Pamir (ship)

|

The Pamir under full gear and Finnish flag (date unknown)

|

||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||

The Pamir was a four-masted barque (four-masted sailing ship) built in 1905 for the Hamburg shipping company F. Laeisz . It was one of the Flying P liners, famous for its speed and reliability, and was traditionally christened with a name beginning with "P", that of the Central Asian Pamir Mountains .

In 1932 she won the Wheat Regatta , a race between tall ships on a cargo voyage from Australia to Europe. In 1949 the Pamir was the last tall ship to circumnavigate Cape Horn without an auxiliary engine on a cargo voyage ( Cape Hornier ). In the 1950s, it was, like the Passat , as a freight-moving sail training ship for the German merchant navy used. The two ships were the last tall ships to carry freight in Germany and (with the Omega ) were among the last three tall ships to sail in the world.

The Pamir sank in a hurricane on September 21, 1957 . 80 of the 86 crew members, including many young cadets, were killed. The sinking and the subsequent rescue operation received a lot of attention in the international media. The cause of the accident is still controversial today: The Lübeck Maritime Administration decided on incorrect stowage of the barley load , the delayed reduction of the sail area in the storm and incoming water through unlocked ship openings. Otto Hebecker, the expert commissioned by the shipping company for the negotiation, assumed that the Pamir would definitely have sunk in the storm, regardless of the security measures taken by the crew. Hebecker was not heard from chairman Ekhard Luhmann. For his part, the shipping company's lawyer argued in the maritime administration hearing and in a book published in 1991 for the ship to be leaking in a storm.

The loss of the Pamir led to the end of the freight training ships when the Passat was decommissioned just a few weeks later . He also initiated an international tightening of the safety precautions for tall ships and training ships.

The history of the ship

Launching and saltpetre trips

The Pamir was built by the Hamburg shipyard Blohm & Voss under construction no. 180 built as a three-island ship in steel (i.e. the riveted hull and decks were made of steel). On July 29, 1905, after the ship was christened at 3 p.m. in Hamburg, it was launched . At the time, the ship measured 3,020 gross tons , carried up to 4,000 square meters of sails and was put into service by the F. Laeisz shipping company on October 18, 1905 . On October 31, 1905, she left the port of Hamburg on her first voyage to South America under Captain Carl Martin Prützmann, after he had also supervised the construction . 1905-1906 she made two trips from Lizard Point to Valparaiso in 70 and 64 days. She was the smallest and most stable of the last eight four-masted barques built for F. Laeisz, which were called " The Eight Sisters " because of their similar construction plans , but were for the most part not sister ships in the strict sense. Heinrich Horn was the captain from 1908 to 1911.

For nine years the Pamir was used on saltpeter trips to North Chile (South America), on which it transported the then important Chile nitrate - fertilizer and raw material for the manufacture of ammunition - to Europe. During this time she circled Cape Horn eighteen times, which was feared because of its extreme weather conditions . Once, Captain Becker reported to his shipowner that the sailors had asked him to add a woman to the insufficient number of crews, but he refused. The captain would rather sail around Cape Horn with a dangerously reduced crew of 18 men than accept a woman. Normally there were only 32 to 34 men on board on the four-masted barges of the Laeisz shipping company, all of whom were very busy and had to work until they dropped in bad weather. From May 1911 to March 1912 the Pamir ran under the command of Captain R. Miethe, 1912–1913 under Gustav A. H. H. Becker and then until 1914 under Wilhelm Johann Ehlert.

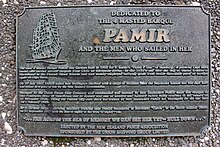

First World War

Started from Hamburg to Valparaiso on March 1st and since July 17th, 1914 homewards from Taltal in Chile, the Pamir met a French sailing ship on September 1st, 1914 at equator height, which was signaling the state of war by means of flag signals . It was not until September 15 that she found out more about the German steamer Macedonia , which she encountered in the North Atlantic at 27 ° N, 32 ° W , which, on its way from New Orleans to Cadiz, had initially presented itself as the Dutch Sommelsdijk II , because of the expected blockade of the English Channel, the Pamir with its crew of 36 men could not safely return to Germany, captain Jürgen Juers brought the ship to the roadstead off Santa Cruz on the Canary Island of La Palma on October 1, 1914 , where one was again with the October 15 Macedonia , which was anchored there, also met there until November 18 , which furthermore caused some diplomatic movements because of its cargo, now regarded by England as "essential to the war effort" (supplier of the Crown Prince Wilhelm, who was converted into an auxiliary cruiser ). According to contemporary witnesses, the most suitable anchorage was made available with the consent of the port administration. Officially, things were negotiated with the help of an interpreter, who was the contact person for the German Africa Service and an employee of the ship agent chosen on site, because the end of the war was to be awaited in Spain, which had been neutral since August 7th. In the course of the following six years, despite minor tensions shortly before the end of the war, a cordial relationship with the local population developed. The memory of the ship and crew is still maintained on La Palma. There are photos in the Archivo General de La Palma , local press reports in the Hemerothek of the Real Sociedad Cosmológica and memorabilia in the Museo Naval . Where the road leads to the harbor area in the south, there is still an "anchor with two shackles" that the crew recovered in early March 1918. On the 60th anniversary of the sinking of the Pamir , a memorial plaque was unveiled in the reception hall of the port building.

It was not until 1920 that the victorious powers allowed the Pamir to transport the still loaded saltpeter to Hamburg before it was to be ceded to Italy as a reparation payment . However, only 17 sailors were left of the crew before the war began, and the ship's equipment was in dire need of repair. The Pamir left Santa Cruz de La Palma on March 4th, 1920 after a farewell party with dignitaries in the Hotel Cuba in the direction of Santa Cruz de Tenerife on Tenerife , where she arrived on March 6th, 1920. With renewed material and a reinforced crew, including several sailors from La Palma and Tenerife, the ship, now dispatched for the trip by the German consul Jacob Ahlers , finally started its onward journey on March 10, 1920 and reached Hamburg on April 10, 1920. Already on April 22nd was the official hearing of the death of two sailors (H. Madsen and A. Grymel) who had gone overboard on the way from Hamburg to Chile. Later in August, during the Priwall's first voyage (started on July 24th, 1920 with 200 men to Chile, in order to provide crews for the Laeisz sailors interned and repatriated), Captain Juers did not take La Palma with a greeting to honor.

The Pamir was delivered to Italy after unloading the cargo and the subsequent repair work in “ Stülckens Dock ”. Between July 5 and 7, 1921, she left her berth in Hamburg. Whether it was pulled by tugs to Rotterdam and further into the Mediterranean and hung up in front of Castellammare di Stabia because the Italians are said not to have had any crews to operate a tall ship has not yet been documented. However, according to later press reports, she came back from Genoa.

Between the world wars

In November 1923 the shipping company F. Laeisz, after having in the meantime repossessed the Peiho , Parma , Passat , Pinnas and Peking for amounts between £ 3,000 and £ 30,000 , succeeded in buying back the Pamir for only £ 7,000 . After she was no longer listed in Lloyd's Register from the end of 1918 to February 1924 , the four-masted barque returned to her home port of Hamburg on March 26, 1924 from Genoa under ballast. On the road again from May 12th, she was again used in saltpeter transport between Chile and Europe. When the saltpetre voyages became unprofitable due to the possibility of producing potassium nitrate (using the Haber-Bosch and Ostwald processes ) for nitrogen fertilizers and explosives in Europe, the big sailing ships in this business had come to an end. After receiving approval to use the inner chambers as crew logis in 1927, the Pamir unloaded its last cargo of saltpetre in Bordeaux, France, in 1931 and then arrived under ballast in the port of Hamburg on July 28th .

The Pamir was sold to the shipowner Gustaf Erikson from Mariehamn, Finland ( Åland Islands ) for 60,000 Reichsmarks , and on November 6, 1931, he took possession of it. The Finn was one of the last major sailing ship owners and, thanks to extremely tight calculations, managed to still operate his ships profitably. The radio system was expanded to save the radio operator's costs, and the ships ended up going uninsured because the insurance premiums would have been the purchase price of one or two ships a year.

On November 20, 1931, the Pamir left the port of Hamburg under the Finnish flag and headed for Australia to take over a cargo of wheat and transport it to Europe. In 1932 she won the Wheat Regatta , a race between tall ships on a cargo voyage from Australia to Europe. After several other wheat transports and participation in a total of seven wheat regattas, the Pamir was used from 1937 to transport guano and nickel ore as well as wool, coal and other loads.

Second World War

In 1939 the Soviet Union attacked Finland and imposed a blockade on Finnish waters, whereupon the Pamir was laid up in Gothenburg, Sweden. Immediately after Finland's armistice with the Soviet Union on March 14, 1940, it was able to be put back into motion. She was sailing under ballast to Bahía Blanca , Argentina for a charter job , but by the time she arrived the job had been illegally canceled. The Pamir was then in the roadstead in front of the port of Bahía Blanca, in order to then again carry out two guano transports between the coral islands of the Seychelles in east Africa and New Zealand .

