Bourbon whiskey

Bourbon whiskey , or bourbon for short , is a variant of the American whiskey originally distilled only in Kentucky . It is produced as a distillate of a grain mixture with at least 51% corn , in addition to which it usually contains rye or barley . Further requirements are the alcohol content , which must not exceed 80% during production and not more than 62.5% at the beginning of maturation, and storage in new charred oak barrels. Bourbon whiskey can come from anywhere in the United States, but all but one of the major bourbon distilleries are in Kentucky or Tennessee .

A Tennessee whiskey is a bourbon whiskey that has been subject to further legal requirements since 2013. It is subject to the same requirements as bourbon whiskey. In addition, the whiskey must have been produced in the US state of Tennessee and have passed through the so-called Lincoln County Process - a filtration through charcoal . This means that every Tennessee whiskey is also a bourbon, but not every bourbon is also a Tennessee whiskey. The best-selling whiskey in the United States, Jack Daniel’s , is a Tennessee whiskey.

designation

Variants and information on the label

The designation as bourbon is determined by US law. The Code of Federal Regulations, Title 27, Section 5.22, 1964 specifies the framework conditions that make a whiskey a bourbon, as well as regulating certain information on the label such as straight , bonded, etc. Various international trade agreements protect the name almost worldwide, which means that bourbon whiskey may not be produced and sold as such outside of the USA . The production of American whiskeys, and thus also of bourbon, is monitored by the Food and Drug Administration and various manufacturers' associations such as the American Distillers Association and the Kentucky Distillers Association . The regulations on the names and classifications are subject to the American Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms and Explosives .

- Bourbon - must be distilled in the USA, the underlying mash must contain at least 51% corn. The alcohol content must not be more than 80% by volume during the fire and not more than 62.5% at the beginning of storage. As long as the bourbon is not marked as straight , in the USA it may contain up to 2.5% of its volume from additives under certain circumstances.

- Straight Bourbon - Must be aged in new American oak barrels for at least two years. The storage period must be stated on the label up to a storage period of four years. Straight Bourbon must not contain any additives.

- Kentucky Straight Bourbon - must be distilled in the US state of Kentucky and matured there for at least one year.

- Bonded Bourbon - a whiskey from a single distillery from a single vintage that is stored in special warehouses for at least four years. These are monitored by the US government and are called bonded warehouses in America.

- Tennessee Whiskey - must meet all the requirements of a bourbon. In addition, it must have been made in the US state of Tennessee and have gone through the Lincoln County Process . This technique was developed in Lincoln County, Tennessee, around 1820. The technology probably goes back to Alfred Eaton from the Cave Springs Distillery (now Jack Daniels). Filtration with charcoal itself has been used before to clean drinking water of impurities.

- Single barrel - whiskey from a single barrel. The term is not defined by law.

- Small Batch - Ger. Small amount of whiskey from a selected small amount, particularly well suited for maturing barrels in a warehouse in larger companies or the entire production in smaller distilleries. The term is not defined by law.

- White Dog / Legal Moonshine / Mash Whiskey / New Make distilled clear whiskey that has only been matured for a few weeks or months. Particularly popular with microdistilleries; may not be sold as whiskey in Europe.

Origin of the name Bourbon

It is traditionally assumed that bourbon was named after historic Bourbon County , an originally small district that now comprises 34 counties in the northeastern US state of Kentucky, where the first bourbon whiskey is said to have been made (however, later no bourbon produced at all). Bourbon County was again named after the French royal family Bourbon , in recognition of their support in the American War of Independence against the British.

However, the historian Michael Veach of the Filson Historical Society in Louisville , Kentucky assumes that the original story was only invented after the fact. While there had been labels with "Bourbon Whiskey" since the 1850s, this history of origins did not emerge until the 1870s. Veach suspects that the whiskey is named after Bourbon Street in New Orleans . There the whiskey from Kentucky became known to a larger group of buyers who tried to get "whiskey like in Bourbon Street" in other places.

Manufacturing

The legal requirement for bourbon production is that the mash must contain at least 51% corn . In practice, this is usually significantly higher. There is also barley and either rye or wheat. The whiskey is usually distilled with an alcohol content of around 70%, at the beginning of storage it is around 60%. There is no minimum storage time. A storage period of at least two years is required to be sold as straight bourbon. The duration of storage on the bottle must also be stated up to a storage time of four years. It is often matured significantly more than the prescribed two years, maturing times of 10 years or more are widespread.

fermentation

The corn is ground to a certain grain size, then mixed with fresh water from local limestone and boiled. After the mixture has cooled to around 65 degrees Celsius, ground rye or wheat and ground barley are added to add important enzymes for hydrolyzing the starch into usable sugars. Distilleries in the USA are the only ones who are already mixing the grains at this point in the process. Scottish and other whiskey makers distill each grain individually and first mix the distillate. Most large distilleries partially replace malt with an amylase- enzyme mixture. At this point, sour mash from leftovers from previous distillations is also added, which significantly reduces the pH value of the mixture and thus offers yeast and lactic acid bacteria good living conditions. After the mixture has cooled down to 21 degrees Celsius, either fresh baker's yeast or yeast from an earlier distillation is added to start fermentation and convert the sugar into alcohol. The fermentation lasts a few days before the fermented product called Beer , is brought to the distillery where the whiskey to about 70% alcohol by volume burnt is.

distillation

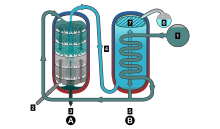

In the industrial production of the burning process is carried out now in the patent combustion process in Coffey Stills , that is, the fermented beer is from above into the internal bladder initiated and strikes of bottom-fed steam which the alcohol from the Beer dissolves and entrains. The mixture, the so-called low wine , is fed into the doubler , which basically works like a pot still and distills the low wine for the white dog with around 65% to 72% alcohol by volume. New mash is constantly fed in and the burner runs continuously. However, some smaller premium manufacturers continue to use the pot still process, in which the still is cleaned and refilled after each distillation process. Premium whiskeys go through three distillation processes, most of the others only go through two. The distillate, the so-called New Make , is then diluted with water to around 60% alcohol before it is stored in new oak barrels until it is mature.

