Chain shipping in France

The chain shipping ( French Touage ) was one in France developed and in 1839 on the His -powered form of the inland waterway . From there, the technology spread to other rivers, especially to Germany. In this special type of ship transport, several barges were pulled by a chain tugboat along a chain laid in the river . Chain shipping ensured the survival of shipping after the emergence of competition from the railroad and was later displaced by wheeled and screw tugs and self-propelled ships.

Although the advantages of chain shipping were particularly evident in river sections with steeper slopes or shallow water, this type of ship pulling, unlike in other countries, also existed on canals . Chain tugs have been used with success on single-ship canal sections and especially in the very narrow ship tunnels. The later electrically operated chain tugs are still in use today in the area of canal tunnels.

Historical development of technology

Before the introduction of steam shipping, humans or animals dragged ships up the rivers with difficulty. This type of ship transport is called towing and for many centuries it was the only economic way of getting around in the inland navigation sector. The need for transport capacities increased during the industrialization of France . In addition, there has been an increasing need to increase the transport speed. Shipping competed directly with the railroad. The chain shipping allowed the boatmen to move their boats faster at consistently low costs. Regular timetables allowed for predictable delivery times.

The technical development of chain shipping started in France at the beginning of the 19th century. From 1820 onwards, several inventors worked on the principle in which a ship pulls itself along a rope or chain against the flow of the river. The technology of chain shipping made it possible to make optimal use of the steam engines' low power at that time . Chain tugs were superior to paddle steamers where the river had a high current. At the same time, a significantly shallower water depth was sufficient for them.

Chain shipping on the Seine

The condition of the river bed of the middle and upper reaches of the Seine from the confluence of the Yonne was particularly suitable for chain shipping. The river was evenly deep and had a relatively steep gradient. Despite its sandy bed , the Seine did not carry any easily movable debris . The course of the river changed little and the risk of silting up the chain was low.

The beginnings of chain shipping

In 1839 the first technically and economically successful chain steamer Hercule was built on behalf of the General Inspector of Shipping Latour du Moulin . This ran for the company Société pour établir le touage dans la traversée de Paris regularly on an approximately 5 to 6 kilometers long, current-rich section of the Seine within the urban area of Paris . Towing with horses was made more difficult in this section by the bank construction.

The new technology not only had supporters but also opponents. Many engineers wanted to solve the shipping problems by channeling the river. However, the chain laid in the river interfered with the construction of the locks required for this . In 1841 the Gesellschaft für Kettenschifffahrt applied for a concession with the purpose of abolishing towing with horses in favor of ships with steam on a chain. After extensive investigations, towing was banned in 1845 and chain shipping was expanded upstream to Port à l'Anglais near Vitry-près-Paris .

The revolution of 1848 ended the monopoly as the concession was in conflict with freedom of navigation and business. It was not until 1850 that a second chain steamer called Austerliz, designed by the engineer Dietz as early as 1846, significantly improved towing operations.

Expansion of chain shipping

A decree of Emperor Napoleon III. from 1854 allowed the company Eugène Godeaux and Sons as one of the first chain shipping companies to sink a chain for towing purposes in the Seine between the Paris locks at the Paris Mint and Pontoise . With three barges attached , the speed of the towing formation was 6 to 7 kilometers per hour. Because of his success, Eugène Godeaux had the idea of expanding chain shipping to areas outside Paris. He is considered the initiator for the spread of this type of ship transport in France.

In the same year, the imperial government granted him the license to found the Compagnie de Touage de la Basse-Seine et de l'Oise . This extended the route by the 72 kilometers long section of the lower Seine from Conflans (at the confluence of the Oise ) to the Port à l'Anglais near Paris and expanded the number of chain tugs to seven boats by 1857. These crawler tractors were built in Hull , England .

