum, Friedrichshafen 1990, ISBN 3-926162-56-2 .

- Rolf Brandt: Zeppelin world trips. Book III: LZ 129 Hindenburg. Greiling cigarette factory, Dresden 1937.

- Harold Dick, Douglas Robinson: The Golden Age of the Great Passenger Airships Graf Zeppelin and Hindenburg. Smithsonian Institution Press, Washington, DC / London 1985, pp. 85, 220 (English).

- WE Dörr: The Zeppelin airship "LZ 129". In: Journal of the Association of German Engineers, Volume 80, No. 13, March 28, 1936, p. 379 (reprinted in: P. Kleinheins: Die große Zeppeline. Springer-Verlag, Berlin / Heidelberg 2005, p. 165.

- Saskia Frank: Zeppelin events. Technical disasters in the media process. Tectum, Marburg 2008, ISBN 978-3-8288-9836-3 (also: Dissertation Uni Marburg 2007).

- Peter Kleinheins (ed.): The large zeppelins. The history of airship construction 3rd edition. Springer, Berlin 2005, ISBN 3-540-21170-5 .

- Werner von Langsdorff: LZ 129 "Hindenburg". The airship of the German people. Bechhold, Frankfurt am Main 1936.

- Ernst A. Lehmann: On air patrol and world travel. Schmidt & Günther, Leipzig 1936.

- Stephan Martin Meyer, Thorwald Spangenberg: With the Zeppelin to New York. The story of the cabin boy Werner Franz. Gerstenberg, Hildesheim 2016, ISBN 978-3-8369-5884-4 .

- John Provan : The Hindenburg - a Ship of Dreams. John Provan, Kelkheim 2011 (Amazon kindle e-book, English).

- Gudrun Ritscher: Working on an airship. The crews of the passenger airships LZ 127 "Graf Zeppelin" and LZ 129 "Hindenburg". In: Scientific yearbook of the Zeppelin Museum Friedrichshafen. Gessler, Friedrichshafen 2005, pp. 78–99.

- Lutz Tittel (Ed.): LZ 129 "Hindenburg". 4th edition. Städtisches Bodensee-Museum, Friedrichshafen 1997, ISBN 3-926162-55-4 .

- Lutz Tittel: 1936–1937 LZ 129 “Hindenburg / 1937–1987 50 years of the Lakehurst accident. In: Writings on the history of Zeppelin airship travel. No. 5. Gessler, Friedrichshafen 1987, ISBN 3-926162-55-4 .

- Lutz Tittel: LZ 129 "Hindenburg". Zeppelin Museum Friedrichshafen, Friedrichshafen 1997, p. 19.

- Barbara Waibel: LZ 129 Hindenburg. Luxury liner of the skies. Sutton, Erfurt 2010, ISBN 978-3-86680-585-9 .

Web links

- LZ-129 Hindenburg at airships.net (English)

- Project LZ 129 , blog by Patrick Russell on LZ 129 (English)

- Faces of the Hindenburg , Patrick Russell's blog on all 97 people on board the last voyage

- Report of the German committee of inquiry (1937) (see also two sketches from the report at the end of the following article )

- Description of the criticism of Bains IPT (English)

- H. Busch: radio equipment and direction finding system of the LZ 129

- Addison Bain, Ulrich Schmidtchen: A myth burns up - why and how the "Hindenburg" burned down ( Memento from May 30, 2015 in the Internet Archive ) (a widespread false theory)

- Silent film about the explosion of the Hindenburg in the Internet Archive (Source: Prelinger Archives )

- Radio conversation between the Reichsender Hamburg and the LZ 129, March 27, 1936

- Funeral service in Friedrichshafen for the dead of the Lakehurst disaster , a speech by airship captain Hans von Schiller

- Radio report on the disaster by Herbert Morrison (English); as MP3 (02:38 min., 2.42 MB) ( Memento from May 16, 2013 in the Internet Archive )

- Video: "Hindenburg Disaster Real Footage (1937)"

- Video: LZ 129 "Hindenburg" . Institute for Scientific Film (IWF) 1959, made available by the Technical Information Library (TIB), doi : 10.3203 / IWF / G-41 .

Individual evidence

- ^ Zeppelin Museum in Friedrichshafen , lustaufnatour.de, October 25, 2014, accessed on August 26, 2020.

- ↑ Hell rides: Titanic of the skies - The last ride of the Hindenburg , 12:16.

- ↑ Gudrun Ritscher: Working on an airship: The crews of the passenger airships LZ 127 "Graf Zeppelin" and LZ 129 "Hindenburg". In: Scientific yearbook of the Zeppelin Museum Friedrichshafen, Gessler, Friedrichshafen 2005, without ISBN, p. 79.

- ^ The Hindenburg - Triumph and Catastrophe in New York ( Memento from May 1, 2019 in the Internet Archive ), newyorkaktuell.nyc.

