Old Synagogue (Heilbronn)

The Heilbronn synagogue was the synagogue of the Jewish community in Heilbronn . The building built by the Stuttgart architect Adolf Wolff from Heilbronn sandstone on the avenue is seen as the high point of the neo-oriental style phase in synagogue construction. It was built from 1873 to 1877, destroyed by arson during the November pogroms on the night of November 9th to 10th, 1938 (“Reichskristallnacht”) and demolished in early 1940. Today a memorial stone and a sculpture commemorate the synagogue.

Location and surroundings

The synagogue was built from 1873 to 1877 on the east side of the southern avenue , which was still sparsely developed at the time , beyond the original city limits of Heilbronn. The property adjacent to the north on Titotstrasse was still undeveloped; on the neighboring property in the south, a doctor had the Villa Gfrörer, named after him, built in the Italian country house style in 1867 . At the time the synagogue was destroyed in 1938, this villa housed the Kahleyss women's clinic. At the same time as the synagogue, which was the dominant building on the southern avenue, the (old) festival hall Harmonie was built on the middle avenue . Between the synagogue and the Harmonie there was only one other building on the east side of the avenue, the rest of the land was still undeveloped. The eastern part of the synagogue site facing Friedensstrasse (today Gymnasiumstrasse) remained undeveloped.

The address of the synagogue was Obere Allee 14 . It was not until 1899 that the four streets Obere Allee , Untere Allee , Obere Alleestraße and Untere Alleestraße became a single street, the avenue, with the houses renumbered . The synagogue was given the address Allee 4 .

The east side of the avenue was gradually built on. On March 15, 1928, more than 50 years after the synagogue was built, the Oberpostdirektion presented plans for a new building for the Heilbronn main post office to replace the old main post office building on the Neckar on the northern neighboring property of the synagogue on the corner of Allee and Titotstrasse (Allee 6) . The new five-story building would have blocked the view of the synagogue. In talks between the post office, the Israelite parish and the city administration, it was possible for the post office to move the new building two meters back, dispense with a porch and keep the roofs flat, so that the synagogue also after the inauguration of the new post office building on February 20, 1931 continued to come into its own.

The new rulers renamed the avenue Adolf-Hitler-Allee in 1933 , so that the address of the synagogue was now Adolf-Hitler-Allee 4 until it was destroyed in 1938 and demolished in 1940 . After the collapse of the Nazi regime, the avenue got its original name again in 1945.

On July 19, 1928, the Heilbronn municipal council decided to take over the private connecting route between Allee and Friedensstrasse, which ran south of the synagogue, to the City of Heilbronn and to widen it. Since it had long been known as Synagogengässchen by the residents, it was called Synagogenweg . In contrast to the Allee, nothing is known about the renaming of the Synagogenweg (which has no house numbers) during the Nazi era. In 1929 it appeared in the Heilbronn address book, and it was also included in the 1934 address book. It was missing in the last address book of the Nazi era in 1938/39. The synagogue path was also missing for a long time in the address books and city maps of the post-war period. Only after 1982 was it entered again on the Heilbronn city map and in the Heilbronn address book.

- View along Heilbronner Allee

Architecture and furnishings

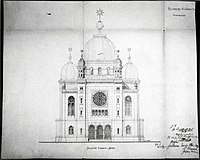

The two-story synagogue, built of Heilbronn sandstone , took up mainly oriental, but also European style elements in its interior and is seen as the high point of the neo-oriental style phase in synagogue construction. It was basically built like a church, but transformed into a synagogue through the use of oriental structures. Like some medieval churches, the synagogue had a double tower facade with a large rose window . The domes were borrowed from Indian or Persian architecture, and Moorish style elements were also used, whereas the tracery of the windows was more reminiscent of Gothic designs.

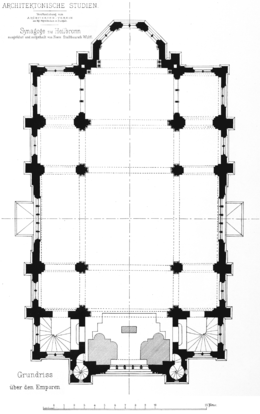

- Floor plans

The synagogue was about 35 m long, 21.5 m wide and including the main dome about 38 m high. It was oriented along a northwest-southeast axis; the front facade facing the avenue was in the northwest. Their ground plan took an intermediate position between a central building and a nave . The building was therefore described both as a central building with side choirs and as a three-aisled long building with central and side aisles or assigned to the type of the nave synagogue with a dome and two-tower facade .

The basic building type was a central building in the form of a Greek cross , which was placed in an approximately square rectangle. The resulting gussets between the cross arms and the rectangle were open as part of the "side aisles". Four large pillars formed a square in the middle of the building and supported a large drum dome . Other pillars separated the "aisles" of the central building, and helped that a three-nave building was built inside the impression, though not a regular column spacing in ships was divided.

