Ballot

A ballot , even ballot (not to be confused with the ballot ) is

- originally a slip of paper on which voters can handwrite their choice .

- a pre-printed sheet of paper showing a list of candidates and / or parties eligible for election . The candidate or candidates or parties are then selected by ticks or other markings that clearly indicate the will of the voters. The ballot paper is then folded in order to protect the voting secrecy and thrown into a ballot box . At the end of the ballot, the number of (valid) ballot papers submitted is counted and the election winner is determined.

- the electronic form of a traditional voting slip; is used for both voting computers and internet voting.

Germany

Bundestag election

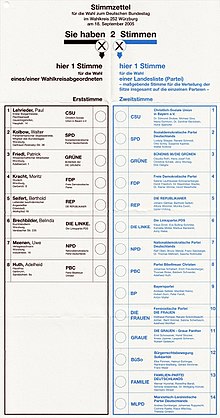

In the elections to the German Bundestag , there are 299 different ballots, namely for each constituency own version. They are "officially produced" according to Section 30 of the Federal Election Act (BWahlG or BWG) including the envelopes. Each voter has a first and a second vote . With the first vote , the direct candidate is elected in the respective constituency . The individual candidates are printed on the left of the voting slip. The order is based on the strength of the parties for which they stand in the last federal election (second votes). This is followed in alphabetical order by the direct candidates from parties without state lists and from groups of voters or individual applicants who have been admitted to the respective constituency. With the second vote, the state list of a party is elected, printed on the right of the voting slip. The order of the parties on the ballot papers is also regulated in Section 30 of the Federal Election Act. First, the parties already represented in the Bundestag are listed according to their results in the last Bundestag election in the respective federal state. This principle also applies to all parties that participated in the last election but did not move into the Bundestag because of the five percent hurdle . Then the state lists of the parties that are running for the first time are listed alphabetically. The CDU is currently number one in 13 federal states, the SPD in Bremen and Hamburg and the CSU in Bavaria. For use in voting templates for the visually impaired, the ballot papers are cut or punched at the top right corner. The stencils themselves are produced by associations for the blind in accordance with Section 45 of the Federal Electoral Code (BWO). Voting slips can be marked for representative election statistics .

According to Section 45 of the Federal Electoral Regulations, a ballot paper must be at least 21 × 29.7 cm (DIN A4) in size and made of "white or whitish" paper. In addition, the paper must be so thick that after marking and folding by the voter, other people cannot see how the person in question voted. According to the BWO, font, font size and contrast should be selected in such a way that legibility is made easier.

Elections to the works council, the staff council and similar elections

In addition to the political elections, in Germany the company representatives in the private sector ( works council ) and in the public sector ( staff council ) are elected by secret ballot (more on works council elections ). For ballot contains § 11 paragraph 2 of the Electoral Code to the Works Constitution Act a provision that can be generalized: "The ballots ... must all be the same size, color, texture and labeling." This indistinguishability of ballots issued is one of the most important prerequisites for to actually live up to the claim of a secret ballot.

Austria

In Austria , at the ballots between an official and an unofficial distinction ballot:

- Official ballot: This is pre-printed by the authority itself during the election. The candidates are listed below with the option of ranking or deleting them. The ballot papers must be counted both at the beginning of the election and at the end of the election. Official ballot papers are provided for each election.

- Unofficial ballot: Both blank sheets and forms from campaigning parties or candidates can be used. The counting is more difficult, as there can be several pieces of paper in one envelope, but they can only be counted as one vote. The use in the state elections or municipal council elections differs and depends on the federal states.

Ballot papers without a form

In some countries, ballot papers are used for personal elections that do not provide any options, but instead have to be filled by the voter with a name. In Switzerland, voting slips without a pre-printed form for major elections , for example for many cantonal governments , are filled out by voters with the name of the desired candidate.

In elections in Japan , ballot papers are usually printed with a rectangle in which the voter writes the name of the candidate to be elected or, in the case of proportional representation at the national level, the preferred party list. Only the confirmation of the judges of the Supreme Court always takes place via lists to tick.

Even in elections to the Congress of the Philippines , in Sweden and in local elections in Germany, for which no candidates are available, "blank ballot papers" are sometimes used without predefined options.

Some ballots with pre-printed list include a "none of the above" option (Engl. None of the above , just NOTA), which also allows the voter to specify a name not shown on the list. In the United States, for example , such write-in candidates are explicitly provided for in many sub-national area codes .