The dominance of Kentucky and Tennessee in bourbon production is largely due to historical reasons. Before Prohibition, bourbon production was more common. Kentucky has established strong temperature differences that ensure a stronger aroma in the ripening phase. In addition, Kentucky and some counties in Tennessee have many springs with water directly from limestone. The water has a high pH, which helps fermentation. At the same time, it is rich in minerals such as calcium and poor in iron , which would give the alcohol an unpleasant taste. The Inner Bluegrass Region, in which the center of Bourbon production is located, is characterized by limestone from the Ordovician , the Outer Bluegrass Region, which adjoins it in a ring , is characterized by limestone from the Silurian .

storage

Bourbon whiskey is stored for at least two years in new barrels of American White Oak, the charred from the inside (Charred) is. The barrels are mostly made in the states of Arkansas or Missouri , with the wood itself coming from all over the east and central United States. Compared to French oak barrels, which are also often used to produce alcohol, whiskey matures more slowly in white oak barrels. The oak itself contains less tannin . The whiskey is usually stored in 200 liter barrels (53 gallons) in warehouses known as rackhouses , rickhouses or barrel houses . The storage time is at least two years. The industry standard is a storage period of four years, whereby for premium brands, six, eight or ten years are common and storage periods of up to 23 years occur. Compared to the evenly cool Scotland, whiskey in Kentucky matures faster with greater temperature differences and a generally warmer climate, but the proportion of whiskey that evaporates during storage is also higher. New wood also gives off more aromatic substances than the wood of used barrels, so that the whiskey matures faster, but if stored for a long time there is also the risk of overripening and the whiskey takes on a distinctly woody taste. Microdistilleries often use smaller barrels. On the one hand, to have a distinguishing and marketing feature compared to the industrial manufacturers, on the other hand, because there the surface is larger in relation to the content, and a shorter storage time is required to flavor the whiskey.

The barrels are preferably made from 80-year-old trees, because the verticalization is particularly pronounced in these , which in turn ensures that the barrels are particularly liquid-tight. The wood is usually stored outdoors for a few weeks after felling, so that the water content in the wood falls from around 40% to around 30%. This is followed by storage for a few weeks in a closed warehouse, where it is exposed to humidity at 30 degrees Celsius , which drops from 60% to 40% over the storage period. The wood then has a water content of around 20%. The last stage of preparation takes place in a kiln, where it is stored in dry air at 60 degrees for about a week. If the water content in the wood is 10 to 14%, it can be used to make storage barrels. After the barrels are made, they are charred from the inside. This is done by rotating flames that evenly distribute the char. There are five degrees of charring in total, each differing in the length of time the wood is exposed to the flame. The most common are grade 4 barrels in which the wood has been in contact with the flame for about a minute.

In the hot summer months, the whiskey expands and penetrates the wood. In the cool winter, it contracts again and extracts ingredients from the wood. At the end of the charring process there is a thick black layer inside the barrel over a thin layer of red wood before the wooden wall of the barrel begins, which has not changed due to the charring. During maturation, the black layer functions as a filter that absorbs certain substances from the whiskey. The red layer of wood in turn releases substances into the whiskey, especially vanillin , phenols (vanilla and spice aroma), quercus lactones (so-called whiskey lactones, with coconut aroma), and furan , a caramel taste. Maillard products add to the golden color of the whiskey. The requirement to use fresh American oak barrels originated on the one hand from the idea of supporting the local timber industry. On the other hand, however, fresh barrels release a particularly large amount of aromatic substances from the wood, so that the whiskey also matures faster. Due to the fresh wood of the barrels and the climatic conditions of its production region, Bourbon Whiskey reaches maturity after a few years. The oak barrels in which bourbon whiskey was made are often reused by other liquor manufacturers. The majority of all whiskeys around the world are aged in American white oak barrels, which were previously used to produce bourbon. These barrels often go to Scotland, where they are used to make single malt whiskey , or to Puerto Rico , where they are used to store rum .

history

prehistory

When bourbon whiskey was created, historic Bourbon County was still in western Virginia . The state of Kentucky was later re-established from part of Virginia. Immigration to the area along the Wilderness Road through the Cumberland Gap via the Appalachians began after France ceded the area to the United Kingdom in the Peace of Paris in 1763 . The west of Virginia was settled by Scottish and Ulster-Scottish immigrants, among others, in the early 19th century . After the Pennsylvania Whiskey Rebellion of 1794 , numerous Pennsylvania distillers moved further south and west and settled across the Cumberland Gap in what is now Kentucky.

