Chain shipping on the Elbe and Saale

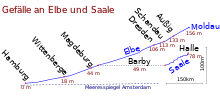

The chain cruise on the Elbe and Saale was a special type of transport by ship, the motorized in the second half of the 19th century inland navigation on the Elbe and Saale dominated. A chain tugboat pulled several barges along a chain laid in the river. Until the chain shipping since 1866 Skippers revolutionized in Germany initially on the Elbe, was towing the predominant Power upstream propelled ships. After the chain was expanded, up to 28 chain tugs drove up the Elbe over a total length of 668 kilometers ( Hamburg to Aussig in Böhmen ). From 1890, the importance of chain shipping in the area of the lower Elbe continued to decline in favor of paddle steam tugs and was completely discontinued here by 1898. It was able to survive on the Upper Elbe until 1926/27 and was then only used locally in Germany until 1943 in three short, particularly difficult sections of the Elbe. From 1943 to 1945, the only remaining route section in Germany was the short section in Magdeburg where chain shipping on the Elbe began. In Bohemia it was used until 1948. On the Saale there was chain shipping from 1873 to 1921.

Spread of chain shipping

Elbe

Before the time of chain shipping, those ships that wanted to go upstream and could not be brought forward in the current by rowing or sailing were pulled upstream. This locomotion, known as “ Treideln ” (Saxon “bomätschen”), guaranteed many people work. At many sections of the river, the ships were pulled directly from the land by the muscle strength of several men (called " Bomätscher " in Saxony ) or horses.

On June 16, 1864, the " United Hamburg-Magdeburg Steamship Compagnie " - Martin Graff was the director of this company - received the concession for chain shipping on the Elbe. The first chain tow steamer, " No. 1 " built by the company's own shipyard in Buckau based on the French model , was used for testing on August 15, 1866 in the area of the Magdeburg bridges between Magdeburg -Neustadt and Buckau . On this approximately five kilometer long section, the Elbe has a particularly high flow speed due to the cathedral rock . The tests were successful and regular operation on this route began.

Due to the high acquisition costs, the expansion of the chain by the "Vereinigte Hamburg-Magdeburger Dampfschiffahrts-Compagnie" was relatively slow. By 1868 the 51-kilometer chain was laid between Magdeburg and Ferchland , in 1872 between Ferchland and Wittenberge (77 kilometers) and only in 1874 between Wittenberge and Hamburg (165 kilometers).

The situation was different on the Upper Elbe. Responsible here was the company "Kettenschleppschiffahrt der Oberelbe" (KSO) under the direction of the engineer and general director Ewald Bellingrath in Dresden. He had clearly recognized that a revolution in shipping on the Elbe, which had previously become insignificant, could only take place with the use of modern technology. In the article Die Kettenschifffahrt auf der Elbe by A. Woldt it says about the first test drive in Dresden:

"At that time, in 1869, when the first test drive on the route from Riesa to Dresden took place under his direction, the rule of the bomber was still in full bloom, and they were so well aware of it that they were not in the least bit the competition of the Chain steamers feared. On the contrary, they even pitied him, because they expected at any moment that he would perish on one of the many dangerous rapids. But when the vehicle with the train it towed elegantly and safely passed the notorious sharp corner of the Meißener Fuhrt, the faces became noticeably longer, and finally after the horror of all horrors for shipping at the time, the dangerous passage under the The Augustus Bridge, which narrowed the river in Dresden, had been covered without the slightest damage to the tug, the bomber was overcome by the feeling of anger and enmity, and more than a stone, thrown from their midst, flew onto the vehicle. "

Just a few months later, Bellingrath applied for the Saxon, Anhalt and Prussian chain concessions, which, after tough efforts and overcoming all political and official difficulties, were granted to him in the same year (December 1870) for the Elbe stretch from Magdeburg to Schandau on the Bohemian border. As early as October 1, 1871, that is, only about ten months later, the towing operation on this 330-kilometer stretch with nine chain steamers went into operation. Later on, Bellingrath also ensured the further spread of chain shipping on other rivers in Germany and is therefore often referred to as the "father of chain shipping".

