Cape Hornier

A Cape Hornier , Kaphoornier or Cape Horner (English Cape-Horner ; French Cap Hornier ) is in the narrower sense a sailor who circumnavigated Cape Horn on a freighter that is not equipped with an engine or auxiliary engine . The term is also used for the ships themselves; in a wider sense, occasionally for all ships and people who have circled Cape Horn.

Until 2003 there was a worldwide association of Kaphoorniers, the international brotherhood of captains on long voyages, Kaphoorniers ( AICH for short from French Amicale Internationale des Capitaines au Long Cours, Cap Horniers ), among other things with a German department that covers a large part of the belonged to German Kaphoorniers. The association was founded in 1937 in Saint-Malo , France , and was dissolved because almost all Kaphoorniers have now died. A successor organization still exists in Chile , on whose territory Cape Horn is located. In several countries there are also smaller groups of Kaphoorniers who used to belong to the International Brotherhood and who continue to meet informally.

Challenge Cape Horn

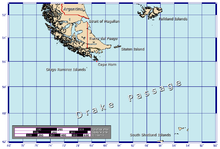

The southern bypass of Cape Horn is notorious, especially for sailing ships, as one of the most dangerous shipping routes in the world. Located at about 55 ° 59 ′ south latitude on the southern tip of South America, the cape is located in a region with frequent and violent storms (in summer 5%, in winter even up to 30% of the time) and often high seas (in summer under 15% of the time over 3.5 meters high, in winter over 30% of the time). The main reasons for this are the strong winds and the ocean currents that cover up to 50 nautical miles a day, which circle the earth between around 40 and 60 degrees of latitude in the southern hemisphere, almost unhindered by land masses. The widely projecting to the south tip of South America and to a lesser extent the her from the Antarctic meet outstanding Graham Land act like a funnel through which the marine and air currents in the Drake Passage crowded together in the south of Cape Horn, while by the so-called. Kapeffekt be accelerated. Since Cape Horn is much more southerly than the southernmost points of Africa ( Cape Agulhas ) and Australia ( Southeast Cape in Tasmania and South Cape in New Zealand ), the effect on this cape is particularly pronounced. For the ocean currents, the effect is reinforced by the flatter seabed between Cape Horn and Grahamland.

In the Cape region there are also often difficult weather conditions due to turbulent low pressure areas from the Andes : Depths that move from west to east far north of Cape Horn are deflected by the 4,000 meter high Andes to the south or south-east and then shift around the south Land mass around. The relatively shallow waters near the cape are also problematic. In addition, due to the danger of icebergs, ships cannot travel south indefinitely in order to avoid the Cape and its storms extensively. Especially in the southern winter, storms, wetness and cold (even in summer only up to 10 ° C) result in harsh and often dangerous weather conditions. "Even the devil would freeze to death in this hell," Charles Darwin is said to have said about Cape Horn. And an experienced Cape Horn captain summed up Cape Horn: “... the wind is harder there, the [wind] changes faster, the nights longer, the swell higher, the ice closer ... You don't get any sleep. You get so wet for so long that the skin with your socks will peel off when you have the time to take them off. But with luck you can pass Cape Horn and with God's grace you don't kill anyone. "

According to European statistics, more than 800 ships have sunk in the Cape Horn region and over 10,000 people have lost their lives there. This means that Cape Horn is home to the largest ship cemetery in the world.

