Germany in the Middle Ages

The article Germany in the Middle Ages offers a historical overview of the Middle Ages in the area of today's Germany from around 800 to around 1500.

The Carolingian Franconian Empire , which had risen to become the new great power in Europe around 800, split up in the 9th century into West Franconia and East Franconia , the "germ cells" of France and Germany, although no "German identity" developed for a long time afterwards. In Eastern Franconia, the Liudolfinger (Ottonen) rose in the 10th century . They achieved the western " Roman " imperial dignity and laid the foundation for the Roman-German Empire , which had no national, but rather a supranational character. It has also been known as the Holy Roman Empire since the late 13th century and comprised imperial Italy until the early modern period .

The Roman-German kings and emperors saw themselves in the context of translation theory in the tradition of the ancient Roman Empire . Ottonen and the subsequent rulers of the Salians and Staufers based themselves in different ways on the imperial church and made a universal claim to validity with regard to the renewed empire. In the course of the Middle Ages, therefore, there were repeated disputes between the two universal powers, the emperor (imperium) and the papacy (sacerdotium). These conflicts were particularly pronounced during the investiture dispute in the late 11th / early 12th century, in the late Staufer period and then again in the first half of the 14th century.

In the late Staufer period, kingship lost power, as did the empire's influence in Latin Europe. In contrast to the Western European kings of England and France, however, the Roman-German kings did not have too much central power in any case; rather, the aspect of consensual rule in association with the greats of the empire was emphasized. The position of the numerous secular and ecclesiastical rulers in relation to the monarchy was further strengthened in the late Middle Ages , with the electors claiming exclusive royal suffrage from the second half of the 13th century . The Golden Bull of 1356 finally legitimized an electoral monarchy , although from the middle of the 15th century the Habsburgs were the emperors almost continuously until the end of the empire in 1806. In the late Middle Ages, kingship had to rely primarily on its own domestic power policy and could effectively only intervene in the south and partly in the Rhine area.

Early middle ages

Late Carolingian period

Charlemagne (ruled 768 to 814) had greatly expanded the borders of the Franconian Empire , which rose to become a new great power alongside Byzantium and the Abbasid caliphate . It comprised the core part of early medieval Latin Christianity and was the most important state structure in the West since the fall of Western Rome . Karl had ensured effective administration and initiated a comprehensive educational reform, which resulted in a cultural revitalization of the Franconian Empire . The political high point of his life was the coronation of the emperor at Christmas 800. This event created the basis for the western medieval empire .

After Karl's death in January 814, he was succeeded by his son Ludwig the Pious , whom Karl had already crowned co-emperor in 813. The first few years of Ludwig's reign were mainly shaped by his will to reform in the ecclesiastical and secular areas. In 817 Ludwig decided that after his death the empire should be divided. His eldest son Lothar was to be given priority over his other sons Ludwig (in Bavaria) and Pippin (in Aquitaine). A difficult situation arose when, in 829, Emperor Ludwig also assured Karl , his son from his second marriage to Judith , who was influential at court , a share in the inheritance. Soon there was open resistance to the emperor's plans. With the uprising of the three eldest sons against Ludwig the Pious in 830, the time of crisis in the Carolingian Empire began, which eventually led to its dissolution. The rebellion in 833 led to the capture of the emperor on the " Lügenfeld bei Colmar ", whereby Ludwig's army overran to the enemy. Then Ludwig had to agree to a humiliating act of penance. In 834, however, several supporters turned away from Lothar, who withdrew to Italy. While the empire was increasingly besieged from the outside by Vikings , Slavic tribes, and even Arabs, internal tensions persisted. Ludwig the German had secured his position in the eastern part of the empire, like Karl in the west, so that the pressure on Emperor Lothar increased. Karl and Ludwig formed an alliance against Lothar and defeated him in the Battle of Fontenoy on June 25, 841. In February 842 they reaffirmed their alliance with the Strasbourg oaths . At the urging of the Franconian nobles, the Treaty of Verdun was signed in 843 : Charles ruled the west, Ludwig the east, while Lothar was given a middle empire and Italy.

The question about the beginnings of “German” history, which is often discussed in research in this context, is rather misleading, as it was a long-term process that stretched into the 11th century; The name Regnum Teutonicorum can only be proven with certainty from the 10th century . Apparently, however, the Carolingian parts of the empire were becoming more and more separated from each other in the 9th century, and imperial unity could only be restored temporarily.