The “Prague Steam and Sailing Company” expanded the chain operation from the Bohemian border to Aussig in 1872 and started with two chain tugs. In 1879 a third chain tug was added on this route, so that two to three tow trains with an average of seven to eight barges drove upstream from the Schandau annex. In 1882 the company became the property of the "Österreichische Nordwest-Dampfschifffahrts-Gesellschaft". In 1895, the chain is said to have even reached 777 kilometers from Hamburg and across the Elbe and Moldau to Prague , although extensive and steady operation only took place on the section from Hamburg to Aussig.

In 1881 Bellingraths KSO bought the "Elb-Dampfschiffahrts-Gesellschaft" and the "Hamburg-Magdeburger Dampfschiffahrts-Compagnie" and merged with them to form the "Chain - German Elbschiffahrts-Gesellschaft" . It was headed by Bellingrath and was responsible for the entire German Elbe chain operation from Hamburg to the Bohemian border (630 kilometers).

Saale

In 1871 a “steam and tugboat association on Saale and Unstrut” was founded in Artern . The plan was to chain or rope short sections of the route. However, this company never implemented it.

On the Saale , the 21 km long route from the mouth of the Saale in Barby to Calbe was put into operation in 1873, thus establishing a connection to the chain in the Elbe. A further expansion was postponed for the time being due to the difficult fairway and the seven locks following upstream. The state of Anhalt and above all the city of Halle pushed for an extension of the chain. However, Prussia only saw an expansion as sensible if the chain would extend to Leipzig after the construction of the Elster-Saale Canal . After long negotiations, it was decided in 1881 to try to extend the chain to 105 km and thus to Halle; this was implemented in 1884.

Chain shipping on the Saale suffered a sharp decline with the outbreak of the First World War and was completely discontinued in 1921. The chain was taken out of the Saale in 1922.

Effects of chain ships on navigation on the Elbe

In the middle of the 19th century, the railways developed into a nationwide network and increasingly represented competition for towage shipping. Until then , the Elbe shipping had accepted the burden of the Elbe customs and the natural obstacles of the waterway because it was still in the Advantage was. The Elbe tariff on the route from Hamburg to Saxony was more than half, to Bohemia even 70% of the total costs. Fluctuating water levels and changes in the course of the river, as well as wind and weather, also resulted in transport delays and, not infrequently, losses of ships and cargo. The railroad transported goods faster, more reliably and, because of the exemption from duties, also cheaper than the ship. The advancing industrialization brought growth to both modes of transport, but the growth on the railroad side was significantly greater. In addition, goods with full customs duties left the Elbe and switched to rail. These goods were at the same time the higher quality goods, the transport of which had brought in the highest income. Shipping was increasingly limited to bulk goods such as pig iron, coal, guano and saltpetre . It was not until 1863 that the Elbe tariff was significantly reduced and completely abolished in 1870.

Chain towing revolutionized Elbe shipping, which until then had been shaped by towing for centuries. The sailing operation was discontinued or only used as a makeshift. The heavy rigging became superfluous and could be replaced by additional cargo. The crew on the barges was reduced by more than half. The skipper became independent of many unfavorable weather conditions. The number of possible journeys by a ship increased almost three times. Instead of two trips, six to eight trips were made annually or up to 8000 km instead of 2,500 km a year. The delivery times were accordingly shortened and adhered to more reliably and the costs fell, so that some goods that had been transferred to the railways switched back to the cheaper waterway.

Similar changes could very well have been made by paddle steamers , but the concessions for chain shipping guaranteed the skippers constant transport at fixed prices and thus sufficient security to stop sailing and switch to towing. The size of the barges, which at that time usually carried a load of about 100 tons, could be enlarged. About ten years after the introduction of tugboat shipping, barges with a typical load capacity of around 500 tons were built.

