Double tower facade

Double tower facade , also known as two-tower facade , describes a defining design motif of large church buildings whose main portal, which is usually located on the narrow western side, is flanked by the corner towers towering over the gable . The double tower facade was created in the Romanesque architecture of Western Europe from the 11th century onwards from the type of western building on basilicas . In the Gothic period , the double tower facade was a characteristic feature of French cathedrals in particular . Their forerunners may be found in early Christian Syrian church building. According to the architectural connection to the nave , westworks with twin towers are differentiated as independent structures from double tower facades , the towers of which form a "harmonious" unit with the nave (French façade harmonique ). The west front of the monastery church of St-Étienne de Caen is considered to be the oldest of these stylistically defined double tower facades .

Form and function

Towards the beginning of the 5th century, the design of the late Roman Christian basilica acquired religious and symbolic significance. The entire building was interpreted as a model of an ancient city, the structural elements of which should be found in the individual components of the church building. The portal in the west facade corresponds to the gate of the walled Roman city , the nave corresponds to the cardo in the center of the city, lined with arcade halls, and the transept corresponds to the decumanus running at right angles to the cardo . The triumphal arch in front of the apse becomes a miniature of the late antique triumphal arch spanning the boulevard and the chancel is designed like the emperor's throne room. The pillars of the nave embody the apostles , who carry the state of God with the roof of the building. In early Christian times, the church as a symbol of the city did not have the protective function of a walled city, as it was usually in the center of it. Just like the gate flanked by two towers symbolically transforms the church into a city, this motif appears on Roman coins, where it stands for the Roman Empire in general and for Rome in particular . In the Revelation of John , a heavenly Jerusalem appears at the end of all days . This vision is presented and visually implemented according to the plan of a real Roman city. The circular ideal image of the heavenly city finds its microcosmic counterpart in the wheel chandelier that hung from the ceiling in medieval churches. The wheel candlestick of the collegiate church of Comburg with a diameter of five meters showed the twelve gates of the heavenly Jerusalem from a distance and, equipped with 48 candles, was probably the only source of light in the Romanesque church. By conceiving of the total work of art church building as an image of the eternal Jerusalem, it assumes a relieved, timeless state of being and goes beyond the purpose of a meeting room for the community of believers.

Since the 6th century, towers have shaped the appearance of church buildings in the West, so that in the early Middle Ages church towers gradually gained a similar importance as the domed roofs over the central structures of the Byzantine churches. Two church towers either overlook the eastern part of the church, where they take the position of the dome over the early Christian domed basilica, or they flank the portal on the west side like a city gate. The result was a symbolic sky castle, which formed a protection against the evil forces invading from the pagan west. For the Romanesque churches of the 11th and 12th centuries, the epithet "Himmelsburg" is documented in many literary terms. This does not mean that the earthly western buildings were actually intended for defensive purposes; Whether they should serve symbolically to ward off demons, as the occasional dedication to the Archangel Michael suggests, has been widely accepted, but is also not clearly verifiable.

From the second half of the 11th century, double tower facades occur mainly in Normandy and the Upper Rhine region. As the oldest surviving church building in the Romanesque, in which the twin towers are built typically on the west facade and in the whole building, the former Benedictine monastery church are St-Etienne de Caen and the adjacent convent Ste-Trinité in the northern French town of Caen , with its Construction was started in the 1060s. At St-Étienne the towers already delimit a straight west facade and do not protrude beyond the side walls, while the towers of Ste-Trinité form separate structures protruding to the west and from the sides. The west facade, which was added to the monastery church of St. Mexme in Chinon a few years earlier, from 1050, still has largely independent towers that protrude far beyond the north and south sides. Following the example of St-Étienne, the west facade of which is known as the oldest “harmonious” double tower facade ( façade harmonique ), the characteristic Romanesque façades were created in Normandy and, from the second half of the 12th century, the first Gothic double tower facades in northern France. This statement goes back to Marcel Anfray (1939) and is widely accepted to this day.