In the early years of settlement in North America, gin and rum were the predominant spirits that were distilled on the east coast. This only changed with the push to the west. The raw materials for gin and rum had to be imported; the route across the Appalachians was so laborious that the distillers switched to basic products that grew locally. In addition to the made of apples Applejack the settlers also began to distill grain alcohol. The immigrants brought the technique of distillation with them from Europe. The first focus of American whiskey production was in the states of Pennsylvania , Maryland and Virginia . Rye whiskey, made from rye, was predominant here . The first corn beer brewed by the settlers in North America can be traced back to Connecticut in 1662 , although corn remained an exception as a raw material for alcoholic beverages in the east and north of the United States. Further south and west, the settlers quickly learned from the Native Americans that maize grew better in the area than grain from Europe. Maize can also be grown in fields where tree stumps still stand after clearing. In addition, it matures within three months in the climate of the southern states. The best long-term form of storage for corn that could not be eaten or fed to cattle in time was as whiskey. This can be kept almost indefinitely and also requires significantly less storage space or transport capacity than maize. In view of the difficult transport situation in Kentucky and the remoteness of the area at the time, whiskey was also much more suitable as a commodity than corn. While farmers made about 10 cents on a bushel of corn, the income from whiskey that could be made from it was more than a dollar. In the early days of settlement, whiskey was one of the most important commercial goods alongside flour and hemp and was often used as a substitute currency. The producers were farmers who processed their harvest into whiskey and for whom whiskey distilling was just one of many agricultural activities.

Most whiskey makers of the time used copper stills, which were first imported via the Appalachians and later made by local artisans. For the first firing process, some producers used a hollowed-out tree trunk into which hot steam was directed, which evaporated the alcohol. The second distillation took place in a still, the result was called "Log and Copper Whiskey". According to legend, the first person to produce whiskey in Kentucky was the Baptist preacher Elijah Craig in what is now Bourbon County in 1789 . However, this claim did not appear for the first time until 1874, and whiskey production can now also be proven in the 1770s. Kentucky colonists first grew corn in the early 1770s. The legend of Elijah Craig as the first bourbon manufacturer probably spread in times of a growing abstinence movement , when a Christian preacher as the forefather of Bourbon was supposed to refute the moral arguments of the often Christian abstainers. Kentucky developed a lively distillery landscape, with numerous farmers selling their corn and other grains for further processing. Kentucky whiskey had a good reputation even before the American Civil War and was known as "Bourbon County Whiskey". The alcohol was distilled from everything that was available - mostly corn, but also other grains such as rye or fruits such as apples and peaches. The whiskey, which was produced west of the Appalachian Mountains at the end of the 18th century / beginning of the 19th century, was not matured and stored, but bottled and drunk immediately after distillation. In appearance and aroma it was more like vodka than today's whiskey. The practice of storing whiskey for several years to improve the aroma did not develop until the middle of the 19th century in the southeastern United States.

Origin of the typical bourbon in the early 19th century

The exact origins of bourbon can no longer be reconstructed today. The development took place in the first years of settlement, when many farmers and distillers were largely left to their own devices, produced little or no written documents, and transport and communication routes to the more organized eastern US were difficult. Especially in times of the abstinence movement and prohibition at the beginning of the 20th century, municipalities and regions tried to downplay their connection to early alcohol production and destroyed numerous historical documents in the process.

At the beginning of the 19th century, whiskey began to gain popularity outside of its core region. Trade disputes with temporary embargoes hindered the trade in molasses , the raw material for rum, and the abolition of the international slave trade in 1808 permanently restricted the supply of sugar cane, so that rump prices rose. Production in Kentucky began to focus on distilleries, of which there were between 2000 and 7000 by 1810. Kentucky whiskey and western whiskey were names for whiskey on the east coast at the time.

Before the American Civil War, there were two processes that distinguished bourbon whiskey from other American whiskeys: on the one hand, storage in charred oak barrels and, on the other hand, fermentation with sour mash, i.e. fermentation begins with mash that was obtained through a previous fermentation process , similar to sourdough . It has been known at least since ancient times that storage in charred oak barrels makes alcohol more durable. The distillers of Bourbon Counties probably adopted the technology from rum makers in the West Indies , who already stored their rum in similar barrels to make it more aromatic. Sour mash fermentation was developed by James C. Crow , probably by starting fermentation with lees of beer rather than fresh yeast. In addition to yeast, this also contained lactic acid bacteria and gave the whiskey a special aroma. Crow, who was trained as a doctor and chemist in Scotland, was the first master distiller who tried to use scientific methods to gain detailed control over the brewing and distilling process and to pay close attention to hygiene in the manufacturing process. Old Crow whiskey spread throughout the United States and was a well-known high quality whiskey by the end of the 19th century. Over time, distilleries outside of Bourbon Counties and Kentucky began using these methods of production; Bourbon whiskey became the stylistic term for a certain type of whiskey.

The first industrial distillery opened in Louisville, Kentucky in 1816. Hope Destilling, registered in New England, invested $ 100,000 in capital in 100 acres of land and machines that could do the job of 30 men. Their stills were made of 10 tons of copper and produced enough waste from whiskey production to feed 5,000 pigs. However, the market was not yet big enough and Hope Destilling gave up the business again after a few years. The proliferation of the railroad in the United States in the first half of the 19th century was a major contributor to Kentucky whiskey spreading across the United States.