The circumnavigation of Cape Horn is very difficult in both directions, but due to the westerly winds, which prevail 75% of the time, it is often very tedious and dangerous, especially in the east-west direction. For a full month - from March 23rd to April 22nd, 1788 - William Bligh , captain of the Bounty , tried to circumnavigate Cape Horn on the way from England to Tahiti in an east-west direction. Because of the opposing storms, Bligh finally abandoned the attempt and instead chose the much longer route around Africa and Australia. It is unclear to what extent the hard time off Cape Horn and the length of the detour contributed to the displeasure of the crew, which finally culminated in the famous mutiny at the beginning of the planned return trip to England. The record for the longest circumnavigation of Cape Horn (traditionally the time from reaching the 50th parallel south latitude in the South Atlantic to reaching the same latitude in the South Pacific, or vice versa on the return voyage to Europe) is held by the full ship Susanna of the Hamburg shipping company G. JH Siemers & Co , which in the southern winter of 1905 needed a full 99 days for the circumnavigation in an east-west direction; 80 days of them there was a storm with 10 or more Beaufort . For comparison: The Priwall managed the fastest circumnavigation under Captain Adolf Hauth in November 1938; it lasted - also in the normally lengthy east-west direction - only 5 days and 14 hours. Ships like the Ukrainian windjammer Khersones are still trying to undercut this time around 1997 with 5 days and approx. 21 hours, at least in the "faster" west-east direction.

The weather conditions are also responsible for the fact that many sailors who circumnavigated Cape Horn have never seen the Cape themselves. Especially in bad weather, the ships avoided many miles to the south to be on the safe side. This was particularly the case before the introduction of modern navigational instruments such as GPS , when navigators determined their position using the position of the sun and stars ( astronavigation ); Persistently bad weather inevitably led to less precise position determinations, so that greater safety distances were necessary. In addition, Cape Horn is often invisible even from close proximity: while poor visibility is unusual in summer, it can drop to half a nautical mile (approx. 1 km) in winter.

The extinction of the Kaphoorniers

The Kaphoorniers are about to die out due to a lack of offspring: the last freighter without an auxiliary engine to circumnavigate the Cape was the Pamir on July 11, 1949 . Several reasons are responsible for the "extinction" of the Kaphoorniers:

The passage around Cape Horn has lost its importance for freight shipping since the completion of the Panama Canal in 1914. Before that, almost all shipping traffic ran around the cape between the South and North American west coast on the one hand and Europe, Africa and the South and North American east coast on the other, but also between the American east coast and Australia and East Asia. The only alternative to this was the longer route around Africa and Asia. From the 19th to the middle of the 20th century, journeys for the saltpetre transport from Chile and for the wheat transport from Australia (see wheat regatta ) also led around Cape Horn. With the decline in the economic importance of these goods in Europe, so did the number of cargo ships that sailed the route around Cape Horn.

In addition, in the 20th century, the cargo sailors were increasingly displaced by steam shipping. The last windjammers on cargo voyages were the Pamir (sunk in 1957), the Passat (taken out of service in 1957) and most recently the Omega (ex Drumcliff ; sunk in 1958); in the last years of their service they were no longer used around Cape Horn. Since then, commercial sailing ships have only operated in some regions of the world, e.g. B. the dhows on the coasts of the Indian Ocean or the Chinese junks . They can no longer be found on long intercontinental routes. Tall ships that still circumnavigate Cape Horn are, however, tourist ships or sailing training ships without cargo.

In addition, all windjammers still sailing today are equipped with a machine drive. That alone violates the statutes of the International Brotherhood of Kaphoorniers. In addition, the auxiliary engines are also often used by tall ships traveling for tourists when they bypass Cape Horn , so that probably only very few circumnavigations take place alone under sails: the inexperienced crews, mostly consisting of amateurs , could do the sailing maneuvers among the often Otherwise do not execute the prevailing storm conditions. However, some tall ships still manage parts of the passage without motor power. So happened z. B. the Alexander von Humboldt on January 19, 2006 Cape Horn under sail in an east-west direction, but did not sail the entire distance from the 50th to the 50th parallel. In the opposite west-east direction, for example, the full ship Khersones managed to circumnavigate under sail on January 26, 1997.

Worldwide there were probably 150 Kaphoorniers organized in the International Brotherhood in 2003, 68 still lived in Germany. A year later, when the German branch of the Kaphoornier Brotherhood was dissolved, there were only 50, and today there are probably significantly fewer. Heiner Sumfleth, the last president of the International Brotherhood, died in October 2005. Worldwide there are still groups of Kaphoorniers in Chile, probably due to the geographic proximity to the Cape, and the Åland Islands, the home port of the shipowner's Gustaf Erikson's last windjammer fleet . The number of Kaphoorniers still alive who did not belong to the International Brotherhood is not known.