After Lothar's death in 855, his eldest son Lothar II inherited the Middle Kingdom. After his death in 869, there was a conflict between Karl and Ludwig over the inheritance, which led to the division in the Treaty of Meerssen in 870 . This finally formed the West and East Franconia , while in Italy from 888 to 961 kings ruled separately . Under Charles III. who won the imperial crown in 881 and ruled over all of Eastern Franconia since 882, the entire empire was reunited for a few years when he also acquired the west Franconian royal crown in 885. But this unification of the empire remained an episode. In the “Regensburg continuation” of the annals of Fulda for the year 888 it is disparagingly noted that after the death of Charles (in January 888) many reguli (petty kings) in Europe seized power, with Arnulf , a nephew of Charles III., In Eastern Franconia ruled (ruled 887-899). The collapse of the Carolingian Empire became obvious.

In the east, the last Carolingian Ludwig the child died in 911; he was succeeded by I. Konrad after. Konrad tried to stabilize Eastern Franconia, where he had to assert himself against the powerful nobility and at the same time had to fend off the Hungarians who had founded an empire a few years earlier. After 987, the Capetians came into West Franconia , and they then provided the French kings until the 14th century. West and East Franconia were now finally separate empires.

Time of the Ottonians (Liudolfinger)

After the death of the East Franconian King Konrad in 919, Heinrich I, the first member of the Saxon house of the Liudolfinger ("Ottonen"), ascended the East Franconian royal throne; they were able to hold their own in the empire until 1024. In more recent research, the importance of the Ottonian period for the formation of Eastern Franconia is emphasized, but it is no longer considered the beginning of actual “German” history. The complex process associated with it dragged on at least until the 11th century.

Heinrich I was confronted with numerous problems. The rulership, based on Carolingian patterns, reached its limits, especially since the written form, a decisive administrative factor, was now falling sharply. In relation to the greats of the empire, Heinrich, like several other rulers after him, seems to have practiced a form of consensual rule . Nevertheless, until around the year 1000 Swabia and Bavaria remained regions remote from the kings, in which the influence of kingship was weak. The empire was still in a defensive battle against the Hungarians, with whom an armistice was concluded in 926. Heinrich used the time and had the border security intensified; the king was also successful against the Elbe Slavs and Bohemia. In 932 he refused to pay tribute to the Hungarians; In 933 he defeated them in the battle of Riyadh . In the west, Heinrich had initially given up the claim to Lorraine, which was disputed between West and East Franconia , in 921 before he could win it in 925.

During the reign of Heinrich's son Otto I (r. 936–973), Eastern Franconia was to assume a hegemonic position in Latin Europe. Otto proved to be an energetic ruler, but the exercise of power was not without its problems, because he deviated from his father's consensual rule. At times Otto behaved inconsiderately and came into conflict with close relatives several times. Otto succeeded in organizing a defense against the Hungarians and in 955 defeating them in the battle of the Lechfeld . His reputation in the empire was increased considerably by this success. In the east he won victories over the Slavs, with which the Elbe Slavic areas ( Sclavinia ) were increasingly involved in Ottonian politics. Otto promoted the establishment of the Archdiocese of Magdeburg , which he finally succeeded in 968. The goal was the Slavic mission in the east and the expansion of the East Franconian area of dominion, for which border marks were set up based on the Carolingian model. He was crowned emperor by the Pope on February 2, 962 in Rome, in return he confirmed the rights and possessions of the church. The western empire, based on the ancient Roman imperial dignity, was now connected to the East Franconian (or Roman-German) kingship. In addition, large parts of Upper and Central Italy were annexed to the East Franconian Empire ( Imperial Italy ). Inside Otto, like many early medieval rulers in general, relied primarily on the church for administrative tasks. When Otto died on May 7, 973, after difficult beginnings, the empire was consolidated and the empire once again a political power factor.

Otto's son Otto II (r. 973–983) was crowned co-king in 961 and co-emperor in 967 at a very young age. In April 972 he had married the educated Byzantine princess Theophanu . Otto himself was also educated and, like his wife Theophanu, he was also interested in intellectual matters. In the north he fended off attacks by the Danes, while in Bavaria Heinrich der Zänker (a relative of the emperor) acted unsuccessfully against him. In the west there was fighting with West Franconia (France) before an agreement could be reached in 980. Unlike his father, Otto planned the conquest of southern Italy, where Byzantines, Lombards and Arabs ruled. The campaign began at the end of 981, but in July 982 the imperial army suffered a crushing defeat against the Arabs in the battle of Cape Colonna . Otto managed to escape only with difficulty. In the summer of 983 he planned a new campaign to southern Italy when, under the leadership of the Liutizen, parts of the Elbe Slavs rose up ( Slav uprising of 983 ) and the Ottonian mission and settlement policy suffered a severe setback. The emperor died in Rome on December 7, 983, where he was buried.

