Crown Prince Wilhelm (ship, 1901)

|

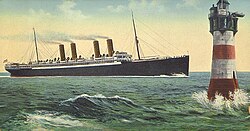

The Crown Prince Wilhelm at the Roter Sand lighthouse

|

||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||

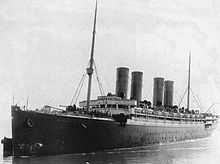

The Crown Prince Wilhelm was a German passenger ship of the North German Lloyd (NDL) completed in 1901 for liner shipping on the Transatlantic Passage Bremerhaven – New York. With its four funnels, it embodied the twin-screw express mail steamer, the most popular and spectacular type of ship at the time, combining the latest technical developments with speed and luxury. In 1902, Crown Prince Wilhelm won the Blue Ribbon and was on the line until 1914. After the outbreak of World War I , he waged a successful trade war as an auxiliary cruiser in the North Atlantic for eight months, was later confiscated by the Americans and used as an Allied troop transport on the New York – Brest line.

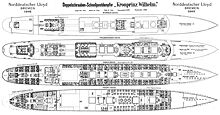

Ship equipment

The express steamer with its abundant equipment and exquisite food was an enlarged and improved version of the Kaiser Wilhelm the Great . For example, a few hundred more horsepower were extracted from the engine system of the Crown Prince Wilhelm , which was similar in both ships , which led to an unprecedented engine output of 33,000 hp (24,000 kW ). Coal bunkers with a capacity of around 4,550 tons of coal were arranged around the four groups of steam boilers . Two six-cylinder quadruple expansion steam engines with surface condensers and mass balancing according to the Schlick system drove a four-wing bronze screw each over two 42-meter-long and 0.63-meter-thick shafts made of crucible steel . The steam pressure was supplied by 12 double and four single boilers which operated at 15 atmospheres overpressure.

The ship had a direct current system and was heated by an electric heating device, which gave its energy to a total of 104 electric ovens. These ovens were installed in the first class outside cabins, on the promenade deck and in the first class dining room. Everywhere on board there was electric light from over 1900 lamps fed by four steam dynamo machines. Each of these dynamos was 825 amps at 100 volts . Since two dynamo machines were already securing the energy supply for the entire electrical system on board, the other two machines were on standby for emergencies. Around 60 electric motors of various sizes were provided to operate overhead cranes, fans, elevators, cooling systems and auxiliary machines. With the help of six steam winches, provisions, luggage and cargo were taken over. The shipping company placed particular emphasis on the technical safety equipment. An electric bulkhead telegraph located in the card room was able to close the twenty existing watertight doors simultaneously in an emergency. The closing of a bulkhead door was indicated on the telegraph by the lighting of a light bulb. 3.2 kilometers of special cable and 1.2 kilometers of simple cable were installed only for the technical installation of the bulkhead function. The ship had 18 wooden lifeboats with air boxes and six half-folding boats made of galvanized sheet steel. Four steamboat winches had been installed to enable the boats to enter the water quickly.

A separate, large galley was available for passengers in the first to third class and for the heaters. There were pantries near the dining rooms in which food could be kept warm. There were also coffee and tea machines, milk and chocolate cookers, refrigerators and other facilities that ensured that meals ran smoothly and that passengers' individual wishes were satisfied. 32 bathrooms and numerous toilets were distributed across the ship to save guests long walking distances. The processing of the bathtubs for passengers and officers, which were made of nickel-plated copper, was described as an innovation .

For all these reasons, Crown Prince Wilhelm was a great achievement, especially technically, and so the board of directors of Lloyd emphasized the "extremely successful construction" and the "excellent work". At the instigation of the Imperial Navy, the ship was provided with facilities that made it possible, in the event of war, to mount a larger number of guns in order to turn the passenger ship into a cruiser.

The Crown Prince Wilhelm had as its sister ship a hump deck . In this case, the forecastle is more rounded and connected to the side walls not by a sharp edge, but by a curve, so that water that overflows can run off more quickly. This curve at the bow and the two masts fore and aft made it easy to distinguish it from the later built express steamers Kronprinzessin Cecilie and Kaiser Wilhelm II .

Passenger service in the North Atlantic

When the Crown Prince Wilhelm with building no. 249 was launched on March 30, 1901 at AG Vulcan in Stettin , it was the most modern high-speed passenger steamer of its time and impressed with its contemporary lines, which were dominated by the four chimneys. The steamer was one of the first to have a modern telephone system through which it was possible to communicate with all stations from the bridge. In addition, a station for wireless telegraphy was installed for the first time. The Berliner Tageblatt wrote on February 16, 1902: “During the upcoming trip to America ... the eyes of the technical world will be on an inconspicuous apparatus on board the“ Crown Prince Wilhelm ”, which will have to pass its acid test in front of the public. A Marconian telegraph station will be carried, the task of which will be to maintain the connection between the ship on the high seas and the land. "

Eight state and four luxury cabins were reserved for the wealthiest first-class passengers. While the state cabins consisted of a larger room with a separate bathroom, the luxury cabins had a living room, bedroom and bathroom. The first class dining room on the main deck had 414 seats. In addition, first-class travelers had a reading and writing room on the bridge deck. The second-class travelers were accommodated in the stern, with their cabins being distributed over the upper, main and tween decks. These cabins were furnished in the same way as those occupied by the majority of first-class passengers, only the furnishings were a little simpler. As is customary on the steamers of the North German Lloyd, there was always a licensed doctor on board the Crown Prince Wilhelm , who looked after all patients free of charge and, in the US passenger lists, the individual health status of every person on board who wanted to travel to the United States. had to judge.