After Finland entered the war on the part of the German Reich in early 1941, Great Britain confiscated all Finnish ships in its territorial waters and asked New Zealand to act accordingly. On August 3, 1941, the Pamir, then led by Captain Verner Björkfelt, was then confiscated as a prize in the port of Wellington (New Zealand) by a New Zealand customs officer . From then on, the barque sailed under the New Zealand flag and became a kind of “maritime mascot ” of the country during the war . During this time, the stern of the ship still bore the name Mariehamn , the name of his last home port. A New Zealand crew arrived in February 1942, and some of the crew from Finland and the Åland Islands stayed on board for the following years. On March 30, 1942, the Pamir left the port of Wellington to carry out transports between New Zealand and the USA for the shipping company Union Steam Ship Company of New Zealand . A total of nine trips to the Pamir took between New Zealand and the United States, she went every 30,000 pounds sterling a win. In addition to the transport business, it served - as it did under the Finnish flag - to train the next generation of sailors.

On a voyage from Wellington to San Francisco, the Pamir encountered a submarine on November 12, 1944 between Hawaii and the west coast of the USA at position 24 ° 31 ′ N , 146 ° 47 ′ W , which was initially heading for the tall ship. Neither submarine nor tall ship showed their nationality, which made it unclear whether it was an enemy. The unarmed Pamir was an easy target, and the crew was already clearing the lifeboats. The then captain Champion wanted to at least try to ram the submarine by changing course if it got a little closer. But two miles away it turned and disappeared. It remained unclear why it neither opened fire nor made friendly contact, especially since, according to US information, no American submarine was in the area at the time - this suggests a submarine flying the flag of Japan, with which New Zealand is in Was at war. One of the attempts to explain it is that the submarine was unprepared - after all, a non-motorized sailing ship can hardly be detected by a sonar . Perhaps the torpedoes were not ready for action and the passing sea would have prevented the use of a deck gun . Another possibility is that the submarine commander voluntarily let the tall ship pull - impressed by its beauty, as popular stories want to know. The submarine is partially identified as the Japanese I-12 under Corvette Captain Kudo Kaneo (工藤 兼 男), who himself was a cadet on a sailing training ship. At least it could explain why the incident could never be confirmed by the Japanese side, since Kudo and I-12 did not return from this trip; I-12 was last sighted on January 5, 1945 and possibly sent a last, no longer clearly understandable radio call about enemy contact on January 15.

After the Second World War

Even after the end of the war, these voyages were continued, although the shipowner Gustaf Erikson asserted his claims on the ship.

In 1947, the Pamir was the oldest ship in Sydney Harbor as the flagship of the regatta that was held for the 111th birthday of the Australian state of New South Wales .

Due to the increasing pressure of competition it was hardly possible to find cost-covering transport orders for the ship at that time. Then the ship received an order to bring a load of wool to London. This was the first time in a quarter of a century that a tall ship was to bring wool from New Zealand around Cape Horn to Europe. On entering British waters (December 1947), the Pamir received a triumphant reception. In London on March 3, 1948 even Princess Elisabeth , later Queen Elizabeth II, and her husband Philip, Duke of Edinburgh , came on board. On April 20, 1948, the Pamir left London again, on May 1, 1948 she sailed from Antwerp to reach the port of Auckland on August 18, 1948 , after having circled the earth once. It was the tenth and last voyage of the Pamirs under the New Zealand flag. On September 27, 1948, the Prime Minister of New Zealand, Peter Fraser, announced that the sailor would be returned to the shipping company of Erikson, who died in 1947. Officially, New Zealand was supposed to compensate for part of the tonnage losses that Finland had suffered in the war.

Finnish flag again, "Rat Ship", to Belgium

On November 12, 1948, the Pamir was ceremoniously placed under the Finnish flag again and under the command of Captain Verner Björkfelt, who had led her to the award-taking and was now to sail back to Europe. Despite the difficult times for sailing cargo ships, the shipping company managed to get another order for a grain load to Europe. The Pamir left Wellington under ballast on January 31st for Port Victoria , where she anchored two miles from land in the bay on March 6th. After the ballast was unloaded, the inspection cleared the ship to be loaded with barley in sacks, whereupon the Pamir and the Passat, which also belongs to the Erikson shipping company, took over their freight for a distillery in Scotland. The last wheat regatta began with the departure of the Pamir on May 28th , and soon got caught in a storm and was overtaken by the Passat . On July 11, 1949 at 1:00 a.m., the Pamir , loaded with 60,000 sacks, circled Cape Horn for the 36th time, making it the last tall ship without an auxiliary engine to circumnavigate the Cape on cargo voyage (so-called Cape Hornier ). On October 2, 1949, she reached Falmouth , which she then left on October 5 for Penarth (Wales), where she finally arrived on October 7 and was then considered a grain depot by the British Ministry of Food for six months. On April 4, 1950, she was moved to the "Rank Mills" in nearby Barry Docks for unloading after the responsible inspectors in Penarth suspected rats on board. When the cargo was unloaded on the Passat , only a single rat was found on board. On April 18, the loading hatches of the Pamir were finally opened for the first time , but in view of the huge number of rats they were closed again immediately. During the emptying, which lasted until May 9, every possible precaution was taken to prevent the rats from getting onto the docks. They were now fought with shovels, dogs and volunteers; after three weeks exactly 4501 adult animals had been shot. Subsequent gasification with hydrocyanic acid brought down a further 3395, a total of 7896 - hundreds of nests with young animals not counted. Penarth was then the last stop on this trip.

For the shipping company Erikson, the operation of both ships was no longer worthwhile. In December 1950, the Pamir was sold to Belgian scrappers (Van Loo shipyard, Antwerp), as was the similarly constructed Passat , which won the last race .

Again under the German flag

In Germany, Captain Helmut Grubbe in particular, who had once worked on the Pamir himself, was now promoting the use of sailing school ships again after the Second World War. He was able to win over the Lübeck shipowner Heinz Schliewen for the idea of maintaining the traditional tall ships Pamir and Passat and at the same time training prospective ship officers on them. Schliewen bought the two ships from the Belgian scrappers on June 1, 1951 and brought them to Kiel, where they arrived on September 25.

The Federal Ministry of Transport had also set up its own “Working Committee on Sailing School Ships”, which worked out contemporary safety principles for the operation of the two four-masted barques. With the support of the federal government, extensive renovation work was carried out, which was primarily intended to ensure the safe operation of the ships, including the installation of a modern radio system. A prime mover was also installed to improve maneuverability and the accommodations were enlarged. The first test drives took place on December 15, 1951. On January 10, 1952, the Pamir set off from Hamburg on her first voyage - with the destination South American east coast. In the Atlantic, however, the engine failed, so that the Pamir had to continue the journey alone under sail. After just two trips to South America, the Pamir was chained by the customs officials in Rotterdam because Schliewen was having financial difficulties. The Schleswig-Holsteinische Landesbank redeemed the Dutch debts so that the Pamir could sail to Hamburg, where she was again seized. In April 1954, the sailor was foreclosed to the main creditor, the Schleswig-Holsteinische Landesbank, for DM 310,000 , before Schliewen declared bankruptcy in May of the same year.

In the meantime, however, 40 German shipowners had come together to form a consortium that wanted to continue providing training on sailing ships and therefore acquired both ships as the Pamir and Passat Foundation in December 1954. This training was partly financed through the freight trust company with grain purchases for Germany. The partner on the Argentine side was the Agencia Marítima Sudocean , a ship broker who, under the direction of Herbert Huthoff and Thilo Martens, also ensured the teams' contacts with the local population.

After another overhaul, the Pamir left the port of Hamburg on February 10, 1955 and was used again for trips to South America. On five trips under Captain Herrmann Eggers, she transported barley from Buenos Aires to Hamburg and also served as a sailing training ship. At this time it was more popular among midshipmen than the Passat .

At the beginning of 1956 the Pamir in Antwerp loaded 2,500 tons of methanol into barrels for one of her trips . While at anchor, the upper yards were removed and stowed on deck to improve the stability (i.e. the righting ability) of the ship. At sea, the low weight of the barrels caused an unusual list in the English Channel due to the lack of ballast, whereupon Captain Eggers decided to let the Pamir enter the English Falmouth , the nearest port, under engine . There it was confirmed by heeling tests that the stability of the ship was severely impaired. Some of the barrels were then left behind and replaced with ballast; the cargo was picked up a little later by the Passat , which went to the same destination. In May 1956 the Pamir was again a guest in Santa Cruz de Tenerife, where she was also visited by descendants of the crew members who remained on the neighboring island of La Palma during the First World War. However, nothing more should come of the promised reunion there next year.

