Chain tow ship

Chain tugs (including chain tractors , chain steamer , chain vessels or French toueur called) were in the second half of the 19th and in the first half of the 20th century in many European rivers vessels operating that ran along a longitudinal riverbed laid steel chain forward and founded the chain shipping . The river boats, each powered by a steam engine, pulled several barges behind them.

The chain was lifted out of the water at the bow of the ship via an extension (boom) and led across the deck along the ship's axis to the chain drive in the middle of the ship. The power transmission from the steam engine to the chain usually took place via a drum winch. From there the chain led over the deck to the boom at the stern and back into the river. The lateral mobility of the boom and the two rudders attached to the front and rear made it possible to put the chain back in the middle of the river even when the river bends.

history

The chain shipping revolutionized the beginning of industrialization in the second half of the 19th century, the inland shipping and dissolved the hitherto customary towing from. The chain drive of the chain steamers made optimal use of the still low power of the steam engines of that time. In addition, the ships were particularly adapted to the difficult conditions of the rivers at that time with strong currents and shallow water. This led to the spread of chain shipping on many rivers in Europe. In the first half of the 20th century, the increasingly powerful paddle steamers replaced the chain steamers, especially since the canalization of rivers further increased the advantages of paddle steamers.

The first developments and technical preliminary stages for chain ships occurred up to the middle of the 19th century, especially in France (→ main article: chain ships ) . The French chain steamer "La Ville de Sens", which was built by the German engineer M. Dietz in Bordeaux around 1850 and was used on the upper Seine between Paris and Montereau, became the prototype of all later chain steamers on the Elbe , Neckar and Main . Its technically very well developed functional principle and the mechanical equipment have become the model for all subsequent European chain steamers.

Shape of the ship's hull

The deck of the symmetrically constructed ships reached almost to the surface of the water at the bow and stern of the ship. This design reduced the force required to lift the drag chain at the bow of the ship, thereby also reducing the draft at the bow of the ship. The greater height in the middle of the ship also made it easier to accommodate the steam engine. This shape of the ship deck is typical of all chain tow ships built later.

Chain tugs were preferred on rivers with shallow water and strong currents. This results in the flat, level floor of the ships. Chain ships optimized for particularly shallow water depths had a draft of only 40 to 50 centimeters when unloaded . Fully loaded with coal, the draft increased to about 70 to 75 centimeters. This shallow draft made it possible to transport ships by ship even in the dry summer months when the water level in the rivers could be very low.

Shorter chain ships (length 30 to 40 m, width 5 to 6 m) were more manoeuvrable and had advantages on narrow rivers with many bends, for example on the Saale . Longer chain ships (length 45 to 55 m, width 7 to 10 m) were advantageous on rivers that have a relatively large water depth, such as the Elbe. The deeper a body of water, the greater the proportion of the force that has to be used to lift the heavy chain. The bow of the ship is pulled down harder. This effect is less with larger chain vessels.

The hull itself was made of iron or wood and could withstand light grounding. If there was a leak anyway , the interior of the hull was also separated into closed areas by several watertight bulkheads , which prevented the ship from sinking. In addition to the steam engine and the coal bunkers, the crew quarters were also located below deck.

In chain shipping, the chain lay only 'loosely' in the river bed over long stretches of several hundred kilometers. The dead weight of the massive chain of around 15 kilograms per meter or 15 tons per kilometer and the natural entanglement with sand and stones in the river bed were sufficient as a counter bearing so that the chain tug with the attached barges could pull itself along the chain. The water carried the weight of the ships, while the chain only had to absorb the propulsive force. The chain was only anchored at the two extreme ends of the route so that the ships could go there.

The lateral laying of the chain was more of a problem. At river bends there is a tendency to pull the curved chain more and more "straight" and thus move it further towards the inner bank. To prevent this, the chain ships were fitted with large, powerful rudders at the front and rear. Some of these oars were over four meters long and were operated with the help of steering wheels located on deck.

