Swabian dialects

| Swabian | ||

|---|---|---|

|

Spoken in |

|

|

| speaker | 820,000 | |

| Linguistic classification |

||

| Official status | ||

| Official language in | - | |

| Language codes | ||

| ISO 639 -1 |

- |

|

| ISO 639 -2 |

- |

|

| ISO 639-3 |

swg |

|

Swabian is a dialect group that is spoken in the middle and south-east of Baden-Württemberg , in south-west Bavaria and in the far north-west of Tyrol .

From a linguistic point of view, Swabian belongs to the Swabian-Alemannic dialects and thus to Upper German . It has separated itself from the other Swabian-Alemannic dialects through the complete implementation of the New High German diphthongization . “My new house” is therefore “Mae nuis Hous” in Swabian (depending on the region) and not “Miis nüü Huus” as in other Alemannic dialects .

In terms of area typology , Swabian is comparatively isolated within the Upper German area as a whole, but at the same time (unlike the neighboring East Upper German Central Bavarian ) internally very heterogeneous.

Dialect spaces and distribution

The Inner Swabian dialect areas are conventionally divided into West, Central and East Swabian. The boundaries of these three regions are drawn slightly differently. As a first rough approximation, West Swabian and Central Swabian are in Baden-Württemberg , East Swabian in the Bavarian administrative district of Swabia .

Middle Swabian (also: Neckarschwäbisch, Niederschwäbisch) is spoken in the densely populated areas of Stuttgart / Ludwigsburg, Böblingen / Sindelfingen, Tübingen / Reutlingen, Esslingen am Neckar, Kirchheim / Nürtingen, Waiblingen / Backnang and Göppingen, including the neighboring areas of the northern Northern Black Forest in the west and the Swabian Alb in the south, provided that the New High German has not yet intervened. The key word for Middle Swabian can be gwäa ' Been ', as well as the oe sound such as B. in noe 'no', Boe 'leg', Schdoe 'stone'.

West Swabian or Southwest Swabian (because in the western and northwestern border area with Calw and Pforzheim the Central Swabian without West Swabian share directly borders the South West Franconian) has the above-mentioned sound as a characteristic , e.g. B. Boa Bein ', noa ' no ', Schdoa ' Stein 'etc. The southwest Swabian area begins with a very narrow strip of individual villages southwest of Calw and becomes wider and wider further south. It includes the areas of Rottenburg, Freudenstadt, Horb, Sulz, Hechingen, Balingen, Albstadt and Sigmaringen. Starting in the north with 'gwäa', towards the south from Horb gsae the gwäa 'was' replaced. From Horb onwards there is a characteristic singsong in the speech melody, which is most evident in Balingen and Albstadt. Further south (from Sigmaringen), the southwest Swabian language changes into Lake Constance Alemannic.

East Swabian is spoken in the Wuerttemberg areas of Aalen, Heidenheim and Ulm, as well as in almost all of the Bavarian administrative district of Swabia , from Nördlingen in the north to Augsburg in the center and into the Allgäu in the south. The eastern border to the Bavarian is largely the Lech . As Leitvokal of Ostschwäbischen the diphthong 'oa', in place of the central and western Swabian monophthong å apply: Schloaf instead sleep 'sleep', Schdroas instead Schdrås 'street', etc.

The much-cited Älblerisch as a separate dialect space does not exist in linguistic terms. It is an invention of Swabian joke and joke literature. By far the largest area of the Swabian Alb (Reutlinger, Uracher, Münsinger, Laichinger, Nürtinger, Kirchheimer, Göppinger Alb) belongs to the Central Swabian region. The significantly smaller area of the south-west Alb (Balingen, Albstadt and parts of the Großer Heuberg) belongs to the south-west Swabian region. The only difference to the lower-lying areas of the two dialect areas is the somewhat less advanced Verneu High German.

Within the three main rooms mentioned, further dialects are repeatedly postulated, mostly out of local interest: However, they do not constitute further dialect areas, but remain subordinate to the three larger areas. Examples of this:

- Enztalschwäbisch (sometimes also called Enztalfränkisch ), spoken in the upper Enztal south of Pforzheim and in the lower Nagoldtal from Calw to the north. It is an originally Franconian settlement area that has been strongly reshaped in Swabia. The Franconian origin is still exemplified in formulations like i haa gsaa (pure Central Swabian would be i hao gsaed ) 'I said'. Assignment: Main area Central Swabian. The old historical borderline between Swabian and Franconian dialect in this area can be found with Karl Bohnenberger.

- Giant Swabian . The Rieser doesn't say do hanna, but do dranna when he means 'there there'. Assignment: Main area East Swabian.

- Allgäu (Tyrolean Swabian) in the districts of Upper and Eastern Allgäu , also used in neighboring areas of Tyrol (Lechtal, Ausserfern), Vorarlberg and Upper Bavaria (Lechrain). Assignment: Main area East Swabian.

- Transitions to Bavarian : In the district of Aichach-Friedberg , Bavarian is sometimes spoken, but with a strong Swabian influence. With Lechrainian there is a transition dialect based on East Swabian to Bavarian, which is widespread in the Upper Bavarian districts of Landsberg and Weilheim-Schongau . Assignment: Main area East Swabian.

Phonological features

The sound stock of Swabian, especially vowels, is much richer than that of today's standard German . It comprises considerably more monophthongs and diphthongs , plus a considerable number of nasal sounds and schwa sounds, which go far beyond the comparatively small inventory of the standard German language. Therein lies the basic problem of every kind of spelling in Swabian: "The 26 letters of our Latin alphabet are insufficient in front and in the back to reflect the richness of Swabian vocalism". In order to do justice to the peculiarity of Swabian, it first seems to be necessary to grasp it empirically as a language of its own. Only then can it be compared appropriately with today's German.

Vowels in stem syllables

From an empirical point of view, the Swabian language has a total of seven basic vowels: a, e [e], ä [ɛ], i, o, u, å [ɑ̃ː] (in Swabian Fråg “question” etc.). They can all be combined with the vowels a, e, and o to form diphthongs.

Some of the basic vowels have a large number of realizations ( allophones ). For example, the a has at least the following allophones:

- [a] (or strictly according to IPA [ä]), the unrounded open central vowel , in its short form, as in sack;

- [aː], the long variant, as in Bad;

- [ɐ] or [ɜ], the almost open central vowel or unrounded half-open central vowel , in its short form, as in the ending -en z. B. in lift [ˈheːbɐ], in the plural of -le -reduction z B. in Mädle ['mɛːdlɐ], or with many speakers before [m], [n] and [ŋ] z. B. in Lamm ['lɐm], Anna [' ɐnaː] or Hang ['hɐŋ];

- [ɐː], the long variant, with many speakers before [m], [n] and [ŋ], as in came ['kɐːm] or Kahn [' kɐːn]; with some speakers also Bahn [bɐː] or Mann [mɐː] (central variant);

- [ɐ̃ː], as in Bahn [bɐ̃ː] or Mann [mɐ̃ː] with some speakers (central, nasal variant);

- [ɑ̃ː] or [ɔ̃ː], as in Bahn [bɑ̃ː] or Mann [mɑ̃ː] with some older speakers (rear, nasal variant);

- [ɑː] or [ɔː], as in Bahn [bɔː] or Mann [mɔː] with most of the younger speakers (back variant).

Within diphthongs, the allophones [a] and [ɐ] can become actual phonemes; H. Sounds that have different meanings:

- In combination with [e] or [i], the supra-regional "Halbmundart" and certain regional dialects contain the phonemes [ae] and [ɐi], such as in into [nae] and new [nɐi] (basic dialect [nʊi]) or in trees [baem] (mostly dialectal [beːm]) and with [bɐim]. A High German spoken by a Swabian speaker also knows the distinctions like body [lɐib] and Laib [laeb] (in Swabian, however, [lɔeb]) or color white [vɐis] and I know [vaes] (in Swabian, however, [vɔes]).