American Civil War and Gilded Age

The time during and immediately after the war damaged the distilleries. Some were destroyed in the American Civil War, while others suffered from problems from disrupted transportation and trade routes. Abraham Lincoln introduced a liquor tax in 1862 to finance the war, which in particular drove smaller distilleries to bankruptcy in the years that followed. In the industry there was a change to larger, more modern distilleries, which mostly worked with continuous stills ( coffey stills ) and had enough financial reserves to advance the money for the tax. Bourbon production expanded after the war when colonization of the American West began. The first distilleries began to industrialize to meet the increasing demand. The first attempts to regulate bourbon production by law and to set certain standards were made in 1897 with the Bottled-in-bond Act , which guaranteed that whiskey labeled Bonded or Bottled in bond would be under the control of the US government for at least four years matured in certain warehouses and then bottled with 50% alcohol by volume. This regulation should enable conscientious distillers to differentiate their whiskey from other whiskey available on the market. The US Congress passed further laws to define and standardize bourbon in 1907 and 1909. Bottling instead of kegs only began to spread at the beginning of the 20th century, after Michael J. Owens invented the first automatic filling system.

Jewish immigrants

Since the turn of the century 1900, numerous Jewish immigrants participated in the whiskey production. These often found their first mainstay in the United States in the alcohol trade. Some of them went into their own production and founded influential and important distilleries. In the whiskey centers of Louisville , Kentucky, Cincinnati , Ohio, and Chicago , Illinois , they accounted for about a quarter of the total whiskey trade.

Charles Herbst invented Old Fitzgerald whiskey in Louisville , Kentucky in 1870 , and it has been sold in the United States for over 140 years. Isaac Wolf Bernheim , born in Schmieheim (today part of Kippenheim near Freiburg im Breisgau ) founded IW Harper, one of the most influential brands of the prohibition and post-prohibition era. Bernheim sold his company in 1933 to Leo Gerngross and Emil Schwarzhaupt, who in turn sold it to Schenley Industries in 1937 . Schenley was led by Lewis Rosenstiel , who in the following decades became the most influential person in the bourbon industry and, among other things, enforced that the US Congress granted legal protection for bourbon as a designation of origin in 1964 .

Joseph Greenhut , immigrated from Austria at the age of nine, founded the Great Western Distillery in Peoria near Chicago, which at the end of the 19th century was the largest distillery in the world and the founding distillery of the Whiskey Trust . Heaven Hill , now the largest privately owned distillery, was founded in 1934 by the Shapira family: Jews who fled Russia and still own Heaven Hill today. Oscar Getz saved the Tom Moore Distillery from bankruptcy during World War II . The Oscar Getz Museum of Whiskey History in Bardstown , Kentucky goes back to him . Also during the Second World War, co-investor Harry Blum prevented Jim Beam from being sold to Schenley by temporarily taking over the distillery entirely.

In the times before Prohibition, this Jewish connection to whiskey was often misused by anti-Semitic proponents of Prohibition for propaganda. Henry Ford , an outspoken anti-Semite and opponent of alcohol, railed against the distillery, "which is on the long list of American industries that was ruined by the Jewish monopoly." Louisville and Cincinnati are thoroughly Jewish cities that are no longer American.

Prohibition and aftermath

Bourbon was the best-selling spirit in the United States until Prohibition , but has lost its importance since then. The first US states began banning alcohol production in the early 20th century. From 1913 there was a ban on delivering whiskey to the "dry" states. Prohibition began throughout the US in 1920 and lasted until 1933. Individual states banned alcohol longer; Alcohol consumption is still banned in individual counties and communities. During the prohibition era, many distilleries had to go out of business. Six distilleries (A. Ph. Stitzel, Glenmore, Schenley, Brown-Forman, National Distillers and Frankfort Distilleries) were licensed to supply pharmacies with medicinal whiskey , which they could only dispense against a prescription.

Although the importance of hard alcohol increased compared to wine and beer, since more alcohol could be transported and hidden there in less volume, but the bourbon could not benefit from this. Above all, the importance of smuggled Canadian whiskey, which tastes much milder, and of home-made gin in the USA increased. After the end of Prohibition, it also took a few years before newly matured bourbon whiskey came back on the market in larger quantities. After Prohibition, American consumers got used to the milder taste of Canadian whiskey and gin and stuck with these drinks, so that bourbon could no longer achieve its pre-Prohibition importance and in the long term lost its importance compared to rum and vodka. Immediately after the end of Prohibition, many sales and supply chains collapsed and had to be rebuilt. Experts and their specialist knowledge had migrated to other industries. The surviving American distilleries ran out of stocks and took a few years to mature bourbon again. Canadians and Scots used these years to gain market share with their whiskey and then to hold it. After the industry had just repositioned itself in the early 1940s, the US was part of World War II after the attack on Pearl Harbor and the distilleries were required to produce industrial alcohol for use by the military. Hard alcohol for drinking was again imported from other countries. Above all, the rum industry in the Caribbean was able to benefit from this, as it had enough supplies without any problems and also gained market share. The US distilleries tried to counteract this by producing blended whiskey - whiskey that is blended with pure alcohol and flavorings. In doing so, however, they accustomed the public to this form of drink and gained a reputation for not making whiskey of particularly high quality.

Boom in the post-war years and market collapse

Bourbon production increased in the following decades. In the US during the Cold War , bourbon was a "patriotic drink". In the wake of the soldiers of the US Army, Bourbon spread internationally and was able to open up other markets. In particular, Jim Beam and Jack Daniels managed to market themselves internationally. The rise of the two brands to become the leading bourbon brands occurs in the late 1950s.

