History of the parties in Germany

Above: Ludwig Loewe , Albert Haenel

Middle: Rudolf Virchow

Below: Albert Traeger , Eugen Richter

The modern parties in Germany emerged mid-19th century, when MPs in parliament joined forces to form tighter groupings. At first the liberals faced the conservative supporters of the monarchy; but many MPs were also unrestricted. Over the decades, the groups became permanent organizations that took on important state-supporting tasks, especially after 1918.

The Frankfurt National Assembly of 1848/1849, the first all-German parliament , was particularly important for the development of political parties . In the 1860s, the first Germany-wide parties emerged , initially the liberal German Progressive Party (1861), later the General German Workers 'Association (1863) and the Social Democratic Workers' Party (1869) as well as the Catholic Center Party (1870).

In the German Reich since 1871, the parties could have a say in the legislation of the Reichstag. Two conservative parties and the National Liberals (right-wing liberals), which split off from the Liberals in 1867, supported the government . Center and the rest of the Liberals also worked with the government from time to time. The Social Democratic Party of Germany (SPD), as it has been called since 1891, remained in fundamental opposition to the state at the time. In addition, there were several regional and minority parties, interest parties and several small anti-Semite parties in the Reichstag .

Center people, left-wing liberals and, from 1918, also social democrats took part in the government of the Reich . In the Weimar Republic from 1919 onwards, the parties were mostly unable to form a constructive parliamentary majority. The larger parties from the empire largely remained; some renamed themselves, the conservatives were absorbed into the German National People's Party . The minority parties disappeared; In addition, there were other interest parties and new types of extremist parties, above all the Communist Party of Germany (KPD) from the left and the National Socialist German Workers' Party (NSDAP) from the right. The latter took power in 1933 and banned all other parties or forced them to dissolve themselves.

After the Second World War it was initially four parties that were allowed by all four victorious powers in the respective occupation zones : The Christian Democratic Union of Germany as a Christian-conservative-liberal collection, the liberal Free Democratic Party (sometimes under different names locally), the SPD and the KPD.

After the forced unification of the SPD and KPD, the dictatorship of the Socialist Unity Party of Germany (SED) arose in the GDR . There were also the so-called block parties .

In the Federal Republic of Germany the KPD immediately lost in the elections and was banned in 1956 . After a phase of new, smaller parties in the 1950s, the Union parties and the SPD remained as popular parties in 1960 , each of which formed a coalition with the FDP. In 1983 the ecological-alternative party of the Greens, founded in 1980, moved into the Bundestag for the first time .

In the course of reunification in 1990, the GDR state party, SED, became the party of democratic socialism ; In 2007 this merged with the WASG, which was mainly founded by former Social Democrats, to form the Left Party . Furthermore, there were and are many other parties at the federal, state and municipal levels that never made it into the Bundestag.

In the 2017 federal election , the Alternative for Germany (AfD) party was elected to the German Bundestag for the first time with 12.6% of the valid votes , in which it is now represented as the third largest parliamentary group.

At the end of 2017, the SPD was again the largest party in Germany with around 443,000 members, while the number of CDU members had fallen to below 430,000. The other parties represented in the German Bundestag (AfD, FDP, Left, Greens), on the other hand, recorded a significant increase in some cases.

From Vormärz to the founding of the Empire in 1871

The formation of parties is linked to the existence of members of parliament. Parliaments in the modern sense did not exist in most countries of the world until the 19th century, because, for example, the Reichstag in the Holy Roman Empire was a representation of individual states. Even in cities, councilors were typically representatives of social groups such as certain craft establishments. One speaks of an estates constitution in which not voters but estates are represented.

"The formation of parties in a non-party constitution is an act of revolution," wrote the constitutional historian Ernst Rudolf Huber . When parties embody ideas and interests appear in a non-party state, "society rises against the state" and transforms it. The monarchs in Germany and their supporters could only have prevented this emergence if they had enforced their party bans with extreme consistency, i.e. if they had abolished the parliaments.

South German parliaments

Apart from the beginnings in the time of Napoleon, the history of the German parliament begins after 1815 in southern Germany. Baden, Württemberg and Bavaria had constitutions and parliaments there with two chambers each. The upper houses were chambers of nobility, the people's houses were also still composed of estates. Only those who owned property or paid a certain amount of taxes were allowed to vote.

The chambers had few rights and were more like discussion forums. Their deputies came from the wealthy or educated classes, from rural and commercial circles, and also from the academically educated civil servants. Some MPs stood behind the government, others, the liberals, formed the opposition . The liberals' spokesmen in particular were often civil servants.

The traditional designation of the liberals as the left and the conservatives as the right is even older and goes back to the French Revolution. In what was then the National Assembly, those loyal to the king sat on the right-hand side (seen from the President of Parliament), the revolutionary-minded on the left.

March 1830–1848

Already in Vormärz , the period from 1830 before the March Revolution of 1848, there were “preliminary forms of a modern party system” ( Karl Rohe ). However, at that time there was no all-German parliament, so development began at the level of the individual states in southern and central Germany. On July 5, 1832, in response to the Hambach Festival , the Bundestag of the German Confederation once again tightened press, association and assembly law. Accordingly, the member states had to prohibit “all associations that have political purposes or are used for political purposes under a different name” (Section 2 Federal Decree). The same applied to public speeches of political content (Section 3.2) and the wearing of political badges (Section 4).

However, there were many non-political associations in Germany. In them one already trained oneself for organizational questions, for example through membership recruitment, handling of statutes and the creation of programs, and the holding of elections. Only in this way was it possible during the revolution of 1848 to bring about organizations capable of acting within a few weeks.

Parties slowly emerged, often around magazines. They were not bearers of power, but ideological parties. The liberals identified with the people and directed themselves against parties, but also against those loyal to the government, the clericals (loyalty to the church) and the seducers, the demagogues.

Liberals and Radicals

Political moderates of classical liberalism and radicals of left-wing liberalism separated, among other things, the question of whether violence is justified in political struggle.

The moderate liberals believed that the inequalities between people were the result of differences in talent and performance. At best, inequality should be limited, through certain taxation, including inheritance tax, and through access to education.

The aim of moderate-liberal liberalism was initially the realization of freedom rights and the constitutional state in a constitutional monarchy , for example on the model of the Glorious Revolution of 1688/1689. German liberal constitutionalism was finally realized at the end of the 19th century.

Around 1840 the radicals separated from liberalism; they stood up for equality as a prerequisite for freedom, in case of doubt for equality. They did not want any limitation of state power or a separation of powers, but rather the rule of parliament and perhaps elements of direct democracy (referendums). They wanted to enforce popular sovereignty through universal and equal suffrage; they were not only against the old system, but also against the liberal property and educated bourgeoisie.

The main goal of radical liberalism was the republic (abolition of the monarchy and dominance of the church). Philosophically, the radical liberals came from the left Hegelians . They wanted the emancipation of man through the weapon of reason. The criticism of religion, as Strauss and Feuerbach expressed it, led to revolutionary criticism of the state and society. The idea had to become reality, the revolutionary intelligentsia had a self-confident claim to power. The radicals rallied, among other things, around the Halle yearbooks for German science and art (since 1838; since 1841 German yearbooks ). The Rheinische Zeitung (1842/1843) was also important .

Labor movement

Just as the radicals broke away from the liberal movement, so did the labor movement from the radical one. The labor movement wanted to improve the situation of wage workers and manual workers and fight for political rights. But it was not yet necessarily socialist, and it was not initially a movement of the lower classes - they were excluded from politics anyway. Rather, the labor movement was a combination of intellectuals and journeymen abroad (in exile). There was free speech, which was used for theoretical discussions.

