Wilhelm Canal

The Wilhelm channel bypassed in Heilbronn the used with weirs and mills Altlauf the Neckar. It was opened in 1821 and since the Middle Ages has been the first opportunity for shipping to navigate the Neckar beyond Heilbronn. The canal was both a shipping route and a port.

planning

Even under King Friedrich (1754–1816), considerations had been made to open up the Neckar, which was no longer passable for ships in Heilbronn since the Neckar privilege from the 14th century, above Heilbronn for shipping. Shortly after taking office in 1816, Wilhelm I commissioned Karl August Friedrich von Duttenhofer to plan a new shipping route to Cannstatt . After protests by the people of Heilbronn, who did not want to do without the centuries-old privilege of stacking money , it was initially planned to have Johann Gottfried Tulla prepare an appraisal before construction began. However, this was delayed by the Baden side because Mannheim also made use of the stacking right and was not interested in this facility in Heilbronn being closed. The later finance minister Ferdinand Heinrich August von Weckherlin finally urged vigorously that Duttenhofer's proposal to build a side canal with a chamber lock bypassing the existing weirs be put into practice, arguing that otherwise important traffic routes might otherwise be relocated to areas outside of Württemberg. The king was convinced and placed the order for the building. No sooner had this order been issued than Tulla suddenly found time for the requested inspection. He did not object to Duttenhofer's plans.

construction

150 fortress convicts from Hohenasperg began work on the construction pit for the lock on March 11, 1819, which was around 70 meters long and 12 meters wide. However, it soon became apparent that the subsoil was not as stable as had been assumed and that pile scaffolding had to be erected. 800 fir supporting piles were driven several meters deep, over which a strong grate made of horizontal framework was placed and bricked up. On top of that, a caulked fir wood covering with a thickness of 16.6 cm was applied, on which the lock walls were built. Ribbed wood lay across the lock walls, lined with rubble in trass mortar; on top came an oak deck floor.

The construction pit had to be kept free of water for seven months. When the water level was low, this could be done with screed pumps , which were operated by 40 men, and a Panster wheel in the Neckar, which drove further pumps. During floods, shovels and 164 men were used to keep the pit dry.

In addition to the pumps, two small cranes manufactured by Grundler in Wasseralfingen were the most important machines in the construction of the chamber lock. They provided valuable services in moving the reed sandstone blocks weighing over five tons , which came from quarries in the area.

The lower layers were walled up with trass mortar, the upper layers with hydraulic lime. In the area of the gates, the walls were secured with a 43 cm thick layer of concrete .

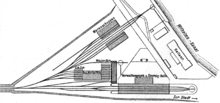

The chamber lock had a length of 37.25 m, a width of 4.60 m and a depth of 2.57 to 4.87 m. It had mortise gates weighing 3.7 tons. The chamber could be filled in eight to ten minutes. During the construction, Duttenhofer adhered to the specifications of Johann Albert Eytelwein . The shipping canal that connected to the lock was about 430 m long and sealed off at the top with an inlet gate that offered protection from floods and ice. The canal had a trapezoidal cross-section and widened at a suitable point into a "ship's container" with a length of 86 m and a width of 16 m. This was equipped with a loading crane and connected to the traffic routes by bridges.

The work under the supervision of Duttenhofer's son August Friedrich lasted 30 months and cost a total of around 171,000 florins. On July 17, 1821, the canal was opened by King Wilhelm and named after him. On this occasion, Duttenhofer was awarded the title of “Commentary of the Order of the Württemberg Crown ”, which was associated with an elevation to the nobility. His son August Friedrich Duttenhofer was able to travel after this achievement.

Later changes

In 1823 the first crane was set up on the Wilhelm Canal. In the years after the inauguration of the canal, shipping up the Neckar increased in volume, even if the loads initially had to be reloaded from the larger Baden to smaller Württemberg ships, because numerous shoals and bottlenecks had to be cleared up to Cannstatt . Before long, an expansion of the Wilhelmskanal was considered.