The Kaphoorniers still living today circumnavigated Cape Horn as young men or even as minors, like the youngest Kaphoornier at the time, Wolfgang Loehde, who was already 14 years old on a commercial sailing ship. Accordingly, the number of Kaphoorniers who circled Cape Horn on a freighter without an auxiliary engine as a captain fell even earlier: In 1989, Gottfried Clausen from the Commodore Johnsen , today's Sedov , was the last German to succeed; worldwide their number was already estimated at four or five in 1994.

Even today there are only a few of the sailing ships that circumnavigated Cape Horn on cargo voyages without a motor. Most were later lost on their journeys (e.g. Pamir , Duchess Cecilie ) or were scrapped. Some ships are still preserved as museum ships (e.g. Passat , Pomerania ). Only very few Kaphoorniers, however, are again ( James Craig ex Clan Macleod ) or even still ( Sedov ex Commodore Johnsen ex Magdalene Vinnen II , Kruzenshtern ex Padua ) in service as sailing ships.

The International Brotherhood of the Kaphoorniers

The later worldwide association of the Kaphoorniers was founded in Saint-Malo in 1937 as the “Circle of Friends” or “Brotherhood of Captains on Long Voyages, Kaphoorniers” - French Amicale des Capitaines au Long Cours, Cap Horniers . H. still without the later addition international . A year earlier, several French captains who had circumnavigated Cape Horn had met at the invitation to dinner with their former hydrography teacher Georges de Lannoy. They had decided to keep meeting and to keep the memory of the circumnavigation of the cape alive. As a result, 35 French Kaphoorniers founded the Brotherhood of Kaphoorniers in Saint-Malo in May 1937. Initially, the brotherhood was only intended for captains, but later also seamen were admitted who had only acquired their master's license for long voyages after circumnavigating Cape Horn . The name is mostly translated as the International Brotherhood of the Kaphoorniers (see English International Brotherhood Captains Cap-Horners ); Literally from French, however, it would be more International Friends or International Circle of Friends of Captains on Long Voyages, Kaphoorniers .

After the Brotherhood's activities were suspended during World War II , French captains met again. In the following years, first Belgians, then British and Germans joined the Kaphoorniers. In 1951, the brotherhood was therefore renamed Amicale Internationale des Capitaines au Long Cours, Cap Horniers ( International Circle of Friends / Brotherhood of Captains on Long Voyages , Kaphoorniers ; AICH for short ). At that time the brotherhood had about 800 members. They decided to hold their meetings in a different country each year.

Soon other nations joined the Kaphoorniers. Over the years there have been active departments ("Sections") in Åland (from 1961), Australia, Belgium (from 1949), Germany (from approx. 1951), France (from 1937), Chile (from 1989), Denmark, Great Britain (from 1951), Finland (from 1965), Italy, New Zealand, Norway, the Netherlands (from 1959), Sweden and North America (joint division of Canada and the USA, from 1993). At least one of the annual international meetings was held in all departments except North America, with the majority of 22 being held in France.

The International Brotherhood had its heyday in the 1950s and 1960s. In the 1950s they had about 2,600 members, including 672 Germans.

Goals of the Brotherhood

The aim of the brotherhood was contact and camaraderie among seafarers who had the special experience of circumnavigating Cape Horn. According to the Chilean Kaphoornier department, this was intended to preserve the memory of the ships with which the circumnavigations were carried out, as well as those of their crews and their courage and skills.

In addition to the interest in cherishing memories from the great days of the windjammers, the Kaphoorniers also repeatedly set themselves the task of commemorating the seamen who died at sea. For example, the German department (section) was involved in building the Madonna of the Sea memorial at the Altona fish market in 1985 , which is dedicated to the almost 26,000 seafarers who died in German fishing and merchant shipping over the past 100 years . A smaller copy of the figure was set up in November 2001, as part of an international meeting in Chile, by the German Kaphoorniers in the chapel on the island of Hornos , where Cape Horn is located.