While Brenner had to pay tax on their whiskey after eight years at the latest, the Forand Bill passed in 1959 postponed this period to 20 years. Distilleries could now store whiskey for 12 or 15 years without having to spend a lot of money on taxes years before, and they are now also bringing whiskey with longer storage times onto the market. This enabled them to significantly expand their product range. At the same time they expanded their marketing range. In particular, so-called "holiday packages" with specially designed bottles and often with the addition of carafes and glasses conquered the market. In 1964 a lobby group around Lewis Rosenstil was able to enforce that bourbon was legally protected in the USA, so that they no longer had any competition from foreign bourbon producers.

After the producers filled the warehouses with full production in the 1960s, the market collapsed in the late 1960s. The younger generation wanted to distance themselves from their parents' tastes and drank beer and wine, vodka and tequila. The whiskey manufacturers sat on large storage capacities that they could not get rid of and had to sell them at competitive prices. Since the 1970s, numerous manufacturers went bankrupt or were bought up by more financially strong international corporations. Only in the southern states was the bourbon able to maintain its position. In the beverage industry, these are known as the “Bourbon Belt”. However, this was and is too small to compensate for national trends.

US-wide, bourbon sales only recovered in the 1990s, reaching sales figures since 2010 that were last seen before Prohibition. Scottish distilleries first began to respond to the general trend towards lower alcohol consumption by bringing higher quality, higher priced, premium products to the market. These single malts were a huge hit, and American distilleries began developing similar whiskey. Although it has long been customary to fill only whiskey from a barrel in a bottle of single malt was similar concept of Single Barrel (single barrel) than in 1984. Blanton's was introduced Bourbon with that label.

Renaissance in the 21st century

The small batch (small amount) developed from the single barrel . Jim Beam introduced the so labeled Booker's Bourbon as a small batch . According to Jim Beam's definition, this is bourbon from a few selected places in the warehouse, where experience has shown that the whiskey matured particularly well. There weren't many of these, so the distillery only produced a small amount. Later, smaller distilleries followed, which referred to their entire production as small batches , since these are only available in small quantities anyway. The term is still not legally defined, but it is widely used in marketing. Julian Van Winkle , grandson of Pappy Van Winkle, established extra long stored bourbons from the market. He bought selected barrels from other distilleries. The Pappy Van Winkle Family Reserve has matured for over 20 years, won numerous awards and is now the most expensive bourbon on the market. At auctions, individual bottles are often traded for four-digit amounts. Other distillers followed suit and brought bourbon on the market that had matured for more than 12 years.

In 2007, 90% of the bourbon whiskey produced worldwide - with the exception of Tennessee whiskey - was produced by twelve distilleries, all of which were in the bluegrass region of northern Kentucky. The total export of spirits from the USA reached a volume of 1.01 billion US dollars, of which bourbon accounted for 713 million US dollars.

Bourbon whiskey, like Scotch whiskey, has had an upswing since the 1990s with the advent of expensive premium products such as Maker's Mark or Woodford Reserve . At the beginning of the 21st century, bourbon sales were as high as they were at the beginning of Prohibition. While bourbon whiskey can theoretically be made anywhere in the United States, ten of the eleven major bourbon makers are based in Kentucky. The only exception is A. Smith Bowman , who is based in neighboring Virginia. All these manufacturers now belong to multinational corporations. Since the 1990s, there has been a trend towards smaller independent manufacturers , similar to microbreweries .

Bourbon has seen a sharp rise especially since 2010. Kentucky's gross domestic product from whiskey rose from $ 1.8 billion in 2012 to $ 3 billion in 2014. In the years after 2010, several new large distilleries opened and the number of employees in the industry rose in Kentucky from 8,600 in 2012 to 15,000 in 2014.

Distilleries

Since the turn of the millennium, there has been a developing scene of numerous microdistilleries. From 2007 to 2013 alone, their number in the United States rose from under 100 to over 400, and by the end of 2014 it was 600. The so-called rectifyers , who do not distill themselves, but buy whiskey in large quantities on the market, possibly again, play a special role filter, then store it again in its own barrels according to its own process and blend it and then sell it under its own brand name. In terms of quantity, however, almost all of the bourbon comes from a few large distilleries in Kentucky, most of which have existed for several decades. The entire craft scene had a market share of around 1% in 2014.

| image | Surname | owner | Location | Former names | Brands | Remarks |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A. Smith Bowman | Sazerac Company | Fredericksburg , Virginia | Virginia gentleman | Second fire and storage only. The first fire takes place at Buffalo Trace. The only major distillery outside of Kentucky. | ||

| Barton 1792 Distillery | Sazerac Company | Bardstown , Kentucky | Tom Moore Destillery, Barton Brands, | Kentucky Gentleman, Ridgemont Reserve 1792, Ten High, Very Old Barton | The Oscar Getz Museum of Whiskey History goes back to a former collection of the distillery owner. | |

| Booker Noe Distillery | Beam Suntory | Boston , Kentucky | Churchill Distillery | Jim Beam | Industrial facility without a visitor center, mainly producing Jim Beam White Label, | |

| Buffalo Trace | Sazerac Company | Frankfort , Kentucky | OFC Distillery, George T. Stagg Distillery, Ancient Age, Blanton's | Buffalo Trace, Van Winkle Family Reserve , Old Charter, Blanton's Single Barrel, Elmer T. Lee Single Barrel, Eagle Rare, Ancient Age, McAfee's Benchmark, Virginia Gentleman (first brand) | National Historic Landmark . Was allowed to continue producing during Prohibition. | |