He was succeeded by his son of the same name, Otto III. (ruled 983–1002), who had been elected co-king before his father's death when he was not quite three years old. Due to his young age, his mother Theophanu first took over the reign , after her death in 991 until 994 his grandmother Adelheid of Burgundy took over the reign. The ruler, highly educated for his time, surrounded himself over the years with scholars, including Gerbert von Aurillac . Otto was particularly interested in Italy; He intervened several times in Italy and also intervened in the conflict between the papacy and the influential urban Roman circles. In cooperation with the Pope, the emperor strove for church reform and had a great influence on the nominations of the Pope at that time. Otto stayed in Italy for a long time and died there at the end of January 1002.

Successor of Otto III. was Heinrich II (ruled 1002-1024), who came from the Bavarian branch of the Ottonians and whose accession to power was controversial. Henry II set different priorities than his predecessor and concentrated primarily on the exercise of power in the northern part of the empire, although he moved to Italy three times. On his second Italian campaign in 1014, he was crowned emperor in Rome. In the south there were also clashes with the Byzantines in 1021/22, which in the end were unsuccessful and brought the emperor no profit. In the east he led four campaigns against Bolesław of Poland before the Treaty of Bautzen was concluded in 1018 . Inside, Heinrich presented himself as a ruler permeated by the sacred dignity of his office. He founded the diocese of Bamberg and favored the imperial church, whereby royal rule and church in the empire acted closely together. His marriage remained childless, instead of the Ottonians, the Salians came to rule.

High Middle Ages

Salier

Konrad II. And Heinrich III.

In 1024 the German princes elected Salier Konrad II as king. Konrad acquired the Kingdom of Burgundy (later also called Arelat ) in 1032/33 , so that the Roman-German Empire now consisted of three parts of the empire: the northern Alpine (German) part of the empire, imperial Italy and Burgundy. The medieval empire was at the height of its power. Konrad II supported the church reforms and promoted the city of Speyer , which gained special importance under the Salian rulers.

Konrad's son Heinrich III. pursued a similar policy in the ecclesiastical area and intervened in Rome for the benefit of the Pope. At the Synod of Sutri in 1046 he deposed the three rival popes and shortly thereafter also issued a ban on simony . He carried out the investiture of bishops and abbots himself; in general, the imperial church was under Heinrich III. integrated even more strongly into the concept of rule and emphasized the sacred component of royal rule. Heinrich achieved the feudal rule of the empire over Bohemia, Poland and Hungary. Inside, however, oppositional forces formed (as in Lorraine, Saxony and southern Germany) who were dissatisfied with Heinrich's rule. In a sense, Henry's reign seems to have been both the climax and the beginning of a time of crisis in Salian rule.

Investiture dispute

Henry IV ascended the royal throne at a very young age. During his immaturity, several greats took advantage of the political situation in their favor, which caused damage to the royal rule. Heinrich called in Ministeriale and tried to curb the princely influence. However, his intervention in Saxony led to military clashes . Almost at the same time, the so-called investiture dispute escalated .

In 1073 the church reformer Gregory VII became the new pope. Henry IV disregarded the prohibition of lay investiture , so that there was finally a conflict between the empire and the papacy, and several pamphlets emerged in this context. Gregor punished the king with excommunication in 1076, thereby excluding Heinrich from the community of believers. Several German princes now allied against the king. In order to avoid being deposed, Henry IV achieved the solution of the church ban in the famous walk to Canossa in 1077.

The dissatisfaction of several greats with Heinrich's policy remained, however. With Rudolf von Rheinfelden and (after Rudolf's death in battle) with Hermann von Salm , two opposing kings were raised, but Heinrich was able to prevail against both. The conflict between Heinrich and Gregor came to a head again, but Heinrich was able to pull several secular and clerical princes on his side, so that Heinrich's renewed banishment in 1080 remained ineffective. He was crowned emperor in Rome in 1084 and deposed Pope Gregory VII, who died in exile. Heinrich was able to come to an understanding with the Saxons in 1088 and later with other great men, but soon afterwards there were again conflicts in the empire.

His son Heinrich V finally allied himself with the princes against his own father and achieved the deposition of the emperor in 1105. Under Heinrich V, the Worms Concordat in 1122 settled with the church and ended the investiture dispute. However, like his father, Heinrich V was also confronted with several conflicts in the empire. After initially acting in consensus with the greats, Heinrich changed his policy in 1111 and again emphasized royal rule. Heinrich finally saw himself forced to give in, and under princely pressure he returned to consensual rule in 1121.