- In combination with [u] and [o] phonemes [ao] and [ɐu], as there are deaf [taob] and dove [tɐub] or he hits [haot] and skin [hɐut].

Umlauts

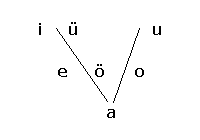

The standard German language knows three umlauts : a / ä, o / ö, u / ü . These three umlauts hardly appear in the Swabian language. The vowel ä is very precisely distinguished from the vowel e in Swabian and is usually used as an independent basic vowel . Only in a few exceptional cases does it serve as an umlaut for a . The vowels ö and ü of Standard German correspond to the sound level of Middle High German; in Swabian (as in most of the other Upper and Central German dialects) they were rounded off to e and i , cf. standard German singular oven / plural ovens = Swabian singular Ofa / plural Efa and standard German Fuß / Fuß = Swabian Fuaß / Fiaß .

Diphthongs

The number of diphthongs is considerably higher than in standard German and is a total of 15. In the course of the development of Swabian, similar to the development of standard German, both Middle High German monophthongs and already existing diphthongs were further developed, but the latter almost always in other Direction than in standard German. The development processes of the diphthongs and their results are so complicated in Swabian that reference must be made to the specialist literature for details. For the sake of clarity, only a few details can be listed here:

- The Middle High German long ī [iː] was pronounced ei, [aɪ] in Standard German . Example: Middle High German zīt and wīb correspond to standard German time and woman . In Swabian this old long ī was also diphthongized, but only lowered to [əi] or [ɐi]. Only the Middle High German diphthong ei [ei] was lowered to [ae] in Swabian. This leaves a number of semantic differentiations that no longer exist in standard German. For example, the Schwabe different in pronunciation clearly between body [lɐib] and loaf [Läb] Since (Page) [sɐit] and Sait (string) [sows], etc. Since the difference between [ɐi] from MHG. Ī and [ ae] or [ɔe] from mhd. ei can mark a difference in meaning, they are real phonemes and not just allophonic pronunciation differences . Due to the enormous variety of vowels and diphthongs, Swabian is one of the languages with the greatest number of phonemes, which enables very concise yet semantically precise word and sentence formation.

- The same applies to the Middle High German long ū [uː], which in Swabian was diphthongized to [əu] or more precisely [ɐʊ]; only the Middle High German diphthong ou was lowered to [ao] in Swabian, which, unlike in standard German, did not coincide in Swabian either. This difference is also phonematic in Swabian, the Swabian clearly distinguishes between pigeons (= birds ) in pronunciation . [dɐʊbɐ] and deaf (= deaf ). [daobɐ]. With some words it stays with u, namely when the Middle High German long ū was shortened before the beginning of the diphthongization, e.g. B. ufschraibe [ʊfʃrɐibɐ] (write down).

- Where the long Middle High German long ū comes before n or m , for example in zūn = fence, the diphthongization is complete, so the pronunciation is [tsaon] and not [tsɐʊn]. The same applies before mhd. Ī before n or m, such as in mīn (mein), wīn (wine) and līm (glue): In Swabian it was first diphthongized and lowered to [ai] as in standard German and later in large parts of Swabia further developed to [oi], [õi] or [ɑ̃i], thus to moi [moi / mõi / mɑ̃i] and Woi [voi / või / vɑ̃i]. In the dialect continuum to the Alemannic language area, the long Middle High German ī was partially retained as a short i , e.g. B. [min] instead of [moi / mõi / mɑ̃i]. In recent times these sounds are often articulated again by Swabians as [ae] due to the pressure of Standard German, while Middle High German ī continues to be articulated as [əi], for example mae Zəendung [maɛ̃ t͡seleid] instead of traditional Swabian moi Zəidong [moi / mõi / mɑ̃i t͡seendung] or mi Zeleid [mi t͡seendung] (my newspaper). The traditional Swabian difference in the diphthong is retained because the standard German pronunciation maene Zaetung still sounds extremely affected even in the ears of strongly assimilated Swabians.

- Middle High German / iə / is Swabian as [iɐ]: schiaf [ʃiɐv̊] "crooked" and - via rounding off from / yə / - miad [miɐd] "tired". However, these old diphthongs are on the decline.

- The Swabian diphthong ui sounds rather unusual for standard German ears (cf. at least the interjection pfui ) , for example in nui "new" [nʊi].

- Almost all diphthongs in Swabian can also be nasalized (which makes pronunciation of Swabian even more complicated for non-Swabians). After all, the differentiated Swabian nasalizations are almost always only allophonic, so - in contrast to the highly differentiated vowelism of Swabian - they mark no differences in meaning. Example: Swabian ãẽkaofa [æɛ̃ɡaofɛ̃] "to buy", since here the n is broken up by nasalization in the diphthong.

Nasal sounds

A characteristic of Swabian is its somewhat nasal sound, because many vowels are nasalized in Swabian. Vowels before the m, n and ng sounds are generally (slightly) nasalized, even if they are short, or at least they are articulated a little less clearly. According to international usage, nasal vowels are written with a tilde : ã, ẽ, õ , etc. Such nasal sounds are particularly common in Portuguese . Swabians have fewer problems pronouncing French correctly than other German students , as they are at least approximately familiar with the four nasals of French.

Vowels in sub-syllables

In contrast to New High German, Swabian does not know the middle central vowel known as the Schwa- Laut . In NHG it comes mainly in the infinitive -en before (reading, writing, arithmetic) before. For the infinitive -en as well as the plural of diminutive -le is in Schwäbischen the almost open central vowel [ɐ] (or almost identical, the unrounded half-open central vowel [ɜ]), partially also its nasalized variant [ɐ], used , but sometimes only a very short unrounded open central vowel [ă]; for example, will raise as [heːbɐ] or [HHBA], the plural of Mädle pronounced as [ 'mɛːdlɐ] or [' mɛːdlă].

Some authors speak of "light vowels" in this context: Swabian knows, beyond New High German, not only short or long versions of vowels, but also three only extremely lightly pronounced versions of the vowels "closed e" [ě], "short, nasalized a "[ă] and" closed o "[ǒ]. These "light vowels" are barely recognizable to High German ears.

Of greater importance is the distinction between the two light vowels [e] and [ă] for the singular and plural of the diminutive, e.g. B. Mädle ['mɛːdlě] = singular and Mädla [' mɛːdlă] = plural.

The light vowel ǒ always occurs where New High German writes an e before r . This concerns z. B. the definite article masculine singular the . It is spoken in Swabian dor [dǒr]. In this case, the ǒ is so easy that many dialect authors only write dr .

Consonants

a) k, p and t sounds: These three Fortis sounds are generally pronounced in Swabian as soft Lenis sounds: b, d and g . [b ɡ d]. A similar weakening is widespread in many areas of Germany as the so-called internal German consonant weakening . Examples: Schdual instead of a chair and Dabeda [dabedɛ̃] instead of wallpaper . In the south of the Swabian-speaking area, however, the weakening is not so advanced and usually only affects the initial sound: Dag instead of German, day, but ceiling instead of Degge as in the north . Final hardening , on the other hand, is alien to Swabian; In contrast to the standard language, the final -d is retained, for example in Rad or Wind , and does not become a -t .

b) r-sounds: With many speakers, the sound of the r-sound differs from the uvular pronunciation [ ʁ ], the uvula-R, which occurs most frequently in standard German . The sound velar is spoken ([ ɣ ]). This r sounds similar to a ch as in the word Da ch , which is breathed out. At the end of the syllable, e.g. B. with wied he or Wengert he , and before dental-alveolar consonants (in German d, n, s and l), z. B. in the word E r de, the r is spoken particularly deep in the throat ( pharyngal , [ ʕ ]), this r sounds very similar to a nasalized A (å).

c) s-sounds: Like other southern German dialects, Swabian only knows the voiceless s; There is no voiced s that has penetrated the standard German language from Low German (e.g. in rose or at the beginning of a word). The special designation of a voiceless s with the letter <ß> is therefore superfluous in Swabian.