In 1828, for example, the Royal Customs Directorate advocated the establishment of a watchman with cranes and a customs hall in order to bring together the previously scattered customs facilities in a building directly at the ship's landing stage, thus significantly enhancing the traditional, extremely cumbersome, but certainly profitable for the city, goods handling and customs clearance procedures simplify. Before that, the goods had to be unloaded, brought to the Heilbronn town hall in carts and customs cleared there.

This customs building should either be on the left bank of the Neckar, above the Heilbronn Neckar Bridge, or on the south side of the Wilhelm Canal. At the first location, Duttenhofer feared that the raft traffic would be impeded by ships lying there, while the customs authorities considered this location closer to the city to be advantageous. It was finally agreed on a location on the upper part of the Wilhelmskanal. Duttenhofer worked out a proposal which he presented to the government in February 1829. Once again, the city, concerned about its income, resisted the plans, but was informed on April 9 that Duttenhofer's plans would be implemented at state expense. Under the construction management of Duttenhofer, the new ship container with the Lauer was completed by mid-September 1829. It was 64.5 meters long and eleven meters wide. This offered space for four ships. The associated customs building (Halamt or Hallamt), planned and executed by senior building officer Barth , was completed in 1830. The system was in operation from mid-1831, and ships from Baden went directly to Cannstatt for the first time. In front of the building were two cranes, which in turn came from Grundler in Wasseralfingen. They were built entirely of iron and hand-operated, but represented a significant advance compared to the previously common wooden cranes with treadmills inside, of which there were only two in Württemberg, one medieval in Heilbronn and one from the 18th century in Cannstatt.

An obstacle for shipping was not only the low bridge at the lower end of the canal, but also the lock designed by Duttenhofer, which was too narrow for the larger ships. Removal of the bridge was refused, but an expansion of the lock was discussed. It was initially considered to sharpen the side walls, which would have brought about half a meter of additional width, but then in 1844 the decision was only made to widen the Wilhelm Canal by about eight meters over a distance of 260 meters between the lock and the Kranenlauer near Halamt. This gained twelve berths. The work was headed by the hydraulic engineering inspector Seeger. A new warehouse and a new crane by J. Schweitzer from Mannheim were erected in 1845. This crane with a lifting capacity of 100 hundredweight quickly became a matter of repairs and disputes, but it survived the times, including the bombing of World War II, and is now a technical monument on the right bank of the Wilhelm Canal.

In 1848 the Stuttgart-Heilbronn railway connection was established. The Heilbronn passenger station and the railway site were in the immediate vicinity of the Wilhelmskanal, and in 1849 a large new warehouse was built with a direct railway connection with a turntable . This combination of ship and rail traffic led to an upswing in the Heilbronn transshipment point.

In 1854/55 the Royal Württemberg State Railways built the winter harbor north of the Wilhelm Canal, with which additional berths and loading berths were created for ships. In 1861/62 the winter port was expanded to over double its size with two more port basins, followed in 1875 with the raft port and in 1888 with the Karlshafen.

In 1862 a railway bridge was built over the Wilhelm Canal for the "Kocherbahn" , the railway line from Heilbronn to Hall . Another railway line from Mannheim to Heilbronn made Neckar shipping strong competition from 1869, but this was initially offset by chain towing , which was common on the Neckar from 1878. With this, however, the question of expanding the lock became topical again, which was too small for the larger chain vessels. In 1880 a second, wider lock was therefore planned, which should be parallel to the older one, the König-Wilhelm-Schleuse. In order to be able to erect it, the lock keeper's house and a magazine had to be relocated. The upper canal entrance also had to be expanded. As is so often the case, there was resistance from the city, but construction work began in April 1882 and the new lock was inaugurated on November 7, 1884. In 1897, the Wilhelm Canal was redesigned for the last time with the extension of the ship's container and the Lauers.