When Eggers could no longer run the Pamir for health reasons in 1957 , Captain Johannes Diebitsch took over command. As a young sailor Diebitsch had already sailed briefly on the ship until it anchored off La Palma in the First World War. Later Diebitsch had worked for years on sailing ships, including as first officer of Germany , the sailing training ship of the Reichsmarine and at the beginning of the 1950s (on October 10, 1953 in Tenerife) as captain of the Xarifa , a three-masted topsail schooner of the Austrian diving pioneer and underwater filmmaker Hans Hass . The captain's license had Diebitch since 1925. 1941 he survived as a pinch officer the sinking of the auxiliary cruiser Kormoran .

The sixth voyage of the Pamir under the ownership of the Foundation led back to Buenos Aires from June 1, 1957 under ballast. The auxiliary engine was used for 346 hours to increase the speed, so that the journey only lasted 25 days. In 1957, the last film recordings of the Pamir were made on board the Norwegian school ship Christian Radich while filming the Cinemiracle film Windjammer .

The downfall

Sequence of events

On August 11, 1957, shortly after 3 p.m., the Pamir under Captain Diebitsch began her return journey from Buenos Aires to Hamburg with a cargo of barley - more than 90% loosely stowed . The ship route followed the usual S-shaped course across the Atlantic, which is faster than a direct route for tall ships due to the trade winds .

On September 21, 1957 the Pamir got into Hurricane Carrie about 600 nautical miles (approx. 1,100 km) west-southwest of the Azores , which after three changes of direction in the previous days suddenly moved directly from the west towards the Pamir . Before enough sails were recovered , the hurricane reached the ship at around 9:30 a.m. local time (12:30 p.m. Greenwich Mean Time / GMT ). The wind increased so strongly that some sails broke and the rest were only cut off (" slaughtered ") from the yards by the regular crew . At 10:36, radio officer Wilhelm Siemers issued an urgency report from position 35 ° 57 ′ N , 40 ° 20 ′ W , in which he asked other ships to provide their position. The Pamir at that time had been about 30 ° list to port side ( "left") and drove without sails in a storm. At 11 a.m. and 11:04 a.m., the Pamir made SOS calls. In these and later radio messages, the Pamir identified itself as "fourmast bark" (German: four-masted barque) because all radio messages were given in English. This was misunderstood at least once as a foremast broken (German: foremast broken) and still leads to erroneous representations that one or even several masts of the ship were broken. In fact, all the masts on the Pamir were up until the end. According to the radio message, however, the ship had lost all sails at 11 a.m. and was listing 35 °. Meanwhile, with wind speeds of 130 km / h, the waves rose 12 to 14 meters. The captain ordered life jackets to be put on. The incline of the Pamir reached 45 °, so that the Rahnocken (yard ends) repeatedly plunged into the high seas. After a radio pause, the Pamir asked for haste in her next SOS call at 11:54, as the ship was in danger of sinking. Three minutes later she radioed that the ship was “making water” (“now speed ship is making water danger of sinking”, for example: “Now hurry up, the ship is making water, danger of sinking”).

The last, no longer decipherable emergency call was sent at 12:03 p.m. The Pamir capsized at about 12 noon : she lay flat in the water for about half a minute. Then she capsized further and swam about 20 to 30 minutes keel up before she sank. Before that, it was no longer possible to launch lifeboats due to the list. Only three damaged lifeboats, which had broken loose before or during the capsizing, drifted in the churned sea. At first at least 30 crew members managed to save themselves in two of the boats. In addition, later reports from survivors of flares from another boat suggest that a third boat may have been manned. Because of their damage, the two witnessed boats had already lost some of their provisions and fresh water before the shipwrecked reached them; the remaining supplies were largely lost in the next few hours when the boats repeatedly capsized due to their damage and the heavy seas. In addition, there were no dry ones on board - i. H. functioning - distress missiles .

As a result, the most extensive search operation that had ever been carried out to rescue shipwrecked people started with great international media interest. 78 ships from 13 countries searched for the missing persons for seven days. From noon on the second day, after the hurricane had died down sufficiently in the disaster area, eleven aircraft supported the search with a total of 550 flight hours. On September 23, at 5:38 a.m., one of the heavily damaged lifeboats with five survivors was found by the New York steamship Saxon . They were later taken over by the US troop transporter Geiger and brought to Hamburg via Casablanca by a US military plane (arrival on September 29). At 1:41 p.m. on September 24, the Absecon , a ship belonging to the US Coast Guard , found another survivor on the railing of an equally badly damaged, full-blown lifeboat. According to his report, more than ten people were still alive in the boat 24 hours earlier. After the rescue of one survivor, 45 and even 71 rescued people were temporarily reported in Germany due to a hearing impairment of a radio operator in the evening before the misunderstanding was cleared up. A third lifeboat, also badly damaged, was found unmanned. On September 25, a variety of wreckage and tied life jackets were discovered in an area five nautical miles in diameter. According to the later investigation of the accident, “traces of human bodies were found in only two of the life jackets (...). Many sharks have been sighted. "

A total of 80 of the Pamir's 86 crew members were killed, including all officers and the master. 51 of the 86 crew members were cadets, a total of 45 crew members were 16 to 18 years old. The registration of the Pamir was deleted from the Lübeck ship register on May 17, 1958 .

Causes of Doom

Although no one survived from the ship's command and thus no one could be directly sued for nautical fault, the sinking of the Pamir was investigated as thoroughly as few other marine accidents. As is customary in such cases, the responsible Maritime Administration took over the processing . As a result, however, criticism of his verdict was voiced, which was mainly brought forward by the lawyer for the shipping company of the Pamir and the Pamir and Passat Foundation ; the lawyer was accused of a lack of objectivity.

The main reason for the controversy is that the Maritime Administration and the proponents of its ruling have cast doubt on the ship's command in the course of the investigation. Critics see this as an accusation against the ship's command, from which no one has survived and therefore no one can defend himself; Accusations are thus defiling the honor of the deceased and, moreover, are not justified in the specific case because the Maritime Administration overlooked facts or did not pay sufficient attention to them.

The motto of the Lübeck maritime office

In his written justification for the maritime official's verdict on the sinking of the Pamir in a public hearing, the chairman, District Court Counselor Ekhard Luhmann, gave several reasons why, in the opinion of the court, the ship could not withstand the storm: the cargo had not been secured, the deep tank was not flooded, the smallest sails were not set and the superstructure was not adequately protected against the ingress of water. The main cause of the sinking of the Pamir , according to the ruling of the Lübeck Sea Office, was the incorrect storage of the 3,780 tons of barley loaded . Instead of the traditional sack stowage, the barley was stored almost entirely loosely, which can be dangerous because barley has the fastest flow rate of all cereals (i.e. it slips the most easily). 254 tons of barley were loaded in sacks and stowed in five layers on the loose barley to prevent it from slipping. This corresponded to the regulations for motor ships at the time, which were also used for the Pamir and Passat . Until a few years earlier, however, sailing ships had never been loaded with bulk cargo. Loading with loose grain only began in 1952 under Schliewen, and at that time the loose grain was also weighed down with larger quantities of bagged goods than in 1957. For example, Captain Niels Jannasch described the Passat , which was owned by the same owner, on the last wheat transport from 1948-49 Australia and 1952 on the first voyage to South America ordered that the bulk cargo was weighed down with up to 20 layers of grain sacks in 1952 - about four times the sack layers on the last voyage of the Pamir . However, the Pamir and Passat had a longitudinal bulkhead that ran through the entire ship and was intended to prevent the cargo from sliding from one side of the ship to the other. On the other hand, at least on the Passat, it was later discovered that the longitudinal bulkhead was not absolutely tight; Loose grain could seep through as a result during a sea voyage.

Due to a strike by the dockers - including the stevedores - in Buenos Aires, the Pamir crew had to load the barley themselves with the help of unskilled Argentine soldiers. In the loading report it was stated that the load had been "stowed away at sea" and that the grain bulkheads had been placed in accordance with regulations; Due to the Pamir's reaction to the cargo, however, the second officer Buschmann, who as cargo officer was responsible for overseeing the stowage, criticized the fact that a steamship would “not leave like this”. In the storm, the cargo shifted so that the ship could no longer straighten up even after the sail area had been reduced. The deep tanks, which are intended as a stability reserve for flooding in the event of a storm, were also loaded with barley. It remained unclear why they were not used despite the barley - that is, flooded in a storm.

The sail area was reduced very late : at wind force 9 and 10, the Pamir was still under a third of its sail area. One possible reason was that the additional speed caused the captain to try to escape the eye of the hurricane. However, ship ports in the storm remained unlocked, which could penetrate water on deck and the list still increased. The Maritime Administration therefore discussed the possibility that the ship's command did not keep themselves informed about the general weather situation and thus found out about Hurricane Carrie too late. In fact, due to Carrie's frequent and sharp changes of direction, not all weather forecasts issued early and continuous hurricane warnings. The Pamir could have received warnings for her trade area one or two days before Carrie passed through . Mainly due to the Pamir's chosen course at that time , the late reduction of the sail area and unlocked ship openings, the question was raised whether the ship's command actually received the early hurricane warnings. Since only crew members of lower rank survived, this could no longer be determined. In any case, the lower crew and the galley , which has to prepare especially for a storm, were not informed of the approaching hurricane.

