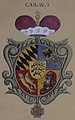

Coat of arms of Württemberg

The Coat of arms of Württemberg was until 1806 in the first place, the identification of members of the ruling family . Only after the elevation of Württemberg to a kingdom was a distinction made between the state coat of arms and the personal coat of arms of the royal family. Over time, the coat of arms went through many changes; these reflected territorial growth, changes in the rank of rulers or changes in the form of government.

Even if the existence of the state of Württemberg ended in 1945 and it was incorporated into Baden-Württemberg in 1952 , the various coats of arms of Württemberg can still be seen in many public buildings. The most famous of them are likely to be the coat of arms of Württemberg, the two coats of arms of the duchy between 1495 and 1789 and the coat of arms of the Kingdom of Württemberg .

Coat of arms of the Counts of Württemberg (until 1495)

Deer rod coat of arms

Until the end of the 12th century, there is little news about the Wuerttemberg family. The first known seal impression is from Count Konrad I. von (Württemberg-) Grüningen, who sealed a donation in Accon with it in 1228. It already shows the family coat of arms of the House of Württemberg: three deer poles lying on top of each other. It is believed that a line of Württembergians took over the coat of arms from the coat of arms of the Counts of Veringen at the end of the 12th century , after Count Hartmann of Württemberg , the alleged father of Konrad, married their heir. But it is also conceivable that Konrad took over the coat of arms in the course of his name change from Württemberg to Grüningen.

According to the report in the Clipearius Teutonicorum in the middle of the 13th century, both families carried the deer sticks in black on a yellow shield. The coat of arms of the Württembergers also appears in this form in the Zurich coat of arms roll around 1330, while the Veringian stag sticks are now red. The two Württemberg lines, which were formed as a result of Hartmann's succession, are distinguished in the Zurich coat of arms by their helmet decorations : The younger line shows a hunting horn, the older, later extinct Grüningen-Landau line a helmet with peacock feathers.

A seal as an "outlier"

A seal from 1238, which is known from a document that has only been received in copy and shows three towers on a mountain of three, does not fit into this picture. Because of the sparse tradition, its exact background remains in the dark; it is believed that it was taken over by Ludwig II , Hartmann's father, and the daughter of Count von Kirchberg as a result of the marriage . In any case, it seems to have only been in use for a short time, as no other records are known about it. Instead, the stag sticks developed into the Württemberg family coat of arms and were prominently represented in all subsequent changes in the coat of arms.

Seal of Count Ulrich I of Württemberg (1259)

Grave slab of Count Hartmann III. von Grüningen († 1280) in Markgröningen

Coat of arms of Count Ulrich III. with the imperial storm flag acquired together with Grüningen in 1336

Mömpelgard and the division of Württemberg in the 15th century

The first change to the coat of arms occurred in the middle of the 15th century, after Eberhard IV married Henriette von Mömpelgard in 1407 . Due to the female line of succession permitted there, after her death in 1444, Mömpelgard on the left bank of the Rhine fell to her son Ludwig I from the Urach line, which had recently split off from the Stuttgart line under Ulrich V. From this point on, the Counts of Urach had a four-quarter coat of arms, with the stag sticks in the 1st and 4th fields and the Mömpelgard coat of arms in the 2nd and 3rd fields, with two golden barbels turned away in red . The coat of arms of the Counts of Stuttgart did not change at first. It was not until the Urach Treaty of 1473 that both lines agreed to call themselves “Counts of Württemberg and Mömpelgard” and to carry the corresponding coat of arms.