The early socialism , emerged from the democratic radicalism that saw itself as the heir of the French Revolution and continuation of liberal emancipation movement. He rejected the juste milieu , the hierarchical society of the liberals, just as the radicals did. But he went beyond that, was for common property and against liberal individualism and the limitation of the state. Thus socialism also had anti-liberal points of contact with the conservatives. However, he was not backward-looking but forward-looking and stood on the ground of the industrial revolution.

The revolutionary writer Georg Büchner wrote in July 1834 under the title “Peace to the Huts! War on the Palaces ":

“The prince is the head of the bloody hedgehog that crawls over you, the ministers are his teeth and the officials are his tail. [...] what are the constitutions in Germany? Nothing but empty straw from which the princes knocked the grains out for themselves. [...] Germany is now a field of corpses, soon it will be a paradise. The German people are one body, you are a member of this body. It doesn't matter where the pseudo-corpse begins to twitch. When the Lord gives you his signs through the men through whom he leads the peoples out of servitude to freedom, then arise, and the whole body will rise up with you. "

It took decades for the labor movement to become a social power, and when it began it was not yet clear that Marxism would become dominant. There were also Protestant and Catholic initiatives committed to the welfare of the workers, for example by the Hamburg pastor Johann Heinrich Wichern and the Westphalian clergyman Wilhelm Emmanuel von Ketteler .

conservative

Conservatism was the force of persistence, class and romantic. In Prussia it was modernized by the legal philosopher Friedrich Julius Stahl , a former fraternity member and baptized Jew who came to Berlin from Bavaria. According to his program, the Christian state should be based on Christian norms and institutions, not secular ones. It should be inherently connected to the church and, for example, with marriage law, ensure that society remains Christian.

Thanks to Stahl, conservatism no longer rejected the modern state, saw in it "not a quasi private, class and particularistic structure of rule and property, but the only and undivided community to which all public authority belongs" (Nipperdey). The constitution should not be liberal, but be oriented towards the monarch, with only a limited role for parliament. Stahl referred to the English example and the class roots of Parliament there.

From 1840 to 1862 there were four groups of conservatives. The class conservatives with Leopold von Gerlach and Friedrich Julius Stahl, the “highly conservatives”, rejected absolutism as well as liberalism. Both are products of rationalist thinking. Their advocacy for the kingdom arose from the idea of divine right . They started out from the “whole” and rejected the division of Europe into nation states; they advocated natural, "organic" development, but not revolutionary overthrow or the "progressive" skipping of stages of development. Their legitimism was based on the fact that the old rights of the estates, but also the rights of a dethroned monarch, continued to apply.

The socially conservative group, with Lorenz von Stein and Victor Aimé Huber, called for social royalty. The social question should not be solved by the fact that the factory owners adopt the methods of the agricultural patriarchs. Rather, the monarchical state should become a welfare state. The Inner Mission of Protestant clergymen, the labor protection laws and Bismarck's social insurance later grew out of this direction .

National conservatives, including Leopold von Ranke and Moritz August von Bethmann Hollweg , strove for a German nation-state based on the English model; they were also prepared to recognize fundamental rights. The nation-state should, however, be organized as federally as possible, have a strong monarch and not emerge from a revolution.

The group with Gustav von Griesheim and Otto von Manteuffel is called state conservative . Their supporters had great power in the German states, not least in Prussia, while the conservative state theory had already passed over them. She stood up for a late absolutist, all-powerful state based on monarchy, bureaucracy, the military and the state church.

Catholics

Before the French Revolution, the church always appeared together with the state. That was no longer so natural afterwards; however, the Church wanted to continue to influence people's lives, especially through such life-changing institutions as school and marriage. In these areas, however, she had to come to terms with the state. The attempts to repel the controls and interventions by the state gave rise to a political movement outside the official church. The Catholic was faced with secularization (secularization), the prevailing trend in bourgeois society.

The Catholic masses were mobilized and organized only slowly after 1815, on the basis of pilgrimages and church leaflets, and from the 1840s also through associations. The actual formation of the party occurred in 1838, after the event in Cologne in 1837: the Prussian state had imprisoned the Archbishop of Cologne in a dispute over mixed confessional marriages. This became the Catholics' first pan-German experience, which politicized and polarized. The Protestant and Catholic Conservatives parted, liberals and radicals turned against Catholicism. The combat pamphlet Athanasius and the Berliner Politische Wochenblatt by Joseph Görres date from this period .

The conservative Catholics emphasized order and tradition and that man is not the creator and ruler. They saw the revolution as a modern sin. The liberals would take the hold of the given, the bureaucratic-authoritarian state is also modern demon. The origin of modern misfortune is the Reformation with its subjectivism, from which the Enlightenment, absolutism and the revolution in general originate.

German Revolution 1848/1849

Following revolutionary events in France and other European countries, the “ March Revolution ” took place in Germany in March 1848 to make Germany a unified country with a parliamentary constitution. Many monarchs, in fear of terror as in the French Revolution, appointed liberal governments. As early as March 5th, liberal and democratic politicians met in Heidelberg for the so-called pre-parliament, the former for the monarchy, the latter for the introduction of the republic. Together they then voted for elections to a national assembly that would answer the question of monarchy or republic. An extreme left around Friedrich Hecker stuck to their demand that the pre-parliament should declare itself to be a revolutionary convention and stay together permanently, and left the assembly for some time. The moderate left around Robert Blum remained.

The elections to the National Assembly ran differently depending on the state, but according to the requirements of the Federal Election Act of the Bundestag. The rule that only “self-employed” were allowed to vote was interpreted very generously, so that on average around eighty percent of the (male, adult) population in Germany voted. Since there were only rudimentary parties, the elections were mostly personality choices.

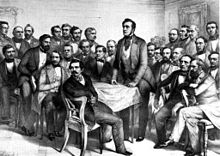

Both the highly conservatives and the socialists were absent from the “Paulskirchenparlament”, named after a Frankfurt church where it met. The Catholics were rather weakly represented and also divided into several groups. The different factions (members of a certain political direction) named themselves after the respective hotel or restaurant in which they met:

- Approx. forty right-wingers, that is, moderate conservatives (Steinernes Haus, then Café Milani ): They wanted to preserve what already existed, were in favor of the church and a federalist solution, i.e. a state that would give the individual member states a lot of freedom.

- Approx. 120–130 members of the Right Center, the constitutional liberals ( Casino ): The aim was to work with the governments of the German states to achieve a balance between the state and the individual. If necessary, concessions should also be made on questions of freedom. The best-known representative of this direction was the President of Parliament and later Prime Minister Heinrich von Gagern . It later split into several parts.

- Approx. 100 MPs in the Left Center, the left liberals ( Württemberger Hof ): It campaigned for popular sovereignty and the rights of parliament, including the Paulskirche. In October a right ( Augsburger Hof ) and a left ( Westendhall ) group split off.

- Approx. 100 moderate democrats ( Deutscher Hof ): Robert Blum and his supporters were in favor of the republic and the rule of the people and parliament.

- Approx. 40 radicals, the extreme democrats ( Donnersberg ): Hecker's supporters wanted to continue the revolution if necessary.

Despite the formation of groups, there were still many non-group members and group changers, and the groups did not always vote as one. In principle, however, a parliamentary group member was expected to join the parliamentary majority on important issues. Later, the right and the center regrouped according to large and small Germans, who each needed the left to work together.