d) sch-Laut: This sound occurs much more frequently in Swabian than in German, almost always before d / t and b / p, even inside a word. So z. B. Raspel and Angst in Swabian pronounced as Raschbl and Angschd . In Swabian it tends to be more in the back of the tongue, in German it tends to be in the front of the tongue. At the very eastern edge of Swabian, the sch sound is also used before g / k , e.g. B. Bruschtmuschkel for chest muscle . The sound sequence "st" was added to / scht / in all positions in the German southwest including Switzerland and Alsace around the 11th century. The sound sequence / st / is therefore generally very rare in Swabian, but it does occur, especially in verb forms of the 3rd person singular like he thinks / he hates or s (i) e reads “he is called”, “she leaves”. This is explained by the fact that at the time of the development from st to scht these verb forms were still two-syllable ("he is called") and only later did the schwa in the second syllable disappear. For the same reason, true Swabians also hear the weekday designation Samsdag (from mhd. Saturday, written sameztac !) Next to the more frequent Samschdag, in which the change was reproduced in a secondary and analogous way (no Swabian would say Saturday ). However, in parts of Swabia the weekday is not called Samschdag, but Samschdig. This already seems to be a further development due to the ongoing German phonetic shift.

As a verbal ending of the 2nd person singular (in modern Swabian -sch , in classic Swabian -scht ) this sound is one of the classic features of all Swabian speakers: you musch (t), you write (t) etc., but occurs also in other dialects.

Other features

- The standard language endings “-eln” and “-ern” (in “Würfeln”, “moan”) are -lâ and -râ in Swabian : wirflâ, mäggrâ .

- "Man" is in the Swabian mā or mr spoken

- The personal pronoun of the 1st person Pl. Nom. Is me (German "we"). This sound, which is widespread in German dialects, originated in the inverted sentence position “have we”, in which the initial “w-” was assimilated to the preceding verbal ending “-en” .

- Different cases for certain verbs, e.g. B. Dative instead of accusative : I leit dr aa (I'll call you).

- Verbs that are reflexive in standard German are used in Swabian e.g. T. replaced by non-reflexive descriptions: sit, lie down, stand up will nâsitzâ (sitting down), nâliegâ (hinliegen) nâschdandâ (hinstehen) z. B. D'kansch dahannâ nâsitzâ (you can sit here). Swabians who speak the standard language often continue to use these forms in the standard German sound, which seems a bit strange in northern Germany.

- where as an always unchangeable relative particle instead of "the, the, that, which, which, which": Dui Frao, må (also the må ) i ân kiss gäbâ hann, ..., also gea hao, ... "The woman whom I kiss have given ... "

- The times vierdl (three) and dreivierdl (fenfe / feife) mean "quarter past ... (two)" and "quarter to ... (five)" in other language regions. This way of speaking occurs (or occurred) in other regions too, e.g. B. in Berlin , Saxony and Saxony-Anhalt .

- Numbers:

|

- Note on the number 1: The Swabian language distinguishes between the indefinite article and the numeral: The indefinite article reads a, while the numeral is oe [like English a and one ]. E.g. a Mã, a woman, a Kend (generally a man, a woman, a child) and oe Mã, oe woman, oe Kend (1 man, 1 woman, 1 child). The German language can only express this difference through different intonations.

- Note on number 2: Regional differentiation is made according to gender : Zwee Manne, zwoa / zwo Fraoa, twoe Kend (or) (2 men, 2 women, 2 children).

- Note on number 3: The time is em drui (at three o'clock).

- Examples of further numbers: Oisazwanzg (21), Zwoiazwanzg (22), Simnazwanzg (27), Dausedzwoihondrdviirädraißg (1234)

- The particular word ge is used to express an activity to which one goes directly (originated from “gen”, which in turn originated from “against”). For example i gang ge schaffa (I go to work) or me goant ge metzga (we go to slaughter).

- Southwest Swabian has other peculiarities: The subjunctive I for the reproduction of a verbatim speech is used very often compared to the spoken standard German (e.g. she hot gsait sie komm am eighth for “she said she would come at 8 o'clock”). In contrast to standard German, it also has an auxiliary subjunctive I: därâ (e.g. Se hond gsait se därât am neine kommâ for "You said you would come at 9 o'clock"). Likewise, “have” with häbâ has its own subjunctive I-form (e.g. Se hond gsait se häbât koâ time for “You said you had no time”). Thus, the subjunctive can be clearly distinguished from the subjunctive II (Se hettât koâ time when ...; Se dätât am neine come when ...) .

- When comparing, instead of the standard language “as” the “how” (“I am taller than you”) or even the combination “as like” (“I am taller than you”) is used.

Grammatical Features

vocabulary

False friends

The term false friends is used for words from different languages that are written or aurally similar, but each have a different meaning. Wrong friends easily lead to translation errors. There are also numerous false friends in the relationship between German and Swabian . A well-known example are the German / Swabian word pairs heben / heba and hold / halda . To hold German corresponds to Swabian not halda , but heba ; German lift corresponds schwäbisch not heba, but lubfa .

The following list contains further examples of German / Swabian "false friends":

- For body parts: the leg up to the thigh is referred to as the “foot”, the “Kreiz” (back) encompasses the entire back; In extremely rare cases, the hand, forearm, elbow and upper arm up to the shoulder joint are also referred to as the “hand”, and the “belly” encompasses the entire body. A Swabian is able to get a cramp at the point "where the foot joins the stomach" (or also: "I han en wadâkrampf em Fuaß").

- for animals: a housefly (Musca domestica) is called in Swabian "Mugg" (or also "Fluig"), a mosquito (Culicidae) is called "Schnôg" (Schnake); for the mosquito family (not sharp) Tipulidae commonly known as crane flies, there is the term "Mugg" (in Stuttgart often "grandfather" called harvestmen are called "Haber Goes."). The change in meaning of the word "Schnake" has meanwhile spread colloquially beyond Swabian. The fly swatter is called in Swabian "Fluigabätschr" or "Muggabatschr" (Mückenbatscher). For something unimaginably small or generally for “a little”, “ Muggle sail ” is used. Literally, "Muggle sail" means the reproductive link of a fly.

- for verbs of movement:

- "Gângâ" or "gâu" (to walk) is only used to describe the change of location - walking as a type of movement means "runâ" in Swabian, running means "springâ" ( hopping means "hopfâ" or "hopsâ"), jumping means “sprengâ” but also “juggâ” ( itch, however, means “bite”); fast running is called "rennâ" or "sauâ" (cf. standard language "whiz"). When the Swabian calls his wife “Alde, sau!”, He does not refer to her as a female pig, but instructs her to run fast. The term "Alde" or "Aldr" is not particularly friendly, but it is quite common among long-term married couples. In addition, young people often use the terms “Alde” or “Aldr” when they talk to one another about their parents; such as B .: "Mei Aldr has des au gsaidt." (My father said that too). If they talk about their parents, that is to say, father and mother, they usually refer to them as "[their] leaders" (people), e.g. B. "Sen your Leit au dâ?" (Are your parents there too?)

- "Gângâ lâu!" Or "Gâu lâu!" (Let go! / Imperative) is not to be understood in the sense of a change of location, but comes from "letting the dough rise", ie "letting it rest". When a Swabian says: "Oh dear, if it's so, ôifach gâu lâu" he means: "What a shit, if that's the case, just leave it alone" And when a Swabian says: "Lame gâu." He means: " Leave me alone."

- On the other hand: "I must now gâu gâu!" Here the first means "gâu" = "same", the second = "go". So: "I have to go right now!"

- For "gâu mr gâu" ("let's go immediately / then") there is the impatience increase "gâu mr gâu gâu" ("let's go now!")

- “Bald” takes on the meaning of the standard German “early” and can also be increased. A Swabian woman can say: "I must morgâ fei aufschdandâ and mai Mâ no bäldr soon!" (I have to get up early tomorrow and my husband even earlier!)