Separate coats of arms Mömpelgard and Württemberg in the Ingeram Codex , 1459

Coat of arms of Count Ulrich V of Württemberg-Stuttgart in Waiblingen

Coat of arms of Count Eberhard V from 1491, also in Waiblingen

Coat of arms of the Dukes of Württemberg (1495 to 1803)

Four-part coat of arms (1495 to 1705)

At the Reichstag in Worms in 1495, Eberhard im Bart achieved the elevation of the now reunified county to the Duchy of Württemberg. On this occasion he adopted a new, quartered coat of arms, which showed the stag in the first field and the barbel in the fourth field. The second field was roughened diagonally of gold and black, which was the coat of arms of the extinct Dukes of Teck . The people of Württemberg had already acquired their regular property in the 14th century, which is why Emperor Maximilian Eberhard had given permission to use the title and coat of arms of a Duke of Teck. The Reichssturmfahne in the third field reminded us that the Wuerttemberg people held the office of Reich banner bearers. This (more symbolic) dignity, which was connected with the possession of Markgröningen , was Count Ulrich III. Awarded in 1336.

This escutcheon was valid for 210 years. In the full coat of arms, two helmet decorations were first placed on it, the red hunting horn that had already been used, and the tecksche helmet ornament, a gold-black roughened bracken body, which emphasized the two duke titles again. Eberhard im Bart added a palm tree and his motto “Attempto” ( I dare ) in his seal as a personal sign , which referred to his pilgrimage to Jerusalem . Eberhard's successors as dukes replaced them with their own additional symbols, but otherwise left the coat of arms unchanged.

When Duke Ulrich was expelled from his country in 1519, Austria took control. The Archduke Ferdinand , who was appointed governor, created a new coat of arms for this purpose. This was quartered, with all fields split again: in the 1st and 4th field the Austrian shield and the blue-yellow inclined beams from Burgundy , in the 2nd and 3rd field deer sticks and diamonds from Württemberg and Teck. A black eagle stood in the golden heart shield . T. again wore a breastplate with the coat of arms of Austria / Burgundy.

With the return of Duke Ulrich in 1534, this coat of arms disappeared. Ulrich only got his territory back in the Kaaden Treaty as an Austrian after-fief , and even when Duke Friedrich I bought the conversion of Württemberg back into an imperial fief in 1599, the Habsburgs were granted an entitlement to the land in the event that the House of Württemberg became a male line should die out. As a sign of this claim, the stag sticks continued to appear in the coat of arms of the Archdukes of Austria and even appeared in the great coat of arms of the Austrian Empire in 1804 . It was not until 1805 that the Peace of Pressburg ended Austrian claims.

Keystone of the Johanneskirche in Weinsberg from 1510

Coat of arms from Duke Ulrich's time at the Old Chancellery in Stuttgart

Austrian coat of arms in the Lorch monastery

The Württemberg-Mömpelgard line, whose area on the left bank of the Rhine had not been included in the duchy, initially carried on the old Count's coat of arms. However, when the Stuttgart line of the house died out and Friedrich I of the Mömpelgard line became duke in 1593, he took over the ducal coat of arms and added a third crest in the form of a red-clad woman's torso with two fish instead of the arms; this was the crest of the Counts of Mömpelgard. Several side lines of the house emerged among the descendants of Friedrich. Most of them carried the family coat of arms without any further distinguishing features, only the Württemberg-Oels sideline, created in 1648 by Duke Silvius Nimrod , supplemented it with a heart shield with the Silesian eagle.

Coat of arms of Frederick I in a coat of arms book showing the coats of arms of visitors to the Regensburg Reichstag from 1594

Coat of arms from the time of Duke Friedrich I on the old chancellery in Stuttgart

Coat of arms from 1621 on the church in Diefenbach

Four-part coat of arms with heart shield (1705 to 1789)

The next change in the escutcheon was made under Duke Eberhard Ludwig . The reason for this was a dispute over the office of the Reichsbannerträger, which Württemberg was contested by the Electors of Hanover (see also the Erzamt article ). After Württemberg had won the dispute, the coat of arms was changed in 1705. The original intention to emphasize the Reichssturmfahne more strongly, however, was given up. Instead, the stag sticks were placed in a heart shield, the other fields moved up, and in the fourth field was a red-clad man's head ("Heidenkopf"), the coat of arms of the town and rule of Heidenheim , which Württemberg had owned since 1536. The number of helmets was increased to five, so that now each field corresponded to a crest. Because of the complicated design, these crests were often left out and replaced by a ducal hat.

