Holy Roman Empire

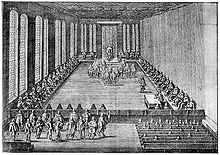

In the center is Emperor Ferdinand III. depicted as the head of the empire in the circle of the electors . A woman sits at his feet as an allegory of the empire, recognizable by the insignia of the imperial apple . The surrounding fruits symbolize the hope for new prosperity after the end of the Thirty Years' War .

The original is signed with: Germany's happy shouting / to blissful continuation / the general assembly of H. Röm, which was organized with God / in Regensburg. Rich supreme head and limbs

Holy Roman Empire ( Latin Sacrum Imperium Romanum or Sacrum Romanum Imperium ) was the official name for the domain of the Roman-German emperors from the late Middle Ages to 1806. The name of the empire is derived from the claim of the medieval Roman-German rulers, the tradition of the ancient To continue the Roman Empire and to legitimize the rule as God's holy will in the Christian sense.

The empire was formed in the 10th century under the Ottonian dynasty from the former Carolingian eastern France . With Otto I's coronation as emperor on February 2, 962 in Rome, the Roman-German rulers (like the Carolingians before) followed up on the idea of the renewed Roman Empire, which was at least in principle adhered to until the end of the empire. The area of Eastern Franconia was first referred to in the sources as Regnum Teutonicum or Regnum Teutonicorum ("Kingdom of the Germans ") in the 11th century ; but it was not the official title of the Reich. The name Sacrum Imperium is first documented for 1157 and the title Sacrum Romanum Imperium for 1184 (older research was based on 1254). The addition of German nation ( Latin Nationis Germanicæ ) was occasionally used from the late 15th century. Due to its pre-national and supranational character of a multi-ethnic empire with universal claims, the empire never developed into a nation- state or a state of modern character, but remained a monarchically- led, estates -based structure of emperors and imperial estates with only a few common imperial institutions.

In contrast to the German Empire , which was founded in 1871 , it is also known as the Roman-German Empire or the Old Empire .

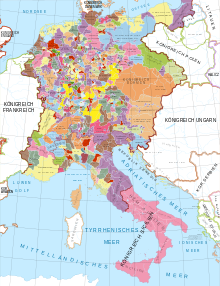

The expanse and borders of the Holy Roman Empire changed significantly over the centuries. In its greatest expansion, the empire encompassed almost the entire area of what is now central and parts of southern Europe . Since the early 11th century it consisted of three parts of the empire: the north Alpine (German) part of the empire , imperial Italy and - until it was actually lost at the end of the late Middle Ages - Burgundy (also known as Arelat ).

Since the early modern period , the empire was structurally incapable of offensive warfare, expansion of power and expansion. Since then, legal protection and peacekeeping have been seen as its main purposes. The empire should ensure calm, stability and the peaceful resolution of conflicts by curbing the dynamics of power: it should protect subjects from the arbitrariness of the sovereigns and smaller imperial estates from violations of the rights of more powerful estates and the emperor. Since neighboring states had also been integrated into its constitutional order as imperial estates since the Peace of Westphalia of 1648, the empire also fulfilled a peacekeeping function in the system of European powers.

Since the middle of the 18th century, the empire has been able to protect its members less and less against the expansive policies of internal and external powers. This contributed significantly to his downfall. Due to the Napoleonic Wars and the resulting founding of the Rhine Confederation , whose members left the empire, it was almost incapable of acting. The Holy Roman Empire expired on August 6, 1806 with the laying down of the imperial crown by Emperor Franz II.

character

The Holy Roman Empire emerged from the East Franconian Empire . It was a pre- and national entity, a Lehnsreich and persons member State who has never become a nation-state such as France or the UK developed and from the history of ideas would be never understood reasons as such. The competing contrast of consciousness in the tribal duchies or later in the territories and the supranational consciousness of unity was never carried out or dissolved in the Holy Roman Empire, an overarching national feeling did not develop.

The history of the empire was shaped by the dispute over its character, which - since the power relations within the empire were by no means static - changed again and again over the centuries. From the 12th and 13th centuries, a reflection on the political community can be observed, which is increasingly oriented towards abstract categories. With the rise of universities and an increasing number of trained lawyers, the categories of monarchy and aristocracy, taken from the ancient theory of the forms of the state, have been juxtaposed here for several centuries . However, the empire could never be clearly assigned to one of the two categories, since the power of government of the empire was neither in the hands of the emperor nor in the hands of the electors or in the entirety of an association such as the Reichstag . Rather, the empire combined features of both forms of government. Thus came in the 17th century Samuel Pufendorf in his published under a pseudonym magazine De statu imperii to the conclusion that the kingdom of its own kind is - a "irregular and more like a monster body" (irregular aliquod corpus et monstro simile) what Karl Otmar von Aretin is referred to as the most frequently cited sentence on the imperial constitution from 1648 onwards.

As early as the 16th century, the concept of sovereignty moved more and more into focus. The distinction between the federal state (in which the sovereignty lies with the entire state) and the state federation (which is a federation of sovereign states) is based on this, however, is an ahistorical approach, since the fixed meaning of these categories only emerged later. It is also not informative with regard to the empire, since the empire again could not be assigned to either of the two categories: just as the emperor never succeeded in breaking the regional idiosyncrasy of the territories, it has broken up into a loose confederation of states. More recent research emphasizes the role of rituals and the staging of rule in premodern society, especially with regard to the unwritten hierarchy and constitutional order of the empire until its dissolution in 1806 ( symbolic communication ).

As an “umbrella organization”, the empire overran many territories and gave the coexistence of the various sovereigns the framework conditions prescribed by imperial law. These quasi-independent, but not sovereign princes and duchies recognized the emperor as at least the ideal head of the empire and were subject to imperial laws, imperial jurisdiction and the resolutions of the Reichstag, but at the same time also through the election of a king , electoral surrender , Reichstag and other estates in imperial politics involved and could influence them for themselves. In contrast to other countries, the residents were not directly subject to the emperor, but to the sovereign of the respective imperial territory. In the case of the imperial cities, this was the city's magistrate .

Voltaire described the discrepancy between the name of the empire and its ethno- political reality in its later phase (since the early modern period ) with the sentence: “This corpus, which is still called the Holy Roman Empire, is in no way sacred, nor Roman , another empire. ” Montesquieu described the empire in his 1748 work Vom Geist deretze as “ république fédérative d'Allemagne ” , as a federally structured polity in Germany.

In recent research, the positive aspects of the empire are again emphasized, which not only offered a functioning political framework for several centuries, but also (precisely because of the more federal rulership structure) allowed diverse developments in the various domains.

Surname

The name raised the claim to the succession of the ancient Roman Empire and thus to universal rule. At the same time there was fear of the coming true of the prophecies of the prophet Daniel , who had predicted that there would be four world empires and afterwards the Antichrist would come to earth ( doctrine of the four kingdoms ) - the apocalypse was about to begin. Since the (ancient) Roman Empire was counted as the fourth empire in the doctrine of the four kingdoms , it was not allowed to perish. The increase with the addition "Holy" emphasized the divine right of the Empire and the legitimation of rule through divine law .

With the coronation of the Frankish king Charlemagne as emperor by Pope Leo III. in the year 800 he placed his empire in the succession of the ancient Roman empire , the so-called Translatio Imperii . Historically and according to its own self-image, however, there was already an empire that arose out of the old Roman Empire, namely the Christian-Orthodox Byzantine Empire ; According to the Byzantines, the new Western “Roman Empire” was a self-proclaimed and illegitimate one.

At the time of its formation in the middle of the 10th century, the empire did not yet have the title holy. The first Emperor Otto I and his successors saw themselves as God's representatives on earth and were thus seen as the first protector of the church. So there was no need to emphasize the sanctity of the kingdom. The empire was still called Regnum Francorum orientalium or Regnum Francorum for short .