The ship was intended for the liner service on the route Bremerhaven ( Kaiserhafen ) - Southampton - Cherbourg - New York ( Hoboken ) - Plymouth - Cherbourg - Bremerhaven and should set new standards in travel comfort and speed. Prior to joining the transatlantic passage from 17 September 1901 which was Crown Prince Wilhelm during the period from 7 to 11 September of that year on a luxurious Norway- and Scotland trip with a visit to the cities of Bergen , the Fantoft Stave Church , Edinburgh with The royal seat of Holyrood Palace and the Forth Bridge were used. After returning home, an evening drink offered by the city's Senate took place in the Bremen Ratskeller. Norddeutsche Lloyd had a photo album published for this special trip. The steamer set its first record on May 12, 1902, when it completed the fastest passage of a large liner between Plymouth and Cherbourg to date. On September 16, 1902, Crown Prince Wilhelm broke all expectations and won the Blue Ribbon for the fastest crossing of the North Atlantic to date. It took him 5 days, 11 hours and 57 minutes from Cherbourg to the Sandy Hook lighthouse off Lower New York Bay , with an average speed of 23.09 knots. The Etmale were 349, 574, 574, 581, 573 and 396 nautical miles . Almost exactly one year later, on September 8, 1903, Crown Prince Wilhelm lost the trophy for the fastest westward voyage to the express steamer Deutschland , built in 1900 and owned by the competing HAPAG .

With his sister ship, the Kaiser Wilhelm der Große , he sailed the Atlantic route without major interruptions until the start of the war in 1914, whereby the North German Lloyd had two more luxurious four-chimney high-speed steamers built in Bremen, which also served the scheduled service from Bremerhaven to New York until 1914 . For more tranquil Atlantic passages that took two to three days longer, Lloyd also put a whole fleet of twin-screw saloon mail steamers into service. In total, Crown Prince Wilhelm was able to bunker 4,000 tons of coal, of which around 700 tons were burned every day to keep the machines running.

His last voyage as a passenger steamer on the transatlantic route began for Crown Prince Wilhelm on July 21, 1914 in Bremerhaven; she reached the landing stage of the North German Lloyd in Hoboken / New York on July 29, 1914.

Personalities on board

During his time as a passenger ship, many famous and well-known international personalities of the time sailed with Crown Prince Wilhelm . Among others were on board: the later lawyer and politician Lewis Stuyvesant Chanler Jr. (1903); the opera singer Lillian Blauvelt (1903) ;, the founder of the Chicago Daily News and director general of the Associated Press , Melville Elijah Stone, the Montreal Archbishop Louis Joseph Napoléon Paul Bruchési, and the physicist Ludwig Boltzmann (all 1905), the inventor and writer John Jacob Astor (1906), who went down with the Titanic in 1912 ; the media present, "America's Most Illustrated Woman," Rita de Acosta Lydig and her second husband, Captain Philip M. Lydig (1907); the writer Lloyd Osbourne (1907); the theater director and producer Charles Frohman (1904); the ballet dancer Adeline Genée (1908); Star conductor Alfred Herz (1909); the theater and opera producer Oscar Hammerstein together with the conductor Cleofonte Campanini and the opera singers Mario Sammarco, Giuseppe Taccani and Fernando Gianoli-Galetti (1909); the multimillionaire, politician and lawyer Samuel Untermyer (1910).

The Crown Prince Wilhelm transported according to the documents on Ellis Iceland from 1901 to 1914 approximately 138,526 people to New York, where some of the counted passengers began the trip several times. There is currently no information available about the people transported to Europe.

The state visit in the spring of 1902

On February 16, 1902, Prince Albert Wilhelm Heinrich of Prussia , the brother of Kaiser Wilhelm II, made a state visit from Bremerhaven to New York. He arrived there on February 22nd and was received by US President Theodore Roosevelt and his wife. In a media-effective manner, he did not use the imperial yacht, but the impressive new Crown Prince Wilhelm , on which a large number of press representatives could accompany him. At the same time, 300 cabin passengers and 700 “Zwischendecker” (3rd class passengers) drove with them. This state visit was also an early example of the new medium of film. The first cinematographic reports were made. With this voyage, a new captain began his service on the Crown Prince Wilhelm , August Richter.

Incidents and accidents

September 1901

On the maiden voyage, on September 18, 1901, the day the ship left Cherbourg for New York, Crown Prince Wilhelm was hit by a huge wave in heavy seas and suffered considerable damage, especially to the front superstructure. Among other things, a fan on the foredeck and another on the sun deck was washed away. The wave struck a hole in the wall of the library below the wheelhouse and captain's cabin. Parts of the library and two of the three windows there were destroyed. A window was also smashed on the bridge. Many enthusiastic passengers thanked the experienced captain Ludwig Störmer (1844–1905) that there had been no worse accident. After arriving in America, it was also found that there had been no problems whatsoever with the machines during the journey. Despite the damage, the ship demonstrated extraordinary resilience, which further enhanced her reputation as a reliable and safe liner.

