Dead cities

Dead Cities are the ruins of the formerly around 700 village settlements from the late Roman and early Byzantine times in the north Syrian limestone massif. The heyday of the settlements began in the 4th century AD and was based on the cultivation and marketing of olives, wine and grain. The Greek- speaking landowners invested the income from the predominantly feudal social order in magnificently designed villas , public buildings and, above all, in churches made of solid limestone. Most of the residents converted to Christianity in the 4th century . In the area of the Dead Cities, the development of Syrian church construction took place from the simple village house church to the city cathedral . At the beginning of the 7th century, before the Arab conquest , the economic decline began for reasons that can only be guessed at. In the two centuries that followed, the villages were gradually abandoned.

location

The northern Syrian limestone massif covers an area of around 5500 square kilometers and is around 140 kilometers long in a north-south direction and 40 to 50 kilometers wide from east to west. It is bordered in the north by the fertile Afrin plain and in the south by the Nahr al-Asi (Orontes). In the west the area is separated from the mountain range of the Jebel Ansariye by the wide valley of the Ghab through which the Orontes flows, while in the east it gradually merges into the great inner Syrian plateau. The main road between Hama and Aleppo via Maarat an-Numan , which was already important during the Ottoman period, runs in the arable plains of the old Syrian settlement area. All major cities lie along this line.

geography

The northern Syrian limestone massif consists of an average of 400 to 500 meter high chains of hills with some over 800 meter high peaks, which are interrupted by inland plains. It is divided into a northern, central and southern region. In the north are the Jebel Siman (east of the Dar Taizzah - Basuta - Afrin road ) and the Jebel Halaqa (around Dar Taizzah). The three middle mountain ranges are from west to east: the north-south running along the Orontes mountain ranges from Jebel Dueili (Duwayli) and Jebel Wastani (in the south to Jisr asch-Shugur ), Jebel il-Ala (around Qalb Loze ) with the 819 Meter high Teltita as the highest peak and in the middle in the east the 400 to 500 meter high Jebel Barischa with the dead city of the same name . The highest peaks are in the southern part of the limestone massif, the Jebel Zawiye (also Jebel Riha). The mountain Nebi Aiyub (two kilometers east of Juzif ) reaches 937 meters here, a few kilometers south another peak is 876 meters high.

The crusted and karstified hill plateau is sparsely populated and can only be used extensively for agriculture ; In addition to olives and, in a few regions, grapes, wheat and barley are mainly grown in the winter months. On the other hand, the partly wide inland valleys are clearance zones with often deep and fertile dark red limestone soils ( Terra Rossa ). In the summer dry season, the landscape is characterized by the contrast of colors between red earth and gray-blue limestone. In spring the karst hills are covered with green grass and wild flowers. The limestone massif is a specialty of Western Syria. It is geologically formed by the upturned western edge of the northern Syrian table. Only here do the Eocene and Miocene emerge in a tectonically elevated layer of 200 to 400 meters thick bench limestone , which slopes down relatively steeply to the Orontes and Afrin.

Despite abundant rainfall in the winter months, there are no rivers in the area and there are only groundwater wells in the valley floors. The inhabitants of the villages on the hills have adapted to these ecological conditions since ancient times by building cisterns. Back then, the mountainous area was not significantly more forested than it is today, but a layer of loose soil may have been lying over the now eroded limestone surfaces. In some depressions, pump irrigation from the groundwater also enables vegetables to be grown in summer.

history

“Dead Cities” is a term coined by Joseph Mattern after a trip in the late 1930s (French: “villes mortes”). The formerly around 700 settlements, another count comes to 820, were built and inhabited in the period from the 1st to the 7th century. The oldest buildings are only passed down through inscriptions and small remains. From the first incursion of the Sassanids in 573 under Chosrau I into the rural regions of the limestone massif, the inhabitants were able to partially recover. Even with the Persian and Arab conquest of the Roman eastern provinces in the first half of the 7th century, the villages were not destroyed. There followed a gradual emigration of Christians, which dragged on over several generations and the reasons for which there is no certainty. In the 8th century most of the villages were deserted, only a few were still inhabited until the 10th century.