Staufer

Conrad III.

When Heinrich V, the last Salier, died in 1125, the princes elected the rather weak Saxon Duke Lothar III. from Supplinburg to the king. With that the princes took up their traditional right to vote again. A part of the princes who with the election of Lothar III. did not agree, opted for the Staufer Konrad III. who remained the opposing king until 1135. After Lothar's death in 1138, Conrad III. finally king.

Conrad III. recognized the duchies of Bavaria and Saxony from the Guelph Heinrich the Proud , but the Ascanians employed in Saxony could not assert themselves, so that the son of Heinrich the Proud, Heinrich the Lion , received the Duchy of Saxony again in 1142. There was also fighting in Bavaria. In addition, after the Second Crusade, Konrad became increasingly involved in European foreign policy.

Friedrich I. Barbarossa

Konrad's nephew Friedrich I became the new king in 1152. He sought a cooperation with his cousin, the Guelph and Saxon Duke Heinrich the Lion , who was enfeoffed in 1156 with the Duchy of Bavaria, which was reduced to Austria. In the Treaty of Constance in 1153, a compromise was reached with the Pope, whereby Frederick achieved his imperial coronation in 1155. Friedrich emphasized the Honor Imperii , with which the preservation of imperial rights was connected. He was initially successful in the conflict with the Lombard cities that were striving for more independence . After an uprising he had Milan completely destroyed in 1162 , but the fighting flared up again later.

When Alexander III. When it became Pope and not Viktor IV , who was favored by Friedrich , the struggle for supremacy between emperor and pope began again. Alexander excommunicated Friedrich after Viktor was recognized as legitimate Pope by a pro-imperial body at the Synod of Pavia. In 1166 Frederick I went on his fourth expedition to Italy to enforce the election of Viktor militarily. In 1167 the imperial army conquered Rome , but had to leave the city because of a malaria epidemic . The northern Italian cities then united to form the Lombard League and allied themselves with Alexander III. Before Frederick's fifth campaign in Italy, several princes refused to help him with weapons. In 1176 Frederick I was defeated by the Milanese at Legnano . He had therefore in the Peace of Venice Alexander III. recognize as Pope. In return, he achieved the solution of the ban. The Peace of Constance with the Lombards Union in 1183 forced Friedrich to make several compromises, but the peace treaty also meant an end to the fighting in imperial Italy.

In 1180 Frederick I had the increasingly powerful Heinrich the Lion , who also no longer supported the emperor's Italian policy, ostracized and deprived him of his duchies and his feudal lords in Mecklenburg and Pomerania. The Duchy of Bavaria was given to the Wittelsbachers , Saxony was divided. In 1183, Friedrich made peace with the Lombards, although the Hohenstaufen could not achieve his earlier political goals and had to make a compromise. He was able to achieve the coronation of his son Heinrich with the crown of Lombardy in 1186. From 1187 Friedrich I took over the leadership of the crusader movement . He died in Lesser Armenia in 1190 during the 3rd Crusade .

Henry VI. and the battle for the throne

Friedrich's son Heinrich VI. was married to the Norman princess Konstanze, the heiress of the Kingdom of Sicily, which also included southern Italy. In 1194 Heinrich took possession of the Kingdom of Sicily. The empire thus reached a high point in its expansion. Heinrich also pursued an ambitious Mediterranean policy, but his attempt to transform the empire into a hereditary monarchy failed. When Henry VI. Died of an epidemic in 1197 at the age of 32 , there was a double election in 1198 of the Staufer Philip of Swabia and the Guelph Otto IV.

Pope Innocent III favored Otto, but Philipp managed to isolate him little by little. After the assassination of Philip in 1208, Otto IV finally became king. However, when he laid claim to Sicily, he was banned in 1210. The Pope now supported the Staufer Friedrich, the son of Heinrich VI. The following dispute between Guelphs and Staufers was decided in favor of Frederick II in 1214 by the battle of Bouvines .

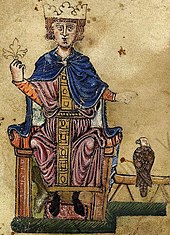

Friedrich II. And the end of the Hohenstaufen

Frederick II ruled his empire from his homeland of Sicily, while the secular and spiritual rulers in the German part of the empire grew stronger. In 1220 Friedrich was crowned emperor. He had his underage son Heinrich elected as Roman-German king, and he left the government there to confidants who exercised the guardianship of Heinrich. He then devoted himself to the stabilization of the Kingdom of Sicily, where he had far more power and an effectively organized state apparatus. Friedrich, who was well educated himself and was also interested in culture, only came to Germany once more when he deposed his son Heinrich in 1235 and had his brother Conrad IV elected.

