Chain shipping

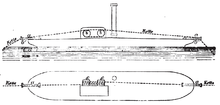

The chain shipping (often with the preamble Tauerei called) was a form of towage and was applied in the second half of the 19th and in the first half of the 20th century in several European rivers. It revolutionized shipping on rivers insofar as a single chain tugboat powered by a steam engine could pull many unpowered barges - so-called barges - inexpensively. The chain was pulled over the ship by chain drums mounted amidships on the deck and driven by the steam engine, with the chain being lifted out of the water via the forecastle, running over the deck of the steamer and sinking back into the river behind. The chain lay continuously in the middle of the river, following the bends of the river. Many of the rivers that were not straightened at the time were characterized by strong currents and shallow depths, for which paddle steamers were less suitable.

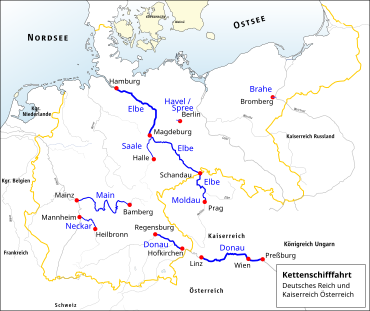

Chain shipping began on the Seine in France and on the Elbe in Germany, but it also took place on other rivers such as the Neckar , Main and Saale . Initially, the chain ships also drove down the chain. Because of the time-consuming and complicated crossing maneuvers between ships traveling uphill and downhill, the chain tugs were soon equipped with an additional auxiliary drive so that they could travel downhill independently of the chain.

historical development

Technical preliminary stages before the 19th century

In the days before chain shipping, the transport of goods on the river was limited to wooden ships without their own propulsion. The boats were allowed to drift downstream or the wind power was used with sails. Upstream people and / or animals pulled the boats on long ropes from the bank, which is known as towing . In shallow waters, the boats could also be moved upstream by pinning (pushing the boat from the river bottom with the help of long poles). Where a towing from the bank was not possible, a form of locomotion was practiced which is known as " warping ". These stretches of river could be overcome by anchoring a rope above the point in question, on which the crew pulled themselves upstream on their boat.

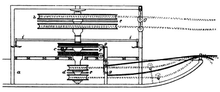

The Italian engineer Jacopo Mariano showed an illustration in an illuminated manuscript from 1438 with the basic idea of the later chain shipping. The ship pulls itself upstream on a rope laid lengthways in the river. The rope is wrapped around a central shaft that is driven by two lateral water wheels (see figure above). Behind the ship there is a small ship-like body that is caught by the current, keeps the rope taut and thus ensures the necessary friction on the shaft.

Around 1595, Fausto Veranzio described a system of cable navigation that allowed a higher speed and also managed without an additional drive engine. Two boats are connected with a rope that is guided over a pulley that is firmly anchored in the river. The smaller boat traveling downstream is driven more strongly by the water due to the large water sails attached to both sides and thus pulls the larger boat uphill against the current. The large cargo ship in the picture has two water wheels on the side, which also wind up the rope and thus increase the speed. However, it is not known to what extent the system was used in practice.

In 1723, Paul Jacob Marperger , who later became the Electorate of Saxony, described a proposal by the mathematics professor Nicolaus Molwitz from Magdeburg to use a mechanical aid to overcome the rapid waterfall under the Magdeburg bridges. Until then, 50 men would have been necessary to overcome this section of the river. The idea was to build a “machine” with two horizontal shafts, whereby the ropes should be folded around the front shaft in such a way that they repeatedly unwind from the front shaft and wind onto the rear shaft. With the additional use of levers, according to Marperger, it should be possible to get by with five or six men for the ship passage. At the same time, however, he emphasizes that the machine was “specified” , but never “came into use” . Based on the description, parts of this basic principle appear to be similar to the structure of later chain ships. This section of the river was later the starting point for the first chain ships in Germany.

The first practical attempts with a rope ship were made in 1732 at the instigation of Marshal Moritz von Sachsen, who was in French service . These took place on the Rhine near Strasbourg . For this purpose, three pairs of drums with different diameters were arranged on a rotatable vertical axis driven by two horses. Depending on the force required, the rope was moved by wrapping one of the drum pairs, while the other two drum pairs ran freely. This variable gear ratio enabled better use of the power. Compared to towing from land, the load moved forward doubled with the same number of horses used.

Attempts in the first half of the 19th century

From 1820 there were several inventors in France who deal with the technical implementation of the propulsion of ships with ropes or chains. This also included the engineers Tourasse and Courteaut with their experiments on the Saône near Lyon. They attached an approximately 1 km long hemp rope to the bank. This was wound up on a drum on the ship and pulled the ship forward. Six horses moved the drum.