In the imperial titulatures of the Ottonians, however, the name components that were later transferred to the entire empire appear. In the documents of Otto II from the year 982, which arose during his Italian campaign, the title Romanorum imperator Augustus, "Emperor of the Romans" can be found. Otto III. rose above all spiritual and worldly powers in his title by humbly calling himself “servant of Jesus Christ” ( servus Jesus Christ ) and later even “servant of the apostles” ( servus apostolorum ) , analogous to the pope and thus rising above him .

This sacred charisma of the empire was massively attacked by the papacy in the investiture dispute from 1075 to 1122 and ultimately largely destroyed. The canonization of Charlemagne in 1165 and the concept of the sacrum imperium , which was first attested in 1157 in Frederick I's chancellery , were interpreted in research as an attempt "to separate the empire from the church through its own sanctity and to contrast it as equivalent" . According to this, holiness is a "process of secularization". However, Frederick never referred to his holy predecessor Karl, and the sacrum imperium did not become an official language in Frederick's time.

Regnum Teutonicum or Regnum Teutonicorum appear as a self-name in the sources for the first time in the 1070s. The terms were already used in Italian sources at the beginning of the 11th century, but not by authors in Imperial Italy . It was also not an official imperial title, which is why it was generally not used in the chancellery of the medieval Roman-German kings. The title rex Teutonicus was deliberately used by the papacy in order to indirectly dispute or relativize the universal claim of the rex Romanorum to rule rights outside the German part of the empire (as in the Arelat and in imperial Italy). In the papal chancellery language, a title was deliberately used during the investiture controversy that the Roman-German kings themselves did not use. Later, terms like regnum Teutonicum continued to be used as "battle terms " to contest claims to power by the Roman-German kings, such as in the 12th century by John of Salisbury . The Roman-German kings, on the other hand, insisted on their titulature rex Romanorum and on the designation of the empire as Romanum Imperium .

In the so-called Interregnum from 1250 to 1273, when none of the three elected kings succeeded in asserting themselves against the others, the claim to be the successor to the Roman Empire was combined with the predicate sacred to denote Sacrum Romanum Imperium (German "Heiliges Römisches Rich"). The Latin phrase Sacrum Romanum Imperium was first recorded in 1184 and became the common imperial title from 1254; it appeared in German-language documents around a hundred years later since the time of Emperor Charles IV . In the late Middle Ages, the universal claim of the empire was still adhered to. This was true not only for the period of the so-called interregnum, but also for the 14th century, when tensions and open conflicts with the papal curia arose again during the reigns of Henry VII and Louis IV . The formulation Imperium Sanctum is already occasionally documented in the late ancient Roman Empire.

The addition Nationis Germanicæ only appeared on the threshold between the late Middle Ages and the early modern period , when the empire essentially extended to the area of the German-speaking area. In 1486 this title was included in the Landfriedensgesetz of Emperor Frederick III. used. This addition was officially used for the first time in 1512 in the preamble to the farewell to the Reichstag in Cologne. Emperor Maximilian I had invited the imperial estates among other things for the purpose of preserving [...] the Holy Roman Empire of the Teutsche Nation . The exact original meaning of the addition is not entirely clear. A territorial restriction can be meant after the emperor's influence in imperial Italy had sunk to a de facto zero point and large parts of the kingdom of Burgundy were now ruled by France. On the other hand, there is also an emphasis on the sponsorship of the empire by the German imperial estates , which was supposed to defend their claim to the imperial idea . Towards the end of the 16th century, the formulation disappeared from official use again, but was still used occasionally in literature until the end of the empire.

The Latin word natio did not have a completely uniform meaning until the 18th century; the intended community of origin could sometimes be narrower, sometimes wider than the “people” in today's sense. The addition of “German nation” does not make the Holy Roman Empire the nation state as we know it.

Until 1806, the Holy Roman Empire was the official name of the empire, often used as SRI for Sacrum Romanum Imperium in Latin or H. Röm. Rich or similar was abbreviated in German. In addition, terms such as German or Teutsches Reich and Teutsch- or Germany are used in modern times . It was not until the Reichsdeputationshauptschluss of 1803, the Rheinbund act as well as the declaration of dissolution of Emperor Franz II. From 1806 officially use the German or Teutsches Reich and Teutschland for the Holy Roman Empire.

Shortly after its dissolution, the Holy Roman Empire was increasingly given the addition of German nation in historical treatises , and so in the 19th and 20th centuries this originally only temporary designation was not quite correctly established as the general name of the empire. It is also called the Old Reich to distinguish it from the later German Empire from 1871 onwards.

story

Emergence

The Frankish Empire had several divisions and reunions of parts of the empire through after the death of Charlemagne 814 among his grandchildren. Such divisions among the sons of a ruler were normal under Frankish law and did not mean that the unity of the empire ceased to exist, since a common policy of the parts of the empire and a future reunification were still possible. If one of the heirs died childless, his part of the empire fell to one of his brothers or was divided among them.

Such a division was also decided in the Treaty of Verdun in 843 among the grandsons of Charles. The empire was divided between Charles the Bald , who received the western part ( Neustria , Aquitaine ) up to around the Meuse , and Lothar I - he took over a central strip (with a large part of Austrasia and the formerly Burgundian and Longobard regions up to around Rome) the imperial dignity - and Ludwig the German , who received the eastern part of the empire with part of Austrasia and the conquered Germanic empires north of the Alps.

Although the future map of Europe is not recognizable here, not intended by those involved, in the course of the next fifty years there were further, mostly warlike, reunions and divisions between the sub-kingdoms. Only when Charlemagne was deposed in 887 because of his failure to defend himself against the plundering and robbing Normans , a new head of all parts of the empire was no longer appointed, but the remaining partial empires chose their own kings, some of which no longer belonged to the Carolingian dynasty . This was a clear sign of the fact that the parts of the empire were drifting apart and that the reputation of the Carolingian dynasty, which had reached its low point, plunged the empire into civil wars through disputes over the throne and was no longer able to protect it as a whole against external threats. As a result of the lack of dynastic brackets, the empire split up into numerous small counties, duchies and other regional lordships, most of which only formally recognized the regional kings as sovereignty.

In 888, the central part of the empire was particularly clearly divided into several independent small kingdoms, including Upper Burgundy and Lower Burgundy and Italy (while Lorraine was annexed to the Eastern Empire as a lower kingdom), whose kings had prevailed against Carolingian pretenders with the support of local nobles. In the Eastern Empire, the local nobles elected dukes at the tribal level. After the death of Ludwig the child , the last Carolingian on the East Franconian throne, the Eastern Empire could also have broken up into small empires if this process had not been stopped by the joint election of Konrad I as King of Eastern Franconia. Although Konrad did not belong to the Carolingian dynasty, he was a Franconian from the Conradin dynasty . On this occasion, however, Lorraine joined Western France. In 919, Heinrich I , Duke of Saxony, was the first non-Franconian elected King of Eastern Franconia in Fritzlar . From that point on, the empire was no longer ruled by a single dynasty, but the regional greats, nobles and dukes decided who ruled.

In the year 921 the West Franconian ruler recognized Heinrich I as having equal rights in the Treaty of Bonn ; he was allowed to use the title rex francorum orientalium, King of the Eastern Franks. The development of the empire as a permanently independent and viable state was thus essentially complete. In 925 Heinrich succeeded in reintegrating Lorraine into the East Franconian Empire.

Despite the detachment from the overall empire and the unification of the Germanic peoples who, in contrast to the common people of Western Franconia, did not speak Romanized Latin, but theodiscus or diutisk (from diot popularly, vernacular), this empire was not an early " German nation-state ". There was no overriding “national” sense of belonging in Eastern Franconia anyway, and the imperial and linguistic communities were not identical. Neither was it the later Holy Roman Empire.