In keeping with its objectives, the International Brotherhood collected documents on the lives of the Kaphoorniers in the course of its existence. When it was dissolved, it transferred the documents to a museum housed in the Tour Solidor in Saint-Malo and dedicated to long-distance seafaring and in particular to the history of the circumnavigation of Cape Horn.

Brotherhood motto, symbols and title

The motto of the International Brotherhood was Vive l'esprit de Saint-Malo , in English Long live the spirit of Saint-Malo . The Kaphoorniers used this to describe the atmosphere of friendship and cross-national camaraderie that they found characteristic of the community of the brotherhood and their mutual meetings. The expression comes from a German captain who went to Le Havre in 1955 for a Kaphoornier meeting . Unsure of how he would be received as a German by the French captains after the Second World War, he was impressed by the warm welcome he received and concluded his acceptance speech with the words Vive l'esprit de Saint-Malo . The information varies as to whether the captain was Walther von Zatorski , who had traveled alone, or, as the Chilean Kaphoornier successor organization reports, Carsten Rosenhagen, who, together with 13 other Germans, was invited to Le Havre and Rouen followed. In any case, the saying was taken up and became the motto of the Kaphoorniers. Its meaning and origin therefore have nothing to do with the expression “ Geist von Saint-Malo” of EU defense policy. The Kaphoornier Hans Peter Jürgens summarized in an interview: “The spirit of St. Malo is the spirit of international understanding and comradeship. The knowledge that everyone can only master the challenge of the stormy seas off Cape Horn together. "

The symbol of the Kaphoorniers is the albatross - a large seabird that lives mainly in the southern hemisphere and only visits solid land to breed. The tall ship sailors traditionally felt a bond with the Albatross. Albatrosses often followed the ships long distances across the oceans. According to old seaman beliefs, the souls of sailors who have died at sea also take on the shape of an albatross. Although albatrosses could have been hunted on board as a welcome replenishment of food supplies, as James Cook did in 1772, the sailors' belief of the crews of the tall ships made killing an albatross taboo. This custom probably dates back to at least the late 18th century; as early as 1798, Samuel Taylor Coleridge immortalized the - artistically exaggerated - discomfort of having killed an albatross in his famous poem The Rime of the Ancient Mariner ( ballad from the old sailor , The old sailor or The old sailor ).

The logo of the International Brotherhood is the head of an albatross with a square metal bait in its beak. The motif bears the lettering AICH St. Malo . The choice of images goes back to the pastime common on some windjammers of luring albatrosses to a bait: a square piece of metal with a bait was attached to a long line , the other end of which was held on board. If the albatross had eaten the bait and the line was held taut, the bird with its bent beak could not get away from the piece of metal. Similarly, Cook wrote in his logbook in 1772 that they "caught albatrosses (...) with the poker", although at that time they were still used for hunting. The albatrosses allegedly let themselves be led behind the ship like paper kites by the square pieces of metal from the windjammer era. Gradually they were then pulled on board, where they were released after a while. To harm them or even kill them would have been unthinkable out of respect for the bird.

The Albatros was also used in the Brotherhood to refer to those who had circled Cape Horn on a tall ship on a cargo voyage without an auxiliary engine as a captain ; only as an exception was the honorary title awarded to a Kaphoornier who had served the association as president for many years, namely to the German Heiner Sumfleth. Seafarers who were officers on these ships were named after a smaller subspecies of the albatross family Malamok (English Mollyhawk ). According to the Chilean Association, however, the name Malamok is reserved for those who circumnavigated the Cape as an officer or part of the crew and were later promoted to captain. The third name is the Cape dove , another species of bird from the southern hemisphere. In some departments (Chile, Finland), the Cape Pigeons are the Kaphoorniers who have never acquired a captain's license. In the German section of the Brotherhood, however, this title was given to the wives and widows of Kaphoorniers, whereas the simple Kaphoorniers, who never became captain, were simply called voilier (French for 'sailors').