| Early Times Distillery | Brown forman | Shively , Kentucky | Brown-Forman Distillery, Old Kentucky Distillery | Early Times, Old Forester | Was allowed to continue producing during Prohibition. | |

| Four roses | Kirin Company | Lawrenceburg , Kentucky | Old Prentice | Four Roses, Bulleit (under contract for Diageo ) | Listed on the National Register of Historic Places | |

| George Dickel | Diageo | Cascade Hollow , Tennessee | George Dickel | Tennessee whiskey. | ||

| Heaven Hill | Family property | Lexington , Kentucky / Bardstown, Kentucky / Louisville , Kentucky | Bernheim (in Lexington) | Evan Williams , Elijah Craig, Fighting Cock, Heaven Hill, Old Fitzgerald, Cabin Still, Rebel Yell (under contract with Luxco ). Ezra Brooks (under contract for Luxco) | Distillation in Lexington, storage, bottling and visitor center in Bardstown. Largest independent spirits producer in the USA. All previous Master Distillers came from the Jim Beam family. | |

| Jim Beam | Beam Suntory | Clermont , Kentucky | Jim Beam, Jakob's Well, Knob Creek, Old Crow | Show distillery with a visitor center in which, in addition to Jim Beam and Jim Beam White Label, most of the group's other brands are also distilled. | ||

| Jack Daniel's | Brown forman | Lynchburg , Tennessee | Jack Daniel's, gentleman Jack | Tennessee whiskey. | ||

| Maker's Mark | Beam Suntory | Loretto , Kentucky | Maker's Mark | National Historic Landmark | ||

| MGP Distillery | MGP Ingredients | Lawrenceburg , Indiana | Rossville Distillery, Seagramm's Distillery, Lawrenceburg Distillers Indiana (LDI) | No own brands. | Manufactures whiskey for other brands who either fill the product into their own bottles or process and fill them further; for example Bulleit, many “craft” whiskeys. | |

| Wild Turkey | Davide Campari-Milano | Lawrenceburg, Kentucky | Wild Turkey |

As a result of the bourbon boom since the beginning of the 21st century, several large distilleries have been added in the years since 2010, some of which are already in production and some of which are in the process of establishing production.

| image | Surname | owner | Location | Former names | Brands | Remarks |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Benjamin Prichard's | Family property | Kelso , Tennessee | Benjamin Prichard's Tennessee Whiskey | Production started in 2000. Tennessee whiskey that does not have to go through the Lincoln County Process due to an exception to the law. | ||

| Bulleit | Diageo | Shelby County , Kentucky | Bulleit | Opening planned for 2016. Planned production capacity is below what Bulleit whiskey is already being sold. | ||

| Limestone Branch | Family owned / Luxco (50% each) | Lebanon , Kentucky | Yellowstone | Start of production in 2012. | ||

| Michter's | Chatham's import | Shively, Kentucky | Michter's | Start of production planned for 2015. Historic brand name from Pennsylvania. Except for the brand, the new Michter's Distillery has no connections to the former Michter's. | ||

| Willett | Family property | Bardstown, Kentucky | Willett Pot Still Reserve, Willett Family Estate Bottled Bourbon and Rye, Noah's Mill, Rowan's Creek, Johnny Drum, Old Bardstown, Pure Kentucky, and Kentucky Vintage | From 1936 to the 1970s it was the seat of a distillery in the same family. Reopening in 2012. | ||

| Woodford Reserve | Brown forman | Versailles , Kentucky | Labrot and Graham, Old Oscar Pepper Distillery | Woodford Reserve | Distillery much older, but out of order for several decades. Production started in 1996. National Historic Landmark |

use

In addition to being used as a drink, bourbon is also used in cooking. Bourbon is a widespread ingredient in various sauces and glazes, especially in the cuisine of the southern states . It's an ingredient in sweet potato casseroles and bread puddings and in bourbon balls .

Numerous cocktails are classically mixed with rye whiskey or bourbon, for example Mint Julep , Old Fashioned , Whiskey Toddy , Whiskey Sour and Manhattan . It often pairs with another common drink from the southern states, namely cola in the long drink whiskey-cola .

reception

While many writers wrote about alcohol, southern writers almost always had bourbon whiskey as their subject. William Faulkner drank lots of whiskey of all kinds, but his favorite was bourbon, often as a mint julep . It is still a custom today to take a sip of bourbon at one's grave and leave the opened bottle at the grave. Irvin S. Cobb , a Louisville journalist who wrote the Sourmash column in the local magazine for years , published Red Likker, the first novel in 1929 to deal with the great Bourbon dynasties of Kentucky. In Bardstown , Kentucky is the Oscar Getz Museum of Whiskey History .

Well-known bourbon drinkers from film and television were JR Ewing from the television series Dallas , who regularly ordered Bourbon and Branch (bourbon with water), Gene Hackman , who tries to order various bourbons in French in Paris in French Connection II , and James Stewart who is in Isn't Life Beautiful? indicating the extent of his despair by ordering a double bourbon .