October 1902

In a thick bank of fog, on the morning of October 8, 1902, after his departure from Southampton in the English Channel, Crown Prince Wilhelm collided with the British steamer Robert Ingham , which sank within four minutes. Crown Prince Wilhelm's crew rescued all thirteen crew members with the exception of the mate and a man named Scott, the only passenger on board. In the investigation of the accident was the Maritime Office , "that a fault of the leader was not satisfied of the two ships. The measures taken by "Crown Prince Wilhelm" were appropriate before and after the collision and complied with the statutory provisions. "

December 1903

When Crown Prince Wilhelm moored at her pier in Hoboken on Wednesday, December 23, 1903, coming from Bremerhaven, he was one day late. The cause was the loss of a propeller blade, which had occurred three days after leaving the port of Cherbourg. Therefore the captain had to reduce the speed until New York. On the continuation of the voyage, the steamer was hit by a severe storm that turned into a hurricane on Sunday night, December 20 , which meant that the speed of travel had to be reduced again. The average speed of the ship on this voyage was 17.73 knots compared to the last voyage at 22 knots. With 1,153 passengers, the steamer had carried the largest number of people to the New York harbor in Hoboken on this voyage that had ever come to America during Christmas week. Most first- and second-class travelers planned to vacation in different parts of the United States. Eight port officials brought on board for baggage control had to work well after midnight. There were 983 bags of Christmas mail alone in the storage rooms. Another incident on this voyage was triggered by a Greek passenger who came on board in Cherbourg and brought the smallpox with him. The man was isolated in the ship hospital and taken to hospital on arrival in the United States. 25 fellow travelers had to be quarantined in Hoffman Island for security reasons . Among those arriving was the notorious transatlantic player "Doc" Owens, who had been arrested a few months earlier after playing on an NDL steamer and was now traveling back to the USA under a false name.

March 1905

After Crown Prince Wilhelm arrived in Hoboken on March 16, 1905, Captain Richter declared that this was the stormiest crossing he had ever seen. Six passengers were injured, including a woman so seriously that she had to be treated in the ship's hospital. Oversized waves crashed against the giant ship so hard that it tore five fans overboard and the railing in the front area was bent, destroyed and washed overboard.

July 1907

On Monday, July 8, 1907, Crown Prince Wilhelm under Captain Richter rammed an iceberg on the starboard side at 12:20 p.m. on a trip to New York-Hoboken with 1,172 passengers on board, which had been mistaken for a fog bank. Just about 75 nautical miles north of this point, the Titanic sank almost five years later . Because of the difficult visibility, the speed of the ship had already been reduced significantly to 16 knots, which, in addition to the quick action of the crew, meant that an accident could be avoided. Twenty bulkheads from seventeen watertight compartments had been closed via a control panel (Schottentelegraph) in the map room within thirty seconds of the collision. It turned out that the iceberg had only scratched the paint off the hull and there were tons of ice on the deck. In addition, the lifeboats on the starboard side had been torn away. Three days later, Crown Prince Wilhelm docked at his pier in Hoboken without incident. One of the prominent guests on board on this trip was the long-standing German ambassador to the USA, Hermann Speck von Sternburg .

March 1908

On March 18, a Wednesday, Crown Prince Wilhelm under Captain Nierich was rammed by the British freighter Crown of Castile at 7:25 a.m. at the entrance to Upper New York Bay near Robbins Reef Lighthouse . In thick fog, the Crown Prince had drawn attention to himself with only 392 between deck passengers on board with regular whistles and bells when the accident happened, which fortunately only injured one steward of the passenger liner. The damage was repaired in the New York harbor at the pier of the North German Lloyd in Hoboken. In the subsequent court proceedings, which took place in New York, both ships were found guilty because the Crown Prince Wilhelm was said to have been in an improper position and the cargo ship was going too fast.

June 1908

When Crown Prince Wilhelm arrived in Hoboken on Wednesday June 10, 1908, he had lost another propeller blade during the crossing on June 6. Two days later, a stoker jumped overboard as if “madly through the heat of the boiler room”. Although the Crown Prince Wilhelm immediately turned and a lifeboat was lowered, the man drowned in front of those present.

1914–1915: auxiliary cruiser of the Imperial Navy

After Crown Prince Wilhelm landed in Hoboken on Wednesday, July 22nd, 1914, coming from Bremerhaven and the travelers had left the ship, the crew prepared for the return voyage. On August 3, 1914, news of the state of war with Great Britain and France reached the steamer. A day later, the order came to cancel all passenger bookings. Since the captain of Crown Prince Wilhelm , Burghard Wilhelmi, was on vacation, his first officer, Kurt Grahn, was in command on this trip. Grahn took up more coal for the coming trip than the bunkers could hold. The Crown Prince was designed for a storage capacity of 4,000 tons of coal. Now he should take over 6,000 tons. Therefore, even the richly decorated large saloon of the ship became a coal store. Grahn officially announced that he wanted to return to Bremerhaven. A day later, the British cut the German transatlantic cable. After his departure from New York, Crown Prince Wilhelm met on the high seas with the small cruiser SMS Karlsruhe . From this the ship took over guns, firearms (one MG , approx. 30 rifles), ammunition (including 290 grenades) and a 15-man naval crew. While the equipment was being worked on, the Germans were surprised by the British armored cruiser HMS Suffolk . The equipment was immediately terminated, and both ships departed on different courses. The Suffolk pursued the Karlsruhe . Thanks to their higher speed, the German cruiser was able to escape quickly. From August 6th on, Crown Prince Wilhelm operated as a trade disruptor in the North Atlantic. Its armament consisted of two 8.8-cm guns, two 12-cm guns (the latter, however, were without ammunition) and a machine gun on the navigation bridge . In the following eight months, under the command of Kapitänleutnant Paul Thierfelder, the former navigation officer of the Karlsruhe , he brought up a total of 14 ships with a total of about 56,000 gross register tons, which were sunk.

