Federsee

| Federsee | ||

|---|---|---|

|

||

| Federsee area near Bad Buchau, with 33 km² the largest moor in southwest Germany | ||

| Geographical location | Germany , Baden-Wuerttemberg | |

| Tributaries | Seekircher Oh | |

| Drain | Federseekanal ( Kanzach ) | |

| Places on the shore | Alleshausen , Bad Buchau , Moosburg , Oggelshausen , Seekirch , Tiefenbach | |

| Data | ||

| Coordinates | 48 ° 5 '2 " N , 9 ° 37' 49" E | |

|

|

||

| Altitude above sea level | 578.3 m | |

| surface | 1.39 km² | |

| length | 2.25 km | |

| width | 1.03 km | |

| volume | 1,100,000 m³ | |

| Maximum depth | 3.2 m | |

| Middle deep | 0.8 m | |

| PH value | 8.81 | |

| Catchment area | 35.4 km² | |

The Federsee near Bad Buchau in Upper Swabia ( Biberach district ) is the second largest lake in Baden-Württemberg with an area of 1.4 km² . It is located in the middle of the 33 km² largest contiguous moor area in southwest Germany and is with it the remainder of a once much larger, about 50 km² covering post-glacial lake. This complex of lake and moor today represents the core of the geological Federsee basin , which after renaturation measures, with its former shores and islands, is now of outstanding natural and cultural-historical importance.

Today's basin landscape is now primarily a model for the ecological restoration of a natural landscape that has already been largely destroyed, including its botanical and zoological habitats and the associated safeguarding and research of ancient cultural products that have existed since the mid-19th century after the lowering of the lake level and drainage the moors came to light. Some of the remains of the pile dwellings are part of the UNESCO World Heritage Site .

The Federsee and surrounding him in the central basin Moor / Ried are now square kilometers in an area of 23.76, protected ie more than two-thirds, the area also contributes as a natural and European bird sanctuary " Federseeried " the title of " European reserve " and was included by the European Union as part of the FFH area Federsee and Blinder See near Kanzach in its “ Natura 2000 ” network of protected areas .

Topography of the basin and neighboring communities

geography

The Federseer Ried as part of the Federsee Basin in Upper Swabia is a natural area of the main unit 040 Danube-Ablach-Platten in the northern Alpine foothills . In terms of the landscape type, it is a moor landscape (moor-rich cultural landscape). In the handbook of the natural spatial structure of Germany by Meynen / Schmithüsen (1953–1962) the area is referred to as natural spatial subunit 040.25 Federsee Basin .

topography

Based on the former boundaries of the moorland determined by Karlhans Göttlich 1970/1972, the basin has a funnel-shaped foothill to the northeast (measured from the edge of the lake) six kilometers long, initially three kilometers wide, and at the end very narrow (300 m), northwest an approximately five kilometer long, continuously narrow (approx. 300 m) spur, possibly old glacier inflow zones. To the west, the basin widens to a bay about one kilometer deep and three kilometers long to the north-south, through which the Kanzach also flows, which in 1808/09 was expanded into a west-east drainage channel with a weir to regulate the water level of the moor km flows into the Danube. The much more extensive southern Federsee Basin, with the former approximately two kilometers long and a maximum of 700 m wide beet-shaped island of Buchau on the west side, is much wider and topographically much less structured, and today also shows the least bog character. At an initial width of four kilometers, it ends after about seven kilometers in a corner, from which a small branch branching off to the west, about two kilometers long , leads to the Schussenquelle . The eastern bank was once relatively steep, so that most of the early settlements were concentrated on the flat western bank, richly indented by bays and peninsulas.

Localities

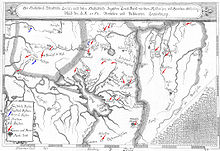

On the Federsee are Bad Buchau, Moosburg with Brackenhofen, Alleshausen , Seekirch , Tiefenbach and Oggelshausen . Also Kanzach , Allmannsweiler , Betzweiler and Dürnau be counted for Federsee area (they are part of communities of Bad Buchau). The adjacent illustration of the Federsee Basin from the early 20th century shows - at that time the lake area was 1.52 km² (1911) around 15% –20% larger than today - with the exception of the southern end, all neighboring communities and places in the vicinity . The light green areas surrounding the Federsee are consistently existing or former bog / reed (the term "reed" in southern Germany primarily refers to the surface vegetation of a bog , see Low German reed ). The villages and farmsteads ( in brackets behind each important prehistoric sites ) are either

- like Bad Buchau on a mineral island, i.e. not formed by peatland but by rock, which was previously connected to the land (district Kappel) by a plank dam,

- like Alleshausen, Seekirch, Kappel, Kanzach, Henauhof , Seelenhof, Vollochhof and Moosburg on partly peninsula-like land ledges formed by old and young moraines or

- like Oggelshausen, Ahlen and Tiefenbach on the same land edges, i.e. earlier shores of the then much larger lake.

- The places in the surrounding hills such as Uttenweiler or Bad Schussenried are on moraine soil.

In clockwise order these are starting at the top right:

- Northeast reed :. Ahlen (Ahwiesen), Alleshausen (Riedwiesen), Seekirch (Achwiesen). These and the stations Hartöschle, Ödenahlen, Stockwiesen, Grundwiesen, Floßwiesen, Innere Wiesen and Täschenwiesen are located on this long, funnel-shaped northeastern branch of the basin.

- Northwestern reed : Betzenweiler is located at the northern end of this very narrow spur .

- Central reed. with the Federsee in the middle: Tiefenbach , Oggelshausen , Bad Buchau (on the former island of the same name) are on the edge (clockwise ). Opposite the island on the former bank is Kappel with the stations Torwiesen and Bachwiesen between the two places on old moorland.

- Western reed :. Kanzach , Moosburg (on a mineral peninsula) and the Vollochhof and Seelenhofer Ried stations.

- Southern reed :. Is missing here except for its northern half with Buchau in the illustration. There are no larger towns there, but the early sites: Henauhof (on a mineral peninsula at the western end of the basin), plus Bad Schussenried with the Schussenquelle and the districts of Aichbühl and Reichenbach outside the southern end . The locations Riedschachen, Ödenbühl, Dullenried, Egelsee and Taubried (all except the first still in the area of the illustration) are also located in the southern basin; other former reed areas are the Oggelshauser, Wilde and Steinhauser Ried. Individual finds from different time zones between the Middle Neolithic and Hallstatt periods are documented for all of these locations . On the western heights of the southern basin, there are some Late Bronze and Early Iron Age sites, especially 15 Hallstatt-period graves and a cremation grave from the Middle Bronze Age urn field culture .

The people of the basin: origins and traditions

Spiritual background

In contrast to that of a natural landscape , the character of a cultural landscape is determined in different proportions by the people living there. In the Federsee area, where the archaeological finds are particularly meaningful and abundant, the interplay between culture and nature can be clearly followed in detail.

However, humans have been shaping the landscape on the Federsee since their time as hunters and gatherers , but especially since the so-called Neolithic Revolution and the invention of metal processing, even without such thought structures. The almost complete destruction of the landscape in the 19th and 20th centuries was followed by "landscape rescue" in the modern ecological sense. But it was inevitably also shaped by the landscape, initially by the floods, when the lake repeatedly overflowed its banks and destroyed entire cultures despite the ingenious pile-dwelling systems and wet-soil structures.

The name or the "Federsee" itself, which probably means nothing else than "moor, swamp lake", was found in earlier scientific publications by numerous scientists such as Leo Frobenius (Kulturgeschichte Afrikas, pp. 158-189) and Oswald Spengler ( Downfall of the West, pp. 131 f., 579 ff.) An appreciation. They examined the complex interrelationships that occurred primarily in prehistoric times. In Tomáš Sedláček's work , this can be found primarily from an economic point of view, for example in the “Economy of Good and Evil” (pp. 40 f., 47, 51 f., 56.). Today, paleoanthropologists and evolutionary biologists such as Jonathan Kingdon are mainly concerned with the subject of landscape formation by man ( And man created himself. P. 86 ff.).