In ancient times the area was called Belus and was surrounded by the cities of Apamea and Antioch on the Orontes, as well as by Kyrrhos to the north and Haleb to the east . Apameia was the administrative center for the southern part (Apamene), Antioch for the northern part (Antiochene) . At that time, only three settlements within the mountain range can be described as cities. The largest city was Al-Bara , the ancient Kapropera, Deir Seman (Telanissos) was a pilgrimage city below the Simeon monastery and Brad (Kaprobarada) was the administrative center of Antiochene in Jebel Siman, which flourished in the 6th century. The rest were bigger and smaller villages. But even settlements with fewer than 50 houses had a parish church in the center and perhaps two churches or a monastery complex on the outskirts.

There are individual finds from the Hellenistic period, otherwise the earliest excavation finds date to the 1st century AD. The oldest dated inscription comes from the year 73/74 AD and was found in Refade (plateau of Qatura near Dar Taizzah) . 35 inscriptions date from the 1st to 3rd centuries. Most of the inscriptions were in Greek , some in Old Syriac . The oldest Christian inscription dates from 326/327. Around the middle of the 4th century the city of Antioch had become predominantly Christian, in the rural regions there were probably still followers of the Roman and Hellenistic cults until the end of the century; until Emperor Theodosius (347–395), at the end of his reign, ordered the smashing of pagan cults and the temples destroyed. As a sign of triumph over the ancient faith, churches were built on the site of the temples.

After 250 to 300, the forms of architecture became impoverished, probably due to external political causes. The conquest of Antioch by the Sassanids in 256 could have had an indirect effect on rural areas. The second possible explanation is a plague epidemic that spread over 15 years in all Roman provinces. The economic boom and the expansion of the settlements took place in the 4th century. The heyday, from which most of the surviving building remains come, was from the 4th to the 7th century.

Research history

The good state of preservation of many villages aroused astonishment when they were rediscovered in the 19th century. In 1903, for example, the American theologian Thomas Joseph Shanan headed the relevant chapter in his history of early Christianity with “A Christian Pompeii ”.

The first scientific investigations of the ruins were carried out in the 1860s by Charles-Jean-Melchior de Vogüé , who later became the French ambassador of Constantinople. They were published from 1865 to 1877 together with the drawings by his architect Edmond Duthoit. From 1899 to 1900, Howard Crosby Butler undertook a detailed recording of the material during an expedition commissioned by Princeton University , which was published in 1903. A summary of his further travels in 1905 and 1909 was not published until posthumously in 1929. The architect Georges Tchalenko restored the Simeons monastery from 1935 and published "Villages antiques de la Syrie du Nord I-III" in Paris from 1953 to 1958, in which he presented a historical development of the settlements based on an olive monoculture. In the 1970s and 1980s, the French Archaeological Institute carried out excavations in Damascus . Under the direction of Georges Tate and Jean-Pierre Sodini, excavations were carried out in Dehes and subsequent investigations at 45 other locations. Tate chose Dēhes as an example of a large settlement with no special features to research the social and economic conditions of the Dead Cities.

Christine Strube worked on architecture and building decoration from 1977 to 1993 and specified the dates of the church buildings by comparing styles .

Ancient economy

Hundreds of oil presses have been preserved from the early Byzantine period . Olive groves were created in monoculture and provided the livelihood of the villages. The income was given to trade caravans or sold in the nearest towns. To a lesser extent, the villagers also cultivated wine, at least on the Jebel Zawiye in the south . Grains and vegetables grew on the plains, according to some inscriptions. The stone cattle troughs, many of which have been preserved in the houses, indicate the keeping of cows, sheep and horses. Another source of income for places on the roads connecting the Orontes Valley and the eastern inland was participation in long-distance trade. In the 5th century, pilgrimage tourism was an economic factor for numerous churches and monasteries, especially in the north.

The inhabitants were made up of landowners, tenants and hired farm workers. The feudal lords often lived in the city, their country estates (Epoikia) were mainly near the big cities and were worked by dependent farmers. On the other hand, Komai villages were more in the hinterland and whose land was worked by free farmers who paid taxes. Parts of the land were leased to officials and soldiers for special services. There was a special form of contract between landowners and farmers in which the tenant undertook to work in the fields or in the olive groves for a contract period of several years and after the specified time (for olives until the first harvest maturity) farmed half of them Got land as property. Large pieces of land were divided into smaller parcels and these were marked by a network of rows of stones.