Outside of the all-German parliament, there were developments in the parliaments of the individual states as well as extra-parliamentary movements:

- The Catholics gathered for example in the "Pius Associations for Religious Freedom", with about 100,000 members; in August they collected 273,000 signatures for a petition to Paulskirche to uphold the rights of the church. After an objection from Rome, they dropped the demand for a national primate (chairman of the bishops in Germany) and a German synod. It was more important for them to protect the church from state interference.

- The conservatives sought strategies against the revolution. In July 1848, the highly conservatives gathered behind the Neue Preußische Zeitung (" Kreuzzeitung "), and associations of large estates and the Protestant church were formed. Important support came from military circles, which still had a lot of influence at the courts. From these circles comes the sentence that only soldiers would help against democrats.

- Radicals and democrats feared the counter-revolution and therefore wanted to push the revolution all the more radically. Should the Paulskirche fail, they wanted to set up a “kind of Jacobin temporary dictatorship” with totalitarian features (Nipperdey). In June, a Democrats' Congress with two hundred participants was held in Frankfurt, calling for the establishment of democratic-republican associations. The Democrats finally broke away from the Liberals. In September there was even a radical uprising in Frankfurt in which two Conservative MPs were killed. Above all, this turned the center against the left and ultimately strengthened the conservatives.

In the form of workers' associations, there were already groups that adhered to one or the other formulation of " socialism ". The Communist Manifesto , for example, dates from the year of the revolution . These groups were not represented in Paulskirche and at that time could not be clearly distinguished from bourgeois radicalism.

The Frankfurt MPs are working on an imperial constitution including the basic rights of the German people . It also enacted imperial laws and established a provisional central power as an all-German government. On March 28, 1849, the Paulskirche elected the Prussian King Friedrich Wilhelm IV. As Emperor of the Germans, who did not accept the imperial crown. Instead he fought the National Assembly and forcibly suppressed the revolution.

National parties after 1849

The decade after the failed March Revolution is called "reaction time". Parties and political associations were banned. This only relaxed in the Kingdom of Prussia after Wilhelm I took over the official duties of his sick brother in 1858 .

liberal

The first German party with a fixed party program was the liberal German Progressive Party , founded in 1861 . She campaigned for a German nation-state on a democratic and parliamentary basis:

“We are united in our loyalty to the king and in the firm conviction that the constitution is the indissoluble bond that holds prince and people together. [...] For our internal institutions we demand a firm liberal government which sees its strength in respect for the constitutional rights of the citizens [...]. "

The Progressive Party, which was powerful in the Prussian state parliament, split in 1867 into a left and a right direction. That was a belated consequence of the Prussian constitutional conflict of 1862. Prime Minister Otto von Bismarck , having received no support for his military budget from the liberal state parliament, simply acted without the consent of the state parliament. After the victory over Austria in 1866 he asked for a subsequent justification with the so-called indemnity bill ; only indirectly did he admit to having acted illegally. While the left-wing liberals rejected the offer of reconciliation, the right-wing accepted it and subsequently founded the National Liberal Party . It was oriented towards small German, so wanted a Prussian-led Germany without Austria , and later mostly worked together with the Reich government.

South German liberals, on the other hand, founded the left-wing liberal German People's Party . They wanted a large German solution , that is, a federalist Germany including Austria. In the Reichstag of the North German Confederation (since 1867) the German People's Party also worked with socialists who were also anti-Prussian.

Socialists

In 1863, the first forerunner of the Social Democratic Party of Germany was formed in Leipzig , the General German Workers' Association (ADAV). Its main initiator and president was Ferdinand Lassalle from Breslau , who viewed the liberals as the main enemy, who had betrayed the revolution of 1848. When he died a year later, the association had only 4,600 members, but it was already a centralized organization.

Lassalle spoke of the "helping hand of the state" that the workers' associations need in the fight against social exploitation:

"If the legislative bodies of Germany emerge from universal and direct suffrage - then and only then will you be able to determine the state to subject itself to its obligations [...]. Organize yourself as a general German workers' association for the purpose of legal and peaceful, but tireless, incessant agitation for the introduction of general and direct suffrage in all German countries. […] On the part of the governments, one can sulk and quarrel with the bourgeoisie about political rights. Even you can be denied political rights and thus also the universal right to vote, given the lukewarmness with which political rights are understood. But the universal suffrage of 89 to 96 percent of the population is understood as a stomach issue and therefore also spread through the whole national body with the warmth of the stomach - do not worry, gentlemen, there is no power that would oppose this for long! "

In 1869, emerging from the short-lived Saxon People's Party of 1866, the Marxist-oriented Social Democratic Workers' Party (SDAP) was created on the initiative of Wilhelm Liebknecht and August Bebel , which initially - for various reasons - was in competition with the ADAV. Among other things, the party, which is more domiciled in Saxony, Bavaria and other non-Prussian areas, was set up for Greater German, while the ADAV did not refuse tactical cooperation with the Prussian government. In 1875 the two parties united in Gotha to form the Socialist Workers' Party of Germany (since 1891 under the name known today, SPD).

conservative

Like the Liberals, the Conservatives were divided over Bismarck's policies. The old conservatives invoked the principle of legitimacy (the traditional rights of the princes) and therefore condemned that Prussia annexed areas such as Hanover and deposed their princes. They also rejected the war against Austria in 1866. The more modern free conservatives (since 1866/1867, later at the level of the Reich, the German Reich Party ) supported Bismarck.

Catholics

Catholic MPs naturally formed their own parliamentary groups. Hermann von Mallinckrodt summarized the performances in Prussia in a draft program in May 1862:

“The essential foundation of a just, free state consists in the doctrines and principles of Christianity. […] The higher the occupation and law of the authorities, the less it should be misunderstood that their legal sphere is restricted in the rights of individuals, families and corporations […]. The principles of morality and law must also be guiding stars in politics. Unworthy of one's own right who disregards the law of others. Therefore combat all revolutionary tendencies, be it in external relations or in the internal sphere of the state. A German policy which fully appreciates the balance of power as well as the interests of our Prussian state and does not allow the latter to be followed by any foreign special interests, but which also does not seek the standard for the needs and national tasks of the German people in narrow-minded care of their own special interests.

In 1870 the Catholic Center Party was formed , named after the fact that the Catholic MPs mostly sat between the Liberals on the left and the Conservatives on the right in parliament. In retrospect, it is considered to be the first German “people 's party ” because its voters came from all social classes. Their share of the vote has remained relatively the same for decades at ten to twenty percent. Compared, for example, with the Dutch Catholic Party, the center tapped the Catholic voter potential rather poorly, because the Catholics made up thirty to forty percent of the German population.

Empire 1871–1918

Already in the North German Confederation since 1867, but also in the German Empire since 1871, the Reichstag was an important organ with which the parties could influence state policy. They helped determine the legislation, but the government was set up by the emperor. The role of the Reichstag and thus also of the parties was also restricted by federalism, by the strength of Prussia in the Bundesrat and by certain restrictions on budget law and decisions about the military.

The parties of the 1860s essentially continued to exist in the German Empire. The socialists united in 1875 (see Gothaer Program ) renamed themselves the Social Democratic Party of Germany in 1891 , the left-wing liberals (or those who did not belong to the national liberals) were at times spread over three different parties.

In 1876 the more traditional conservatives formed at the imperial level. Despite the name German Conservative Party , it was primarily a party based in Prussia, whose interests it also represented. In 1887 of 74 members of the Reichstag, 53 were nobles in this party of landowners, some of them senior officers. They affirmed the new empire, but wanted to preserve the independence of monarchical Prussia, which remained the fulcrum of their endeavors. This attitude also meant that the German Conservative Party differentiated itself from the völkisch nationalists such as the Pan-German Association , even though it appeared contradicting the minorities in Germany. She was friendlier to the Prussian-affirming Lithuanians, hostile to the anti-Prussian Poles.