- "G'schwend" (speed) is not used in Swabian to define a speed, but to clarify a time interval: e.g. B. "Komsch du (or 'dâu') mol gschwênd?" = "Are you coming for a moment?"

- to hold means in Swabian "hebâ" (this applies to "hold" both in the sense of "hold on" and in the sense of "be durable, not spoil" and also in the sense of "be stable, do not collapse under stress")

- to lift means "lupfâ" (a nail in the wall "lifts" the picture while the chair is "lifted" on the table).

- Uffhebâ means both keeping a thing and lifting an object from a lower level (floor) to a higher level. The combination of the term in the dialectical abolition could only be formulated in this way by the Swabian Hegel .

- Sitting means "hoggâ" in Swabian and comes from the standard language "squatting" (meaning "crouching down")

- The Swabian calls the standard-language jam "G'sälz", while he underlines "dr (= den) Buddr" (the butter, note that the genus in Swabian is different from standard German ).

- To work means “schaff” in Swabian and create “mach”, while doa / dua (to do) is often used for doing.

- If the Swabian goes to “schaff”, ie to work, he goes “into business”. There he also has “business” in the sense of “Des isch abr a business” (but that's hard work). A shop, however, is called "Lade".

- In some regions there is also dedifferentiation of color attributes: light orange, ocher, and light brown are often combined to form “gäal” (yellow) (see “yellow turnip”), while dark orange, red, pink or purple are called “roâd” or “Rood” (red), analogously, shades of gray are referred to as “black” even with medium brightness levels.

- The personal pronoun “we” is generally “me” in Swabian.

- The question word where? shows the same shift from "w" to "m". In the Swabian main area it is “må?”.

- The indeclinable relative pronoun “wo”, also in Swabian “må”, corresponds to the also indeclinable “so” in Luther German.

- for household items: "Debbich" (carpet) also refers to a (wool) blanket that is suitable for covering.

- nâ (pronunciation closer to 'a') is Swabian for back (from “to”); z. B. Gugg net long, gang nâ! - Don't stare at the air, go there! Furthermore, nâ (pronunciation between 'a' and 'o') stands for “then”, “because”, and in other meanings. It is therefore a particularly common and characteristic word in Swabian. This results in a finely graduated chain from 'a' to 'o': na = down, nâ = towards, nâ = then, nô = still.

- langâ is used as a verb and means “to touch something with your hands”; z. B. Chatter net long, long nâ! - Don't talk long, grab it!

- Another meaning of langâ is "to hit" in the sense of "to smear one": "I lang dr glei Oina"

- But 'hitting' is just as common, e.g. B. "I hit you on the head": "I sleep and Battrie nâ!" (Literally: "I'll hit you on the battery!")

- After all, longâ can also mean "sufficient": "'etzt's enough abb'r!" ("But that's enough!")

- Schmeggâ can also mean “smell” in addition to “taste”.

- There are also reinterpretations regarding the state of mind of individuals. A g'schuggde (form of Meschugge) person is also known as ned whole bacha (half-baked).

- The lunch is in the Swabian 12-17 or 18 am because the terms "morning" and "afternoon" do not exist. So there is only morning ( en dr Fria ), noon, evening and night.

- fai (fine) reinforces a statement or emphasizes an aspect. You could sometimes replace it in the standard language with “really” or “but” or with “by the way”. For example, “Des gôht fai et what Sia dô tastierat!” Would correspond to the standard German sentence “But you can't do what you're trying to do!” In the sentence “Der isch fai z'schnell gfahrá.”, Fai, on the other hand, has an emphatic role: would be with In a car accident, for example, the question of guilt has not been clarified, this sentence would combine the statement “He drove too fast” with the implicit indication that this has an influence on the question of guilt. A further increase results from the combination with “really”: “That isch but fai really z'schnell gfahrá”.

- ha noi is spoken like a word and should correspond most closely to “Ha, no” in standard German. The more common high-linguistic translation of “Oh, no” would only be correct insofar as the half-shocked astonishment implied by “Ha” had to be expressed through emphasis or in the context of the statement.

- If the Swabian denotes the guy , he does not mean a coarse "guy", but rather a "boy" in the meaning of "boy": "Kerle, ..." expresses concern like a standard German "Mensch Junge" or "Junge, ..." ". A "guy" is also not a "Mâ" in a corresponding demarcation: "Bish yes koi guys meh, bisch'a en Mâ." Is demarcation.

- The adjective cheeky is stronger in Swabian, means (still) "outrageous". The at least possible attenuation in standard German to characterize an approximately sympathetic rascal is not present in a comparable way.

Independent vocabulary in Swabian

A large number of Swabian words / vocabulary (mainly used by the older generation) have no equivalent in the standard language. (Hence the dictionaries "Swabian - German"). Of the following numerous examples, however, a larger number are not spread throughout the Swabian language area, but only regionally. The following list can only represent a small selection of the independent Swabian vocabulary.

Nouns ( f = female, m = male, n = neuter, pl = plural)

- Aasl f = armpit

- Afdrmedig m = Tuesday (only regional, especially in the Augsburg area), see below Zaischdig

- Anorak m = jacket

- Bäbb m = glue; but is also used as a paraphrase for "nonsense" ("Schwätz koin Bäbb!")

- Bäbber m = sticker, sticker, adhesive label

- Batsch m = (hand) blow

- Bebbeleskehl / Bebbeleskraut = Brussels sprouts

- Behne f = attic (from stage)

- Bed bottle (a) f = hot water bottle

- Biebli = little boy (boy)

- Blafó m = ceiling (from French le plafond)

- Blätzla n pl = Christmas cookies

- Blôdr f = bladder, especially pig's bladder, swear word

- Bockeschoaß m = roll forward

- Bolle m = ball (e.g. ice cream)

- Bulldog m = tractor (the generic name for tractors derived from the product name Lanz Bulldog is still sometimes used in Swabia, but is increasingly being replaced by Schlebbr = tractor, the word "tractor" is unusual).

- Buckl m = back

- Butzawaggerle = little toddler, flattering or scornful

- Butzameggerler = nasal popula

- Butzastenkl = somersault

- Breedla n pl = biscuit / Christmas biscuits

- Bräschdleng m = strawberry, strawberries

- Brockela / Brogala = peas

- Debbich m = blanket (to cover) (from carpet); even used for tablecloths

- Dreible n, pl Dreibla = currant (from "Träuble" → small grape)

- Droid n = grain

- Droddwar n, from franz. le trottoir = sidewalk

- Dolkâ m, pl = ink stain

- Dõschdig m = Thursday

- Dullâ m, pl = (alcohol) intoxication, cf. ahd. twelan "to numb, to be anesthetized, to show oneself late , to fall asleep" and engl. to dwell

- Stupid d = thumb

- Flädlessubb f = A special type of pancake soup that is widespread in Swabian , Flädle "small flatbread"

- Feet m, pl Fiaß = leg (s), including the feet

- Gaudi = fun, cf. Latin gaudium

- Garbesäeli d = rope to tie together sheaves ( tufts of grain)

- Giggle = small paper or plastic bag, plastic bag, diminutive of "Gugg"

- Gluf f, pl Glufa = pin, safety pin (Glufâmichl = somewhat silly male person)

- Glump / Glomp = junk, scrap, unusable, inferior quality (from "Gelumpe")

- Grädda / Gradda / Kradda m = wicker basket with 1 handle (with 2 handles, see Zonn)

- Grend m = head (see Grind: scab)

- Greiz d = backbone

- Griesi pl = cherries

- Grom = reg gift, souvenir

- Grombir / Äbir f (also nasalized Grombĩr / Äbĩr) = basic pear / earth pear = potato

- Gruuschd m = stuff, stuff

- Gschnuder = cold

- Gschpei = phlegm, sputum

- Gsälz n = jam, accordingly a "Breschdlengsgsälz" is a strawberry jam (see above "Breschdleng")

- Gugg / Guggâ f, pl Gugga / Guggena = bag, according to the Grimm dictionary (Volume IX, Sp. 1030) “look, f., Paper bag, a primarily obd. (Upper German) word "

- Looks n = face

- Gutsle n, pl -la = Christmas cookies (regionally also bonbon / candy)

- Häägamarg n = rose hip butter (as a sweet spread)

- Hafa m, pl Hafa = pot; derived from this: Häfele n = potty; Kochhafa = saucepan; S (ch) dogghafa = (stick pot) flower pot

- Häggr = hiccups

- heidenai! = the screamer!