In Westerns , whiskey is a standard drink. In the times of the Wild West , however, everything with a high alcohol content was often sold as whiskey. The whiskey itself mostly came from distilleries in Kentucky, Tennessee or Illinois, was bourbon or rye whiskey, but was usually stretched, flavored and mixed with other alcohol on the way west, so that the inhabitants of the west, like the cowboys, probably did not have a real one Drank bourbon.

marketing

With the renaissance of bourbon, Kentucky and Tennessee developed their own whiskey tourism. Many distilleries, now also industrial companies, offer visitor centers and tours. Microdistilleries in particular often succeed in making more money with these visitor centers and the associated shop than with the actual whiskey sale. In addition to the Kentucky Bourbon Trail with 2.5 million visitors from 2008 to 2013, there is also the Kentucky Bourbon Festival , which takes place annually in Bardstown, Kentucky.

literature

- CK Cowdery: Bourbon, Straight - The Uncut and Unfiltered Story of American Whiskey. Made and Bottled in Kentucky, Chicago, Illinois 2004, ISBN 0-9758703-0-0 .

- Henry G. Crowgey: Kentucky Bourbon: The Early Years of Whiskeymaking University Press of Kentucky, 2013, ISBN 978-0-8131-4417-7 .

- Gilbert Delos: Les Whiskeys du Monde. Translation from French: Karin-Jutta Hofmann: Whiskey from all over the world. Karl Müller, Erlangen 1998, ISBN 3-86070-442-7 , pp. 124-147.

- Gary Regan, Mardee Haidin Regan: The Book of Bourbon . Jared Brown, 2009, ISBN 978-1-907434-09-9 .

- Michael R. Veach: Kentucky Bourbon Whiskey: An American Heritage University Press of Kentucky, 2013, ISBN 978-0-8131-4165-7 .

Web links

Remarks

- ^ Alan J. Buglass (Ed.): Handbook of Alcoholic Beverages: Technical, Analytical and Nutritional Aspects. John Wiley & Sons, 2011, ISBN 978-0-470-97665-4 , p. 519.

- ↑ a b c d e f g Alan J. Buglass (Ed.): Handbook of Alcoholic Beverages: Technical, Analytical and Nutritional Aspects. John Wiley & Sons, 2011, ISBN 978-0-470-97665-4 , p. 522.

- ^ Alan E. Fryar: Springs and the Origin of Bourbon ( Memento of the original from September 3, 2013 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was automatically inserted and not yet checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. . In: GROUND WATER. No. 4, July-August 2009, p. 605.

- ^ A b Alan J. Buglass (Ed.): Handbook of Alcoholic Beverages: Technical, Analytical and Nutritional Aspects. John Wiley & Sons, 2011, ISBN 978-0-470-97665-4 , p. 520.

- ↑ Chuck Cowdery: Flavoring Is Legal in American Whiskey. Yes, You Read That Correctly , The Chuck Cowdery Blog September 16, 2014

- ↑ a b c d e f g Alan J. Buglass (Ed.): Handbook of Alcoholic Beverages: Technical, Analytical and Nutritional Aspects. John Wiley & Sons, 2011, ISBN 978-0-470-97665-4 , p. 521.

- ↑ Laura Kiniry: Where Bourbon Really Got Its Name and More Tips on America's Native Spirit . In: Smithsonian Magazine. 13th June 2013.

- ↑ a b c Alan J. Buglass (Ed.): Handbook of Alcoholic Beverages: Technical, Analytical and Nutritional Aspects. John Wiley & Sons, 2011, ISBN 978-0-470-97665-4 , p. 523.

- ↑ CK Cowdery: Bourbon, Straight - The Uncut and Unfiltered Story of American Whiskey. Made and Bottled in Kentucky, Chicago, Illinois 2004, ISBN 0-9758703-0-0 . P. 8

- ^ A b Franz Brandl : Whisk (e) y . Südwest-Verlag, Munich 2013, ISBN 978-3-517-08335-3 , p. 190

- ↑ Erica Peterson: Is Kentucky Limestone Water Indispensible for Bourbon? In: WFPL News. November 27, 2013.

- ↑ a b c d e Alan E. Fryar: Springs and the Origin of Bourbon ( Memento of the original from September 3, 2013 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. . In: GROUND WATER. No. 4, July-August 2009, p. 606.

- ↑ a b c d Alan J. Buglass (Ed.): Handbook of Alcoholic Beverages: Technical, Analytical and Nutritional Aspects. John Wiley & Sons, 2011, ISBN 978-0-470-97665-4 , p. 525.

- ↑ a b c d e f g Charles K. Cowdery: Bourbon. In: John T. Edge (Ed.): The Encyclopedia of Southern Culture. Vol. 7: Foodways. University of North Carolina Press, 2007, ISBN 978-0-8078-5840-0 , p. 127.

- ^ A b Inge Russell, Graham Stewart: Whiskey: Technology, Production and Marketing. Elsevier, 2014, ISBN 978-0-12-404603-0 , p. 200.

- ^ A b c Inge Russell, Graham Stewart: Whiskey: Technology, Production and Marketing. Elsevier, 2014, ISBN 978-0-12-404603-0 , p. 46.

- ↑ CK Cowdery: Bourbon, Straight - The Uncut and Unfiltered Story of American Whiskey. Made and Bottled in Kentucky, Chicago, Illinois 2004, ISBN 0-9758703-0-0 . P. 17

- ↑ Gary and Mardee Regan: Bourbon. In: Andrew F. Smith (Ed.): The Oxford Companion to American Food and Drink. Oxford University Press, 2007, ISBN 978-0-19-530796-2 , p. 60.