Towards the end of the Stone Age , at the beginning of the Bronze Age , another fear emerged and led to increasingly more defensive buildings: the fear of other, strangers and their greed for predation. Because the societies gradually formed by the lake inhabitants had evidently already at the beginning of the third millennium in the end Neolithic street villages of the Seekirch type increasingly differentiated themselves socially and developed strata with increasingly wealthy elites, as can be seen from the equipment and arrangement of the buildings . Desires from outside were directed towards their riches. The fear of robbery and assault and the fear of the moor and the lake were tried in the early Bronze Age not only through massive palisades made of 15,000 pine poles plus additional wooden walls, but also through To meet offerings, as they are attested in depot finds, even through human sacrifices , as evidenced by the skull finds at the Wasserburg Buchau (six skulls in total in one depot), they may have been practiced at the Federsee, as elsewhere. And here now, in one of the legends , the lake also strikes back, defends or avenges the people in its sphere of influence and directs its force of nature against the attackers.

Historical-ethnic background

In the Neolithic, Upper Swabia and the Federsee region were already in the area of tension between north-south and east-west influences, and in this area the essential hiking and trade routes that connected these zones crossed. It is therefore not surprising that even at Federsee over the millennia many cultural groups and ethnicities have lived and left their mark on the various ur- and prehistoric Neolithic cultures and Bronze Age groups over Celts , Germans - especially Alemanni - and Romans up to the Franconian Merovingians and the Carolingians , with whom the real story begins here. (For a more detailed table and chronological breakdown of the individual cultural groups, see below .)

The later medieval and modern history of Upper Swabia , in which the Federsee region is embedded, also shows, because of the particularly pronounced cultural and power-political overlaps (Württemberg, Baden, Hohenzollern, Thurn and Taxis , Austria- Habsburg , Lorraine , Bavaria, Salier , Staufer , Welfen , Old Confederation , Holy Roman Empire ) a great variety, partly as spiritual domains of monasteries, partly as an imperial city like Bad Buchau and other small-scale secular rulers ( bailiffs , etc.) , partly as part of the Duchy of Swabia and later political units that emerged from it. All of these have left their mark not only in the formation of nature and landscape or in the testimonies and buildings unearthed by archeology or in the regional customs examined by folklore , but here and there also in language and folk memory.

The first of these traces are the various place and landscape names, here especially that of the Federsee itself; the second, even more nebulous, is hidden in legends that are centuries, sometimes even millennia. Because, according to Gero von Wilpert, " the legend is not only an important cultural-historical document (ancient ideas of community, feeling for nature), but also poetry as a way of dealing with the environment."

Names and Etymologies

Place names in the broadest sense, including place names , water names , etc., preserve old historical and natural conditions, which today mostly no longer exist and therefore for the past an area and the people living in them, often of high local historical significance because it beyond additional sources of information of archeology and science can deliver.

Preliminary remark: As with all etymologies, it must be noted here that there are sometimes several seemingly plausible ways of deriving a word from the linguistic history and that the first evidence mostly comes from Middle High German , sometimes also from Old High German , but that they often contain older language states, especially Celtic can be preserved. A direct derivation of the meaning from the current state of language is also tricky and often leads to so-called folk etymology . In addition, it often makes sense to use similar or the same place names from other areas for comparative purposes, with all due caution, especially when it comes to dialect geography .

There are several theories about the origin of the name "Federsee" , which also appears in Latin texts as Lacus plumarius - probably a learned Latinizing new formation from a "Feder-See" which is already misunderstood in terms of the origin of the word - there are several theories, four more folk etymological (No. 1– 4) and a linguistic-etymological (No. 5):

- Seen from above, the shape of the lake resembles that of a spring. To do this, one would have to have seen the lake from the air when the name was created, because this similarity is particularly noticeable in aerial photographs. In addition, before it was felled, the lake was nowhere near as feathery and rather irregular, looked a bit like a blob on old illustrations and changed its shape again and again.

- Because of the great number of birds that are and always have been here. This was and still applies to many such bodies of water.

- Closely related to this, the fact that one sees a large number of feathers floating on its surface is also discussed as eponymous, but only when one has overcome the wide reed belt.

- Analogous to the resilient ground, as it can still be experienced in the so-called "wobbly forest" near Bad Buchau, where the ground and the trees wobble "resiliently" when you stamp on it, because the trees stand on the vibrating moorland, originated from the siltation of the Ice Age Federsee. In the past, large areas around the Federsee must have shown this phenomenon, which occurs in a similar way in many moor areas.

- Most likely, however, is the linguistic explanation. According to this, the name comes from the Celtic word pheder , which means " marshland , swamp, moor". The name therefore refers to the origin of the lake itself and that of the surrounding landscape. In southern Germany in particular, old Celtic water names such as Rhine, Main, Danube or Neckar are very common. Even the Federbach, which used to be known as “Federach”, but which cannot be confused with the “Aach” flowing in from the north and which no longer exists today, should follow this pattern. For further interpretations see source below.

The different place and field names (those where important prehistoric finds have been made or settlements have existed) often clearly indicate the "damp" nature of the place:

- In this sense, "watery" name components are very common . like:

- Au (also in Henau) to ahd. ouwa. = "Land by the water"; Ah or oh , which go back to a common Germanic root * agwijō or ahwō (from it ahd. Aha-, cf. Latin aqua ), which means something like "belonging to water, flowing water" and in numerous Indo-European languages , including occur in Germanic and Celtic . Sometimes -aha has coincided with the ahd. - ahi (from -ahja ), which can mean "place, place with many things".

- Allen, Ahlen are historically associated with river names with the root al- , which are spread over a large part of Europe (Aller, Ill, Illmenau etc.) and, according to the Indo-European Hans Krahe , have an Indo-European root * el - / * ol- go back with the meaning "flow". The place "Ahlen" is documented as "Achelum" for 1120.

- Taub in "Taubried" probably goes back to an old Celtic word dubr for water (see Tauber ).

- The first part of the word "Kanzach" is unclear, the oldest evidence is "canca" with an unclear meaning (possibly after a gender name of the so-called "Bach knights" who temporarily lived there and are often referred to as "von Canza" in documents) apparently popular etymology a -Oh was attached as a water body or place name. The name may also come from a Celtic- Gallic “Kanto” (cf. Latin cantus , a word borrowed from the Celtic, Dutch cant , Upper German kanz ), which means “edge, corner, edge”. The name could therefore be related to the reed and moraine edge along which the river flows.

- "Schussen" -ried, which is mentioned in 1153 mhd. As shuozenried and around 700 as suzzenried , could either go back to mhd. Shuz = damming up of water or to mhd. Suzen = to rush. Since the Schussen south of Schussenried breaks through the moraine walls of the so-called "Singener Stadiums " and falls about 85 meters over a length of around nine kilometers in the so-called Schussen tobel , the second explanation is probably the most likely, but perhaps both have flowed into each other . The Celtic name of the river is “Sora”, which means something like “Sulzfluss” (ie a body of water that arises from “brawn-like” bog holes, a further development from this root is conceivable, possibly with a possible coincidence of meaning with the previous root ),

- "Floß", ahd. Flōz , in "Floßwiesen" stands for "flow, river", ie the "floating", "wet". - Common general or special nature and landscape names as parts of the name around the Federsee, which also indicate rather humid areas, are Ried, Moor, Moos, Bach, See, Graben, Bruch / bruck (marshland).

- "Reichenbach" is attested as Rinchinbah for 839 , in the sense of "rich in fish, water". Since there are Alemannic row graves here, the foundation of the village probably goes back to a corresponding manor house.

- "Dulle" in Dullenried may refer to the meaning "ditch" as in southern German. "Dole" back (cf. ahd. Tulli ).

- It is uncertain whether “barren” in “Ödenahlen” has the meaning of “empty”. However, it has this meaning as a word component of numerous field and place names (especially in Öd (en) hof).

- Öschle in "Hartöschle" refers to a high-altitude piece of land in a wetland. Hart refers to a wooded area (cf. Spessart, Harz).

- "Riedschachen": schachen goes back to ahd. Scahho , mhd. Schache , from this still nhd. Schachen for "piece of forest" (peripheral, archaic vocabulary). - Other natural names are:

- "Wiesen, Buch-" ( the most common tree species in the area since the end of the Neolithic );

- "Bühl" for hill / mountain ridge, so in "Aichbühl" = oaks on hill (since numerous places have the name part "Aich" and often also oak branches etc. in the coat of arms, this interpretation is certainly most likely);

- "Stock" - in Stockwiesen probably goes back to ahd. Stoc (h) (tree stump), refers to stagnation and is an old clearing name . A relation to “stagnate” in the sense of “still water” is rather less likely. Stockach and Stöckach are common place names, sometimes there is a coat of arms with a branch. -

Proper names : Often before -weiler, -hausen, -bach .