The increasing self-confidence of the new East Franconian royal family was already evident in the accession to the throne of Otto I , son of Henry I, who was crowned on the supposed throne of Charlemagne in Aachen . Here the increasingly sacred character of his rule was shown by the fact that he allowed himself to be anointed and vowed his protection to the church. After several battles against relatives and dukes of Lorraine, he succeeded in defeating the Hungarians in 955 on the Lechfeld near Augsburg, confirming and consolidating his rule. According to Widukind von Corvey, the army is said to have greeted him as emperor while still on the battlefield .

This victory over the Hungarians prompted Pope John XII. To call Otto to Rome and offer him the imperial crown so that he could act as the protector of the church. At this time Johannes was under the threat of regional Italian kings and hoped Otto would help against them. But the Pope's cry for help also shows that the former barbarians had turned into the bearers of Roman culture and that the eastern regnum was seen as the legitimate successor to the empire of Charlemagne. Otto followed the call and moved to Rome. There he was crowned emperor on February 2, 962. West and East Franconia finally developed politically into separate empires.

middle age

Rule of the Ottonians

In the early Middle Ages, the empire was still little differentiated classically and socially in comparison to the High and Late Middle Ages . It was visible in the army, in the local court assemblies and in the counties , the local administrative units already installed by the Franks. The highest representative of the political order of the empire, responsible for the protection of the empire and peace within, was the king. The duchies served as political sub-units . Until the late Middle Ages, the consensus between the rulers and the greats of the empire ( consensual rule ) was important.

Although in the early Carolingian period around 750 the Franconian official dukes were deposed for the peoples who were subjugated by the Franks or who only emerged from their territorial consolidation, in the East Franconian Empire, aided by the external threat and the preserved tribal law, five new ones emerged between 880 and 925 Duchies: that of the Saxons , the Bavarians , the Alemanni , the Franks and the newly created Duchy of Lorraine after the division of the empire , to which the Frisians also belonged. But already in the 10th century there were serious changes in the structure of the duchies: Lorraine was divided into Lower and Upper Lorraine in 959 and Carinthia became an independent duchy in 976.

Since the empire emerged as an instrument of the self-confident duchies, it was no longer divided between the ruler's sons and also remained an elective monarchy . The non-sharing of the “inheritance” between the king's sons contradicted traditional Franconian law, but on the other hand the kings ruled the tribal dukes only as liege lords. The direct influence of the kingship was correspondingly small. In 929 Heinrich I laid down in his " House Rules " that only one son should succeed on the throne. Already here the concept of inheritance, which shaped the empire up to the end of the Salier dynasty, and the principle of the elective monarchy are connected with one another.

As a result of several campaigns in Italy, Otto I (r. 936–973) succeeded in conquering the northern part of the peninsula and integrating the kingdom of the Lombards into the empire. A complete integration of imperial Italy with its superior economic strength never really succeeded in the period that followed. In addition, the presence necessary in the south sometimes tied up quite considerable forces. Otto's coronation as emperor in Rome in 962 linked the claim of the later Roman-German kings to the western imperial dignity for the rest of the Middle Ages. The Ottonians now exercised a hegemonic position of power in Latin Europe.

Under Otto II , the last remaining connections to the West Franconian-French Empire, which still existed in the form of family ties when he made his cousin Karl Duke of Niederlotharingia, were also broken. Karl was a descendant of the Carolingian family and at the same time the younger brother of the West Franconian King Lothar. But it did not become - as later claimed in research - a “faithless Frenchman” a feudal man of a “German” king. Such categories of thought were still unknown at the time, especially since the leading Frankish-Germanic strata of the West Frankish empire continued to speak their old German dialect for some time after the division. In more recent research, the Ottonian era is no longer understood as the beginning of “German history” in the narrower sense; this process dragged on into the 11th century. In any case, Otto II played off one cousin against the other in order to gain an advantage for himself by driving a wedge into the Carolingian family. Lothar's reaction was violent, and the argument was emotional on both sides. The consequences of this final break between the successors of the Frankish Empire only became apparent later. The French kingship was now viewed as independent of the emperor due to the emerging French self-confidence.

The integration of the church into the secular system of rule of the empire, which historians later referred to as the “ Ottonian-Salian imperial church system ”, reached its climax under Henry II . The imperial church system was one of the defining elements of its constitution until the end of the empire; the involvement of the church in politics was not in itself exceptional; the same can be observed in most of the early medieval empires of Latin Europe. Henry II demanded unconditional obedience from the clergy and the immediate implementation of his will. He completed royal sovereignty over the imperial church and became a “monk king” like no other ruler of the empire. But he not only ruled the church, he also ruled the empire through the church by filling important offices - such as that of chancellor - with bishops. Secular and ecclesiastical affairs were basically not differentiated and were negotiated equally at synods . This was not only the result of efforts to counterbalance the duchies' urge for greater independence, stemming from the Franconian-Germanic tradition, with a loyal counterweight to the king. Rather, Heinrich saw the kingdom as the “house of God”, which he had to look after as God's steward. At least now the kingdom was "holy".

High Middle Ages

The third important part of the empire was the Kingdom of Burgundy, which came under Conrad II , even if this development had already begun under Henry II: Since the Burgundian King Rudolf III. had no descendants, he named his nephew Heinrich as his successor and placed himself under the protection of the empire. In 1018 he even handed over his crown and scepter to Heinrich.

The rule of Konrad was further characterized by the evolving idea that the empire and its rule existed independently of the ruler and developed legal force. This is evidenced by Konrad's “ship metaphor” handed down by Wipo (see corresponding section in the article on Konrad II ) and his claim to Burgundy - because Heinrich was supposed to inherit Burgundy and not the realm. Under Konrad, the development of the ministerials began as a separate class of the lower nobility, by giving fiefs to the king's unfree servants. Important for the development of law in the empire were his attempts to push back the so-called divine judgments as legal means by applying Roman law, to which these judgments were unknown, in the northern part of the empire.

Konrad continued the imperial church policy of his predecessor, but not with his vehemence. Rather, he judged the church by what it could do for the kingdom. In the majority he called bishops and abbots with great intelligence and spirituality. However, the Pope did not play a major role in his appointments either. Overall, his rule appears to be a great "success story", which is probably also due to the fact that he ruled at a time when there was generally a kind of optimistic mood that led to the Cluniac reform at the end of the 11th century .

Henry III. took over a solid empire from his father Konrad in 1039 and, unlike his two predecessors, did not have to fight for power. Despite military actions in Poland and Hungary, he attached great importance to maintaining peace within the empire. This idea of a general peace, a peace of God , arose in the south of France and had spread throughout the Christian West from the middle of the 11th century. This was intended to curb the feuds and blood revenge, which had become more and more a burden on the functioning of the empire. The initiator of this movement was the Cluniac monasticism. At least on the highest Christian holidays and on the days that were sanctified by the Passion of Christ, i.e. from Wednesday evening to Monday morning, the arms should be silent and the "peace of God" should prevail.

Heinrich had to accept a hitherto completely unknown condition for the consent of the greats of the empire in the election of his son, who later became Henry IV , as king in 1053. Subordination to the new king should only apply if Henry IV proved to be the right ruler. Even if the power of the emperors over the church with Heinrich III. was at one of its climaxes - it was he who decided on the occupation of the holy throne in Rome - the balance of his reign is usually viewed negatively in recent research. Thus Hungary emancipated itself from the empire, which was previously an imperial fief, and several conspiracies against the emperor showed the unwillingness of the greats of the empire to submit to a strong kingship.