On the upper Seine, the Compagnie de touage de la haute Seine received the concession for chain shipping in 1856. This concerned the stretch from the lock de la Monnaie in Paris to the city of Montereau, 106 kilometers upstream, at the mouth of the Yonne . The expansion of this route took place gradually between 1856 and 1859. The seven chain tugs were built by Charles Dietz in Bordeaux and had an output of 16 to 35 hp . There is a detailed description of the last chain steamer called La Ville de Sans (1860).

After another concession was granted in 1860, the Compagnie de touage de Conflans à la mer expanded the chain from Conflans towards the mouth of the Seine. Until 1875 the chain was from Conflans to Le Trait (about halfway between Rouen and Le Havre ). The company operated the remainder of the route by means of paddle steamers from the start due to the low current and the sufficient water depth . In 1876 the chain below Rouen was removed from the river due to heavy silting.

Technical and economic details

At the time of the great expansion of chain shipping on the lower Seine (1856), the river was very irregular (shallow sections and those with steeper slopes alternated), the current often violent and the depth of the fairway decreased to less than, especially in the dry summer months 1.5 meters. Chain shipping, whose job it was to pull large tow trains cheaply under these adverse conditions for wheeled tractors, had rendered invaluable services during the period before the river canalization. It replaced the horse-drawn train that had been common up to that point, as well as numerous free-moving paddle steamers, and attracted almost all of the mountain traffic, so that its share was up to 97%. The valley traffic was largely carried out by mere drifting.

The train costs for a typical boat shape ( pinasse ) at that time were reduced from 0.03 francs to around 0.01 francs per kilometer and ton. In the first 36 years, the chain tugs pulled more than 1,800 million tonne kilometers from Conflans to Paris. The trade and industry of Paris thus saved about 30 million francs.

The wrought-iron chain that was used along the rivers in France was mostly 21 millimeters in diameter - measured on one of the two cylindrical parts of each chain link. In contrast to the usual anchor chains without a central bar, the individual chain links were designed as round steel chains . The chain had a mass of nine to ten kilograms per meter. The greater weight compared to a wire rope was, despite the higher acquisition costs, one of the main reasons for the decision against rope shipping . Another reason was that it was easier to repair in the event of a break. In the case of a chain, only the defective chain link had to be replaced, while the wire rope had to be spliced together.

The French chain tow steamers of the companies on the Seine (referred to in France as "toueur" and often also as "Tauer" in German literature) were made of iron , with the exception of the wooden deck . The typical length of the tugs was around 40 meters, while their width was around 6 meters. The bottom of the ship was flat and under normal load the mean draft was 1.20 meters (lower Seine) and around 50 centimeters (upper Seine). The bow and stern of the ship were bounded in a semicircle.

The actual movement on the chain took place via a drum winch , whereby the chain was guided several times over two drums arranged one behind the other. Each ship was also provided with two screws so that it could move freely with the chain dropped. The operating crew consisted of seven people, four of whom were on the deck ( captain , two helmsmen , a cabin boy ) and three at the engine ( machinist and two stokers ).

A chain tugboat typically pulled ten to fifteen loaded boats upriver at a time. Depending on the conditions of the river, it could have pulled twenty, but a police ordinance of May 24, 1860 limited the length of a towing formation to 600 meters.

Canalization of the lower Seine and end of the chain navigation

Between 1838 and 1868 the lower Seine was expanded everywhere to a minimum fairway depth of 1.60 meters. For this, the flow range in different separate sections through locks (was postures ) divided. The locks were intended for ships with a length of 50 meters and a width of 8 meters. This improved the situation on the lower part of the Seine between Paris and Rouen for the free-moving paddle-wheeled steamers of the Compagnie de touage et remorquage de l'Oise , known under the name "Guêpes" (wasps) , which represented increasing competition for the chain tractors .

However, since the driving depth of 1.6 meters soon proved to be insufficient, a law of 1878 decided to expand the lower Seine to a minimum depth of 3.2 meters. The state-run reconstruction of the line to Paris was completed in its entirety by 1886. Large locks (141 meters long and 11.94 meters wide) were also set up at each weir , in which either six ships 45 meters long and 8 meters wide or nine peniches 38.5 meters long and 5 meters wide could pass. The old locks remained and served empty or less loaded ships. The lock in Bougival near Paris, with a length of 220 meters, was designed to allow entire tow trains consisting of chain tugs and 15 pinasses to pass through at once. This made sense because in this section of the river both the ships to the Seine estuary and to the Belgian border operated.