- You can find yourself in “Uttenweiler”, which goes back either to a settler named “Uto” or to a Blessed Uta . There are several places with Utten in southern Germany, Austria and Switzerland . In Uttenheim (Gais), for example, Utten goes back to the Bavarian name “Uota”. Such a "Uota" is historically attested as a member of the old Bavarian ruling house of the Agilolfinger .

- Other place names could also have their origins in old local aristocratic names, so presumably Tiefenbach , which was mentioned in a document as Tiuffenbach as early as 1277 in connection with a family of local aristocrats, although it cannot be proven, and then in 1353 when the place was first mentioned as Tuffenbach , thus possibly has nothing to do with a “deep brook” (although mhd. tiuf / deep means “deep”).

- Betzenweiler , Dürnau and Allmannsweiler also went through similarly complex language developments ;

- - "Allmannsweiler" is mentioned for the first time in 1268 as "Albinswil" ("Weiler des Albin", probably an Alemannic settler).

- - "Dürnau" may have something to do with the old Staufer noble family of the Dürn or it has a corresponding reference to thorns, since the place has a thorn branch in the coat of arms and is first mentioned in 1171 as "Dornon".

- - “Betzenweiler” first appeared in 817 as “Perahtramnilvillare” owned by the St. Gallen monastery. (The meaning is unclear.) It is attested in 1249 as "Bencewiller". This name is believed to be related to an original settler named "Benzo" from the 9th century. -

Buildings and places :

- "Weiler, Hausen, Hof, Kirch, Kappel" (chapel), "Gate, castle, church (s)".

- The " Seelenhof " and then the "Seelenhofer Ried" are probably related to an old Carolingian path chapel that stands here.

- Seekirch is probably a Merovingian foundation and is attested in 1254 as "Sekilche". A church already stood there at the time of Charles the Elder. Size -

The following are relatively unclear :

- “Oggelshausen”, especially since there is also an Oggelsbeuren belonging to Attenhausen , which occasionally also appears as Oberspeiren . In addition, there was once a castle near Oggelshausen . If the place that arose in the early medieval expansion period does not go back to an Alemanni Ogolt who settled here with his clan in the 7th and 8th centuries , there is also an iconographic interpretation. Since the coat of arms shows a courting (capercaillie) rooster (mhd. Orrehan ) on a branch, a Swabian-Alemannic “Gockel, Gockler” or “Jäckel” (jay) could have been the godfather here. The gurgling, rumbling courtship song of the capercaillie, which found a preferred habitat in the Upper Swabian hill country and its sparse forests and was a coveted game due to its size (up to 0.9 m), may have had an onomatopoeic effect here. (The word "Gockel" was also created in this way, see English cock , French coq , etc.).

- “Täschenwiesen” (to Tesche = bag?) Is completely unclear . Possible old meaning also "inside". (In fact, the place is located on the west bank of the northeastern Ried foothills in a strong, peninsula-like bulge.)

- "Alleshausen": Whether there is a reference to water is doubtful because of the connection with -hausen , which, like -weiler, often follows a proper name . The place name attested as Aleshusin in 1150 therefore possibly goes back to an early settler of this name, possibly also to "nobility" as in "Albert" etc. The place is first mentioned in 1150 as Aleshusin , 1254 it is called Alashusen .

- "Attenhausen": The Atten - in the name could have its origin in a personal name Ato as in Attenhausen (Krumbach) . A nearby Attenweiler is mentioned in 1254 as the seat of local nobility. The lords of Atinwilare are recorded from 1254 to 1296. A reduction from Hatten - as in comparable place names - is also conceivable. - "Henauhof": The meaning of the first part of the word Hen (n) (there is also the spelling with double) is uncertain. "Henn (en) -Au"? (to mhd. henne , ahd. henna ). More likely, however, is the derivation from the Celtic kewen = mountain hump, because in the “Description of the Riedlingen District Office” from 1827 it says: “The farm is on a hill that rises like an island from the moor and swamp grounds of the flat area , and was formerly probably also surrounded by the Federsee. It was probably one of the oldest possessions of the monastery. S. Kappel. “See also the analogous derivation by Hegau . - "Egelsee": The name of numerous lakes and places. “Leeches”, which prefer to live in still waters and wetlands, are conceivable as namesake. A further derivation takes "Ecksee" as the origin. A third, though very questionable theory assumes the origin in the Celtic, where it could have related to the sacred function as entrances to the Celtic otherworld , often located at the bottom of lakes : possibly Celt. agios , Greek hagios = holy. - Whether loch in “Vollochhof” (also “Vochenloch”) corresponds to the analogous endings -loch (ahd. Lōh ) as in “Schwärzloch, Degerloch” etc., which mean “grove, loose forest, scrubland” is uncertain. (In terms of language, a dative “vorm”, ie “Hof vor dem Wald” or “Hof vom Wald” (with assimilation rm → l) would also be possible. There is also an Obervolloch (also called Altvolloch) and an Untervolloch, where the mill goes from Obervolloch was relocated after the lake fell.). An assimilation k → l from “Volk-” (ahd. Folc ) to “Voll” - (cf. Volkmar → Vollmar) is also conceivable but not very likely. - "Brackenhofen": -brack stands either from the Greek brágos "flood plain" and brochē "rain, flood" as in "brackish water" or from nhd. "Fallow" (uncultivated land), which ends with kymrisch (celt.) * Mrag- no- is related and has roughly the meaning “decaying land”.

Myths and legends

One can roughly distinguish between four groups according to the topic:

- Legends that relate to prehistoric and early historical memories,

- Legends related to the magical and eerie environment of the moor and its metaphysical aspects,

- Legends with a Christian legendary background,

- Legends and fairy tales that revolve around general customs .

The first group is by far the most interesting here, because, as in many places that seem so mysterious, there are legends at Federsee , where old traditions shimmer out here and there, which could point to the former pile dwelling inhabitants, even if they are Christian in color.

The legend of the city in the lake is representative of this . It tells in several versions how there was once a city where the Federsee is now. In one version, the inhabitants led an ungodly way of life and the city is going under. In bright weather and when the water level is low you can still see the top of the church sticking out of the water. Others wanted to hear the bell too. In this lake there is also an island that is used to raise people; one then says: “This and that happened on the island of Bibbî in Federasai, and the tenth man does not see them!” It is supposed to be funny, as it was before in the lost city. This legend is possibly an old memory of the so-called “ Wasserburg Buchau ”, which was then transformed into a kind of “Atlantis”, yes to the “Swabian Troy” , mainly by the NS prehistoric historian Hans Reinerth during the Nazi era on the basis of this legend. was hyped up. If one interprets the myth, however, not in the ideologically motivated Reinerthian sense, but as an archetypal human memory pattern, for example after Carl Gustav Jung , Joseph Campbell and Claude Lévi-Strauss , then there is perhaps a memory of settlements devoured by lake transgressions, namely on Most likely to the last Bronze Age settlement, the Buchau moated castle , which, according to the findings of the rich rinsing areas, was possibly abandoned in the middle of the 9th century BC during the particularly dramatic Transgression T9, after which the residents withdrew to the existing island settlement, at the same time the end of all prehistoric wetland settlements in general and thus such an important event that it should have left deep marks in the memory of the local population.

In another version, the saga also tells how a solid city once stood in the Federsee. It had seven towers and high walls, and its inhabitants were not sinful, as in the first version, but good Christians who had built a little church on their island in honor of God. Over the years, their wealth grew, and since they did no harm to anyone, they had no enemies. One day many barges appeared on the Federsee, and the islanders realized with horror that an enemy war band was approaching their island. They were pagans whose bloody deeds had often been heard with horror. The fight was intense. The peaceful islanders succumbed to the pagan strangers who reveled and drank between the burning ruins of the conquered city until late at night. The winners alone have to pay for their bloodshed with their lives. When the drunken heathen lay in a deep sleep, the island began to sink, and the next morning the few refugees who had been rescued from the bank saw only the top of the church tower sticking out of the water. Since then the sunken city has been sleeping in the moors, and only the select can at certain hours hear the roosters crows and the dogs bark deep down below.

In both cases, collective memories of the catastrophic floods, which are not uncommon at the Federsee, as well as enemy raids on the two large settlements of the Bronze Age, the "Forschner Settlement" and the "Wasserburg Buchau", may have played a role, especially since the area too after its end it was never completely deserted, but, as stray finds and small settlements show, it was regularly visited and continuously had a relatively well-populated area up to the Celtic Heuneburg, only ten kilometers from the Federsee, and later Celtic villages, Roman manors and Alemannic as well as Merovingian Manor houses, so that there should have been a continuity of local memory.