A façade harmonique is characterized by a vertical, three-part facade structure that separates the area of the side towers from the gable side of the nave in the middle. This distinguishes it from the west building and the special shape of the Saxon West Bar , a closed transverse building with clearly separated bell tower attachments (or an attached central building). Such a double tower facade became the architectural standard in the Gothic period. St-Étienne de Caen was less suitable as a direct model, however, because the towers do not rise straight and slim from the ground, but only begin above a blocky substructure that creates a horizontal tripartite division of the tower into substructure, shaft and roof peak.

The description of the facade does not say anything about the layout and function of the rooms behind the west facade. It can be a westwork with galleries for the ruler or an extension of the basilica nave. The latter is the case with St-Étienne de Caen, which manages without a gallery in the west and in this respect precedes the Gothic cathedral of Reims from the second half of the 13th century, which has neither side galleries nor a gallery in the west. In Reims, the towers above the rear end of the aisles can only be guessed from the fact that the two western pillars of the central nave are thicker and the arcade distance to the west wall is slightly larger.

Development since the Romanesque

On the way to the harmonious double tower facade, a predecessor of today's Strasbourg Cathedral , which was built between 1015 and 1028 and was the same size as the later cathedral, is located before St-Étienne de Caen. While Ernst Gall spoke out in favor of a double tower facade in this construction phase of the Strasbourg cathedral in 1932, Hans Reinhard also wanted to reconstruct a single central tower above the portal in 1932, which should have corresponded to the St. Thomas Church in Strasbourg. Reinhard particularly refers to a Strasbourg coin from 1249, which shows a church facade with a tower. According to Herwin Schaefer, however, it hardly depicts the cathedral and does not question the older reconstruction theory of this building with its double tower facade. Another cathedral with a double tower facade, of which only the lower part of the north tower is preserved today, was the second building of the Basel Minster (Heinrichsmünster), which was inaugurated in 1019. After a fire in 1185, a late Romanesque new building was built over the ruins. From the preserved north tower (Georgsturm), it is very likely that a double tower facade exists. The abbey church of St-Philibert in Tournus was inaugurated in 1019, and its strict western building with two towers has a defensive character typical of the early Romanesque period.

The ruins of the Limburg monastery in the Palatinate Forest could have had another double tower facade from the first half of the 11th century . The basilica there was built from 1025 to 1042, damaged in 1376 and finally destroyed in a fire in 1504. The remnants of the wall that remained at that time stand upright in a partially restored condition. On a slightly smaller scale, especially in the west, the basic plan shows similarities in form with the Strasbourg cathedral, so that Herwin Schaefer follows the result of the architect Wilhelm Manchot in his monograph Limburg Monastery to Der Haardt (1892) and considers a double tower facade to be possible. The other possible attempt at reconstruction is a west transverse building with a wide central tower. In contrast, the Speyer Cathedral , built around the same time (1030-1066), undoubtedly had such a central tower. Its west facade, which is visible today, largely corresponds in shape to the original building.

The former Romanesque double tower facade is no longer recognizable in the current baroque appearance of Einsiedeln Abbey , which dates from the 17th and 18th centuries. The Romanesque basilica was built between 1031 and 1039. This can be seen from a plan and drawings from 1633, which obviously show the Romanesque architecture that had been preserved until then. The ruins of the collegiate church of Hersfeld Abbey still have the entire southern tower of the western facade. The new Romanesque building began in 1038 after a fire, and in 1071 the nave was used for church services. The original shape of the double tower facade in the west was changed by a renovation in the 12th century and can no longer be clearly reconstructed. During excavations a few meters away, the foundations of the Carolingian predecessor building from 831 to 850, which must have already had two towers on the west side, came to light.

The first building of the Basilica of St. Kastor in Koblenz was built between 817 and 836 as a Carolingian hall church. The square towers in the west, which were added around 1100, are very close together, the west facade is narrower than the nave, which was expanded into a basilica in the 12th century. The west facade of the St. Florian Church, also built around 1100, is an imitation of the twin towers of St. Kastor, which confirms their existence around this time. In the Würzburg Cathedral , the narrow double tower facade, which was begun in the first half of the 11th century, is dominated in a comparable manner by a later nave.