In the arid summer months, the movable weirs were mostly closed, guaranteeing the full water depth of 3.2 meters with a relatively low flow speed of 0.5 meters per second. In the water-rich winter months, when weirs were partially to fully open, a travel depth of 3.2 meters was always guaranteed. Overall, after the Seine was expanded, tug shipping was interrupted on a maximum of 12 days a year (e.g. due to ice drifts or extreme floods ). As a result of the canalization work, the movement of goods could be increased from 2.24 million tons in 1879 to 3.55 million tons in 1890.

The canalization changed the profile of the river significantly. The former superiority of chain shipping was no longer given, apart from times of flooding. In addition, improved steam engines significantly increased the performance of the free-moving tugs. However, this new technology could not be built into the old chain tow steamers. The river current was no longer sufficient to allow it to drift on the descent and the ships were also dragged down the valley by the paddle steamers and screw steamers, which were much more suitable for this task than the chain tugs. The share of chain shipping in freight traffic then decreased from originally 97% to around 50% in 1892.

One last attempt to make chain shipping competitive again was made by the French engineer de Bovet. He developed a new chain hoist based on the then still young electrical engineering . The chain was only looped three-quarters around the chain drum and the necessary adhesion was provided by electromagnetic forces (→ main article: chain tow ship ). In 1892 the company Touage et Remorquage sur la Seine et sur l'Oise (TRSO), which had emerged in 1885 from the Compagnie de Touage de la Basse-Seine et de l'Oise , put a total of four chain tractors of this type after a three-year test phase a. The new technology helped to significantly reduce the number of continued fractions. In addition, the new tugs could drive down to the valley without a chain and even be used as full-fledged screw tugs on this route. In the years that followed, the company had five tugs built of a similar design, but smaller in size. They should be used on the Oise and the Oise side canal. However, the chain was no longer designed in this area and the ships were used as pure screw tugs. De Bovet's progressive invention came too late to stop the decline of chain shipping on the northern French waterways. Nevertheless, it was not until 1931 that the last chain steamers on the Seine were decommissioned. There were four steamers based on the de Bovet principle and two examples of the older design.

Chain shipping on other rivers

The company Le touage de l'Yonne received the concession in 1873 for the 93 kilometer stretch on the Yonne from Montereau (mouth of the Yonne into the Seine) to Auxerre . Initially, however, the towing service only extended to Laroche because the canalization of the Yonne between Laroche and Auxerre was not yet over.

From 1836 the water of the Loire was dammed downstream from Saint-Léger-des-Vignes near the confluence of the Aron river . This should create sufficient water depth above the weir to allow the boat to cross the Loire from the Canal latéral à la Loire (Loire Lateral Canal ) to the Canal du Nivernais or back. The crossing could not be ensured by this measure alone and Charles Semé proposed on March 6, 1869 that this section of the river, almost two kilometers in length, be linked by chain tugs. In 1870, the first of the chain tractors operated on this route, it had an output of 18 kW (25 hp) and operated with steam. His successor replaced the chain steamer in 1907. From 1933 the chain tractor Ampère V came with two diesel engines with an output of around 15 kW (20 hp ) and 7 kW (10 hp). These drove a generator that fed an electric gear to move the chain. Due to the increasing motorization of the ships, the chain tug was used less and less and was taken out of service in 1974 due to insufficient demand. It can now be viewed as part of an information center in Saint-Léger-des-Vignes.

Chain shipping was also tested on rivers whose source is in the Alpine region . The floods were much stronger here than on the Seine and carried large amounts of sand and rubble with them. On the Rhône , it was found that this river had too many sharp bends and that the chain was buried in large stretches of sand and rubble by floods. Sometimes individual sections of the chain had to be abandoned. Instead of chain steamers, eight rope tugs were used on the Rhône . For the same reasons, attempts at chain navigation on the Saône also failed .

