Luxembourg Fortress

The fortress of Luxembourg , in the Grand Duchy also proud with the simplified quote Carnot as Gibraltar vum Norde (translated High German: Gibralter of the North ) called, was until its demolition in 1867 a fortification of the city of Luxembourg is of strategic importance for the border region between France, the German Confederation and the Netherlands or Belgium.

Roman fort

In Roman times, two roads crossed on a plateau above Alzette and Petruss , one that led from Arlon to Trier and one that led to Thionville . A circular wooden palisade was built around this intersection , behind which the farmers of the area could retreat in the event of an attack. Not far from there, on the Bockfelsen , there was the small Roman fort Lucilinburhuc - from this name the later name Luxemburg developed via Lützelburg .

Castle

After the retreat of the Romans, the abandoned fort fell into disrepair until, in 963, the Ardennes count Siegfried I , as Count in Moselgau , exchanged the rights to the fort for land in Feulen near Ettelbrück (Sauer) with the St. Maximin monastery in Trier . He had a small castle built above the fort, which was connected to the plateau by a drawbridge . Over time, a settlement developed on the plateau, which after about 200 years grew into a small town. In the middle of the 12th century, a solid city wall at the height of today's Rue du fossé protected the city. In the 14th century a second city wall was built, which included the area of the Rham Plateau . A third later enclosed the city area up to the level of today's Boulevard Royal.

fortress

On November 22nd, 1443, Philip the Good had the city of Luxembourg captured and plundered by a surprise attack at night, the crew of the castle on the Bockfelsen was starved and surrendered on December 11th, 1443.

With the conquest of Luxembourg began a period of foreign rule by the House of Burgundy , the French, the Spanish and the Austrian Habsburgs . During this time the fortress was continuously expanded and adapted to the military requirements of the time. The casemates built by the Spaniards and Austrians are remarkable .

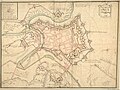

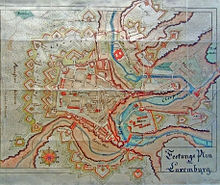

At the end of the development, the fortress of Luxembourg consisted of three ramparts , covering an area of 180 ha (area of the city: approx. 120 ha). Inside the fortress there were a number of bastions , 15 forts in the center and 9 more outside of it. A network of 23 km of underground galleries ( casemates ) was connected with over 40,000 m² of bombproof rooms .

In 1795 Luxembourg was besieged by the French revolutionary troops . The Austrian occupation of the fortress surrendered with the threat of defeat before their eyes and in fear of the looting and massacres. The French politician and engineer Carnot presented the victory as a great success for France, which made it possible to drive the war beyond the borders without danger. In his address to the French National Assembly , he described the fortress as "the largest fortress in Europe after Gibraltar" and, because of its function as a base, the greatest danger to France's opponents. The comparison referred to the previously unconquered Rock of Gibraltar on the southern tip of the Iberian Peninsula .

The fortress of Luxembourg as a fortress of the German Confederation

From 1815 to 1866, the fortress of Luxembourg was one of four fortresses of the German Confederation . The fortresses had the primary aim of preventing a French invasion of the territories of the German Confederation (to which Luxembourg was then a part). On the fringes of the Paris Peace Conference, the four victorious powers Austria, Great Britain, Prussia and Russia had designated the cities of Mainz , Luxembourg and Landau as fortresses of the German Confederation on November 3, 1815 and also planned the construction of a fourth federal fortress on the Upper Rhine .

The occupation of the federal fortress of Luxembourg with units of the federal army was originally supposed to consist of three quarters of Prussians and one quarter of Dutch people. In the supplementary tract of November 8, 1816, the Dutch king, who was also Grand Duke of Luxembourg, relinquished the right to Prussia to appoint both the governor and the commander of the Luxembourg fortress. In addition to the prescribed 4,000 men of the peace garrison, whose strength was not adhered to, a further 1,500 Prussians and 500 Dutchmen had to be brought into the fortress in the event of danger.

The strength of the war garrison of Luxembourg was thus fixed at a total of 6,000 men and 200 horses. This number was urgently needed because the fortress belt consisted of 22 forts, 15 of them in the middle belt and 7 in the outer belt. Large casemates and tunnels totaling 22 km in length had also been worked into the rock. For this reason, Luxembourg was also called the “Gibraltar of the North”. In 1867, the entire complex of this fortress with the surrounding fortifications had 24 forts.