The second group is represented here by the Federsee version of the saga vom Nebelmännle , a saga that is widespread throughout southern Germany and especially around Lake Constance . In her narrative center she has the ghostly dangerous, fog-swept, magical of the area, above all the fundamental conflict between the real world and the unreal, magical one.

Among the more Christian-motivated sagas and legends of the third group, those who spin around Adelindis von Buchau , the founder of the Buchau monastery and her husband and who are still alive today in the customs of Bad Buchau, should be mentioned here. (for more examples see below)

The fourth group , finally, the climbs are mainly local and mostly rural customs, often fluctuating way , like in the narrative structure to those in other parts of the country and specific Federsee-lowest, at best through the typical environmental features.

Limnology, geology, landforms

Topographic Limnology

The Federsee Basin is a typical groundwater-fed moorland, the water level of which remains relatively constant, unless natural or artificial runoff ensures drainage. The lake has only a small water catchment area , including the moor, about 70 km² . The tributaries are insignificant. The Seekircher Aach is the main tributary, and there is also a small stream flowing from the northeastern hills, the Tiefenbach, which flows into the lake at the place of the same name, which is the closest to the lake, and the Mühlbach near Bad Buchau. However, all of these streams were previously included in drainage measures and are now gradually being renatured.

The water level of the lake, which is regulated today and is between 60 cm and 2.80 m deep (originally more than 6 m), was probably primarily dependent on precipitation and the growth of the moor in the shallow outflow threshold through which the Kanzach today at the western end of the lake basin through an artificially created outflow regulated by a weir, so that the Federsee originally only had the Federbach as an outflow, with the exception of the Kanzachbach that left the basin at the Vollochhof via a low drainage threshold. In its current, dead straight course, the Kanzach was only moved and canalized here in 1808/1809 by being expanded into a west-east drainage channel with a weir to regulate the water level of the moor and, after several other streams, after about 20 km as a small river into the Danube flows out.

The Federsee is located on the main European watershed and drains both to the northwest into the Kanzach, whose narrow valley that runs through the hills connects to the Upper Danube, and to the southeast via the canalized Federbach towards the Rissal . There is an underground runoff via the Schussen spring, located on the southern edge a little outside the Federsee basin, to Lake Constance and thus into the Rhine system .

Geology and landforms

Geology of the mineral basin: See “Sea history” below.

Bog geology of the basin: The large glacial basin is lined with clay , which gradually changes into clay mud in the younger layers and is covered by limestone liver mud . From the late glacial period onwards , Lebermudde was deposited, a highly gelatinous and thus elastic fine sediment that leveled the unevenness of the glacial ground and reached great thicknesses. On this basis, extensive fens formed in the shallow bays of the northern, western and southern reeds , which quickly turned into transitional moors . In the southern reed a raised bog shield was created from the middle subboreal onwards . The silting processes, disturbed by numerous floods, led to a stratification that was differentiated over a small area, often interrupted by geological gaps in the stratum, so that at no point in the bog, not even in the center, is a complete sequence to be found.

Geology of the surrounding area: The surrounding heights of the Danube-Ablach-Platten are formed by a gently undulating old moraine flat hill landscape , which consists of a balanced mosaic of ground moraine , terminal moraine and gravel areas in former meltwater channels . In the south, which pushes in the front region young moraine , which belongs to it Sander to the lake and forms here a flat gravel plain which runs east to Rißtal. To the south of the huge terminal moraine stretches a typical young moraine landscape that has not yet been leveled and forms a small mosaic of hills, small lakes and wetlands. (For palaeogeology and paleolimnology, see “History of the lake” below.)

Landforms of the basin: In addition to moraine soils and gravel areas at the edge (see geology), there are several forms typical for old and existing bog areas (these are not marshlands , which do not develop peat):

- Wet meadows : Wet meadows are ecologically very valuable habitats for many marsh birds. The curlew , snipe , lapwing and meadow pipit can often be seen here. For all of these animals, rest is particularly important.

- Litter meadows : Litter meadows are fens. They get their name from the mowing , which was used as litter for the stable in agriculture. The moist meadows that emerged on the exposed former lake floor after the felling of the lake were neither suitable for arable farming nor for hay extraction. The growth consists mainly of sour grasses , is low in protein and sharp-edged. Litter meadows cover a wide area of the nature reserve. They are the most species-rich habitat for the animal world here, because since they were mowed very late, the meadow breeders could raise their young, orchids were able to bloom and seed them. The litter meadows have meanwhile been given up by agriculture because of their low economic benefit and are now maintained by nature conservation. However, you now threaten the natural progression to overgrown with bushes , which would entail the disappearance of the animals in the open space.

- Fen : The very nutrient-rich fen extends further towards the lake. The typical vegetation consists of mostly dense and tall vegetation, which largely displaces light-loving mosses. The most important vegetation units are alder forests , reed beds and large sedge beds . Unlike the litter meadows, the fen lies at the level of the groundwater level. The fen belongs to the silting zone and is not particularly rich in animal and plant species. A typical representative of the vegetation is the marsh marigold that can be seen in spring .

-

Transitional bog : A wide belt of reeds is typical for the transition bog (approx. 250 hectares in total). The closed reed belt is one of the most important habitats in Baden-Württemberg for species adapted to reed. The reeds provide food, breeding opportunities, hiding places and also sheltered sleeping places. Where the reeds find optimal conditions, they are very dense and high (up to 4 m). In doing so, it displaces other plants. The old stalks die in autumn, but they only collapse after a few years.

The reeds have a decisive influence on the appearance of the Federsee. The transitional moor offers a natural and good habitat for breeding birds in particular. Especially due to the undisturbed reed zone, endangered bird species are still at home there. One such species is the great bittern . As impressive as this reed belt is, on the other hand it also illustrates the tragedy of this lake. The lake is increasingly silting up. The reeds play a not insignificant role in this silting-up process, as they provide the constant "silting food". - Rain bog: This wet zone, also known as a raised bog, has disappeared except for a small remnant, 23 hectares in the “Wild Ried”, because it has been peated. Rain bogs are peat deposits without contact with mineral groundwater. Water and nutrients are determined exclusively by precipitation. Small peat lakes often form at their edges, which can then also have contact with the groundwater, or so-called peat ponds , where this is not the case. The former Egelsee in the southern basin may have been such a body of water fed exclusively from the moor.

- The moor forest : It is a special form that was artificially created when the ban area Staudacher, around 1900 an open reed meadow landscape, was bought by NABU in 1911 for nature conservation and research purposes and thus removed from any human influence. Today there is a pronounced moor forest that serves exclusively as a retreat for animals and plants and is not cultivated. Sick trees and dead wood remain in the forest. Wood decomposers make the nutrients available again. The nutrient cycle remains intact. Here you can observe an extraordinary diversity of species and structures: There is a rich layer of herbs and shrubs, above it trees of different species and different ages. Typical woods are downy birch, buckthorn and creeping willow, as well as spruce, pine and gray willow, but also the bush birch that has grown here since the Ice Age .

In terms of birds, robins , warblers and other songbirds find food, hiding places and breeding places here. Countless wood-eating insect larvae live in rotten trunks and feed the great spotted and small woodpecker . Tits , nuthatches , owls , stock doves , dormice , wild bees and bats live in abandoned woodpecker caves . The moor forest therefore forms an extraordinarily closely interlinked biotope that could only develop again because human influence is strictly prohibited.

Flora and fauna

As a typical flat lake, the Federsee is a habitat for many species adapted to warm, nutrient-rich waters. Due to its shallow depth, sunlight reaches the ground, so that lush aquatic vegetation can develop. The banks are richly structured by bays and therefore sought-after breeding grounds for birds and fish. Thanks to the mosaic of diverse, closely interlinked habitats, a large number of animal and plant species find suitable conditions on the Federsee. (Species that live on or in the water or in moors or corresponding wetlands are mentioned here.)

plants

After the renaturation of the area with the extensification of agriculture in the late 20th century, the local flora is again as diverse and typical as in other moorland and reed areas and shows, apart from the areas used for agriculture and forestry, especially at the edges of the basin and in In the southern basin there is an extraordinarily broad and differentiated range of species of plants adapted to this type of landscape.

In detail there are:

- Over 700 higher plant species. - including ten orchids and some rare ice age relics - grow in the Federseemoor. The latter are mainly plants that have survived with us since the last ice age due to the special climate in the moor (partly the only location in the country), including: Karlszepter (June, July), creeping willow , bush birch (all year round) .