Chain shipping on canals

In France there was a strong effort to build a network of shipping canals that would connect the east and south of France with Paris and the lower Seine, from which they are separated by a watershed . The canals therefore had to be provided with a system of locks through which the differences in level could be overcome. The highest section of the canal, also known as the apex section, was supplied with water via reservoirs that compensated for the water loss during locks. The apex position had to be long enough so that the water level did not change significantly during sluice operations. Due to the terrain, several canals in France are very narrow in this area and can therefore only be used with one ship. Deep cuts or channel tunnels make it difficult to create good towpaths here .

With an increasing cross-section of the ships, the resistance increases disproportionately on narrow single-nave canal sections of the apex postures, since the water between the ship and the canal wall has to flow backwards. Compared to two-aisled sections of the canal, around four times the pulling force is required for the canal dimensions that are predominant in France. If the towing vehicle generates additional currents, the resistance increases significantly. Experiments on the very narrow Canal du Nivernais are said to have shown this. A freely moving tugboat with three barges attached is said to have required an output of 52 kW (71 PS) for a speed of 0.6 meters per second (2.1 kilometers per hour). A chain tractor with only 7 kW (10 HP) is said to have reached the same speed.

In France, therefore, chain ships were often used to transport the canal tunnels. Due to the insufficient ventilation of the tunnel system, the electrically operated chain tugs were still used after the introduction of self-propelled motor ships and some of them are still in operation today.

Riquevaltunnel on the Canal de Saint-Quentin

The 5670 meter long Riqueval tunnel was built between 1801 and 1810 by order of Napoleon Bonaparte and is part of the Canal de Saint-Quentin , which connects Paris with northern France and Belgium . Initially, the skippers towed their boats themselves through the tunnel on two paths to the left and right of the canal, which took about 20 hours. Over the years horses have been used to transport ships, but the duration of the tunnel passage has hardly been reduced, as the water resistance was increased by ever larger ships. It was not until one of the two paths was removed in 1861 that the canal widened to 6.6 meters, which drastically reduced the water resistance.

From 1867, steam-powered chain vessels were used to transport ships on the 20.1 kilometer long, mostly single-aisle apex post. Within this canal section there are two tunnels 5670 and 1098 meters in length. Six state chain ships developed an output of 20 to 30 kW (25–40 hp ) each . Because of the heavy shipping traffic to Paris, very long and heavy tow trains had to be transported. The normal train consisted of 25 loaded ships, but up to 35 ships could also be pulled. The towing speed achieved with the attachment was only 0.9 to 1.1 kilometers per hour. The chain was initially 18 millimeters thick and gradually increased to 30 millimeters in the large tunnel. When driving through the large tunnel, the water level was dammed up by 25 to 45 centimeters and it took half an hour to an hour for this damming to dissipate again. During the long stay in the tunnel, people were exposed to heavy smoke pollution.

Electrically powered chain ships have been used since 1906. The chain ship is 25 m long, five meters wide and has a draft of one meter. It can pull up to 32 peniches through the Riqueval tunnel. The speed is 2.5 km / h. The chain laid in the canal is 8 kilometers long and weighs 96 tons. After a mechanical ventilation system had been installed in the tunnel and the tunnel's utilization decreased, only one of the two chain tugs is still in operation. The other chain tractor, named Ampère I, is located at the entrance of the tunnel and has been converted into the Museum of Chain Shipping (Musée du Touage).

Mauvages tunnel on the Canal de la Marne au Rhin

The Mauvages tunnel on the Canal de la Marne au Rhin was built from 1842 to 1847 and opened in 1853. From 1887, two chain steamers operated in the area of the apex posture over a length of 7.3 kilometers (4877 meters of which in the tunnel). They developed an output of 21 kW (28 HP) in tow and, with an attachment of 17 ships, reached a speed of 1.26 kilometers per hour. An electrically operated chain tractor has been operating here since 1912. He gets the electricity for the nearly five-kilometer stretch from two power lines on the tunnel ceiling. However, the tunnel already has ventilation shafts to the surface (as of summer 2008), so that an end to chain shipping is in sight.