This central rectangle was connected to an extension in the east and west over the entire width of the building. In the east this was open to the “main nave” and housed the pulpit. Further to the east, a choir in the form of a protruding, polygonal apse , in which the Torah shrine (Aron-hakodesch) stood. On the sides of the pulpit, in connection with the "side aisles", there was a room for cantor and rabbi . The corresponding extension in the west was designed in the middle as a low entrance hall for the men supported by several columns standing one behind the other, from which three doors led into the interior. On the sides were stairwells that led to the aisle galleries for the women. The central part of the western extension with the front facade facing the avenue protruded. The facade was consequently narrower than the actual structure, the outer west ends of the “side aisles” with domes and Gothic windows were included in the impression that the facade made on the viewer.

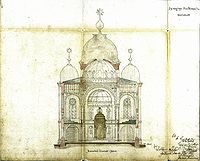

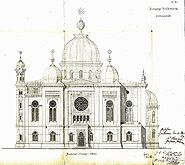

- Views from the building files

The facade was designed in a similar way to the Nuremberg synagogue on Hans-Sachs-Platz, which had also been built according to Wolff's plans : a large rose window with Moorish star ornamentation over a five-part arcade - a frieze dominated the facade. An arch on slender columns framed the rose window and was in turn inserted into an ornamented wall panel. The entrance hall was reached through a three-part portal with arches in the Moorish style. Above the portal was a gilded Hebrew inscription with words from Isaiah 56: 7 ( My house shall be called a house of prayer for all peoples ). Slender turrets with tempietto-like domed attachments closed off both sides of the facade.

The synagogue had flat hip roofs . The roof of the rectangle had a smaller dome at each of its four corners, over the gusset points, without a drum (plinth), which otherwise corresponded to the shape of the large central dome. The tambour of the large central dome had twelve arched windows; the dome itself was covered with patinated, green shimmering copper.

The side view of the synagogue showed the clear floor plan. Two rows of windows were on top of each other, the upper windows being larger than the lower ones. Five fragments of the synagogue windows, which a citizen had recovered and kept after the synagogue fire, were handed over to the Heilbronn city administration in 1988 for the city museums. They were created according to the technique of medieval glass window art , are edged with lead rods, tinted slightly purple and yellow and show vegetable motifs in Art Nouveau style .

In the middle of each of the two long sides, side portals provided access to the inside of the synagogue, which were also provided with rose windows, but were smaller and simpler than the main portal. Pilaster-like wall strips created a vertical division of the building. The sandstone masonry was adorned with rich ornamentation, without any echo of human, animal or other models from nature.

Inside, columns, arches and stucco work took on the forms of the Moorish architectural style of the Alhambra . These decorative forms were subordinate to the European style of the building, which is reminiscent of a medieval church. The pulpit was modeled on church pulpits. Wide ledges in the classicist manner, which separated the lower and upper floors, and Gothic windows also reduced the oriental impression.

The synagogue had three galleries. A gallery in the northwest, above the entrance hall, carried the Walcker organ with 32 stops, two manuals and a console. The galleries above the side aisles, which could be reached via the staircases next to the entrance hall, were intended for women (since there is gender segregation in Jewish places of worship); 33 benches stood here. In the main room, under the central dome, there were 34 benches for the men. In the central dome there was a large brass chandelier with 80 lighting points for gas and electric light. The inside of the dome was supported on strong pilasters, which were adorned with bundled half-columns at the level of the galleries and in the form of services in front of the pillar.

The south-eastern end of the building was formed by a vaulted, polygonal (five-part) choir , which had a Gothic appearance , behind a high horseshoe arch . Three large choir windows showed the Star of David (Hebrew: מגן דוד, Magen David, German: “Shield of David”) in multiple variations in their upper parts as decorative tracery .

In this choir stood the Torah shrine imposed with a parochet (Hebrew: ארון הקודש, Aron ha-Qodesch, German: "Holy Ark"). It combined the Moorish forms of the interior with the shape of the domes and was decorated with rich stucco work. The Almemor (English: prayer desk) was set up a little higher in front of the Torah shrine. A light, called Ner Tamid, or Eternal Light, hung over the shrine . The oak pulpit was installed diagonally to the right of the Torah shrine.

history

Planning, construction and inauguration

From 1830, Jews settled in Heilbronn for the first time in 354 years. The Jewish community in Heilbronn grew rapidly from the middle of the 19th century onwards, due to further influx, especially from rural communities. On October 21, 1861, she broke away from her mother parish in Sontheim and formed an independent Israelite church community. The Lehrensteinsfeld district rabbinate , which is superordinate to the Israelite parishes , was relocated to Heilbronn on July 1, 1867. In 1862 there were 137 Jews in Heilbronn, in the census of 1864 there were 369, in 1871 it was 610.