The end of the fortress

After the Prussian victory in the German War of 1866, the German Confederation dissolved. Under the leadership of Prussia, the North German Confederation was founded as a federal state, but it no longer included Luxembourg; the Prussian troops remained in the fortress of Luxembourg for the time being. Before the war, the Prussian Prime Minister Otto von Bismarck had the French government under Napoléon III. signals that she can annex Luxembourg if she gives Prussia a free hand against Austria . After the war, however, he knew how to prevent this. 1867 Luxembourg was in the London Protocol of neutral states and determined that Prussia disbanded his garrison and the fortress should be demolished.

Luxembourg achieved complete independence after the death of King William III of the Netherlands . in 1890. Since his daughter Wilhelmina succeeded him to the throne in the Netherlands , but male inheritance law applied in Luxembourg, the personal union was dissolved. The Luxembourgers elected the German Duke Adolf from the house of Nassau-Weilburg as Grand Duke.

It would take a full 16 years, from 1867 to 1883, before the grinding of the fortress was finally completed. The grinding was more or less chaotic, in many cases parts of the fortress were simply blown up, the useful materials were taken away by the residents and the remainder was filled with earth. Nevertheless, it was decided to keep some buildings as landmarks of the city for posterity. These include the Vauban Towers in Pfaffenthal , three towers from the second city wall, the entrance to Fort Thüngen , the Jakobsturm with the towers at the barracks on the Rham Plateau, the Heiliggeist Citadel , the Castle Bridge and some of the Spanish turrets .

What may be considered the destruction of a historic building today was then the removal of an obstacle to growth for the city. The construction of new houses in the immediate vicinity of the fortress was generally prohibited for strategic military reasons (free field of fire, minimization of cover for potential enemies). These building restrictions hampered land development in Luxembourg City. When the corset of fortifications fell away, the city was able to expand into the surrounding area for the first time since the 14th century. In the south, the new Adolphe Bridge opened up the Bourbon plateau, in the west the Boulevard Royal was built with an adjoining large park.

Picture gallery

literature

- Michel Pauly , Martin Uhrmacher : Castle, City, Fortress, Big City: The Development of the City of Luxembourg. / Isabelle Yegles-Becker, Michel Pauly: Le démantelement de la forteresse. In: The Luxembourg Atlas [sic] - Atlas du Luxembourg. Ed .: Patrick Bousch, Tobias Chilla, Philippe Gerber, Olivier Klein, Christian Schulz, Christophe Sohn and Dorothea Wiktorin. Photos: Andrés Lejona. Cartography: Udo Beha, Marie-Line Glaesener, Olivier Klein. Emons Verlag, Cologne 2009, ISBN 978-3-89705-692-3 .

- Guy Thewes: Military order versus guild order The emergence of parallel economies in garrison towns using the example of Luxembourg fortress in the 18th century . In: Robert Bohn , Michael Epkenhans (ed.): Garrison towns in the 19th and 20th centuries. A publication of the Institute for Schleswig-Holstein Contemporary and Regional History and the Center for Military History and Social Sciences of the Bundeswehr (= IZRG series of publications . Vol. 16). Publishing house for regional history, Gütersloh 2015, ISBN 978-3-7395-1016-3 , p. 13 ff.

Web links

Individual evidence

- ↑ Friedrich Wilhelm Engelhardt: History of the City and Fortress of Luxembourg: since its first emergence up to our day: with special regard to the events of the war history; along with a city map and statistical introduction . Rehm, 1830 ( limited preview in Google book search).

- ↑ Raphael Zwank: Parts of the "Fort Olizy" exposed . ( Memento of the original from March 24, 2010 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. In: Luxemburger Wort , March 21, 2010.

- ↑ Merlin, P. Antoine (1795). Collections des discours prononcé à la Convention nationale .

- ↑ Klaus T. Weber: Federal Fortifications - An Introduction. In: The fortresses of the German Confederation 1815–1866. (Fortress Research Volume 5) Schnell + Steiner, Regensburg 2013, ISBN 978-3-7954-2753-5 , pp. 9–46.

- ^ Heinrich Eckert, Dietrich Monten: Das deutsche Bundesheer. Harenberg, Dortmund 1990, ISBN 3-611-00132-5 .

- ↑ Guy Thewes: Military order versus guild order The emergence of parallel economies in garrison towns using the example of Luxembourg fortress in the 18th century. In: Robert Bohn, Michael Epkenhans (ed.): Garrison towns in the 19th and 20th centuries. A publication of the Institute for Schleswig-Holstein Contemporary and Regional History and the Center for Military History and Social Sciences of the Bundeswehr (= IZRG series of publications. Vol. 16). Publishing house for regional history, Gütersloh 2015, ISBN 978-3-7395-1016-3 , p. 21 ff.

Coordinates: 49 ° 36 ′ 42.8 " N , 6 ° 8 ′ 11.8" E