Suffrage in the North German Confederation and in the German Empire

The right to vote in the North German Confederation and the German Empire came about with the establishment of the North German Confederation in 1867 and the establishment of a Reichstag as parliament. In 1869 the federal government passed a federal electoral law , which was applied for the first time to the Reichstag election of March 1871. This choice is already part of the history of the German Empire, which has existed since 1871 .

The generality and equality of elections were rather rare in a global comparison, so that the right to vote can be considered to be extremely progressive. In addition, the elections were direct, i.e. the MPs were elected directly without the detour via electors (as in the American presidential elections or as in the Prussian three-class suffrage).

In principle, all men over 25 years of age were allowed to vote in the North German Confederation and in the German Empire, each with one vote. Groups that were excluded in many other countries at the time were excluded, such as men who lived on poor relief. The voters selected a direct candidate in their constituency; if no candidate reached an absolute majority, there was a runoff election. The election was supposed to be secret, but it took a long time before measures were taken so that only the voters concerned knew who they were voting for.

As early as the First World War (1914–1918), the discussion of reforming the electoral law made considerable progress. In the aftermath of the November Revolution of 1918, all constitutions and electoral laws were renewed at the national and state levels: under the Weimar Republic suffrage , women were also allowed to vote , the voting age was lowered, and the Reichstag and state parliaments were elected according to the principle of proportional representation.

Prussia's advocacy of universal suffrage

The general right to vote (for men, regardless of skin color, class and religion) in the North German Confederation was very progressive for its time. In Europe it could be compared with that in Switzerland and the Third French Republic, as well as the right to vote in Greece. A similar number of men were not allowed to vote in Spain until 1890, in Norway in 1906, in Austria, Finland, Sweden and Italy in the years up to the First World War, in the Netherlands since 1918. In the USA they stayed until well into the 20th century, especially in the southern states , African Americans and, in some cases, people affected by poverty are excluded from voting and political life. In Great Britain the right to vote was extended in 1867 but remained severely limited for men too; it was not until 1949 that the last special votes for the wealthy and nobles were abolished.

The universal male suffrage in Germany was won neither by the popular masses nor by socialists or bourgeois democrats, but (much like other countries, for example in the USA or France) by the elite. Therefore, the research has concentrated more on Otto von Bismarck , who had been Prussian Prime Minister since September 1862. For him, this right to vote was a foreign policy argument against Austria. In addition, one could legitimize the Prussian expansion of power through an appeal to the nation. After all, Bismarck did not want to strengthen parliament, but rather weaken it, as Thomas Nipperdey wrote.

At the national level, Prussia opposed Austrian plans in 1862/1863 to set up a new form of delegate assembly in the German Confederation . Instead, Prussia demanded a directly elected representative body. On April 9, 1866, Prussia even spoke out in favor of universal suffrage in the German Confederation, albeit without mentioning equality of election. On June 10, Bismarck explicitly referred to the Frankfurt election law of 1849 in his proposal for a new German federal constitution . After winning the war against Austria it was also mentioned in the August treaties for the new (northern German) federal state .

Whether Bismarck really believed that universal suffrage would serve the conservative cause cannot be generally determined. Bismarck may have followed his convictions about Prussia, but at the national level he presented universal suffrage for tactical reasons. After Bismarck had specifically committed himself to the Frankfurt electoral law in the summer of 1866, and after the Prussian king had given his approval, there was no turning back. The two North German Reichstag elections of 1867 should then, to the delight of Bismarck, actually end with a conservative-liberal majority. But the Pomeranian nobleman Alexander von Below immediately warned the Prussian Prime Minister that a battle at Königgrätz (the decisive, popular victory against Austria in 1866) could not be fought before every election .

The liberal Progressive Party and the German National Association also invoked the Frankfurt Imperial Constitution and its electoral law of 1849 . This enabled the national movement, firstly, to underline its independent position independent of the Prussian government, secondly, to position itself vis-à-vis Austria and a mere federal reform, and, thirdly, to involve the democratic left (the left had at the time ensured that universal suffrage was included in the electoral law in Frankfurt came). Biefang: "The appeal to the imperial constitution and electoral law should bring the diverging currents and interests to a common denominator, it served 'nation-building'."

North German Confederation 1867–1870

After the northern German states left the German Confederation and after the German-German War in June / July 1866, the northern German states wanted to unite to form a new league. Due to the alliance treaty of August 1866 , a (north German) Reichstag was to become the common parliament. The constitution should be agreed between:

- on the one hand the governments of the individual states, corresponding to the prince in a single state,

- and on the other hand the popularly elected Reichstag.

Since there was initially no north German state, there could also be no uniform federal electoral law. The individual states concerned put electoral laws into force in their areas with the same wording, each individually. As agreed, the Reich election law of April 12, 1849 served as a model.

The respective electoral law required the approval of the state parliament of the individual state concerned. There was considerable resistance in the Prussian House of Representatives , because the liberal Progressive Party was disturbed by the planned federalism of the draft constitution. Since Prussia is so preponderant in the North German Confederation (eighty percent of all residents), it is sufficient for the other states to elect members of the Prussian House of Representatives. Right-wing liberal and conservative MPs were against equal voting . In addition, the progressors believed that the final decision on the North German constitution must lie with the parliaments of the individual states. The House of Representatives therefore changed the electoral law by a large majority, so that the constituent Reichstag only deliberates on the North German constitution . The Prussian king put the electoral law into effect on October 15, 1866, similar to the other individual states concerned.

The Prussian electoral law for the constituent Reichstag of the North German Confederation of October 15, 1866 stipulated that one member was elected for every 100,000 inhabitants. Men who met all of these criteria were allowed to vote:

- at least 25 years old,

- Citizenship in one of the federal states for at least three years,

- Impunity, which currently means full enjoyment of civil rights, without prejudice to sentences served

- not under guardianship or trustee , no bankruptcy proceedings

- no receipt of poor relief by the public or the community at least one year before the election,

- Residence in the place of election,

- Entry in the election lists.

The electoral law spoke of a direct election with an absolute majority in a single constituency; if necessary, the winner was to be determined in a runoff election among the top two. You voted with a concealed ballot without a signature. The electoral law was essentially similar to the right to vote in the German Empire.

The elections for the constituent Reichstag took place on February 12, 1867, in 297 constituencies with one or two ballots. 235 of them were in Prussia, 23 in Saxony. Since 1848/1849 this was the first choice in Germany, which affected several individual states.

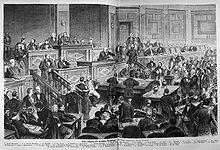

Discussion in the constituent Reichstag in 1867

In March 1867, the constituent Reichstag deliberated on the right to vote, with only a few speakers still speaking against the generality of the election. However, the Liberals made their at least fundamental discomfort with the general public clear, even though they agreed to it in the given case. The liberals succeeded in enforcing voting secrecy, which was by no means a matter of course in the 19th century.

Another issue was the question of whether the Prussian government or the North German Chancellor should put up official candidates for the elections. This was in France at that time of the authoritarian ruling Napoleon III. common. At the time of the constitutional conflict in Prussia from 1862-1867 there was even a plan to simply count non-voters as voters for the government candidates. But after the victory at Königgrätz against Austria, when Bismarck's prestige was at its height, such manipulations were no longer up for discussion. Ultimately, the proponents were in favor of supporting “German” candidates for unity in areas with national minorities, or where the conservative parties had no organization.