The only synagogue in the city at that time had been in the central building of the Deutschhof since 1857 , but the space there was limited. The parish church council decided on February 1, 1865 to purchase a plot of land on the avenue for 10,000 guilders. Since the decision was not made unanimously, the purchase could not take place until 1871 after fierce controversy, with the price of the land already rising to 16,000 guilders. The building decision was made on June 21, 1871. In 1873, the design by Stuttgart architect Adolf Wolff was approved, who built the third synagogue in Heilbronn after the Stuttgart (1859 to 1861) and Ulm (1870 to 1873) synagogues. With 60 to four votes, the community assembly decided to set up a synagogue organ , although instrumental music is not provided for in the Orthodox liturgy and therefore there was a conflict with the Orthodox community members. The cost of the new synagogue amounted to a total of 372,778 marks, of which the municipality of Heilbronn made 30,000 guilders (51,428 Reichsmarks) available in 1876 through a loan from the foundation maintenance funds.

The foundation stone was laid in mid-August 1873, the topping-out ceremony was held on November 23, 1874, and construction was completed by the end of May 1877. On June 7th, 1877, the Torah scrolls were brought from the prayer room in the Deutschhof to an adjoining room of the new synagogue, and on June 8th the synagogue was inaugurated. After a farewell service in the prayer room in the Deutschhof (the "old synagogue"), the seven Torah scrolls entered the new synagogue at 11 o'clock, followed by a sermon and dedication prayer by Rabbi Moses Engelbert . The festive day ended with a lunchtime gala dinner in the Rose restaurant with many representatives from official bodies and an evening gala ball in the Harmonie festival hall .

Destroyed by arson in 1938

From then on, the religious life of Heilbronn's Jewish community took place in the synagogue. In May 1927, the 50th anniversary of the synagogue was celebrated with a ceremony and a commemorative publication on the history of the Jews in Heilbronn.

Eleven years later came the end of the Heilbronn synagogue. Like many other synagogues in the German Reich, it was destroyed by arson on the night of November 9th to 10th, 1938, the so-called " Reichskristallnacht " or Reichspogromnacht .

On November 9, 1938, the NSDAP leadership gathered in Munich to celebrate the 15th anniversary of the “ March on the Feldherrnhalle ” . The order issued from there to anti-Jewish riots after the assassination attempt on a German embassy employee in Paris seems to have reached the Heilbronn NSDAP by telephone at 11:30 p.m., probably through several intermediate stages. According to court findings from 1950/51, the Heilbronn NSDAP district leader, Richard Drauz , was thinking of imposing a heavy fine on the Heilbronn Jews instead of staging “popular anger” that harmed the “reputation of the NSDAP at home and abroad” . In the letter from a lawyer, which is in the case files, there is talk of "confiscation or levying of a contribution of 100,000 marks". The fact that the district leader did not get through with this project "upwards" was the reason that Heilbronn came "behind". It is unclear whether Drauz was present in Heilbronn that night or negotiated with higher NSDAP authorities from abroad.

The Heilbronn synagogue did not burn until the morning of November 10th, a few hours after the other arson attacks, and the other riots of the November pogroms in Heilbronn only took place on the evening of November 10th, unlike elsewhere mostly on the night of September 9th to 10th November. Drauz's negotiations had probably taken some time, so that that night there was only time for a single action - the synagogue arson - and the other acts of devastation among Jewish private and business people only took place under cover of darkness the next night.

There are various, sometimes contradicting statements about the course of the fire, some of which were only given orally after decades, so they should be treated with caution. Passers-by and a gynecologist living in the immediate vicinity of the synagogue claim to have heard noises “like the clatter of petrol cans” in the synagogue at around one o'clock in the morning on November 10, 1938; The latter claims to have alerted the fire brigade at this point in concern for his clinic (which is located next to the synagogue). Other information about when the fire department was alerted vary between three and five in the morning. It seems likely that the perpetrators were already gathering combustible material in the synagogue at one o'clock in the morning and pouring gasoline over it.

Around five o'clock, residents heard two violent detonations. This corresponds to the information in a newspaper article published on November 11, 1938 in the Nazi-dominated Heilbronner Tagblatt , according to which the synagogue burned at five o'clock. In a poem with which a firefighter from Heilbronn who was involved in the extinguishing work made fun of the synagogue fire, the time for the fire to become known is mentioned as “The morning at the 6th hour”. Local residents said they heard vivid noises around 6 or 6:30 a.m. about the synagogue fire. Shortly after seven o'clock, according to the Heilbronner Tagblatt, the dome of the synagogue also burned outside, which is confirmed by a photo that, according to the photographer, was taken shortly before seven in the morning. Another photograph shows the synagogue with a burned out dome and numerous onlookers and can be dated to 8:42 a.m. thanks to the clock at the post office shown in the picture.