At the end of the 1220s there was a power struggle between the emperor and Pope Gregory IX. Because of a crusade promise that was not fulfilled quickly enough, the Pope banished the emperor in 1227. Nevertheless, Frederick went to the Holy Land and in 1229 achieved the surrender of Jerusalem without a fight . Back in Italy he successfully fought the papal invasion troops and was finally released from the ban. The tensions remained, however, which finally led to another banishment by Pope Gregory in 1239. The conflict was also carried out with propaganda means and expanded to imperial Italy , where Friedrich tried to enforce his claim to rule over rebellious Lombard cities. The dispute between the emperor and the pope continued when Innocent IV became the new pope. Innocent even declared the emperor deposed in 1245, but Friedrich was able to assert himself. He took military action against the northern Italian cities. However, before a final military decision could be made, Friedrich II died in December 1250. He was to be the last Roman-German emperor for over 60 years.

The Hohenstaufen rule in the German part of the empire was no longer tenable when Frederick died. Conrad IV was able to take over the rule in the Kingdom of Sicily and assert himself there, but he died in 1254. The fight of the Pope with the help of the French Count Karl von Anjou against the Hohenstaufen raged on in the following years, with the Hohenstaufen losing Sicily in 1266. In 1268 the last Staufer, the sixteen year old Konradin , was publicly executed in Naples .

Late Middle Ages

From the interregnum and up to the renewal of the empire

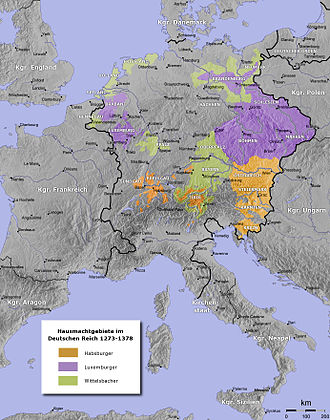

The late Middle Ages (approx. 1250 to 1500) are no longer understood in recent research as a period of decline, in contrast to the older doctrinal opinion . The period up to the late 14th century was strongly influenced by the electoral monarchy: three large families, the Habsburgs , the Luxembourgers and the Wittelsbachers , had the greatest influence in the empire and the greatest domestic power .

After the Hohenstaufen dynasty became extinct, the royal power (though not very pronounced anyway) fell into disuse. During the so-called interregnum from 1250 to 1273, several kings ruled the empire at the same time, but none of them could prevail throughout the empire. One consequence of this was the further weakening of the Roman-German kingdom. The late medieval monarchy could only rely on a reduced imperial property (also due to the increase in imperial pledges , especially in the 14th century). To secure power, the following kings had to try to expand their own domestic power ( domestic power policy ). The sovereigns, on the other hand, continued to gain strength and enjoyed a relatively strong position vis-à-vis royalty. From the second half of the 13th century, the electors had exclusive royal suffrage; When choosing a king, they made sure that the new king respected their rights and claims. In addition, some foreign European powers tried to influence German politics by electing a king (especially the Kingdom of France , for example in 1272/73 and 1308).

The interregnum was ended in 1273 by Rudolf von Habsburg . With the acquisition of Austria, Styria and Carniola, Rudolf paved the way for the House of Habsburg to become one of the most powerful dynasties in the empire. He also succeeded in a certain consolidation of the royal power without, however, being able to restrict the political claims of the electors. The remaining imperial property was ordered and partly re-claimed, Rudolf also set up the bailiffs . Despite intensive negotiations with the papacy, he did not succeed in winning the imperial crown.

Rudolf's successors, Adolf von Nassau and Albrecht I , were in conflict with the elector, who claimed political participation. Adolf von Nassau tried to gain a foothold in Thuringia without much success. His policy ultimately led to his dismissal on the part of the electors; Adolf's attempt to reverse this decision ended with his death in the Battle of Göllheim in 1298. But his successor Albrecht I, a son of Rudolf von Habsburg, did not have a good relationship with the imperial princes, especially the Rhenish electors. His home power policy in Central Germany and his rapprochement with France were a thorn in their side. Albrecht was able to assert himself in combat, but was killed on May 1, 1308 by a family member.

In 1308, Heinrich VII of Luxembourg was elected king. He maintained a good relationship with the electors, one of whom was his younger brother Baldwin von Trier , one of the most important imperial politicians of the late Middle Ages. Heinrich was able to expand his power to include Bohemia in 1310 and was crowned imperial in 1312. Heinrich tried one last time to renew the empire, but he died in August 1313. In Germany he had braced against the expansion of France and achieved a rare harmony of the great houses.