Coat of arms of Duke Eberhard Ludwig at the tube fountain in Feuchtwangen 1727

Depiction of the coat of arms of Duke Karl Alexander at the Marbach city gate

Coat of arms of Duke Carl Eugen at the Röhrbrunnen in Eberstadt

The change of coat of arms of 1789

Several territorial acquisitions by Duke Carl Eugen should lead to another change of coat of arms in 1789. First of all, the acquisition of the Justingen estate in 1751 brought additional voting rights in the Swabian district council and in the Swabian Counts College of the Reichstag . A part of the County of Limpurg acquired in 1780/82 brought membership in the Franconian Counts College, and in 1784/85 Carl Eugen bought the Bönnigheim estate . Two years later, the duke expressed the wish for the first time to perpetuate these increases in heraldry. The negotiations dragged on, however, and it was not until December 2, 1789 that the new coat of arms was established by ducal order. In it, Bönnigheim was not considered as a “mere city coat of arms”, instead the shield was divided and split twice with a heart shield. The new fields were: in blue a silver slanting thorn bar ( Justingen ) or quartered, in the 1st and 4th fields in red four silver tips, in the 2nd and 3rd fields in blue five (3: 2) silver maces (Limpurg) . The coat of arms was crowned by a total of seven helmets, one for each field, with corresponding helmet decorations, and for the first time the whole arrangement was set in a coat of arms.

Because of the known intention of the Duke to take the Bönnigheim coat of arms into account and the delay of several years until the new coat of arms was accepted, there was uncertainty about its actual design. Even before 1789, several princes of the house created new seals for themselves, and the royal iron foundries produced a.o. a. Well walls with different shield divisions, in which Bönnigheim also appeared. This state of affairs makes it understandable that this section of the Württemberg coat of arms is often misrepresented in half-timbered buildings.

Different representation in Maulbronn Monastery : Duke Ludwig Eugen , 1794

Electoral coat of arms (1803 to 1806)

Through the Reichsdeputationshauptschluss of 1803, Württemberg obtained the electoral dignity and considerable territorial growth. On this occasion, the coat of arms was extended again, whereby the now split heart shield with its front half (Reichssturmfahne) particularly emphasized the archbanner office associated with the electoral dignity . The prince provosty of Ellwangen (a golden inful in silver ), which indicated the seat of the New Württemberg government in Ellwangen, was added to the new fields , as well as the former imperial city of Hall , which had a large territory (divided, above in red a golden cross, below in gold a silver oath hand), an imperial eagle for the other annexed imperial cities and a blank " waiting sign ", which reflected the hope of further territorial gains. It is noteworthy that the Mömpelgarder barbs were still represented in the coat of arms, although the county had been annexed by France; the two fish were now interpreted as a speaking symbol for the imperial abbey of Zwiefalten , which fell to Württemberg . The helmet decorations were all gone, the shield was only in a coat of arms with an elector's crown.

Because of the small and complex design of this coat of arms, only its heart shield was sometimes shown, e.g. B. above the portal of the Prinzenbau at today's Stuttgart Schillerplatz . Badges of possession, which were nailed to public buildings in the newly acquired areas, had the simple form, like the one shown here that was unauthorizedly affixed in the Principality of Hohenzollern.

Heart sign at the Prinzenbau in Stuttgart

Coat of arms of the Kingdom of Württemberg (1806 to 1918)

The coat of arms from 1806 to 1817

In the Peace of Pressburg, which was concluded at the end of 1805 , Wuerttemberg received Upper Austrian territories in Upper Swabia and was elevated to a kingdom, initially without leaving the Holy Roman Empire . (This step only took place six months later with the establishment of the Rhine Confederation .) The acceptance of the royal dignity by Frederick I was officially announced on January 1st, 1806. With this increase in rank (as expected) a new coat of arms was due again. which, however, was a national coat of arms in contrast to earlier - as a personal coat of arms, Friedrich kept the electoral coat of arms with the (Latin) inscription "Friedrich by God's grace, King of Württemberg".