Due to the early death of Henry III. his only six-year-old son Heinrich IV came to the throne. His mother Agnes took over the guardianship of him until he was 15 in 1065. This resulted in a gradual loss of power and importance of the kingship. Due to the " coup d'état of Kaiserswerth ", a group of imperial princes led by the Archbishop of Cologne in Anno II temporarily seized the power of government. In Rome, the opinion of the future emperor no longer interested anyone at the next papal election. The annalist of the Niederaltaich monastery summarized the situation as follows:

"[...] but those present at court each looked after themselves as much as they could, and no one instructed the king what was good and just, so that much in the kingdom got into disorder"

The so-called investiture dispute was decisive for the future position of the imperial church . It was a matter of course for the Roman-German rulers to fill the vacant episcopal seats in the empire. Due to the weakness of the kingship during the reign of Henry's mother, the Pope, as well as clerical and secular princes, tried to appropriate royal possessions and rights. The later attempts to regain control of the king's power naturally met with little approval. When Heinrich tried in June 1075 to push through his candidate for the Milanese bishopric , Pope Gregory VII reacted immediately. In December 1075 Gregory banished King Heinrich and thus released all subjects from their oath of loyalty. The princes of the empire demanded from Heinrich that he should have the ban lifted by February 1077, otherwise it would no longer be recognized by them. Otherwise the Pope would be invited to resolve the dispute. Henry IV had to bow down and humiliated himself in the legendary walk to Canossa . The positions of power had turned into their opposite; In 1046 Heinrich III. still judged over three popes, now a pope was supposed to judge the king.

The son of Henry IV revolted against his father with the help of the Pope and forced his abdication in 1105 . The new King Heinrich V ruled in consensus with the clerical and secular greats until 1111. The close alliance between rulers and bishops could also be continued on the investiture question against the Pope. The solution found by the Pope was simple and radical. In order to ensure the separation of the spiritual tasks of the bishops from the secular tasks previously performed, as required by the church reformers, the bishops should return the rights and privileges they had received from the emperor or king in the last centuries. On the one hand, the bishops' duties to the empire were no longer applicable, and on the other hand, the king's right to influence the appointment of the bishops was also eliminated. Since the bishops did not want to forego their secular regalia , Heinrich captured the Pope and extorted the right of investiture and his coronation as emperor. Only the princes forced a compromise between Heinrich and the incumbent Pope Calixt II in the Worms Concordat in 1122. Heinrich had to renounce the investiture right with the spiritual symbols of ring and staff (per anulum et baculum) . The emperor was allowed to attend the election of bishops and abbots. The emperor was only allowed to grant the newly elected royal rights (regalia) with the scepter. Since then, the princes have been regarded as "the heads of the state". The kingdom was no longer represented by the king alone, but also by the princes.

After the death of Heinrich V in 1125 Lothar III. elected king, whereby he was able to prevail in the election against the Swabian Duke Friedrich II , the closest relative of the emperor, who died childless. Legitimation under inheritance law no longer determined the succession to the throne in the Roman-German Empire, but the choice of princes was decisive.

In 1138 Konrad from Staufer was raised to the rank of king. However, Konrad's wish to acquire the imperial crown was not to be fulfilled. His participation in the Second Crusade was also unsuccessful; he still had to turn back in Asia Minor. For this he succeeded in an alliance directed against the Normans with the Byzantine emperor Manuel I Komnenos .

In 1152, after the death of Konrad, his nephew Friedrich , the Duke of Swabia, was elected king. Friedrich, known as "Barbarossa", pursued a determined policy aimed at regaining imperial rights in Italy (see honor imperii ), for which Frederick made a total of six moves to Italy. In 1155 he was crowned emperor, but because of a campaign against the Norman Empire in southern Italy that had not taken place but was contractually guaranteed, tensions with the papacy developed, and relations with Byzantium also deteriorated. The northern Italian city-states, especially the rich and powerful Milan , resisted Frederick's attempts to strengthen the imperial administration in Italy (see the Reichstag of Roncaglia ). The so-called Lombard League was finally formed , which was able to assert itself militarily against the Hohenstaufen. At the same time there was a controversial papal election, with Pope Alexander III, who was elected with the majority of the votes . was initially not recognized by Friedrich. Only after it became clear that a military solution had no prospect of success (an epidemic raged in the imperial army outside Rome in 1167, defeat in the Battle of Legnano in 1176 ), an agreement was finally reached between the emperor and the pope in the Peace of Venice in 1177 . The northern Italian cities and the emperor also came to an understanding, although Friedrich was by no means able to achieve all of his goals.

In the empire, the emperor fell out with his cousin Heinrich , Duke of Saxony and Bavaria from the house of the Guelphs, after the two had worked closely together for over two decades. However, when Heinrich made his participation in an Italian march subject to conditions, the overpowering Duke Heinrich was overthrown by Frederick at the endeavors of the princes. In 1180 Heinrich was “tried” and the Duchy of Saxony was smashed and Bavaria was made smaller, from which, however, it was less the emperor than the territorial lords of the empire who benefited.

The emperor died in June 1190 in Asia Minor during a crusade. He was succeeded by his second eldest son, Heinrich VI. on. He had already been elevated to Caesar by his father in 1186 and has been considered Frederick's designated successor ever since. In 1191, the year of his coronation as emperor, Heinrich tried to take possession of the Norman kingdom in southern Italy and Sicily. Since he was married to a Norman princess and the ruling house of Hauteville had largely died out, he was also able to assert claims that were initially not militarily enforceable. It was not until 1194 that the conquest of southern Italy succeeded, where Heinrich sometimes proceeded with extreme brutality against opposing forces. In Germany Heinrich had to fight against the resistance of the Guelphs - in 1196 his inheritance plan failed . In return he pursued an ambitious and quite successful "Mediterranean policy", the aim of which was perhaps the conquest of the Holy Land or possibly even an offensive against Byzantium.

After the early death of Henry VI. In 1197 the last attempt to create a strong central power in the empire failed. After the double election of 1198, in which Philip of Swabia was elected in March in Mühlhausen / Thuringia and Otto IV in Cologne in June, two kings in the empire faced each other. Heinrich's son, Friedrich II. , Had been elected king as early as 1196 at the age of two, but his claims were brushed aside. Philip had already largely prevailed when he was murdered in June 1208. Otto IV was able to establish himself as ruler for a few years. His planned conquest of Sicily led to a break with his long-time patron Pope Innocent III. In the northern Alpine part of the empire, Otto increasingly lost approval due to the excommunication from the princes. The Battle of Bouvines in 1214 ended his rule and brought the final recognition of Frederick II. After the controversy for the throne, the empire began to develop a great deal of development towards writing down customs. The two legal books of the Sachsen and Schwabenspiegel are considered to be significant evidence of this . Many arguments and principles that should apply to the following king elections were formulated at that time. This development culminated in the middle of the 14th century after the experiences of the Interregnum in the determinations of the Golden Bull .

The fact that Frederick II, who had traveled to Germany in 1212 to enforce his rights there, stayed only a few years of his life and thus his reign in the German Empire after his recognition, gave the princes more room for maneuver. In 1220, Frederick chartered extensive rights to the ecclesiastical prince in the Confoederatio cum principibus ecclesiasticis in order to secure their approval for the election and recognition of his son Heinrich as Roman-German king. The privileges mentioned since the 19th century as Confoederatio cum principibus ecclesiasticis and Statutum in favorem principum (1232) formed the legal basis for the princes on which they could expand their power to closed, independent sovereigns . However, they were not so much stations of the loss of power for the kingship, but with the privileges a level of development was documented that the princes had already achieved in the expansion of their territorial rule.

In Italy, the highly educated Frederick II, who increasingly centralized the administration of the Kingdom of Sicily according to the Byzantine model, was involved in a conflict with the papacy and the northern Italian cities for years, with Frederick being denigrated as an antichrist . In the end, Friedrich seemed to have gained the upper hand militarily, since the emperor, who had been deposed by the Pope in 1245, died on December 13, 1250.