The president of the Brotherhood were as Grands Mâts (fr. For, large booms '), respectively. They were Louis Allaire, Charles Fourchon, Léon Gautier, Marcel Legros, Raymond Lemaire, Yves Menguy, Jean Perdraut, Verner Ojst and from 1996 until the dissolution of the German Heiner Sumfleth. Louis Allaire and Yves Menguy had also been among the founders of the brotherhood.

Dissolution and succession of the brotherhood

Due to the age structure, the International Brotherhood was abolished on May 15, 2003 in Saint-Malo. At that time there weren't even 400 members worldwide, and the median age was 87 years. In September 2004, at a final meeting in Hamburg, the German section of the Kaphoorniers, to which 700 Kaphoorniers had temporarily belonged, was also dissolved. In October 2005 Heiner Sumfleth, the last Grand Mât (President) of the international association, died in October 2018, the last chairman of the German association, Hans Peter Jürgens .

Several national divisions still exist as Kaphoorniers' regional organizations. The Chilean successor association, which has opened up for all kinds of captains who have circled Cape Horn, is still active. On April 20, 2009 the writer and journalist Wolf-Ulrich Cropp was registered under membership no. C-058 inducted into the Chilean Brotherhood of Caphorniers . Cropp circumnavigated Cape Horn on January 26, 1997 on the three-masted full ship Khersones. Extraordinary membership is also open to seafarers who have circumnavigated the Cape on a yacht. There is also a larger group of Kaphoorniers on the Åland Islands around Mariehamn , the home port of Gustaf Erikson's last fleet of windjammers .

Movies

- Peter Lohmeyer : On windjammers around the Cape . VHS. 48 min. Delius Klasing

- Michael Schomers : At the end of the world: Cape Horn . NDR / ARTE , 60 min, 2002 (book: Michael Schomers / Wolfram Engelhardt, production: Lighthouse Film, Cologne / Unkel)

literature

General representations of the Cape Horn circumnavigation:

- Fritz Brustat-Naval : The Cape Horn Saga. On sailing ships at the end of the world. Ullstein Taschenbuch 20 831 Maritim , Frankfurt am Main / Berlin 1987, ISBN 3-548-20831-2 .

- Wolf-Ulrich Cropp: Gold Rush in the Caribbean - In the footsteps of Francis Drake around Cape Horn on the "Khersones" 1997 . Klasing, Bielefeld 2000, ISBN 3-7688-1175-1 .

- Ursula Feldkamp (Ed.): Around Cape Horn . With freighter to the west coast of America. Hauenschild, Bremen 2003, ISBN 978-3-89757-210-2 (on the occasion of the permanent exhibition in the German Maritime Museum , Bremerhaven, "Around Cape Horn with cargo sailors to the west coast of America" - opened on November 30, 2003).

- Eigel Wiese: men and ships off Cape Horn. Koehlers, Hamburg 1997, ISBN 3-7822-0689-4 .

Reports from Cape Horniers:

- Francis Chichester : Along the Clipper Way. Coward McCann, New York 1966, ISBN 0-340-00191-7 (Chapter 15: Cape Horn , English).

- Wolfram Engelhard: Cap Horniers, The last sailors from Cape Horn . DSV, Hamburg 2001, ISBN 3-88412-350-5 .

- Isaac Norris Hibberd: Sixteen Times Round Cape Horn: The Reminiscences of Captain Isaac Norris Hibberd. Mystic Seaport Museum, Mystic CT 1980, ISBN 0-913372-15-3 .

- Eric Newby : The Last Grain Race . Lonely Planet Publications, Hawthorn 1999, ISBN 0-86442-768-9 (English).

- Joris van Spilbergen: East end West Indian Spieghel . Jan Janssz, Amsterdam 1621. (Jacob Le Maires' travel description from 1621 with original maps and illustrations).

- William F. Stark: The Last Time Around Cape Horn: The Historic 1949 Voyage of the Windjammer Pamir . Carroll & Graf, New York 2003, ISBN 0-7867-1233-3 (English).