- On aquatic plants. In the now year-round clear water there are, among other things, spawning herbs , milfoil , horn leaf and waterweed , which offer the fish offspring protection and food. Rare plants such as the frog bite or the water hose also live here in the Federsee. The enormous algae bloom , based on massive over-fertilization , which had brought the Federsee to the edge of tipping over , has now been eliminated.

- Typical woods. are downy birch and pine, spruce, mountain ash , buckthorn and various types of willow , especially in the so-called moor forest (see above).

Animals

The large areas of flat and transitional moors with large stocks of reed beds, alluvial and riparian forests as well as wet and humid meadows are important habitats for species in need of protection nationwide. Animal species that live in or near the water or reed and / or feed on it and its flora and fauna are naturally typical. Especially in the southern basin, which shows only minor reed characteristics, there are also the "classic" forest and landscape animals (deer, foxes, hares, wild boars, etc.), with the exception of the natural Egelsee high moor and other nature reserves like the so-called Wackelwald near Bad Buchau.

The following stocks can be found:

- 16 species of fish live in the lake and in the trenches . Among them are some rare species. The largest and best-known species, the catfish , grows to over two meters in the Federsee and can weigh up to 50 kg. The Federsee is also known for its occurrence of the wild form of carp . Also significant is the occurrence of the mud whip , a rare loach species that lives in the trenches on the ground and is the most common location in the whole country. In addition to the blue-banded harlequin , which has only been documented for a few years , the following species of fish can be found in the Federsee and in the trenches: minnow , crucian carp , arbor , roach , rudd , tench , brook loach , mud whip, loach , catfish , eel , pike , perch and stickleback . The most common is the bream with a population of around one million specimens.

- Of amphibians and reptiles were detected: newts , toads , Toads , frogs , lizards , slow worms , grass snakes , vipers .

- As a European bird reserve, the Federsee offers a home to 268 bird species according to the latest counts (see below), including numerous, sometimes only passing and resting water birds such as swans , around ten different species of ducks , great crested grebes and coots , geese , cormorants and herons , but also Rare species such as bittern or goosander , plus the hen harrier as a representative of the birds of prey , because the Federsee is the most important wintering place for hen harriers in southern Central Europe (72 specimens of these rare birds were acutely detected in the Federseemoor in January 2012). At times, and especially during bird migration , several thousand water birds can be observed at the same time. While walking through the spell area Staudacher mixed Meis swarms fall of Coal, Blue, fir, swamp, beard and chickadees and nuthatches, tree creepers and Goldcrest on. In contrast, robins and wren hibernate as solitary animals in the undergrowth. White stork and bluethroat are also found.

- For bats. The insect-rich wet meadows also offer ideal hunting conditions, so that 12 of 25 German bat species have been identified here, including pipistrelle , water bat and great noctule bat .

- On larger wild animals. there are deer that are relatively numerous, as they are not allowed to be hunted all year round, and wild boars also live here. The usual spectrum of small game , such as red fox , polecat , and rodents such as water shrew , ground vole , squirrel, etc., have now found beavers again on the Mühlbach near Bad Buchau settled.

- The most noticeable insects are dragonflies with 40 species, including some very rare ones. There are also 70 species of day butterflies , e.g. B. Large meadow birds and 500 species of moths as well as hymenoptera such as wild bees , ants , hornets and wasps , as well as rare species of beetles and spiders , which also benefit from the diversity of insects, especially in the Staudacher forest .

Maritime history

Glacial period

Today's Federsee is the result of a post-glacial silting process that would lead to the lake's complete disappearance without human intervention. The formation of the Federsee goes back to the excavation by a rift ice age glacier tongue , which left a large over-deep basin, which is bordered in the west, north and east by ground and terminal moraines . The drainage to the south was cut off by the terminal moraine, so that an ice reservoir with about 30 km² and up to 40 meters deep was formed and the drainage was oriented towards the north towards the Danube. According to drill core findings , the original basin floor is around 144 m below the current moor surface. The area of the lake at that time is roughly identical to the maximum extent of the moor, of which a good 23 km² are under nature protection today.

By the Würm Ice Age , the basin was already largely filled with meltwater sediments (gravel, sand and clay) when it was sealed off by a young terminal moraine in the southeast between Bad Buchau and Bad Schussenried . The resulting ice rim reservoir was originally probably 30 times larger than today's remaining water surface. Strong westerly winds created a surf cliff up to ten meters high in the moraine walls on the east bank , which today appears as a prominent step between Oggelshausen and Seekirch .

Holocene

After the ice melted, the inflow from the south dried up in the Holocene , and the silting process began when the dead plants and algae sank to the bottom of the lake and slowly raised the lake floor. The siltation in the already heavily filled basin ran after the deposition of banded clay , sand and sea chalk over a nutrient-rich flat or low moor to a nutrient-poor upland moor shield , which reached a thickness of up to 2.5 m above ground level and on the east side into the The Federbach, which drains off into the middle of the basin, drained lake felling no longer in its natural course.

Silting processes: Today only little of this old raised bog is preserved in the southern part of the basin, although it originally formed a plain in the Bronze Age , which, with the exception of the last remains, has now been peated. The silting up of the shallow bays in the south began as early as the late glacial period and in the subboreal area extended into the zone of the central southern reed. (The early to mid-Bronze Age wetland settlement of Forschner emerged there later .) Climatic changes in the course of the Holocene with alternating dry and wet phases as well as cold spells repeatedly brought periodic flooding (transgressions: T) of the central body of water with them, so that the silting processes by no means continuous, but with several floods, during which the lake was able to recapture large areas of peat. Such transgressions occurred particularly in the Neolithic , and here especially in the Early Neolithic . Of the total of 10 counted lake transgressions in the Holocene, there were several with catastrophic consequences for the settlers and their villages up to the Iron Age Hallstatt period , such as those there due to the excellent conservation conditions for biological materials (especially timber, which can sometimes be dendrochronologically precisely dated are) show abundant archaeological finds in the bog. A total of six major floods were counted that had a significant impact on Neolithic settlement activity (figures from approximate BC, beginning of transgression in each case, rounded): T4 4300, T5 3900, T6 3700, T7 2500, T8 1500 and T9 800. T1– T3 (7000, 6500 and 6300) occurred before the settlement phase at Federsee; T10 took place around the turn of the times, when the basin was very sparsely populated, if at all. In between there were several smaller floods, the last one shortly after 500 AD.

Modern times

Until the middle of the 18th century

In modern times , from the Late Bronze Age until about 200 years ago , the lake still had an area of about ten square kilometers and extended to the surrounding villages, including Kappel, Brackenhofen, Alleshausen, Seekirch, Tiefenbach. Oggelshausen and the Free Imperial City of Bad Buchau, including the monastery , surrounded the lake, in the south of which a mysteriously inhospitable moorland stretched as far as Sattenbeuren and Steinhausen. It was a primeval landscape that separated the lake in large parts from the solid shore, wild and impassable and left to its own devices for a long time. It was only two centuries ago that humans discovered the value of the moor as an economic factor and intervened with the aim of extracting land and peat .

For centuries there had been disputes between the wealthy Buchau women's monastery and the independent, but restricted city of Buchau. It was mostly about the use of the wet meadows, grazing rights and peat cutting. In order to gain new land, the Reich Chamber of Commerce that was called upon to finally decide to lower the Federsee.

The fellings

The first felling of the lake began gradually by the Schussenried Premonstratensian monks, because the water-saturated high moor of the "Wild Ried" posed a danger that should not be underestimated for the residents. Especially in spring, the moisture caught in the peat often poured over the fields like a torrent cause considerable damage. From 1765, therefore, the regulation began by dug drainage ditches and thus also gained new areas for cultivation. The lake area was then reduced to seven square kilometers from 1787/88 further from the north by deepening and channeling the western Kanzach river , which corresponded to a lowering of the water level by 85 cm. This felling resulted in 415 hectares of virgin land.

Since the result was not satisfactory, a second lake felling was carried out in 1808/1809 on the orders of King Friedrich von Württemberg , who was now responsible after the secularization of 1802 , which reduced the lake area by 114 cm to only 2.5 km² and the depth reduced to 5.4 meters (today 1.3). The fact that the lake could not be lowered by three meters as planned was due to the constant flow of sand at the penetration to the Kanzach Canal. The reclaimed areas, where about 400 ha, however, were not very fertile, moist and could usually only for the recovery of bedding are used (so-called. Fen meadows ), so that they soon themselves left, followed by extensive reedbeds , Riede and wet forests developed.