Bismarck realized that through government candidates he might get a more right-wing, more conservative Reichstag than would have served his federal constitution. There were also risks if the government interfered in the election campaign. The election itself would then degenerate into an election for or against the government, which would encourage the idea of parliamentary government. A defeat of the government candidates would mean a loss of authority. Voters could even vote for the opposition out of outrage about government candidates. And anyway, the voters would also know which candidates were in the interests of the government, and the district administrators would have the official apparatus at their disposal anyway.

Finally, the question of MPs' diets was controversial. Bismarck was fundamentally against it, in return he accepted that civil servants could be elected. Traditionally, the Conservatives, and with them Bismarck, believed that politically active officials spearheaded the opposition. But it turned out that there were many government-friendly MPs who were civil servants. For their part, the Liberals did not want any discussion directed against the eligibility of civil servants. They were afraid that judges or teachers, but not (more conservative) district administrators or officers, would be excluded from eligibility.

North German Federal Constitution and Zollverein

In the constitution of the North German Confederation of August 2, 1867, it was finally stated:

"The Reichstag is the result of general and direct elections with secret ballot, which have to take place until a Reich election law is passed in accordance with the law on the basis of which the first Reichstag of the North German Confederation was elected."

The first ordinary Reichstag was elected on August 31st. According to the constitution, both the Reichstag and the Bundesrat could propose a law. Both bodies had to approve the proposal for the law to come into effect. The Federal Council was the representative of the member states in which electoral law was usually unequal.

The question remained as to how the southern German states could be brought closer to the North German Confederation or even join it. On July 8, 1867, the Zollverein was put on a new basis. In customs and trade issues, the individual states were no longer sovereign, but the Zollverein. Most of the German states (with the exception of Austria) were represented under Prussian rule. A customs parliament served as a representative body on the basis of general, equal and direct suffrage. Therefore, in 1868, several South German members were elected to the already existing North German Reichstag. Since mostly MPs were elected who were skeptical of the Prussian expansion of power, Bismarck did not pursue his intention to use the customs parliament as a basis for a further unification process.

Reichstag elections under the Election Act of 1869

Without general suffrage: no general suffrage General unequal suffrage: with public indirect suffrage with indirect secret ballot with direct secret ballot General equal suffrage: with indirect election only for payers of direct taxes with second vote for elders without Restrictions on the right to vote in neighboring countries: blue: limited right to vote, e.g. B. Belgium , red: universal equal voting rights, e.g. B. France .

On May 13, 1869, there was a separate law for the Reichstag election, the election law for the Reichstag of the North German Confederation . The Social Democrat August Bebel moved that men should also vote who received public poor relief. This was rejected by a large majority. The federal electoral law differed slightly from the previous electoral law.

According to Art. 18, the law was to come into force at the next election of the Reichstag, replacing the previous Reichstag election laws (which had been enacted at the level of the individual states). There was no renewed election during the time of the North German Confederation. The Reichstag was elected on August 31, 1867 and, according to the constitution, the legislative period lasted three years. But after the French declaration of war on July 19, 1870, the Reichstag decided on July 21 that the Reichstag would not be re-elected during the war.

In November 1870, the southern German states of Bavaria, Württemberg, Baden and Hessen-Darmstadt signed the November Treaties to join the federal government. On January 1, 1871, the constitution of the German Confederation, known as the German Reich, came into force. In Art. 80, I. 13, it listed those laws of the North German Confederation which it declared to be laws of the state enlarged to include southern Germany. This also included the federal election law. (This article is missing in the revised constitution of April 16, 1871.) On March 3, 1871, the first Reichstag of the German Empire and thus the first Reichstag was elected under the law of 1869, with the new constituencies from southern Germany. In 1873 the constituencies of Alsace-Lorraine , annexed in 1871, were added.

There were also implementing provisions for the electoral law in a regulation dated May 31, 1869. Among other things, it deals with keeping the electoral roll, the division of the electoral districts and which organs in the individual states are responsible for this. According to the constitution, the Reichstag elections took place every three years, from 1888 after a constitutional amendment every five years. Only the Kaiser was allowed to dissolve the Reichstag and call new elections with the consent of the Bundesrat. In practice, the decision came from the Chancellor.

Parties

In the course of time it was hardly possible for a candidate to be elected without the active support of a party. An organization like the church or the farmers' association may have provided this help. Parties were not mentioned in the imperial constitution. The Reichstag Election Act of 1869, however, stated (Section 17):

"Those entitled to vote have the right to form associations for the operation of electoral matters affecting the Reichstag and to hold unarmed public meetings in closed rooms."

Strictly speaking, the named associations are to be distinguished from the parties as electoral associations; they were a kind of auxiliary organs, extended arms of the political parties . According to Ernst Rudolf Huber, the legislature wanted to guarantee the parties a certain public law status : until 1866, parties were still banned in the German Confederation. But the electoral law “presupposed the existence and effectiveness of political parties”, since without them the holding of free elections and a national parliament were impossible. The Reichstag therefore did not want to leave the decision on the existence of parties to the law of the federal states. The protection of the electoral associations was directed not only against the regional authorities, which only partially and in simple laws protected associations, but also against the executive at the national level.

A Social Democrat could also be a candidate and be elected, while his party was banned during the Socialist Laws (1878–1890). She even won unexpected votes back then. One MP enjoyed parliamentary immunity ; the majority in the Reichstag was usually on the side of an attacked person and granted him the suspension of prosecution. What a member of the Reichstag said was protected by the constitution.

If a new election was announced in the Reichstag, the official election period began. Through an addition of 1883 in the electoral law, political print products also enjoyed the freedom of election time, so that the measures of the socialist law had even less effect. The election period usually lasted about four weeks, with a runoff election six. In addition, there were between 25 and fifty by-elections per legislative period.

Electoral meetings

Election meetings had to be registered, for example in Prussia at least 24 hours in advance with the local police. Often times, the police tried to refuse registration on some pretext. The Reich Association Act abolished the registration requirement in 1908, and open-air meetings still had to be approved.

Depending on the state, the police could closely guard an election meeting and disband it for vain reasons. In 1884, for example, the change in the intended speaker led to a ban on a meeting in Saxony, while in Bavaria a police officer was only allowed to attend an election meeting as a guest without official activity. The possibilities of police interventions were finally limited nationwide in the Reich Association Act.

Women were excluded from political meetings in Prussia and Saxony (and initially in other states); their presence could cause the police officer present to end the meeting. In later times, however, the handling was no longer very strict, since conservative assemblies also allowed women. These had to be separated from the men by a string or chalk line, but there was also the Social Democrat Lily Braun , who gave speeches to audiences that were often thirty percent women and had no barriers. The law of association and assembly in 1908 ended the restrictions on women. Women did not get the right to vote until the November Revolution.

General and equal choice

From 1869 onwards, all residents were allowed to vote and thus exercise their right to vote

- were male,

- were at least 25 years old,

- were citizens of one of the states

- resided in one of the constituencies,

- were not active soldiers

- were no prisoners,

- did not live on poor relief,

- were not incapacitated.