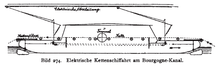

Pouilly-en-Auxois tunnel on the Bourgogne Canal

The Canal de Bourgogne connects the French rivers Yonne and Saône. In the area of the approximately 6 kilometer long apex section is the approximately 3.3 kilometer long tunnel at Pouilly-en-Auxois . Originally, the sailors had to poke their ships through the tunnel using poles , and later pull them along a chain attached to the tunnel wall, which took them up to 8 hours. From 1867, a steamboat pulled several ships through the tunnel as a towing unit .

From July 1893, electric chain tugs based on the "Galliot" system replaced the steam-powered tugs. The outflow of water when emptying the two locks at the end of the apex section each drove a turbine with a connected generator. Their total power was a maximum of 35 hp. The chain tug picked up the electricity generated by wire lines on the ceiling of the tunnel via pantographs and pulled itself and the attached boats through the tunnel. To buffer the energy, an accumulator was installed on the tug , which was sufficient for two trips back and forth. One man was enough to guide the entire tug. The electric tug had a length of 15 meters, a width of 3.2 meters and a draft of 0.5 meters. The drag chain was 16 millimeters thick. Depending on the length of the attachment, speeds of 2.5 to 4 km / h were achieved. The operating costs are said to have been 25% below those of the steamship.

The power lines running along the ceiling of the tunnel reduced the maximum headroom for the ships to 3.1 meters. The bridges in the rest of the canal were all designed for a clearance of 3.4 meters. In order to avoid this bottleneck, which resulted in particular for unloaded ships protruding far out of the water, a kind of "ship ferry" (bac-transporteur) was used from 1910. It was a floating trough having a fixed entrance threshold that was high in floating trough enough above the water and with lowered far enough below the trough water, so that an empty Péniche got over them. If the peniche to be transported was above the lowered trough in the basin, the basin was closed and the water in the basin and in the trough was drained into a ditch through a pipe so that the retracted peniche sank to the bottom of the trough. After the gates of the trough had closed, the basin could be flooded again from the channel and the trough floated open with the peniche. Even if the trough had a larger area than a peniche, due to the heavy construction of the trough it was 60 centimeters lower in the trough than self-propelled. This “ship loading” procedure took place in the corresponding basins for the trough in the outer harbors on both sides of the tunnel in Pouilly-en-Auxois and in Escommes.

The last trip of the electric chain tractor took place in May 1987. Today it is exhibited in a hall that replicates the tunnel in shape and size. Opposite is the “Institut du Canal”, an interactive museum with information boards and models on the subject of tugboat traffic and the Canal du Bourgogne. The trough was rarely used in the last few years of its operation, as the freight traffic on the canal had slackened considerably and the water level in the apex section was sometimes simply lowered accordingly for an empty peniche to pass through the tunnel.

Other channels

The Canal du Nivernais connects the two French rivers Loire and Yonne and leads through three tunnels (758, 268 and 212 meters long) at the apex. From 1899 there was a state chain shipping service on this 3.7 kilometer long section of the canal. Since there was little traffic on the canal, a chain ship powered by a gas engine ( petroleum ) with an output of about 7 kW (10 hp) pulled an attachment of 3 to 12 ships forward. It reached a towing speed of 1.2 to 2.5 kilometers per hour.

The Canal Saint-Martin is located in the northeast of Paris. On the fourth section of the canal, chain shipping has been operated since 1862 over a length of 2650 meters (1850 meters of which in the tunnel). The shipping traffic on this section of the canal was very important. The chain tractor had an output of 15 kW (20 hp) and reached a speed of 2 kilometers per hour in towing mode.