The olives were crushed in a first step using stone rollers that were moved in rock pools. Then the olive mash was pressed with stone weights attached to long wooden poles. The oil presses belonged to individual houses, larger of these structures, which weighed tons, were used collectively. The olive harvest in October and November and the subsequent processing into oil were labor-intensive and required the cooperation of the entire population. It took four to five months of work a year to grow olives. The planting of olive groves made it necessary for the farmers to have interim financing because of the long time from planting to the first harvest, which took 12 to 15 years. The large number of oil presses found shows the former wealth of the villages. There are 56 known oil presses in Jebel Siman, 157 in the central area and 36 in Jebel Zawiye.

Reasons for leaving the settlements

Different assumptions have been made about the reasons for the economic decline and the almost complete emigration of the population by the 10th century. The notion of an elegant and cultivated society of landed aristocrats who commanded an army of slaves in the fields and who ultimately fled the plague of Islamic intruders only gave way after the knowledge gained around 1900 that many places in the central region were still populated in the 8th century. Butler blamed environmental changes such as soil degradation. In the middle of the 20th century, Tchalenko saw a socially and economically more differentiated society, in which a gradual fragmentation of large estates into small farms had taken place. According to Tchalenko, the economic decline began in the early 7th century when trade to the west was interrupted by the Persian occupation. Most of the olive oil by then had been brought to the port of Antioch and further exported to the Mediterranean region.

The demand for olive oil may also have declined because oil was replaced with wax as a lamp fuel . As a result, there would no longer have been sufficient purchasing power from oil exports for the necessary import of daily consumer goods. This is countered by the fact that the export of olive oil was only one of the sources of income and the self-sufficiency through grain, wine and fruit growing as well as cattle breeding was also of economic importance. It is not clear why the population did not have the opportunity to continue to exist as a more modest self-sufficiency in Arab times. Perhaps they did not want that, because in the plains previously torn and depopulated by wars, farmland had become free further east, where there were now simpler living conditions.

Going further than Tchalenko and in contradiction to de Vogüé, Georges Tate described only small houses of simple farmers and the settlements as a community of self-organizing workers. The large "villas" were farmhouses shared by large families. He considers economic reasons in connection with ecological deterioration to be decisive for leaving the region. He saw the oversized population growth in the sense of Malthus' theory of the population trap with simultaneous soil degradation leading to decline.

Designs

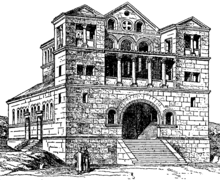

In contrast to the systematic and right-angled Roman cities, the villages in the limestone massif grew haphazardly and show no orderly structure. There were no urban meeting places such as agora , amphitheater or the hippodrome . The vast majority of the buildings were residential buildings, which often differed from public buildings only in individual decorative elements. The financial assets of the client were decisive for the quality of the masonry and the selection of the form elements. The production of monolithic round pillars on the entrance side required considerably more working time than square posts. The same applies to the reveals of the entrance door, some of which are elaborately decorated in relief. All the buildings were made of more or less carefully assembled limestone without joints and mostly covered with a gable roof made of wooden beams with roof tiles. The walls of the first houses consisted of irregular cuboids as double masonry, in the 5th and 6th centuries the houses were mainly made of simple orthogonal masonry with even horizontal layers and were thus better preserved.

Residential houses

Simple basic forms of residential buildings were repeated over a long period of time. The houses were two-story, in some exceptional cases three-story and rectangular in an east-west direction. They had a wooden gable roof . An open vestibule ( portico ) was built on the entrance side in the south , which was supported either by pillars , columns or a combination of pillars on the ground floor and pillars on the upper floor. The type of village house differed fundamentally from the peristyle houses of the northern Syrian cities. Cattle sheds were often found on the ground floor and living rooms on the upper floor. The houses usually had two to six, more rarely and only in the south up to 13 rooms. The residential building was part of a property and stood in the middle of a courtyard, which was surrounded by a high wall and on the outer walls of which there were simple outbuildings. The courtyard gate could be simple or representative.

In terms of the basic plan and decoration, residential houses can hardly be distinguished from communal houses ( Andron ) . Andron occupied a central location within the village and were not surrounded by their own courtyard. There was a large room on the upper floor that was used for all kinds of meetings. Other community buildings that existed in some villages were accommodation for travelers (Xenodocheia), guest houses (Pandocheia) and public baths ( thermal baths ) . The ornamental design of the houses, especially the column capitals followed the development of the church. On some secular buildings, the structuring of the outer wall surfaces by means of profile bands was adopted from church models. The best examples of the facade structure of manorial houses can be found in Serjilla and on three buildings in Dalloza. Both places are in the Jebel Zawiye.