While in 1874 11.5 percent of male Germans of voting age were excluded from voting, this was the case for 5.9 percent in 1912. This was due to the fact that the electoral lists were kept better and the criteria were interpreted differently (in the Weimar Republic it was only two percent). Citizens who lived abroad or in the German colonies could not vote because they did not live in an electoral district. There was an administration within the colonies, but no representative bodies.

According to the electoral law, an eligible voter had the subjective right to vote. Nevertheless, many constitutional law teachers at the time believed that it was only a matter of the reflex of an objective law. The voter exercises a public function, a responsible office. In doing so, they wanted to emphasize the common good , the public interest in the undisturbed exercise of voting as well as an obligation to vote and protect the right to vote with laws, for example against buying votes or being forced to vote. But freedom of choice also includes the right not to vote. It was also the purpose of the electoral act that only votes were cast out of free conviction (and not invalid ones, just to satisfy compulsory voting). Considerations to introduce compulsory voting were opposed to a high voter turnout , which increased during the imperial period. It demonstrated the political sense of responsibility and the inner participation of the citizens, if this was possible without compulsory voting.

The voting age remained unchanged until 1918, although it was sometimes mentally tied to the age of majority . On January 1, 1876, this was set uniformly for 21 years in the empire. The SPD wanted to lower the voting age from 25 to 20 years, and in March 1917 the left-wing USPD submitted an application supported by the SPD. The reduction was associated with military service, whereupon the opponents (left-wing liberals , national liberals , center ) replied that the voting age would then have to be lower because otherwise the younger soldiers would be treated unequally. Furthermore, military service does not automatically bring political maturity with it. In the November Revolution of 1918, the SPD and USPD then set the voting age at 20 years.

DC was the former option because each voter the same number of votes had (a) and every vote count had the same. Nevertheless, the votes in the majority electoral system of that time did not necessarily have the same success value: Whoever gave his vote to a defeated constituency applicant, his vote was no longer considered. This circumstance was then also an argument in the discussion about proportional representation, because there is not only a formal, but also a material electoral equality.

Whoever had the right to vote was eligible. There were also soldiers, while members of the Federal Council were excluded from the right to stand for election. If an elected official became a public official, he had to give up his mandate. Someone was allowed to run in several constituencies, but only accept one mandate. The sovereign rulers (such as the Prussian King or the Baden Grand Duke) were not expressly excluded from eligibility, but since one was not allowed to belong to the Reichstag and the Bundesrat at the same time (Art. 9 of the Constitution), it can be assumed that a sovereign was not either Was allowed to be a member of the Reichstag, as this officially instructed the votes of his state in the Federal Council. In the October reforms of October 28, 1918, Article 9 was not removed, but the amendment to Article 21 meant that the members of the Reichstag did not lose their mandates when they entered the government.

Until 1906 there were no diets , i.e. no remuneration for the parliamentary mandate. Diets were well known in Germany at the level of the individual states, but Bismarck had spoken out in favor of a ban in the imperial constitution - as a compensation for universal suffrage. It cost around 6,000 marks to maintain a second residence in the capital Berlin and not be able to pursue a bread-and-butter job for eight months of the year. With that, practically 99 percent of the people were excluded. For many less well-off people, it was only possible to exercise their mandate if their party helped them out, for example by hiring a member of parliament as editor of a party newspaper. This tied them more closely to the party; the SPD was the model for other parties. Bismarck wanted to prevent the development of a class of professional politicians, but in this way they had to turn politics into a profession. While party support was viewed as disreputable in England, it was socially accepted in Germany precisely because the constitution indirectly forced politicians to do so.

Execution of choice

Election workers

The north German Reichstag faced the problem that holding elections required a large number of helpers. The government suggested that officials should always sit on the electoral bodies, while the members of the Reichstag believed that the people should hold their own elections. Ultimately, the rule was that the state authorities were responsible for appointing the chairpersons of the electoral boards . This was usually the mayor or district administrator , or their counterparts outside Prussia.

The chairman of the electoral board appointed a secretary and three to six assessors , who could not be state officials. In the individual states there was heated argument about who was considered a civil servant : government councilors and police officers were excluded, teachers or village chiefs were mostly not, although they were usually not elected but appointed. Formally, they could be viewed as local, not state, officials. Finding suitable people was difficult, and the chairpersons also looked primarily for politically like-minded people. The composition and familiarity of electoral boards with the rules was often part of the election challenges.

place and time

The polling stations should be open between 10 a.m. and 6 p.m. (from 1903 until 7 p.m.). By deviating from this, electoral boards were able to prevent unpopular voters from casting their votes. In Bamberg, for example, a left-wing liberal did not open the polling station until 4 p.m. because the conservative farmers wanted to go to the far-away agricultural fair the next morning and therefore had to leave the village early.

Last but not least, the selection of a suitable polling station could be controversial. When an arrogant teacher in the Rosenheim district only opened his schoolhouse to voters at will, an angry citizen said that the mayor's apartment was better suited for everyone to vote without being forced to. In rural areas in particular, voting was often done in the home or factory of a respected citizen, and even in larger cities not only in schools, hospitals or town halls, but also in hotels and restaurants. This could lead to confusion about the authority of the owner, or to the fact that an electoral officer had the election held in his own tavern, where the voters could consume straight away. However, inns were often associated with a particular political party or denomination, and Polish voters complained about having to vote in “German” restaurants full of German campaigners.

The public elections, as envisaged by the law, were given concrete form in the 1890s by the Reichstag and the government. In this context, public means that the polling station could be entered by anyone entitled to vote. He didn't even have to be a local resident. The self-appointed election observers or those sent by political parties were able to put the electoral boards in some difficulties, if only for reasons of space; some election observers were primarily contentious. Even if some electoral boards arbitrarily kicked election observers out, they were not least afraid of using their authority to make the election invalid.

In the German Empire it was not yet prescribed that an election day had to be a Sunday or a public holiday ; this was only decreed by the Social Democrats in November 1918. They feared that employers might deny workers free time to vote, which constitutional experts considered legal, but lawmakers did not. In the reality of the empire, however, employers tended to try to force employees to vote; the weekday election supported the feeling that voting was part of the world of work.

Electoral roll

In the UK and US, the voter was responsible for registering and being put on the electoral roll . On the island, a voter had to prove his eligibility to vote himself, which may have made it necessary to go to court. Millions of residents may have been prevented from voting. The more bureaucratic Germany, on the other hand, was obliged to register and held the state responsible for keeping correct electoral lists. In Hamburg in 1887, because of the many workers who often moved, 170 clerks were busy compiling the lists. This lowered the cost for parties and candidates to get their supporters to vote.

In the eight days before the election, voters could check whether they actually appeared on the list. At that time, two thirds of those eligible to vote made use of this right in Hamburg . It was initially disputed whether one could also see the names of other eligible voters, which was finally confirmed by the government. Parties made copies of the lists and paid a visit to the electorate or approached them by post. Social Democrats urged their supporters to check their entry, because in Berlin, for example, the apartment owners provided the authorities with the data of their tenants. Liberal apartment owners in particular did not always bother to register poorer tenants on the upper floors.