The silting process with a sharp drop in the groundwater level then led to a further reduction in the area to 1.5 km² by 1911. Since then, it has been possible to improve this process through improvements in the use of agricultural fertilizers, through the extensification of cultivation and avoidance of heavy equipment in order to avoid further soil compaction, and in the sewage treatment technology it has been slowed down considerably. At present, attempts are even being made to regulate the Kanzach weir to raise the water level slightly.

Peat extraction and its consequences

Already before 1765 there was a mining of peat operated by the monastery for burning purposes, however on a small scale and only in the Steinhauser Ried, where it can be done with the so-called Wäsen-Stechen (i.e. the manual cutting of individual pieces of peat, the so-called "Wäsen") ) for heating purposes. In 1764 the first system of ditches was created there to facilitate mining. But it was only in the course of the new rural freedoms that a reed cooperative was founded in 1854 , which initiated the systematic extraction of fuel peat in the "Wild Ried". The Schussenried railway station was built as early as 1850 so that the peat could be removed more easily, and the planned drainage began.

The immense peat requirement of the Ulm – Friedrichshafen southern railway , which was mainly met in the Steinhauser Ried south of the “Wilder Ried” , then led to the final loss of the raised bog that had grown for thousands of years . The main trenches necessary for this were dug in 1859/1860 in advance of the large-scale peat exploitation together with the "State Peat Mastery". The reed was systematically drained. The State Peat Administration was established in 1874, mechanical peat extraction began in 1879, a peat factory was built in 1885, and peat exploitation was brought to an industrial level. This resulted in further large-scale drainage measures through main trenches.

In 1910 the state peat factory dug a new main trench, which led in a straight line from the "Inner Ried" towards Steinhausen and was deepened in 1925 to its current level of 2.5 m. As a result, the peat of the Steinhauser Ried was pushed to the lowest peat layers, a process which, together with numerous new intermediate ditches to lower the groundwater level across the board, led to the deterioration of the archaeological foundations previously protected in the wet in their biological material substance (wood, etc.) to destroy potential future finds. (In the meantime, measures to increase the groundwater level have been initiated.)

All of these measures for drainage and peat extraction had two consequences, one negative and one positive:

- The disappearance of the millennia-old natural landscape of the Federseemoor.

- The discovery of the globally unique prehistoric settlement sites, because it was only the peat extraction and the ever deeper drainage that led to the discovery and excavation of the sites previously hidden in the peat. However, the first rather improper excavations led to the destruction of some of these sites. Last but not least, the continual lowering of the groundwater level and the draining of large areas of bog, which led to the drying out and decay of the biological finds, which are only abundant in pile dwellings and wet-soil settlements like here, and the loss of which is therefore particularly serious for archeology , was also fatal . In fact, when the research was resumed at the end of the 1970s, some of the early excavation sites had to be laboriously localized again through measurements, inspections and probes , whereby the state of preservation of some old sites proved to be catastrophic, especially in the southern moor, which was particularly badly affected by peat extraction.

By 1950 the formerly rich peat deposits had been mined except for a 22 hectare remnant in the Wild Ried. Federseetorf was mined until the 1960s. Its use as bath peat, for which there is no medical substitute, played a rather minor role here. The exploitation as burning peat was much more serious. Peat grows back very slowly: about 1 mm per year.

Impending overturning and renaturation at the end of the 20th century

After the sewage discharge into the lake began in 1951, the water quality of the Federsee became an ever more pressing problem, above all due to the decomposition-related loss of oxygen and putrefaction under anaerobic conditions. Until 1981, the untreated wastewater from the lakeside communities ended up in the Federsee via the drainage ditches. The manure fertilization of the meadows supplied the lake with further nutrients via the ditches. In addition, the nutrients bound in it were also released during the decomposition of peat due to drainage. In the very nutrient-rich water, blue and green algae were able to multiply particularly strongly. They displaced the other aquatic plants, and with them many animals that lived on the plants also disappeared; the water bird population, for example, collapsed completely. The lake was greatly impoverished and threatened to tip over .

The first step in the rehabilitation and renaturation of the Federsee was in 1971 the installation of a weir in the Kanzach outlet, with which the water level could be regulated. In 1982 a sewage treatment plant with a 24 km long ring line around the lake was put into operation. Since then, no more untreated wastewater has entered the lake. He was visibly recovering. (For further details on the protective measures see below) The formerly native species returned more and more, because since 2006 the water quality has improved rapidly. Since 2008, the lake has been clear to the ground in summer and is now a healthy, self-regulating biotope again with numerous aquatic plant species that are so important for young fish and even freshwater mussels that are particularly sensitive to water pollution . The many fish in turn attracted the water birds in large flocks, whose food they produce in addition to the equally diverse insects that have returned. For the current status of the measures, see the detailed report by the State Institute for the Environment, Measurements and Nature Conservation Baden-Württemberg .

Today's use of the Federsee area

The modern use of the Federsee Basin is remarkably diverse, especially if one considers "use" not only from a purely economic, production-oriented aspect, but also considers the benefits for the general population in the area and especially outside it. In this sense, there are five different areas of use:

Economy

A direct economic use of the basin in the sense of agriculture is possible only to a limited extent due to the inadequate soil quality , despite the various drainage measures of the bog , especially in the 19th century, which, however, mainly served to remove peat and limit the constant flooding Apart from a few unsuccessful attempts at cultivation in the present, the Federsee's silting areas were never arable, so that mainly cattle farming is practiced here. The southern basin, on the other hand, is partially forested and is used for forestry with spruce forests . Arable farming is also possible there in dry areas.

The framing of the Federsee Basin, on the other hand, offers deep to medium-sized soils of moderate to good arable suitability, which are used today for both grassland and field farming . Around 220 farms are farmed around the Federsee. Approx. 1800 hectares of arable land and approx. 1400 hectares of grassland are cultivated. Around 1500 dairy cows, 3100 cattle and 5000 fattening and mother pigs are kept on the farms. Like almost the entire Upper Swabian hill country , the Federsee area, in contrast to the climate-favored Lake Constance basin, is only moderately to sufficiently suitable for fruit growing, because it is 578 to 650 m above sea level and has a moderately cool climate in a basin that is also exposed to cold air. The peat mining , which was economically important from the second half of the 19th century , has ceased as described above since the middle of the 20th century.

natural reserve

In the Federseemoor there are almost 3000 hectares of habitats worthy of protection across Europe, such as extensive fens, lime-rich swamps, regenerative raised bogs, transitional bogs and bog forests. It is also home to significant populations of particularly protected animal and plant species ( FFH species ). Fish species threatened with extinction such as mud whip and wolffish are among them, as well as the golden pied butterfly , the yellow-bellied toad and the peatweed orchid . One species of beetle has its only German occurrence here.

The protected areas are structured as follows:

| Protected area shares | % Total landscape area |

| FFH areas | 61.41 |

| European bird sanctuary " Fedeerseeried " | 64.14 |

| Nature reserves | 51.84 |

| Other protected areas | 0 |

| Effective proportion of the protected area | 64.47 |

Source: Federal Agency for Nature Conservation, as of 2010

-

Development and general measures: The Federsee is, with parts of the Federseer Ried, one of the oldest nature reserves (No. 4019) in Baden-Württemberg. The bog areas created by the felling of the lake with the Federsee in the center were placed under nature protection as early as 1936 (NSG Federsee 1400 ha). Other nature reserves in the Federsee basin, which were later designated, are: "Wildes Ried" (raised bog rest, 23 ha, 1966), "Riedschachen" (bog forest, 11 ha, 1941), "Südliches Federseeried" (Feuchtwiesen, 522 ha, 1994), "Westliches Federseeried" (241 ha, 1999) and "Nördliches Federseeried" (179 ha, 2001).

Due to the application submitted by ReHa Federseemoor by the Tübingen regional council for the renaturation of further parts of the Federseemoor, around 1.3 million euros are available from 2009. Half of the costs are borne by the European Union , the other half comes from the state of Baden-Württemberg , NABU Baden-Württemberg, the district of Biberach , Vermögens und Bau Baden-Württemberg (VBBW) and the Foundation for Nature Conservation Fund Baden-Württemberg (SNBW).