The function of the many preserved tower houses has not yet been fully clarified. They were additions to houses within the villages like in Jerada , shaped the west side of churches as two towers or stood outside in the fields. They could have served as a warehouse or for surveillance. Free-standing towers in the remote mountain region, where attacks from nomads were seldom expected, could also have been places of retreat for hermits and monks. This would be conceivable for the tower in Refade in the vicinity of the stylite cult of Symeon .

Church buildings

According to archaeological findings, the first Christian services in the limestone massif were held in Qirqbize (near Qalb Loze at the height of Jebel il-Ala) in a rectangular living room converted into a house church in the 3rd century . From the basic form of the Roman house , unadorned one- nave and three- aisled church buildings developed . Like the private houses with their construction plan and later their ornamental design, they were in the tradition of Hellenistic architecture and did not follow the Byzantine tradition of the domed room. The oldest dated church in the region was in Fafertin (in Jebel Siman). A Greek inscription with the year 372 was placed above the eastern south portal.

The majority of the church buildings, which have been preserved from the end of the 4th century, were single-story, only a few had a gallery . According to church law, the orientation of the chancel to the east was prescribed. The most widespread were three-aisled columned basilicas , of which over a hundred are known. The early single-nave churches of the Jebel il-Ala still resembled simple gabled houses . The first great architect named in the founding inscriptions was Markianos Kyris. In the first two decades of the 5th century he was responsible for building four churches in neighboring towns on the northern slope of the Jebel Barischa. His buildings in a simple, clear style include the Eastern Church of Babisqa (courtyard portal from 390, Church 401 completed) and the Church of Paul and Moses in Dar Qita from 418; other inscriptions with his name are undated. They are at the Eastern Church of Ksedjbeh and the Church of Qasr il-Benat (Qaşr el-Banāt, 432). The inscription of the latter church, which was completed by a successor, shows that Markianos Kyris "built it according to a vow" and that he was buried in the apse. It is a sign of the great veneration enjoyed by the master builder, as burial sites were extremely rarely inside churches.

The oldest and at the same time very well preserved wide arcade basilica in Qalb Loze on the Jebel il-Ala dates from the middle of the 5th century. This particular Syrian church style produced spans of over ten meters between the arcades outside the limestone massif. The largest distance between the pillars had the basilica in the temple courtyard of Baalbek and basilica A in the east Syrian pilgrimage site Resafa . The only wide arcade basilica in the south was built around 500 in Ruweiha . The north church of Ruweiha (Bizzos church), in which instead of the slender columns, massive and squat pillars supported the high walls of the central nave, found no imitation in the region.

Very often the addition of side rooms to the semicircular apse was taken over from the Roman temple building, so that the apse was enclosed within the building and not visible from the outside. The east wall was straight on the outside. As with the residential buildings, the entrances were on the southern long side, the west gable was closed as an influence of the house architecture in the churches in the central and northern limestone massif. He was only able to get a door from the 5th century. In the south the west facade of the early churches was opened through a wide door. Single-nave basilicas were added as a regional architectural style in the 5th and 6th centuries. From this, in turn, three-aisled churches with a rectangular chancel instead of the apse developed in the second half of the 5th century. The latest dated church of this epoch in northern Syria and at the same time one of the last in all of Syria was the church of St. Sergios in Babisqa from 609/610.

Most of the churches with a rectangular chancel were in the Jebel Barischa area, and there were also a few in other areas in the north. They were probably developments of the 6th century only for small village churches. All of these churches had a simple pent roof made of a wooden structure on the east wall above the chancel. This type of building includes the western church of Baqirha (inscribed 501), the local eastern church from 546, the church of Hirbet Hasan (Khirbit Hasan, 507) and the Sergios churches of Dar Qita (537) and Babisqa. There are also three wide arcade basilicas.