Late middle ages

At the beginning of the late Middle Ages , in the course of the fall of the Hohenstaufen and the subsequent interregnum up to the time of Rudolf von Habsburg, royal power fell into disrepair , although this was traditionally only weak. At the same time the power of the sovereigns and electors increased. The latter had exclusive royal suffrage since the late 13th century, so that the subsequent kings often strived for a coherent imperial policy with them. King Rudolf (1273–1291) succeeded once again in consolidating the kingship and securing the remaining imperial property as a result of the so-called revindication policy. Rudolf's plan for the coronation of the emperor failed, as did his attempt to impose a dynastic succession, which the imperial princes were not ready to do. However, the House of Habsburg gained important possessions in the south-east of the German part of the empire.

Rudolf's successor, Adolf von Nassau , sought rapprochement with the powerful kingdom of France, but with his policy in Thuringia he provoked the resistance of the imperial princes, who united against him. In 1298, Adolf von Nassau fell in battle against the new King Albrecht von Habsburg . Albrecht also had to fight against the resistance of the electors, who disliked his plans to increase the Habsburg power and who feared that he was planning to establish a hereditary monarchy. In the end, Albrecht was able to assert himself against the electors, but he submitted to Pope Boniface VIII in an oath of obedience and surrendered imperial territories to France in the west. On May 1, 1308, he fell victim to the murder of a relative.

The increased French expansion in the western border area of the empire since the 13th century had the consequence that the influence of the kingship in the former Kingdom of Burgundy continued to decline; a similar but less pronounced tendency emerged in imperial Italy (essentially in Lombardy and Tuscany ). It was not until Henry VII (1310-1313) moved to Italy that the imperial Italian policy was cautiously revived . King Henry VII, elected in 1308 and crowned in 1309, achieved a large degree of unity among the great houses in Germany and in 1310 won the Kingdom of Bohemia for his house. The House of Luxembourg rose to become the second important late medieval dynasty alongside the Habsburgs. In 1310 Heinrich set out for Italy. After Frederick II he was the first Roman-German king who was also able to obtain the imperial crown (June 1312), but his policy provoked the resistance of the Guelphs in Italy, the Pope in Avignon (see Avignon Papacy ) and the French king, who saw a new, power-conscious empire as a danger. Heinrich died in Italy on August 24, 1313 when he was about to embark on a campaign against the Kingdom of Naples. The Italian policy of the following late medieval rulers was much narrower than that of their predecessors.

In 1314, two kings, Ludwig IV of Wittelsbach and Friedrich of Habsburg, were elected. In 1325, a double kingship, hitherto completely unknown to the medieval empire, was created for a short time. After Frederick's death, Ludwig IV pursued a very self-confident policy in Italy as sole ruler and carried out an imperial coronation "free of the pope" in Rome. This brought him into conflict with the papacy. In this intensive discussion, the question of the papal license to practice medicine played a major role. In this regard, there were also political theoretical debates (see Wilhelm von Ockham and Marsilius von Padua ) and finally an increased emancipation of the electors or the king from the papacy, which was finally expressed in 1338 in the Kurverein von Rhense . Ludwig pursued an intensive domestic power policy since the 1330s by acquiring numerous territories. In doing so, however, he disregarded the consensual decision-making with the princes. Above all, this led to tensions with the House of Luxembourg , which openly challenged him with the election of Charles of Moravia in 1346. Ludwig died shortly afterwards and Karl ascended the throne as Charles IV .

The late medieval kings concentrated much more on the German part of the empire, while at the same time relying more than before on their respective domestic power. This resulted from the increasing loss of the remaining imperial property through an extensive pledge policy , especially in the 14th century. Charles IV can be cited as a prime example of a domestic power politician. He succeeded in expanding the Luxembourg power complex to include important areas; In return, however, he renounced imperial estates, which were pledged on a large scale and ultimately lost to the empire, and in fact he ceded areas in the west to France. In return, Karl achieved a far-reaching balance with the papacy and was crowned emperor in 1355, but renounced a resumption of the old Italian policy in the Staufer style. But above all, with the Golden Bull of 1356, he created one of the most important "basic imperial laws" in which the rights of the electors were finally established and which had a decisive influence on the future policy of the empire. The Golden Bull remained in force until the empire was dissolved. During Karl's reign the so-called Black Death - the plague - broke out, which contributed to a serious mood of crisis and in the course of which there was a significant decline in the population and pogroms against the Jews . At the same time, however, this time also represented the heyday of the Hanseatic League , which became a major power in northern Europe.

With the death of Charles IV in 1378, the power of the Luxembourgers in the empire was soon lost, as the complex of domestic power he had created quickly fell apart. His son Wenzel was deposed by the four Rhenish electors on August 20, 1400 because of his apparent inability. Instead, the Count Palatine of the Rhine, Ruprecht , was elected the new King. However, his power base and resources were far too few to develop effective government activity, especially since the Luxembourgers did not accept the loss of royal dignity. After Ruprecht's death in 1410, Sigismund , who had been King of Hungary since 1387, was the last Luxembourger to take the throne. Sigismund had to struggle with considerable problems, especially since he no longer had any domestic power in the empire, but in 1433 he achieved the dignity of emperor. Sigismund's political sphere of action extended far into the Balkans and Eastern Europe.

In addition, ecclesiastical political problems arose during this period, such as the Western Schism , which could only be eliminated under Sigismund with recourse to conciliarism . From 1419 the Hussite Wars presented a great challenge. The previously economically flourishing countries of the Bohemian Crown were largely devastated and the neighboring principalities found themselves in a constant threat from Hussite military campaigns. The disputes ended in 1436 with the Basel compacts , which recognized the Utraquist Church in the Kingdom of Bohemia and in the Margraviate of Moravia . The struggle against the Bohemian heresies led to an improvement in relations between the Pope and the Emperor.

With the death of Sigismund in 1437, the house of Luxembourg went extinct in a direct line. The royal dignity passed to Sigismund's son-in-law Albrecht II and thus to the Habsburgs , who they were able to maintain almost continuously until the end of the empire. Friedrich III. For a long time he largely stayed out of direct imperial business and had to contend with some political problems, such as the conflict with the Hungarian King Matthias Corvinus . In the end, however, Frederick secured the Habsburg position of power in the empire, the Habsburg claims to larger parts of the disintegrated rulership complex of the House of Burgundy, and the succession to the kings for his son Maximilian . The empire also underwent a structural and constitutional change during this time, in a process of “designed compression” ( Peter Moraw ), the relationships between the members of the empire and the kingship became closer.

Early modern age

Imperial reform

Historians see the early modern empire as a new beginning and rebuilding and by no means as a reflection of the Hohenstaufen rule in the High Middle Ages . Because the contradiction between the claimed holiness, the global claim to power of the empire and the real possibilities of the empire had become too clear in the second half of the 15th century. This triggered a journalistically supported imperial constitutional movement, which was supposed to revive the old "healthy conditions", but ultimately led to radical innovations.

Under the Habsburgs Maximilian I and Charles V , the empire regained recognition after its decline, the office of emperor was firmly linked to the newly created imperial organization. In line with the reform movement, Maximilian initiated a comprehensive reform of the empire in 1495, which provided for an eternal land peace , one of the most important projects of the reform proponents, and an empire-wide tax, the common penny . It is true that these reforms were not fully implemented, because of the institutions that emerged from it, only the newly formed Reichskreis and the Reichskammergericht survived. Nevertheless, the reform was the basis for the modern empire. With it it received a much more precise control system and an institutional framework. For example, the possibility of bringing subjects to trial against one's sovereignty before the Reich Chamber of Commerce promoted peaceful conflict resolution in the Reich. The interplay between the emperor and the imperial estates, which had now been established, was to be formative for the future. The Reichstag was also formed at that time and was the central political forum of the Reich until its end.