With the advancing industrialization in the 19th century, the need for transport capacities on the waterways increased significantly. However, industrialization also revolutionized transport itself. With the steam engine , the first motor for an independent propulsion of ships was available. However, the performance of the first steam engines was still relatively low, while their weight was also very high. So they looked for ways to convert the force as effectively as possible into movement of the ship.

A little later, the two engineers Tourasse and Courteaut carried out tests using steam power on the Rhone between Givors and Lyon . An escort ship powered by steam transported the 1000 meter long hemp rope upstream and anchored it here on land. Then the escort ship drove back and brought the lower free end of the rope to the actual rope. He pulled himself up the river on the rope and in doing so gave the rope back to the drum of the escort ship during the pull. During this procedure, a second escort vessel took off and hurried upstream to anchor a second rope and thus save waiting time.

Vinochon de Quémont replaced the rope with a chain during experiments on the Seine. The results of the first attempts can be read in the yearbook of inventions from 1866: How not a continuous chain was used in all of these [previous] attempts, but the pull chain had to be moved a little forward again and again by a boat before that The results appeared so satisfactory that as early as 1825, under the direction of Edouard de Rigny, a company for sailing the Seine on the Rouen-Paris route was formed according to this system. However, the introduction of the “entreprise de remorquage” failed due to faulty construction. The chain steamer "La Dauphine" was not built exactly according to Tourasse's specifications. The draft of the ship was too great and the engine too weak. Also, the winches were too far back on the deck. But the company's financial strength was also too low.

In 1826 MF Bourdon tried out a variant with two steam trains. One of the ships drove ahead, driven by a paddle wheel, and at the same time unwound a rope with a length of 600 m. After unwinding, it was anchored and pulled the second pulling ship with the attached barges up to it, the rear pulling ship supporting the process by its own drive. Then the two towers exchanged positions and the same procedure ran again. However, a lot of time was lost due to the anchor maneuvers.

Since these attempts in the first half of the 19th century, chain navigation technology has improved steadily and was successfully used for the first time on the Seine in France. Other French rivers and canals were then also provided with the chain. In Germany the chain had been relocated to the Elbe, Neckar, Main, Spree, Havel, Warthe and Danube, and chain shipping was also widespread in Russia. A total of around 3,300 kilometers of chain had been laid in Europe.

Changes due to chain shipping in the second half of the 19th century

Chain shipping revolutionized inland shipping, especially on rivers with stronger currents. Compared to the towage shipping that was common up until then, a chain steamer could pull significantly more and significantly larger barges. The possible payload of a single barge increased fivefold in just a few years. In addition, the chain transport was much faster and cheaper. For example, the number of possible journeys a ship can take on the Elbe has almost tripled. Instead of two trips, the skippers could make six to eight trips a year or cover up to 8,000 kilometers a year instead of 2,500 kilometers. The delivery times were shortened accordingly and adhered to more reliably while at the same time falling costs.

It was only through the use of the steam engine that it was possible to meet the increasing demand for transport capacities of increasing industrialization in the second half of the 19th and first half of the 20th century. Chain shipping also offered the skippers with their barges the opportunity to assert themselves against the increasing competition from the railways. Before the introduction of chain shipping, paddle steamers were already active as tugs and cargo ships on some sections of the river, but they did not lead to a breakthrough in mass transport. The paddle steamers could not guarantee regular transport due to their dependence on the water level of the river. Only regular timetables with fast connections, as well as guaranteed, low transport fees for chain shipping made tug shipping competitive.

With the development and spread of new propulsion systems such as screw drives and diesel engines in the first half of the 20th century, self-propelled ships became more and more popular. The expansion of the river systems (canalization and lock construction), as well as the competition on road and rail, further reduced the profitability of chain shipping, which is designed for continuous towing. Chain tugs were only used occasionally on particularly difficult sections of the river.

Distribution in Europe

France

In 1839 the first technically and economically successful chain steamer "Hercule" was built and used on an approximately 5 to 6 kilometer long, current-rich section of the Seine within the urban area of Paris. Edouard de Rigny had failed on this section of the river a few years earlier due to technical difficulties.

Starting from Paris, chain shipping spread from 1854 to the upstream city of Montereau at the mouth of the Yonne , and downstream to Conflans (at the confluence of the Oise ). From 1860 it was expanded towards the mouth of the Seine even as far as Le Trait . The maximum total length of the chain in the Seine was 407 kilometers. In addition, from 1873 there was a 93-kilometer stretch on the Yonne itself (between Montereau and Auxerre ).