One of Thierfelder's officers was Lieutenant Alfred Graf von Niezychowski, who did not return home after Crown Prince Wilhelm was interned in the United States, but instead obtained US citizenship and became politically active, among other things. In his book The Cruise of the Kronprinz Wilhelm (German title: Kronprinz Wilhelm, der Luxusdampfer als Kaperschiff ), published in the USA in 1928 , many details of the pirate voyage are described.

On Monday, August 17th, Crown Prince Wilhelm met the freighter Walhalla near São Miguel , the main island of the Azores, and again took over coal and other necessary goods that week. Another takeover of coal took place after September 3, 1914, when the auxiliary cruiser had crossed the equator and met a tender from Karlsruhe , the steamer Asuncion , near the Brazilian Rocas Atoll .

On September 14, 1914, the crown prince , brought about by radio messages from the auxiliary cruiser Cap Trafalgar , reached the scene of the battle between the Cap Trafalgar and the British auxiliary cruiser Carmania near the Brazilian island of Trindade , but the Cap Trafalgar had already sunk by this time. Although he could possibly have put an end to the badly ailing Carmania , the Crown Prince Wilhelm steamed away in order not to become a victim of British warships himself, which had been alarmed by the Carmania's cries for help .

The Sierra Cordoba of the NDL, located in Buenos Aires , was supplied with 1,700 tons of coal, work clothes, shoes and supplies to the Crown Prince Wilhelm . She met the auxiliary cruiser off the Brazilian coast in mid-October 1914. During this transhipment on the high seas, 700 tons of coal changed ships within one day on October 23rd alone. The Sierra Cordoba took over the prisoners on board the auxiliary cruiser, which they brought to Montevideo at the end of November .

The following ships were sunk or attacked by SMS Crown Prince Wilhelm within eight months :

- Fishing schooner Pittan , Russia, home port: Riga

- Commercial steamer Indian Prince , 2,848 GRT, Great Britain, home port: Newcastle; sunk on September 4, 1914

- Steamer La Correntina , 8,529 GRT, Great Britain; Houlder Line, Home Port: Liverpool; Ex line steamer armed with two 4.7-inch rear guns; applied on October 7th and sunk on October 14th, 1914

- Four-masted barque Union , 2,183 GRT, France, Bordeaux; applied on October 28, 1914, sunk on November 22, 1914

- Bark Anne de Bretagne , 2,063 GRT, France, Nantes; applied on November 21st and sunk on November 23rd and 24th, 1914

- Commercial steamer Bellevue , 3,814 GRT, Great Britain, Glasgow; applied on December 4th and sunk on December 20th, 1914

- Commercial steamer Mont Agel , 4,803 GRT, France, Marseille; applied and sunk on December 4, 1914

- Commercial steamer Hemisphere , 3,486 GRT, Great Britain; Hemisphere SS Co. Ltd., Home Port: Liverpool; applied on December 28, 1914 and sunk on January 7, 1915

- Commercial steamer Potaro , 4,419 GRT, Great Britain; Royal Mail Steam Packet Co., Homeport: Belfast; applied on January 10th and sunk on February 6th, 1915

- Liner Highland Brae , 7,634 GRT, Great Britain; H & W Nelson Ltd., home port: London; applied on January 14th and sunk on January 30th, 1915

- Three-masted schooner Wilfred M. , 251 BRT, Great Britain, home port: Bridgetown (Barbados); raised and sunk on January 30, 1915

- Bark Semantha , 2,280 GRT, Norway, Risör; applied and sunk on February 3, 1915

- Commercial steamer Chasehill , Great Britain; applied on February 22, 1915, not sunk, prisoners taken on board

- Commercial steamer Guadeloupe , 6,603 GRT, France, Le Havre; applied on February 23, 1915, sunk on February 24, 1915

- Passenger steamer Tamar , 3,207 GRT, Great Britain, Middlesbrough; applied and sunk on March 24, 1915

- Commercial steamer Coleby , 3,824 GRT, Great Britain, Stockton; applied on March 27th and sunk on March 28th, 1915

Nutritional problems

There was no shortage of food on board the military auxiliary cruiser Kronprinz Wilhelm . According to the dentist and nutritionist Carl Röse (1864–1947), the sailors ate “truly gourmet”. The daily ration consisted of three pounds of meat, white bread, and canned vegetables. Nevertheless, a quarter of the team fell ill with supposed "starvation edema" and became bedridden because the German high command had neglected the warnings from recognized doctors, known for years, to ensure a balanced diet with fresh vegetables and less meat. Low-fiber white bread and canned vegetables boiled for preservation could not provide the necessary nutritional supplements. Röse concluded in his statement about the end of Crown Prince Wilhelm as a warship with the fact that the captain had to drop the flag because of these high failures and call at a US port. It was therefore clear to the dentist: "The German pig has defeated us."