At the ends of the ship, the chain for further guidance ran over outriggers that protruded far beyond the end of the ship. This prevented the chain from colliding with the long oars. The booms were movably mounted and could be swiveled sideways using a hand crank. This allowed the ship to be aligned at an angle to the chain direction. This also improved the possibility of placing the chain back in the middle of the river.

The booms were also equipped with a chain catcher to prevent the drag chain from running off if the chain broke. If the ratchet could not be hooked into the chain quickly enough, the chain would expire and disappear into the river. It then had to be laboriously located and retrieved with a search anchor.

Chain drive

With the chain tugs of the first generation, the chain ran over chain drums attached to the side of the ship. If the current was very strong or if there were problems lifting the chain due to siltation or obstacles on the river bed such as large stones, the ship could sway significantly and list. In later chain tugs, the chain drive was therefore always arranged in the center of the ship.

Drum winch

The older chain tugs on the Elbe , the chain steamers on the Neckar and the three chain tugs belonging to the Hessian Mainkette AG on the Main used a drum winch for power transmission. In order to ensure the necessary adhesion of the chain to the drive drums, the chain in the middle of the ship was wrapped several times around two traction drums arranged one behind the other. The chain ran in four or five grooves and was passed alternately over the front and rear pulley.

The disadvantage of this method was numerous warp breaks. These were not caused by an overload on the chain of roads due to the size of the tow trains. Calculations in this regard showed that even if the chain links were worn to half the original cross-section, this force would not have led to a break.

Rather, the front pulling drum wore more and more from friction. As soon as the diameters of the two drums were unequal, however, more chain was wound on the rear drum than could be unwound on the front. This created tensions on the drums and between them that could become so great that the chain links could no longer withstand this tensile load and the breaking limit was exceeded.

This effect became particularly problematic when the chain had twisted itself, i.e. H. came to an edge or even formed a knot. This increased the wrapping radius by up to 25%, whereby the elastic limit of the chain was already reached at 5%.

The drag force was transferred from the drums to the chain only through friction. The chain could slip if there was frost or ice. Here one made do with hot water that was poured over the drums.

Another problem with the drum winches was the relatively long chain length of 30 to 40 meters, which was necessary due to the multiple wrapping of the two drums. If the chain tractor was only used for uphill travel, this amount of chain could not simply be thrown off, otherwise after a certain operating time the entire chain would be piled up above the actual operating section and would be missing at the beginning. Attempts were made to counteract this inconvenience by always taking a corresponding piece of chain down the valley with the chain tractor and inserting it again at the beginning of the chain. This resulted in continuous migration of the chain, which made it difficult to control the wear and tear in particularly endangered river sections such as rapids. In particular, consciously used, reinforced chain sections hiked ever further uphill. It was also relatively difficult to throw off the chain when two chain ships on the chain met, due to the multiple looping of the two drums.

Many of the chain steamers without their own additional drive had a different gear ratio for the ascent and descent. This was designed for high tractive effort when driving uphill, while a higher speed could be achieved when driving downhill.

Chain gripping wheel

The chain gripper wheel (also called chain gripper wheel after Bellingrath) was designed in May 1892 by Ewald Bellingrath , the general director of the German Elbe shipping company "Chain" in Übigau , in order to avoid the problem of constant chain breaks. This principle was used in various chain vessels on the Elbe, as well as in the eight chain vessels of the Royal Bavarian Chain Shipping Company on the Main.

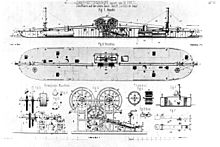

The idea of the mechanism was to use only a drum or wheel for the actual drive and not to wrap the chain around several times, but only to loop it around partially (Figure 1). The construction should grip the chain securely without it starting to slip. This should also work with changing chain strengths and different lengths of the individual chain links and regardless of their location (e.g. sloping or edgewise storage). The construction should react without errors even if there is a knot formation in the chain.