Reformation and Religious Peace

So set, organize, want and command. that in addition to no one, whatever their dignity, status or essence, for the sake of any cause, such as the names, would like to have, even in whatever appearances it happens, arguing, warring, robbing, perceiving, overturning, besieging the other, even for the sake of it Do not serve yourself or someone else on his behalf, dismantle some of the Castle, Städt, Marckt, Fortification, Dörffer, Höffe and Weyler, or without the other's will with mighty deed take it with a violent act or damage it dangerously with fire or in other ways

The first half of the 16th century was marked on the one hand by further legalization and thus a further consolidation of the empire, for example through the enactments of Imperial Police Regulations 1530 and 1548 and the Constitutio Criminalis Carolina in 1532. On the other hand, the in disintegrating the religious schism caused by the Reformation at this time. The fact that individual regions and territories turned away from the old Roman Church presented the empire with an acid test, not least because of its claim to holiness.

The Edict of Worms of 1521, in which the imperial ban on Martin Luther (after the papal ban on the Church, Decet Romanum Pontificem ) was made mandatory, did not yet offer any leeway for a policy that was friendly to the Reformation. Since the edict was not observed in the whole Reich, the decisions of the next Reichstag deviated from it. The mostly imprecise and ambiguous compromise formulas of the Reichstag gave rise to a new legal dispute. For example, the Nuremberg Diet of 1524 declared that everyone should obey the Edict of Worms, as much as possible . A final peace solution could not be found, however, one shuffled from one mostly temporary compromise to the next.

This situation was not satisfactory for either side. The Protestant side had no legal security and lived for several decades in fear of a religious war. The Catholic side, especially Emperor Charles V, did not want to accept a permanent religious split in the empire. Charles V, who initially did not take the Luther case seriously and did not recognize its scope, did not want to accept this situation because, like the medieval rulers, he saw himself as the guardian of the one true Church. The universal empire needed the universal church; however, his coronation as emperor in Bologna in 1530 would be the last to be performed by a pope.

After much hesitation, Karl imposed a ban on the leaders of the Evangelical Schmalkaldic League in the summer of 1546 and initiated the military execution of the Reich . This dispute went down in history as the Schmalkaldic War of 1547/48. After the victory of the emperor, the Protestant princes had to accept the so-called Augsburger Interim at the armored Augsburger Reichstag of 1548 , which at least granted them the lay chalice and the priestly marriage. This very mild outcome of the war for the Protestant imperial estates was due to the fact that Karl, in addition to religious-political goals, also pursued constitutional ones, which would have led to the undermining of the estates' constitution and a quasi-central government of the emperor. These additional goals earned him the resistance of the Catholic imperial estates, so that no satisfactory solution to the religious question was possible for him.

The religious disputes in the empire were integrated into Charles V's conception of a comprehensive Habsburg empire, a monarchia universalis that would encompass Spain, the Austrian hereditary lands and the Holy Roman Empire. However, he did not succeed in making the empire hereditary, nor in changing the imperial crown back and forth between the Austrian and Spanish lines of the Habsburgs. At the same time, Charles found himself in conflict with France, which was mainly fought in Italy, while the Turks conquered Hungary after 1526. The military conflicts tied up considerable resources.

The Prince's War of the Saxon Elector Moritz von Sachsen against Karl and the resulting Passau Treaty of 1552 between the warlords and the later Emperor Ferdinand I were the first steps towards a permanent religious peace in the empire, which led to the Augsburg Imperial and Religious Peace in 1555. The balance that took place at least for the time being was also made possible by the decentralized rulership structure of the empire, where the interests of the sovereigns and the empire repeatedly made it necessary to find a consensus, whereas in France with its centralized royal power during the 16th century, a bloody struggle between the Catholic royalty and individual Protestant leaders came.

The Peace of Augsburg was not only important as a religious peace, it also had an important constitutional role, as important constitutional political decisions were made through the creation of the Reich Execution Order. These steps had become necessary due to the Second Margrave War of Kulmbach Margrave Albrecht Alcibiades of Brandenburg-Kulmbach , which raged in the Franconian region from 1552 to 1554 . Albrecht extorted money and even territories from various Frankish empire territories. Emperor Charles V did not condemn this, he even took Albrecht into his service and thereby legitimized the breach of the eternal peace. Since the affected territories refused to accept the robbery of their territories confirmed by the emperor, Albrecht devastated their land. In the northern empire troops were formed under Moritz von Sachsen to fight Albrecht. An imperial prince and later King Ferdinand, not the emperor, had initiated military countermeasures against the peace-breaker. On July 9, 1553, the bloodiest battle of the Reformation times in the empire, the Battle of Sievershausen , in which Moritz of Saxony died.

The order of execution adopted at the Reichstag in Augsburg in 1555 included the constitutional weakening of the imperial power, the anchoring of the imperial principle and the full federalization of the empire. In addition to their previous duties, the imperial circles and local imperial estates also received responsibility for enforcing the judgments and appointing the assessors of the imperial chamber court. In addition to the coinage, they were given other important, previously imperial tasks. Since the emperor had proven to be incapable and too weak to carry out one of his most important tasks, the maintenance of peace, his role was now fulfilled by the imperial estates associated with the imperial circles.

Just as important as the execution order was the religious peace proclaimed on September 25, 1555, with which the idea of a denominationally unified empire was abandoned. The sovereigns were given the right to determine the denomination of their subjects, succinctly summarized in the formula whose rule, whose religion . In Protestant areas, ecclesiastical jurisdiction passed to the sovereigns, making them a kind of spiritual leader of their territory. It was also stipulated that ecclesiastical imperial estates, i.e. archbishops, bishops and imperial prelates, had to remain Catholic. These and a few other determinations led to a peaceful solution to the religious problem, but also manifested the increasing division of the empire and in the medium term led to a blockade of the imperial institutions.

After the Reichstag in Augsburg, Emperor Karl V resigned from his office and handed power over to his brother, the Roman-German King Ferdinand I. Karl's policy inside and outside the empire had finally failed. Ferdinand restricted the emperor's rule to Germany again, and he succeeded in bringing the imperial estates back into closer ties with the empire, thereby strengthening it again. That is why Ferdinand is often referred to as the founder of the modern German Empire.

Confessionalization and the Thirty Years' War

Until the beginning of the 1580s there was a phase in the empire without major armed conflicts. Religious peace had a stabilizing effect and the imperial institutions such as imperial circles and the imperial chamber court developed into effective and recognized instruments for securing peace. During this time, however, the so-called confessionalization took place, i.e. the consolidation and demarcation of the three denominations Protestantism, Calvinism and Catholicism from one another. The associated development of early modern forms of government in the territories brought constitutional problems to the empire. The tensions increased to such an extent that the empire and its institutions were no longer able to exercise their role as arbitrator, which was above the denominations, and were effectively blocked at the end of the 16th century. As early as 1588, the Reich Chamber of Commerce was no longer able to act.

Since the Protestant estates at the beginning of the 17th century also no longer recognized the Reichshofrat , which was exclusively occupied by the Catholic Emperor, the situation escalated further. At the same time, the Kurfürstenkolleg and the imperial circles split into confessional groups. A Reichsdeputationstag in 1601 failed due to the contradictions between the parties and in 1608 a Reichstag in Regensburg was ended without a Reich adoption because the Calvinist Electoral Palatinate, whose confession was not recognized by the Emperor, and other Protestant estates had left it.