The Canal de la Meuse (then still the northern section of the Canal de l'Est ) connects Belgium with the greater Paris area. From 1880 up to four ships were towed at the same time with just one chain ship of 13 kW (18 HP). In 1887 the annual traffic was around 500 thousand tons. The route is in a short section and leads 565 meters through the Ham tunnel.

On the middle Scarpe there were two sections with chain shipping. The first was 3200 meters long and was located downstream of the Douai lock , the second was upstream of the “des Augustins” lock and was 1800 meters long. Annual traffic in 1888 on both routes was just under 1.9 million tons.

Comparison of transport costs

In the mid-19th century existed for maritime transport mainly the following techniques: towing by humans and animals as well as towage with chain steamers or paddle steamers. A comparison of the transport prices from 1863 resulted in the following statements:

The pulling of ships by humans was very strenuous and therefore took place mainly on canals in France. The average cost of transportation for this type of locomotion was about 0.0077 francs per ton and kilometer. The mean daily output was a distance of around 11 kilometers on the canals. By using horses as draft animals, the daily distance traveled on canals could be doubled to around 22 kilometers, while the average costs for transport rose to around 0.0197 francs per tonne and kilometer.

On the rivers, the costs and transport times for towing were heavily dependent on the conditions of the respective river, such as water depth and current, blockages, etc., but also on the bank design and the quality of the towpaths . In addition, the prices for towing were negotiated individually and were based on supply and demand. In 1842, for example, the cost of towing horses on the Seine was between 0.035 and 0.050 francs per ton and kilometer, while the literature gives values of 0.085 and 0.088 francs per ton and kilometer for the Yonne. The average distance that could be covered by horse-drawn train per day in 1842 was around 14.7 kilometers. Less than fifteen years later, the average distance covered per day for towing horses is given as around 20.5 kilometers. This increase in daily output by about 40% is due to the expansion of the river and the bank and also led to a reduction in costs to 0.0205 francs per tonne and kilometer, which corresponds to about half the costs of 1842.

The costs for chain shipping were set uniformly by decree and were much easier to calculate. The price was made up of two parts. The first part was based on the possible payload of the ship to be towed and amounted to 0.0035 francs per ton and kilometer. In addition, there was a second price, which was based on the actual load of the ship and was set at 0.015 francs per ton and kilometer. For a fully loaded ship, this resulted in an average price of 0.0185 francs per ton and kilometer. With half a load, however, an increased price of 0.022 francs per ton and kilometer was payable. With a chain ship, a towing formation could cover a distance of 33.3 kilometers per day.

Although the estimates could contain inaccuracies, important conclusions could be drawn from these figures. The cheapest means of transport was towed by humans, but this was restricted to canals with very slow flow rates. In addition, the enormous physical strain had to be taken into account, which often led to early death. Chain shipping on the Seine was a little cheaper than towing with horses. In addition, a tow tractor on the chain covered a much longer distance per day. The chain shipping offered fixed, calculable prices and regular transport. The transport in the towing formation also saved personnel costs, as fewer crews were required. Accidents were repaired less often and more quickly than when towing with horses.

Try with endless chains

In order to avoid the high acquisition costs of a chain or a cable, Dupuy de Lome carried out tests with an endless chain on the Rhône. The tug was equipped with its own chain. She was lowered into the water at the fore ship (bow) and lay on the river bed under her own weight. At the rear of the ship (stern) the chain was pulled out of the water and moved forward again through the chain drive over the deck of the ship. Assuming that the lower part of the heavy, self-contained chain was prevented from sliding through the riverbed , the ship pulled forward. However, this type of drive was not used economically because it only provides reasonable power transmission with a chain length that is precisely adapted to the respective water depth. If the water depth is too great, the length of the chain section that comes to rest on the river bed and thus the required friction is reduced. If the water depth is too shallow, the chain is too long and would not be elongated, but rather come to lie on the bottom in clumps. Changing river depths therefore make it difficult to steer the ship.

literature

- Gustav Carl Julius Berring: The rope shipping on the Seine . In: Centralblatt der Bauverwaltung, Berlin 1881, pp. 189–191.