One of the double tower facades of the second half of the 11th century on the Upper Rhine is that of the All Saints Monastery in Schaffhausen , whose cathedral was inaugurated in 1064. The appearance of the original west facade is controversial because the entire building was demolished at the end of the 11th century in favor of a larger new building. A possible reconstruction is only possible on the basis of the plan and the examined foundations. A westwork with a wide central tower or a double tower facade were discussed. Hans Reinhard advocated the first option in 1935, after he had discussed a transition step between the westwork and the double tower in 1926. The majority of the researchers had previously spoken out in favor of twin towers because of the massive lateral foundations in the west.

From the start of construction in 1054 to the inauguration in 1089, the new Romanesque building (Rumoldbau) of the Konstanzer Münster was initially without towers. Around 1100 people began to erect two towers to the west of the entrance hall. Only the north tower dates from Roman times, the south tower was not completed until 1378 after collapsing twice.

In the Hirsau Monastery in the northern Black Forest , the Romanesque building of St. Aurelius II was built between 1059 and 1071 with two massive towers on its west side. Hans Reinhardt did not want to see these towers either, although the west side has been preserved up to the level of the arcade arches and including the tower stumps. From 1082, the church building in the monastery complex, which had become too small, was replaced by a new monastery on the opposite side of the Nagold with the new St. Peter and Paul Basilica. After their inauguration in 1091, St. Peter and Paul had an open courtyard in front of the nave and in front of it were two square towers in the west. A two-tower facade was built by 1120, but it remained unfinished. Later these were connected to the nave with a porch. Of St. Peter and Paul, only the north tower (Owl Tower) stands upright today, the position of the south tower can be seen from the lower rows of stones. The model for this architecture, realized for the first time in Germany, was the Abbey Church of Cluny in the building phase Cluny II, begun under Abbot Maiolus before 963 and inaugurated in 981. Cluny II was from the end of the 11th century to the beginning of the 12th century by the 187 meter long Replaces the successor building Cluny III, whose double tower facade forms a counterweight to the wide choir. In the older St. Aurelius Church, the towers were integrated into the structure according to the classic double-tower facade; under the influence of Cluny II, independent tower structures were realized, which was a parallel conception at that time.

Little known is the former Benedictine abbey of Sant'Urbano all'Esinante, which is located in the central Italian region of Marche near the city of Jesi in the area of the village of Apiro . Construction began around 1070 and was completed around 1100. The altar was consecrated in 1086 with inscriptions. The basilica has three semicircular apses protruding from the east wall and a compact west building that towers above the nave and is flush with the longitudinal walls. The building has been restored, the presumably existing towers above the west building are missing. A double tower facade is considered likely because the arcades in the west were lined with massive partition walls, creating three square rooms in the west.

The oldest preserved church building with a double tower facade in England is Westminster Abbey , which was built from 1045 and in 1065, at least in the eastern part, was completed to the point that a dedication ceremony could take place. The entire building may not have been completed until the first half of the 12th century. The west facade of this construction phase could only be deduced from images and soil investigations. According to this, the towers protruded beyond the longitudinal walls and rested with the inner corners on mighty pillars, the distance between them being wider than the other arcades.

In 1093 the Romanesque construction of Durham Cathedral began. Her square towers also protruded beyond the plan. For this and the Norman-style cathedrals built in England in the following decades , Westminster Abbey, whose models in turn came from Normandy, served as the starting point. Examples of this are, in addition to Durham, the construction of Southwell Minster and Worksop Priory in Worksop ( Bassetlaw District ) from the same period, which began in the early 12th century .

The Romanesque forerunners of the Gothic Canterbury Cathedral and the Abbey of St. Augustine in Canterbury have almost completely disappeared. After a fire in 1067 that destroyed the Anglo-Saxon church, the rebuilding of Canterbury Cathedral began in 1070 under Bishop Lanfrank , which was largely completed by the end of the 1070s. Numerous expansions and alterations followed over the next few centuries. From the Romanesque construction phase, only the north tower remained until 1832, when it was renewed in the shape of the south tower. Before it was destroyed, the architect JC Buckler made detailed plans and view drawings, which enabled the Romanesque west facade to be reconstructed. The tower was laterally bounded by corner pilasters and divided into seven floors by narrow cornices. The two upper floors jumped back slightly. The lower half of the tower only had a round arched window on the second and fourth floors, and above that there were two rows of window openings in double arcades. The top floor was formally different with two windows framed by pointed arches. The cathedral and the abbey of St. Augustine, also begun around 1070, are among the first church buildings after the Norman conquest of England in 1066. Because Lanfrank had previously been abbot in the monastery of St-Étienne in Caen from 1063 until his arrival in England, it was over the narrow Connections and roughly parallel construction times of both churches are speculated. In terms of facade design, however, there was almost no similarity between the two churches.