The most demanding special form of a church apse came from the pilgrim church in Qalb Loze. The otherwise invisible or inconspicuous apse now emerges from the wall in a semicircle and is emphasized by columns that are placed on a surrounding window sill in front of the apse wall. Qalb Loze is the preliminary stage for Qalʿat Simʿan, which was built a little later towards the end of the 5th century . This most important church building in Northern Syria initially continued to work on the Phokas Church in Basufan , which was completed in 491/492 and which also had three two-story columns, which were presented to a semicircular apse wall. It is a rare example of how the same municipal workshop in a village church produced an artistic quality that corresponded to the previously completed large original. The monastery church of Deir Turmanin also had an apse with columns , whereby the pentagonal apse there, as in Basufan, lay between side rooms protruding to the side.

In Deir Turmanin (ten kilometers south of Deir Seman ), Qalb Loze and at the Bizzoskirche in Ruweiha , the only double tower entrance facades in the area of the Dead Cities are found. Two corner towers, together with a narrow vestibule ( narthex ) in between, which towered over the side aisles of the representative basilicas on the west gable, were intended to emphasize the main portal behind a broad arch. The double towers on the churches are a redesign, the design of which goes back to the Hittite court house Hilani in the region and which can also be found on some temple and palace facades in Syria in the Hellenistic period. The development of this type of facade continues from here to European Romanesque .

Graves

The most common form of tomb was the hypogeum , an underground room carved out of the rock with burial niches ( arkosolia ) on three sides and an entrance from the fourth side. The entrance was visible from the outside and in some cases was designed like a temple portal. There were also stone sarcophagi with lids that were placed at ground level; for some the grave was sunk into the rock floor and only the coffin lid remained visible. A canopy on four posts with a pyramid-shaped roof in Brad in the north represents a combination of an underground burial space with a monument visible above ground . The pyramid roof of a tomb in Kaukanaya (south of Qalb Loze ) dated to 384 AD rests on eight stone pillars. In al-Bara, in Ba'uda and in Dana (south) in the south there are square mausoleums with pyramid roofs, the design of which goes back to the Greek mausoleum of Halicarnassus . In Dana (south) a porch covered with stone beams was built, part of which is still preserved, resting on two columns.

liturgy

The church architecture is an expression of faith. The basic functions that it has to fulfill were and are defined. Changes in religious practice can be seen in the structural development. Archaeological studies and the evaluation of contemporary writings show a regional expression of the liturgy in the Dead Cities , the concept of which changed through the encounter with pagan religion and in which the worship of icons as the central part of the Byzantine rite was missing.

The rules of the liturgy saw at the service for the male lay before the right female for the lay the left aisle. In churches with a built-in transverse partition in the main room, the men stood in the eastern part and the women in the western part. They had come in through two separate entrances on the south wall. The eastern entrance for the men often had the more elaborately ornamented door jamb and the lintel with the founding inscription. In addition to gender segregation, there were prescribed places for old and young men and women and for virgins and widows. After the service began, no doors could be opened. After reading out the Holy Scriptures, sermon and prayer, the Eucharist followed as the climax of the divine service only for baptized parishioners .

The clergy sat in the apse, on side benches in front of the apse or on a U-shaped installation ( Syrian bema ) , the straight side of which faced east, in the center of the main nave. The shape and arrangement of these podiums were a specialty developed in the region. The bema, which comes from the Greek tradition, generally referred to a raised podium, in the synagogue a podium ( bima ) moved into the center of the liturgy. Bemata in the northern Syrian limestone massif was only found in the churches of smaller towns; the earliest known was built into Brad's Julianoskirche, dated 401/2 . None of the excavated Bemata was found in an episcopal church. On the stone pedestal of the bema, a wooden throne was placed in the middle to place the gospel and wooden chairs around the outside. From the middle of the 5th century, the Bema seats were made of stone and their number was fixed at twelve. This empty throne in the middle, which was surrounded by twelve seats, formed the ritual center during the word service and should remain free, as it was symbolically intended as a place of residence for Christ as the actual chairman of the service.

From the 5th century there was a liturgical change. Since that time, the entrances to the two side rooms on the side of the apse have differed: The Martyrion ( reliquary chamber ) was now opened to the side aisle through a large arch and was connected to the apse through a door, while the other side room, the diakonicon , was from the nave from further could only be entered through a small door. It is possible that the procession to the altar passed through the arch, which had become part of the service with the introduction of the St. James liturgy . The first church with this innovation is the Eastern Church of Babisqa (dated 401).

There are no indications for the installation of an iconostasis necessary in the Byzantine rite . From the end of the 5th century, however, there were curtains to separate the chancel from the nave and only temporarily open it to the community. Churches were often under the protection of saints , most of whom were martyrs. The most popular was Sergios .