The amount of freight remained practically constant over a very long period between 1830 and 1874. The ships transported around 7 to 8 million quintals (350,000–400,000 tons) uphill from Hamburg every year . The shipping traffic down the valley to Hamburg was somewhat lower at around 6 million hundredweight (300,000 tons). After the completion of chain shipping, the amount of freight rose steadily and after ten years it had roughly quadrupled, namely 28 million quintals (1.4 million tons) uphill and 24 million quintals (1.2 million tons) downhill.

Concession Conditions and Competition

In order to be able to operate the chain shipping, the company responsible for the chain towing operation needed a license from the responsible state in which, among other things, the rights and obligations towards the boatmen were regulated. Paragraphs 10 to 13 of the license conditions for the “chain towing of the Upper Elbe” (KSO) regulated the tariff. According to this, every tariff adjustment required the approval and approval of the Ministry of Finance. Tariffs were also set for at least one year and could not be changed during this time. The transport fees were to be calculated in proportion to the towing distance, regardless of the goods being transported. In addition, the chain shipping companies were critically monitored by the Treasury. Every five years it was checked that the annual net income did not exceed a value of 10 percent of the capital verifiably invested in the company. If the profit was too high, the tariffs were reduced by the Ministry of Finance.

As a result of these provisions, the freedom of the chain shipping companies was very limited and they could not react so flexibly to changes in the market. In contrast to chain shipping, the other types of towing were able to set the tariffs freely according to supply and demand, adapt the costs to the amount of freight transported or negotiate special conditions with individual customers.

However, paragraphs 6 and 9 of the concession deed were even more drastic. The entrepreneur was required to transport each loaded or unloaded vehicle in the order in which it was registered, regardless of the route over which the vehicle was to be towed. The chain shipping company was allowed to transport goods or vehicles on its own account, but under all circumstances, third-party vehicles, even if they were registered later, had priority in the transport. That virtually led to the termination of the company's own cargo shipping business.

Chain shipping was in direct competition with paddle steamers and the railroad. However, the two German chain-towing companies in Magdeburg and Dresden also competed with each other. The "United Hamburg-Magdeburger Dampfschiffahrts-Compagnie" had sold all previous paddle steamers in the early 1870s to introduce chain towing between Magdeburg and Hamburg. However, this made it impossible for her to tow above Magdeburg. All of the towed customers who wanted not only to Magdeburg but further up the Elbe could only be served as far as Magdeburg. Here the skippers were left to their fate, who as a result often had to wait several days for further transport. The Dresden KSO acted aggressively and opened its own shipping office in Hamburg with the aim of retaining the towed customers in Hamburg. A paddle steamer was used as a towing force for the Hamburg – Magdeburg route and two more were contracted. The boatmen were thus guaranteed seamless transport from Hamburg to the Bohemian border.

After the pressure of competition from the paddle steamers had increased, the KSO succeeded in 1879 to relax the concession. The government approved the amendment that the company was no longer obliged to tow such vehicles, the owners of which were themselves commercially wheeled towing. She was also allowed to adjust the tariff rates herself as needed. The enormous competition had an unfavorable influence on the results of the two chain companies, and in 1880 these two companies came closer together and joint contracts were concluded. In 1881 the KSO bought the "Elb-Dampfschiffahrts-Gesellschaft" and the "Hamburg-Magdeburger Dampfschiffahrts-Compagnie" and merged with them on January 1, 1882 to form the "Chain - Deutsche Elbschiffahrts-Gesellschaft" .

Technical Equipment

Chain

The chain for chain towing on the Elbe was mainly imported from England by all three chain shipping companies. The Magdeburg company also had part of the chain from Hamburg to Wittenberge from France. The reason for the import was the necessary high quality of the fire welding of the pre-bent chain links. This could not be guaranteed at the beginning of the chain shipping in Germany due to domestic production. In 1880, the Oberelbe chain company tried to produce the chain independently in its shipyard, the Übigau shipyard . 3500 meters of chain were made. However, a consistently high quality in mass production could not be achieved.