The knowledge of the Romanesque double tower facade of the Abbey of St. Augustine is also based on representations from the 19th century. Until its complete collapse in 1822, the north tower ("Ethelbert Tower") stood upright as a ruin. Sketches from the time before the collapse show a six-story tower that, according to style analyzes, was built in the 1120s. The construction of the nave lasted from 1070 to the 1090s. Each floor was - more lavish than in Canterbury Cathedral - filled with a triple window in a large arched field. The specialty of these towers was their alignment with the interior. The inner corners rested on pillars that were thicker than the arcaded pillars of the central nave, but the same distance apart as those. St. Augustine was probably the first church building whose towers were completely integrated into the basilical plan.

In the case of Durham Cathedral , the towers appearing as mighty bulwarks are integrated in the interior of the basic plan of the nave. The bundle pillars on which the inner tower corners rest break through the constant alternation of columns and bundle pillars of the rows of arcades, because two massive bundle pillars follow one another at the west end. On the outside, the towers protruding from the longitudinal walls take over the horizontal structure of the nave with the row of windows in the prayer room, gallery window and upper balcony. The nave and westwork seem to have been built at the same time from around 1104 because of the identical facade design. Thus Durham Cathedral may have served as a model for Westminster Abbey, whose alternating arcade columns are designed even more sophisticated. Its west side is the first preserved double tower facade in England, which has all the characteristic features.

In contrast to the well-preserved Durham Cathedral, only the lower area of the north tower of Chester Cathedral, which was begun around 1093 and changed into the 16th century, dates from Romanesque times. Its construction began around 1130, when Durham Cathedral was already completed.

The two church buildings in Canterbury have already formed the essential elements of the Gothic façade harmonique and precede the cathedral of Saint-Denis in time. Because of its choir, which was built between 1140 and 1144, it is regarded either as a preliminary stage to the Gothic cathedrals or as the first real Gothic building. However, the stylistic assessment does not refer to the west side. There, Saint-Denis ends with a westwork that is optically separated from the nave. The west facades of the cathedrals of Canterbury and Durham in England and, in Normandy, the facade of the Ste.-Trinite of Caen come into consideration as a preliminary stage of the Gothic twin-tower facade.

The large Gothic cathedrals generally took over the double tower facade and, with their universal influence, shaped the entire church architecture of the following epochs up to the 20th century. Cathedrals, large monastery and collegiate churches preferred the double tower façade, while some more important bourgeois parish churches also left it with a medium-sized single tower, such as the Freiburg Minster , the construction of which began around 1200, or the Ulm Minster , built from 1377 .

precursor

Syrian tradition

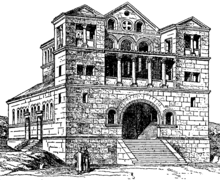

Since the investigations by Melchior Comte de Vogüé in the area of the Dead Cities in Syria in the 1860s, there has been speculation about the influences of early Christian Syrian churches on Romanesque architecture. The Syrian church most frequently mentioned as a possible model for double tower facades is Deir Turmanin from the end of the 5th century. The building had almost completely disappeared by 1900 and is only known from illustrations published by Melchior Comte de Vogüé. The basilica of Qalb Loze from the 460s and the wide arcade basilica of Ruweiha from the second half of the 5th century had a similar representative façade formed by two towers . Their style-shaping influence shone as far as Armenia, where the double tower facade can be found on the unique basilica of Jereruk from the 5th or 6th century.

Hermann Wolfgang Beyer traces the Syrian two-tower facade back to its presumably distant archetype, the pylon (gate construction) of Egyptian mortuary temples and the entrance facade of the ancient oriental house type Hilani . Beyer also counts other Syrian church ruins among the creative redesigns of the ancient tower facades, which are so poorly preserved that it cannot be said with certainty whether they had double tower facades, such as the basilica in as-Suwaida from the 5th century and the church of il -Anderin (in antiquity: Androna) near Chalkis , who possibly had four towers (two above the apse side rooms in the east).