1915–1917 interned in the USA

After a total of eight months at sea, during which the coal supply and the health of the crew posed ever greater problems, the machinery was finally in such poor condition that the captain had the ship interned in the neutral USA in April 1915. On April 11th, Captain Thierfelder took a US pilot on board off the Chesapeake Bay and anchored off Newport News in Virginia on the same day . The crew were interned and the ship mothballed in Philadelphia .

1917–1919 US troop transport

After the USA entered the war on April 6, 1917, the ship was taken into possession on the same day by the authorities of the port of Philadelphia on behalf of the USA. On May 22nd, an ordinance issued by US President Woodrow Wilson retrospectively confirmed this seizure. At the same time, the US Navy was entrusted with converting the ship into a troop transport. After the work was completed on June 9, 1917, Crown Prince Wilhelm was given the new name USS Von Steuben to commemorate the Prussian officer and American revolutionary general Freiherr Friedrich Wilhelm von Steuben . His American berth remained the pier of the North German Lloyd in Hoboken. In the years of its war service for the USA, the Von Steuben was nicknamed Vonnie and was considered one of the most popular ships of the US Navy at the time.

Collision with the USS Agamemnon in 1917

The Von Steuben served the New York – Brest route as a troop transporter . On October 31, 1917, he began his first transatlantic voyage under the US flag with 1,223 soldiers and passengers. On the morning of November 9, around 6:05 a.m., he collided with the troop transport USS Agamemnon and was damaged. The Agamemnon had been the sister ship of Crown Prince Wilhelm and was commissioned in 1903 as Kaiser Wilhelm II . In addition to a dented bow in the upper area, two of its 5-inch cannons and one of its 3-inch cannons were damaged. In addition, sailors had to be rescued from the water who had gone overboard in the collision. The Von Steuben reached Brest three days later at a reduced speed of around twelve knots . Between November 14 and 19, the cargo was unloaded there and repairs were then carried out. So he stayed in Brest until November 28th.

Relief operation after the Halifax explosion in 1917

The Canadian provincial capital Halifax , the hub of military operations and logistics during World War I, experienced the largest non-nuclear explosion in history on December 6, 1917, the Halifax explosion . In a collision, the French ammunition freighter Mont Blanc caught fire and exploded, killing at least 1,635 people and injuring many thousands more. The explosion was so powerful that it triggered a tidal wave and violent earth tremors, while the tremendous shock wave uprooted trees, bent railroad tracks and destroyed numerous buildings, the debris of which was hurled hundreds of meters away. On the morning of December 6th at around 9:14 a.m., Von Steuben , who was coming from Brest, was on her way to the USA around 40 miles from Halifax when the lookout recognized the flames and columns of smoke from the explosion and men were immediately landed in boats to get into the To provide aid and patrol services to the city. The crew of the ship, along with the rescuers dropped by the USS Tacoma (CL-20), were among the first responders shortly after the disaster. The Von Steuben remained at anchor until December 10, before the captain continued the voyage to Philadelphia and arrived there on December 13.

Encounter with U 151 in 1918

On June 18, 1918, the ship was on its way back from Brest to New York when it was ambushed by a German submarine. At around 12.30 p.m., the lookout from Von Steuben reported wreckage. These belonged to the British steamer Dwinsk, sunk by U 151 shortly before . After being shot down, U 151 lay stopped near the manned lifeboats at periscope depth. The German commander's plan had been to use the survivors as bait for possible aid from Allied ships. When the Von Steuben carefully approached the wreckage in a zigzag shape , the seven lifeboats under sail, in which there were survivors to be rescued, were noticed. When the Von Steuben wanted to pick up the survivors 20 minutes after the first report, the machinist Whitney J. Dragon noticed the stern wave of a torpedo that was heading for the Von Steuben . In a dramatic turning maneuver, the ship was turned out of the field of fire and now began to drop depth charges and drive U 151 away.

On June 20, the Von Steuben reached New York and ran out again with fresh troops on June 29. Dragon received a saber of honor on June 21st as an official award for his mindfulness, through which he had saved the lives of 1200 people. An inscription on the scabbard documents its use.

Henderson fire in 1918

On June 30, the Von Steuben formed a convoy with other transporters on its way to France. Around noon on July 2, a fire broke out on board the accompanying Henderson . Von Steuben managed to approach the burning ship and take over more than 2,000 soldiers overnight. The damaged Henderson returned to the United States, while the now overstaffed Von Steuben arrived in Brest on July 9th.

Flu epidemic 1918

On another voyage from New York to Brest in 1918, a flu epidemic occurred among the 2,700 soldiers on board. 400 had to be admitted to the hospital and 34 died.

1919–1924 Commercial service and whereabouts

Between November 10, 1918 and March 2, 1919, the Von Steuben underwent extensive repairs and reconditioning in Brooklyn, New York. He then set sail again with their last captain, Frederick J. Horne (1880-1959), to pick up American troops returning from France. On May 17, 1919, the retreaded troop transport set off again for the USA. Horne remained responsible for these transports until October 13 of the same year.