-

Bird protection: 107 of the 268 bird species are breeding bird species . A department of the Federseemuseum and a NABU center provide information about the importance and history of the moor . The Federsee area is a bird sanctuary according to the European Fauna-Flora-Habitat Directive and part of the European biotope network Natura 2000 . The Federsee is also an important resting place for migratory birds . Up to 70,000 starlings spend the night together in the reeds in spring and autumn before they move away. In addition, some interesting winter guests can be observed. In summer you can see common terns hunting at the lake . They were settled on brood rafts. Bearded tit , cane swirl and cane bunting breed in the reeds . Other characteristic breeding birds of the reed belt are the pond warbler and reed warbler as well as the water rail , which is revealed by its typical squeak. Every year 15–18 of the approximately 25 pairs of Marsh Harriers in Baden-Württemberg raise their young here. Meadow pipit , snipe and curlew can be observed in the adjoining wet meadows , and the field owl is primarily noticeable acoustically. With more than 200 breeding pairs, the Federseemoor is home to by far the largest population in the Württemberg population of the rare whinchat . In the near-natural moor forests, there is a colorful variety of songbirds, as well as gray and small woodpeckers . In winter, goosander , great crested grebes and various types of ducks can be observed from the Federseegeg , such as B. spoon , teal , knack , gadfly and golden bell . Storks have now been reintroduced.

Federseemuseum - reconstructed moor village. Archaeologically correct, it is a wetland settlement , not stilt houses .

Federseemuseum - reconstructed moor village. Archaeologically correct, it is a wetland settlement , not stilt houses .

Prehistoric archeology

Overview and meaning

The Federsee Basin is known as one of the most important archaeological find landscapes in Germany. The Federseemoor is even of international importance in prehistoric research. The Federseeried with the Restfedersee in the middle not only forms one of the largest contiguous moor areas in the south-west German Alpine foothills, but has also been considered the richest moor region in prehistoric wetland settlement and pile dwelling research north of the Alps since its first archaeological exploration in 1875 . More than 19 prehistoric settlement sites have now been found there. The large number of finds at the Federsee has meant that the course of the regional settlement history from the Late Paleolithic to the Iron Age can be retraced here with examples. The prehistoric archeology of the Federsee Basin brings to light year after year during the regular excavation campaigns of the State Monuments Office in Stuttgart new knowledge about the area's uniquely densely populated area and the local culture, especially during the late Neolithic and Bronze Age phases, over a period of around about 3800 years. During this period, the Federsee wetlands were sought out as settlement areas. However, this process was not a continuous one, but was a process that was massively interrupted by sometimes massive rises in lake levels, but also by severe cold spells. In the archaeological finds from all epochs, far-reaching cultural contacts in both the east-west and north-south directions (see the maps above) show that the stages of cultural development that can be identified in them cannot be classified as a special case of a peripheral small landscape. The Federsee, not far from the Upper Danube and on a traffic axis leading south to Lake Constance and further over the Alps, was rather integrated into the extensive cultural and historical events of Central Europe, taking up influences that penetrated along the Danube as well as those via the Alps the Mediterranean.

Since 2011, because of their excellent conservation conditions, but above all because of their "central importance for the universal cultural heritage of mankind", three of the Federsee settlement sites that have now been discovered and researched have been on the UNESCO World Heritage List (Forschner settlement, Alleshausen-Grundwiesen, Alleshausen / Seekirch-Ödenahlen). The Federseemuseum in Bad Buchau, which was founded at the beginning of the 20th century, provides information about the entire archaeological spectrum with its twelve Moordorf houses reconstructed in the outdoor area between 1998 and 2000 according to the most modern archaeological findings.

Chronology of the prehistoric cultural sequence of the Federsee Basin

(As of Schlichtherle, 2009 and 2011/12)

The times are all v. And relate locally to the Federsee, if cultures there are not detectable on southern Germany or central Europe. They are based locally on pollen findings, C14 ( radiocarbon dating : when you specify . Dat as a calibrated RC individual measurements), Thermolumineszenzdatierung and especially dendrochronology ( ". Dendrodat" "Dendro" or).

At localities only the most important are mentioned. The Roman numerals refer to the end of excavation different stations in the same district or hall or a Won . For more precise localization, see the location information in the following chapter including the illustration.

Abbreviations :

WKE = UNESCO World Heritage Site

> T = Transgression (main flooding phase , each approximate start)

|

Stone age

Paleolithic

Late / End Paleolithic

Mesolithic (Middle Stone Age)

Early to middle Mesolithic ( Holocene ): 8000 to approx. 5700 BC Chr.

> T1 approx. 6950 BC Chr.

End Mesolithic (up to 5400) with transition to the Old Neolithic (5400–5000)

Neolithic

Early Neolithic 5400 to 4400

A. Early Neolithic 5400 to 5000

B. Middle Neolithic 5000 to 4400

Late Neolithic 4400 to 2300

A. Early Neolithic 4400 to 3500

> T4 approx. 4300 BC Chr.

> T5 approx. 3900 BC Chr.

> T6 approx. 3700 BC Chr.

> T7 approx. 2700 BC Chr.

First big gap in settlement: End Neolithic to Early Bronze Age Metal time

Bronze age

From approx. 2300 to 800 BC With strong regional fluctuations

> T8 approx. 1500 BC Chr.

> T9 approx. 800 BC Chr. End of the actual Moor colonization (wet soil settlements). Settlements on mineral soils (islands, banks) persist in the Metal Age.

Iron Age From approx. 800 BC Chr.

The verifiable prehistoric settlement of the actual Federsee basin (Ried) ends afterwards; however, the basin rim area was evidently still sporadically populated until around 500/700 AD, with the transition to continuous settlements on the basin rim. However, the reed itself in the basin remained free of settlement. Historic time

Romans, Alemanni , Merovingians . From 700 AD in the area of Bad Buchau there is evidence of an Alemannic aristocratic court , seventy years later a nunnery. |

tourism

The Federsee area benefits above all from the two areas mentioned above, i.e. nature and bird protection ( Federsee European Reserve) and the prehistoric archaeological sites that are partially designated as UNESCO World Heritage . So-called soft tourism is the basic principle .

As there is almost no direct access to the open water through the reed and moor belt, there is the 1.5-kilometer Federseesteg in Bad Buchau, which leads from the parking lot of the Federseemuseum through the reeds to the open water, where there is an observation platform . In addition, a footbridge leads from the parking lot of the Federsee Museum through the ban area named after Walter Staudacher, a pioneer of Federsee archeology, to Moosburg . Tiefenbach is closest to the water . If the Federsee, which is only about two meters deep, is frozen in winter, you can walk from Tiefenbach to the Federseesteg in Bad Buchau. A cycling and hiking trail with a length of approx. 20 km leads around the Federsee.

The Federseebahn , the Federseemuseum and the NABU nature conservation center in Bad Buchau offer further possibilities. Since April 1, 2004 there is a new address for those interested in archeology: the new ArchäoPark Federsee , where the Federsee Museum Bad Buchau and the newly built Bach knights castle Kanzach show open-air scenarios from the Paleolithic to the late Middle Ages, including one complete and based on the latest archaeological findings reconstructed wetland settlement.

Another focus of the area is its climatic properties with numerous medical spa and rehabilitation facilities that also offer peat therapies. Bad Buchau is also a spa .

See also

Literature and Sources

- Thomas Bargatzky: cultural ecology. In: Hans Fischer (Ed.): Ethnology. Introduction and overview. 3. Edition. Dietrich Reimer Verlag, Berlin 1992, ISBN 3-496-00423-1 , pp. 383-406.

- Otto Beck: Art and history in the Biberach district. Jan Thorbecke Verlag, Sigmaringen 1983, ISBN 3-7995-3707-4 .

- Brockhaus encyclopedia in 24 volumes. 19th edition. F. A. Brockhaus, Mannheim 1994, ISBN 3-7653-1200-2 .

- Barry Cunliffe (ed.): Illustrated pre- and early history of Europe. Campus Verlag, Frankfurt am Main 1996, ISBN 3-593-35562-0 .

- Rüdiger German among others: In the heart of Upper Swabia. Bad Buchau and the Federsee. 2nd Edition. Federsee-Verlag, Bad Buchau 1988, ISBN 3-925171-13-4 .

- Hans Günzl: The Federsee nature reserve. Landesanstalt f. Environmental protection Baden-Württemberg, 1985, ISBN 3-88251-077-3 .

- Gerhard Haas, Hans Schwenkel : The Federsee nature reserve . (= Publications of the Württ. State Office for Nature Conservation and Landscape Management. Issue 18). 1949.

- Herder Lexicon of Biology . 8 volumes. Spektrum Akad. Verlag, Heidelberg 1994, ISBN 3-86025-156-2 .

- Emil Hoffmann: Lexicon of the Stone Age. Verlag C. H. Beck, Munich 1999, ISBN 3-406-42125-3 .