The role of the Heilbronn fire brigade in the synagogue fire has not been conclusively clarified. What is clear is that she did not put out the fire in the synagogue, but limited herself to protecting the surrounding buildings; this is reported by both the newspaper article in the Heilbronner Tagblatt and the fire poem by the Heilbronner fireman. The newspaper article writes that “the fire fighters could break into the synagogue, which was filled with smoke and smoke”, “even with gas masks on” proved impossible. The firefighters also emphasized in later legal proceedings that an intrusion was no longer possible. On the other hand, it can be inferred from the fire fighter's poem that extinguishing the fire - regardless of whether this was still possible or not - was not even intended, but on the contrary the fire brigade ensured the necessary passage by forcibly opening the door Fire spread:

|

The fire brigade, you have to let that |

We had to pick the door first, |

The allegation made in fire brigade circles after the Second World War that the mayor present at the scene of the fire ( Heinrich Valid ) placed the fire brigade under his orders and forbade the fire brigade to be extinguished, is regarded as unlikely and is just as unprovable as the suspicion made anonymously to Hans Franke in 1961, the Fire brigade "extinguished" with petrol. The 200-liter barrel of gasoline, which one of the photographers of the burning synagogue claims to have seen under the synagogue's dome according to a newspaper article from 1958, can neither be proven nor recognized in one of his photographs. The commander of the Heilbronn fire brigade was brought to court in 1939 in matters of synagogue arson, but acquitted on October 2, 1939 for lack of evidence.

Demolition of the ruin and further fate

On November 30, 1938, the municipality of Heilbronn bought the synagogue property from the Israelitische Kultusgemeinde. For the removal of the rubble, she demanded 10,000 Reichsmarks from the community, which was offset against the purchase price of 10,000 Reichsmarks. The completely burned-out ruins of the synagogue remained standing until mid-January 1940, when the Koch & Mayer company began demolishing on behalf of the city administration. At a closed municipal council meeting on February 23, 1940, the fate of the synagogue ruins was discussed. Lord Mayor Valid reported that the company commissioned with the demolition and removal of the ruin had estimated 34,000 Reichsmarks for this and set 10,000 Reichsmarks as the value of the demolition material remaining in the hands of the city. The whereabouts of the stones of the synagogue is unclear, according to various reports they were used to build streets or walls in Heilbronn.

After the end of the Nazi regime, the synagogue property came to be owned by the cinema operator Ludwig Stern, a Jewish Heilbronn native who had a cinema built on it in 1948/49. “Out of consideration for the former site of the synagogue”, Stern deliberately built the Scala light show, which opened on November 27, 1949, on the rear part of the property on Gymnasiumstrasse. The Hillebrecht concert café was also located in the cinema building .

Two years later, on November 22, 1951, the Gaildorf manufacturer Wilhelm Bott took over the Scala-Lichtspiele (renamed Metropol-Lichtspieltheater on May 1, 1952 ) and the synagogue property at a foreclosure auction . On June 21, 1952, Hillebrecht opened a fast-food restaurant and a restaurant-concert garden with dancing on the front part of the synagogue grounds on the avenue. In 1956, this part of the property was built over with another cinema, the Universum , which opened on September 13th . In 1989/1990 the Bott-Filmtheaterbetriebe sold the property to the neighboring publishing house of Heilbronner Demokratie , which leased the cinemas. After the cinemas located there closed in July 2000, the Metropol building erected in 1948/49 on the rear part of the property, for which no new tenant could be found, was demolished at the beginning of 2001; this part of the property has been used as a parking lot since then.

In 2003 Avital Toren, as the head of the new Jewish community in Heilbronn, was interested in renting rooms in the cinema center on the site of the former synagogue. This failed because of the high renovation costs that would have been caused by security regulations for Jewish institutions in Germany, so that other rooms were rented.

Legal processing of the arson

Who set the Heilbronn synagogue on fire and who gave the order on site could not be officially clarified. As early as 1939 the commander of the Heilbronn fire brigade was indicted in the matter of synagogue arson, but acquitted on October 2, 1939 for lack of evidence.

After the Second World War, the Heilbronn public prosecutor dealt with the synagogue fire in three proceedings from 1946/50, 1953 and 1955. All three negotiations were discontinued due to a lack of evidence and the files have since been destroyed. A total of seven people were charged in these three trials. Several court proceedings also dealt with the synagogue fire, without any useful information being generated for the process. Even decades later, “all investigations met with persistent silence” or “at most led to cryptic hints”, so that the name of the actual arsonist could not be determined. A single perpetrator can be excluded because of the extensive preparations. It can be assumed that the perpetrators belonged to the NSDAP and are possibly to be found among the seven defendants of the post-war period. In the Heilbronn case, there is no evidence of the involvement of foreign SA men, which can be proven elsewhere, but it cannot be ruled out either.