The chain in the Elbe was a seamless ship chain, the chain links of which were 4.5 times the length of the round iron thickness. At the beginning of chain shipping on the Elbe, a 22 millimeter chain was usually used. On some sections of the route, however, a 25 millimeter chain was used in some cases. A low carbon round iron was used as the chain material.

On the 330-kilometer stretch from Magdeburg to the Bohemian border, the chain had stretched and worn out by a length of 7,500 meters in just three years. Many chain sections had to be replaced prematurely, so that after ten years only about 12 kilometers of the original chain were still in use. Often the badly worn chain broke and had to be repaired on the chain ship. The chain sections were replaced by chains with thicknesses of 25 and 27 millimeters.

To facilitate the exchange of chain sections, there were shackles (called “chain locks”) at intervals of 400 to 500 meters , on which the chain should be easier to open. These “chain locks” should also be opened when two chain ships meet on a chain. Corrosion and stretching of the chain, which also occurred with normal use, meant that the chain locks could no longer be opened, so that one switched to simply separating the chain on a normal chain link. For this purpose, a link was placed upright on the boom with pliers and compressed with a sledgehammer to such an extent that it could be torn open and widened with a crowbar until the next chain link could be pulled through. After completing the maneuver, the chain was closed again with a chain lock. If two chain vessels met, a complicated evasive maneuver was necessary in which the chain was transferred to the other tug via an auxiliary chain, the so-called interchangeable chain, which each chain tug carried. This maneuver meant a delay of at least 20 minutes for the towing formation going uphill, while the downhill vessel suffered a loss of time of around 45 minutes as a result of the maneuver.

Later, when the frequency of encountering the chain tugs increased, the chain tugs (No. 5-10, XXI and XIII) were given double propellers with which they could go down to the valley with almost no loss of time. Only here did they have to shackle themselves again.

Chain tow steamers

The chain tow steamers on the Elbe, built at the shipyards in Magdeburg , Dresden , Roßlau and Prague , were adapted to the conditions of the unregulated Elbe and were able to convert their relatively low engine power into towing power with good efficiency.

The chain steamer No. 1 was built by the machine works and shipyard of the United Magdeburger Schiffahrts-Compagnie in Magdeburg-Buckau . With the exception of the hood, it was constructed entirely of iron, 51.3 m long, 6.7 m wide and 48 cm draft. At both ends it had rudders that could be moved together from the center of the ship. With the help of this control and two movable arms attached to each end of the ship, which held the chain between rollers and were rotatable by almost 90 ° in the horizontal direction, it was possible to steer the ship in a direction other than the direction of the pull chain without this the winding of the chain was disturbed. This was of great importance for the use of the chain ship on curved streams. On the deck of the ship there were two drums with a diameter of 1.1 m and a mutual axis distance of 2.6 m, each of which was provided with four grooves. The chain, which was lifted out of the water by the ship's bow , ran in a sloping, ascending channel with guide rollers to the drum winch . There it looped around each drum 3½ times, going from the first groove on the first drum to the first groove on the second drum, then to the second groove on the first drum, and so on. Finally she was led in a sloping gully to the stern of the ship and sank back into the water there.

The following chain ships were basically similar, but they differed slightly in their dimensions or the structure of the steam engine. The typical length of the ships was 38 to 50 meters, their width about 7 to 7.5 meters. From 1872 onwards, most of the chain boats received an additional double screw drive, which enabled them to carry out the descent “freely” - that is, without a chain. That spared the chain significantly.

Another change came after Bellingrath realized that the chain breaks were caused in large part by wear and tear on the drum winch. In 1892 he designed the chain gripper wheel named after him . The first newly built chain ship equipped with it was the Gustav Zeuner in 1894 . It was also equipped with a new type of drive in the form of two water turbines according to Gustav Anton Zeuner (the forerunner of today's water jet drive ), with which the ship could be steered and went down to the valley without a chain. With a length of over 55 meters and a width of over ten meters, the ship was larger than the previous chain ships and in its dimensions already approached the smaller paddle-wheeled steamers.