Since the imperial system was largely blocked and the protection of the peace was supposedly no longer given, six Protestant princes founded the Protestant Union on May 14, 1608 . Other princes and imperial cities later joined the union, but Electoral Saxony and the north German princes stayed away. In response to the Union, Catholic princes and cities founded the Catholic League on July 10, 1609 . The league wanted to maintain the previous imperial system and preserve the predominance of Catholicism in the empire. The Reich and its institutions were finally blocked and incapable of acting.

The lintel in Prague was the trigger for the great war in which the emperor initially achieved great military successes and also tried to exploit them politically for his position of power over the imperial estates. In 1621, Emperor Ferdinand II ostracized the Palatinate Elector and Bohemian King Friedrich V and transferred the electoral dignity to Maximilian I of Bavaria . Ferdinand had previously been elected emperor by all, including the Protestant, electors on August 19, 1619, despite the beginning of the war.

The decree of the edict of restitution on March 6, 1629 was the last significant act of law by an emperor in the empire and, like Frederick V's ostracism, arose from the imperial claim to power. This edict required the implementation of the Augsburg Imperial Peace according to a Catholic interpretation. Accordingly, all arches, monasteries and dioceses that had been secularized by the Protestant rulers since the Passau Treaty were to be returned to the Catholics. In addition to the re-Catholicization of large Protestant areas, this would have meant a significant strengthening of the imperial position of power, since questions of religious policy had previously been decided by the emperor together with the imperial estates and electors. In contrast, an interdenominational coalition of the electors was formed. They did not want to allow the emperor to issue such a drastic edict without their consent.

The electors forced the emperor to dismiss the imperial generalissimo Wallenstein at the Regensburg Electoral Congress in 1630 under the leadership of the new Catholic elector Maximilian I and to agree to a review of the edict. Also in 1630 Sweden entered the war on the side of the Protestant imperial estates. After the imperial troops had been defeated by Sweden for a number of years, the emperor succeeded in winning the battle of Nördlingen again in 1634. In the subsequent Peace of Prague between the Emperor and Electoral Saxony of 1635, Ferdinand had to suspend the edict of restitution for forty years, based on the status of 1627. But the head of the empire emerged stronger from this peace, since all alliances of the imperial estates except for the Kurverein were declared dissolved and the emperor was granted the supreme command of the imperial army . But the Protestants also accepted this strengthening of the emperor. The religious-political problem of the Edict of Restitution had in fact been postponed by 40 years, since the emperor and most of the imperial estates agreed that the political unification of the empire, the cleansing of the empire's territory from foreign powers and the end of the war were most urgent.

After France openly entered the war in order to prevent a strong imperial-Habsburg power in Germany, the balance shifted again to the detriment of the emperor. At this point, at the latest, the original German denominational war within the empire had turned into a European hegemonic struggle. So the war went on, since the religious and constitutional problems, which had at least provisionally been resolved in the Peace of Prague, were of secondary importance for the powers Sweden and France located on imperial territory. In addition, as already indicated, the Peace of Prague had serious shortcomings, so that the internal disputes within the empire continued.

From 1641, individual imperial estates began to conclude separate peace, as it was hardly possible to organize broad-based resistance by the empire in the thicket of denominational solidarity, traditional alliance policy and the current war situation. The first major imperial estate was the Elector of Brandenburg in May 1641. He made peace with Sweden and released his army, which was not possible according to the provisions of the Peace of Prague, as it was nominally part of the Imperial Army. Other imperial estates followed; so in 1645 Electoral Saxony made peace with Sweden and in 1647 Electoral Mainz with France.

Against the will of the emperor, since 1637 Ferdinand III. Who originally wanted to represent the kingdom at the now impending peace talks in Munster and Osnabruck, in accordance with the Peace of Prague alone, the imperial estates, supported by France were on their liberty pounded, admitted to the talks. This dispute, known as the admissions question , finally nullified the system of the Peace of Prague with the strong position of the emperor. Ferdinand originally only wanted to clarify European questions in the Westphalian negotiations and make peace with France and Sweden and deal with the German constitutional problems at a subsequent Reichstag, where he could have appeared as a glorious peace-maker. The foreign powers would have had no place in this Reichstag.

Peace of Westphalia

May there be a general and everlasting Christian peace [...] and this should be honestly and seriously observed and observed, so that each part promotes the benefit, honor and advantage of the other and that both on the part of the entire Roman Empire with the Kingdom of Sweden as May also on the part of the Kingdom of Sweden loyal neighborhood, true peace and genuine friendship with the Roman Empire grow anew and flourish.

The Kaiser, Sweden and France agreed on peace negotiations in Hamburg in 1641 , during which the fighting continued. The negotiations began in 1642/43 in parallel in Osnabrück between the emperor, the evangelical imperial estates and Sweden and in Münster between the emperor, the catholic imperial estates and France. The fact that the emperor did not represent the empire alone was a symbolically important defeat. The imperial power, which had emerged stronger from the Peace of Prague, was again up for grabs. The imperial estates, regardless of their denomination, considered the Prague order so dangerous that they saw their rights better protected when they did not sit across from the emperor alone, but when the negotiations on the imperial constitution took place under the eyes of abroad. But this was also very beneficial to France, which wanted to limit the power of the Habsburgs and therefore campaigned for the participation of the imperial estates.

Both negotiating cities and the connecting routes between them had been declared demilitarized in advance (but this was only carried out for Osnabrück) and all embassies were given safe conduct. Delegations from the Republic of Venice , the Pope and Denmark traveled to mediate, and representatives of other European powers flocked to Westphalia. In the end, all European powers except the Ottoman Empire, Russia and England were involved in the negotiations. In addition to the negotiations between the Reich and Sweden, the negotiations in Osnabrück actually became a constitutional convention at which constitutional and religious-political problems were dealt with. In Münster negotiations took place on the European framework conditions and the feudal changes in relation to the Netherlands and Switzerland. Furthermore, the Peace of Munster between Spain and the Republic of the Netherlands was negotiated here.

Until the end of the 20th century, the Peace of Westphalia was viewed as destructive to the empire. Fritz Hartung justified this with the argument that the peace treaty had deprived the emperor of all handicaps and granted the imperial estates almost unlimited freedom of action, that the empire had been “split up”, “crumbled” - it was therefore a “national misfortune”. Only the religious-political question had been resolved, but the empire had fallen into a state of paralysis that ultimately led to its disintegration.

In the time immediately after the Peace of Westphalia, and also during the 18th century, the peace treaty was viewed quite differently. It was greeted with great joy and was considered the new constitution that applies wherever the emperor, with his privileges and as a symbol of the unity of the empire, is recognized. Through its provisions, the peace established the territorial lordships and the various denominations on a uniform legal basis and established the mechanisms established and proven after the constitutional crisis at the beginning of the 16th century, and rejected those of the Peace of Prague. Georg Schmidt summarizes:

“Peace has produced neither state fragmentation nor princely absolutism. [...] The peace emphasized the freedom of the estates, but did not make sovereign states out of the estates. "

All imperial estates were granted full sovereign rights and the right of alliance, which was annulled in the Peace of Prague, was reassigned. However, this did not mean the full sovereignty of the territories, which can also be seen from the fact that this right is listed in the contract text amid other rights that have been exercised for a long time. The right of alliances - this also contradicts the full sovereignty of the territories of the empire - was not allowed to be directed against the emperor and the empire, the peace of the land or against this treaty and, according to contemporary legal scholars, was in any case a long-established customary law (see also the section on Customs and Customs ) of the imperial estates which was only stipulated in writing in the contract.

In the religious-political part, the imperial estates practically withdrew from themselves the authority to determine the denomination of their subjects. Although the Augsburg Religious Peace was confirmed as a whole and declared inviolable, the disputed questions were reorganized and legal relationships were fixed to the status of January 1, 1624 or reset to the status on this deadline. For example, all imperial estates had to tolerate the other two denominations if they already existed on their territory in 1624. All possessions had to be returned to the owner at the time, and all subsequent provisions to the contrary by the emperor, the imperial estates or the occupying powers were declared null and void.