Ruins in the northern Syrian limestone massif

- Jebel Siman and Jebel Halaqa in the north

- Basufan : southeast of Deir Seman. Place with a church from 492, few remains

- Brad (Kaprobarada): former administrative center of Jebel Seman, above Basuta

- Burj Haidar (Kaprokera): three kilometers east of Basufan, several churches

- Deir Seman (Telanissos): pilgrim town with pilgrim hostels and monasteries near the Simeon monastery

- Deir Turmanin : one of the largest basilicas, similar to Qalb Loze, which was almost completely disintegrated around 1900

- Fafertin : oldest dated church in Northern Syria from 372

- Kalota : two basilicas. The western church, completed around 600, shows most clearly the incipient cultural decline

- Kharab Shams : Pillar basilica. Central nave high walls completely preserved, side aisles are missing, therefore referred to as the "stilt church"

- Mushabbak : an isolated columned basilica from the second half of the 5th century

- Kafr Nabu : North of Burj Haidar. Temples and houses from Roman times. Oil press dedicated to oriental deities

- Qalʿat Simʿan , Simeon Monastery

- Refade : Village with heavily damaged residences near Qatura, halfway between the two places is the monastery of Sitt er-Rum

- Simkhar: village with residences and a 4th century basilica

- Central limestone massif

- Ba'uda (Baude): commercial center, residential building with two-story porticos

- Babisqa : Jebel Barisha. Place with two churches

- Baqirha : Place with two basilicas on the north side of the Jebel Barischa

- Barischa : place with residences

- Berriš North : Jebel il-Ala. Last little church in the central limestone massif from the end of the 6th century

- Bettir : Jebel il-Ala. Small early church

- Dana (north) : north of the Jebel Barisha. Roman tomb, the small 5th century church has disappeared

- Dar Qita : former economic center with three basilicas, only a few remains of two

- Dehes : Thoroughly investigated large settlement on the plateau of Jebel Barisha

- Deir Seta : Jebel Barisha. Village from the 6th century with a modern basilica. The only hexagonal baptistery

- Qalb Loze : Jebel il-Ala. One of the best preserved early churches

- Qirqbize : Jebel il-Ala. Oldest house church in Northern Syria, well-preserved houses

- Jebel Zawiye in the south

- Al-Bara (Kapropera): vast city with two pyramid tombs

- Ba'uda (Baude): Place between Serjilla and al-Bara, pyramid tomb

- Btirsa : settlement with a small church

- Dana (south) : pyramid tomb on the east side of Jebel Zawiye, south of Jerada

- Jerada : place with villas and a basilica, two kilometers east of Ruweiha

- M'rara (Meghara): Roman rock tombs with column portico north of Serjilla

- Ruweiha : large wide arcade basilica in the middle of an ancient settlement

- Serjilla : well-preserved settlement from the 5th century

- Shinsharah (Khirbet Hass): settlement with well-preserved villas, a church and a monastery

literature

- Charles-Jean-Melchior de Vogüé : Syrie centrale. Architecture civile et religieuse du Ier au VIIe siècle. J. Baudry, Paris 1865-1877

- Hermann Wolfgang Beyer : The Syrian church building. Studies of late antique art history. Walter de Gruyter, Berlin 1925

- Howard Crosby Butler: Princeton University Archaeological Expeditions to Syria in 1904–1905 and 1909. Division II. Architecture. EJ Brill, Leiden 1907-1949

- Howard Crosby Butler: Early Churches in Syria. Fourth to Seventh Centuries. Princeton University Press, Princeton 1929 (reprinted Amsterdam 1969)

- Georges Tchalenko: Villages antiques de la Syrie du Nord. Le massif du Bélus a l'époque romaine. 3 vol., Paul Geuthner, Paris 1953–1958

- Edgar Baccache: Églises de village de la Syrie du Nord. Album. Planches. 2 vols., Paul Geuthner, Paris 1979–1980

- Clive Foss: Dead Cities of the Syrian Hill Country. In: Archeology, Vol. 49, No. 5, September / October 1996, pp. 48-53

- Christine Strube : The "Dead Cities". Town and country in northern Syria during late antiquity. Philipp von Zabern, Mainz 1996, ISBN 3-8053-1840-5

