From the spirit of the law

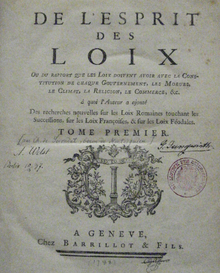

The book On the Spirit of Laws by Charles de Secondat, Baron de Montesquieu , was first published in Geneva in 1748, in the early days of the Enlightenment , under the French original title De l'esprit des loix . It was first published anonymously because Montesquieu's works were censored , and in fact the book was indexed in 1751 .

The Spirit of Laws is a key text of the Enlightenment and Montesquieu's major work. The French subtitle of the original edition already shows the scope of the topics covered: Ou du rapport que les Loix doivent avoir avec la Constitution de chaque Gouvernement, les Moeurs, le Climat, la Religion, le Commerce & c., À quoi l'Auteur ajouté des recherches nouvelles sur les Loix Romaines touchant les Successions, sur les Loix Françoises et sur les Loix Féodales (German: "Or of the relationship that the laws have with the constitution of every government , with morals , climate, religion, trade etc., to which the author has added new studies on the Roman laws of succession, the French laws and the feudal laws ”).

content

The book is based on Montesquieu's studies of the rise and fall of the Roman Empire . Unlike the Christian philosophy of history, which viewed the decline of Rome as the work of divine providence, Montesquieu wanted to find a factual explanation. He has shaped these insights into a state and social theory in the spirit of the law and tried to define the determining factors according to which individual states have developed their respective government and legal systems. The “general spirit” (“esprit général”) of a nation results from these factors, and this in turn corresponds to the spirit of its laws. According to Montesquieu, their totality is not a quasi arbitrary sum of laws, but an expression of the natural environment, the history and the “character” of a people.

Part one: Government doctrine

The first part of the work presents a doctrine of government. Montesquieu proposes a new classification of the forms of government, which deviates significantly from the Aristotelian generally accepted up until then . He differentiates between republic , monarchy and despotism .

"Republican is the government in which the people as a body or only part of the people have sovereign power. A monarchy is the government in which a single man rules, but according to fixed and promulgated laws, whereas in the despotic government a single man without rules and laws does everything according to his will and stubbornness. "

The main distinguishing feature is not the number of rulers, but whether it is ruled according to laws, as in republic and monarchy, or without laws, as in despotism. In addition, as with Aristotle , the forms of government differ in the number of rulers. The republic is a democracy or an aristocracy , depending on whether "the people as a body have sovereign power" (ibid., Chapter 2), or only a part of the people, namely the aristocrats. If only one rules, the government is monarchy or despotism, depending on whether it is ruled by law or not.

With his description of the monarchy as a form of government bound by law, Montesquieu is considered to be one of the founders of the idea of constitutional monarchy .

Montesquieu distinguishes the nature of each form of government from its principle.

“The difference between the nature of government and its principle is as follows: its nature makes it what it is, its principle makes it act. One is the special structure, the other is the human passions that set it in motion. "

The principle of democracy is virtue, that of the aristocracy is self-discipline, that of the monarchy is honor and that of despotism is terror.

Second part: separation of powers

In the second part of the work the Enlightenment explains his theory of the division of powers . He asks whether it is possible to create a society in which the citizen is free and answers the question in the affirmative:

"A state can be built in such a way that nobody is forced to do something that the law does not oblige them to do, and nobody is forced to refrain from doing something that the law permits."

“Furthermore, there is no freedom unless the judicial power is separated from the legislative and executive. If it is connected with the legislative power, power over the life and liberty of the citizens would be arbitrary because the judge would be the legislator. If it were linked to the executive, the judge would have the power of an oppressor. "

The freedom as a civil right is provided when the compulsory state is limited solely to the laws. If the state only exercises the socially absolutely necessary coercion, the maximum possible civil freedom is given. So the first condition for civil liberty is that the rulers are bound by laws. The second condition, however, is to deprive the rulers of power over the laws. “It would be to be feared that the same monarch or the same senate would issue tyrannical laws and then enforce them in a tyrannical way” (ibid., Chap. 6), so that the arbitrary acts of the rulers are clothed in laws, but are nevertheless arbitrary acts. Therefore, so must the Montesquieu legislative from the executive be empowered separately. The laws limit the coercion, which endangers civil liberty and which the rulers exert on the citizens, to what is absolutely necessary only if they are withdrawn from their arbitrariness. He drafts his theory of the division of powers using the example of the English constitution. His remarks hardly describe the English conditions at that time, rather they represent an ideal, designed on the basis of the English conditions.

Third part: causes of the laws

Finally, in the third part, Montesquieu shows the “natural” causes of the laws in climatic conditions and the “esprit général”, the general spirit of the peoples.

German language edition

- Kurt Weigand (selection of texts, translation, introduction). Reclams Universal Library , 8953/57. Philipp Reclam, Stuttgart 1965; Revised and bibliographically supplemented new edition: 2011, ISBN 978-3-15-008953-8 . 443 pages.

literature

- Panajotis Kondylis : Montesquieu and the Spirit of Laws . Akademie Verlag, Berlin 1996, ISBN 3-05-002983-8 .

- Paul-Ludwig Weinacht (Ed.): Montesquieu: 250 Years "Spirit of Laws". Contributions from political science, jurisprudence and Romance studies . Nomos Verlagsgesellschaft, Baden-Baden 1999, ISBN 3-7890-6091-7 .