The nature of the river bed of the Seine offered optimal conditions for chain shipping. The river was evenly deep, had a relatively steep gradient and its bed was sandy and regular. In contrast, the rivers whose source is in the Alpine region were less suitable. These carried large amounts of sand with them, especially during strong floods . The chain was repeatedly buried on long stretches of sand and rubble during attempts at chain shipping on the Rhone . The attempts on the Saône also failed and were stopped relatively quickly.

In addition to rivers, chain shipping in France was also used to transport ships on canals. The tunnels in the area of the apex support were very long and electrically powered chain tugs hauled the ships here. Due to the insufficient ventilation of the tunnel system, some of the electrically operated chain tugs are still in operation even after the introduction of self-propelled motor ships.

Belgium

In Belgium , chain steamers operated on the Canal de Willebroek between Brussels and the confluence with the Rupel from 1866 . In contrast to the chain tugs in France and Germany, a system from Bouquié was used with the chain tugs in Belgium, in which the chain was not guided over the center line of the ship, but only over a chain pulley on the side of the ship. The chain pulley was set with teeth to prevent the chain from sliding. About five tug trains ran each day in both directions, with each train containing 6 to 12 ships. Each stance has its own chain ship, so that the chain at the locks broken and each end of the chain is attached to the lock on a main Anbindepfahl.

German Empire and Austrian Empire

Elbe and Saale

In Germany, chain shipping began in 1866 with the laying of an iron chain on the Elbe . The first regular towing service with a chain steamer was carried out on a section of the Elbe between Magdeburg -Neustadt and Buckau . The length of this route was about three quarters of the Prussian mile (a good 7.5 km - route length thus 5 to 6 km). There the Elbe has a particularly high flow speed due to the cathedral rock . The Hamburg-Magdeburger Dampfschifffahrtsgesellschaft operated the chain steamers there.

The first two steamships on the Elbe were 6.7 meters wide and 51.3 meters long with about 45 kW (60 hp) and pulled four barges up to 250 tons. In 1871 the chain was already from Magdeburg to Schandau on the Bohemian border. Three years later, the Hamburg-Magdeburg steamship company expanded the route in a north-west direction to Hamburg . Up to 28 chain tugs rattled up the Elbe over a total length of 668 kilometers. In 1926/27, chain shipping was discontinued in large sections of the Elbe and the chains were lifted. The chain steamers were only used in particularly difficult sections of the route. The last section in Bohemia was discontinued in 1948.

On the Saale , the line from the mouth of the Saale to Calbe was put into operation in 1873 and extended to Halle (105 km chain) by 1903 . The last chain ship on the Saale ran in 1921.

Danube

After the concession to practice chain shipping was granted in 1869, the chain was moved by the Danube Steamship Company from Vienna about 65 km down to Pressburg (German name for Bratislava ). In 1871, however, chain shipping was already banned on some sections of the route. From 1881, chain ships also drove on the Danube from Spitz about 110 km up to Linz . Ten chain boats were in use. Chains breaking more and more often (on average once per trip) were the reason for the conversion of the chain ships into pulling ships in 1890. In 1891 the chain shipping company was established between Regensburg and Hofkirchen (113 km). In 1896 chain shipping between Vienna and Ybbs was discontinued , and in 1906 chain shipping between Regensburg and Hofkirchen was discontinued.

Due to the strong current on the Danube, the chain boats could not go down the valley on the chain. They therefore had large side paddle wheels with 300–400 hp as an additional drive.

Brahe

The 15 km long lower Brahe (Brda in Polish) served as a connection between the Vistula and the well-developed network of waterways with Western Europe. This waterway was particularly important for the transport of wood, but the raft wood had to be dragged upstream on the Brahe between the confluence with the Vistula and the Bydgoszcz town lock. For this purpose, horses were used for a long time on the 26 meter wide, curvaceous and relatively fast flowing section of the river. On November 12, 1868, the owners of the Bydgoszcz driver's office, which was responsible for towing, applied for a license to introduce a chain-towing operation on the lower Brahe to the government in Bydgoszcz.

According to the application, the license of June 3, 1869 was limited to 25 years and essentially corresponded to the Prussian regulations applicable to the Elbe. Immediately afterwards, in the summer of 1869, the first test drives began with a chain steamer built by the Buckau machine factory. However, operations had to be stopped again in the autumn because the tractor could not provide the required performance and speed. A replacement tug with sufficient power could be used from the summer of 1870. Nevertheless, only one or two trips could be made per day. It was only with the construction of a breakthrough on the most critical section of the route in March 1871 and the procurement of a second chain steamer in spring 1872 that a significant proportion of the rafts could be transported by the chain tugs.

One of the steamer put the rafts together in the area of the Braem estuary and towed them about a kilometer up the river. Here he handed the rafts about 100 meters long and 7.5 meters wide to the second steamer, which managed the remaining 14 kilometers to the Bydgoszcz town lock. Transportation was profitable and the number of chain steamers was increased to four. On April 30, 1894, the Minister of Commerce and Industry and the Minister of Public Works extended the concession for another 25 years.