The course of the Pamir both before the arrival of the hurricane and in the last hours before its sinking was discussed in detail by the Maritime Administration: In its final days, the Pamir ran a northerly course that took it over the path of the hurricane and ultimately very close to the eye of the hurricane led. However, the Pamir moved from the right to the left side of the hurricane path - it is considered less dangerous because on it the rotation speed of the (left-turning) hurricane is reduced by the pulling movement of the hurricane (" navigable quarter "). Since Carrie changed direction several times and none of the ship's command survived, it is no longer possible to judge today whether the optimal decision was made between crossing the hurricane path and moving as quickly as possible from the hurricane center (change of course to the east or south-east) based on the weather information actually available on board . In retrospect, the choice of ship's command was disastrous because Carrie ultimately moved closer to the ship's location than originally expected and because, for once, Carrie's wind speeds were highest on the left side of the track due to an irregularity in the center of the hurricane that the Pamir could not foresee.

Regarding the ship's course during the hurricane, the Maritime Administration noted that the Pamir maintained her north course without adapting it to the change in the wind direction. Initially, the ship therefore ran off the wind ("tail wind"), but later the wind and the swell came increasingly from the side and finally diagonally from the front, which increased the list of the Pamir . Here, too, due to the lack of witnesses, no statement could be made as to the reason for which the ship's command set the course.

Finally, the suitability of the regular crew was also discussed: although Captain Diebitsch had a lot of sailing experience, he was probably not very familiar with the sailing and stability characteristics of the Pamir . The first officer had only limited sailing experience, as crew with tall ship experience were no longer so easy to find in the 1950s. And the First Boatswain was already 68 years old and - according to statements by a survivor, which was later withdrawn - sick, so that he had to rely on outside help in the last hours of the Pamir .

According to the ruling of the Lübeck Maritime Administration on January 20, 1958, Hurricane Carrie was at most an indirect trigger for the sinking of the Pamir : Without “human error”, which led to the above-mentioned problems, the Pamir would have winds of up to in the opinion of the Maritime Administration can withstand up to 100 knots (185 km / h) - speeds that the hurricane did not reach in the opinion of the Maritime Administration.

Controversy of the lawyer at the time: Leak strike

Maritime law attorney Horst Willner , who represented the shipping company of the ship ( Reederei Zerssen in Kiel) and the Pamir and Passat Foundation in the course of the maritime investigation , came to a different conclusion than the Lübeck Maritime Administration in his 1991 book Pamir: Your Downfall and the Mistakes of the Maritime Authority in his saying. In Willner's opinion, the Pamir probably went under because it had leaked as a result of the enormous loads on the hull in the hurricane . Willner assumes that the riveted hull of the Pamir was repaired with welding work during the overhauls in the 1950s and therefore became more vulnerable. As evidence for his leak theory, he cites, among other things, that according to statements by survivors in some parts of the hull that could not have been exposed to any overflowing water, the water was still up to the door handle. A survivor also reported noises from the ship's hull that indicated a water ingress. The testimony of a survivor that a yellowish-colored fountain of air escaped with a whistling noise from the overturned hull before the sinking is seen by Willner as evidence of the damage to the hull, from which air mixed with pieces of barley flowed. According to Willner, the time between capsizing and sinking of the Pamir was too short for a ship without hull damage. The investigations and statements of Otto Hebecker, a teacher at the former seafaring school in Hamburg as well as an employee of the shipbuilding research institute and at that time an officially recognized expert on questions of ship stability and strength for more than 30 years should not go unmentioned . Hebecker had already at the end of 1957, d. H. Even before the start of the Lübeck Maritime Office negotiation, he was suspected of having had a leak on the Pamir's hull.

Willner criticizes the ruling of the maritime office as biased: The verdict was already fixed before the trial. The Maritime Administration had more interest in acquitting those responsible on land than clearing up the sinking.

Willner also criticized that the Seeamt no square rigger sojourner captain. The decision of the Maritime Office was made by motor ship captains who did not sufficiently appreciate the special conditions of a tall ship; Reports from square sail captains were not taken into account. The Maritime Administration did not take into account the special wind conditions of Hurricane Carrie, which changed direction several times. The captain of the Pamir had chosen the usual setting of sails and the correct direction of travel to move away from the hurricane; It was only through the extreme and unusual changes of direction, after which the eye of the storm moved directly towards the Pamir , that the captain's measures would not have achieved their goal. Another allegation is that the Maritime Administration did not allow the widow of the last captain of the Pamir to be heard, although it would have been at its discretion; In 1985 the rules of procedure were changed so that the widow would have the right to be heard under the current rules.

Willner is accused of not being neutral as a former representative of the shipping company and of having an interest in acquitting the ship's management and shipping company of causing the loss.

In terms of content, Willner was countered that there was no firm evidence of a leak from the Pamir : the hull of the ship had been regularly examined in the years before the sinking and repaired if necessary. There is no evidence that the Pamir's hull was actually later welded rather than riveted; In any case, a mixture of the procedures would not necessarily be problematic, since many ships with partly riveted and partly welded sections sailed the oceans without incident. The water that penetrated could also be explained by the fact that not all ship openings were closed. The air fountain from the capsized ship - documented by only one eyewitness - could also have been caused by the fact that the hull was only damaged during the capsizing. And a certain time between overturning and sinking could hardly be determined due to the prevailing hurricane, since the rigging of the ship beneath the surface of the churned sea could have caused incalculable damage even in a relatively short time.

Some of Willner's opponents therefore consider his view to be wrong, while other critics rate it as possible in principle, but not provable.

Argument from both sides: the Passat was near miss

Both sides also argued that the almost identical Passat survived a severe storm just a few weeks after the Pamir sank and was able to call at a port of refuge, although it was also very badly listed after its barley load slipped. However, shortly before the Passat - i. H. at sea - the cargo has been trimmed; during the storm it flooded a deep tank (which had also been partially filled with barley), and it had reduced its sail area early on.

The Lübeck Maritime Office interpreted the incident on the Passat as an indication that the Pamir would actually have been up to the storm. The lawyer Willner, however, brought up the case to argue that only a leak blow could have caused the sinking of the Pamir .

Causes of the low number of survivors

In addition to the causes for the sinking of the Pamir , the main question was why so few crew members survived despite the quick start of the intensive rescue operation. Above all, the short-term and little planned leaving of the sinking Pamir was criticized.

The lifeboats

The lifeboats were apparently a big problem: only relatively shortly before the Pamir sank, attempts were made to lower the boats into the water. At this time, however, the lifeboats on the port side were already under water due to the strong list, while the boats on the starboard side could no longer be lowered into the water due to the high lean angle. The crew only had three lifeboats that had torn loose before or when capsizing and were badly damaged; in addition, they did not float in the immediate vicinity of the ship in the stormy seas.

The Pamir was also equipped with three inflatable life rafts, two of which could not be found on board before the sinking. According to contradicting information, the third life raft was initially used by several crew members; when they later saw one of the three lifeboats, they gave up the life raft and swam to the boat. In other information, based on an interview with the survivor Karl-Otto Dummer , the life raft is not mentioned in this context: According to Dummer, around 20 castaways clung to floating wreckage; ten of them managed to get to the floating lifeboat. There does not appear to be any further information from survivors that the life raft was used by other castaways.

The survivor Karl-Otto Dummer stated that "probably many [of the crew members] had drowned" when the Pamir capsized and the sailors fell from deck into the water. According to other reports, several crew members are said to have stayed in the ship or got under the ship when it capsized. About five sailors climbed onto the Pamir's hull after capsizing , presumably believing that the ship could not sink. Other sailors got entangled in the cordage and were pulled below the surface of the water by the Pamir .

The severe damage to the three available lifeboats reduced the chances of survival of the men who reached the boats in several ways. The lifeboats were largely filled with water due to the damage and were therefore very deep in the water; they only swam because of the few undestroyed air tanks. Survivor Dummer said the water was up to their chests in lifeboat No. 5; the survivor of boat no. 2 waited on the railing of the flooded boat. On the one hand, the low position of the boats meant that some of the men drowned in the boats (at least two men in boat no. 5). On the other hand, the low-lying boats with the upper bodies of the shipwrecked people barely protruding above the surface of the water could hardly be seen in the still "raging sea": Several ships passed the boats within sight without discovering them. The men on lifeboat number 5 finally built a mast in their boat on the morning of September 23 to improve their chances of being rescued.