- Heedscha, Heedsched, Heedschich m = glove

- Hengala = raspberries

- hinneverri = forth

- behind = behind

- Hoggâdse or Hoggâde f = street festival (lit. "squatting")

- Holga = pictures (v. Holy pictures)

- Hoob = chopping knife, cf. Hip

- Joomer m = homesickness, cf. mhd. jamer with a long A

- Kadárr m = cold

- Kánapee n, from franz le canapé = sofa, couch

- Kandl m = gutter

- Kaschde m = cupboard

- Kehrwisch (New Swabian, traditional :) Kaerawisch m = broom, hand brush

- Kerli m pl = boys

- Kischde f = box / alcohol intoxication

- Kittl m = jacket

- Knei d = knee

- Kobbr m = burp

- Kries (e), spoken: Gries (e) = cherries

- Kuddr = garbage

- Kuddrschaufl = shovel for picking up the rubbish

- Loatr d = leader

- Loatrewagge m = cart for the grain harvest

- Loatrewäggeli d = small cart for pulling on foot

- Maurochen = morel

- Mädli pl f = girl

- Meedâle = Eigenart, Macke, Tick (proper "Mödelein")

- Medich, Medig m = Monday

- Meggl m = head

- Migda, Michda m = Wednesday

- Muggeseggele n = smallest Swabian length measure (literally "fly penis")

- Ois (le), Oes f = reddening of the skin, blister

- Pfulba n = pillow

- Poader m = ball

- Poadranuschter m = ball chain (Latin: paternoster; rosary)

- Pfulbe n = pillow

- Pfutzger m = fart, sibilance (when air, gas or steam escapes)

- Quadde, spoken: Gwadde = cockchafer larva

- rode Fläggâ = measles

- Raa n = descent (way back; lit. "down")

- Raane f pl = beetroot

- Ranzâ m = belly (see school satchel, which is carried at the back)

- Saturday m = Saturday / Saturday

- Säeli d = cord (small rope)

- Schässlo (partial stress on the first syllable) = sofa (French chaise longue)

- Schranna f = beer set

- Schmarra m = nonsense, nonsense

- Schniferli n = tiny amount of food

- Suddrae / Suddrä m = cellar (French sous-terrain)

- Sunndig = Sunday

- Schietê (n) = large basket, usually a wooden basket (from "pour" in the meaning of "empty")

- Schlägle n = (non-fatal) stroke, stroke (lit. "Schlägle")

- Schleck m = candy

- Schlettere f = seat board at the rear of a ladder wagon

- Veschpr n = snack (e.g. in the morning during breakfast break, for dinner or when hiking)

- Wegga m, regionally also Weggle n = bread rolls

- Wäffzg f, pl -a = wasp

- Zaischdig / Daeschdich m = Tuesday

- Zibéb f = raisin (from the Arabic zabiba )

- Zonn / Zoana / Zoina f = wicker basket with two handles (with one handle, see Grädda), cf. German- Swiss Zaine = laundry basket and got. tains = basket.

Verbs

- äschdemierâ = respect highly, honor

- åglotza = look at

- abi keie = to fall down

- ousnand keie = disintegrate

- anenend groote = to argue

- bäbbâ = to stick

- batschâ = clap, applaud or hit. I bat you oine also means "I beat you."

- bampa = go to the toilet / poop (expression is mostly used with children)

- seinâ (n) = to stack (from the beige , the pile)

- bledla = to be funny

- blegglâ = to fall

- blodzâ = to fall down, to fall (e.g. as a question to a child: "Bisch nâblodzd?" = "Did you fall?")

- bogglâ = to fall, bump, rumble

- bronzâ = pee / urinate

- bruddlâ = roughly "to scold in a low voice" (cf. Luxembourgish: "braddelen")

- driâlâ = drool, triel, transmit also: dawdle

- drillâ = turn, turn in a circle

- firbâ = to sweep

- flag (â) = lie down, lie there

- flatierâ = flatter, ask, beg

- fuâßlâ = run briskly (slower than "schbrengâ")

- gambâ = to waver, to rock. Especially moving the legs back and forth. Can also be done while sitting. Special case: stepping from one foot to the other (usually with a full bladder). Sometimes also: jump, see folk song

- gigampfa = rocking on the chair

- gosche = to scold

- grageele = to roar around

- gruâbâ = rest, relax

- gugga, part. perf. gugg (e) d = look; nãgugga = (closely) to look; gugg romm! = look here!

- gruuschdle = rummaging around loudly

- hebâ = hold something, do not lift! (cf. lupfâ)

- hoschdubâ = gossip

- hudlâ = to hurry (from "Hud (d) el", a damp cloth used in the bakery to wipe the wood stove to remove the glowing charcoal residues before the loaves of bread were put in; this was not allowed to burn and was therefore moved quickly)

- iberkumme = received

- iberzwärts = over-turned

- hurglâ = balls

- keiâ = to throw

- kobba = burp

- loiba = to waste, to leave (food) behind

- losâ / losnâ / losânâ / lusâ = (to) listen / to listen, cf. engl. to listen !

- luaga, part. perf. gluag (e) d = look (southwest Swabian and generally Alemannic; related to English to look

- lupfâ = (up) to lift (cf. engl. to lift )

- nuâlâ = dig / work

- sauâ = run (in Swabian language, the trainer can call out a "sow!" to a player at any time. This call is not an insult, but only an invitation to exert yourself while sprinting)

- soichâ = to rain, urinate, drip (also used for leaking vessels)

- Schaddra = to laugh

- schbrengâ = run, German "jump" means "hobfâ" in Swabian

- schdräâlâ = to comb (sträâl = comb)

- schdragga = to lie

- schlotzâ = lick (e.g. an ice cream schlotzâ), drink

- schnäddrâ = rattle, sound

- schuggâ = to push

- chat = talk, speak, chat

- dribelierâ = (jmd.) to get on the nerves

- vertlese = sort

- wargla = turn, roll; balls. See also hurgla

...

Adjectives, adverbs and modal particles

- âfangâ = meanwhile

- äbber / äpper / jäapper = someone from still early. sther , cf. something

- äbbes / äppes / jäappes = something

- äggelich = disgusting, disgusting; the word is not related to High German "disgusting", but corresponds to mhd. ege (s) lich, egeslīche = "terrible, terrible, abhorrent", which is based on German * agis "fear", cf. engl. awe

- änâwäâg, oinâwäg = anyway, however

- brifaad = private

- brutal = very / extremely

- därâtwäâgâ (t) = therefore, therefore

- derbies = as soon

- diemol = recently, recently

- fai = but, really

- gau = soon

- gladd = funny, funny, strange (see English "glad" = "happy") - can be increased with the prefix "sau" ("De'sch [j] a saugladd!" = "That's very funny!" ")

- gotzig / gotzich = unique

- gär = steeply (see. Swiss German gärch and high German abruptly ), see. lääg

- bony = pissed off and irascible

- griâbig = leisurely, comfortable

- häälengâ = secretly

- hii / hee / heenich = broken (it's gone )

- it = not

- ko / konn / konni = none / none / none

- lääg = gently rising

- liâdrig = dissolute

- malad = sick

- avoided = tired

- nah (r) sch, narred = angry, angry (to be)

- Näemerd = nobody

- omanand (r) = around, around each other

- pääb / b'häb = very close, very tight (also: crooked; narrow-minded, stingy)