Counting

The electoral board declared the voting at the polling station over. The electoral officer then took the ballot papers or envelopes from the ballot box and counted them. If their number differed from the voting notes (of the voters), this had to be reported in the election protocol. As a result, the electoral officer opened the ballot papers or envelopes one by one and read the contents of the vote aloud. The election protocol was sent to the Reichstag together with the invalid ballot papers, the rest of them were kept sealed until the Reichstag had finally recognized the validity of the election.

A ballot paper was invalid if it was not white or had an external identification; contained no or no legible name; or a protest or reservation was added. Since the electoral officer had to send the papers to the Reichstag that were, in his opinion, invalid, the election review was usually able to consistently deal with disputed decisions. In particular, an alleged or actually misspelled name was often used as an excuse by some electoral officers. Since there was no threat of penalties for doing this, some electoral officers tried repeatedly to at least delay the election of an unloved candidate.

Finally, an electoral commission determined the overall results of the constituency. It was chaired by an election commissioner who was appointed by the government and usually held the top position in the local administration. He appointed six to twelve assessors who were not allowed to hold any direct state office; they were often notables who might belong to competing parties. A clerk in turn was allowed to hold a state office.

Four days after the election, the electoral commission had a public meeting in which it looked through the election protocols from the electoral districts and counted the results. If a candidate had an absolute majority of the valid votes, the election commission proclaimed him the winner. Otherwise, the election commissioner determined that a runoff election should be held, after which the election commission met again. If she had concerns about an election in the districts, she could put them on record.

In the first Reichstag elections in particular, it happened that some electoral commissions independently corrected the individual results or ignored entire electoral districts. The constituency result was therefore canceled three times. In one of these cases in 1874 an election commission in Opole did not include the results of two electoral districts in the overall result, so that the German candidate won. Just as the local election commissioner was not punished in Bromberg in the 1881 election. The election commissioner had pretended that Adolf Koczorowski z Dembno and Adolph Koczorowski on Debenke were two different people. As a result, the votes for this Polish candidate were distributed, and the conservative candidate, who actually only came third, made it into the runoff against the first-placed left-wing liberal.

Direct election in a single constituency

In the elections in 1848 and then from 1867 onwards, electoral districts that each sent one representative were elected. In order to win the mandate, a candidate in the constituency had to gain an absolute majority of the votes; if none of the candidates succeeded, there was a second ballot a few days later, i.e. a runoff . In the runoff election, the two candidates who received the most or the second most votes in the first ballot ran.

So-called savages , candidates with no commitment to a particular parliamentary group, were still common in the beginning. But there was a strong tendency from people to vote for parties. Initially, there were only two candidates with a chance of success in many constituencies. “Riviera constituencies” were so sure to favor a particular party that the candidate could have stayed on the Riviera instead of campaigning. Later, however, conflicts within the liberal groups and the emergence of new competitors such as the anti-Semite parties resulted in contested constituencies. In 1871 there were 945 candidates, in 1912 by 1552.

The runoff favored the political center and thus the liberals, both left and right. In 1912, the Liberals received almost all of their seats in runoff elections, which somewhat offset their disadvantage as urban parties. The SPD, on the other hand, won only 27.4 percent of the 679 runoff elections during the German Empire. Often the bourgeoisie stood behind a common candidate in order to prevent a mandate for the Social Democrats, or “German” politicians united their forces against a “Polish” candidate. Runoff elections have politicized and integrated.

There are basic assumptions about the influence that an electoral system has on the party landscape. A relative majority electoral system ensures a manageable two-party system and a proportional representation system for a multi-party system , as Duverger's law claims. Such generalizations, however, do not always stand up to historical scrutiny. Not only details of the electoral system have to be taken into account, but also the voting society with its internal contradictions.

In Germany there was not only an opposition between conservatives and liberals, but liberalism also split into at least two parties after 1867. In addition, there was the (to put it simply) opposition between capital and labor, which favored a party like the SPD. There were also religious (Catholic Center Party ) and national (Poles, Danes, Alsace-Lorraine) minorities. Because of their often regional concentration, the majority electoral system enabled them to win in the constituency. Furthermore, because of the absolute majority rule, losers could unite and win in runoff elections. There were about as many parties in the Reichstag as there were in the Weimar Republic with its proportional representation system .

Constituencies

The constituencies were established for the first North German election in 1867, and in 1871 the South German constituencies were added. Since then, the division could only be changed by imperial law. The electoral area initially consisted of 382 constituencies. In 1873, 15 constituencies were added for Alsace-Lorraine , so that the total was 397 constituencies. This remained unchanged until 1918.

The government had proposed early on that the constituency borders should be renewed with every census , which the left-wing liberals had rejected. In 1856, the Prussian government arbitrarily moved the borders to meet the opposition (in the USA it is called gerrymandering ). The electoral law of 1869 then referred to the population figures in the elections for the constituent Reichstag of February 1867. However, as early as 1871, statisticians predicted that the observed differences between low-population and high-population constituencies would increase in the future. A (fundamental) reform did not take place until 1918, although the electoral law itself had suggested this: “An increase in the number of representatives as a result of the increasing population is determined by the law.” (§ 5), and: “Ein Federal law will determine the delimitation of the constituencies. Until then, the current constituencies are to be retained [...]. "(§ 6)

Nevertheless, there were some minor changes to constituency boundaries through imperial law, for example in the constituency of Opole in 1873. In addition, authorities sometimes changed the boundaries unauthorized, for example when in 1890 in the Prussian Rhine Province , municipal boundaries changed and with them constituency boundaries were adjusted. The electoral examination of the Reichstag in 1893 therefore declared two mandates invalid.

At that time, however, there was also a conscious intention to change boundaries in a way that was decisive for the election. A district president in the province of Poznan wanted to add a certain district of a constituency to the neighboring constituency. In that constituency, the Polish candidate received only a narrow majority, while the Polish majority was strong in the other. Due to the planned postponement, a “German” candidate would probably have won the next time in the first constituency. Robert Arsenschek: "What was astonishing about this action was above all the ignorance of a number of middle-class officials as far as applicable law was concerned."

Effects of constituency sizes

In 1912 there were 46,650 inhabitants in the smallest constituency, namely Schaumburg-Lippe . With around 12,000 eligible voters, the winner only needed a few thousand votes. The largest constituency, however, Teltow-Charlottenburg near Berlin, had 1.2 million people. At that time there were twelve constituencies with fewer than 95,000 inhabitants, twelve others had more than 400,000 inhabitants. In this oft-cited example, it should be noted that even small states like Schaumburg-Lippe should have their own constituency if possible. By the way, the respect for the borders of the federal states led to the fact that some areas that were far away belonged to the same constituency. The south-west German area of Birkenfeld, for example, was part of the north German Grand Duchy of Oldenburg and voted in its 1st constituency as did the inhabitants of Oldenburg-Stadt.

The division favored rural Germany and thus conservatives and the center, and it disadvantaged urban Germany with liberals and, above all, social democrats. In the election, a candidate took an average of ten thousand votes to be elected, while a Social Democrat took an average of 62,000 votes. In 1907 the average was 28,350 votes, 17,700 for a Conservative and 75,800 for a Social Democrat. Another election later, a conservative needed slightly fewer votes than the average and a social democrat about a third more. Voting blocks could certainly win more seats than the competition with fewer votes. In 1887 the conservative-national-liberal alliance received 3,573,000 votes (221 seats), and the opposition received 3,893,000 votes (176 seats).