Neckar

As early as 1878, the first chain tug with nine barges attached was also on the Neckar between Mannheim and Heilbronn . The operation of the chain shipping was subject to the chain shipping on the Neckar AG . When the regulation of the river through barrages began in the 1930s and the expansion into a large waterway began, this meant the end of the Neckar chain-towing trade, which was still profitable up to that point, and its replacement by large inland vessels.

Havel and Spree

There were also brief attempts at chain shipping on the Havel. Although the current of the Havel has always been low, a large number of loaded barges could be towed inexpensively with one chain steamer. On the Havel and the Spree between Pichelsdorf near the then city of Spandau and the Kronprinzenbrücke , the substructure on the edge of what was then Berlin, the Berliner Kran-Gesellschaft , founded in 1879 by two Englishmen, started a chain shipping on June 16, 1882. In Havelland there were numerous brickworks whose products were almost exclusively transported by ship. In the summer of 1894, chain shipping on the Havel and Spree was discontinued. The development of the propeller-driven tugboat had displaced chain shipping.

Main

Chain shipping also existed on the Main from 1886 to 1936. The chain lay in the 396-kilometer-long navigable river between Mainz and Bamberg . Up to 8 chain tugs were in use on the Main. The chain was removed from the Main after 1938 and recycled. The chain ships on the Main were also called Maakuh, Määkuh or Meekuh.

Russia

The "Volga-Tver'sche Kettenschifffahrtsgesellschaft" set up a towing operation on the upper Volga between Rybinsk and Tver from 1871 . The approximately 375 km long section of the river was poorly regulated and often had a water depth of only 0.52 m. The dividend achieved was only small. In 1885, 10 chain steamers with an output of 40 or 60 hp were in use on the Volga.

Chain shipping on the Scheksna was also established in 1871 and operated by the " Chain Steamship Company on the Scheksna" based in St. Petersburg . The chain extended over a length of 445 km from the confluence with the Volga to St. Petersburg. In the beginning, the chain towing operation achieved poor results. As a result, the company stopped chain shipping on an approximately 278 km long stretch with a very slight gradient and replaced it with a tugboat operation. On the 167 km remaining stretch with strong currents, chain shipping yielded a dividend of around 30% in some years. In 1885, the company operated 14 chain steamers with an output of 40 hp each on this section of the river.

In addition, chain shipping was on the Moskva with 4 steamers with 60 HP each and on the River Swir with 17 steamers with a total of 682 HP.

technical description

Chain tow ship

The chain was lifted out of the water at the bow of the ship via an extension (boom) and led across the deck along the ship's axis to the chain drive in the middle of the ship. The power transmission from the steam engine to the chain usually took place via a drum winch . From there the chain led over the deck to the boom at the stern and back into the river. The lateral mobility of the boom and the two rudders attached to the front and rear made it possible to put the chain back in the middle of the river even when the river bends.

Chain

The chain had to be financed by the chain shipping companies themselves and was designed as a seamless round steel chain. The individual chain links consisted of an easily weldable round bar with a low carbon content. The round bars were typically 18 to 27 millimeters thick, depending on the section of the river. Nevertheless, there were always chain fractions. At a distance of a few hundred meters there were shackles as chain locks that could be opened by unscrewing the bolt when two chain tugs met. Most of these high quality necklaces were made in England or France.

Encounter between chain boats going uphill and downhill

If two chain vessels met, a complicated evasive maneuver was necessary in which the chain was passed on to the other tug via an auxiliary chain. This maneuver meant a delay of at least 20 minutes for the towing formation going uphill, while the downhill vessel suffered a loss of time of around 45 minutes as a result of the maneuver. With the introduction of additional drives, the chain tug went downhill outside the chain, and evasive maneuvers were no longer necessary.

Try with an endless chain

To avoid the high cost of purchasing a chain or a cable, Dupuy de Lome on the Rhône carried out experiments with an endless chain. The tractor brought its own chain. The chain was let into the water at the fore ship (bow) and lay on the river bed under its own weight. At the rear of the ship (stern), the chain was pulled up out of the water and transported forward over the deck of the ship by the chain drive. Provided that the lower part of the heavy, self-contained chain is prevented from sliding through the riverbed, the ship pulls itself forward. However, this type of drive was not used economically, since a reasonable power transmission is only given with an adapted chain length. If the water depth is too great, the length of the chain section that comes to rest on the river bed and thus the required friction is reduced. If the water depth is too shallow, the chain would be too long and would not be stretched, but would come to lie on the bottom in clumps. A variation in the river depth therefore makes it difficult to steer the ship.