- Jacques-Henri-Maurice Chanoine and Henri-Melchior de Lagrené: No. 72, Sur la traction des bateaux , In: Annales des ponts et chaussées: Partie technique. Mémoires et documents relatifs a l'art des constructions et au service de l'ingénieur, Paris 1863, pp. 229–322, ( full text in the Google book search).

- Compagnie du touage de laute Seine: Règlement de la caisse de la prévoyance. In: Réformes introduites dans l'organisation du travail par divers chefs d'industrie: patrons et ouvrirs de Paris. Paris 1880, pp. 84-85 (French).

- Maxime Du Camp: Paris, ses organes, ses fonctions et sa vie dans la seconde moitié du XIXe siècle . Volume 1, Hachette, 1879, pp. 319-332.

- M. Lermoyez: Sur le touage des bateaux dans les souterains du canal de Saint-Quentin. In: Annales des ponts et chaussées: Partie technique. No. 73, Mémoires et documents relatifs a l'art des constructions et au service de l'ingénieur. Paris 1863, pp. 323–345, ( full text in the Google book search).

- Sigbert Zesewitz, Helmut Düntzsch, Theodor Grötschel: Chain shipping. VEB Verlag Technik, Berlin 1987, ISBN 3-341-00282-0 .

Web links

- Institut du Canal de Bourgogne: Description of the chain tractor hall and hydroelectric power station , accessed on June 9, 2012

Individual evidence

- ↑ a b c d J. Fölsche: Chain shipping on the Elbe and on the Seine . In: Deutsche Bauzeitung 1, 1867, pp. 306–307 and pp. 314–316.

- ↑ a b c d e Sigbert Zesewitz, Helmut Düntzsch, Theodor Grötschel: Kettenschiffahrt . VEB Verlag Technik, Berlin 1987, ISBN 3-341-00282-0 , chap. 1 , p. 9-15 .

- ↑ a b c d e f g h Gustav Carl Julius Berring: Die Tauerei-Schiffahrt on the Seine . In: Centralblatt der Bauverwaltung. Berlin 1881, pp. 189-191.

- ^ A b Bernard Le Sueur: Le Touage - Histoire et technique . Ed .: Les Cahiers du Musée de la Batellerie. tape 34 . Conflans-Sainte-Honorine 1995, ISBN 2-909044-29-7 , p. 35-36 .

- ^ Walewski: History of the Touax group. (PDF; 142 kB) p. 3 , accessed on November 16, 2010 (English).

- ^ Dictionnaire de l'industrie manufacturière (1840) at Google Books

- ↑ a b c d e f g h MM. Chanoine and de Lagrené: Sur la traction des bateaux. In: Annales des ponts et chaussées: Partie technique. No. 72, Mémoires et documents relatifs a l'art des constructions et au service de l'ingénieur. Paris 1863, pp. 229–322, ( full text in Google book search)

- ↑ a b c Molinos and de Bovet: Pulling the ships on the canalised rivers. In: Reports: V. International Inland Navigation Congress in Paris 1892 II. Section VI, Paris 1892.

- ^ Maxime Du Camp: Paris, ses organes, ses fonctions et sa vie dans la seconde moitié du XIXe siècle . Volume 1, Hachette, 1879, pp. 319-332.

- ↑ a b c d The ship train on the waterways. The fifth international inland navigation congress in Paris in 1892. In: Alfred Weber Ritter von Ebenhof: Construction, operation and management of the natural and artificial waterways at the international inland navigation congresses in the years 1885 to 1894. Publishing house of the KK Ministry of the Interior, Vienna 1895, pp. 186-199, ( archive.org ).

- ↑ EN 1933: Le nouveau toueur: amperes V . (PDF; 917 kB) Retrieved on July 12, 2013 (French).

- ↑ Bateau remorqueur dit toueur du canal latéral à la Loire à Saint-Léger-des-Vignes . (No longer available online.) Archived from the original on May 30, 2008 ; Retrieved April 3, 2011 (French).