Time of Ludwig of Bavaria and Charles IV.

In 1314, after the death of Henry VII, there was a double election, but Ludwig the Bavarian from Wittelsbach prevailed as successor against Friedrich the Handsome from the House of Habsburg. However, Ludwig soon found himself in a serious conflict with the Pope, who refused Ludwig the license to practice medicine. In 1338, however, the Rhense Kurverein rejected the request for the Pope to confirm the election of the king. The imperial coronation in 1328 had to take place without the Pope as coronator. Successful in his house power policy, Ludwig acquired the Mark Brandenburg , Tyrol , Holland , Zeeland and Hainaut for the House of Wittelsbach. In the empire, however, an electoral opposition to Ludwig formed, which was led by the Luxembourgers . In 1346, Karl IV , the grandson of Henry VII, from Luxembourg , was elected king. However, there was no longer a confrontation with Ludwig because he died soon afterwards.

Charles IV, who is considered the most important Roman-German ruler of the late Middle Ages, relocated his main rulership to Bohemia, the center of his domestic power. During his long reign (1346-1378), Karl gained, among other things, the Margraviate of Brandenburg and Lusatia to his home power complex. In fact, Karl founded a kingship that practiced almost exclusively domestic power politics. In doing so he gave up some imperial claims and pledged large parts of the imperial property that was still available. In this way each successive king was dependent on his own household; Karl assumed that this would benefit his house the most, but ultimately miscalculated.

In 1348 the first German-speaking university in the Holy Roman Empire was founded in Prague . In 1355 Charles was crowned emperor, but he avoided renewing the Italian policy of his predecessors. On the other hand, he partly gave up imperial rights (also in the West), his policy during the Jewish pogroms was also problematic, as he did not intervene sufficiently to protect them (which he was obliged to do within the framework of the Judenregal ) and partly even benefited from the expropriation of Jewish goods (around 1349 in Nuremberg ). The golden bull of 1356 was of particular importance ; it represented a kind of basic law until the end of the Holy Roman Empire.

In the 14th century, overpopulation, bad harvests and natural disasters led to famine. In 1349/50 around a third of the population died of the plague , plus pogroms against the Jews. The late medieval agricultural crisis triggered a rural exodus . It took about 100 years for the population to return to pre-plague levels. Nevertheless, the late Middle Ages were by no means a period of decline or decline, as the cities and trade with the expanding Hanseatic League flourished during this period , as well as fundamental political structures that had a formative effect on the empire in the period that followed.

15th century

Under the successor of Charles, the royal power finally declined. Wenzel , who completely neglected the business of government, was deposed by the four Rhenish princes in 1400. Even his successor Ruprecht , who did not have sufficient funds, could not stop this decline.

In 1411 Sigismund , also a son of Charles and already King of Hungary, became the new king. Sigismund achieved the imperial coronation in 1433, but was unable to stabilize the kingship and reverse the process of decay. An attempted imperial reform fails due to the resistance of the sovereigns. However, by convening the Council of Constance , he was able to end the Western Schism , which was a great success for Sigismund, who was an educated and intelligent king. However, the conviction and execution of Jan Hus led to ongoing wars against the Hussites .

With the death of Sigismund, the house of Luxembourg became extinct in the male line. The Habsburgs succeeded them and from then on provided the Roman-German kings. But neither Albrecht II nor Friedrich III. who acted phlegmatic at times and had more of his possessions than the Reich in mind, were able to carry out an imperial reform. However, the empire went through a structural and constitutional change, whereby in a process of “designed compression” ( Peter Moraw ) the relationships between the members of the empire and the kingship became closer.

Frederick's son Maximilian I won parts of the Burgundian inheritance for the House of Habsburg, although this was the beginning of a long conflict with France that was also fought in Northern Italy. Because of the Turkish wars and the fight against France, Maximilian was dependent on the support of the imperial estates. In 1495 an imperial reform was decided at the Worms Reichstag . Maximilian accepted the title of emperor in 1508 without a papal coronation, thus ending the period of the coronation procession of Roman-German kings to Rome. His marriage policy secured the Habsburgs Bohemia and Hungary and the Spanish crown. It was a turning point. Habsburg rose to a world power under Charles V , the Middle Ages came to an end.

See also

- History of Germany , entire German history

- Germany in modern times

swell

- Rainer A. Müller (Hrsg.): German history in sources and representation. Vol. 1-2, Reclam, Stuttgart 1995-2000.