Due to its proximity to the pilgrimage destination Jerusalem, Syria could have been in contact with the West in early Christian times. Richard Krautheimer recognizes a fundamental influence from Asia Minor, the Middle East and North Africa on early medieval central European church construction. Not the Roman basilica of the 4th century but, for example, the small early Byzantine churches of Binbirkilise in Anatolia were models for the French churches of the 6th and 7th centuries. The time gap between the Middle Eastern churches of the 6th century and the earliest surviving Central European churches with double tower facades from the 11th century has to be bridged in the meantime by looking for evidence of lost buildings. A church in the Abbey of Saint-Martin d'Autun , which is dated to the end of the 6th century, is said to have had two towers according to the interpretation of plans and descriptions from the 17th and 18th centuries. The Carolingian forerunner of the Cathedral of Saint-Denis , carried out under Abbot Fulrad , was inaugurated in 775. Until the first half of the 12th century it had two low towers on the entrance side, at last in a ruinous condition, as Abbot Suger complained, who directed the demolition and the new building. The new building of the Basilica of Saint-Germain d'Auxerre , inaugurated in 865, also had two towers. The northern tower and the associated narthex existed until 1820. The southern tower had to give way to a larger tower in the 12th century, which has remained free-standing to this day. The Carolingian Salvatorkirche , construction phase 3 of the Imperial Cathedral in Frankfurt / M., Was completed in 874. The west building was formed by two square bell towers and two round stair towers in between. The portals were not on the west, but on the north and south sides of the square towers.

Westwork

The westwork as a defined, independently erected transverse rectangular structure in the west of the nave represents, according to a common view, the decisive preliminary stage for the development of the harmonious double tower facade. It flourished in the Carolingian and Ottonian times . The term "Westwerk" was coined in 1889 by Josef Bernhard Nordhoff, who wanted to express the defensive character of this building section with the word component "Werk" corresponding to " Vorwerk ". Nordhoff defined the westwork as “a high bell and middle house with its own roof, bounded by the flank towers” and introduced the theory of the development of the double tower facade from the westwork. Wilhelm Effmann transferred the concept of the westwork to the Carolingian building of the Saint-Riquier (Centula) monastery . The presumed reconstruction of Saint-Riquier, based only on written records (especially the chronicle of the monk Hariulf from 1088), as it was done by Effmann, was declared the starting point for a whole series of western buildings. Since then, there has been controversial discussion about the importance and the basic structural idea of the westwork. Further Carolingian westworks characterize the western view of the Corvey Abbey Church and Aachen Cathedral . As a result, the west works were separated from the west choirs as mighty entrance buildings with usually three towers, which had no entrances.

In Romanesque architecture, the Carolingian type of the westwork may have developed into double-tower facades, three-tower systems or porches with a single tower. It is widely believed that its original function was a separate chapel above the main entrance, usually dedicated to the demon-warding Archangel Michael as the keeper of the gate. Furthermore, possible functions of the upper floors in the west works were a separate room for the ruler to attend church services, a baptistery, parish church or a room for court hearings under the chairmanship of the bishop.

A special case is the origin of the double tower facade from the end of the 10th century at the collegiate church St. Peter in Bad Wimpfen . It originally belonged to a twelve-sided central building that was converted into a basilica in the early Gothic period.

See also

literature

- J. Philip McAleer: Romanesque England and the Development of the Façade Harmonique . In: Gesta , Vol. 23, No. 2, 1984, pp. 87-105

- Herwin Schaefer: The Origin of the Two-Tower Façade in Romanesque Architecture . In: The Art Bulletin , Vol. 27, No. 2, June 1945, pp. 85-108

- Heiko Seidel: Investigation of the history of the development of sacral western building solutions in the core Saxon settlement area in the Romanesque period, mainly illustrated using the examples of the Marienmünster monastery church and the parish church of St. Kilian zu Höxter. (Dissertation) University of Hanover 2003

- Keyword facade. In: Reallexikon zur Deutschen Kunstgeschichte , Vol. 7, Munich 1978, Sp. 566 , 572

- Keyword Westbau. In: Ludger Alscher (Ed.): Lexicon of Art . Vol. 5, Verlag Das Europäische Buch, Berlin 1981, p. 579