Concessions

In order to be able to operate the chain shipping, the company responsible for the chain towing operation needed a license. The concession guaranteed the companies the sole right for this type of ship transport. Since the purchase of the chain and the chain tractor represented a high financial burden for the operator, the concession offered a certain degree of security. The competition from the railroad, wheeled tractors or the tow train persisted. In return, the rights and obligations towards the boatmen were regulated in the concession. All boats had to be carried at state-set tariffs.

Comparison of a chain tugboat and a paddle steamer

Chain shipping not only had to compete with the railways, but also felt the competition on the waterways. Compared to paddle steamers , the chain steamers had advantages wherever there were difficulties for shipping, such as rapids, sharp bends in the course of the river and shallows.

Flow and flow velocity

In a wheel or screw steamer, the water is pushed backwards to generate the propulsion. A not inconsiderable part of the energy is converted into water turbulence and is therefore not available for propelling the ship. The chain steamer, on the other hand, pulls itself forward on the fixed chain and can thus convert a much larger proportion of its steam power into propulsion. With the same tractive effort, coal consumption is around two thirds lower.

At higher flow speeds of the river, the advantage shifts more and more in favor of the chain steamers. Ewald Bellingrath set the following general rule in 1892: If the river has an average gradient of up to 0.25 ‰ , paddle steamers are superior. Between 0.25 and 0.3 ‰ gradients, both types of towing are said to be equivalent. Chain steamers are more advantageous to use above 0.3 ‰. From a gradient of 0.4 ‰ paddle steamers would have increasing difficulties and would have to do without towing at a gradient of 0.5 ‰.

Practical experience has shown that free-moving wheeled tractors with 400 HP (about 300 kW) at a flow speed of 0.5 meters per second (1.8 km / h) have a speed of about 3 meters per second (10.8 km / h) / h). As a result, they could tow economically up to a current of 2 meters per second (7.3 km / h). Larger falls could also be overcome if they were only a short distance. By slacking off the tow ropes, the wheeled tractor was able to overcome the obstacle. When the attachment from cargo ships came into this area, the paddle steamer had already overcome the area with higher currents and was able to use its full traction again. At a current speed of over 3 meters per second, the useful power would decrease to zero. Many of the falls were relatively short and the maneuver described could also be overcome by wheeled tractors.

Too strong a current during high water could also be problematic for chain shipping. Depending on the design of the river bed, strong debris movements led to ballasting and thus to the chain being covered with rubble and stones. A cliff-rich river bed or sections of the Danube containing large boulders also led to the chain becoming obstructed.

The water churned up by the paddle steamers also caused significantly stronger wave movements. The waves could increasingly lead to bank damage. The additional currents and waves also created additional resistance for the towed cargo ships. Behind a chain tractor, however, the annex was in calm waters.

Water depth

Some chain tugs are designed with a shallow draft of only 40–50 centimeters for use at very low water levels and are thus adapted to the conditions of many rivers of that time. Even with a water depth of 57 centimeters, efficient operation on the Neckar was still possible. Paddle steamers, on the other hand, require significantly greater water depths of 70 to 75 centimeters for economic use. With strong currents, the minimum water depth for paddle steamers increases. Screw tugs also need a great deal of water to work effectively. Only a screw that is located deep in the water can generate sufficient propulsion.

Chain ships not only have a shallow draft, their technical principle is also advantageous for shallow water depths: When the water depth is shallow, the chain rises flat out of the water and a very high proportion of the steam power can be converted into propulsion. However, if the water depth is very deep, the amount of energy required to lift the accruing chain increases. Due to its own weight, the tensile force is directed downwards at an angle and efficiency drops. In addition, the maneuverability decreases with increasing depth.

Investment costs

The chain itself meant high investment costs for society. On the approximately 200-kilometer section of the Main between Aschaffenburg and Kitzingen, the estimate for the first chain, including the laying, was over one million marks. This corresponded almost exactly to the total price for eight chain tractors that were to be used on this section. The chain was subject to constant maintenance and had to be replaced approximately every 5 to 10 years.

In addition to the costs for the chain, there were also costs for converting ferries , which cost around 300,000 marks on this route. This conversion was necessary because the chain of the chain ships and the ropes of the ferries were not allowed to cross. Instead of the cable ferries that had been customary up to that time, they had to switch to yaw ferries .

flexibility

The first chain ships were tied to the chain in their movement, that is, they made both the ascent and the descent on the chain. During an encounter there were evasive maneuvers with a high loss of time. On the 130-kilometer Neckar, with a total of seven chain tractors, that means a loss of at least five hours for the descent with six encounters. In order to avoid the maneuver, the barges were transferred from one chain steamboat to the other on some sections of the river in France. Such a handover was also associated with a considerable loss of time.