To make matters worse, the sea rescue equipment (flares) had become wet and unusable or had been lost due to the damage to the lifeboats . As a result, the survivors in the boats later had no way of attracting the attention of passing search ships and aircraft. This made a search success practically impossible, especially at night. In addition, there was the inconspicuous color of the boats: the wooden hulls were, as was common at the time, not painted in color and therefore very difficult to spot even during the day at short distances; Those involved in the search later stated that the significantly smaller but colored life jackets were seen from a much greater distance.

Another problem was that the supplies stored in the boats, including the drinking water supplies, had largely been lost. According to survivor Dummer, the ten crew members who were initially able to save themselves in lifeboat No. 5 had only "a few cans of canned milk" at their disposal. Another representation does not speak of canned milk, but of a fresh water barrel found in the boat and at least one bottle of schnapps brought along; However, both were lost when the damaged boat capsized once in the stormy sea. In any case, thirst is unanimously portrayed as one of the greatest problems of the castaways. Two of the ten men in lifeboat No. 5 eventually drank salt water and left the boat hallucinating ; another swam away just two hours before the rescue ship Saxon arrived and could not be found. Similar scenes are said to have taken place in lifeboat No. 2, in which 20 to 22 people had initially found protection and, according to the statements of the only survivor of them (Günther Haselbach), ten people were still alive 24 hours before the rescuers arrived.

Other causes

According to some commentators, this situation was exacerbated by the lack of food and, above all, drinking on the Pamir just before the sinking. Among other things, just before the capsize, only cigarettes and several bottles of schnapps were handed out instead of lunch. A fancy meal on a tall ship sailing through a storm was not uncommon. However, it was pointed out that, for example, the crew members of General Belgrano , sunk with a torpedo in the Falklands War , who also endured two or three days without food and practically without water, were very well nourished right before the sinking.

In addition , there was speculation about the mental condition, mainly due to the age of the Pamir crew. 51 of the 86 crew members were cadets in training and a total of 45 of the crew members were under 18 years of age. In addition, the departure of the Pamir was not arranged in an organized manner by the master. It is therefore assumed that some of the survivors for the time being gave up their lives in this extreme situation more quickly than a professional ship crew with better mental preparation.

In retrospect, it is difficult to assess what part sharks played in the fate of the shipwrecked. In the area in which the Pamir sank, there were, according to consistent information, many sharks, and the Lübeck Maritime Office also made connections to the "traces of human bodies" that were found on September 25 with life jackets tied together. Sharks may also kill some of the lifeboat occupants as they swam away from the boats. Nevertheless, one can obviously only speculate whether or how many castaways died from sharks and how many had already drowned or died of hypothermia. It can be assumed that some crew members drowned in the hurricane. In close proximity to the surface of the water (head of a swimming person), the spray alone in the middle of a heavy storm can lead to the inhalation of so many small water particles that they cannot be broken down by the lungs fast enough and can cause drowning after about an hour.

In this context it can also be seen that some seafarers were rescued who, despite wearing a life jacket, floated face down in the water. Unlike modern "faint-proof" life jackets , which even keep a sleeping or unconscious person afloat in the supine position with their face above water, the vests of that time could not have adequately protected crew members from drowning. However, this problem apparently existed in general with the life jacket models that were common at the time, and not only with those on the Pamir . In view of the repeatedly emphasized risk of sharks, it is generally unclear whether the information about the corpses recovered in the prone position is really true. But even then, for the reasons mentioned above, it would not be certain whether the seamen actually drowned because of the life jackets.

Summary

Overall, it is therefore assumed that the high number of victims of the Pamir doom was largely caused by the late and poorly prepared departure from the ship or the lack of sufficient and well-equipped lifeboats and life rafts. To what extent the capsizing of the Pamir was foreseeable in time for the captain and officers at all is difficult to judge because of the disputed cause of the sinking. Last but not least, the number of casualties must also be seen against the fact that the Pamir sank in the face of a strong hurricane - the strongest of 1957 - and in an area where there were many sharks.

Consequences of doom

The sinking of the Pamir meant that only a few weeks later the other German sailing training ship, the Passat , was also taken out of service. A few days after the sinking of the Pamir , the Passat , also laden with barley, barely escaped a hurricane near the Azores . Existing intentions to put further ships - in particular the Moshulu (ex Kurt ) and the Flying P-Liner Pommern - back into service as additional freight-carrying sailing training ships were dropped without replacement. After the Pamir left for its last voyage - before it went down - ten of the 41 member shipping companies in the “Pamir and Passat Foundation” terminated their membership in due time. This ended the era of large sailing training ships with cargo around the world.

As early as 1952 there was no longer any obligation for budding navigators in merchant shipping to spend time on sailing ships. On the other hand, from 1952 it became a requirement for future boaters in the deck career to attend a two-month training course at one of the six seaman's schools (Hamburg-Falkenstein, Finkenwerder and Bremervörde; Travemünde Priwall ; Bremen Schulschiff Deutschland and Elsfleth), and from 1956 a three-month training course. In 1963, the insurance compensation from the Pamir , which could only be used for a new training ship, flowed together with other funds into the acquisition of the much smaller gaff - Ketsch Seute Deern (two-master, not to be confused with the museum ship Seute Deern in Bremerhaven). Due to the experiences from the sinking of the Pamir and a near miss of the Passat , special emphasis was placed on the stability of the ship when selecting the Seute Deern and during extensive renovations prior to its first use. H. on its ability not to overturn: the ship's ballast was laid out very generously so that it did not heel even in strong winds. The Seute Deern was used for training trips for almost three years. In contrast to the times of the Pamir , however, no more freight was transported, and the journeys were only a few weeks long and only led to the North and Baltic Seas. To this day, the Jade University offers the opportunity to serve time on a club-owned school ship. The Grand Duchess Elisabeth is the last sailing training ship on which future officers of the German merchant navy can be trained.

Due to the sinking of the Pamir , the plans for the construction of the already approved sailing training ship Gorch Fock (launched in 1958) of the German Navy were changed again and further safety precautions were taken.

In Belgium, plans to build a new barque as a sailing training ship had also already been approved and the financing secured. However, the project was completely abandoned after the results of the investigation by the Lübeck Sea Office became known.

Memorial sites and whereabouts of the rescued lifeboats

In the Jakobikirche in Lübeck , the former Witte chapel was redesigned as the Pamir chapel : It houses the Pamir lifeboat no.2 , which was leaked and from which a survivor was rescued, as well as information about the accident, including notes from one survivor. The chapel also commemorates the loss of other Lübeck ships and their crews. On the walls of the chapel hang wreaths and ribbons from German and foreign seamen and delegations who visited the chapel. On September 21, 2007, the chapel was declared a National Memorial to Civilian Seafaring.

In Hamburg's Katharinenkirche a memorial commemorates the sinking of the Pamir . The remains of lifeboat No. 6 of the Pamir are exhibited in the extension of the German Maritime Museum in Bremerhaven . A piece of the side of the lifeboat No. 5, on which five crew members survived, can be seen in the Maritime Museum in Brake . The remaining whereabouts of the lifeboat are said to be unclear , according to the Hamburger Abendblatt, and the survivor Dummer is suspected of being in Minneapolis (USA).

On Eternal Sunday of each year, the St. Pauli fish market is held at a memorial ceremony for the seafarers who have died and gone missing at sea. Wreaths and flowers are laid at the monument to the Madonna of the Seas .

Filming the downfall

As early as 1959, Heinrich Klemme made a documentary about the Pamir and its sinking using older film material (see films ).

In the summer and autumn of 2005, the television film The Downfall of the Pamirs was shot. After the premiere on October 8, 2006 at the Hamburg Film Festival , the film was shown on German television for the first time in November 2006. According to the survivor Dummer, the screenwriter Fritz Müller-Scherz deviated greatly from the facts for the film.

"Sisters" of the Pamirs

See detailed description in the article Passat (Schiff, 1911) in the section " The Eight Sisters "

The Pamir was one of the last eight four-masted barques built for the F. Laeisz shipping company, which were launched from 1903 ( Pangani ) to 1926 ( Padua ). Because of their similarity, these eight ships were called “The Eight Sisters” or, misleadingly, “The Eight Sister Ships” . Of the eight ships, however, only the Passat and the Peking as well as the Pola and the Priwall were sister ships in the narrower sense (i.e. with the same construction plans) . The two pairs of ships were each built according to almost identical plans in a short period of time. The Pamir , a few years older , was built similarly, but had no sister ships in the strict sense. In terms of gross tons and length, she was the smallest of the eight sailors, but was considered the most robust of them.

The frequent classification of the Passat as the Pamir's sister ship could, in addition to their structural similarity, also be due to the fact that the two ships belonged to the same owners for most of the time until the Pamir's sinking . Above all, the use of both ships in the 1950s as the last two large sailing training ships in German merchant shipping should have contributed to the assessment. For example, even former crew members are reported to have spoken of the two ships as sister ships.