- guess = right

- reng = little, little

- shabbs = crooked

- (uf) z'mol (s) = all at once, suddenly

- sällmål / sälbigsmål = then

- schainds = apparently

- soddige, sogâte, sonige = such

- suschd = otherwise

- probabilities = likely

- weng = a little

- wisawí = opposite (from French: "vis à vis")

- wonderfitzig = curious

- virnemm = to be good / decent

- zwär (ch) = across, cf. High German diaphragm , actually "cross skin," mhd. fur = skin, fur

Prepositions, places, directions

- aa / ah = ab; derived from this: naa / nah / nabe = down , raa / rah = down , abe = down

- ae = a; derived from this: nae = in (not to be confused with Swabian nei = new !) and rae = in

- off = off; derived from this: naus = out , out = out

- gi = to (spatial), e.g. B. gi Schtuegert Laufâ (go to Stuttgart)

- iib (â) r = over; derived from this: nib (o) r = over , rib (o) r = over

- Nääbrânandr = next to each other

- obâ = above; derived from it: doba = up there , hoba = up here

- omm = around; derived from this: nomm = down , (omm…) romm = (around…) around

- ondâ = below; derived from this: donda = down there , honda = down here ("Jetz isch gnug Hae honda" = "Now we've argued enough about it", literally: "Now there's enough hay down here")

- ondâr = under; derived from it: drondor = below , nondor = down , rondor = down

- uff = on; derived from this: nuff = up , ruff = up , uffe = up

- ussâ = outside; derived from this: dussa = outside , hussa = outside here

- hent (â) râ = backwards

- hendârsche = backwards

- fiare, ferre = to the front

- fiarasche = forward

- dur = through

- durâ = through

- äll häck (southwest Swabian), äll ridd / dridd (middle Swabian) = constantly (e.g. "Där guggd äll häck / ridd / dridd over" = "He keeps dropping by (and annoys me!)")

- äll (â) mol / äml / älsâmol = sometimes

- (any) oimâ / ammâ / ommâ / wammâ = (any) where

- Näânâ (ts) (southwest Swabian), närgâds, Näâmârds (central Swabian) = nowhere

- ällaweil / äwe / äwl = always

- allat (Allgäuerisch / Vorarlbergerisch) = always

- ge (directional information ; Swiss German gi / go ) = to / against / gen (e.g. "I gang ge Dibeng" = "I'm going to Tübingen")

- z (location, German once zu ) = in (e.g. "I be z Dibeng" = "I am in Tübingen")

Direction of movement and location in Swabian:

| When something is close to someone or moves away | When something is distant or moving |

|---|---|

| dô = there / here | de (r) t = there |

| dô hanna = here / right here | det danna / dranna = on there / right there |

| gi / uff = to / on | vu / ous = from / from |

| nab / nah = down | rab / rah = down |

| nondr = down | rondr = down |

| honna = down / down here | donna = down there / down there |

| nuff / nauf = up | call / up = up |

| hob / hoba = up here / up here | dob / doba / drob / droba = above / up there |

| herna / hiba = over here / over here | derna / diba / driba = over there / over there |

| nomm / niibr = over | romm / riibr = around / over |

| no = in | rei = in |

| henna = in here / in here | denna / drenna = inside / inside there |

| naus = out | out = out |

| huss / hussa = out / out here | duss / dussa = outside / out there |

For example, if person A is inside a house and person B is outside, then A says: "I bee henna, ond du bisch dussa", while B says in the same situation: "I bee hussa, on du bisch drenna."

French loanwords

Numerous loanwords from French have found their way into Swabian . Examples are:

- äschdimira (enjoy, appreciate, French estimer)

- Blaffo m (ceiling, French le plafond)

- Boddschambor m ( chamber pot, French pot de chambre)

- Buddo m (button, stud earrings, French le bouton)

- Droddwar n (walkway, French le trottoir) (In Stuttgart the name of the street newspaper " Trott-war ", which is mainly sold by the homeless)

- urgent, urgent (urgent, French urgent)

- Sãdamedor m (meter measure, French le centimètre)

- Schässlo m (couch, French chaise longue, literally "long chair")

- Suddrae m (basement, French sous-terrain)

- wiif (on wiifor Kärle = a bright boy, French vif)

- wisewii = opposite

Curiosities

The idioms and sayings listed in this section usually belong to joke and joke literature. That means that they do not belong to the actual everyday language, but are artificially made up and want to amuse or confuse. Alliterations, tongue-twisting word combinations or playing with the numerous Swabian vowel variations that go beyond the vowels of standardized German are preferred as stylistic devices. There are no rules for writing them. A few formulations, on the other hand, do occur in everyday language and are varied according to the situation.

Formulations from everyday language:

- Send d'Henna henna ?, alliterative ("Are the chickens gone?" (Meaning: "in the barn?"))

- Da Abbarad ra dra, alliterating (" carrying the apparatus down")

- En a Gugg nae gugga, alliterating ("looking into a bag")

- Må ganga-mor nå no nã ?, onomatopoeic ("Where are we going then?")

- Mål amål a Mãle nã !, onomatopoeic (" Draw a little man !")

Traditional folk formulations:

- Schället se edd to sällere Schäll, sälle Schäll schälschelt edd. ( Schäll means 'bell', schällâ 'bell' and sallen means 'same'.)

- 's lead a Klötzle lead same with Blaubeura, same lead with Blaubeura lead a Klötzle lead. ("There is a block of lead right next to Blaubeuren, there is a block of lead right next to Blaubeuren"; what is meant is the butcher's rock at Blaubeuren , the tongue twister comes from the fairy tale of the beautiful Lau in Eduard Mörike's Stuttgart Hutzelmännlein )

- In Ulm, around Ulm and around Ulm (a standard German, not a Swabian tongue twister).

- Dr Papscht had bschtellt Schpeckbschtck z spot (Swabian tongue twister).

Formulations from the fun literature:

- Dr Babschd hôt s'Schbätzlesbschtegg zschbäd bschdelld. (The Pope ordered the spaetzle cutlery too late.)

- s'Rad ra draga ond s'Greiz õschlaga ( carry the wheel down and strike the cross: the õ nasally - roughly in the direction of ö and ä - i.e. pronounce Albschwäbisch)

- I han âmôl oen kennd khedd, the hôdd oene kennd. Dui hôdd a Kend khedd, dees hôdd se abbr edd vo sällam khedd. Där hot namely kennd khedd. Se hôdd abbr no an andârâ kennd khedd. Där hôdd no kennd khedd. Ond Wenns se deen nedd khennd khedd hedd, nô hedd se koe Kend khedd. (I once knew someone who knew someone. She had a child, but she did not have that from this one. Because he could no longer [had]. But she also knew someone else. . He could still [had]. And if she hadn't known him, then she would not have had a child.)

- Hitza hodse, saidse, häbse and at night so schwitza miasdse, saidse, dädse. (She has the heat, she says, has it, and she sweats like this at night, she says, it does.)

- Is it all? Who was do do? (Is that all all [empty]? Who was there? [An advertisement for honey])

- oe Åe (middle Swabian) or oa Åa (southwest Swabian ) 'an egg'

- Oa Hoa geid oa Oa. (A chicken lays an egg.)

- Hosch au a oâhgnehm grea âhgschdrichas Gardadierle? (Do you also have an uncomfortably green painted garden door?)

- Do hogged die mo (wo) emmer do hogged (Here sit those who always sit here) Ownership of a regular's table in the pub, usually written continuously to confuse people.

- Schuggschdumi schuggidi (you push me, I push you)

- Moisch d'mõgsch Moschd? Mõgsch Moschd, mõgsch mi. (Do you think you like (apple) cider? Do you like cider, do you like me.)

- Källerätall? ("What time is it?", French source heure est-il?)

Linguistic stratifications

The so-called dignitary Swabian is an "upscale form of language that approximates written German, as it was developed primarily by the Württemberg officials and the Stuttgart bourgeoisie." This way of speaking, which mixes Swabian and standard language elements in different and changing proportions, leads to flowing transitions between pure local dialect , regional dialect forms , regionally colored High German and pure High German. Hermann Fischer judges: "The" notable Swabian "by name in Protestant Old Wuerttemberg brings with it the serious deficiency that not one among hundreds knows and needs the pure local dialect."