The whereabouts of the cult objects

There is no reliable information about the whereabouts of the cult objects ( Torah scrolls , phylacteries, etc.). Statements made by witnesses in this regard contradict one another and range from early removal to partial rescue and complete destruction. It is said to have been observed how the cult objects were carried "early" into the Oberamt (meaning the Oberamt building diagonally opposite). According to another witness on the evening of November 10, Jewish ritual objects were in the Turner Room of the old Heilbronner Festhalle "at certain intervals" harmony brought, including Torah scrolls, tefillin, banners in Hebrew and Jewish books of account.

According to Hans Franke (1963), the Torah scrolls and other cult objects, some of which were set with precious stones, were valued at 8,000 DM. One of the Heilbronn Torah scrolls is said to have been saved and is now in a synagogue in Baltimore .

The Heilbronn Police Director W. announced in a letter dated May 9, 1962 that he believed he remembered that the cult objects were kept in the files (top floor) of the Heilbronn Gestapo (House Wilhelmstrasse 4) or at least that they were stored there for some time. For Schrenk, nothing certain is known about the whereabouts of the cult objects; Since almost no remains have emerged so far, one must assume that the destruction of the synagogue was also aimed at the destruction of the cult objects.

Attempts were made to obtain more detailed information about the whereabouts of the cult objects from the reparation applications submitted by the Heilbronn Jewish institutions in accordance with the Federal Compensation Act after the Second World War . Although there are references to sources that such applications were made, they can no longer be found in the files of the responsible authorities. The reimbursement statistics only contain references to registrations of securities and bank balances, but not of furnishings or cult objects.

Memorials and remembrance

In 1960, Mayor Paul Meyle suggested that a memorial should be created on the occasion of the 25th anniversary of the synagogue fire in 1963. First considerations of the city administration envisaged a plate on the north wall of the Universum cinema, which should represent the burning synagogue. Later they thought of a three-meter-high granite obelisk with a Star of David, which was to be erected at the post office on the southern side of the pedestrian crossing across the avenue.

Even two years later, no memorial stone was erected. Various alternatives were considered, which could be seen in the spring of 1965 in the form of dummies on the median of the southern avenue in front of the Universum Cinema, but none of them met with approval.

On November 9, 1966, a memorial stone with a bronze inscription plate was unveiled on the median of the avenue. The 1.45 meter high, 90 centimeter wide and 30 centimeter deep memorial stone was carved by the sculptor Rückert; it consists of Heilbronn sandstone, the building material of the synagogue. The letters for the inscription on the 60 by 60 centimeter bronze plate were designed according to a design by the Heilbronn graphic artist and city councilor Gerhard Binder . The inscription refers to the synagogue once located here and the arson in 1938.

When the construction of the pedestrian underpass on the southern avenue began in 1978, the memorial stone was temporarily removed. After the construction work was completed in 1980, it was moved to the confluence of the Synagogenweg, i.e. in the immediate vicinity of the former synagogue site, and it was worked into the concrete parapet to the post office underpass.

In 1982 the local newspaper reported on the letter to the editor from the Heilbronn Jew, James May (Julius Mai), who had emigrated to the USA, demanding the "demolition of the current porn cinema and the stupid Jewish monument at the entrance to these pleasure palaces" and the planting of an arboretum at the former synagogue site. The owners of the cinemas protested against May's choice of words “porn cinemas” and against the demolition he proposed. The city administration pointed out that they could not tear down other people's houses.

To mark the 50th anniversary of the November pogroms, a special stamp was issued in Israel on November 9, 1988 , showing a picture of the Heilbronn synagogue in a burning book. The associated first day card shows a photograph of the former Heilbronn synagogue.

In addition to the memorial plaque from 1966, the dome memorial by the artist Bettina Bürkle, inaugurated on May 5, 1993, is intended to commemorate the destroyed synagogue in Heilbronn. The memorial consists of a metal framework in the shape of the overturned dome of the Heilbronn synagogue and is also located near the former synagogue location in front of the cinema building on the avenue.

After the Postpassage was closed, a new memorial was created from the memorial stone and dome in October / November 2009 . The memorial stone is now in an anthracite-colored concrete block. In front of the concrete block, an opening was made in the ground - surrounded by cobblestones - for the Hanukkah , which is otherwise covered with a golden lock. Bürkle's dome sculpture was placed next to the block at the confluence with Synagogenweg. The ensemble was created in collaboration between the building department, museum and the Heilbronn Jewish community.

A private person created a virtual reconstruction of the exterior view of the building based on the synagogue blueprints, which has been shown on the Internet since 2010.

See also

literature

- Hans Franke : History and Fate of the Jews in Heilbronn. From the Middle Ages to the time of the National Socialist persecution (1050–1945). Heilbronn City Archives, Heilbronn 1963, ISBN 3-928990-04-7 ( PDF, 1.2 MB ).