Individual evidence

- ^ Günter Bandmann: Medieval architecture as a carrier of meaning. Gebr. Mann Verlag, Berlin 1951, pp. 65, 92f

- ↑ Claus Bernet: Heavenly Jerusalem in the Middle Ages: Microhistorical ideal and utopian attempt at implementation. In: Mediaevistik , Vol. 20, 2007, pp. 9–35, here pp. 16f

- ↑ Hans Sedlmayr : The development of the cathedral. Atlantis, Zurich 1950, pp. 112f, 115

- ↑ Hans Sedlmayr, p. 121

- ↑ Heiko Seidel, 2003, p. 105

- ↑ Marcel Anfray: L'architecture Normande, son influence dans le nord de la France aux Xl et XIIC siecles. Paris 1939, pp. 235f

- ^ J. Philip McAleer, 1984, p. 87

- ↑ J. Philip McAleer, 1984, pp. 88f

- ↑ Herwin Schaefer, 1945, pp. 87–91

- ↑ Herwin Schaefer, 1945, pp. 92f

- ↑ Herwin Schaefer, 1945, pp. 93f

- ^ Hans Reinhardt: The first minster in Schaffhausen and the question of the double tower facade on the Upper Rhine. In: Anzeiger für Schweizerische Altertumskunde, Volume 37, Issue 4, 1935, pp. 241-257

- ↑ Hans Reinhardt, 1935, p. 249

- ^ Hans Erich Kubach: The pre-Romanesque and Romanesque architecture in Central Europe . In: Zeitschrift für Kunstgeschichte, Volume 18, Issue 2, 1955, pp. 157–198, here p. 191

- ↑ Herwin Schaefer, 1945, pp. 95f, 104f

- ↑ Hildegard Sahler: The abbey church of Sant'Urbano all'Esinante in the brands. In: Mitteilungen des Kunsthistorisches Institut in Florenz, Volume 47, Issue 1, 2003, pp. 5–56, here p. 25

- ↑ J. Philip McAleer, 1984, pp. 91f

- ↑ J. Philip McAleer, 1984, pp. 93-95

- ↑ J. Philip McAleer, 1984, pp. 98f

- ^ J. Philip McAleer, 1984, p. 100

- ↑ Melchior Comte de Vogüé: Syrie centrale. Architecture civile et religieuse du Ier au VIIe siècle. J. Baudry, Paris 1865-1877, Vol. 2, Plates 130, 132-136

- ↑ Louis Grodecki: Introduction . In: Harald Busch , Bernd Lohse (Ed.): Pre-Romanesque art and its roots. (Monuments of the Occident) Umschau, Frankfurt / M. 1965, p. XVII

- ↑ Christina Maranci: Medieval Armenian Architecture. Construction of Race and Nation . (Hebrew University Armenian Studies 2) Peeters, Leuven u. a. 2001, p. 199

- ^ Hermann Wolfgang Beyer: The Syrian church building. De Gruyter, Berlin 1925, p. 149

- ↑ Herwin Schaefer, 1945, p. 102

- ^ Richard Krautheimer: The Carolingian Revival of Early Christian Architecture . In: The Art Bulletin, Vol. 24, No. 1, March 1942, p. 4

- ↑ Herwin Schaefer, 1945, pp. 102f

- ↑ Josef Bernhard Nordhoff: Corvei and the Westphalian early architecture. In: Repertorium für Kunstwissenschaft, XII, 1889, p. 380; quoted from: Herwin Schaefer, 1945, p. 105

- ^ Wilhelm Effmann: Centula - St. Riquier. An investigation into the history of church architecture in the Carolingian era. Munich 1912

- ↑ In summary: Irmingard eighth: On the reconstruction of the Carolingian monastery church Centula. In: Zeitschrift für Kunstgeschichte , Volume 19, Issue 2, 1956, pp. 133–154

- ↑ Rudolf Koch: The development of the Romanesque west tower complex in Austria. (Dissertation) University of Vienna 1986, p. 40 (Chapter: The Carolingian Westwork. )

- ↑ Heiko Seidel, 2003, p. 17

- ↑ Herwin Schaefer, 1945, pp. 105f