The most important changes to the escutcheon were the addition of two fields and the change of the heart shield. The new fields did not represent the newly acquired areas, but took up old, long-extinguished titles. In the split and crowned heart shield there were now three lions next to the stag sticks, the coat of arms of the Hohenstaufen dynasty , who had been dukes of Swabia until they died out in the 13th century . With this symbolism King Friedrich made his claim to the succession of the Hohenstaufen as ruler of Swabia clear; he initially called himself “Prince of Swabia”, later “sovereign Duke in Swabia” and hoped (ultimately in vain) to be able to expand his empire to the extent of the old duchy in the foreseeable next round of mediatization . H. including bathing , parts of Switzerland and the areas up to the Lech . The coat of arms of the Count Palatine of Tübingen was added prominently in the first row of the main shield (a red church flag in gold), although their areas had belonged to Württemberg since the 14th century and were included in the old duchy; this corresponded to the title of "Landgrave of Tübingen", which Friedrich had accepted in 1803.

For the first time, shield holders appeared in this coat of arms , namely a black lion and a golden stag corresponding to the heart shield, both of which also held an imperial storm flag as a sign of the archbanner office (which was still claimed at that time). In connection with this, Friedrich still uses the sub-title Graf zu Gröningen . The coat of arms was now completed with a royal crown.

With this coat of arms the climax of the variety of forms in the history of the Württemberg coat of arms was reached. As before, it was often reduced to the heart shield in depictions, e.g. B. in the publisher's vignette of the court and office printer Cotta . The territorial expansions of 1806 and 1810 that followed soon after were not reflected in the state heraldry.

The coat of arms from 1817

While the coat of arms became more extensive with every change in history, it was first reduced in 1817. Frederick's successor as king, Wilhelm I , not only reduced his title to that of "King of Württemberg", but with a decree of December 30, 1817 also the coat of arms, which was essentially reduced to the previous heart shield. The decree stipulated an oval shield, wrapped in a golden oak wreath, on which a helmet and a crown sat as a larger coat of arms; the shield holders remained in place (without the Reichssturmfahne) and now stood on a red and black ribbon with a golden inscription "Feartlos und trew". In the smaller coat of arms, the shield holder, banner and helmet were omitted, and the shield was wreathed with a laurel and palm branch.

The colors of the banner also corresponded to the national colors black and red, which had been introduced a year earlier by decree of December 26, 1816. They replaced the colors black-red-gold, which were only introduced on December 14, 1809, by which the house colors that had been in effect since Duke Friedrich I , the Mömpelgarder red-gold, had been supplemented by the black of the stag sticks; this change was not least due to the fact that tricolors had become popular during the domination of France . After the Wars of Liberation , the associated revolutionary symbolism was frowned upon; however, red and yellow were now the state colors of the new neighbor Baden, and black and yellow were the Habsburg colors, so that the only two-color combination that remained was black and red.

In Thouret's draft coat of arms, the right front paw of the lion holding the shield was colored red, later this was partially transferred to the front paws of the lions in the shield (e.g. in Siebmacher's book of arms). This was explained with a legend that the Hohenstaufen lions were originally red and only turned black after the execution of Konradin , the last Hohenstaufen, which is proven not to be true. By the end of the 19th century at the latest, the front paws were uniformly tinged in black .

The design of the coat of arms, in which two golden halves of the shield met, was often criticized by heraldists, so that there was no lack of alternative suggestions over time. Ultimately, however, it remained unchanged until the end of the kingdom.