-

Joachim Hahn and Jürgen Krüger : Synagogues in Baden-Württemberg . Volume 1: Jürgen Krüger: History and Architecture , Volume 2: Joachim Hahn: Places and facilities . Theiss, Stuttgart 2007, ISBN 978-3-8062-1843-5 (memorial book of the synagogues in Germany, 4).

On the Heilbronn Synagogue, pp. 151 to 152 in the first and pp. 190 to 195 in the second volume . - Harold Hammer-Schenk : Synagogues in Germany. History of a building type in the 19th and 20th centuries 20th century , Hans Christians Verlag, Hamburg 1981, part 1, p. 321 and part 2, fig. 233.

-

Hannelore Künzl : Islamic style elements in synagogue construction of the 19th and early 20th centuries. Publishing house Peter Lang, Frankfurt am Main u. a. 1984, ISBN 3-8204-8034-X (Judaism and Environment, 9).

To the Heilbronn Synagogue pp. 334 to 337 . - Christhard Schrenk : The chronology of the so-called "Reichskristallnacht" in Heilbronn. In: Yearbook for Swabian-Franconian History 32nd Historischer Verein Heilbronn, Heilbronn 1992. pp. 293–314.

References and comments

- ↑ a b Hahn / Krüger, part volume 1, p. 152

-

↑ Unless otherwise indicated, the section on location and surroundings follows the work of

Roland Reitmann: Die Allee in Heilbronn. Functional change in a street . Heilbronn City Archives, Heilbronn 1971 (Small series of publications by the Heilbronn City Archives, 2); There especially p. 21 to 23 as well as the enclosed maps of the avenue in the years 1879, 1911 and 1939. - ↑ Reitmann, p. 28, and Franke (see literature), p. 125

- ^ The street was first called Schafhausweg , from 1867 Schafhausstraße , from 1871 Friedensstraße . In 1948 it was renamed Gymnasiumstrasse . Source: Gerhard Schwinghammer and Reiner Makowski: The Heilbronner street names . 1st edition. Silberburg-Verlag, Tübingen 2005, ISBN 978-3-87407-677-7 . P. 88

- ↑ Oskar Mayer states in The History of the Jews in Heilbronn , Heilbronn am Neckar 1927, on p. 65 the “acquisition of a building site between avenue and Friedensstraße”. The official city maps of Heilbronn from 1925 and 1938 show the rear part of the property as undeveloped. This part was not built until 1949 (see section Demolition of the Ruin and Further Fate ).

- ^ Friedrich Dürr , Karl Wulle, Willy Dürr, Helmut Schmolz, Werner Föll: Chronicle of the City of Heilbronn. Volume III: 1922-1933 . Heilbronn City Archives, Heilbronn 1986 (Publications of the Heilbronn City Archives, 29). P. 333

- ↑ Dürr u. a .: Chronicle of the city of Heilbronn III . P. 518

- ↑ On the new post office s. Krüger / Hahn (see literature), part volume 2, p. 192, as well as the text on the Heilbronn synagogue at alemannia-judaica.de (see web links).

- ↑ a b Makowski / Schwinghammer: The Heilbronn street names . P. 23

- ^ Dürr et al.: Chronicle of the City of Heilbronn III . P. 352

- ^ Makowski / Schwinghammer: The Heilbronner street names . P. 196

- ↑ On the Synagogenweg in the Heilbronn address books: Hans Georg Frank: Synagogenweg in Heilbronn - Never forget even without a sign . In: Heilbronner Voice of December 8, 1982 (No. 282), p. 10

- ↑ The building description essentially follows: Hannelore Künzl: Islamic stylistic elements in synagogue construction in the 19th and early 20th centuries (see literature), pp. 334 to 337. Franke (see literature), pp. 73 to 75, was also used .

- ↑ a b Künzl, Islamische ... , p. 370

- ↑ a b c d e Künzl, Islamische… , p. 336

- ↑ Dimensions (including the external stairs) according to the floor plans and the view in Architectural Studies . Stuttgart, Wittwer. H. 57, sheet 2, and H. 60, sheet 1 (around 1877)

- ↑ Künzl, Islamische ... , p. 283

- ↑ Franke, p. 73

- ↑ a b c d e f g h Hahn / Krüger, Part 2, p. 192

- ^ Hannelore Künzl: Jewish Art. From biblical times to the present. Beck, Munich 1992, ISBN 3-406-36799-2 . P. 146

- ↑ Künzl, Islamische ... , p. 335

- ↑ Künzl, Islamische ... , p. 332

- ↑ Hebrew: ביתי בית תפלה יקרא לכל העמים

- ↑ a b c d e f g Franke, p. 74

- ↑ Ludwig Klasen (Ed.): Ground plan models of buildings for church purposes . Baumgärtner, Leipzig 1889 (ground plan models of all kinds of buildings, XI). P. 1481

- ↑ a b c d e Uwe Jacobi: On the trail of the Reichskristallnacht . In: Heilbronner Voice of November 30, 1988, p. 19

- ↑ a b c d e Franke, p. 75

- ↑ Künzl, Islamische… , p. 336f.