All records of the Pamirs

According to "internal documents of our shipping company" (Laeisz):

- 1905 English Channel - Valparaiso 70 days

- 1925 Ushant - Talcahuano 71 days

- 1926 Iquique - Prawle Point 86 days

- 1928 Talcahuano - Ipswich 83 days

- 1928/9 Iquique - Prawle Point 86 days

- 1929 Iquique - Bruges 87 days

- 1930 Rotterdam - Talcahuano 90 days

- 1930 Iquique - Ghent 85 days

- 1930/1 Lizard - Corral 79 days

- 1931 Iquique - Bordeaux 108 days

- 1932 Wallaroo - Queenstown 103 days

- 1933 Australia - England 92 days (including 4 days of calm and fog at the Isles of Scilly )

See also

- Captains and crew of the Pamir

- Brotherhood of Cape Horniers

- All journeys of the Pamirs

Movies

- Bill Colleran, Louis De Rochemont III: Windjammer (1957)

- Heinrich Hauser : The Last Sailing Ships (1930)

- Kaspar Heidelbach: The Downfall of the Pamir (2006), 178 minutes, produced as a two-part TV series.

- Karsten Wohlrab, Andreas Vennewald: The Pamir - sinking of a tall ship. Documentary by NDR (2006)

- Heinrich Klemme : The Pamirs (1959). Using footage by W. P. Bloch (1952) and Heinrich Hauser (1930). 88 minutes. ISBN 3-9807235-9-3 (meanwhile also as DVD, black and white and color scenes)

literature

- Rudolf Andersch: The white wings. Life and death of the ship Pamir . Schlichtenmayer publishing house, Tübingen 1958.

- Erich R. Andersen: Pamir and Passat - the last German commercial sailors. Pro Business Verlag, Berlin 2007, ISBN 978-3-939533-53-5 .

- Jochen Brennecke , Karl-Otto Dummer : The four-masted barque Pamir - her fate in the center of the hurricane "Carrie" . Koehlers VG, Herford 1986, ISBN 3-548-23531-X .

- Jochen Brennecke, Karl-Otto Dummer: Pamir - a fate . Koehlers VG, Herford 1977, ISBN 3-7822-0141-8 .

- Heinz Burmester: With the Pamir around Cape Horn . Gerhard Stalling, Hamburg 1974.

- Karl-Otto Dummer, Holger Husemann: four-masted barque Pamir. The story of a legendary P-Liner. Portrayed by a survivor of doom. Ed .: German Maritime Museum . Convent, Hamburg 2001, ISBN 3-934613-17-9 (illustrated non-fiction book. Dummer has published his books on the basis of his small private, worldwide researched text and image archive on the Pamir)

- Heinrich Hauser : The last sailing ships. One hundred and ten days on the “Pamir” . Koehlers VG, Herford 1958, ISBN 3-7822-0123-X .

- Jens Jensen : The fate of the Pamirs. Biography of a windjammer . Europa-Verlag, Hamburg / Vienna 2002, ISBN 3-203-75104-6 . (Documentary representation of the ship's history in the form of a novel)

- Klaus Reinhardt: The sinking of the Pamir. The last chapter in the history of a German sailing ship. The hearing in front of the Lübeck Maritime Office. Published in the "Kieler Nachrichten" from 7 to 21 January 1958. Kieler Nachrichten, Kiel 1958.

- Seeamt Lübeck (ed.): The sinking of the sailing training ship "Pamir" . Report. Hamecher Verlag, Kassel 1973, ISBN 3-920307-13-5 . (NEW: Book-on-Demand , Bremen 2011, ISBN 978-3-8457-0028-1 )

- Johannes K. Soyener: Storm legend. The last voyage of the Pamirs. Lübbe, Bergisch Gladbach 2007, ISBN 978-3-7857-2287-9 . (According to its own information "Tatsachen-Roman", which critically processes the original documents of the shipping company about the ship's command and condition) Website for the book

- William F. Stark: The last time around the horn. The end of a legend, told by someone who was there. Piper, Munich 2003, ISBN 3-492-24085-2 . (Stark was a crew member of the Pamir during the last part of the wheat regatta and the last voyage around Cape Horn)

- Eigel Wiese: Pamir - the splendor and sinking of a sailing ship. 2nd Edition. Koehler Verlag, Hamburg 2007, ISBN 978-3-7822-0964-9 .

- Horst Willner: Pamir. Their downfall and the mistakes of the Maritime Administration. Mittler & Sohn, Herford / Bonn 1991, ISBN 3-7822-0713-0 . (Perspective of the lawyer who represented the shipping company after the sinking of the Pamir )

- Armin Peter (Pitt): The Pamir, the captain and the cadet. Novel. Norderstedt 2017, ISBN 978-3-7448-2675-4 . (From the perspective of the bereaved; the author's wife has lost her brother there)

- Further literature in German and English is available, for example, on the website of the Finnish Kaphoorniers

Web links

- Very extensive website on the Pamir ( French and - in some cases automatic - translations into German and English )

- The Pamir set course for Australia - travel pictures: November 1931 to August 1932

- Information on the radio equipment of the Pamir as well as on the radio messages before her sinking. seefunknetz.de

- September 21, 1957: Sail training ship Pamir sinks . Deutsche Welle : Program from the "DW Calendar Sheet" series (September 21, 2005)

- Why did the Pamirs sink? ( Memento from August 20, 2009 in the Internet Archive ) In: Kölner Stadtanzeiger . September 24, 1977.

- Brief overview of the history of the Pamirs with their travel times for various long-distance routes. esys.org

- Press kit St. Jakobi zu Lübeck - National Pamir Chapel Memorial ( Memento from September 29, 2007 in the Internet Archive ) (PDF), February 2006

- Reprints of previously unpublished documents from the files of the "Pamir and Passat" foundation from the Bremen State Archives on financial problems, management problems and the condition of the ship (together with advertising for a novel and the author's non- neutral comments)

- "Pamir" sinks in a hurricane . In: Die Welt , November 19, 1999.

- Chapter seafaring : Large obituary for the sixth survivor Günter Haselbach.

- Pamir, 1914-21 as reflected in the contemporary press

Footnotes

- ↑ According to information from pamir.chez-alice.fr, however, 3,800 m² (34 cotton sails ) and a maximum sail area of 4,000 m² (with all staysails ) (accessed May 1, 2020)

- ↑ a b Fall of the Pamir, Three Questions . In: Der Spiegel . No. 30 , 1958 ( online ).

- ↑ Uwe Bahnsen, Kerstin von Stürmer: Trümmer / Träume / Tor zur Welt The history of Hamburg from 1945 to today. Sutton Verlag, Erfurt 2012, ISBN 978-3-95400-050-0 , p. 94.

- ↑ The "Pamir" (on "gorchfock.de"). Retrieved April 27, 2020 .

- ↑ Launched. Retrieved April 12, 2018 .

- ↑ Walter Kozian: The four-masted barque "Pangani". (PDF) p. 8/38 , accessed on February 15, 2018 .

- ^ Pamir 1905. Retrieved February 17, 2018 .

- ↑ European sailing information system: Tall ship: The "Pamir". Retrieved May 1, 2020 .

- ↑ Pamir (1 (part). In: Escobén. December 9, 2005, accessed May 1, 2020 .

- ↑ Ursula Feldkamp: An insatiable longing. (PDF) p. 1/6 , accessed on January 14, 2018 (1910 Captain: Becker or Horn ???).

- ↑ Captain Hans Blöss: Citizens of the oceans and seas. Retrieved January 14, 2018 .

- ↑ Hamburg – Valparaiso – Valley. Retrieved February 1, 2018 .

- ^ Börsen-Halle / from 1905: Hamburg Correspondent and new Hamburg Stock Exchange Hall . March 2, 1914, p. 3 .

- ^ Börsen-Halle / from 1905: Hamburg Correspondent and new Hamburg Stock Exchange Hall . July 24, 1914, p. 44 .

- ^ Taltal 1913. Retrieved January 13, 2018 .

- ↑ first details. Retrieved March 16, 2018 .

- ↑ a b Heinz Burmester: The four-masted barque Pamir, a cargo sailor of the 20th century. (PDF) p. 74 , accessed on January 8, 2018 .

- ↑ El Progreso: diario republicano (Año IX - Número 2766) . October 9, 1914.

- ↑ Original receipt for the previous one. Retrieved May 1, 2020 .

- ↑ Picture of Macedonia in Wikimedia Commons.

- ↑ El Progreso: diario republicano (Año IX - Número 2805) . November 25, 1914.

- ↑ Original receipt for the previous one. Retrieved May 1, 2020 .

- ^ Tyne Built Ships; Savannah = Sommelsdijk II. Retrieved January 8, 2018 (The top of the two pictures shows the Sommelsdijk I , which burned down in the port of Rotterdam in 1910. The bottom picture shows the Sommelsdijk II in war paint).

- ^ Team list, page 99. Retrieved on May 14, 2018 .