Smaller coat of arms at Maulbronn District Court

Coat of arms of the state of Württemberg after 1918

In November 1918, King Wilhelm II abdicated and the Free People's State of Württemberg was proclaimed. The changed circumstances were taken into account with a new coat of arms, which the state parliament passed on December 20, 1921. The law regarding the colors and coat of arms of Württemberg came into force on February 20, 1922 and laid down a four-quarter coat of arms, whereby fields 1 and 4 were gold with three black stag poles, while fields 2 and 3 were divided three times by black and red Two golden stags acted as shield holders, and instead of royal insignia, the coat of arms was elevated by a “people's crown”, which symbolized the basic democratic order after the end of the monarchy. An announcement by the State Ministry on the same date determined a template for the official use of the coat of arms. Ministries and the highest state authorities should use the full coat of arms in their seals, all other authorities should only use the coat of arms.

The design of the coat of arms was guided by the desire to ensure that the national colors of black and red were retained in the coat of arms. The quarter prevailed over a design in which the stag sticks (in gold) were to be placed in a black and red shield, but was exposed to criticism, both for heraldic and artistic reasons (small-scale design) and for political ( Rejection of a new coat of arms or the new form of government per se in conservative circles). The coat of arms therefore only found a majority of 38:26 votes in the state parliament.

The takeover of power by the National Socialists and the subsequent synchronization of the state governments did not remain without effects on the Württemberg coat of arms. By law and notice of August 11, 1933, details of the coat of arms were changed and a new template was established. While the coat of arms itself remained unchanged, the people's crown was omitted and the shield bearers now stood on a banner with the old motto “Fearless and trew”.

After the Second World War , Württemberg was divided along the border by the American and French occupation zones; the states of Württemberg-Baden and Württemberg-Hohenzollern were created , which merged to form Baden-Württemberg in 1952, including Baden . The Württemberg coat of arms remained in use for Württemberg-Hohenzollern, while Württemberg-Baden created a new coat of arms, which took over the stag sticks and a pair of black and red stripes.

Württemberg traces in today's coat of arms

The new federal state of Baden-Wuerttemberg used the Hohenstaufen lions in its choice of coat of arms . Although these had already appeared in the Württemberg royal coat of arms, they were considered suitable to represent the whole of Baden-Württemberg, since the Hohenstaufen as dukes of Swabia had once ruled over most of the state. In the large coat of arms of the state, a deer serves as a shield holder, and one of the plaques in the turtle shows the coat of arms of Württemberg with the three stag sticks.

In local heraldry, Hirschstangen often reminds of the former affiliation of municipalities and districts to Württemberg (see in detail the article Hirschstangen ). The former extension of Württemberg rule is also documented in the coats of arms of the Alsatian communities Andolsheim and Riquewihr (Reichenweier), the city of Montbéliard (Mömpelgard) in Franche-Comté and the Upper Silesian community Pokój (Carlsruhe O / S). The coats of arms of the cities of Freudenstadt and Ludwigsburg , which emerged as new ducal foundations in the 17th and 18th centuries, are completely or partially taken from the ducal coats of arms: Freudenstadt shows the Mömpelgardian barbel, Ludwigsburg the imperial storm flag acquired in 1336 with the County of Grüningen .

The coat of arms of the automobile manufacturer Porsche , which connects the state coat of arms valid after 1922 with the city coat of arms of the company headquarters in Stuttgart and has been in use since 1953 , is known worldwide . The stag sticks in the VfB Stuttgart logo are an example of the use of Württemberg symbolism by sports clubs .