However, such differences between large and small constituencies, with the corresponding consequences, have long been much greater in Great Britain. In 1886 the Liberals got 65,000 more votes than the Conservatives, who still got 104 more seats than the Liberals. In addition, the UK suffrage was fundamentally unequal: a voter had as many votes as he owned land (of a certain minimum) in different constituencies. In the German Reichstag election, however, each voter only had one vote. In contrast to the UK, however, inequalities in Germany were a particularly high-profile issue.

Constituencies

Since in Germany the constituencies were not or hardly changed, the Gerrymandering had more meaning on the level below, in the electoral districts. A certain group, such as Poles or Catholics, was assigned to a constituency where they had to vote under the eyes of another, larger group. Those affected complained while the communities wanted to continue to watch over the election act. The division also meant that certain voters could be expected to walk a long way or a short distance to the polling station.

There was only one upper limit for the population of an electoral district: 3500 inhabitants. An electoral district that was too large was rarely complained about. The problem, however, was small constituencies, where the low number of voters threatened voting secrecy. In a Mecklenburg constituency in the 1912 election, there were 78 constituencies with fewer than 25 voters each. Larger constituencies would have made it difficult for some voters to travel to some places. The obvious solution of counting the ballots of several districts together in a neutral place was not taken up.

Place of choice and place of residence

In other countries and in the German federal states, the right to vote was usually tied to a long period of residence in the electoral district. As a result, the mobile lower class was often not allowed to vote. The Reichstag election law only required that the voter be domiciled in the electoral district, without any further details. In this way it was possible to move loyal Social Democrats or Central People from a safe to an even more insecure constituency at short notice. Only a sleeping quarters had to be proven at the registration office. The SPD reacted extremely violently to attempts by the government and the conservatives to introduce a minimum residence of two years, for example, and the government backed down.

The phenomenon does not appear to have been as widespread as the rumors suggested, and the government and the right did not dare to amend the electoral law accordingly. This would have triggered demands for reform from the other side, primarily a reform of the constituency of the constituencies.

Candidates had to be citizens of one of the states eligible to vote (Section 4); In contrast to the USA, for example, they did not have to live in the constituency. It was not uncommon, especially with leftist candidates, to come from outside the country.

Discussion on proportional representation

The proportional representation , or as it was then that proportional representation has been proposed from time to time by representatives of all political views, but on vehementesten of the Social Democrats. A party organization was necessary for the establishment of (nationwide) lists, so that the changeover of the electoral system was interpreted as a shift from the “election of persons” to the “election of parties” - although even in the course of the empire completely unrelated MPs became rare and the voters separated oriented more to the party than to the person.

In his 1901 work on the right to vote, the constitutional lawyer Georg Meyer wrote that opinions were divided. The proponents overlook the fact that voters are not simply supporters of a political party. Despite their necessity in the constitutional state, the parties should only be a means, not an end in themselves. The state structure follows the local districts, such as provinces, counties and municipalities, just like the British House of Commons consists of representatives of the municipal associations.

Fritz Stier-Somlo pointed out in 1918 that the proportional representation system was not very popular because of its complexity (for example through the transfer of votes). It will be difficult to establish itself in medium-sized and large countries because it is not useful there. In connection with other electoral systems, the practical usability is still to be tried out, it still takes the minority into account and makes runoff elections unnecessary.

In 1903 proportional representation was introduced in the local elections in Bavaria, in 1906 in Württemberg and Oldenburg in 1908. In the state elections in Württemberg and Hamburg in 1906. At the national level and in all states in general, it was introduced in 1919 with the elections to the Weimar National Assembly and other constituent bodies in the states.

Secret election

The Reichstag elections were in themselves secret, more precisely it said in the Federal Electoral Act of 1869:

"§ 10. The right to vote is exercised in person by means of concealed ballot papers to be placed in a ballot box without a signature.

The ballot papers must be made of white paper and must not have any external identification. "

Voting secrecy as a goal was not a matter of course in the 19th century, so voters in the Bavarian state elections had to sign their ballot papers with their names. Some voters wanted to prove how they voted out of deference, others showed their ballot to the reinsurance electoral officer that the sheet was filled out “correctly”. While the election itself had to be public and traceable, the election act was private. This tension resulted in discussions in Germany, but also in Great Britain, about the nature of the election. While the older research assumed that the election was secret in the Empire, contemporaries (confirmed by local studies) assumed it wasn't.

In practice, there were significant problems for voters who actually wanted to prevent other people from knowing which candidate they wanted to vote for. They had to fear that their ballot paper would be recognized as a slip of paper from a party, or that after being thrown into a ballot box, the electoral board could see which ballot paper came from which voter. The liberal Robert von Mohl called the current election procedure a "mockery of the secret required by the law".

Ballot

The freedom of choice was jeopardized not least by the fact that each candidate had to ensure that a ballot paper was available with his or her name on it. As long as there were no government-printed ballot papers and no voting envelopes, voters had to fear for their voting secrecy.

Many parties did not appear to be interested in standardizing ballot papers, although this had been the practice in Canada since 1856 and in many countries since the 1880s. In 1869 prominent liberals had already made the proposal in the Reichstag. It was not until 1923, in the Weimar Republic, that the state took over printing the ballot papers. These then listed all parties involved, from which one ticked.

distribution

Originally, ballot papers were supposed to be printed and distributed by the state, which some states did in 1867. Prussia, on the other hand, feared logistical problems with the distribution, for example that lower-class voters could go home early while queuing in long lines. Each voter was responsible for showing up on election day with a ballot for his candidate. As a rule, the ballot papers came from the candidates or their parties, who in turn had considerable problems distributing them. The ballot papers cost about a hundred marks per constituency in 1907, and it took more than fifty polling workers to distribute the 25,000 ballots in a rural constituency in the 1880s.

In Prussia and Saxony in particular, the authorities themselves distributed ballot papers for politically acceptable forces and at the same time hindered the distribution of “opposing” ballots. Unclear rules in the federal states gave Prussia the opportunity to treat ballot papers as printed matter in the sense of press law, which require police approval. The biggest problem for the freedom of choice, however, was "a mixture of eagerness to serve and insecurity in dealing with an ambiguous legal situation", especially in the lower bureaucracy, which did not know whether and what they were allowed to confiscate (Arsenschek). After the Reichsgericht had ruled in 1882 that ballot papers were printed matter within the meaning of press law, the Reichstag in 1884 passed a law adopted by all parliamentary groups (Lex Wölfel) that ballot papers were not such printed matter.

Sometimes the chairman of the electoral board had the advantage of being able to hand one of his papers to voters without papers. Ballot papers were only allowed to be distributed outside the polling station, but the boundaries were fluid, for example when the electoral officer sent the voter to his wife in the kitchen to pick up a "suitable" one. The electoral examination of the Reichstag protested when the electoral committee itself distributed pieces of paper. At first it was just as inadmissible for a pile of ballot papers to be displayed in the polling station, later the Reichstag tolerated this as long as voting papers from all parties were offered.