Although the name of the ship was removed from the list of the US Navy on October 14, 1919, it remained under the United States Shipping Board (USSB) and was named Baron von Steuben . On July 7, 1920, the Shipping Board auctioned the ship for $ 1,500,000 in Washington DC to New Yorker Fred Eggena and the Foreign Trade Development Cruise . The only bidder and new owner wanted to take the ship on a trip around the world to stimulate US foreign trade and bring together 700 American entrepreneurs with foreign markets. The US entrepreneurs had the opportunity to exhibit and demonstrate their offers on board. Eggena estimated around $ 3,000,000 for the repair of the ship. The voyage was to begin on January 15, 1921, with plans to head for several European ports, Buenos Aires, Melbourne, Sydney , Yokohama, Shanghai, Hong Kong, Singapore, Batavia, Rangoon, Calcutta, Colombo, Bombay and Wellington. The ship was to be named United States for this purpose , but the voyage was never made.

After 1921 the steamer became Von Steuben again . In 1923 the ship was removed from the shipping register and sold for scrapping. In 1924 it was broken up by the Boston Iron & Metals Co in Baltimore .

Captains

| No. | Surname | Life dates | On-board service | comment |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Bernhard Friedrich Adolph Ludwig Störmer | January 17, 1844 to July 6, 1905 | September 17, 1901 to December 1901 | On November 15, 1902, Störmer, born in Herzberg am Harz , became a navigation inspector at Lloyd and retired on April 1, 1904. |

| 2 | August Richter | February 1902 to August 1907 | Born in Oldenburg, Richter began his service at Lloyd on March 14, 1881. After completing his 100th ocean crossing on March 6, 1907 in Bremen, he was awarded the Knight's Cross Second Class with a silver crown by the Grand Duke of Oldenburg and a gift of honor from the North German Lloyd. | |

| 3 | Richard Nierich | September 1907 to November 1912 | Nierich joined Lloyd in 1877, became captain in 1889 and was in command of the Bremen from April 1899 . After a physical argument with the 4th officer of the Bremen in New York, Nierich received a reprimand in 1899. In 1904 he was awarded a gift of honor by the North German Lloyd for his 100th ocean crossing. In 1909 Nierich was awarded the bronze medal of the German Seewarte . | |

| 4th | Burghard Wilhelmi | April 1913 to June 1914 | ||

| 5 | Kurt Grahn | 1870 to 1928 | July 1914 to August 6, 1914 | He was first officer on board the Crown Prince Wilhelm and took over her command while Captain Burghard Wilhelmi was on vacation. Grahn died of heart failure in 1928 at the age of almost 60 on the bridge of the NDL steamer Stuttgart . |

| 6th | Lieutenant Captain Paul Wolfgang Thierfelder | 1883 to 1941 | August 6, 1914 to April 11, 1915 | He was the navigation officer of the small cruiser Karlsruhe and took over command of the Crown Prince Wilhelm, which had been converted into an auxiliary cruiser . |

| No. | Surname | Life dates | On-board service | comment |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Lieutenant Charles Herbert Bullock | until June 9, 1917 | Bullock was the senior officer of Crown Prince Wilhelm during her internment at the Philadelphia Navy Yard. | |

| 2 | Lieutenant Commander Stanford E. Moses | August 20, 1872 to October 1950 | June 9, 1917 to September 1918 | Moses was the first American captain of the Von Steuben . |

| 3 | Captain Cyrus R. Miller | September 1918 to May 17, 1919 | ||

| 4th | Captain Frederick Joseph Horne | February 14, 1880 to October 18, 1959 | May 17, 1919 to October 13, 1919 |

Atlantic crossings

The Crown Prince Wilhelm was used in the regular monthly liner service from Bremerhaven to New York and back. When the regular service was suspended due to overhauls and renovations, the sister ships of Crown Prince Wilhelm had to absorb the lack of traffic.

- September 17, 1901 to December 1901 under Captain Ludwig Störmer. In January 1902 there was no trip.

- February 1902 to August 1907: under Captain August Richter. There were no trips in the following months: January 1903; January, February, November, December 1904; December 1905; January, February, November 1906.

- September 1907 to November 1912: under Captain R. Nierich. There were no trips in the following months: January, February, November, December 1908; January, February, November, December 1909; February, March, December 1910; December 1911; March, November 1912; January, February, March 1913.

- April 1913 to June 1914 under Captain B. Wilhelmi. From November 1913 up to and including March 16, 1914 there was no trip.

- July 1914 to July 22, 1914 under Captain Kurt Grahn.

The Schnelldampfer class (Kaiserklasse) of the North German Lloyd before 1914

All four steamers in this class had four chimneys and correspondingly powerful engines with outputs of around 30,000 hp.

- Kaiser Wilhelm the Great (1897 to 1914; 22.35 kn maximum speed, winner of the Blue Ribbon)

- Crown Prince Wilhelm (1901 to 1923; sister ship of Kaiser Wilhelm the Great ; 23.53 kn maximum speed, winner of the Blue Ribbon)

- Kaiser Wilhelm II. (1902 to 1940; 23.58 kn maximum speed, winner of the Blue Ribbon)

- Crown Princess Cecilie (1907 to 1940; 23.6 kn maximum speed)

literature

- Mertens, Eberhard (ed.): The Lloyd Schnelldampfer. Kaiser Wilhelm the Great, Crown Prince Wilhelm, Kaiser Wilhelm II, Crown Princess Cecilie. Olms Presse, Hildesheim 1975. ISBN 3-487-08110-5

- Alfred Graf von Niezychowki: Crown Prince Wilhelm - the luxury steamer as a privateer. Wilhelm Köhler Verlag, Leipzig 1931; translated by Georg von Hase with an introduction by Felix Graf von Luckner .