There was also the Christian Social Workers' Party , founded in 1878 , which was the first to include anti-Semitism in the party program. The party founder and Berlin cathedral and court preacher Adolf Stoecker made anti-Semitism socially acceptable. In addition to this, other anti-Semite parties also entered the Reichstag, but they never achieved political importance. The German Social Party, for example, demanded in 1899:

“It is the task of the anti-Semitic party to deepen the knowledge of the true nature of the Jewish people [...]. Thanks to the development of our modern means of transport, the Jewish question should become a world question in the course of the 20th century and, as such, be solved jointly and finally by the other peoples through complete separation and (if self-defense dictates) the ultimate annihilation of the Jewish people. "

Furthermore, there was always a certain number of MPs in parliament who belonged to regional parties or minorities. Together they made up about ten percent. These were the "Alsatians", that is, the vast majority of MPs from Alsace-Lorraine who were otherwise quite close to the center, similar to the Polish MPs. There were also some Danish MEPs. These three groups disappeared from parliament after 1918, corresponding to Germany's loss of territory. The German-Hanover Party , which emerged from the Hanover election association in 1869/1870 after Prussia annexed Hanover in 1866, was permanent .

Elections and regional distribution

The right to vote differed in the individual countries; For example, Prussia had three-tier voting rights until 1918 . The election to the Reichstag, on the other hand, was uniformly general, equal and direct (and, with restrictions, also secret). In principle, all men aged 25 and over were eligible to vote, with the exception of members of the military, prisoners, the incapacitated and men who lived on poor relief. In 1874, 11.5 percent of men were excluded from the election, in 1912 it was only 5.9 percent. That was because the criteria were interpreted differently and the electoral roll was kept better.

In addition to the electorate, the military could also be elected. If a member of parliament became civil servant, he had to give up his mandate. Since there were no diets (money for members of parliament) until 1906 , the Social Democrats were fundamentally disadvantaged because their representatives often came from poorer backgrounds. However, their MPs were often party employees or editors of party newspapers, which in turn tied them more closely to their party.

The vote took place according to an absolute majority vote in one-person circles ; if no candidate achieved an absolute majority in a constituency, a runoff election soon followed. Politically related parties agreed on a promising candidate in advance.

In some cases, there were large differences between a party's share of votes and mandate, as is customary in majority elections. A party usually only competed where its candidate had a chance of being elected. That is why the left-wing liberals were primarily a West and South German party, while the conservatives had their strongholds in the east. The center was strong in the south, parts of the west and in Upper Silesia, where Catholics lived. The only really Reich-wide party was the SPD, which had put up candidates in almost all constituencies since 1890. In the case of hopeless constituencies, one speaks of “counting candidates” who gave the local SPD supporters the opportunity to vote for their party. This mobilized the SPD voters and generated a high proportion of votes with which one could protest against the majority electoral system (and the relatively few seats for the SPD) (the Poles proceeded similarly).

In addition to the majority vote per se, constituency and runoff elections were two important factors in determining the strength of parties in parliament. The constituencies were not adjusted to the changes in the population (growth through births, emigration and immigration). This put urban Germany at a disadvantage compared to rural Germany, that is, left-wing liberals and social democrats compared to the conservatives and the center.

Party organization

Until the 1880s, being a party primarily meant supporting a faction. This was especially important for election campaigns; initially there was hardly any organization between the elections. You were nowhere a member, at most in an association that was culturally close to a party. The center could count on the support of the clergy, the conservatives on the bureaucracy and the big landowners. The liberals had to find new helpers for the election campaign.

Over time, election-to-election continuity emerged from the local election committees. These committees replaced modern parties until 1899, when political associations were still banned. Around this time there were more and more social groups with new demands, often economic ones. The voters were more often employees, no longer self-employed craftsmen and farmers. Society, including its lower classes, became increasingly interested in politics. The party organizations were therefore expanded to counter populists (such as the anti-Semites). Election campaigns lasted longer and were more expensive. Not only should their own political speakers be trained, but the people as a whole should be trained, writes Margaret Anderson. Typical for this were the political encyclopedias with titles such as electoral books or electoral catechism. The classic was the ABC book for free-spirited voters by the liberal Eugen Richter .

The Social Democrats stood for the new way of party organization and electoral mobilization. The other parties had to react to this, above all the liberals, while Catholics and conservatives were more likely to fall back on church and association structures. Overall, the dignitaries party type remained dominant. The headquarters had little money, donations mostly went to local organizations and candidates.

Powerlessness of the parties

According to the constitution , the parties had no influence on the formation of a government, but they could have asked the question of power, as has happened in other countries. A majority in the Reichstag could have rejected the imperial government's bills and budget proposals in general, in order to force the emperor to set up a government with members of the majority parties. This didn't happen for several reasons:

- Above all, Otto von Bismarck , Chancellor of the Reich from 1871 to 1890, was very adept at playing the parties off against each other. To make them compliant, he did not shy away from defamation and even persecution; "Hostility to the Reich" was his accusation. Organized Catholicism experienced this with the Kulturkampf (about until 1878) and social democracy with the socialist laws (1878–1890). The Liberals partially voted for anti-Catholic and anti-socialist legislation. Though dissenters were not murdered by the state, they were imprisoned. Many careers have been destroyed.

- Bismarck and also some imperial politicians after him threatened indirectly and sometimes clearly with the establishment of a new political system in which the parties would have even less a say ("coup policy"). This discouraged the parties from asking the question of power.

- The parties represented different views and interests and also endeavored not to let those who think differently get too far up:

- Above all, the two conservative parties and the National Liberals , which together were called the cartel parties , profited from the existing system and feared political and social changes.

- But the center, which would have had a majority with left-wing liberals and social democrats as early as 1890, preferred to come to terms with the government. In terms of cultural policy and school policy, it was against the left-wing liberals and social democrats, while with the social democrats it shared certain socio-political views.

- Even the left-wing liberals, who advocated democratization, partly worked together with the cartel parties because they feared Catholicism and, even more, feared social democracy.

- The Social Democrats were against government participation, partly because of their bad treatment, partly for reasons of principle. According to the harsh socialist laws, in 1891 they adopted the Marxist Erfurt program . This direction was subsequently criticized by the so-called revisionists around Eduard Bernstein . The historian Helga Grebing called the SPD at that time an “isolated class party of the German industrial workers”.

Even so, the old forces' front was not unshaken. After the Reichstag elections in 1912, with great profits for the SPD, it became increasingly difficult to maintain the old conditions.

First World War 1914–1918 and November Revolution

At the beginning of the First World War , Kaiser Wilhelm II offered the parties a " truce ". The nation should fight together; he expected the parties to approve the war credits . Only a very small part of the SPD around Karl Liebknecht resisted. This became the seed for the Independent Social Democratic Party of Germany (USPD) in 1917; the previous SPD was briefly called the majority Social Democratic Party of Germany (MSPD). Another left-wing revolutionary group, the Spartakusbund , formed the nucleus for the later Communist Party of Germany (KPD).

On July 6, 1917, the MSPD, the Liberals and the Center founded an intergroup committee and demanded a peace of understanding without territorial expansion and further parliamentarization. Left members of the National Liberals such as Gustav Stresemann also advocated parliamentarisation, but advocated annexations. In that year even a conservative center politician became Chancellor, Georg von Hertling . However, the government remained weak towards the Reichstag on the one hand and the Supreme Army Command on the other, which benefited from the emperor's favor.