- ↑ Jaques de LaGarde: The French cable tug "Ardeche". In: Navalis. 1/11, pp. 43-44.

- ↑ a b Ed. Sun: Handbook of Engineering in five parts. Third part: hydraulic engineering. Volume 5: Inland navigation, shipping canals, river regulations. Wilhelm Engelmann Verlag, Leipzig 1906, p. 72.

- ^ M. Lermoyez: Sur le touage des bateaux dans les souterrains du Canal de Saint-Quentin. In: Annales des ponts et chaussées. Volume VI, Paris 1863, pp. 323-373 ( gallica.bnf.fr ).

- ↑ a b c d e f Oskar Teubert: The inland navigation - A manual for everyone involved. Volume 2, Verlag Wilhelm Engelmann, Leipzig 1918, Part 4, Section III., Ship Train. 4. Dragging on a chain or rope, pp. 268–287.

- ↑ Le Touage de Riqueval. (No longer available online.) Archived from the original on March 4, 2008 ; Retrieved January 6, 2010 (French).

- ↑ Le toueur de Riqueval fête son centième anniversaire. Fluvial magazine, June 15, 2010, accessed October 31, 2010 (French).

- ^ Heinz Dirnberger: Electric chain tractor in the tunnel of Mauvages. Retrieved January 6, 2010 .

- ^ Otto Lueger: Lexicon of the entire technology. Section Chain Towing , (2nd edition 1904–1920), accessed November 11, 2009.

- ↑ 4. The electric chain towing from Galliot on the Burgunder Canale , In: Alfred Weber Ritter von Ebenhof: Construction, operation and management of the natural and artificial waterways at the international inland navigation congresses in the years 1885 to 1894, publisher of the KK Ministry of the Interior, Vienna 1895 pp. 312-318, ( archive.org ).

- ↑ Carl Victor Suppan: waterways and inland navigation. A. Troschel, Berlin-Grunewald 1902, section: Towing on canals. ( Traction means on canals. , Electric chain navigation on the Bourgogne Canal. Pp. 419–420, archive.org ).

- ^ McKnight: France's rivers and canals. Manual for inland skippers. Verlag Rheinschiffahrt, Bad Soden / Ts. 1989, p. 222 : "A primitive vehicle, called bac or ferry, is equipped with flaps, similar to the shooters at locks. After the penis has driven in, a lowering of 60 cm is achieved by draining the water.

- ↑ Pictures and newspaper clipping with a description of a “bac transporteur” (French), accessed on June 10, 2012

- ↑ Le Petit Patrimoine: Escommes: port du canal de Bourgogne à Maconge with image “bac transporteur” (French), accessed on June 10, 2012

- ↑ Gerhard Bigell: Canal de Bourgogne , accessed 10 June 2012 Google

- ↑ The Bac at the tunnel in the Burgundy Canal ( memento from October 7, 2013 in the Internet Archive ), Inland Shipping Forum, accessed on October 4, 2013

- ↑ La halle du toueur par Shigeru Ban à Pouilly-en-Auxois , (short description with many pictures), accessed on April 10, 2011 (French)

- ^ Institut du Canal , accessed June 10, 2012

- ↑ a b c A. Schromm: The various methods of moving ships on canals and canalized rivers , In: Journal of the Austrian Association of Engineers and Architects, Volume 42, Issue 3, 1890, pages 75-79 ( online (PDF- File; 9.5 MB))

- ↑ A. v. Kaven: Lectures on engineering sciences at the polytechnic school in Aachen. Chapter III. Section comparison of transports on railways and navigable rivers. P. 78–80, Hannover 1870 ( full text in the Google book search)

- ↑ Carl Victor Suppan: waterways and inland navigation. A. Troschel: Berlin-Grunewald 1902, section: Inland navigation. ( Dampfschifffahrt. , Block Search. Means of endless chain pp 269-270, archive.org ).