- Christine Strube : Building decoration in the northern Syrian limestone massif. Vol. I. Forms of capitals, doors and cornices in the churches of the 4th and 5th centuries AD Philipp von Zabern, Mainz 1993; Vol. II. Forms of capitals, doors and cornices from the 6th and early 7th centuries AD. Philipp von Zabern, Mainz 2002

Web links

- Hubert Fehr: A landscape from a bygone era. The dead cities. Archeology online, December 16, 2000

Individual evidence

- ^ Eugen Wirth : Syria, a geographical country study. Scientific Book Society, Darmstadt 1971, pp. 374, 378 f

- ↑ Joseph Mattern: À travers les villes mortes de Haute Syrie. Imprimerie Catholique, Beirut 1933, 2nd edition 1944

- ↑ Strube 1996, p. 2

- ↑ Abdallah Hadjar: The northwest limestone massif and the church of St. Simeon Stylites the Elder. In: Mamoun Fansa and Beate Bollmann: The art of the early Christians. Signs, images and symbols from the 4th to 7th centuries. State Museum for Nature and Humans Oldenburg, Verlag Philipp von Zabern, Mainz, pp. 62–67

- ↑ Beyer, p. 31

- ↑ Strube 1996, pp. 2, 5, 24, 30-31

- ↑ Thomas Joseph Shanan: The Beginnings of Christianity. Benziger Brothers, New York 1903, pp. 265-309 (Chapter: A Christian Pompeii ) Online at Archive.org

- ↑ Aphrodite Kamara: The "Dead Cities" in Northern Syria. In: Mamoun Fansa, Beate Bollmann: The Art of the Early Christians in Syria. Signs, images and symbols from the 4th to 7th centuries. Verlag Philipp von Zabern, Mainz 2008, pp. 39–46

- ↑ Strube 1996, pp. 17, 31

- ^ Warwick Ball: Rome in the East. The Transformation of an Empire. Routledge, London / New York 2000, p. 231 f.

- ↑ Strube 1996, pp. 86-88

- ^ Warwick Ball: Rome in the East. The Transformation of an Empire. Routledge, London / New York 2000, p. 232

- ^ Georges Tate: Les villages oubliés de la Syrie du Nord. Le Monde de Clio

- ↑ Strube 1996, pp. 9-16

- ^ Frank Rainer Scheck, Johannes Odenthal: Syrien. High cultures between the Mediterranean and the Arabian desert. DuMont, Cologne 1998, pp. 293, 315

- ↑ Melchior Comte de Vogüé, 1865–1877, Vol. 2, plates 130, 132–136

- ↑ Christoph Markschies: The ancient Christianity: piety, ways of life, institutions. CH Beck, Munich 2006, p. 177

- ^ Friedrich Wilhelm Deichmann : Qalb Lōze and Qal'at Sem'ān. The special development of northern Syriac late antique architecture. Bavarian Academy of Sciences. Meeting reports, year 1982, issue 6, CH Beck, Munich 1982, p. 4

- ↑ Beyer, p. 45

- ↑ Strube 1996, p. 20

- ^ Peter Grossmann: To the Syrian churches with rectangular altar rooms. In: Ina Eichner, Vasiliki Tsamakda: Syria and its neighbors from late antiquity to the Islamic period. Reichert Verlag, Wiesbaden 2009, pp. 103–111

- ^ Friedrich Wilhelm Deichmann: Qalb Lōze and Qal'at Sem'ān. The special development of northern Syriac late antique architecture. Bavarian Academy of Sciences. Meeting reports, year 1982, issue 6, CH Beck, Munich 1982, pp. 23-25

- ↑ Beyer, pp. 148-153

- ↑ Strube 1996, pp. 19-21

- ^ Frank Rainer Scheck, Johannes Odenthal: Syrien. High cultures between the Mediterranean and the Arabian desert. DuMont, Cologne 1998, p. 313, ISBN 3-7701-1337-3

- ^ Andreas Feldtkeller : The search for identity of the Syrian primitive Christianity. Mission, inculturation and plurality in the oldest Gentile Christianity. Universitätsverlag, Freiberg 1993, pp. 52-55

- ↑ Beyer, p. 33f

- ^ Rainer Warland : Bema . In: Walter Kasper (Ed.): Lexicon for Theology and Church . 3. Edition. tape 2 . Herder, Freiburg im Breisgau 1994, Sp. 195 .

- ↑ Strube 1996, pp. 41-44