For the Saale with its many tight turns and narrow locks, on the other hand, you needed small chain ships less than 40 meters long and less than 6 meters wide. Only one of the older chain ships on the Elbe met these requirements and was used on the lower Saale from 1873. After the chain was extended to Halle, chain ships built for other rivers were bought and new buildings built.

Rates

The tariffs for barges were set within the concession. The costs resulted from a basic fee for the towed vehicle and an additional fee for the load. The tariff was also dependent on the river section traveled. While higher tariffs of 130% of the normal tariff were required in the more sloping sections of Bohemia, reduced tariffs of only 50% of the normal tariff applied for the Hamburg - Magdeburg route.

Overall, it was found for the skipper in general that he only made a small profit on the journey uphill (even worked at a loss on an empty journey), while he obtained most of the profit from transports down the valley.

The end of chain shipping on the Elbe

| year | Chain tractor | Wheeled tractor |

|---|---|---|

| 1882 | 31 | 28 |

| 1903 | 35 | 58 |

| 1922 | 23 | 63 |

| 1927 | 17th | 77 |

The Elbe shipping suffered greatly from the various trade customs. At the trading center, a skipper could not request the immediate unloading of his cargo, but on the contrary had to allow 12 to 14 days of unloading time, depending on the quantity transported. From this it emerged that of the season lasting around 300 days, only around 75 days were used for the actual journey on the Elbe, while 225 days were used for loading, unloading and lying under load. An improvement in delivery times through higher towing speeds was only possible to a limited extent as long as the merchants used the cargo ships as cheap magazines.

Chain shipping was superior to other types of ship operation wherever difficulties arose for shipping, such as rapids, sharp bends in the valley path and shallows. At the time of chain shipping, the maximum permissible shipping depth at medium water levels on the route from Aussig to the Austrian border was just 54 centimeters, between the Austrian border and Magdeburg it was 60 to 65 centimeters. Below Magdeburg to the mouth of the Havel, the shipping depth increased to 90 centimeters, further down the Elbe, a draft of 90 to 100 centimeters could be achieved at medium water levels. With the increase in traffic, more and more current regulations came about: the gradients were more and more evened out, the curvatures of the river and the shallows were reduced, and the advantages of chain shipping were reduced. On the other hand, the paddle steamers made progress and their coal consumption decreased. At the same time, progressive current regulation made larger and more powerful paddle-wheeled steamers possible.

Another problem for the competitiveness was the high depreciation of the chain companies. The chain itself tied up a lot of capital and had to be replaced after about ten years.

In the 1890s, more powerful side wheel tow steamers increasingly competed with chain towers. This primarily affected the sections of the route downstream below Torgau with a lower gradient of less than 0.25 ‰ and high water depth. The "chain - German Elbe shipping company" itself upgraded its fleet here more and more to the more promising paddle steamers and decided in 1884 to stop renewing the chain between Hamburg and Wittenberge. Chain steamers were used less and less from 1891 below Magdeburg, until in 1898 the Prussian ministers approved the suspension of chain shipping on the approximately 270-kilometer stretch between Hamburg and Niegripp (north of Magdeburg) and the chain was lifted in this section.

On the steeper stretches in Saxony and Bohemia, the chain steamers were able to hold their own against the paddle steamers for a little longer due to the shallower water depth and the higher flow speed. But here, too, profitability increasingly shifted towards wheeled tractors. In addition, there was the economic crisis of 1901/1902, which led to the fact that in December 1903 the previously competing towing companies consisting of wheeled and chain tugs - "Ketten" with the "Dampfschleppschiffahrts-Gesellschaft united Elbe- and Saale-Schiffer" - merged January 1904 the "United Elbe Shipping Society" formed. Chain towing lost more and more importance. In the years 1926/27 the chain shipping was stopped in further large sections and the chains were lifted.