- ^ A b C. K. Cowdery: Bourbon, Straight - The Uncut and Unfiltered Story of American Whiskey. Made and Bottled in Kentucky, Chicago, Illinois 2004, ISBN 0-9758703-0-0 . P. 2

- ↑ a b c d e f g h i Gary Regan, Mardee Haidin Regan: The Book of Bourbon . Jared Brown, 2009, ISBN 978-1-907434-09-9 '

- ^ A b Henry G. Crowgey: Kentucky Bourbon: The Early Years of Whiskeymaking. University Press of Kentucky, 2013, ISBN 978-0-8131-4417-7 .

- ^ Alan E. Fryar: Springs and the Origin of Bourbon ( Memento of the original from September 3, 2013 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was automatically inserted and not yet checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. . In: GROUND WATER. No. 4, July-August 2009, p. 607.

- ↑ Michael R. Veach: Kentucky Bourbon Whiskey: An American Heritage. University Press of Kentucky, 2013, ISBN 978-0-8131-4165-7 , p. 19.

- ↑ CK Cowdery: Bourbon, Straight - The Uncut and Unfiltered Story of American Whiskey. Made and Bottled in Kentucky, Chicago, Illinois 2004, ISBN 0-9758703-0-0 , p. 110

- ^ A b Charles K. Cowdery: Bourbon. In: John T. Edge (Ed.): The Encyclopedia of Southern Culture. Vol. 7: Foodways. University of North Carolina Press 2007, ISBN 978-0-8078-5840-0 , p. 128.

- ↑ a b c d e Gary and Mardee Regan: Bourbon. In: Andrew F. Smith (Ed.): The Oxford Companion to American Food and Drink. Oxford University Press, 2007, ISBN 978-0-19-530796-2 .

- ↑ a b c d Reid Mitenbuler: The Jewish Origins of Kentucky Bourbon. In: The Atlantic . May 12, 2015.

- ^ A b C. K. Cowdery: Bourbon, Straight - The Uncut and Unfiltered Story of American Whiskey. Made and Bottled in Kentucky. Chicago, Illinois 2004, ISBN 0-9758703-0-0 , p. 152.

- ↑ CK Cowdery: Bourbon, Straight - The Uncut and Unfiltered Story of American Whiskey. Made and Bottled in Kentucky. Chicago, Illinois 2004, ISBN 0-9758703-0-0 , p. 151.

- ↑ a b c d Charles K. Cowdery: Bourbon. In: John T. Edge (Ed.): The Encyclopedia of Southern Culture. Vol. 7: Foodways. University of North Carolina Press 2007, ISBN 978-0-8078-5840-0 , p. 129.

- ^ A b C. K. Cowdery: Bourbon, Straight - The Uncut and Unfiltered Story of American Whiskey. Made and Bottled in Kentucky, Chicago, Illinois 2004, ISBN 0-9758703-0-0 . P. 58

- ↑ Michael R. Veach: Kentucky Bourbon Whiskey: An American Heritage University Press of Kentucky, 2013, ISBN 978-0-8131-4165-7 , p. 106

- ↑ Michael R. Veach: Kentucky Bourbon Whiskey: An American Heritage University Press of Kentucky, 2013, ISBN 978-0-8131-4165-7 , p. 105

- ↑ Michael R. Veach: Kentucky Bourbon Whiskey: An American Heritage University Press of Kentucky, 2013, ISBN 978-0-8131-4165-7 , p. 107

- ↑ Michael R. Veach: Kentucky Bourbon Whiskey: An American Heritage University Press of Kentucky, 2013, ISBN 978-0-8131-4165-7 , p. 110

- ↑ Michael R. Veach: Kentucky Bourbon Whiskey: An American Heritage University Press of Kentucky, 2013, ISBN 978-0-8131-4165-7 , p. 111

- ↑ a b Gary and Mardee Regan: Bourbon. In: Andrew F. Smith (Ed.): The Oxford Companion to American Food and Drink. Oxford University Press 2007, ISBN 978-0-19-530796-2 , p. 62.

- ↑ Michael R. Veach: Kentucky Bourbon Whiskey: An American Heritage University Press of Kentucky, 2013, ISBN 978-0-8131-4165-7 , p. 118

- ↑ David A. Mann: Gov. Beshear: "The bourbon boom is real and producing results for all Kentuckians." , Louisville Business First, Oct. 21, 2014

- ^ Inge Russell, Graham Stewart: Whiskey: Technology, Production and Marketing. Elsevier, 2014, ISBN 978-0-12-404603-0 , p. 43.

- ↑ a b Saabira Chaudhuri: 'Craft' Bourbon Is in the Eye of the Distiller , The Wall Street Journal August 28, 2015

- ↑ created by Medley in Lebanon, Kentucky. See Delos: Whiskey from all over the world. P. 145.

- ↑ Chuck Cowdery : Diageo's New Distillery to Bear Bulleit Name , the Chuck Cowdery Blog August 21, 2014

- ^ Brian Carpenter: Bourbon. In: Joseph M. Flora, Lucinda Hardwick MacKethan, Todd W. Taylor (Eds.): The Companion to Southern Literature: Themes, Genres, Places, People, Movements, and Motifs. LSU Press, 2002, ISBN 0-8071-2692-6 .

- ↑ CK Cowdery: Bourbon, Straight - The Uncut and Unfiltered Story of American Whiskey. Made and Bottled in Kentucky, Chicago, Illinois 2004, ISBN 0-9758703-0-0 , p. 78

- ^ Inge Russell, Graham Stewart: Whiskey: Technology, Production and Marketing. Elsevier, 2014, ISBN 978-0-12-404603-0 , p. 45.