The second religious peace certainly did not bring any progress for the idea of tolerance or for individual religious rights or even human rights. But that was not its aim either. It should have a peacemaking effect through further legalization. Peace and not tolerance or secularization was the goal. It is obvious that this succeeded in spite of all the setbacks and occasional casualties in later religious disputes.

The treaties of Westphalia brought the long-awaited peace to the empire after thirty years. The empire lost some territories to France and effectively released the Netherlands and the old Confederation from the Reichsverband. Otherwise, not much changed in the empire, the power system between the emperor and the imperial estates was rebalanced without any major shift in weight compared to the situation before the war, and imperial politics was not deconfessionalized, only the way the denominations were dealt with. Neither was

“[The] Reichsverband is still damned to freeze - these are fervently cherished research myths for a long time. Seen soberly, the Peace of Westphalia, this alleged national misfortune, loses much of its horror, but also much of its supposedly epoch-making character. The fact that he destroyed the idea of the empire and the empire is the most glaring of all the false judgments that are circulating about the Peace of Westphalia. "

Until the middle of the 18th century

After the Peace of Westphalia, a group of princes, united in the Princely Association, pushed for radical reforms in the empire, which in particular were intended to limit the supremacy of the electors and to extend the royal electoral privilege to other imperial princes. At the Reichstag of 1653/54, which according to the provisions of the peace should have taken place much earlier, this minority could not assert itself. In the imperial farewell of this Reichstag, called the youngest - this Reichstag was the last before the body came into force - it was decided that the subjects would have to pay taxes to their masters so that these troops could support. This often led to the formation of standing armies in various larger territories. These were known as the Armied Imperial Estates .

Nor did the empire disintegrate, since too many classes had an interest in an empire that could guarantee their protection. This group included especially the smaller estates, which could practically never become a state of their own. The aggressive, expansive policy of France on the western border of the empire and the danger of the Turks in the east made it clear to almost all estates the need for a sufficiently closed imperial union and an empire head capable of acting.

Emperor Leopold I , whose work has only been examined in more detail since the 1990s, has ruled the empire since 1658 . His work is described as clever and far-sighted, and measured against the starting position after the war and the low point of the imperial reputation, it was also extremely successful. By combining various instruments of rule, Leopold succeeded in re-tying the smaller as well as the larger imperial estates to the imperial constitution and to the empire. Particularly noteworthy here are his marriage policy, the means of raising his rank and the awarding of all sorts of melodious titles. Nevertheless, the empire's centrifugal forces increased. The award of the ninth electoral dignity to Ernst August von Hannover in 1692 stands out in particular . The concession to the Brandenburg Elector Friedrich III also falls into this category . , To 1,701 for not belonging to the Empire Duchy of Prussia to King of Prussia crowned to be allowed.

After 1648 the position of the imperial circles was further strengthened and they were given a decisive role in the imperial war constitution . In 1681, because of the threat to the empire from the Turks, the Reichstag passed a new constitution for the war in which the troop strength of the imperial army was set at 40,000 men. The imperial districts should be responsible for the formation of the troops . The Perpetual Reichstag offered the emperor the opportunity to bind the smaller imperial estates to himself and to win them over to his own politics. Thanks to the improved options for arbitration, the emperor was able to increase his influence on the empire again.

The fact that Leopold I opposed the reunification policy of the French King Louis XIV and tried to persuade the imperial circles and estates to oppose the French annexations of imperial territories shows that imperial policy was not yet, as it was under his successors in the 18th century, had become a mere appendage of the Habsburg great power politics. It was also during this time that the great power of Sweden was pushed back from the northern regions of the empire in the Swedish-Brandenburg War and the Great Northern War .

Dualism between Prussia and Austria

From 1740 the two largest territorial complexes of the empire, the Archduchy of Austria and Brandenburg-Prussia , began to grow more and more out of the imperial association. The house Austria was after the victory over the Turks in the Great Turkish War after 1683 large areas outside the realm acquire, whereby the focus of the Habsburg policy shifted to the southeast. This became particularly clear under the successors of Emperor Leopold I. It was similar with Brandenburg-Prussia, here too part of the territory was outside the empire. In addition to the increasing rivalry, which put heavy demands on the structure of the empire, there were also changes in the thinking of the time.

Until the Thirty Years' War it was very important for a ruler's reputation what titles he held and what position he was in the hierarchy of the empire and the European nobility, now other factors such as the size of the territory and economic and military power came into play more in the foreground. The view prevailed that only the power that resulted from this quantifiable information really counts. According to historians, this is a late consequence of the great war, in which time-honored titles, claims and legal positions, especially of the smaller imperial estates, played almost no role and were subordinated to the fictitious or actual constraints of the war.

However, these categories of thought were not compatible with the previous system of the empire, which was supposed to guarantee the empire and all its members legal protection of the status quo and protect them from an excess of power. This conflict can be seen, among other things, in the work of the Reichstag. Its composition did differentiate between electors and princes, high aristocracy and city magistrates, Catholic and Protestant, but not, for example, between classes that maintained a standing army and those that were defenseless. This discrepancy between actual power and traditional hierarchy led to the desire of the large, powerful estates for a loosening of the Reichsverband.

In addition, there was Enlightenment thinking , which questioned the conservative, conservative character, the complexity, and even the idea of the empire itself and presented it as "unnatural". The idea of equality between people could not be brought into harmony with the imperial idea of preserving what was already there and securing its assigned place in the structure of the empire for each class.

In summary, it can be said that Brandenburg-Prussia and Austria no longer fit into the Reichsverband, not only because of the sheer size, but also because of the internal constitution of the two territories that have become states. Both had reformed the countries, which were originally decentralized and based on estates, and broke the influence of the estates. This was the only way to manage and preserve the various inherited and conquered countries sensibly and to finance a standing army. This reform path was closed to the smaller territories. A sovereign who had undertaken reforms of this magnitude would inevitably have come into conflict with the imperial courts, as they would have stood by the estates, whose privileges a sovereign would have violated. The Kaiser, in his role as the Austrian sovereign, did not, of course, have to fear the Reichshofrat he occupied as much as other sovereigns, and in Berlin people hardly cared about the imperial institutions anyway. An execution of the judgments would in fact not have been possible. This different inner constitution of the two great powers also contributed to the estrangement from the empire.

The rivalry between Prussia and Austria , known as dualism , gave rise to several wars in the 18th century. The two Silesian Wars Prussia won and received Silesia, while the War of the Austrian Succession ended in Austria's favor. During the War of Succession, a Wittelsbacher came to the throne with Charles VII , but could not assert himself without the resources of a great power, so that after his death in 1745 with Franz I Stephan of Lothringen , Maria Theresa's husband , a Habsburg (-Lothringer ) was chosen.

These conflicts were devastating for the empire. Prussia did not want to strengthen the empire, but wanted to use it for its own purposes. The Habsburgs, too, who were disgruntled by the alliance of many imperial estates with Prussia and the election of a non-Habsburg to the imperial throne, were now much more unequivocal than before on a policy that focused solely on Austria and its power. The imperial title was almost only sought because of its sound and the higher rank compared to all European rulers. The imperial institutions had degenerated into sidelines of power politics and the constitution of the empire no longer had much to do with reality. Prussia tried to hit the Kaiser and Austria by instrumentalizing the Reichstag. Emperor Joseph II in particular withdrew almost entirely from imperial politics. Initially, Joseph II tried to reform the imperial institutions, especially the imperial chamber court, but failed due to the resistance of the imperial estates, which broke away from the imperial association and therefore no longer wanted the court to talk into their "internal" affairs. Joseph gave up in frustration.