In Germany, chain shipping was still in operation on three difficult sections of the Elbe until 1943. After that, only two chain steamers were in service in Germany on an eleven-kilometer stretch near Magdeburg until they were destroyed on January 16, 1945 in a heavy air raid on the city. Chain shipping in Bohemia ceased in 1948.

The disused chain steamers were either scrapped or converted into workshop ships, steam winches, barges or piers. The Gustav Zeuner is the last remaining chain ship on the Elbe. It was restored over several years as part of a job creation measure in Magdeburg and opened as a museum ship after the work was completed.

Museums with exhibitions on chain shipping on the Elbe

In Dresden Transport Museum a model of the chain steamer is No. 1 and the chain steamer "Gustav Zeuner" exhibited together with part of the original chain. In addition, the function of the chain ship is explained with a film.

In the Elbe Shipping Museum in Lauenburg , part of the exhibition is dedicated to chain shipping on the Elbe. From August 22, 2003 to January 31, 2004, a large special exhibition was held here in honor of the founder of chain shipping under the title Ewald Bellingrath - A Life for Elbe Shipping . This special exhibition was then shown in several other museums.

The chain steamer Gustav Zeuner was completed after three years of restoration on November 11, 2010 and officially released as a museum ship. The ship is on land in the former trading port basin in Magdeburg. Over 150 workers were involved in the project run by the city of Magdeburg and the ARGE job center.

literature

- Julius Fölsche: Chain shipping on the Elbe and the Seine. In: Architektenverein zu Berlin : Deutsche Bauzeitung , Volume 1, Carl Beelitz, Berlin 1867, pages 306–307 and 314–316 ( beginnings of chain shipping on the Elbe and Seine in the Google book search).

- Description of the first German chain ship between Neustadt and Buckau. In: Architects' Association in Berlin: Deutsche Bauzeitung , Volume 2, Carl Beelitz, Berlin 1868, page 100 ( description of the 1st German chain ship between Neustadt and Buckau in the Google book search).

- Decree concerning the practice of chain shipping on the Upper Elbe; from October 20, 1869. (No. 83) In: Law and Ordinance Gazette for the Kingdom of Saxony from 1869. Meinhold, Dresden 1869, pp. 299–304 ( digitized version of SLUB Dresden ).

- A. Woldt: Chain shipping on the Elbe . In: The Gazebo . Issue 15, 1882, pp. 251-254 ( full text [ Wikisource ]).

- Rope. In: Meyers Konversations-Lexikon , Volume 15, 1888.

- Sigbert Zesewitz, Helmut Düntzsch, Theodor Grötschel: Chain shipping. VEB Verlag Technik, Berlin 1987, ISBN 3-341-00282-0 .

- Karl Jüngel: The Elbe - story about a river. Anita Tykve Verlag, 1993, ISBN 978-3-925434-61-7 .

- Hans-Joachim Rook (ed.): Sailors and steamers on the Havel and Spree. Brandenburgisches Verlagshaus, 1993, ISBN 3-89488-032-5 .

- Association for the promotion of the Lauenburger Elbeschifffahrtsmuseum e. V. (Ed.): Ewald Bellingrath - A life for shipping. (= Publications of the Association for the Promotion of the Lauenburger Elbschiffahrtsmuseums eV Volume 4), Lauenburg 2003.

- Sigbert Zesewitz: The chain shipping on the Elbe and Saale. Sutton Verlag, Erfurt 2017, ISBN 978-3-95400-764-6 .

Web links

- Ewald Bellingrath - a life dedicated to shipping on the Elbe. Elbe Shipping Museum Lauenburg, archived from the original on October 29, 2007 ; Retrieved December 10, 2009 .

- The chain - a chapter in shipping on the Saale. Preisnitzhaus e. V., accessed on December 18, 2009 (information brochure on the traveling exhibition).