Likewise, in the sense of a dialect continuum, there are both differences within the Swabian language area and smooth transitions to the neighboring dialects, in particular to Alemannic and South Franconian.

Newer tendencies

- In the last few decades, as with other German dialects, a strong change towards standard German can be seen. Many classic pronunciation features and vocabulary can only be found in older speakers in rural regions or have already died out.

- Features that have a large radius remain alive (e.g. sch before t or the shortening of the prefix “ge” to g ). Both phenomena are not only Swabian, but also generally Upper German.

- The nasalization generally decreases. From HAD will hand out KED is Kend, from Mo is moon .

- Regional peculiarities are replaced by more spacious Swabian pronunciation features, especially if these are closer to the standard language. For example, the West Swabian oa / åa sounds are gradually being replaced by the more spacious East and Central Swabian oe / åe sounds (for High German / ai / as in “both” or “Meister”).

- There are also developments that cannot be traced back to the influence of standard German. So you can sometimes differentiate between a classic and a newer Swabian form. For example, i hao (“I have”) becomes i han (originally Alemannic / Rhenish Franconian). Likewise neuschwäbisch omitting the swan is â in many positions (z. B. du hedsch take you hedâsch (t) for "you would" or Hendre instead hendâre for "backwards")

- In Bavarian Swabia, in addition to the influence of High German, Swabian is also being pushed back by Bavarian, especially where the Bavarian form is closer to the standard language. So say younger speakers there rather z. B. you have it as your hand .

Swabian spellings

"One of the greatest difficulties in conveying Swabian to others is that there is no suitable script for it."

When it comes to spelling Swabian, the approach taken by the dialect authors can basically be divided into three groups.

- This also applies to many even serious authors who inconsistently handle their writing within the same work. There often seems to be a lack of in-depth reflection on the spelling before writing, as well as a self-critical review after completing a work. This phenomenon is particularly common in the works of commercially oriented Swabian joke literature.

1. The authors only use the written German character set ,

but at the same time try to somehow express what they (from their respective point of view) consider to be Swabian peculiarity with this font. ( Rosemarie Bauer , Kurt Dobler , Manfred Merkel, Bernd Merkle , Doris Oswald , Bernhard Reusch , Lina Stöhr , Winfried Wagner and many others).

- This leads to, so to speak, High German misspellings of various kinds, which are supposed to come more or less close to the actual Swabian pronunciation. Examples: "är hoat", "r hot" u. Ä. m. for written German "he has"; "Mr are", "me / mer / mor send / sänd" u. Ä. m. for written German "we are".

2. The authors use additional self-made diacritical marks .

They are also based on the written German character set, but add their characters to those vowels that do not exist in Standard German. The uncritical use of diacritical marks, however, often gives the impression that the authors concerned have no knowledge of whether and how one of their own special characters is already being used in another European language. So stands z. B. the diacritical mark ˆ in French (from which Swabian once adopted many loanwords !) For a historical s that is no longer written (cf. French maître, German master). The use of this symbol in Swabian is therefore not recommended.

- The self-invented characters lead to spellings like "ar gòht" ( Sebastian Sailer ), "är gòòt / är hòt" (Friedrich E. Vogt), "är gôôt" (polyglot phrasebook Swabian), "blô" , blue ( Michel Buck and Carl and Richard Weitbrecht ) or “blôô” (Hans G. Mayer) or “ho͗t” ( Roland Groner ).

- With regard to the final Schwa sound, they lead to spellings such as “Schreibâ” (numerous authors), “Schreibå” (Roland Groner) and “Schreibα” (Eduard Huber). Usually, however, this unstressed final is written as a simple a (see under group 1), often as a simple e.

- The nasalized a and the nasalized o are often marked with an ellipsis (“i ka '”, “dr Moo'” (moon)) (many authors); very unusual with "àà" at Willi Habermann .

3. The authors use internationally defined diacritical marks from other languages.

The most common case is the use of the tilde (~) over a vowel to mark its nasalization , e.g. B. often with ã or õ, less often with ẽ. (Polyglot phrasebook Swabian; Karl Götz , Roland Groner)

Another diacritical mark is the Danish (not Swedish) ° above the a to characterize its dark pronunciation, e.g. B. “er gåht” for written German “he goes”. (among others with Eduard Huber, Hubert Klausmann)

Additional:

Through the division into three groups, it can be observed that quite a few authors (including Sebastian Blau ) also write the diphthongs “ao” and “au”, which are pronounced differently in Swabian, in a differentiated manner. Such a phonological and written differentiation is less common in the two diphthongs "ei" [eı] and "ai" (mostly Swabian [ae]). Such differentiations are all the more remarkable because they require the authors to recognize that the differentiated pronunciation of these diphthongs in Swabian is often associated with a difference in the meaning of the words (e.g. Swabian Raub (German caterpillar) and Raob (German robbery) )), which is nowhere the case in Standard German. Rudolf Paul made this distinction consistently and impressively in his Bible for Schwoba .

The spelling of a stretch-h , a characteristic of written German (unusual in European comparison), is retained by almost all Swabian dialect authors.

Hubert Klausmann suggests at least in those cases in which Swabian speaks a long vowel and the written German counterpart a short, double spelling of the vowel in question. Such a spelling supports the special Swabian pronunciation of these words.

A broad and colorful, regionally differentiated compilation of classic Swabian poetry and prose can be found in the anthological compilation by Friedrich E. Vogt, Oberdeutsche Mundartdichtung.

Swabian dialect poets and dialect authors

- Ludwig Aurbacher (1784–1847)

- Rosemarie Bauer (* 1936)

- Albin Braig (* 1951)

- Wolfgang Brenneisen (* 1941)

- Michel Buck (1832–1888)

- Sebastian Blau (1901–1986)

- Martin Egg (1915-2007)

- Manfred Eichhorn (* 1951)

- Josef Epple (1789–1846)

- Thomas Felder (* 1953)

- Sieglinde Frank (* 1937)

- Hildegard Gerster-Schwenkel (1923-2016)

- Otto Gittinger (1861–1939)

- Marlies Grötzinger (* 1959)

- Hellmut G. Haasis (* 1942)

- Willi Habermann (1922-2001)

- Hank Häberle (1957-2007)

- Oscar Heiler (1906-1995)

- Manfred Hepperle (1931–2012)

- Eduard Hiller (1818–1902)

- Georg Holzwarth (* 1943)

- Felix Huby (* 1938)

- Peter Pius Irl (* 1944)

- Otto Keller (1875–1931)

- Uli Keuler (* 1952)

- Wilhelm Karl König (* 1935)

- Matthias Koch (1860–1936)

- Hermann Georg Knapp (1828–1890)

- Wool Kriwanek (1949–2003)

- Dominik Kuhn (* 1969)

- August Lämmle (1876–1962)

- Maria Menz (1903-1996)

- Bernd Merkle (* 1943)

- Arthur Maximilian Miller (1901-1992)

- Karl Napf (* 1942)

- Doris Oswald (* 1936)

- Helmut Pfisterer (1931-2010)

- Gerhard Raff (* 1946)

- Willy Reichert (1896–1973)

- Egon Rieble (1925-2016)

- Sebastian Sailer (1714–1777)

- Johann Georg Scheifele (1825–1880)

- Peter Schlack (* 1943)

- Martin Schleker (* 1935)

- Wilhelm Schloz (1894–1972)

- Paul Schmid (1895–1977)

- Walter Schultheiß (* 1924)

- Christoph Sonntag (* 1962)

- Michael Spohn (1942–1985)

- Squidward Troll (1914-1980)

- Wendelin Überzwerch (1893–1962)

- Manfred Wankmüller (1924–1988)

- Paul Wanner (1895–1990)

- Alfred Weitnauer (1905–1974)

- Carl Borromäus Weitzmann (1767–1828)

- Willrecht Wöllhaf (1933–1999)

literature

Dictionaries

(Selection, sorted chronologically)

- Johann Christoph von Schmid: Swabian dictionary, with etymological and historical notes. Stuttgart 1831. ( digitized )

- Dionys Kuen: Upper Swabian dictionary of the peasant language of more than two thousand words and word forms. Buchau 1844 ( digitized facsimile from 1986 )

- Anton Birlinger : Vocabulary for folk from Swabia. Freiburg 1862. ( digitized )

- Hermann Fischer , Wilhelm Pfleiderer: Swabian dictionary . 7 volumes. 1901 (1st delivery; or 1904 1st volume) - 1936 (the dictionary of Swabian that is authoritative to this day).