- Freiherr vom Stein memorial edition . Series A: Selected sources on German history in the Middle Ages. Volume 1 ff., Scientific Book Society, Darmstadt 1955 ff.

literature

- Dieter Berg : Germany and its neighbors, 1200–1500 . Munich 1997 ( Encyclopedia of German History 40).

- Johannes Fried : The way into history. The origins of Germany up to 1024. Propylaea, Berlin 1994 (ND 1998), ISBN 3-549-05811-X .

- Hans-Werner Goetz : Europe in the early Middle Ages . Handbook of the History of Europe, Vol. 2. Stuttgart 2003.

- Herbert Grundmann (Ed.): Gebhardt. Handbook of German History . 9th edition, as a paperback edition, volumes 1–7, Stuttgart 1970 ff. (Revision not yet completed.)

- Alfred Haverkamp: departure and design. Germany 1056-1273 . New German History 2. 2. revised. Beck, Munich 1993.

- Hagen Keller : Between regional boundaries and a universal horizon. Germany in the empire of the Salians and Staufers 1024–1250. Propylaea, Berlin 1986, ISBN 3-549-05812-8 .

- Peter Moraw : From an open constitution to structured condensation. The empire in the late Middle Ages 1250 to 1490. Propylaeen, Berlin 1985, ISBN 3-549-05813-6 .

- Malte Prietzel : The Holy Roman Empire in the late Middle Ages . Scientific Book Society, Darmstadt 2004 (compact history).

- Friedrich Prinz : Basics and Beginnings. Germany until 1056 . New German History 1st 2nd reviewed edition Beck, Munich 1993.

- Bernd Schneidmüller , Stefan Weinfurter (ed.): The German rulers of the Middle Ages. Beck, Munich 2003, ISBN 3-406-50958-4 .

- Bernd Schneidmüller, Stefan Weinfurter (Ed.): Holy - Roman - German. The empire in medieval Europe. International conference for the 29th exhibition of the Council of Europe and state exhibition Saxony-Anhalt. Sandstein-Verlag, Dresden 2006.

- Stefan Weinfurter: The Empire in the Middle Ages: From the Franks to the Germans . Beck, Munich 2008.

Remarks

- ↑ On Karl and his time see for example Johannes Fried: Karl der Grosse. Munich 2013; Dieter Hägermann : Charlemagne. Ruler of the west . Berlin 2000; Wilfried Hartmann : Charlemagne . Stuttgart 2010; Rosamond McKitterick : Charlemagne. The Formation of a European Identity . Cambridge 2008 (German Charlemagne , Darmstadt 2008); Stefan Weinfurter : Charlemagne. The holy barbarian. Munich 2013.

- ^ Egon Boshof : Ludwig the Pious . Darmstadt 1996; Mayke de Jong: The Penitential State. Authority and Atonement in the Age of Louis the Pious, 814-840 . Cambridge 2009.

- ^ Egon Boshof: Ludwig the Pious . Darmstadt 1996, p. 108ff.

- ↑ See for example Johannes Fried: The way in the story. The origins of Germany up to 1024. Berlin 1994, p. 366ff .; Pierre Riché: The Carolingians. One family makes Europe. Stuttgart 1987, pp. 195ff .; Rudolf Schieffer: The time of the Carolingian empire (714-887) . Stuttgart 2005, p. 136ff .; Rudolf Schieffer: The Carolingians. 4th edition, Stuttgart 2006, pp. 139ff.

- ↑ On Ludwig see Eric J. Goldberg: Struggle for Empire. Kingship and Conflict under Louis the German. 817-876 . Ithaca 2006; Wilfried Hartmann: Ludwig the German . Darmstadt 2002.

- ↑ At this time see also Carlrichard Brühl : The birth of two peoples. Germans and French (9th-11th centuries) . Cologne u. a. 2001, p. 115ff. Much more detailed on the development of the two Franconian partial kingdoms after 843 is Carlrichard Brühl: Germany - France. The birth of two peoples . 2nd edition, Cologne / Vienna 1995.

- ↑ Cf. Carlrichard Brühl: The birth of two peoples. Cologne u. a. 2001, p. 69ff.

- ↑ Simon MacLean: Kingship and Politics in the Late Ninth Century: Charles the Fat and the End of the Carolingian Empire . Cambridge 2003.

- ↑ For the following in general see Gerd Althoff: Die Ottonen. Royal rule without a state . 2nd edition, Stuttgart a. a. 2005; Helmut Beumann : The Ottonians . 5th edition Stuttgart u. a. 2000; Hagen Keller, Gerd Althoff: Late antiquity to the end of the Middle Ages. The time of the late Carolingians and Ottonians. Crises and Consolidations 888–1024. 10th edition, Stuttgart 2008.