- ↑ Captain Jürgen Jürs: From Elmshorn around Cape Horn. City of Elmshorn, accessed on January 6, 2018 .

- ↑ Pamir and Roads from S / C Palma. Retrieved January 13, 2018 .

- ↑ macedonia1. Retrieved July 18, 2018 .

- ^ Original reference to: El Progreso: diario republicano: Año IX Número 2805 - 1914 noviembre 25. Retrieved on January 9, 2018 .

- ^ El bien público: Epoca Segunda (Año XLII - Número 12468) . November 24, 1914.

- ↑ Original receipt for the previous one. Retrieved May 1, 2020 .

- ↑ Original document on: El Cantábrico: diario de la mañana (Año XXI - Número 7921). March 19, 1915, accessed May 1, 2020 .

- ↑ Macedonia 2. Retrieved July 21, 2018 .

- ↑ Juan Antonio Padrón Albornoz: La isla y los Barcos. El Día magazine , March 6, 1970, accessed January 15, 2018 (Spanish).

- ↑ Special / official. In: www.rottbank.org. Retrieved January 16, 2018 .

- ^ "Enemy vessel" by Lloyd's Register. Retrieved January 9, 2018 .

- ↑ 26-08-1918. Retrieved September 24, 2018 .

- ↑ Dieter Merges: "Pamir" 1914-21, valley - Santa Cruz de La Palma - Hamburg. January 23, 2018, accessed January 23, 2018 .

- ↑ "Pamir". Retrieved on February 9, 2018 (poem by José Miguel Pérez, published March 1917, text in Spanish, also translated into German).

- ↑ Museo Naval S / C de La Palma. Retrieved May 1, 2020 .

- ↑ La prensa: diario republicano: Año VIII Número 2499 - March 7, 1918 - page 2. Accessed May 1, 2020 .

- ↑ memorial plaque. Retrieved May 1, 2020 .

- ↑ Laeisz, June 1917. Retrieved July 19, 2018 .

- ↑ according to Hamburger Anzeiger , April 12, 1920, p. 3, even only the captain, 3 helmsmen, the carpenter and 3 sailors. (http://www.theeuropeanlibrary.org/tel4/newspapers/issue/Hamburger Anzeiger / 1920/4/12)

- ^ Rol-salida. Retrieved September 21, 2018 .

- ↑ Jaime Pérez García: Casas y familias de una ciudad histórica: la Calle Real de Santa Cruz de La Palma . Ed .: Cabildo Insular de La Palma y Colegio de Arquitectos de Canarias. ISBN 84-87664-07-5 (see pages 28–34, footnote 78: Edificio “Mayantigo”, Calle O'Daly 37 (2018)).

- ↑ La Prensa: diario republicano (Año X - Número 3211) . March 7, 1920.

- ↑ Original receipt for the previous one. Retrieved May 1, 2020 .

- ↑ Team list, page 110. Retrieved on August 16, 2018 .

- ↑ Juan Carlos Díaz Lorenzo: velero alemán Pamir en S / C de la Palma. Retrieved January 8, 2018 (Spanish).

- ↑ El Progreso: diario republicano: Año XV Número 4484 - March 11, 1920 - p. 2 . (to be found on page 2 in the section Vida marítima on https://prensahistorica.mcu.es/es/publicaciones/numeros_por_mes.cmd?idPublicacion=7295&anyo=1920 ).

- ↑ Juan Carlos Díaz Lorenzo: La Palma, en la ruta de los veleros . (see page 39 f: when the “Jorge V” arrives at the same time).

- ↑ La Gaceta de Tenerife: diario católico de información: Año X Número 3025 - 1920 March 11. Accessed on January 11, 2018 (Spanish, under “Notas marítimas” as evidence of the previous).

- ↑ Hamburg as a port city (at that time). (No longer available online.) Archived from the original on January 17, 2018 ; accessed on January 16, 2018 . Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice.

- ↑ according to the report in Börsen-Halle / from 1905: Hamburgischer Correspondent and neue Hamburgische Börsen-Halle, October 22, 1920, p. 13 theeuropeanlibrary.org

- ↑ “There is an accident here for which the ship's command bears no responsibility.” In: Börsen-Halle / from 1905: Hamburgischer Correspondent and new Hamburgische Börsen-Halle, April 23, 1920, p. 3 theeuropeanlibrary.org

- ↑ Jürs, Priwall, La Palma. Retrieved May 1, 2020 (in: El Progreso, diario republicano - Año XV Número 4626 - August 26, 1920 - p. 1).

- ↑ according to Hamburger Anzeiger of June 1, 1921, p. 4 ( http://www.theeuropeanlibrary.org/tel4/newspapers/issue/Hamburger%20Anzeiger/1921/6/1?page=4 )

- ^ Hamburg-Castellammare. Retrieved May 1, 2020 .

- ^ Castellammare at that time. (No longer available online.) Archived from the original on February 15, 2018 ; accessed on August 31, 2018 .

- ↑ Jürgen Prommersberger: Windjammer: The last bloom of the great cargo sailors 1880-1930 . (At Prommersberger, the Pamir arrives (incorrectly) in Hamburg on March 17th. Burmester in dsm.museum (PDF) is correct here with “after 31 days of travel on April 10th, 1921”, but then continues with “The Italians who die Pamir was assigned, they took over this date in the port of Hamburg in March 1921 "before the arrival time he himself stated. Burmester continues:" The Italian flag was hoisted and the home port Roma was painted on the stern. In the summer, Captain Ambrogi brought the ship with him a load of coal from Rotterdam to Naples, then it was launched. ”Prommersberger sets the start of the Italians in tow on July 15, 1921.).

- ↑ Noah Adomat: Giants of the Seas - The largest and most imposing ships on earth .

- ↑ as of June 2020: Discussion: Pamir (ship) # 15. July 1921: Hamburg - Castellammare di Stabia, under Captain Ambrogi?

- ↑ Börsen-Halle, November 17, 1923. Retrieved May 20, 2018 .

- ↑ Hamburger Anzeiger, 19-11-1923. Retrieved May 20, 2018 .

- ^ Hans Georg Prager: Shipping company F. Laeisz . Koehlers Verlagsgesellschaft, Hamburg 2004, ISBN 3-7822-0880-3 .

- ↑ "enemy vessel". Retrieved April 28, 2018 .

- ↑ Börsen-Halle, 27-03-1924. Retrieved May 1, 2020 .

- ↑ Börsen-Halle, 12-05-1924. Retrieved May 1, 2020 .

- ↑ Hamburg State Archives 111-1. (PDF) Retrieved on May 13, 2018 (Findbuch, Volume 7, under No. 13097).

- ^ Börsen-Halle / from 1905: Hamburg Correspondent and new Hamburg Stock Exchange Hall. Hamburg State Library, p. 18 , accessed on May 1, 2020 .

- ↑ Hamburger Anzeiger. July 28, 1931, p. 6 , accessed May 1, 2020 .

- ^ Michael Friedewald: Telefunken and the German ship radio 1903-1914. (PDF) Accessed August 31, 2018 .

- ↑ a b Jens Jensen: The fate of the Pamir. Europa-Verlag, Hamburg 2002.

- ↑ Australia: Pictures from November 1931 to August 1932. Retrieved November 28, 2018 .

- ↑ Jens Jensen: The fate of the Pamir. Europa-Verlag, Hamburg 2002, pp. 128–129.

- ↑ a b c d Daniel S. Parrott: Tall Ships Down. The Last Voyages of the Pamir, Albatross, Marques, Pride of Baltimore, and Maria Asumpta. International Marine / McGraw-Hill, Camden ME 2003, p. 28.

-

↑ Churchouse (1978) quoted for the course of events from the notes of the Third Officer Francis Renners, only the position information comes from the logbook of the Pamir kept by Captain Champion . Churchouse commented on the uncertainties and causes.

Jack Churchouse: The "Pamir" under the New Zealand Ensign . Millwood Press, Wellington / New Zealand 1978, ISBN 0-908582-04-8 , p. 115. - ↑ Klaus J. Hennig: Death in a hurricane. The sinking of the mighty school sailor “Pamir” in 1957 will not be forgotten. Many puzzles surround the greatest shipwreck in German post-war history - now television has filmed the maritime tragedy . In: Die Zeit , No. 47/2006, series of time runs ; there, however, the submarine "A-12" is incorrectly mentioned, as is the article in the Kölner Stadtanzeiger (September 24, 1977). Why did the Pamirs sink? ( Memento of August 20, 2009 in the Internet Archive ) (accessed November 15, 2006). However, there was no submarine "A-12" in the Japanese Navy, Corvette Captain Kudo Kaneo actually commanded I-12 . (see also the following footnote)

- ↑ HIJMS Submarine I-12: Tabular Record of Movement ( engl. ) (Accessed December 1, 2006)

- ^ The Illustrated London News. April 3, 1948, Retrieved October 15, 2018 .