- ^ Peter Meyer: Airships. The history of the German zeppelins. Wehr & Wissen, Koblenz / Bonn 1980, ISBN 3-8033-0302-8 , p. 157.

- ^ Helmut Hütten: Motors. Technology, practice, history , 4th edition, Motorbuch Verlag, Stuttgart 1978, ISBN 3-87943-326-7 , p. 208.

- ^ Fritz Sturm: Propulsion system for the Zeppelin airship "LZ 129" , VDI magazine Volume 80, No. 13, March 28, 1936, p. 394 ( p. 393 at Google Books ).

- ↑ Lutz Tittel (Ed.): 1936–1937 LZ 129 “Hindenburg / 1937–1987 50 years of the Lakehurst misfortune” in “Writings on the history of the Zeppelin airship No. 5”. Gessler, Friedrichshafen 1987, ISBN 3-926162-55-4 , p. 23.

- ^ Gudrun Ritscher: Working on an airship: the crews of the passenger airships LZ 127 "Graf Zeppelin" and LZ 129 "Hindenburg". In: Scientific Yearbook of the Zeppelin Museum Friedrichshafen, Gessler, Friedrichshafen 2005, without ISBN, p. 81.

- ^ Peter Meyer: Airships. The history of the German zeppelins. Wehr & Wissen, Koblenz / Bonn 1980, ISBN 3-8033-0302-8 , p. 13.

- ↑ a b Alexander Michel: A giant makes the dust. , suedkurier.de , March 2, 2016.

- ↑ Lutz Tittel (Ed.): 1936–1937 LZ 129 “Hindenburg / 1937–1987 50 years of the misfortune of Lakehurst. In: Writings on the history of the Zeppelin airship, No. 5. Gessler, Friedrichshafen 1987, ISBN 3-926162-55-4 , p. 33.

- ↑ Frederick Birchall: 100,000 Hail Hitler; US Athletes Avoid Nazi Salute to Him. In: The New York Times , August 1, 1936, p. 1.

- ^ John Provan: The 'millionaires flight' - 1936. In: Airship (No. 140, June 2003), p. 26 ff.

- ↑ a b The last stop of LZ 129 "Hindenburg" in Europe , luftfahrtarchiv-koeln.de.

- ↑ Zeppelin Explodes Scores Dead in the US newsreel Universal Newsreel from May 10, 1937 (from 0:38).

- ↑ a b Michael Ossenkopp, Ulrich Zander, Alexander Michel: The Hindenburg disaster: When the airship burned up over 80 years ago , suedkurier.de, May 5, 2017.

- ^ Johann Althaus: "Hindenburg" crash, a sequence of fatal physics chains. welt.de , May 6, 2017, accessed on March 21, 2018.

- ↑ “No, gentlemen, that's nothin '” , spiegel.de , May 11, 1987.

- ^ Memorial to the Hindenburg airship accident in Lakehurst (USA) on May 6th, 1937. frankfurter-hauptfriedhof.de, accessed on November 11, 2019 .

- ↑ Bettina Erche: Frankfurt main cemetery . Supplementary volume on the monument topography of the city of Frankfurt am Main. Henrich, Frankfurt am Main 1999, ISBN 3-921606-35-7 , p. 424 .

- ↑ In 1937 the German airship journey died in America ( Memento from February 13, 2012 in the Internet Archive ), traunsteiner-tagblatt.de , 24/2007.

- ↑ Patrick Russell: Captain Ernst A. Lehmann. facesofthehindenburg.blogspot.com, October 5, 2009, accessed on November 11, 2019 .

- ^ David Grossman: Werner Franz, last surviving Hindenburg crew member, has died. , airship.net, August 28, 2014, accessed August 29, 2014.

- ↑ Sophie pipe Meier: farewell of a witness , abendblatt.de , August 29, 2014.

- ↑ Werner G. Doehner, Last Survivor of the Hindenburg, Dies at 90 , nytimes.com , November 16, 2019.

- ↑ Lutz Tittel (Ed.): 1936–1937 LZ 129 “Hindenburg / 1937–1987 50 years of the Lakehurst misfortune” (= writings on the history of Zeppelin aviation . No. 5 ). Gessler, Friedrichshafen 1987, ISBN 3-926162-55-4 , pp. 53 ff .

- ^ Report of the German committee of inquiry (1937) (see also two sketches from the report at the end of the following article ).

- ↑ radio report on the disaster by Herbert Morrison (English); as MP3 (02:38 min., 2.42 MB) ( Memento from May 16, 2013 in the Internet Archive ).

- ↑ Michael Rasch: Hindenburg-Omen point to the end of the share rally , nzz.ch , September 29, 2014.

- ↑ LZ 129 Hindenburg, ship description , July 13, 1936, p. 76.