Design of the voting slip

The design of the voting slip can influence the outcome of the vote. It should therefore be neutral in democratic elections. A well-known example of a manipulative design is the ballot paper for the referendum on the connection of Austria : The yes field was significantly larger than the no field. The order of the parties on the voting slip is also important. Parties that are at the front of the ballot paper (especially in first place) thus receive additional votes (this is a case of a sequence effect ). In many cases, election posters are also advertised using the front list position. Since, in the interests of neutrality, all parties should be treated equally, but naturally there can only be a first place, various procedures are common:

- Order according to the strength of the party in the last election

- Random order

- Alphabetical order

The effect of ballot position effects and ballot layout effects is theoretically based on two models:

- Since reading from top to bottom and left to right, the top / left names are read first. These entries read first would be better cognitively anchored than subsequent entries

- The model of a "satisfaction principle" assumes that the voter reads the ballot only until he finds a sufficiently satisfied candidate and then stops the search.

The addition of notes to the ballot paper can also be manipulative. For example, in the municipal elections in Rhineland-Palatinate in 2014 , the Constitutional Court of Rhineland-Palatinate prohibited specifying the gender proportions of the representative body to be elected, which, according to the will of the red-green state government, should have increased the proportion of women in the elections. The information on the voting slip is regulated in the respective electoral law. Some scope for design is provided here. The Hessian municipal electoral law regulates that the district council or municipality can decide for themselves whether the municipality or the district of the candidate appears on the ballot.

(later replaced by a neutral version) Ballot for the runoff election in Bad Homburg before the 2015 level: The ballot in the column of the incumbent accidentally contains the note "Please tick in this column"

history

In ancient Greece , potsherds were used with a name carved into them. This is where the name shard dish came from . The voters brought the already labeled fragments to the agora without having to pay attention to secrecy. In the Roman Republic , voting was done using small wax tablets. After that, the importance of elections decreased more and more. In the Middle Ages, offices were filled through elections, so different colored balls were used ( ballotage ).

The members of the English Parliament were initially elected by acclamation and later by oral voting for the record. The primary elections (of the electors) for the Third Estate of the French French General Estates were designed in a similar way , with the actual elections for deputies being carried out using specially labeled ballot papers. This form of voting then shaped post-revolutionary France.

The diversity found abroad was also reflected in the states of the German Confederation . In the Frankfurt National Assembly, the members of parliament fiercely argued about the introduction of secret voting, which was still unusual until then, and the majority ultimately voted in favor. Even if the Frankfurt electoral law was not applied, numerous states of the German Confederation followed its principles. In Prussia , on the other hand, public voting remained on record. The elections for the North German Reichstag (1867) and for the German Reichstag (1871) took place in secret - according to the principles of majority voting. Initially, forms were used on which the name of the preferred candidate had to be entered, later the candidates themselves provided slips of paper with their names and had them distributed among the voters. They were not allowed to be displayed in the polling station.

With the November Revolution of 1918 proportional representation was introduced. Now it was no longer the individual candidates but the parties who provided the ballot papers with their applicants and distributed them as usual. Initially, the Reich government did not see any reasons for changing anything. It was only in the course of the inflation of 1923, when paper consumption soared and saving became the motto, that she thought of allowing countries to use ballot papers with all party lists. This practice, developed in Australia, was known from the USA, Great Britain and Belgium. The legal committee of the Reichstag, above all the BVP deputy Konrad Beyerle , did not want to be satisfied with that. All Germans should vote according to a model. Beyerle, a legal historian at the University of Munich and a well-known advocate of the legal claims of the House of Wittelsbach, justified this in the Reichstag on December 8, 1923: The compulsory collective ballot, which was previously naturalized “preferably in America”, “put an end to the waste of paper that was previously with everyone The election campaign was driven by the pressure of billions of unnecessary ballot papers ”. He put an end to the expenses of the parties for distributing and sending the ballot papers, with the cost of millions of envelopes, address letters and stamps. In future, voters received the official ballot papers at the polling station. There it is up to them "to indicate in the secret voting booth before submitting the ballot paper by means of a small cross placed on the ballot paper or in some other way which of the multiple district election proposals that are combined on the single paper he wants to vote for" . The good experiences that had been made in state and local elections in the state of Anhalt, however, had "eliminated the many concerns about the judgment or the eyesight of a voting old man or woman". This was not only doubted by the German national MP Schultz, who also assumed that the parties had a lively interest in continuing to “delight” their voters with election advertising, which would mean “all the savings for the cat”. The communists also suspected that voters - with the exception of their own, of course - could be overwhelmed with the American ballot in the "darkroom". The new official ballot papers were used for the first time in the Reichstag elections on May 4, 1924. They differed significantly from the ones used today. The circles crowded together to tick. The electoral boards had to check not only from top to bottom, but also horizontally, which proposal was flagged. It was too complicated. In the following election to the Reichstag on December 7, 1924, the list-like arrangement of the parties, which is still common today, was adopted.

With the takeover of power by the National Socialists, the diversity of parties ended and with it the possibility of choosing between different parties. In the Reichstag election of November 12, 1933 , the only option left to the voters was to tick the list of the NSDAP or leave it. The Reichstag elections of March 29, 1936 were also shaped .