On September 29, 1918, the Supreme Army Command informed the Emperor and Reich Chancellor of the hopeless military situation. Ludendorff demanded an armistice petition . He recommended that a central demand of the American President Wilson be met and that the government should be placed on a parliamentary basis in order to achieve more favorable peace conditions. This means that the democratic parties should be solely responsible for the impending surrender and its consequences.

Ludendorff's situation report shocked the government as well as the party leaders afterwards. Nevertheless, the majority parties were ready to take over government responsibility. Since Chancellor Hertling rejected the parliamentary process, the Emperor appointed Prince Max von Baden , who was considered liberal, as the new Chancellor on October 3rd . In his cabinet also Social Democrats first entered.

With the October reform of October 28, 1918, the Chancellor had to have the confidence of the Reichstag from then on. The German Reich had thus changed from a constitutional to a parliamentary monarchy . From the perspective of the SPD leadership, the so-called October Constitution fulfilled the party's most important constitutional goals. After the forced abdication of the emperor on November 9th, the country went in the direction of a republic with a new constitution, which was passed on August 11th, 1919.

Weimar Republic 1919–1933

requirements

The parties in the Weimar Republic did not differ significantly from those in the German Empire, as the social and moral milieus behind them remained the same. This means social groups, ideological camps, each united by religion, tradition, property, education and culture. There was always a conservative, a Catholic, a bourgeois-Protestant and a socialist-proletarian milieu. New types of parties were added, which appeared with an increasingly authoritarian claim to leadership internally and externally. As mentioned, the direction that ultimately found itself in the Communist KPD had split off from the SPD . The National Socialist NSDAP had ideological forerunners in the anti-Semitic parties and the Volkisch - Pan-German circles of the empire.

During the Weimar period, the parties not only had to take care of the nominations for the Reichstag and the state parliaments, but also for the election of the Reich President. In general, they had to take over the entire management of the state, including in areas of politics that were previously more the domain of the imperial government, namely the military and foreign policy. Not least because of the difficult situation in Germany, the parties found it difficult to form governments with a parliamentary majority and to take responsibility.

To simplify matters, it is often claimed that the Weimar electoral system led to party fragmentation and a multi-party system. Rather, however, the multi-party system of the imperial era remained; there were still usually about ten to fifteen parties in the Reichstag. Only a handful of them were really relevant. It was not the number of small, but the strength of the extremist parties that became fatal for the republic. This is particularly true of the time since the Great Depression in 1929, when the party system changed radically: the majority of the votes of the conservative and liberal parties were absorbed by the NSDAP.

The Weimar proportional representation system was not entirely purely proportional representation, because of a remaining vote count, but it ensured that the regional distribution of votes was unimportant. Now it was also worthwhile for the conservatives, for example, to campaign more actively than before outside the East. Agreements between the parties for the list of candidates lost their meaning, except for the presidential election, which encouraged the formation of camps throughout the Reich. For the first time in German history and earlier than in many other countries, women were allowed to vote in 1919.

The party organization became more important, the parties made the step from a dignitary to a member party. The leadership was tightened, an apparatus built. The model for the parties was usually the pre-war SPD. Furthermore, a candidate now had to prove himself above all in the party bureaucracy in order to be put on a list.

Parties of the democratic center

The Social Democratic Party of Germany lost much of its left wing to the USPD. Part of the USPD membership went back to the SPD in 1922, which was the strongest parliamentary group until 1932. The SPD had around twenty to thirty percent of the vote, but after 1923 only participated in government from 1928–1930.

The Liberals originally wanted to form a large common people's party in 1918. However, personal and content-related conflicts meant that the division into left-wing progressives (now in the German Democratic Party , DDP) and national liberals (now German People's Party , DVP) was retained. Despite sometimes strong friction, however, they almost always worked together in government and, alongside the center, became the actual governing parties of the republic (until 1931/1932). If the earlier established DDP was the far stronger of the liberal parties, the relationship quickly turned around. The highest election result was achieved by the DDP in 1919 with over 18 percent and the DVP in 1920 with over 13 percent. With a sharp decline, even in 1930 they still received over eight percent. At the latest in the three Reichstag elections of 1932 and 1933, however, they became numerically insignificant.

At the beginning of the Weimar Republic, many leaders of the DDP had reached high state offices, but that changed in the course of the 1920s. The election defeat of 1928 led to great uncertainty, to which party leader Erich Koch-Weser also contributed. At that time, the founding of a broader people's party was suggested, whereby one thought primarily of a merger with the DVP and its charismatic leader Stresemann. In 1930 Koch-Weser tried to re-establish it, which included the People's National Reich Association . These black-white-red young liberals were only a reinforcement in terms of personnel, not ideally. Werner Stephan speaks of a "process of self-dissolution which the leadership set in motion with fear of existence since 1928". Members of the left wing left the party, but so did the Volksnationalen after the Reichstag election. In November 1930, however, the DDP renamed itself to the German State Party .

The DVP was the party of business, industry, the upper middle and upper classes. The relevant interest groups had a major influence on the nomination of candidates in parliamentary elections. There was a conservative trait in it, nevertheless and despite its rather small size, the party played a “decisive role for the Weimar Republic”, according to Lothar Döhn.

The party of the Catholics remained the center , although in 1919 there had been approaches to an all-Christian people's party. It is characteristic of the center that it achieved very consistent election results of around eleven to thirteen percent during the Weimar period. If you add the Bavarian spin-off BVP , you get roughly the strength of the center before 1918. However, the BVP was significantly more right-wing than the center and, for example, voted against the center candidate Wilhelm Marx in the 1925 presidential election .

One valued the intellectual order of the center in a time of decay and disorientation. While Catholicism was seen as premodern and culturally backward in the empire, it has now come as if from exile, says Karsten Ruppert with reference to a contemporary contribution.

Since the center did not necessarily stand for a certain form of government, but for an abstract Christian political doctrine, the transition from the empire to the republic was not difficult for him: “With the old flag into the new era” was a book title from 1926. In Weimar times the Party had the greatest responsibility, but that meant that it was barely able to achieve its own Christian or Catholic goals. She saw constant government participation primarily as a sacrifice made out of a sense of responsibility.

conservative

Conservative, right-wing national liberals, anti-Semites and a few other groups found themselves in the German National People's Party (DNVP) in 1919 . The worst was to come to terms with the defeat of the war and the emperor's abdication:

“Standing above the parties, the monarchy most surely guarantees the unity of the people, the protection of minorities, the continuity of state affairs and the incorruptibility of public administration. The individual German states should have a free decision on their form of government; for the empire we strive for the renewal of the German empire established by the Hohenzollern. [...] For us the state is the living body of the people, in which all members and forces should come to active cooperation. The […] people's representative body deserves decisive participation in legislation and effective supervision of politics and administration. "

The DNVP was only briefly represented in Weimar governments; so it did not take on the role of a broad right-wing bourgeois party within the party system. As early as 1922 she lost radical anti-Semitic members to the Deutschvölkische Freedom Party , which at times worked with the NSDAP.

In key votes, such as the 1924 Dawes Plan , around half of the DNVP MPs voted for the government bill, which led to serious conflicts between moderates and radicals in the party. From 1928 to 1930 the party lost half of its MPs and votes, and smaller parties split off, such as the People's Conservative Reich Association of 1929 (Conservative People's Party since 1930). Overall, the DNVP had between seven and fifteen percent of the vote, with the exception of the two elections in 1924 when it received around twenty percent.