The chain was fixed in the drive area by many lateral pins (gripping device) which hooked into the chain as moving parts on the left and right (Figure 2). Critics initially feared that the many moving individual parts of the "gripping device" could wear out quickly. However, this fear was refuted in a three-year experiment (started in May 1892). On the contrary, by using the "gripping device" the power transmission could be improved, so that more ships could be transported in a towing formation. As a consequence, all of the new chain towing vessels built by the chain in Übigau were equipped with handwheels.

At least in the chain ships on the Main, the chain gripping wheels were replaced by drum winches from 1924 onwards, as the former were too prone to failure.

Electromagnetic drum

Another approach to reduce the extent of chain fractions and the wandering of the chain originated in France and was used on the lower Seine near Paris from November 1892 . The inventor de Bovet developed a technique to increase the friction of the chain on the drive drum using magnetic forces. Here, too, the chain only touches the pulley with a three-quarter turn. The chain was fixed on the pulling roller by magnetic forces caused by electromagnets built into the pulling roller. The electricity required for this was generated by an approx. 3 HP dynamo driven by its own motor .

In a test with an old chain weighing 9 kg per meter, the magnetic force was sufficient to generate a holding force of around 6000 kg, despite the slight looping of the pulley.

Additional drives

In addition to the chain drive, most of the chain ships built later had an additional drive. This allowed the ships to move without a chain, which was mainly used during the descent. The downhill travel time was reduced by higher speeds and the elimination of the time-consuming and complicated encounter between ships going uphill and downhill on the same chain. In addition, the chain was spared.

Water turbines

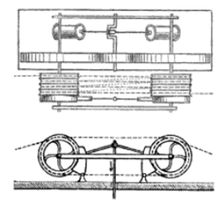

From 1892 water turbines according to Zeuner were used in chain ships on the Elbe . They are a forerunner of today's water jet propulsion . In addition to the faster descent, the additional drive also enabled direction corrections while driving on the chain and facilitated turning maneuvers. Chain ships with water turbines were used on some chain ships on the Elbe and on the Bavarian chain ships on the Main .

The water is sucked in through two rectangular inlet openings in the side wall of the chain steamer. It then flows through the turbine located inside the ship's hull. The turbine accelerates the water and pushes it through the rear-facing water outlet openings in the side of the ship. The outflowing water drives the ship forward (top picture of the side view). To change the direction of travel, the deflector (reflector) is swiveled in and the water is diverted in the opposite direction (lower picture of the side view). The turbine pumping direction, however, always remains the same.

Each chain steamer was equipped with two of these water turbines, which were located on the port and starboard sides . During a turning maneuver, the water radiated forward on one side and backward on the opposite side, thus causing the ship to turn.

Paddle wheel and screw drive

Due to the strong current of the Danube, the chain boats could not go down here on the chain. If the chain tug was forced to suddenly stop (for example due to a broken chain), there was a high risk that the ships in the rear would run into the ships in front, leading to an accident . They therefore had large lateral paddle wheels as an additional drive for the descent , which were driven by steam engines with an output of up to 300-400 hp.

The third type of additional drive is the screw drive . This type of additional drive was partly used on the Danube for descent in order to enable towing operations in this direction as well.

literature

- Sigbert Zesewitz, Helmut Düntzsch, Theodor Grötschel: Chain shipping. VEB Verlag Technik, Berlin 1987, ISBN 3-341-00282-0 .

- Chain towing . In: Otto Lueger: Lexicon of the entire technology and its auxiliary sciences. Volume 5, 2nd completely reworked. Ed., Deutsche Verlagsanstalt: Stuttgart and Leipzig 1907, pp. 460–462 ( zeno.org ).

- Georg Schanz: “Studies on the bay. Wasserstraßen Volume 1, Die Kettenschleppschiffahrt auf dem Main “, CC Buchner Verlag, Bamberg 1893 ( digitized text from the library of the seminar for economic and social history at the University of Cologne ).