- Chapter: SM auxiliary cruiser "Kronprinz Wilhelm" In: Eberhard von Mantey : The German auxiliary cruiser . Berlin 1937, pp. 39-86.

- Herbert, Carl: War voyages of German merchant ships . Hamburg, 1934

- Matthias Trennheuser: The interior design of German passenger ships between 1880 and 1940. Hauschild-Verlag, Bremen. ISBN 978-3-89757-305-5

- Thierfelder, Paul Wolfgang: Express steamer "Kronprinz Wilhelm" as an auxiliary cruiser 1914-1915 . Berlin, 1927 (Oceanography. Collection of Popular Lectures, Volume XV, 8, Issue 174)

Filmography

- "Kronprinz Wilhelm" with Prince Henry (of Prussia) on board arriving in New York , documentation, USA, February 1902

Individual evidence

- ↑ a b c d e f News from the shipyards. Launched . In: Oswald Flamm (Red.): Shipbuilding, shipping and port construction. Journal of the Whole Industry in Shipbuilding and Allied Fields No. 13 (April 1901), pp. 509-510; here: p. 509.

- ^ The Crown Prince Wilhelm . In: Scientific American Supplement 1367 (1902), p. 21902.

- ↑ Norddeutschen Lloyd (ed.): The progress of German shipbuilding. The Progress Of German Shipbuilding . Hobbing, Berlin 1909, p. III.

- ^ "Norddeutscher Lloyd, Bremen, yearbook", Verlag HM Hauschild, Bremen 1910, p. 64.

- ↑ Mertens, Eberhard (Ed.): The Lloyd Schnelldampfer. Kaiser Wilhelm the Great, Crown Prince Wilhelm, Kaiser Wilhelm II, Crown Princess Cecilie. Olms Presse, Hildesheim 1975. ISBN 3-487-08110-5 , p. 10.

- ↑ a b Armin Wulle: The Stettiner Vulcan . Koehlers Verlagsgesellschaft mbH, Herford 1989, ISBN 3-7822-0475-1 , p. 41.

- ^ Horst Adamietz, Barbara Fiebelkorn: Gezeiten der Schiffahrt , Verlag H. Saade, 1984, ISBN 3-922642-09-8 , p. 95.

- ↑ a b c d e f News from the shipyards. Launched . In: Oswald Flamm (Red.): Shipbuilding, shipping and port construction. Journal of the Whole Industry in Shipbuilding and Allied Fields No. 13 (April 1901), pp. 509-510; here: p. 510.

- ^ Otto C. Roedder: The electrotechnical equipment of modern ships . CW Kreidel, Wiesbaden 1903. P. 74 ff.

- ^ A b Robert Schachner: The tariff system in the passenger transport of the transoceanic steamship , G. Braun Verlag, 1904, p. 52.

- ^ Otto C. Roedder: The electrotechnical equipment of modern ships . CW Kreidel, Wiesbaden 1903. p. 166.

- ↑ a b c E. and M. Electrical engineering and mechanical engineering. Volume 20 Electrotechnical Association of Austria, Vienna 1902, p. 117.

- ^ Georg Otto Adolf Bessell: Norddeutscher Lloyd , Verlag C. Schünemann, 1957, p. 76.

- ↑ Sunday edition of the Berliner Tageblatt from February 16, 1902, p. 10.

- ↑ Mertens, Eberhard (Ed.): The Lloyd Schnelldampfer. Kaiser Wilhelm the Great, Crown Prince Wilhelm, Kaiser Wilhelm II, Crown Princess Cecilie. Olms Presse, Hildesheim 1975. ISBN 3-487-08110-5 , pp. 53-54.

- ^ Lars U. Scholl: Annual report of the German Maritime Museum 2006. Bremerhaven 2007. New entry in the archive, p. 60.

- ^ The New York Times . May 15, 1902, p. 9.

- ↑ S. Bock: The Blue Ribbon of the Ocean . In: Oswald Flamm (Red.): Shipbuilding, shipping and port construction. Journal of the Whole Industry in Shipbuilding and Related Fields No. 9 (February 1908), pp. 331-334; here: p. 334.

- ^ A b William Lowell Putnam: The Kaiser's merchant ships in World War I. McFarland & Company, Inc. Publishers, Jefferson 2001. ISBN 0-7864-0923-1 , p. 71. (English).

- ↑ a b c The New York Times. of December 24, 1903, p. 3.

- ↑ Ilse Maria Fasol-Boltzmann, Gerhard Ludwig Fasol (ed.): Ludwig Boltzmann (1844–1906). On the hundredth anniversary of death . Springer, Vienna / New York, ISBN 978-3-211-33140-8 , p. 42.

- ↑ a b The New York Times. of March 17, 1905, p. 1.

- ↑ a b The New York Times. of October 31, 1907, p. 3.

- ↑ a b c d e The New York Times. April 14, 1909, p. 11.

- ^ The New York Times. dated June 27, 1909, p. C2.

- ↑ Sunday edition of the Berliner Tageblatt from February 16, 1902, p. 1.

- ^ The New York Times. of September 26, 1901, p. 16.

- ↑ a b morning edition of the Vossische Zeitung of March 6, 1903, p. 12.

- ^ The New York Times. of July 11, 1907, p. 7.

- ^ A b William Lowell Putnam: The Kaiser's merchant ships in World War I. McFarland & Company, Inc. Publishers, Jefferson 2001. ISBN 0-7864-0923-1 , p. 69. (English).