- ^ William F. Stark: The last time about the horn. P. 100 , accessed March 10, 2018 .

- ^ William F. Stark: The last time about the horn . Ed .: marebuch. 3. Edition. Piper Verlag GmbH, Munich 2007, ISBN 978-3-492-24085-7 , p. 167 .

- ↑ Rank Mills / Barry Docks. Retrieved March 10, 2018 .

- ↑ Remembering the Passat and Pamir. Retrieved May 1, 2020 .

- ^ Rat Ship. Retrieved March 9, 2018 .

- ↑ Annual Report 1950 . Barry Port Health Authority, Text Archive - Internet Archive

- ↑ Penarth Dock. Retrieved March 10, 2018 .

- ^ The end of an era. (PDF) Retrieved March 10, 2018 .

- ^ The Van Loo company at work in Vierville. Retrieved March 9, 2018 (see also: http://omaha-vierville.com/Webvierville/574-Epaves.htm ).

- ↑ Seeamt Lübeck: The sinking of the sailing training ship "Pamir". Retrieved March 9, 2018 .

- ↑ Seeamt Lübeck: The sinking of the sailing training ship "Pamir" Pages = 11 .

- ↑ “Pamir” - a 60 años de su naufragio. Retrieved April 29, 2018 .

- ↑ a b Interview with the cabin boy Klaus Arlt. Klaus Arlt - A cabin boy remembers. ( Memento from August 22, 2012 in the Internet Archive ) In: perfect4all. (accessed November 15, 2006)

- ^ Daniel S. Parrott: Tall Ships Down. The Last Voyages of the Pamir, Albatross, Marques, Pride of Baltimore, and Maria Asumpta. International Marine / McGraw-Hill, Camden ME 2003, p. 32.

- ↑ Juan Antonio Padrón Albornoz: La isla y los barcos , in: El Día , March 6, 1970 . S. 4 (with photo).

- ^ Rol-entrada. Retrieved September 21, 2018 .

- ↑ Diebitsch, Xarifa, Tenerife. Retrieved on January 25, 2018 (when asked about his stay with the Pamir in La Palma between 1914 and 1920 during this visit, he explained his disappearance at the beginning of March 1918 as follows: Together with another member of the team (according to Mario Suárez Rosa in elapuron.com : Carl Schuberg - who in turn, according to Kruzenshtern (ship) #Passagen und Kapitäne , was captain of the Padua in 1926) he took the little sailor I'll try from the English Vice Consul in Santa Cruz de La Palma and brought it to Cádiz, where they were finally arrested (published in: Diario de Avisos, October 24, 1953, p. 3) Although he still assures that there was some turbulence at the time and that 15 pounds sterling was also given for pertinent information on the whereabouts of the boat no trace of this has yet been found in the contemporary press.)

- ↑ a b c d e Klaus J. Hennig: Death in the hurricane. The sinking of the mighty school sailor “Pamir” in 1957 will not be forgotten. Many puzzles surround the greatest shipwreck in German post-war history - now television has filmed the maritime tragedy . In: The time . No. 47/2006, series time runs

- ↑ u. a. Photo departure from Buenos Aires. Retrieved October 15, 2018 .

- ↑ a b Map with the route of the Pamir and the railway of "Carrie". pamir.chez-alice.fr

- ↑ According to the information on seefunknetz.de , accessed on November 17, 2006. In contrast, according to the manuscript of the broadcast by Annette Riedel ( "SOS from PAMIR. Captain." A survivor reported. In: Deutschlandradio Kultur, Country Report , November 1, 2006 , accessed on November 15, 2006) the second SOS call was made at 11:02 a.m.

- ↑ So the description in Segeln (magazine) (03, 2000), which is also incorrect in other points : The sinking of the Pamir ( Memento of March 22, 2009 in the Internet Archive ) (accessed November 15, 2006)

- ↑ a b c d e f g h Why did the Pamirs sink? ( Memento from August 20, 2009 in the Internet Archive ) In: Kölner Stadtanzeiger. September 24, 1977; Retrieved November 15, 2006.

- ↑ a b H. Busch on seefunknetz.de , accessed November 17, 2006, with the source "Karlheinz Müller and HG Korth"

- ↑ Different time indications are likely to be due to the fact that the time indications are partly given in a different time zone (especially Greenwich Mean Time ) and the incomprehensible radio signal is not always counted. This is what it says with Silke Bartlick (September 21, 2005). September 21, 1957: Sail training ship “Pamir” sinks , Deutsche Welle (accessed November 15, 2006) , the last radio message was made at 2:57 pm. This is the time after Greenwich Mean Time at which the Pamirs sent their last intelligible radio signal. Corresponding differences also arise for the other time specifications, e.g. B. the time when the Pamir capsized

- ^ Report of the Lübeck maritime office: The sinking of the sailing training ship "Pamir". Hamecher Verlag, Kassel 1973.

- ↑ So z. B. in the Kölner Stadtanzeiger (September 24, 1977). Why did the Pamirs sink? ( Memento of August 20, 2009 in the Internet Archive ) (accessed November 15, 2006) and in Annette Riedel (November 1, 2006). "SOS from PAMIR. Captain. ”One survivor reports. Deutschlandradio Kultur, country report (accessed April 27, 2020); on the other hand, at http://www.seefunknetz.de/dkef.htm (accessed November 17, 2006) only 60 ships are mentioned.

- ↑ So z. B. http://www.seefunknetz.de/dkef.htm (accessed November 17, 2006) and Annette Riedel (November 1, 2006). "SOS from PAMIR. Captain. ”One survivor reports. Deutschlandradio Kultur, country report (accessed April 27, 2020); however, it is in the Kölner Stadtanzeiger (September 24, 1977). Why did the Pamirs sink? ( Memento of August 20, 2009 in the Internet Archive ) (accessed November 15, 2006) talked about 15 ships.

- ^ Armando Uribe: Memorias para Cecilia . Penguin Random House Grupo Editorial Chile, 21 recién casados (Spanish).

- ↑ Fritz Müller-Scherz: The sinking of the Pamir. Afterword by the author . ( Memento of September 26, 2007 in the Internet Archive ) Internet site of the screenwriter of The Fall of the Pamirs ; Retrieved November 20, 2006.

- ↑ "jozi": A nation trembles with . ( Memento of September 27, 2007 in the Internet Archive ) In: Aachener Zeitung , September 23, 1997; Retrieved November 24, 2006.

- ↑ Uwe Bahnsen, Kerstin von Stürmer: Trümmer / Träume / Tor zur Welt The history of Hamburg from 1945 to today. Sutton Verlag, Erfurt 2012, ISBN 978-3-95400-050-0 , p. 93.

- ↑ a b Annette Riedel (November 1, 2006). "SOS from PAMIR. Captain. ”One survivor reports. Deutschlandradio Kultur, country report (accessed April 27, 2020)

- ↑ Captain Hans-Bernd Schwab (1999). Reflections on the sinking of the Pamir on September 21, 1957. New considerations on the marine casualty in connection with the use of sailing ships for bulk transports. ( Memento of October 9, 2007 in the Internet Archive ) (accessed November 26, 2006)

- ^ Daniel S. Parrott: Tall Ships Down. The Last Voyages of the Pamir, Albatross, Marques, Pride of Baltimore, and Maria Asumpta. International Marine / McGraw-Hill, Camden ME 2003, pp. 45 and 51

- ↑ according to Horst Willner's description of a very similar photo - but with dramatic elevation of waves and sky. - Horst Willner: Pamir. their downfall and the errors of the Maritime Administration. ES Mittler & Sohn. Herford / Bonn 1991, p. 65.

- ↑ Horst Willner: Pamir: Your downfall and the errors of the sea office . ES Mittler & Sohn, Herford / Bonn 1991, ISBN 3-7822-0713-0 .

- ↑ So at least a letter to the editor on a comment about Willner's lack of neutrality on gerdgruendler.de ( Memento from June 16, 2007 in the Internet Archive ).

- ↑ gerdgruendler.de ( Memento from August 20, 2009 in the Internet Archive ) (accessed November 15, 2006)

- ^ Daniel S. Parrott: Tall Ships Down. The Last Voyages of the Pamir, Albatross, Marques, Pride of Baltimore, and Maria Asumpta. International Marine / McGraw-Hill, Camden ME 2003, p. 40.

- ^ Daniel S. Parrott: Tall Ships Down. The Last Voyages of the Pamir, Albatross, Marques, Pride of Baltimore, and Maria Asumpta. International Marine / McGraw-Hill, Camden ME 2003, pp. 40-41.

- ↑ a b c d e So Nicolás Yaksic Triantafilo (Second Lieutenant Naval Reserve). The Lost Wake of the "Pamir". Chilean Navy Review No. 2/95 ( Memento of April 28, 2004 in the Internet Archive ) (English), printed on the website of the Chilean Cape Horniers (accessed November 20, 2006).