Missing norms

The ballot papers were not standardized, so a party could make its ballot papers recognizable for everyone by selecting the color or format or certain edges. This was done by a party that was able to exercise power on those who thought differently in order to be able to recognize the voters of the other parties. In addition, the dominant party sometimes printed its notes on a type of paper that was difficult to obtain , or so late that the other parties could no longer imitate the appearance. Many a shrewd voter used the opponent's ballot paper, but crossed out the printed candidate's name and added another by hand. Such ballot papers, however, have often been declared invalid by the election boards.

Unlike in other countries, voters were not allowed to throw their folded ballot into the ballot box themselves, but had to hand it over to the electoral officer. The reason for this was that a voter should not be able to throw in additional pieces of paper hidden up their sleeves. In this way, however, many a high-handed election officer could simply open the ballot and see for themselves whether a good candidate should be elected. If he respected the right to vote more closely, he could, for example, add a small notch to the ballot with his thumbnail and later identify the voter. If the electoral officer was the same person who previously pressed the voting slip into the hand of a voter, he could mark the slip with a pin prick or in another harmless way. During or after the counting, he then recognized whether this slip of paper had also been handed in.

Envelope and voting booth

The center and left-wing liberals had long been calling for an envelope and, since 1889, a voting booth . In 1894 the Reichstag voted in favor, the Federal Council against. Ultimately, only the Conservatives remained of the opponents, as the National Liberals reacted to a change in opinion in the educated middle class. The latter had become more sensitive to government influence in the climate of the labor disputes and the government's threats of coup d'état at the time. In 1903 the envelope and voting booth were introduced, the latter to the derision of conservatives and tabloids.

However, the voting booths were often insufficiently suited to guarantee a secret ballot, for example when the privacy screen concealed the voter from the electoral board but not from the rest of those present. Some employers stayed longer in the cabins to check their workers. The Reichstag was not consistent in punishing such violations, which among other things depended on the majority of the Reichstag in question. The changing attitude of the Center Party suggests that voting secrecy was not entirely welcome, especially in rural areas.

Despite the voting booth, the order of the voters could still be determined if the envelopes were bulky and the urns were small. The surveillance had gotten worse, according to Anderson; When in 1903 social democratic election observers demanded that the ballot box be shaken, they were imprisoned for four months for presumptuousness. Arsenschek is more cautious with a judgment about the value of the reform, but notes that in any case the Prussian voters could not be sure of the election secrecy even after 1903.

All kinds of containers were used as urns, from cigar boxes to saucepans. It was not until 1913 that the Reichstag standardized the urns with a change to the electoral regulations. They had to be square, at least three inches high, and at least four inches wide between the opposite walls. The gap in the lid of the urn could not be more than two centimeters wide. These standardized ballot boxes were still used in some substitute elections for the Reichstag.

Election Challenges

After a parliamentary election, voters or unsuccessful candidates may question the legitimacy of the mandate. The subsequent review may continue the election campaign by other means. In Great Britain and Sweden, in the late 1860s, it was ruled that the Supreme Court should resolve disputes. In many other countries, however, following the French model, it was assumed that the election test was the very right of parliament itself. In Germany this was followed by Baden from 1818/1819, while in Bavaria, the two Hessians, Saxony and Württemberg there was a commission from the sovereign. The Frankfurt National Assembly partially accepted the French model and the rules of procedure of the North German Reichstag in 1868 definitively. At the beginning of a legislative period, the representatives were assigned to departments by lot.

The high number of election results (in the individual constituencies) that were contested was peculiar to the German Empire. In Great Britain, for example, a controversial election result was viewed as a private conflict between the candidates. If a defeated candidate wanted to challenge the election in his constituency, he had to travel to London with his witnesses, from 1868 the judges and lawyers traveled to the constituency - at the plaintiff's expense. That alone made the challenge, like the high bail, extremely expensive. Election disputes were rare and British parliamentary seats were reserved for very rich gentlemen.

In Germany, on the other hand, elections were considered a public task and their legality was a matter for the state. The cost of the review was borne by the state concerned. Within ten days of the election, every German (since 1892: only eligible voters from the constituency concerned) was allowed to contest the result, and a hearing in the Reichstag took place. The election review commissions were composed of members from various parties.

The alleged electoral secrecy was tried to throw off contestations because of suspected electoral influence . In addition, some complainants tried to use voter surveys in the constituency to prove that an election result could not be correct. As a rule, the Reichstag rejected this, as otherwise the voters would have had to be asked under oath what they voted, and this would have violated voting secrecy. However, contrary to the intentions of the state, the electoral system also led to politicization. The task of distributing ballot papers mobilized the parties, who offered outsiders a new community outside the village community. This did not necessarily make the elections free, but it did make them competitive.

If a constituency result was declared invalid, a replacement election took place. This happened rarely: 78 times during the German Empire. But the simplicity of the challenge led to a culture of complaints and to a great deal of attention for actual or alleged wrongdoers.

After the founding of the Reich, the Reichstag was still trying to enforce freedom of choice, Robert Arsenschek concludes his study on the election test. At the turn of the century, however, the center turned to government, and the parliamentary majority became more cautious and oriented towards government interests. “Since then, the Reichstag has not actively contributed to the democratization of the electoral reality or to a parliamentarization of the political system. The parties close to the government had made themselves comfortable in the forecourt of power. "

Actual election violations

In contrast to Great Britain, for example, there were few direct election violations in Germany, such as serious bribery with money; at most, the candidates distributed small rewards in kind such as sausage or beer. Even those who challenged an election did not see voters as for sale. In addition, elections meant the loss of life for very few Germans, for example in fights. In contrast, significantly more people died in Italy, Ireland, Spain or the USA, for example, and in some cases also because of the state. In Cincinnati , a poll was considered quiet if fewer than eight people died. In Louisiana , more than two hundred blacks were murdered in a single constituency in 1869. Furthermore, election fraud such as the submission of several ballot papers in bureaucratic Germany is seldom to be assumed, even if there have been a few proven and punished cases.

It was also rare that someone voted who had no right to vote, a foreigner for example. The fraud did not come so much from political parties but from inexperienced people from the lower classes who wanted to be politically active. Whenever they heard from someone who didn't vote, they tried to impersonate them. At the time, a lawyer assumed that even a few hundred such cases were unthinkable. There were even SPD functionaries who reported the attempted multiple voting by overzealous supporters. According to Anderson, such scruples caused astonishment in other countries: When the Social Democrat Eduard Bernstein was once in London, a Labor friend registered him as a voter. Bernstein insisted on not being British, when the friend said that if the political opponent found out, it would be his job to get Bernstein's name off the list.

Unlike bribery, physical violence and electoral fraud, “influencing the election” was not prohibited by the Criminal Code . Much could be understood by this, and some contemporary experts even suggested that it was a human right to influence other voters. A voter must also be mature enough to decide whether he wants to be influenced or not in his election (which was ultimately secret). Secret election and maturity in the empire are to be discussed, so Margaret Anderson, but the election results do not suggest that the voters were "in the stranglehold of the powerful". In 1871, the parties loyal to the government only received 56.5 percent of the seats, despite the mood after the victory over France. In the last election before World War I, in 1912 , it was only a quarter of the seats - “a remarkable number considering all that has been read about the effectiveness of authoritarian institutions in Germany.” In practice, freedom of choice was less under pressure of the state as the village community. In (smaller) towns and villages there were noticeably many unanimous election results. As with medieval applause, it was not necessarily a question of selecting the best candidate, but of symbolizing the collective will of the community.