- ^ The New York Times. from March 19, 1908, p. 14.

- ^ The New York Times. August 19, 1908, p. 4.

- ^ The New York Times. dated June 11, 1908, p. 16.

- ^ A b William Lowell Putnam: The Kaiser's merchant ships in World War I. McFarland & Company, Inc. Publishers, Jefferson 2001. ISBN 0-7864-0923-1 , p. 70. (English).

- ^ Robert Rosentreter: Typenkompass Deutsche Kriegsschiffe - Auxiliary cruisers and merchants 1914-1918. Motorbuch Verlag, Stuttgart 2015, ISBN 978-3-613-03774-8 , p. 49.

- ^ William Lowell Putnam: The Kaiser's merchant ships in World War I. McFarland & Company, Inc. Publishers, Jefferson 2001. ISBN 0-7864-0923-1 , p. 74. (English).

- ^ William Lowell Putnam: The Kaiser's merchant ships in World War I. McFarland & Company, Inc. Publishers, Jefferson 2001. ISBN 0-7864-0923-1 , p. 75. (English).

- ↑ JHW Verzijl, Verzijl: "International law in historical perspective: Law of Neutrality V. 10", Martinus Nijhoff Publishers, 1979, ISBN 90-286-0158-9 , p. 255.

- ↑ Uwe Heyll: Water, fasting, air and light . Campus Verlag, 2006, ISBN 3-593-37955-4 , p. 225.

- ↑ See: Logan E. Ruggles (Ed.): History of the Von Steuben and the part she played in the Great War. Ship History Publishing, Hoboken, NJ 1919. The "Vonnie" comes across. In: Our Navy, the Standard Publication of the US Navy . Volume 12, April 1919, pp. 14-16; here: p. 15.

- ↑ a b c d e James L. Mooney (Ed.): Dictionary of American Naval Fighting Ships Volume 4, Government Printing Office, Washington 1981, p. 562.

- ^ Ernest Fraser Robinson: The Halifax Disaster, December 6, 1917. Vanwell Publishing, 1997, ISBN 1-55125-007-1 , p. 46.

- ↑ Alvin Bernard Feuer: The US Navy in World War I. Combat at Sea and in the Air. Praeger Publishers, Westport (Connecticut) 1999, ISBN 0-275-96212-1 , pp. 51-52.

- ↑ The Whitney J. Dragon's Saber of Honor. Auctioned on eBay in 2008 , documented on www.worthpoint.com; accessed on March 28, 2015.

- ↑ a b c James L. Mooney (Ed.): Dictionary of American Naval Fighting Ships Volume 4, Government Printing Office, Washington 1981, p. 563.

- ^ The New York Times. 8 July 1920, p. 9.

- ^ The New York Times. dated August 6, 1920, p. 8.

- ^ The New York Times. of May 4, 1924, p. 10.

- ^ The New York Times. 7 July 1905, p. 7.

- ↑ Reinhold Thiel: The history of the North German Lloyd 1857-1970. Volume 3, Verlag HM Hauschild, 2004, ISBN 3-89757-166-8 , p. 64.

- ^ The New York Times. of February 21, 1907, p. 7.

- ^ Vossische Zeitung (evening edition) of March 6, 1907, p. 4.

- ^ Christian Ostersehlte: Hoboken, June 30, 1900. A fire and ship disaster near New York and its late reception. In: Historical Images. Festschrift for Michael Salewski on his 65th birthday . Franz Steiner Publishing House. Stuttgart 2003. ISBN 3-515-08252-2 , p. 584.

- ^ Christian Ostersehlte: Hoboken, June 30, 1900. A fire and ship disaster near New York and its late reception. In: Historical Images. Festschrift for Michael Salewski on his 65th birthday . Franz Steiner Publishing House. Stuttgart 2003. ISBN 3-515-08252-2 , p. 581.

- ^ Reinhold Thiel: The history of North German Lloyd 1857-1970 , Volume 3, Verlag HM Hauschild, 2004, ISBN 3-89757-166-8 , p. 128.

- ↑ a b Time magazine of October 1, 1928.

- ↑ Hildebrand, Röhr, Steinmetz The German warships .

- ↑ Logan E. Ruggles (Ed.): History of the Von Steuben and the part she played in the Great War. Ship History Publishing, Hoboken, NJ 1919, p. 11.

- ↑ Logan E. Ruggles (Ed.): History of the Von Steuben and the part she played in the Great War. Ship History Publishing, Hoboken, NJ 1919, p. 19.

- ↑ Obituary: Capt. Stanford E. Moses, USN In: The Army, Navy, Air Force Journal. Volume 88, Issues 27-52, 1951, p. 1064.

- ↑ Logan E. Ruggles (Ed.): History of the Von Steuben and the part she played in the Great War. Ship History Publishing, Hoboken, NJ 1919, p. 7.

- ^ Army-Navy-Air Force register and defense times. Volume 65, May 17 1919, p. 630. ( Online ).

- ↑ Mertens, Eberhard (Ed.): The Lloyd Schnelldampfer. Kaiser Wilhelm the Great, Crown Prince Wilhelm, Kaiser Wilhelm II, Crown Princess Cecilie. Olms Presse, Hildesheim 1975. ISBN 3-487-08110-5 , p. 65 (reprint of the 1914 timetable).