- ↑ On the classification of Ottonian history in general Hagen Keller, Gerd Althoff: The time of the late Carolingians and the Ottonians . Stuttgart 2008, p. 18ff.

- ↑ For the different research approaches see Joachim Ehlers: The emergence of the German Empire . 4th edition, Munich 2012; see. generally also Johannes Fried: The way into history . Berlin 1994, especially p. 9ff. and p. 853ff. Carlrichard Brühl is fundamental: Germany - France. The birth of two peoples . 2nd edition Cologne / Vienna 1995.

- ↑ For general information on Heinrich's reign, see now Wolfgang Giese : Heinrich I. Founder of Ottonian rule . Darmstadt 2008.

- ^ In addition to the general literature on the Ottonians mentioned, see Matthias Becher: Otto der Große. Emperor and Empire . Munich 2012; Johannes Laudage : Otto the Great (912–973). A biography . Regensburg 2001.

- ↑ Johannes Laudage: Otto the Great . Regensburg 2001, p. 110ff.

- ↑ On this aspect, see Hartmut Leppin , Bernd Schneidmüller , Stefan Weinfurter (eds.): Kaisertum in the first millennium. Regensburg 2012.

- ↑ See in summary Hagen Keller, Gerd Althoff: The time of the late Carolingians and the Ottonians. Stuttgart 2008, p. 239ff.

- ↑ General overview in Hagen Keller, Gerd Althoff: The time of the late Carolingians and the Ottonians . Stuttgart 2008, p. 273ff. See also Gerd Althoff: Otto III. Darmstadt 1997; Ekkehard Eickhoff : Theophanu and the King. Otto III. and his world. Stuttgart 1996; Ekkehard Eickhoff: Emperor Otto III. The first millennium and the development of Europe. 2nd edition, Stuttgart 2000.

- ^ Stefan Weinfurter: Heinrich II. (1002-1024). Rulers at the end of time. 3rd edition, Regensburg 2002.

- ^ Knut Görich: A turning point in the east: Heinrich II. And Boleslaw Chrobry . In: Bernd Schneidmüller, Stefan Weinfurter (Ed.): Otto III. - Heinrich II. A turning point? . Sigmaringen 1997, pp. 95-167.

- ↑ Basic overview in Egon Boshof : The Salians . 5th edition, Stuttgart 2008; see. also Stefan Weinfurter : The Century of the Salians 1024–1125: Emperor or Pope? Ostfildern 2004. On Konrad, see for example Franz-Reiner Erkens : Konrad II. (Around 990-1039). Rule and empire of the first Salier emperor. Regensburg 1998; Herwig Wolfram : Konrad II. 990-1039. Munich 2000.

- ^ Daniel Ziemann: Heinrich III. Crisis or climax of the Salic kingship? In: Tilman Struve (Ed.): The Salians, the Reich and the Lower Rhine. Cologne u. a. 2008, pp. 13-46.

- ^ Gerd Althoff: Heinrich IV. Darmstadt 2006.

- ^ Stefan Weinfurter: Canossa. The disenchantment of the world. Munich 2006; The theses of Johannes Fried ( Canossa: Unmasking a legend. A polemic. Berlin 2012) were discussed very controversially and largely rejected .

- ^ Knut Görich: Friedrich Barbarossa. A biography. Munich 2011.

- ↑ Peter Csendes : Heinrich VI. Darmstadt 1993.

- ↑ Wolfgang Stürner is fundamental: Friedrich II. 2 vol. Darmstadt 1992–2000.

- ↑ Peter Moraw : From an open constitution to a structured compression. The empire in the late Middle Ages 1250 to 1490. Berlin 1985; Malte Prietzel : The Holy Roman Empire in the late Middle Ages. Darmstadt 2004.

- ↑ Bernd Schneidmüller: Consensus - Territorialization - Self-interest. How to deal with late medieval history. In: Frühmittelalterliche Studien 39, 2005, pp. 225–246.

- ^ Martin Kaufhold : German Interregnum and European Politics. Conflict resolution and decision-making structures 1230–1280 . Hanover 2000.

- ^ Karl-Friedrich Krieger: Rudolf von Habsburg. Darmstadt 2003.

- ↑ Peter Moraw: From an open constitution to a structured compression. The empire in the late Middle Ages 1250 to 1490. Berlin 1985.

- ^ Hermann Wiesflecker : Emperor Maximilian I. 5 volumes. Munich 1971–1986; Manfred Hollegger: Maximilian I, 1459–1519, ruler and man of a turning point. Stuttgart 2005.