The towing operation with barges usually only took place on the ascent. The barges were mostly drifted down the valley to save money. In strong currents, operating a long tow would have been dangerous. If the chain tug was forced to suddenly stop (for example due to a broken chain), there was a high risk that ships in the rear would run into the ships in front, leading to an accident .

At least in the early days of chain shipping, paddle steamers were slower on the mountain journey than chain ships. On the other hand, they were faster on the descent and could also take barges with them.

In addition to the technical restrictions, the chain-towing companies were given rules through concessions , which for example stipulated the order of transport and the transport fees. As a result, they could not react as flexibly to supply and demand as the companies with wheeled tractors.

The end of chain shipping

One reason for the end of chain shipping was the increase in the technical performance of the new wheeled tow steamers. They had an increased pulling power with reduced coal consumption. The composite steam engines on the paddle steamers used only about half of the coal in relation to the output. Such composite steam engines could not be used on chain steamers because of the jerky tightening. At the same time, the chain shipping companies were burdened by high installation and repair costs.

Another reason for the end was restructuring of the river courses. Many current regulations were made on the Elbe, with the gradients becoming more and more balanced and the curvatures of the river and the shallows diminishing. This also reduced the advantages of chain shipping.

At the Main and the Neckar, numerous barrages and locks were added as artificial obstacles for the chain tugs. The damming of the river led to greater water depth and at the same time reduced the flow velocity. Above all, the long tow trains at the locks of the barrages had to be split up and locked separately, which led to considerable time losses.

Chain shipping in literature

A humorous historical documentary comes from the American writer Mark Twain , who in his travelogue Stroll through Europe (1880) describes the chain shipping on the Neckar as follows:

“We ran forward to see the vehicle. It was a steamer - because in May a steamer had started running up the Neckar. It was a tugboat, and one of a very strange shape and appearance. I had often watched it from the hotel and wondered how it was being propelled, because apparently it had no screws or blades. Now it came frothed up, making a lot of noise of various kinds, and occasionally increasing it by making a hoarse whistle sound. He had hung nine boats at the back, which followed him in a long, narrow row. We met him in a narrow place between embankments, and there was hardly room for the two of us in the narrow passage. As he drove by, puffing and moaning, we discovered the secret of his drive. He didn't go upriver with paddles or propellers, he pushed himself up by pulling himself forward on a large chain. This chain is laid in the river bed and only attached at the two ends. It's seventy miles long. It enters through the bow of the ship, rotates around a drum and is unplugged aft. The steamer pulls on this chain and drags itself up or down the river. Strictly speaking, it has neither a bow nor a stern, because it has a rudder with a long blade at each end and it never turns. He constantly uses both oars, and they are so strong that, despite the strong resistance of the chain, he can turn right or left and steer around bends. I would not have believed that this impossible thing could be done; but I've seen it done, so I know that there is an impossible thing that can be done. "

literature

- Rope. In: Meyers Konversations-Lexikon. Volume 15, 1888, p. 15.543.

- Prospect for chain tug shipping on the Upper Elbe from Magdeburg to Schandau. Blochmann, Dresden 1869. (digitized version)

- Ewald Bellingrath : A life for shipping. In: Sigbert Zesewitz, Helmut Düntzsch, Theodor Grötschel: Writings of the Association for the Promotion of the Lauenburger Elbschiffahrtsmuseum e. V. Volume 4, Lauenburg 2003.

- Georg Schanz: Studies on the bay. Waterways. Volume 1: The chain towing on the Main. CC Buchner Verlag, Bamberg 1893. (digitized version)

- Sigbert Zesewitz, Helmut Düntzsch, Theodor Grötschel: Chain shipping. VEB Verlag Technik, Berlin 1987, ISBN 3-341-00282-0 .

Web links

- Chain towing from Lueger, Lexicon of all technology 1907.

- Chain Shipping in France (1865) on Wikisource

Individual evidence

- ↑ a b c d e f Sigbert Zesewitz, Helmut Düntzsch, Theodor Grötschel: Kettenschiffahrt . VEB Verlag Technik, Berlin 1987, ISBN 3-341-00282-0 , chap. 1 , p. 9-15 .