Methods of influencing

The attempts to influence were of various kinds. Some electoral boards did not allow any election to be held; others ignored the requirement to disclose election lists for eight days before the election; manipulated the electoral lists by accepting the incapacitated or criminals; made use of their knowledge of those who had already voted and only let messengers bring those non-voters who voted in the interests of the electoral board; voided ballot papers quite arbitrarily; kept the full urn at home despite different regulations. Sometimes master craftsmen cast ballot papers for their journeymen or priests for parishioners, which some electoral boards allowed despite the prohibition of representative elections.

Official election policy

In the Kaiserreich the Reichsleitung (the Reich Chancellor with his State Secretaries) was not appointed by the Reichstag, but they needed a majority in the Reichstag for their bills. So she had a motive to influence the elections. Robert Arsenschek describes it as official election policy when the Reichsleitung wanted to bring their officials into line so that the officials on the one hand voted in the interests of the government and on the other hand exerted influence on the elections and voters. The Reich leadership succeeded in doing this more easily in Prussia than in the other federal states.

In Baden , for example , state officials were threatened with professional and other disadvantages if they stood up for candidates other than national liberal. Whether this actually had consequences depended on the individual case. In 1878, for example, a postman was disciplined for distributing conservative ballots. In Württemberg, the government informed the district governments confidentially about their political ideas and let them work towards the desired results.

In Prussia and similarly in Saxony the efforts were very far-reaching. The government became particularly active when it feared that the parties loyal to the government would be weakened in the elections. The Prussian government therefore held back in the first elections after 1871, among other things because it could count on the civil servants to exercise their power of their own accord in the interests of the government. Particularly at the lower and middle levels, considerable momentum was able to develop. However, the government actively intervened against officials who supported opposition parties in the election campaign. The voting itself was rarely objected to, in contrast to the state and local elections without election secrecy.

In 1878/1879 Chancellor Bismarck ended cooperation with the Liberals; as a result, the Prussian government developed a sophisticated system of strong electoral influence. The occasion was an incident in 1878 in the second constituency of the Duchy of Saxony-Meiningen . The district administrator had let his party comrade Eduard Lasker live with him and took him to a national- liberal election date in the service coach . Bismarck complained to the Meiningen government that Lasker leaned towards the left-wing liberals. As a result, the Meiningen government reprimanded Lasker and assured Bismarck that the district administrator would be dismissed if another incident occurred.

In later years, especially after the dismissal of the Prussian Interior Minister Robert von Puttkamer in 1888, the election policy for officials declined again. Conservative organizations had been founded that, to a certain extent, relieved the government of influencing the election, such as the Federation of Farmers or the German Fleet Association , which worked closely with the Reichsmarineamt. In 1898 the Prussian government again worked out confidential guidelines which the upper presidents were to pass on orally in their provinces. The main opponent has always been social democracy and the representatives of a national minority such as the Poles and Danes. The center and the left-wing liberals ( progressive , liberal ) were supported or opposed depending on the alliance policy of the Reich leadership. The officials should always avoid coming out too publicly.

There were also “official calls for elections”. Voting calls were often printed texts and leaflets distributed in support of a candidate or a party. A politically active district administrator, for example, was allowed to publish such an election call as a private person without an official title. If, on the other hand, he wanted to stand out in his capacity as district administrator, the announcement could only have general content. Otherwise, the election examination of the Reichstag would have criticized the use of official authority for one candidate against another. However, the Reichstag generally accepted it when an element of the executive lowered the opposition, for example as "Reich enemies".

The election policy of civil servants had its limits, and in the years leading up to the last Reichstag elections in 1912 there was a discussion about civil servants' freedom of choice. In 1911, a progressive MP caused a lot of media coverage when he said that an official exercised his right to vote not as an official but as a citizen. The discussion was also fueled by the civil servants' greater inclination to organize themselves professionally and to become more independent from government influences. In the same year, when drafting new principles, the Prussian government had to recognize that, because of the secrecy of the elections, the election decision of an official could not be determined without further ado.

Electoral influence by clergy

For the Catholic Center Party , especially because of its loose party organization in the German Empire, the support of the Catholic clergy was of the greatest importance. In contrast, the role of the Protestant clergy has not yet been clarified. In general, state influence was more important among Protestants. The Protestant clergy were closely linked to the state through the sovereign churches. In the province of Hanover , clergymen could get into trouble if they supported the anti-Prussian German-Hanover party .

In Bismarck's time, the selection of Catholic candidates was a matter for the local lower clergy, who generally had a great influence in the electoral associations. Later, the selection of candidates went to the party organizations in the provinces. The clergy avoided speaking directly at election events, but set church services on unusual dates at which liberal events took place at the same time. They distributed ballot papers, also in the church, and also used acolytes or school children for this purpose . On election day, clergymen were sometimes at the polling station, and some had announced beforehand that they knew what the ballot papers were like. It also happened that clergymen threatened with undesirable election results of the congregation with fewer church services, that they wanted to refuse apostate voters absolution, last rites, marriage, baptism of children, etc., or that they asked those concerned before confession what they voted for had.

The success of the Center Party as early as the early 1870s led to the assumption that spiritual electoral influence was the reason for this. Well-known Liberal and Conservative MPs had to vacate their seats, believed to be safe, to Catholics. In the climate of the Kulturkampf , the Reich leadership and liberals saw anti-modernism rise. The Reichstag's election examination accepted it if the clergy were organizationally involved in the election campaign. Even a list of signatures was tolerated, with which voters virtually committed themselves to the election of a certain candidate. However, the limit was exceeded when a clergyman directly used the authority of his church office.

The pulpit speeches in particular were a thorn in the side of the opponents. Even the central politician August Reichensperger said that the clergyman should at most present general religious truths, while his colleague Ludwig Windthorst found nothing against being called for a certain candidate to be elected. Otherwise one has to prove that what the priest demands is actually happening. After all, there is an electoral secret and one starts from the responsible citizen. If the liberals don't think so, Windhorst said, they'd better abolish universal suffrage. For their part, the Liberals worried that the voter might be controlled by other than purely political and secular considerations - because of spiritual influence. So three mandates from the center were cashed in 1871 because of influence from the pulpit, whereby the Liberals remained silent about two cases in which Catholic clergy supported the Liberals.

At the end of 1871, a majority of the Reichstag decided in favor of the so-called pulpit paragraph , influenced by the debates on the electoral examination . The prohibition of political agitation from the pulpit had also and precisely been decided because of the election campaigns, but it had little significance. In 1878 the Kulturkampf subsided, and the center approached the Reich leadership. Recommendations from the pulpit for a candidate were accepted, only threats from the clergyman were not.

According to Anderson, there has been a lot of criticism of the influence of the Catholic clergy, referring to both voting and confessional secrecy. If someone voluntarily accepts an external authority, it is no longer necessarily to be called external. The pressure on believers came about less from church punishments than from a certain culture, and this tension between the voter's own convictions and the mobilization of a community is difficult to grasp. With the Protestant majority, however, the image of an immature Catholic people that was manipulated by the priest was solidified.