Independent social democrats and communists

A group around Karl Liebknecht that refused to support the war was expelled from the SPD parliamentary group in 1915. This gave rise to the Independent Social Democratic Party of Germany in 1917, to which the Spartakusbund joined:

“The conquest of political power by the proletariat heralds the liberation of the working class. To carry out this struggle, the working class needs the independent social democracy, which stands wholeheartedly on the ground of revolutionary socialism, the trade unions, which are committed to the irreproachable class struggle and are to be transformed into fighting organizations of the social revolution, and revolutionary action. "

For a short time the USPD achieved large numbers of members and electoral successes that brought it close to the SPD. A majority in the party voted in 1920 to join Lenin's Communist International and the KPD. Most of the rest of the USPD returned to the SPD in 1922, while the remaining members continued as a splinter party until 1931.

The KPD experienced fierce internal party disputes in the course of the 1920s. According to the communism expert Hermann Weber , the party has been unconditionally aligned with Stalin since 1924 . Of the 16 members of the highest party organ at the time, only two were in office in 1929, Ernst Thälmann and Hermann Remmele, who was executed in the Soviet Union in 1939 . The KPD's “ultra-left” policy contributed significantly to the downfall of the Weimar Republic. In the Reichstag elections it usually came to around ten percent, in 1932 it came to just under seventeen percent.

NSDAP and Third Reich 1933–1945

After the First World War, a large number of right-wing splinter groups had emerged. One of them was the German Workers' Party of January 1919, which Adolf Hitler joined in the same year . In 1921 he became the chairman of the party, which has since been renamed the National Socialist German Workers' Party, strictly organized according to the Führer principle . Above all, she lived from negative statements: she was against democracy, against the Versailles Treaty, against the capitalist economy and against other races as well as the Jews. The NSDAP experienced its successes in each of the crises of the Weimar Republic (hyperinflation until 1924 and especially the global economic crisis since 1929).

After Hitler's unsuccessful coup attempt in 1923, he tried, despite all the radicalism of his policy, to give it a legal look. He benefited from the economic crisis that began in 1929 and, in particular, from attempts by conservative politicians to make the state more authoritarian. These politicians, which included Chancellor Heinrich Brüning , Kurt von Schleicher and, for the longest and most vehemently, Franz von Papen , believed that they could use Hitler for their purposes, which is why the NSDAP was not banned. In January 1933 a coalition government of NSDAP and DNVP came about.

In a few months, Hitler consolidated his dictatorship. In the course of the Gleichschaltung , the parties (except for the NSDAP) were either banned or dissolved. The SPD was banned on June 22, 1933, the DNVP and DVP disbanded on June 27, and the BVP on July 4. On July 14, the law against the formation of new parties came into force. The KPD and SPD had organizations in exile (the latter called itself Sopade ).

The NSDAP was originally supposed to be a cadre party that selects its members and trains them ideologically. When a freeze on admission was imposed on May 1, 1933 , 1.6 million new members had already been admitted since the seizure of power, the former members only made up a third of the total membership. The new should endure a two-year probationary period without a party book and brown shirt. Until it was completely repealed in 1939, Hitler relaxed the admission freeze in order, among other things, to involve the elites in the state and society. The party should take hold of the nation and exercise control. At the end of the war it had six million members. Far more people were connected to the NSDAP through various sub and subsidiary organizations.

The party was of little importance in the ruling apparatus. Their seat remained in Munich, and Hitler had appointed Rudolf Hess , who had no house power, as his deputy in the party . He also prevented large party meetings, for example on the model of the Great Fascist Council in Italy. The law to secure the unity of party and state of December 1, 1933 made the NSDAP a corporation under public law, so it could be financed by the state. Hess and SA chief Ernst Röhm became Reich ministers in their party characteristics. The result was officially an upgrading of the party, but ultimately also its inclusion and subordination in the total state.

German division 1945–1990

Since the occupation by the four victorious powers, the remaining Germany was divided into four zones in 1945 . The rebuilding of parties took place first at the local level and then within the zones. Apart from the fact that the Germans were not allowed to freely cross the zone borders, one party (until 1950) had to have a license from the respective occupying power. Organizations of refugees and displaced persons as well as the NSDAP and any successor organizations to these were banned.

Former NSDAP members were accepted into all parties. This was and is viewed critically, on the one hand, as a moral burden on the parties, on the other hand, as a positive reintegration of this large number of people and winning over to democracy. Critical political influence in the sense of infiltration only existed in the case of the FDP, especially in the 1950s in North Rhine-Westphalia ( Naumann district ). Even the British occupying forces intervened there in 1953.

Only four parties were allowed in all four zones: the Communist Party of Germany , the Social Democratic Party of Germany , the Christian Democratic Union (as a bourgeois Christian collection) and the Liberals, who often had different names in the individual countries (ultimately sat in the West the name Free Democratic Party through). Essentially, the parties were built by people who had political experience prior to 1933. Despite the decisive events before, during and after the war, according to Lösche, structures and traditions continued to have an effect. The eastern areas, strongholds of the conservatives, were lost, however.

Parties in the Soviet Zone of Occupation

The Soviet occupying power was the first to allow political parties as early as June 1945. The Soviet Union hoped to give the parties in its zone a head start over those in other zones and that the headquarters in Berlin-Mitte (in the eastern part of the city) would be recognized as pan-German centers. The military administration SMAD wanted to work together with the other opponents of Hitler, according to Hermann Weber, but only the German communists were ready to unconditionally submit to Stalin's policy. The SMAD promoted the communists by placing them in decisive positions in the administration. The KPD was the first to be founded on June 11, 1945, followed in June / July by the SPD, the CDU , the liberal LDPD and in 1948 the NDPD .

The KPD initially presented itself as a moderate force that wanted to make Germany anti-fascist and build a parliamentary-democratic republic. The actual goal of the KPD leadership around Walter Ulbricht , who had returned from exile in Moscow, remained the establishment of a dictatorship based on the Soviet model. It was known that the population was strongly anti-Soviet, so Stalin and the KPD spoke of their own national paths to socialism .

While there were initially forces in the SPD and KPD who wanted to unite both parties, the SMAD first wanted to completely Stalinize the KPD . In the course of 1945 the willingness of the SPD to unite cooled significantly after experiencing the reprisals of the SMAD. Finally, in April 1946, the Social Democrats were forced into a party with the Communists, the SED .

By 1948 at the latest, the SED was completely dominated by the communists. For some time a “kind of hymn of the SED” was the “ Song of the Party ”, which was composed for the 1950 party congress. According to Malycha and Winters, it reflects the mood and aspirations of the SED:

“She gave us everything / bricks to build and the big plan. […] / The party, the party, is always right! [...] So, out of Lenin's spirit, / Growing, welded by Stalin, / The party - the party, the party. "

In the state elections in October 1946 in the Soviet Zone , however, the SED did not yet have the resounding success that the Soviet Union had expected. In order to weaken the bourgeois parties CDU and LDPD, the SMAD founded the Democratic Peasant Party of Germany (DBD) and the National Democratic Party of Germany (NDPD) in 1948 , which were completely under the control of the SED.

In addition, SMAD and SED secured power by removing the leadership of the CDU and LDPD or forcing them to take a pro-communist course and only “unit lists” of the bloc (later the National Front ) were “eligible” for elections . Since all parties ran for candidates on a single list, it was determined in advance which party received how many seats. The constitution of the GDR, founded in 1949, explicitly secured the SED's claim to leadership since 1968.