- ^ A b c Franz M. Feldhaus: The technology of prehistoric times, the historical time and the primitive peoples, a manual for archaeologists and historians, museums and collectors, art dealers and antiquarians. Engelmann, Leipzig / Berlin 1914, pp. 942–944 ( digitized text (PDF; 2.7 MB))

- ^ A b Franz Maria Feldhaus: Fame sheets of technology from the original inventions to the present. Verlag F. Brandstetter, Leipzig 1910, pp. 399-401. ( Text archive - Internet Archive )

- ↑ Sigbert Zesewitz, Helmut Düntzsch, Theodor Grötschel: chain shipping . VEB Verlag Technik, Berlin 1987, ISBN 3-341-00282-0 , chap. 1 , p. 9 . Quote from Paul Jacob Marpenger: “We cannot help but use the machine, which the famous Mechanico and Math. Prof. Nicolaus Molwitz of Magdeburg had given, but which was used by the heavily laden ships coming up the Elbe Approximately 5th to 6th man, since both 50th are necessary at the time, should have been pulled up over the rapid waterfall under the Magdeburg bridges, one more time to remember, but such a machine consists in 2 lying waves, whereupon the ropes or funes Tractorii, namely by means of six exchangeable Vecitium-Homorodromorum, or levers rising straight away, with this circumstance that the ropes, as they are folded around the front shaft, repeatedly come off the same, and onf the rear one, which winds up The whole machine can be attached to a pontoon or a boat. "

- ↑ a b c d e Cpt. CV Suppán: waterways and inland waterways. Verlag A. Troschel, Berlin, 1902, pp. 261-270, ( Textarchiv - Internet Archive ).

- ↑ a b c d rope . In: Meyer's large conversation lexicon . A reference book of general knowledge. 4th edition. tape 15 . Verlag des Bibliographisches Institut, Leipzig / Vienna 1888, p. 543-544 ( peter-hug.ch [accessed November 14, 2009]).

- ↑ Steam wagons and steam ships. In: H. Hirzel, H. Gretschel: Yearbook of inventions and advances in the fields of physics and chemistry, technology and mechanics, astronomy and meteorology . Quandt & Handel publisher, Leipzig 1866, p. 178–183 ( digitized text in the Google book search).

- ^ A b c d Gustav Carl Julius Berring: The rigging shipping on the Seine. In: Centralblatt der Bauverwaltung. Berlin 1881, pp. 189-191.

- ↑ a b Peter Haas: About rope and chain shipping. (PDF; 5.9 MB) Schifferverein Beuel, archived from the original on September 23, 2012 ; Retrieved on January 17, 2016 (Source: Willi Zimmerman: Contributions to Rheinkunde. Rheinmuseum Koblenz, 1979).

- ↑ a b c d Erich Pleißner: Concentration of freight shipping on the Elbe. In: Journal for the entire political science. Verlag der H. Lauppschen Buchhandlung, Tübingen 1914, Supplement L, pp. 92–113, Textarchiv - Internet Archive

- ↑ a b c d e f g Hermann Schwabe: The development of German inland shipping up to the end of the 19th century . (PDF; 826 kB). In: German-Austrian-Hungarian Association for Inland Shipping, Association publications. No 44, Siemenroth & Troschel, Berlin 1899, pp. 57-58.

- ↑ Chain shipping on the Saxon Elbe. , In: Austria, Archives for Consular Affairs, Economic Legislation and Statistics. Year XXII, No. 34, Kaiserl.-Königl. Hof- und Staatsdruckerei, Vienna 1870, pp. 638–639.

- ↑ a b c J. Fölsche: Chain shipping on the Elbe and on the Seine. In: Deutsche Bauzeitung. 1, 1867, pp. 306-307 and pp. 314-316.

- ↑ Tourasse, François-Noël Mellet: Essai sur les bateaux à vapeur appliqués à la navigation intérieure et maritime de l'Europe , p. 180, on Google Books

- ↑ Le toueur de Riqueval fête son centième anniversaire. In: Fluvial magazine. June 15, 2010, accessed October 31, 2010 (French).

- ↑ Karl Pestalozzi: International Congress for Inland Navigation in Brussels. In: Schweizerische Bauzeitung. Volume 5/6, Verlag A. Waldner, Zurich 1885, p. 67.

- ^ R. Ziebarth: About chain and rope shipping with regard to the experiments at Liège in June 1869. In: Association of German Engineers (ed.): Journal of the Association of German Engineers. Volume XIII, Issue 12, Rudolph Gaertner, Berlin 1869, pp. 737-748, panels XXV and XXVI.

- ^ The ship train on Belgian waterways. In: Alfred Weber Ritter von Ebenhof: Construction, operation and administration of the natural and artificial waterways at the international inland navigation congresses in the years 1885 to 1894. Publishing house of the KK Ministry of the Interior, Vienna 1895, p. 120 ff. Text archive - Internet Archive .

- ↑ The Inland Navigation Congress in Brussels. In: Journal of the Association of German Engineers. Volume XXIX, self-published by the association, Berlin 1885, pp. 473–474.