- ↑ a b Helmut Schmolz, Hubert Weckbach: Heilbronn with Böckingen, Neckargartach, Sontheim. The old city in words and pictures . 3. Edition. Konrad, Weißenhorn 1966 (publications of the archive of the city of Heilbronn, 14). No. 59: Synagogue on the Allee, 1894 . P. 47

- ↑ a b Franke, p. 74f.

- ↑ Christhard Schrenk , Hubert Weckbach , Susanne Schlösser: From Helibrunna to Heilbronn. A city history (= publications of the archive of the city of Heilbronn . Volume 36 ). Theiss, Stuttgart 1998, ISBN 3-8062-1333-X , p. 158 .

- ^ The presentation of the section follows Franke, pp. 53 to 73.

- ^ Hahn / Krüger, Teilband 2, S. 193. Title of the festschrift: Oskar Mayer: The history of the Jews in Heilbronn. Festschrift for the 50th anniversary of the synagogue in Heilbronn . Heilbronn am Neckar, 1927 (Reprint: Heilbronn, 1987)

- ↑ The chronology follows the essay, written in 1988 and published in 1992, The Chronology of the so-called “Reichskristallnacht” in Heilbronn (see literature) by Christhard Schrenk, the director of the Heilbronn City Archives.

- ^ Franke, History and Fate of the Jews in Heilbronn (see literature), p. 125, and Schrenk, p. 296 and 310

- ↑ Lt. Schrenk, p. 308 and notes 38 and 60 on p. 313, the trial files are in the Ludwigsburg State Archives , holdings EL 312 (Heilbronn Public Prosecutor's Office), Bü 40 (KMs 5/50).

- ↑ Drauz according to the court documents from 1950/51, in Schrenk on p. 308

- ↑ Schrenk, pp. 307-310, in contrast to Franke, who (p. 125) assumes that Drauz was not in Heilbronn.

- ↑ Schrenk, p. 310

- ↑ Franke, p. 125f.

- ↑ Franke, p. 126, and Schrenk, p. 300

- ↑ Lt. Schrenk, p. 297, this happened frequently.

- ↑ Schrenk, p. 296 ff., And Franke, there on p. 130 ff. Completely printed (also in the PDF file available online on p. 128 ff. And here )

- ↑ The poem is entitled Der Brand . According to his own later statements at various court hearings after 1945, the author often recited joking poems at comradeship evenings for the fire brigade. The poem, which he is sorry to have written, sprang from his “poetic and humorous streak”. Lt. Schrenk, p. 297 and note 24 on p. 312, it can be found in the main state archive in Stuttgart in holdings J 355, Bü V 242; publication was approved on July 13, 1989.

- ↑ Franke, p. 126

- ↑ This picture on alemannia-judaica.de; also as Figure 115 for the Schrenks article and in Franke on p. 127

- ↑ a b c d e Schrenk, p. 300

- ^ Probably this picture on alemannia-judaica.de

- ↑ Schrenk, pp. 297-300

- ↑ Schrenk, p. 300; According to notes 25 and 30 on pages 312 and 313, it is a newspaper article by Lothar F. Strobl in Neckar-Echo of November 11, 1958, p. 7.

- ↑ Uwe Jacobi: That was the 20th century in Heilbronn . Wartberg Verlag, Gudensberg-Gleichen 2001, ISBN 3-86134-703-2 . P. 42: 1938: November 30th: The city takes over the synagogue site

- ↑ Schrenk, p. 311

- ↑ Susanne Schlösser: Chronicle of the city of Heilbronn. Volume IV: 1933-1938 . Heilbronn City Archives, Heilbronn 2001, ISBN 3-928990-77-2 (Publications of the Heilbronn City Archives, 39). P. 441

- ↑ Lt. Schrenk, p. 301 and note 35 on p. 313, according to a report in the Heilbronner Tagblatt from January 19, 1940 (p. 5). Lt. Note 36 on p. 313 is wrong when Franke dates the beginning of the demolition of the synagogue on 16 February 1940 on p. 128.

- ^ Franke, p. 135f., And Uwe Jacobi: The missed council minutes . 3. Edition. Verlag Heilbronner Demokratie, Heilbronn 1995, ISBN 3-921923-09-3 , p. 82f.