Influence by the employer

In the traditional working world, the employer was responsible for the public life of his employees, which decreased in the second half of the 19th century. Nonetheless, economic power had a lasting major influence on the voting behavior of employees. In the country the proverbial conservative landlord was the employer, in the city the liberal or free-thinking manufacturer; in the east many landowners were conservative, but national liberal in the province of Hesse and national liberal or welfisch in Hanover . In West Prussia and Posen the Polish nobility also exercised their power over the farm workers. Elsewhere, the progressives were influential on the rural population, also through their position in local administration or horse breeding competitions. Universal suffrage, Anderson said, has not made the rural population less dependent, but it has changed the relationship between traditional rulers, landlords, and the government.

Compared to Great Britain, the German estates were much smaller, but the constituencies were larger. A squire might exercise his power in his constituency, but for a candidate to win, coordination with other constituencies, an agreement on a common conservative candidate, was necessary. The old conservatives in the East did not understand this, and when Bismarck withdrew their favor in the early 1870s and failed to provide coordination, the old conservatives suffered drastic losses in mandate. It was not until 1876 that they founded the German Conservative Party , but for a long time it was not very effective and could not even win favorable constituencies in by-elections. Conversely, Bismarck's turn for the liberals and radicals in 1878 meant that their (involuntary) helpers were no longer available.

The first Christian-social, then left-wing liberal politician Hellmuth von Gerlach remembered the conditions in rural Silesia in the 1880s:

“At that time the farm workers were politically the only factor in maintaining conservative rule. […] The village landlord did not dare to give up his dance hall at other than conservative gatherings, since the landowner, as head of office, could harass him in any way with uncomfortable behavior. On election day, the workers were led in a closed train to the polling station during the lunch break, the inspector in front and the forester in the back. At the entrance to the polling station, the inspector gave each worker the conservative ballot, which was immediately received by the landowner as the electoral officer. "

In the country, according to Anderson, the conditions were of the kind that Bismarck hoped for and the progressives feared. In contrast to the Catholic areas, there was hardly any election campaign in the Protestant lowlands. If necessary, aristocrats or farmers organized groups of thugs who attacked outsiders who appeared in the village. Baron von Richthofen-Brechelshof published advertisements in the local newspaper according to which he would fire all workers who voted incorrectly. In Wohlau -Guhrau-Steinau, a young evangelical pastor ran for the free conservatives, when the leader of the conservative district group had an advertisement printed, according to which this was a cheek, since the young man had previously been with him as a private tutor. Administrative power was added to economic power; in many manor districts, administration and jurisdiction were firmly in the hands of the nobility. A large landowner in Neunkirchen had all the houses on his estate searched for ballot papers for the Social Democrats and, as head of office, officially forbade the distribution of any further papers.

Mining entrepreneurs or manufacturers in the city also instructed their workers and threatened to lose their jobs; Usually this threat was carried out on the basis of individuals, as a deterrent, but there are also examples of mass layoffs. Employees were seldom dismissed, but were instead transferred to a sentence or otherwise disciplined. Politically reliable foremen or headmen were used to check workers on the way and only give them a slip of paper directly in front of the polling station. Anyone who did not accept it or who had their own slip of paper was noted.

In mining , forestry and the railroad , loyalty was particularly required. Foresters collectively led their subordinates to the ballot box, gave them voting papers and also looked into the ballot box; Center and Progress once wisely voted against the nationalization of the railways because they feared an increase in the number of voters for the government. In 1888 around a quarter of a million people worked for the Prussian state railway . Anderson: “Only doctors and lawyers whose clients weren't their superiors seem to have had no need to vote loyally. It is not for nothing that these professions are called 'liberal professions' in Germany. "

However, the power of employers had its limits; otherwise, for example, the losses of the liberal and conservative parties could hardly be explained. Germany at the end of the 19th century is associated with advanced urbanization and industrialization , but most of the workers were employed in smaller companies. They often changed jobs and were mostly not unskilled proletarians , but had a trade training. With the social democracy and its insurance systems - for example strike funds - a countervailing power arose. Such subcultures also existed on the part of the center, the left-wing liberals and the anti-Semites. Many employers simply could not afford to fire workers for political reasons. A single layoff had a deterrent effect on the other workers, but they showed solidarity with one another.

Another weapon was the boycott . If an employer fired someone for making the wrong choice, local social democrats could attempt a boycott of their products. It happened to innkeepers that guest groups stayed away for political reasons, for example when the innkeeper refused an election event out of consideration for other guest groups.

Debate and reforms 1917–1919

During the First World War (1914–1918) the parties held back in political disputes, in line with the truce policy . The Reichstag should have been re-elected in early 1917, but laws in 1916, 1917 and 1918 each extended the legislative period by one year. The right feared that the left would get stronger in new elections, while the social democrats feared open confrontation with the new opposition to their left (the Independent Social Democratic Party of Germany was founded in April 1917 ). There were probably by-elections for dead or resigned MPs, a total of thirty. The other parties almost always let the party of the previous mandate holder come into play; in one case the SPD took a seat from the anti-Semites and in another the Center Party from the Poles.

The discussions about a reform of the German electoral law, including the Prussian, received a great boost during the war. The reason for this was the fear of the ruling class of a republican revolution like the one that took place in Russia in March 1917 ( February Revolution ). Up until then, Russia had been considered a particularly backward country, and Germany did not want to lag behind. In budget discussions in March 1917, the SPD and the left-liberal Progressive People's Party spoke out in favor of electoral reform in Prussia, while the center still defended the rights of the individual states. Surprisingly, the National Liberals under Gustav Stresemann also supported such a reform, and also a certain parliamentarization of the Reich. The unity in the Reich should be maintained and the SPD should continue to approve the war loans.

Approach to electoral reform and parliamentarization

On March 30, 1917, the Reichstag established a constitutional committee. When Reich Chancellor Bethmann Hollweg wanted to make universal suffrage for Prussia more palatable to the emperor before the Easter message of April 7, 1917, he referred to the example of Bismarck and general conscription. One could not have a poor man with the Iron Cross vote next to a rich slacker under unequal suffrage. Unlike Bismarck in 1866, Bethmann did not dare to mess with the conservatives if necessary. The Easter Message of 1917 spoke of far-reaching reforms after the war, but it specifically did not provide for equal voting rights.

In the debates, the right to vote played the central role, more precisely, the extension of universal suffrage from the Reich level to the federal states. If the SPD wanted the same right to vote, the National Liberals instead thought of additional votes for older people. The reform in Prussia was seen as particularly important, since even if the Reich had been parliamentarized, the Reich leadership would soon have come into conflict with the largest individual state.

In May 1917, the constitutional committee had accepted a proposal from the left-wing liberals: In Reichstag constituencies with a large population increase, several mandates were to be awarded, which were assigned by proportional representation. A draft to the Federal Council of January 22, 1918 wanted to increase the number of members from 397 to 441. Of these, 361 constituencies remained, which continued to send only one representative each by majority vote. The remaining 26 constituencies, in large cities, should have a total of eighty members. The Federal Council accepted the draft on February 16 and the Reichstag on July 12. The middle-class bourgeois parties agreed, as did the majority Social Democrats . The reform threatened to put the SPD at a disadvantage, which in future had to share more of its city mandates with other parties. But working with the commoners was important to her. The Conservatives, the Poles and the Independent Social Democrats opposed the reform.

Last attempts at reform and the November revolution