The Wilhelm Canal after the opening of the Canal Harbor in 1935

The Wilhelm Canal remained in operation after the opening of the canal port in the new Neckar Canal in 1935, but lost its importance. During the Second World War, the Hallamt, all magazines and loading facilities were destroyed, but the actual canal was preserved. When planning the redesign of the completely destroyed old town of Heilbronn, Prof. Karl Gonser's traffic plan provided for a ring of avenues around the city center. In order to be able to close this ring in the north-west of the city, consideration was given to filling in the Wilhelm Canal at short notice, after considerations about relocating the railway systems there had failed. In the end, both the railway system and the canal were preserved. With the opening of the Neckar Canal section from Heilbronn to Gemmrigheim on September 15, 1952, it had finally served its purpose as a shipping route .

Todays use

After the port of Heilbronn was relocated to the port of the canal, efforts were made to fill in the Wilhelmskanal, but this was averted in 1956; the canal was preserved as a "monument to the economic development of the Neckar" and is now a cultural monument under monument protection. In 1957 it passed from the property of the state waterways and shipping directorate to that of the city of Heilbronn, and since 1967 it has served as a sports boat harbor. The old lock is still operational and the last hand-operated lock on the Neckar, but since the construction of the Friedrich Ebert Bridge in 1993, the access height to the canal has been reduced to around 3.30 meters. On the Kraneninsel, which forms the right bank of the Wilhelm Canal, all the factory buildings still located there were blown up in 1959, with the exception of the Hagenbucher . Since then, the right bank has been designed as a green area that is crossed by Kranenstrasse. In 1962 and again more recently, the gates of the old lock were renewed.

Individual evidence

- ↑ Lauer was a term used in the Rhine-Neckar area for a “ship landing stage, stacking place and market f. best. Merchandise". German legal dictionary . Verlag Hermann Böhlaus Successor, Weimar 1984–1991, Volume VIII, Column 758–759

- ↑ Heilbronn - planning the reconstruction of the Altatdt, Heilbronn City Archives, Heilbronn 1994, p. 73

- ↑ Alexander Renz: Chronicle of the city of Heilbronn . Volume VII: 1952-1957. Heilbronn City Archives, Heilbronn 1996, ISBN 3-928990-60-8 , p. 55 ( Publications of the Archives of the City of Heilbronn . Volume 35).

- ↑ a b Alexander Renz: Chronicle of the city of Heilbronn. Volume VII: 1952-1957 . Heilbronn City Archives, Heilbronn 1996, ISBN 3-928990-60-8 ( Publications of the Heilbronn City Archives . Volume 35). P. 337

- ^ Julius Fekete, Simon Haag, Adelheid Hanke, Daniela Naumann: Monument topography Baden-Württemberg . Volume I.5: Heilbronn district. Theiss, Stuttgart 2007, ISBN 978-3-8062-1988-3 , pp. 112 .

- ↑ Alexander Renz: Chronicle of the city of Heilbronn. Volume VII: 1952-1957 . Heilbronn City Archives, Heilbronn 1996, ISBN 3-928990-60-8 ( Publications of the Heilbronn City Archives . Volume 35). P. 422

- ↑ a b Chronicle of the WMBC 1952–2013

literature

- Fritz Bürkle : Karl August Friedrich von Duttenhofer (1758–1836). Pioneer of hydraulic engineering in Württemberg . Klett-Cotta, Stuttgart 1988, ISBN 3-608-91521-4 ( Publications of the Stuttgart City Archives . Volume 41)

- Willi Zimmermann: Heilbronn and its Neckar in the course of history . In: Historischer Verein Heilbronn, 21st publication , Heilbronn 1954

- Willi Zimmermann: Heilbronn. The Neckar: the city's fateful river . Heilbronner Voice, Heilbronn 1985, ISBN 3-921923-02-6 (series on Heilbronn. Book 10).

Web links

Coordinates: 49 ° 8 ′ 41 ″ N , 9 ° 12 ′ 48 ″ E