- Claus-Peter Hutter (eds.), Alois Kapfer, Werner Konold: Lake, ponds, ponds and other still waters. Recognize, define and protect biotopes. Weitbrecht Verlag, Stuttgart 1993, ISBN 3-522-72020-2 .

- Erwin Keefer (ed.): The search for the past. 120 years of archeology at the Federsee. Exhibition catalog. Württembergisches Landesmuseum Stuttgart, 1992, ISBN 3-929055-22-8 , p. 62.

- J. Kingdon: And man made himself. The risk of human evolution. Birkhäuser, Basel 1994, ISBN 3-7643-2982-3 .

- Wolf Kubach: buried, sunk, burned - sacrificial finds and cult sites. In: Bronze Age in Germany. (= Archeology in Germany. Special issue. 1994). Konrad Theiss Verlag, Stuttgart 1994, ISBN 3-8062-1110-8 , pp. 65-74.

- State Office for Monument Preservation Baden-Württemberg (Ed.): Unesco World Heritage: Prehistoric pile dwellings around the Alps in Baden-Württemberg. Text: Sabine Hagmann, Helmut Schlichtherle, State Office for Monument Preservation in the Stuttgart Regional Council, Hemmenhofen Office 2011.

- Hermann Müller-Karpe : Basics of early human history. Volume 2: 2nd millennium BC Chr. Theiss Verlag, Stuttgart 1998, ISBN 3-8062-1309-7 .

- Helmut Schlichtherle : The archaeological find landscape of the Federsee basin and the Forschner settlement. Settlement history, research history and conception of the new investigations. In: The Early and Middle Bronze Age "Researcher Settlement" in the Federseemoor. Findings and dendrochronology. (= Settlement archeology in the foothills of the Alps. XI; = research and research. Pre- and early history of Baden-Württemberg. 113). Konrad Theiss Verlag, Stuttgart 2009, ISBN 978-3-8062-2335-4 , pp. 9-70.

- Helmut Schlichtherle, N. Bleicher, A. Dufraisse, P. Kieselbach, U. Maier, E. Schmidt, E. Stephan, R. Vogt: Bad Buchau - Torwiesen II: Building structures and municipal waste as indicators of the social structure and economic mode of an end-Neolithic settlement on Federsee. In: E. Claßen, T. Doppler, B. Ramminger (Eds.): Family - Relatives - Social Structures: Social archaeological research on Neolithic findings. (= Focus on the Neolithic. Volume 1). Welt und Erde Verlag, Kerpen-Loog 2010, ISBN 978-3-938078-07-5 , pp. 157-178.

- Helmut Schlichtherle: Comments on the climate and cultural change in the south-west German Alpine foothills in the 4th – 3rd Jts. v. Chr. In: Falko Daim , Detlef Gronenborn, Rainer Schreg (eds.): Strategies for survival. Environmental crises and how to deal with them . RGZM conferences 11 (Mainz 2011). Schnell & Steiner publishing house, Regensburg 2012, ISBN 978-3-88467-165-8 , pp. 155-167.

- Tomáš Sedláček : The economy of good and bad . Hanser, Munich 2012, ISBN 978-3-446-42823-2 .

- Walter Zimmermann (Ed.): The Federsee. (= The nature and landscape protection areas of Baden-Württemberg. Volume 2). Publishing house of the Swabian Alb Association, Stuttgart 1961, DNB 451222814 .

- Marion Papi: Those who know how to read nature's great book ... Walter Staudacher. A picture of life and time from the Federsee. Publisher Heidi Ramlow. Berlin 2011. ISBN 978-3-939385-05-9

Web links

- Federseemuseum

- NABU Center Federsee

- Film about the Federsee from 1985 authorized by the author

- Profile of the nature reserve at LUBW

- Landscape profile of the Federal Agency for Nature Conservation

- Map No. 179 (Ulm) of the Geographical Land Survey of the Natural Spatial Structure (PDF; 5 MB)

References and comments

- ↑ a b c d e f g Documentation of the condition and development of the most important lakes in Germany: Part 10 Baden-Württemberg (PDF; 411 KB)

- ↑ Opinions differ as to whether he is the second or third largest. The third-placed Titisee has a slightly smaller area of 1.3 km², but is 20 m deep and not just from 60 cm to a maximum of 2.80 m. In addition, its water surface is stable and, as in the case of the Federsee, which is only regulated by rainfall, is not subject to fluctuations due to transitions into a broad belt of moorland and reeds, which also vary with the seasons. The slightly different figures for lake and moorland areas in the literature can also be explained in this way, especially since it is difficult to precisely determine the boundary between water / land and moor / non-moor in the wide and sometimes quite irregularly protruding reed belt into the lake would be necessary for precise area calculations.

- ↑ The Federseemuseum. Retrieved April 16, 2020 .

- ↑ Many details, above all on nature as a whole, in the following article are taken from the internet publications of NABU (Naturschutzbund Deutschland e.V.), cf. nabu-federsee.de , these are not shown as a source in every individual case for practical reasons.

- ↑ Schlichtherle, Maps, pp. 18–23.

- ↑ Brockhaus Encyclopedia: German Dictionary. Volume 28, p. 2785.

- ↑ Schlichtherle, map p. 23.

- ↑ Schlichtherle et al., Torwiesen II, pp. 157–178.

- ↑ Keefer, p. 69 ff.

- ↑ Kubach, pp. 65-74.

- ↑ Müller-Karpe, Volume 2, pp. 71, 189; Cunliffe, pp. 276, f., 308 f., 310 f .; Buhl, p. 70 ff.

- ↑ For legends, fairy tales and customs, cf. especially the collections of Anton Birlinger from the 19th century.

- ↑ Gero von Wilpert : Specialized Dictionary of Literature (= Kröner's pocket edition . Volume 231). 3rd, improved and enlarged edition. Kröner, Stuttgart 1961, DNB 455687846 , p. 355 f., P. 535.

- ↑ Keefer, p. 87; Schlichtherle, p. 45.

- ↑ nabu-federsee.de

- ↑ books.google.de

- ↑ Historically used were u. a .: Kluge. Etymological dictionary of the German language. 24th edition. edit by Elmar Seebold . de Gruyter, Berlin 2002, ISBN 3-11-017473-1 ; Hermann Paul : German Dictionary. 6th edition. edit v. Werner Betz , Max Niemeyer, Tübingen 1966; Matthias Lexer's Middle High German pocket dictionary, Hirzel Verlag, Stuttgart 1961; Wilhelm Braune , Walter Mitzka: Old high German grammar. 10th edition. Max Niemeyer, Tübingen 1961; Walter Henzen : German word formation. Max Niemeyer, Tübingen 1965; Ulrich Knoop: Dictionary of German Dialects. Parkland Verlag, Cologne 2001, ISBN 3-89340-009-5 .

- ↑ Kluge, pp. 12, 69; Henzen, pp. 139 f., 273.

- ↑ Veck, S. 221st

- ↑ Beck, p. 185.

- ↑ Beck, p. 201.

- ^ Paul, p. 292.

- ^ Keefer, p. 89.

- ^ Kluge, p. 886.

- ↑ Beck, p. 230.

- ↑ Beck, p. 213 f.

- ↑ Possibly. ahd./lat. advises Hra ba ni / villa got re = "the beautiful country estate of / Hrabanus". These parchment abbreviations were mainly in property or foundation lists, and that is what it was about, then common to save space, as well as / (not 1!) As a syntax symbol or separator. Hraban is a first name that is still used here and there today, meaning "raven". Its most famous bearer was Hrabanus Maurus (approx. 780-846)

- ↑ Braune / Mizzka, §§ 125, A. 1, 153, A.1.

- ↑ Beck, p. 220.

- ↑ Beck, p. 217.

- ↑ Beck, p. 214.

- ↑ Herder Lexikon, Volume 1, p. 299.

- ↑ Kluge, p. 364.

- ↑ Recording of a wood grouse on jagd.it (MP3; 1.0 MB)

- ↑ Beck, p. 219.

- ↑ Cf. Braune / Mitzka, p. 199 ff: The ahd. Genitive singular of the n-declination of the name Ato reads Atin , ( i.e. house of Ato ), later ground down to Aten , cf. Uffo in " Zuffenhausen " etc.

- ^ Description of the Oberamt Riedlingen on Wikisource

- ↑ oberkaernten.info

- ↑ boari.de ( Memento of the original from March 6, 2016 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice.

- ↑ Description of the Oberamt Riedlingen / Chapter B 30

- ↑ zeno.org

- ↑ Keefer, pp. 41-48.