- Swabian concise dictionary. On the basis of the "Swabian Dictionary" ... edited by Hermann Fischer and Hermann Taigel. 3. Edition. H. Laupp'sche Buchhandlung Mohr Siebeck, Tübingen 1999.

- Susanne Brudermüller: Langenscheidt-Lilliput Swabian . Berlin / Munich 2000.

- Hermann Wax: Etymology of Swabian. History of more than 8,000 Swabian words. 4th, exp. Edition. Tübingen 2011, ISBN 978-3-9809955-1-1 .

Others

- Sebastian Blau : Swabian. (= What is not in the dictionary . Volume VI). Piper Verlag, Munich 1936.

- Karl Bohnenberger : The dialects of Württemberg, a local language teaching. (= Swabian folklore. Book 4). Silberburg-Verlag, Stuttgart 1928.

- Josef Karlmann Brechenmacher : Swabian linguistics in given teaching examples. Attempt of a down-to-earth foundation of creative German lessons . Adolf Bonz & Comp., Stuttgart 1925. (Reprint: Saulgau 1987).

- Ludwig Michael Dorner: Etz isch still go gnuag Hai hunta! Upper Swabian proverbs, idioms, nursery rhymes, songs. Biberach 2017, ISBN 978-3-943391-88-6 .

- Ulrich Engel : Dialect and colloquial language in Württemberg. Contributions to the sociology of language today . Mechanical dissertation University of Tübingen, 1955. ( PDF. )

- Eberhard Frey: Stuttgart Swabian. Phonology and form theory of a Stuttgart idiolect . Elwert, Marburg 1975, ISBN 3-7708-0543-7 .

- Roland Groner: Gschriebå wiå gschwätze. Swabian with all its charms - vivid and realistic; with many concrete examples from everyday life and an extensive collection of words. SP-Verlag, Albstadt 2007, ISBN 978-3-9811017-4-4 .

- August Holder: History of the Swabian dialect poetry . Max Kielmann, Heilbronn 1896. ( commons: File: Holder Schwaebische Dialektdichtung.djvu digitized. )

- Eduard Huber: Swabian for Swabia. A little lesson in language . Silberburg-Verlag, Tübingen 2008, ISBN 978-3-87407-781-1 .

- Friedrich Maurer : On the linguistic history of the German southwest. In: Friedrich Maurer (Ed.): Oberrheiner, Schwaben, Südalemannen. Spaces and forces in the historical structure of the German southwest. (= Work from the Upper Rhine. 2). Hünenburg-Verlag, Strasbourg 1942, pp. 167–336.

- Rudolf Paul: Bible for Schwoba. Schwäbischer Albverein, Stuttgart 2014, ISBN 978-3-920801-59-9 .

- Wolf-Henning Petershagen: Swabian for know-it-alls . Theiss, Stuttgart 2003, ISBN 3-8062-1773-4 . (with follow-up volumes Swabian for those who look through and Swabian for super smart ).

- Wolf-Henning Petershagen: Swabian offensive! An illustrated language teaching in 101 chapters. Silberburg-Verlag, Tübingen 2018, ISBN 978-3-8425-2070-7 .

- Friedrich E. Vogt: Swabian in sound and writing. 2nd Edition. Steinkopf-Verlag, Stuttgart 1979.

swell

- ^ Alfred Lameli: Structures in the language area. Analyzes of the area-typological complexity of dialects in Germany. (= Linguistics - impulses & tendencies. 54). Walter de Gruyter, Berlin / Boston 2013, passim , especially p. 168 ff.

- ^ Fritz Rahn: The Swabian man and his dialect. Stuttgart 1962. (see front and back cover); Friedrich E. Vogt: Swabian in sound and writing. 2nd Edition. Stuttgart 1979. (see front and back cover); Eduard Huber: Swabian for Swabia. Tübingen 2008, p. 127.

- ^ Karl Bohnenberger: The dialects of Württemberg. A dialect language teaching. Silberburg-Verlag, Stuttgart 1929, p. 4f.

- ↑ Eduard Huber: Swabian for Swabians. 2008, p. 17.

- ↑ Friedrich E. Vogt, Schwäbisch in Laut und Schrift, 2nd edition Stuttgart 1979, p. 66, all diphthongs in detail, pp. 67–71.

- ↑ Eduard Huber: Swabian for Swabians. 2009, pp. 21-23; Friedrich Vogt: Swabian in sound and writing. 2nd Edition. 1979, p. 37 ff. And passim.

- ^ Polyglot phrasebook Swabian. 2004, p. 5.

- ↑ B. Rues et al.: Phonetic transcription of German. Tübingen 2007, p. 101.

- ↑ The Swabian position of the "l" and the "r" corresponds to that in the other Germanic languages (Swedish, Danish, Alemannic, etc.). Standard German stands alone here.

- ↑ German dictionary . Volume XIV 2, Column 534, Article We; Damaris Nübling : Klitika in German. Tübingen 1992, p. 253.

- ^ Hermann Fischer: Swabian dictionary. Volume 5, Col. 1.

- ^ Hermann Fischer: Swabian dictionary. Volume 7/1, Col. 914.

- ↑ E.g. Psalm 103 verses 11 + 13 in the original version of Luther (no longer in the editions from 1912)

- ↑ University of Augsburg on the term noon

- ↑ Babette Knöpfle: Schwätz koin Bäpp. Swabian interpreter. Silberburg Verlag, Stuttgart 1999, ISBN 3-87407-101-4 .

- ↑ Hermann Wax: Etymology of Swabian. 3rd edition, p. 559.

- ↑ On the Wasa d Hasa is grazing . In: Volksliederarchiv. free folk song database. Retrieved May 7, 2018.

- ^ Friedrich E. Vogt: Swabian in sound and writing. 2nd Edition. Steinkopf-Verlag, Stuttgart 1979, pp. 149-152.

- ↑ Eduard Mörike: The history of the beautiful Lau. 1858, chap. 3, referred to there as "an old saying ..., of which no scholar in the whole of Swabia knows how to give information about where and how or when it first came to the people".

- ↑ German children's song and children's game. In: Kassel from Kindermund collected in words and ways by Johann Lewalter . Kassel 1911.

- ↑ Huber, Eduard, Schwäbisch für Schwaben, 2008, Silberburg-Verlag Tübingen, ISBN 978-3-87407-781-1 , p. 27

- ^ Mayer, Hans G., More than landscape charms, Mehrstetten 2004, HGM-Verlag, ISBN 3-00-013956-7 , p. 152f.

- ↑ Hermann Fischer, Swabian Dictionary, Tübingen 1904, Volume I, p. XI, note ****

- ↑ Eduard Huber: Swabian for Swabians. 2008, p. 17.

- ↑ Schwäbisch, 2014, p. 8.

- ^ Hubert Klausmann: Swabian. Scientific Book Society, Darmstadt 2014, p. 7.

- ↑ Upper German dialect poetry. Ernst Klett Verlag, 1968, DNB 457721383 , p. 29ff.

Web links

- Werner König: Alemannic-Swabian dialects in Bavaria. In: Historical Lexicon of Bavaria.

- Schwäbisch - Link directory of the University of Portsmouth ( Memento from January 14, 2006 in the Internet Archive )

- Talking linguistic atlas of Baden-Württemberg