Individual evidence

- ↑ a b c The chain - A chapter of shipping on the Saale. Preisnitzhaus e. V., accessed on December 18, 2009 (information brochure on the traveling exhibition).

- ↑ a b c d e f g h i Dr. Erich Pleißner: Concentration of freight shipping on the Elbe. In: Journal for the entire political science. Verlag der H. Lauppschen Buchhandlung, Tübingen 1914, supplement L, pp. 92–113, digitized version on archive.org

- ↑ a b A. Woldt: The chain shipping on the Elbe . In: The Gazebo . Issue 15, 1882, pp. 251-254 ( full text [ Wikisource ]).

- ↑ a b c d Ewald Bellingrath - a life for the Elbe shipping. Elbe Shipping Museum Lauenburg, August 31, 2003, archived from the original on October 29, 2007 ; Retrieved December 10, 2009 .

- ↑ a b c d e f g h i j k l Sigbert Zesewitz, Helmut Düntzsch, Theodor Grötschel: Kettenschiffahrt . 1st edition. VEB Verlag Technik, Berlin 1987, ISBN 3-341-00282-0 .

- ↑ L. Franzius, H. Garbe, Ed. Sun: Handbook of Engineering in five volumes. Volume 3: Hydraulic engineering. Wilhelm Engelmann, Leipzig 1900, pp. 134-138, digitized version on archive.org

- ↑ Dieter H. Steinmetz: History of the city of Calbe on the Saale. (7th section): 1870/71 to 1914 , accessed on September 23, 2012

- ↑ a b Hermann Schwabe: The development of German inland shipping up to the end of the 19th century. (PDF; 826 kB) in: German-Austrian-Hungarian Association for Inland Shipping, Association publications, No 44.Siemenroth & Troschel, Berlin 1899.

- ↑ Sigbert Zesewitz, Helmut Düntzsch, Theodor Grötschel: chain shipping. VEB Verlag Technik, Berlin 1987, ISBN 3-341-00282-0 , from page 251.

- ↑ Dresden Transport Museum: Unique Chain Fund in the Elbe , accessed on 12 January 2010 ( Date 7 May 2005 ( Memento of 7 May 2005 at the Internet Archive ) in the Internet Archive )

- ^ Ingo Klinder (Magdeburg Elbe Schiffer Association): Last chain steamer is being restored in Magdeburg , published on September 25, 2009, accessed on January 12, 2010

- ↑ The bow and stern of a chain tug did not differ from one another in terms of their design, as the ship never turned, but picked up the chain at one end when traveling uphill and the other when traveling downhill.

- ^ Roping . In: Meyer's large conversation lexicon. A reference book of general knowledge. 4th edition. Verlag des Bibliographisches Institut, Leipzig and Vienna 1885–1892, Volume 15, pp. 543–544

- ↑ a b The ship train on the waterways. The fifth international inland navigation congress in Paris in 1892. In: Alfred Weber Ritter von Ebenhof: Construction, operation and management of the natural and artificial waterways at the international inland navigation congresses in the years 1885 to 1894. Publishing house of the KK Ministry of the Interior, Vienna 1895, pp. 186-199, online: Internet Archive

- ^ Karl-Heinz Fröhlich: Black colossi stomped on the Elbe. (PDF) History and Stories. Dorfkurier der Gemeinde Hirschstein, September 2007, p. 4 , archived from the original on October 26, 2007 ; Retrieved September 23, 2012 .

- ↑ a b About the negotiations of the V international inland shipping congress in Paris 1892. In: Journal of the Austrian Association of Engineers and Architects , vol. 45, issue 3, Vienna 1893, pp. 39–45; kobv.de (PDF; 13.4 MB)

- ^ Karl-Heinz Kaiser: Museum ships in Magdeburg. On November 11th, the extraordinary witness of the Elbe shipping is officially inaugurated. Magdeburger Verlags- und Druckhaus GmbH (Volksstimme), October 27, 2010, accessed on October 27, 2010 .

- ↑ Facts and figures “Gustav Zeuner” chain tow steamer