Coat of arms of the city of Ludwigsburg with the imperial storm flag from Grüningen

Porsche logo with stag sticks and colors of Württemberg and the Stuttgart Rössle in the heart shield

Emblem of VfB Stuttgart with three abstract stag sticks

Further information

See also

literature

- Adam, AE: The ducal-Württemberg coat of arms since the acquisition of Bönnigheim . In: Württembergische Vierteljahreshefte, NF 1 (1892), pp. 80–85

- Alberti, Otto von: Wuerttemberg Nobility and Arms Book. Booklet 1. History of the Württemberg coat of arms . Kohlhammer, Stuttgart, 1889 ( digitized version )

- Graser, Gerhard: The Reichssturmfahne . In: Hie gut Württemberg, 2nd year, Ludwigsburg 1951, pp. 81–82.

- Heyd, Ludwig Friedrich : History of the Counts of Gröningen . 106 pp., Stuttgart 1829.

- Heyd, Ludwig Friedrich: History of the former Oberamts-Stadt Markgröningen with special consideration for the general history of Württemberg, mostly based on unpublished sources . Stuttgart 1829, 268 p., Facsimile edition for the Heyd anniversary, Markgröningen 1992.

- Schukraft, Harald : A short history of the House of Württemberg . Silberburg-Verlag, Tübingen 2006, ISBN 978-3-87407-725-5 .

- Steinbruch, Karl-Heinz: On the history of the state heraldry of the predecessor territories of the states of the Federal Republic of Germany. Part 1: Baden-Württemberg and Bavaria . In: Herold-Jahrbuch, NF 7 (2002), pp. 189–205.

- Titan von Hefner, Otto: Siebmachersches Großes und Allgemeines Wappenbuch, Volume 1: The coats of arms and flags of the rulers and states of the world . Nuremberg 1856.

- Unknown: Bönnigheim and the Württemberg coat of arms . In: Ganerbe Blätter, Volume 9, pp. 34–39, Bönnigheim 1986.

Footnotes

- ↑ According to Crusius (Heyd, Ludwig Friedrich: History of the former Oberamts-Stadt Markgröningen with special consideration for the general history of Württemberg, mostly based on unprinted sources . Stuttgart 1829, 268 p., Facsimile edition for the Heyd anniversary, Markgröningen 1992, p. 9 ): "Anitzo, the parish priest, lives in the castle where the old counts once resided."

- ↑ The first heraldic evidence of the Kirchbergers is a seal around 1200, which shows three covered towers. See also Schukraft, Harald: Brief history of the House of Württemberg . Silberburg-Verlag, Tübingen 2006, ISBN 978-3-87407-725-5 , p. 15.

- ↑ Three Count Hartmann von Grüningen can be proven on the basis of the documents and registers that have been handed down. Two transition phases of the generation change can be identified from the occasional use of the nickname senior . A fourth Hartmann ( dictus de Grüningen ) is also mentioned once in 1284 .

- ↑ Reports according to which a new coat of arms including Bönnigheim was adopted as early as 1785, go back to an error Lebret from 1818, which was refuted by Alberti and Adam. Siebmacher's coat of arms book even dates the adoption of the coat of arms to Duke Karl Alexander in 1736, but this cannot be correct because the areas in question were not yet part of Württemberg at that time.

- ↑ This subheading refutes the thesis that the Counts of Grüningen named themselves after Grüningen near Riedlingen. See quote from Baden-Württemberg State Bibliography (BSZ)

- ↑ Reyscher, Collection of Württemberg Laws , Volume III, page 501

- ↑ The first mention of the color black is known from Konrad von Mure in 1265, three years before Konradin's death.

- ↑ Ströhl called it in his German coat of arms roll from 1897 - often quoted - "an excellent example of how not to tear open a coat of arms."

- ↑ Law on colors and coats of arms of Württemberg of February 20, 1922 (RegBl 1922, page 105)

- ↑ see the negotiations of the Landtag of the Free People's State of Württemberg , pages 2622/2651 as well as appendices 356 and 600

- ↑ Law of the State Ministry on the coat of arms of Württemberg of August 11, 1933 (RegBl 1933, page 337)

- ↑ Information on automobile manufacturers' marks

Web links

- Zurich coat of arms roll ( Memento from August 18, 2012 in the Internet Archive )