Second lintel in Prague

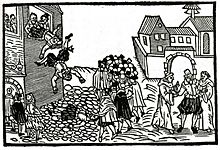

The second lintel in Prague on May 23, 1618 is the act of violence committed by representatives of the Protestant estates in the form of defenestration ( Latin for lintel) against the royal governors Jaroslaw Borsita Graf von Martinitz and Wilhelm Slawata von Chlum and Koschumberg as well as the chancellery secretary Philipp Fabricius . It marks the beginning of the Thirty Years War and represents an important turning point in the history of Europe.

history

The lintel occurred as a beacon during the Bohemian uprising . The predominantly Protestant estates accused their Catholic sovereign, Emperor Matthias and the Bohemian King Ferdinand of Styria, who was elected his successor in 1617 (also Emperor after 1619), of violating the religious freedom of Protestants granted by Emperor Rudolf II in his majesty letter of 1609. The outrage was triggered by the demolition of the Protestant church in the monastery grave and the closure of the St. Wenceslas Church in Braunau .

After the dissolution of the assembly of estates, almost 200 representatives of the Protestant estates under the leadership of Heinrich Matthias von Thurn moved to Prague Castle on May 23, 1618 and after an improvised show trial threw the royal governors present in the Bohemian court chancellery there, Jaroslaw Borsita Graf von Martinitz and Wilhelm Slavata von Chlum and Koschumberg as well as the office secretary Philipp Fabricius from a window about 17 meters deep into the moat, whereby all three survived, one of them injured in the head. Martinitz, who was first rushed out, reports on Slavata's fall:

- First they smashed the fingers of his hand, with which he was holding on, to the blood and threw him down through the window without a hat, in a black velvet coat. He fell to the ground, rolled 8 cubits deeper than Martinitz into the ditch and got his head very entangled in his heavy coat.

Slavata reports the following about his own fall, speaking of himself in the third person:

- Count Slavata hit the stone cornice of the bottom window and his head fell on a stone on the ground.

The Slavata case ended roughly, albeit a bit slowed down by a window ledge. Martinitz writes about the secretary's case:

- In the end we threw Magister Phillip Fabricius, Roman Imperial Councilor and Royal Bohemian Secretary […] into the ditch.

The mild outcome of the act of violence was justified in various ways. The widespread explanation that the defenestrians ended up on a dung heap that had accumulated under the window is likely an anecdotal invention of later times and is not mentioned in the memories of those involved in either party. It is also unlikely that there was a dung heap in the moat of Prague Castle, of all places, under the Council Chancellery windows. The dunghill legend is probably the Protestant answer to the fact that Catholics declared the rescue of the defenestrated with the help of the Virgin Mary .

The reasons for the mild outcome were probably the fashion at the time and the cool weather. All those involved wore wide, heavy coats, which greatly dampened the fall. In addition, the windows from which the three were thrown were very small and they could not be carried outside with swing. In addition, all three fought back and Martinitz was still holding on to the ledge when he was already hanging outside. In addition, the wall below the window is not straight, but sloping outwards, so that the three of them probably slipped down rather than fell.

The Bohemian estates were amazed that the three had survived the fall and hastily sent them a few shots, all of which missed their target as the crowd at the windows prevented the shooters from aiming properly. The governors found shelter and protection with the Catholic noblewoman Polyxena von Lobkowicz .

This defenestration was a tougher version of throwing a gauntlet , a declaration of war on the emperor. The lintel marked the beginning of the uprising of the Bohemian Protestants against the Catholic Habsburgs and is considered to trigger the Thirty Years War (1618–1648).

Media reception

- The second lintel in Prague. 85-minute television documentary by Zdenek Jirasky ( Arte , Česká televize , France / Czech Republic 2018).

See also

- First lintel in Prague (1419)

- Third lintel in Prague (1948)

literature

- Hans Sturmberger : Uprising in Bohemia. The beginning of the Thirty Years War. Oldenbourg, Munich / Vienna 1959.

- Peter Milger: The Thirty Years War. Against the country and its people. Orbis, Munich 2001, ISBN 3-572-01270-8 .

Web links

- Entry on the second lintel on Radio Prague

- Historical illustration from 1627: True contrafacture like the Kays. Räthe had been thrown out the window. ( Digitized version )