Western zones and establishment of the Federal Republic

In the western occupation zones , the parties were admitted a little later than in the Soviet occupation zone . On August 6, 1945, the military government of the British zone of occupation announced its general willingness to approve German parties. Parties quickly formed at the state level, and the CDU joined forces on February 5, 1946 at the zone level. In addition to this, as well as the SPD, FDP and KPD, the Lower Saxony state party (later the German party ) and the center received approval.

The American occupying power has allowed parties at the district level in its zone since September 1945. In the previous month there had been SPD state boards in Hesse and Württemberg. In addition to the four parties permitted in all zones, the Bavarian Party and the Economic Development Association in Bavaria also received the license.

In the French occupation zone , the parties did not receive permission to organize themselves nationally until 1946 (Rhineland in January, Baden and Palatinate in February, Württemberg in March). The names of the parties were initially not allowed to contain the word Germany; the Social Democratic Party was not able to add the word until November. In the Saarland there was a special development because France did not allow later integration into the Federal Republic until 1955, but comparable parties were formed there too. However, the Saarland parties had to follow the course of the occupying power, which wanted to separate the Saarland from Germany. Only in the state elections in 1955 were pro-German parties allowed to participate.

With the merging of the zones of occupation (American-British bizone since 1947), the parties were also able to work together more closely across zones. The constitution of the new western state, the Basic Law of May 1949, mentioned the parties positively as helping to shape political opinion. This recognized a longer-term development in line with the actual importance of parties in modern states. (In other European countries, too, this constitutional recognition only took place after 1945.)

The Social Democrats, under the leadership of their foreman Kurt Schumacher, who lived in Hanover, opposed the incorporation by the Communists; The latter lost massive votes in the early 1950s. Schumacher wanted to expand the basis of the Workers' Party SPD, but ultimately thought in terms of class struggle:

“ The class of industrial workers is, in the true sense, the power of the SPD. As a whole class, it must be gathered around the idea of democracy. Without the workers, social democracy cannot take a step.

Of course, there will only be decisive success if this platform succeeds in attracting the medium-sized masses. [...] The excessive and chunky simplification of the class struggle idea, the formula class against class, in its primitive undifferentiation bypasses the real forces and is effectively a reactionary slogan. […] The small owner does not belong to the defenders of property, but to the side of the dispossessed. [...] As long as large fortunes can arise in Germany in the hands of irresponsible private individuals, they will keep trying to turn their economic power into political influence. "

The Christian Democratic Union was able to establish itself in almost all countries as a broad collection of Christians, conservatives, nationally conscious, but also liberals, and since 1950 as a federal party. In Bavaria there was an independent party called the CSU, which has since formed a joint parliamentary group with the CDU at federal level. The Christian Democrats interpreted National Socialism as a consequence of turning away from Christian values:

“None of this would have come over us if large parts of our people had not been guided by greedy materialism. [...] Without moral support of their own, they succumbed to racial arrogance and a National Socialist intoxication. The megalomania of National Socialism was combined with the ambitious lust for power of militarism and the big capitalist armaments magnates. [...] What alone can save us in this hour of need is an honest reflection on the Christian and occidental life values that once ruled the German people and made them great and respected among the peoples of Europe. "

In 1947/1948 the Liberals tried in vain to set up an all-German party. However, the Democratic Party of Germany with two chairmen, Theodor Heuss and Wilhelm Külz , failed because of the East-West conflict. Then the Free Democratic Party was founded in the western zones. It should unite both left and right liberals; depending on the regional association, however, one or the other direction dominated.

Initial diversity in the Federal Republic of Germany until 1961

In the first federal election in September 1949, ten parties and three independents made it into the Bundestag (CDU and CSU, the “Union”, counted as one party). In addition to the roughly equal parties CDU / CSU and SPD, the liberal FDP and the communist KPD were also active throughout Germany. The latter lost its parliamentary group status after the communist MP Kurt Müller did not return from a trip to the GDR and the Bundestag administration did not accept his written waiver of his mandate. Due to the connection to the GDR leadership, the KPD was discredited and politically insignificant.

The other parties in the first Bundestag had each achieved less than five percent. But you could still send representatives to parliament because the five percent hurdle was only applied per federal state at the time . Indeed, practically or by their orientation, they were regional parties. In the north, the conservative German party was active, which had its home country in Lower Saxony, but was also represented in the state parliaments of Schleswig-Holstein and Bremen. Also from the north came the German Conservative Party - German Right Party , which continued right-wing conservative and right-wing radical ideas from the Weimar Republic. The South Schleswig voters' association represented the Danish and Frisian minorities. The center owes its mandates to votes from North Rhine-Westphalia. In Bavaria, the Economic Development Association and the Bavarian Party had jumped the five percent hurdle, both conservative, medium-sized parties, the former more urban, the latter more rural.

The five percent hurdle was tightened until the second federal election in 1953. From then on, a party had to unite at least five percent of the votes nationwide. Another alternative was that one electoral district mandate was sufficient to overcome the hurdle; since 1957 there have to be at least three. This contributed to the fact that the number of Bundestag parties decreased.

In 1950, the end of the license requirement made it easier to found new parties. The most important re-establishment of this time was the All-German Bloc / Federation of Displaced Persons and Disenfranchised (BHE) as a representative of the displaced and refugees. In Schleswig-Holstein, half of whose population consisted of refugees, he even achieved 25 percent in state elections.

In 1952, the federal government applied for bans on political parties for the first time, namely the right-wing extremist Socialist Reich Party , which was banned that same year, and the KPD, which was banned in 1956. The Federal Constitutional Court , created in 1951, pronounces the actual ban on parties if the party endangers the constitutional order of the Federal Republic. Organizations that have not achieved the status of a party can more easily be banned under association law. In 1993, for example, a ban was filed against the Freedom German Workers' Party , but two years later the constitutional court ruled that it was insufficiently organized for one party. The Federal Ministry of the Interior then issued the ban. A non-banned party is not necessarily constitutional, because the state can waive an application if it considers the party to be politically ineffective or, in the event of a ban, fears that it will continue to work underground (which is more difficult to control).

In the federal election in 1953, the governing parties CDU / CSU, FDP and DP as well as the SPD and, for the first time, the BHE came into parliament. Although Konrad Adenauer's Union had received half of all mandates, he entered into a coalition with the other parties except the SPD. In doing so, he incorporated possible bourgeois opposition parties and on top of that came up with a two-thirds majority. As early as 1955, the BHE left the government because it saw the Saar Statute as a precedent for the eastern territories (the statute promised the separation of the Saar region under the European flag). The two BHE ministers who joined the CDU remained in the government. A year later, the greater part of the FDP followed in the opposition, back in the government remained the "ministerial wing", which founded the unsuccessful Free People's Party . It was very similar with the DP, whose ministers were transferred to the CDU in 1960.

Initially, the parties financed themselves through membership fees and donations, the SPD primarily through contributions and contributions from members, and the bourgeois parties through donations from industry. An amendment to the Income and Corporations Act 1954 favored party donations for tax purposes, and a lot of money from the economy benefited the bourgeois parties. The Federal Constitutional Court forbade this in 1958 because the opportunities for parties with close ties to the capital were increased. But it suggested that the state could provide funding to the parties.

Tripartite system from 1961 to 1983

For the first time, only CDU / CSU, SPD and FDP were elected to the Bundestag in 1961. In the federal states, too, other parties were rarely successful. It was above all the CDU / CSU that absorbed the small bourgeois parties with the exception of the FDP. The SPD, on the other hand, did not move towards the center until 1959 with the Godesberg program , recognized its ties to the West in 1960 and now increasingly addressed voters who were affiliated with the church.