With the collapse of the National Socialist dictatorship and the German surrender, the voting system introduced in 1924 was revived in the western occupation zones. In the election to the 1st German Bundestag , voters only had one vote, which was counted twice (for the constituency candidate and the party list). The two-vote suffrage , which is still in use today , was first used in the federal election on September 6, 1953 . It represented a compromise. The federal government wanted to continue the previous voting system with double counting for the constituency and the federal list, albeit in the manner of the so-called trench voting system . The SPD parliamentary group opposed this and wanted to adhere to the principles of proportional representation. At the suggestion of the FDP parliamentary group, the legal committee of the Bundestag then agreed on a two-vote right to vote based on the overall distribution of mandates based on the second vote result. First and second votes should be cast on separate ballot papers. This seemed superfluous to the SPD. At their request, the Bundestag decided to print the list of constituency candidates and the party lists on a ballot paper.

There is no such connection between two lists in the European elections. Here the voters only have one vote. The reason is the legislature's concern that, due to the small number of directly elected MPs, a relationship of trust and responsibility between voters and MPs, unlike in federal elections, could not be established.

In the Soviet occupation zone, the rulers - after there had initially been semi-free elections - completely abandoned the principle of one election with the unity election of October 15, 1950. There was no longer even the possibility of ticking the election proposal of the National Front or of voting “yes” or “no”. In these sham elections the citizens of the GDR practically only had to fold the unchanged slip of paper into the urn (so-called slip folds).

Web links

literature

- Buchstein, Hubertus, Public and Secret Voting, Baden-Baden 2000.

- Klein, Winfried, From voting on and with ballot papers in Germany and elsewhere, signa ivris 12 (2013), pages 83–112.

Individual evidence

- ↑ [1] ( Page no longer available , search in web archives ) Info: The link was automatically marked as defective. Please check the link according to the instructions and then remove this notice.

- ^ Benny Geys: Candidates in Pole Position; in: WZB-Mitteilungen, Heft 113, September 2006, p. 33 ff., online ( memento of the original from September 21, 2017 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice.

- ↑ Rhineland-Palatinate: Court prohibits ballot papers with a women's quota, in: SPON

- ↑ § 16 Hessian Local Election Act, GVBl. 2005 I p. 197, online

- ^ Brenne, Stefan, Ostraka and the Process of Ostrakophoria, in: Coulson / Palagia / Brenne (eds.), The Archeology of Athens and Attica under the Democracy, Oxford 1994, pp. 13-24, 15.

- ↑ Mommsen, Theodor, Abriss des Roman Staatsrechts, 2nd ed., Darmstadt 1907, page 240.

- ↑ Buchstein, Hubertus, Public and Secret Voting, Baden-Baden 2000, pp. 168ff, 347.

- ^ Meyer, Georg, The parliamentary election law, Berlin 1901, page 529, 545f.

- ^ Meyer, Georg, Das parliamentarian Wahlrecht, Berlin 1901, p. 529.

- ↑ Klein, Winfried, From voting on and with ballot papers in Germany and elsewhere, signa ivris 12 (2013), pp. 83–112, 88f.

- ↑ Klein, Winfried, From voting on and with voting slips in Germany and elsewhere, signa ivris 12 (2013), pp. 83–112, 90.

- ↑ Section 11 of the Reich Election Act of May 31, 1869 (Federal Law Gazette, page 145); Section 13 of the election regulations of May 28, 1870 (Federal Law Gazette page 275) in the version of the amendment of April 28, 1903 (RGBl. Page 202).

- ↑ Klein, Winfried, From voting on and with voting slips in Germany and elsewhere, signa ivris 12 (2013), pp. 83–112, 91.

- ↑ Klein, Winfried, From voting on and with ballot papers in Germany and elsewhere, signa ivris 12 (2013), pp. 83–112, 92.

- ↑ Negotiations of the German Reichstag 1920–1924, page 12367f.

- ↑ Negotiations of the German Reichstag 1920–1924, page 12369f.

- ↑ Negotiations of the German Reichstag 1920–1924, page 12373.

- ↑ Klein, Winfried, From voting on and with voting slips in Germany and elsewhere, signa ivris 12 (2013), pp. 83–112, 93.

- ↑ Klein, Winfried, From voting on and with voting slips in Germany and elsewhere, signa ivris 12 (2013), pp. 83–112, 97.

- ↑ BAK B 136, 1714 fol. 57R.

- ↑ BAK B 136, 1711 fol. 127.

- ↑ BT print. 8/361, page 12.

- ↑ Klein, Winfried, From voting on and with ballot papers in Germany and elsewhere, signa ivris 12 (2013), pp. 83–112, 95, 96.