- Theodor Grötschel and Helmut Düntzsch: Equipment directory of the KETTE - German Elbe Shipping Society . In: Ewald Bellingrath : A life for shipping , publications of the association for the promotion of the Lauenburger Elbschiffahrtsmuseum e. V., Volume 4, Lauenburg 2003.

- Carl Victor Suppán: Waterways and Inland Shipping . A. Troschel: Berlin-Grunewald 1902, section: Steam shipping . ( Ketten- und Seilauer. P. 261/262, Tauereibetrieb. Pp. 262–265, Taking up and removing the chain. P. 265, Chain roll with finger cots. P. 266, Electric chain roll . P. 266, advantages and disadvantages der Tauerei. pp. 266–269, experiments using an endless chain. pp. 269/270; Textarchiv - Internet Archive ).

Web links

- Video of an electric track tractor driving through the Riqueval tunnel , accessed on November 15, 2010

- Forum with many old recordings of chain trucks from France (French), accessed on July 12, 2013

Individual evidence

- ↑ a b Peter Haas: About rope and chain shipping. (PDF; 5.9 MB) Schifferverein Beuel, archived from the original on September 23, 2012 ; Retrieved on January 17, 2016 (Source: Willi Zimmerman, Contributions to Rheinkunde 1979, Rheinmuseum Koblenz).

- ↑ Eduard Weiß: “The chain tugs of the royal Bavarian chain towing trade on the upper Main” in the magazine of the Association of German Engineers, Volume 45, 1901, No. 17, pp. 578-584

- ↑ Theodor Grötschel and Helmut Düntzsch: List of operating resources of the KETTE - German Elbe Shipping Society

- ↑ a b c Zeitschrift für Bauwesen Volume 16, Berlin 1864, p. 300, Verein für Eisenbahnkunde zu Berlin, minutes of November 10, 1863 ( digitized version )

- ↑ a b c Otto Berninger: The chain shipping on the Main. In: Bulletin. No. 6 of April 1987, Mainschiffahrtsnachrichten of the Association for the Promotion of the Shipping and Shipbuilding Museum Wörth am Main.

- ^ Architects' Association in Berlin: Deutsche Bauzeitung, Volume 2, Verlag Carl Beelitz, 1868, p. 100, ( Google Books ), (description of the 1st German chain ship between Neustadt and Buckau)

- ↑ a b c C. Busley: Aspirations and successes in shipbuilding . tape XXXIX . Journal of the German Engineers Publishing House, 1895, p. 704/705 .

- ^ A b c Otto Lueger: Lexicon of the entire technology. Retrieved November 11, 2009 (2nd edition 1904–1920).

- ↑ a b A. Schromm: chain shipping and electricity. In: Journal for electrical engineering. Year 13, Vienna 1895, pp. 264–266, ( Textarchiv - Internet Archive ).

- ↑ The pulling and moving of ships on canals, canalised rivers and free-flowing streams. Inland Shipping Congress in the Hague in 1894. In: Alfred Weber Ritter von Ebenhof: Construction, operation and management of natural and artificial waterways at the international inland shipping congresses in the years 1885 to 1894. Publishing house of the KK Ministry of the Interior, Vienna 1895, p 312-327.

- ↑ a b Sigbert Zesewitz, Helmut Düntzsch, Theodor Grötschel: chain shipping. VEB Verlag Technik, Berlin 1987, ISBN 3-341-00282-0 .

- ↑ a b Georg Schanz: Studies on the bay. Waterways. Volume 1: The chain towing on the Main. CC Buchner Verlag, Bamberg 1893, pp. 1–7 - ( digitized form ) from Digitalis, Library for Economic and Social History Cologne, accessed on October 29, 2009.

- ↑ Carl Victor Suppan: waterways and inland waterway . A. Troschel: Berlin-Grunewald 1902 advantages and disadvantages of rope work . Pp. 266–269 ( Textarchiv - Internet Archive ).