In the 1960s there were all three possible coalition constellations, so all parties were able to form a coalition with one another. Back then and in the 1970s, the CDU / CSU was usually not very far from the absolute majority. Together with the FDP, which was normally good for six to ten percent, a Christian-liberal coalition could easily be formed. The SPD was several percentage points behind the CDU / CSU (with the exception of 1972), so that a social-liberal coalition with the FDP had a much smaller majority.

The most successful party outside the Bundestag at the time was the right-wing extremist National Democratic Party of Germany , which had moved into most of the state parliaments since 1966. In 1969 it failed with just under 4.3 percent in the federal election and left all state parliaments after only one legislative period. In later years it faced competition from other right-wing extremist parties, but was still able to move into a state parliament in Saxony on September 19, 2004 with 9.2 percent of the vote. On the extreme left, the German Communist Party (DKP), founded in 1968 , actually a re-establishment of the KPD, had the highest number of votes, but mostly remained below one percent. Communist splinter groups of the 1970s, the K groups, were even more unsuccessful .

In connection with the federal election in 1976, there was a dispute within the Union. CDU leader Helmut Kohl wanted to replace the SPD-FDP coalition that had ruled since 1969 by winning the FDP through a moderate union course. The CSU under Franz Josef Strauss, on the other hand, devised the Fourth Party's strategy : the right-wing CSU should expand to the federal territory in order to mobilize the right-wing voter potential more strongly. The CDU could then better address the voters in the middle. However, the CDU prevented the concept by threatening to found a CDU regional association in Bavaria. Opponents of the concept feared that friction between both parties would have caused more damage to the Union overall.

In the period after Adenauer and during the social-liberal coalition, the FDP was able to assert itself despite or thanks to coalition breaks and coalition changes. The election of Walter Scheel as party chairman in 1968 brought her a bit far away from the rather national liberal course of her predecessor Erich Mende . Around 1970 social liberalism had a certain flowering phase with the Freiburg Theses of 1971. In 1979, however, the FDP again emphasized economic liberalism with the Kiel theses .

The two coalition changes in 1969 and 1982 were sometimes associated with considerable problems for the Free Democrats. After the Bundestag elections in 1969, the National Liberal Action was formed on the right and, after the turnaround in Bonn in 1982, the Liberal Democrats party formed on the left ; neither could gain any appreciable support. Changes from the FDP to other established parties were more important: in 1970, for example, the former party chairman Mende joined the CDU, in 1982 the general secretary Günter Verheugen and the chairwoman of the finance committee of the German Bundestag, Ingrid Matthäus-Maier, joined the SPD.

In 1958, the Federal Constitutional Court prohibited donations to one party from receiving tax benefits. This temporarily put the CDU and FDP in need. Since then, the federal budget has at least provided money for political education work; since 1963 this has been expanded and increased. In July 1966, however, the Federal Constitutional Court ruled that only the election campaigns could be co-financed from state funds, but not all party work. Already in the following year, the parties realized the announced already in the Basic Law, but long out-delayed law on political parties . It also contained rules on party funding. The parties found many ways to get money, according to Peter Lösche, including in violation of party law. The result was scandals like the Flick affair . Since 1984 there have been further rules, for example on the obligation of a party to disclose the origin of its funds.

Broadening the spectrum of parties from 1983 to 1990

At the end of the 1970s, a new type of political grouping succeeded in moving into state parliaments. It was called the Green List or Green List Environmental Protection and was founded in 1980 at the federal level under the name Die Grünen . At first it united both left and right supporters of environmental protection until the latter left the party under Herbert Gruhl . In addition, former members of the K groups were active in the Greens, but last but not least, the party mobilized those who were previously unaffiliated. In 1983 and 1987 she came to the Bundestag. As early as 1985 the Greens were (briefly) involved in the Hessian state government.

The Greens stood for a revival of the anti-party affect and not only used unusual terms for party organs (such as “speaker” instead of “chairman”). The vigor as a movement should be preserved by preventing a party elite. Members of the Bundestag should only earn as much as workers and only keep their mandate for two years, top positions were filled as a duo and for the committees, at least fifty percent of the relatives had to be women. Little by little, many of these provisions were relaxed again, and the party also began to make a name for itself outside of the issue of environmental protection. Other new topics of this party were, for example, data protection on the occasion of the protests against the census in 1983 and 1987, the peace movement and the anti-nuclear movement .

The election successes of the Republicans (REP), a right-wing conservative to right-wing populist party founded in Bavaria in 1983, were similarly sensational . For the first time since the NPD in the 1960s, a party to the right of the Union managed to get back into a state parliament: In January 1989 it jumped to 7.5 percent in West Berlin, and in June to a little less in the European elections . In the years that followed, the Republicans and right-wing extremists from the NPD and the German People's Union (DVU) made it to other state parliaments, but were usually only able to remain in them for one legislative period and failed in Bundestag and European elections because of the five percent hurdle.

Parties in the GDR

In addition to the SED and the bloc parties CDU, LDPD, NDPD and DBD, so-called mass organizations also had representatives in the GDR People's Chamber, for example the trade union federation FDGB . These MPs were usually SED members, so the SED was far more represented in the People's Chamber than the strength of the SED faction suggests (127 of 500 MPs at the end of the GDR). However, all other members of the SED had to follow suit. It was not until the late 1980s that some cautiously dared to criticize the SED policy, substantially only after the fall of the Berlin Wall in November 1989.

For some GDR citizens, the idea of being able to belong to someone other than the SED was attractive. At least in the CDU and LDPD, some did not want communism to be the goal of history, said Peter Joachim Rapp. These parties could be viewed as a home by Christians or the self-employed. The NDPD and DBD, on the other hand, lost the social classes for which they were founded, as there were fewer and fewer old National Socialists and individual farmers. It was in the interest of the SED to create the impression that these parties had limited autonomy. The block parties had their integration and transmission function (the integration of non-socialists in the dictatorship) until 1989. In their statutes they had to recognize the leading role of the SED, and since this was even enshrined in the GDR constitution, the block parties remained the alibi function (to pretend a multi-party system) questionable. The function of the whole of Germany was also undermined because they hardly made any contacts with the West.

When the SED was founded in 1946, the membership cards were taken over by the SPD and KPD. In April 1947 the SED had 1,766,198 members, 33.6 percent more than a year earlier when it was founded. After a short-term increase, the number has fallen since 1948, on the one hand due to death, resignation or exclusion, and on the other hand due to write-offs of SPD members who were no longer active after the forced unification. In December 1949 there were 1,603,754 SED members.

That year the party introduced the status of candidate, which had to prove himself two years before being accepted. The aim was to prevent uncontrolled growth and to influence the political and social composition of the party. In December 1952, membership reached its lowest point, 1,225,292. By 1988 the number of members rose to 2,324,775, just below the high of the previous year. In the course of 1989, over three hundred thousand members left the SED until the great wave of resignation began in mid-November. By the end of January 1990, 907,480 members had left the party.

While in 1989 every fourth adult GDR citizen belonged to the SED, only every twenty-fifth was in one of the four bloc parties. In September 1989 they had a total of 491,000 members, of which the CDU was the largest with 141,000. They have certainly gained members since the 1970s and 1980s. After November 1989, their membership also fell, most notably in the NPDP from 112,000 in September 1989 to around 50,000 in March 1990.

Reunification and unified Germany since 1989/1990

The social and political dissatisfaction in the GDR led to public protests and a mass exodus, which has been easier via other countries since the summer of 1989. When, on November 9, 1989, an unsuccessful press conference resulted in countless GDR residents wanting to visit the West and rushing to the border crossings, the SED gave up its dictatorship.