- ↑ Rolf Schönknecht, Armin Gewiese: On rivers and canals - The inland navigation of the world. Verlag für Verkehrwesen, 1988, ISBN 3-344-00102-7 , p. 56.

- ↑ The chain - a chapter in shipping on the Saale. Preisnitzhaus e. V., accessed on December 18, 2009 (information brochure on the traveling exhibition).

- ^ History of the DDSG up to 1900. (No longer available online.) DDSG Blue Danube Schiffahrt GmbH, archived from the original on October 19, 2012 ; Retrieved December 10, 2009 .

- ↑ W. Krisper: History of the Danube shipping and 1.DDSG. (No longer available online.) Archived from the original on August 3, 2008 ; Retrieved December 10, 2009 . Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice.

- ↑ a b c Sigbert Zesewitz, Helmut Düntzsch, Theodor Grötschel: Kettenschiffahrt . VEB Verlag Technik, Berlin 1987, ISBN 3-341-00282-0 , chap. 1 , p. 130-133 .

- ↑ Kurt Groggert: Personenschiffahrt on Havel and Spree Berliner contributions to the history of technology and industrial culture, Volume 10, Nicolaische Verlagsbuchhandlung Berlin, 1988, ISBN 3-7759-0153-1 , S. 102nd

- ↑ Karola Paepke, Hans-Joachim Rook (ed.): Sailors and steamers on the Havel and Spree . Brandenburgisches Verlagshaus, Berlin 1993, ISBN 3-89488-032-5 , p. 46.

- ↑ Wolfgang Kirsten: The "Maakuh" - chain shipping on the Main. (PDF; 4.9 MB) In: FITG Journal No. 1-2007. Förderkreis Industrie- und Technikgeschichte e. V., April 2007, pp. 13-20 , accessed on September 20, 2012 .

- ↑ Otto Berninger: The chain shipping on the Main. In: Mainschiffahrtsnachrichten of the Association for the Promotion of the Shipping and Shipbuilding Museum Wörth am Main. Bulletin No. 6 April 1987.

- ↑ a b c d e II a. Steam navigation on the Russian waterways. In: Friedrich Matthaei: The economic resources of Russia and their significance for the present and the future. Second volume, Verlaghandlung Wilhelm Baensch, Dresden 1885, p. 370.

- ↑ a b c J. Schlichting: Chain and rope shipping. In: Deutsche Bauzeitung. Volume 16, No. 38, Berlin 1882, pp. 222-225 and No. 39, pp. 227–229 (also BTU Cottbus: H. 35-43 = pp. 203–254. )

- ↑ a b Dew works on Russian rivers . In: Deutsche Bauzeitung. Volume 15, No. 89, Berlin 1881, p. 492, (also BTU Cottbus: H. 88-96 = p. 489-540. )

- ↑ Anton Beyer: Notes about the ship pull by means of sunk chains or wire ropes and about the experiments made with the rope remorqueurs on the Maas in Belgium . In: Johannes Ziegler (Ed.): The archive for marine systems: communications from the fields of nautical science, shipbuilding and mechanical engineering, artillery, hydraulic engineering, etc. Volume 5, Carl Gerold's Sohn, Vienna 1869, pp. 466–481. ( Digitized in the Google book search)

- ↑ Sigbert Zesewitz, Helmut Düntzsch, Theodor Grötschel: chain shipping . VEB Verlag Technik, Berlin 1987, ISBN 3-341-00282-0 , 4.6, p. 180-183 .

- ↑ Carl Victor Suppan: waterways and inland navigation. A. Troschel, Berlin-Grunewald 1902, section: Inland navigation. ( Steam navigation. Chapter: Tensile tests using an endless chain. Pp. 269–270 Textarchiv - Internet Archive ).

- ↑ a b c d e f g h i Georg Schanz: Studies on the bay. Waterways. Volume 1: The chain towing on the Main. CC Buchner Verlag, Bamberg 1893, pp. 1-7. ( digitized form ) from Digitalis, Library for Economic and Social History Cologne, accessed on October 29, 2009.

- ↑ The train of ships on the waterways. The fifth international inland shipping congress in Paris in 1892. In: Alfred Weber Ritter von Ebenhof: Construction, operation and management of the natural and artificial waterways at the international inland navigation congresses in the years 1885 to 1894. Publishing house of the KK Ministry of the Interior, Vienna 1895, pp. 186–199, online: Construction, operation and management of natural and artificial waterways ... - Internet Archive

- ↑ Works in nine volumes, Volume 6, Stroll through Europe . German Ana Maria Brock. Carl Hanser-Verlag, 1977, Original: A Tramp Abroad, Part 3., Chapter XV, Charming Waterside Pictures, 1880 gutenberg.org ( Memento from April 25, 2007 in the Internet Archive )