- ↑ Alexander Renz: Chronicle of the city of Heilbronn. Volume VI: 1945-1951 . Heilbronn City Archives, Heilbronn 1995, ISBN 3-928990-55-1 (Publications of the Heilbronn City Archives, 34). Pp. 273 and 333

- ↑ Alexander Renz: Chronicle of the city of Heilbronn. Volume VII: 1952-1957 . Heilbronn City Archives, Heilbronn 1996, ISBN 3-928990-60-8 (Publications of the Heilbronn City Archives, 35). P. 26

- ↑ Alexander Renz: Chronicle of the city of Heilbronn. Volume VI: 1945-1951 . Heilbronn City Archives, Heilbronn 1995, ISBN 3-928990-55-1 (Publications of the Heilbronn City Archives, 34). P. 548

- ↑ Alexander Renz: Chronicle of the city of Heilbronn. Volume VII: 1952-1957 . Heilbronn City Archives, Heilbronn 1996, ISBN 3-928990-60-8 (Publications of the Heilbronn City Archives, 35). P. 36

- ↑ Alexander Renz: Chronicle of the city of Heilbronn. Volume VII: 1952-1957 . Heilbronn City Archives, Heilbronn 1996, ISBN 3-928990-60-8 (Publications of the Heilbronn City Archives, 35). P. 373

- ↑ Historisches Heilbronn 1974: Meeting point cinema . In: Heilbronner Voice from June 20, 2001

- ↑ The excavator is already gnawing at the Metropol cinema . In: Heilbronner Voice of February 28, 2001

-

^ Maria Theresia Heitlinger: New Synagogue on Synagogenweg? In: Heilbronner Voice from August 19, 2003

Maria Theresia Heitlinger: Association for a synagogue founded in Heilbronn . In: Heilbronner Voice of March 19, 2004

Maria Theresia Heitlinger: Jewish life blossoms anew on Allee . In: Heilbronner Voice of December 2, 2004 - ↑ a b The presentation of the legal processing follows Schrenk, p. 300 ff.

- ↑ All of the following testimony according to Franke, Die Geschichte der Juden in Heilbronn (see literature), p. 128

- ↑ a b c Schrenk, p. 301

- ↑ a b Franke, p. 128

- ↑ Hahn / Krüger, Teilband 2, p. 193 and almost identical to the text of the Alemannia Judaica website (accessed on January 12, 2008)

- ↑ (as of 1988 and 1992)

- ↑ Lt. Schrenk, p. 301 and note 33 on p. 313, in the main state archive in Stuttgart, inventory J 3555, Bü V 252

- ↑ Lt. Schrenk, p. 301 and note 34 on p. 313, the State Office for Reparation Baden-Wuerttemberg, the Arbitrator for Reparation at the Stuttgart District Court, the Oberfinanzdirektion Stuttgart and the Federal Central Office for applications according to the Federal Compensation Act at the State Pension Authority of Düsseldorf were asked to.

- ^ Gk: 100 years Heilbronn Synagogue . In: Heilbronner Voice of December 31, 1977 (No. 302), p. 14

- ^ WDA: Memorial stone for the synagogue . In: Neckar-Echo from May 2, 1963 (No. 101)

-

^ Jac: Looking for a new solution for the synagogue memorial . In: Heilbronner Voice of March 30, 1965 (No. 74), p. 9

WDA: “We don't want to have a tomb” . In: Neckar-Echo of March 30, 1965

WDA: New ideas make further discussions necessary . In: Neckar-Echo of April 13, 1965 (No. 86)

jac: Different solutions for synagogue memorial . In: Heilbronner Voice of April 13, 1965, p. 10 - ^ A b c Hans Georg Frank: Demolition of the Heilbronn cinema "Lustpalast": An unreal demand . In: Heilbronner Voice of August 21, 1982, p. 19

- ^ Helmut Schmolz and Hubert Weckbach: Heilbronn. History and life of a city . 2nd Edition. Konrad, Weißenhorn 1973, ISBN 3-87437-062-3 . No. 520: Memorial stone to the fire in the synagogue, 1966 . P. 154

- ^ Official Journal for the city and district of Heilbronn . 22nd year, Heilbronn 1966, No. 45 of November 18, 1966. p. 1

- ↑ Memorial stone: New place? . In: Heilbronner Voice of November 14, 1978 (No. 263), p. 13

- ↑ wda: Synagogue memorial stone now in a cheaper place . In: Heilbronn Voice of June 4, 1980 (No. 128)

- ↑ Image of the stamp here on the website of alemannia-judaica.de.

- ↑ Uwe Jacobi: That was the 20th century in Heilbronn . Wartberg-Verlag, Gudensberg-Gleichen 2001, ISBN 3-86134-703-2 . P. 97

- ^ Kra: Memorial redesigned . In: Heilbronn voice . November 7th, 2009 ( from Stimme.de [accessed November 7th, 2009]).

- ↑ Kilian Krauth: Dean: Monuments alone are not enough . In: Heilbronn voice . November 10, 2009 ( from Stimme.de [accessed November 10, 2009]).

- ^ Gertrud Schubert: Stroll around the Heilbronn synagogue . In: Heilbronn voice . November 8, 2010 ( from Stimme.de [accessed July 26, 2013]).

Web links

Coordinates: 49 ° 8 ′ 24 ″ N , 9 ° 13 ′ 18.5 ″ E