Web links

- Chilean Kaphoornier Association (English and Spanish; individual pages in French; also contains articles on various maritime topics, e.g. on some windjammers)

- Dutch Kaphoornier Association (Dutch, entry page also in English)

- Finnish Kaphoornier Association (Finnish)

- La tour Solidor, St. Malo (English and French; Museum of Long Distance Seafaring and in particular the circumnavigation of Cape Horn)

- Cape Horn Farewell (Farewell to Cape Horn) (website about the Cape Horn trip of the last Kaphoorniers in 2001; photos with English overview; several German articles about the trip and generally about Kaphoorniers under publications )

Individual evidence

- ^ A b Francis Chichester : Along the Clipper Way. Coward McCann, New York 1966, ISBN 0-340-00191-7 , pp. 136-137 (English)

- ↑ Kai Müller (May 11, 2003): What did they want at the end of the world. in Der Tagesspiegel online (accessed March 9, 2007)

- ↑ a b c d Hans Wille: The sad end of an era. The elderly brotherhood of Cape Horniers meets for the last time. In: Berliner Zeitung , May 16, 2003

- ↑ Own translation of: [You've noted the way cyclonic movements race across the Southern Ocean - Indian or Pacific, it's much the same. You've learned the signs for shifts of winds - the slight clearing in the south-western sky, a movement in rising cloud, then the swift sudden shift. It's the same off the Horn, except] the wind is madder there, the shifts faster, nights longer, seas higher, ice nearer ... You get no sleep. You'll get so wet for so long that your skin will come off with your socks, if you get the time to take them off. But with luck you'll get past Cape Horn and by the grace of god, you won't kill anybody. (The square brackets added here denote the part of the quote that was not translated and is only given here for the context of) - Quote from an experienced Cape Horn captain according to the US Navy Marine Climatic Atlas of the World (Version 1.1 August 1995) (PDF; 190 kB) accessed March 9, 2007

- ↑ Logo Amicale , on the website of the Chilean Kaphoorniers (English and Spanish; accessed March 9, 2007)

- ↑ Experience report of the Cape Horn tour: Wolf-Ulrich Cropp: Gold rush in the Caribbean . Delius Klasing Verlag, Bielefeld 2000, ISBN 3-7688-1175-1 , Chapter 11, S, 143-153, with photo documentation.

- ↑ a b Bjoern Moritz. Cape Horn , on Moritz ' Seemotive website (accessed March 28, 2007)

- ↑ a b c Helmut Schoenfeld: Maritime memorial culture. Maritime memorials on the edge of Hamburg's port. in: OHLSDORF - magazine for mourning culture. Ohlsdorf 4.2005, No. 91. ISSN 1866-7449 (also online, accessed March 9, 2007)

- ↑ a b c d Amicale Internationale - Cape Horners , on the website of the Chilean Kaphoorniers ( Memento of September 27, 2007 in the Internet Archive ) (English; accessed March 30, 2006)

- ↑ a b History . ( Memento of February 18, 2007 in the Internet Archive ) Website of the Brotherhood of the Kaphoorniers in Saint-Malo (English) accessed March 9, 2007

- ↑ a b Saint Malo's Spirit , on the website of the Chilean Kaphoorniers ( Memento from September 27, 2007 in the Internet Archive ) (English; accessed March 29, 2007)

- ↑ In 1998 Great Britain and France met in Saint-Malo to talk about the political and military weakness of the European Union, which had become evident in the Balkans conflict . They came to the decision that the European Union should develop “the capacity for autonomous action, backed up by credible military forces, the means to decide to use them, and a readiness to do so, in order to respond to international crises”. Manuel Vázquez Muñoz: Searching for a safer Europe. UNISCI Discussion Paper . ( Page no longer available , search in web archives ) Info: The link was automatically marked as defective. Please check the link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. (PDF) Accessed January 29, 2007. French version of the Saint-Malo Declaration . (PDF)

- ^ Helmut Schoenfeld (November 15, 2005). Subject: Maritime memorial culture. Maritime memorials on the edge of Hamburg's port. Ohlsdorf magazine for mourning culture (issue No. 91, IV, 2005). (accessed March 9, 2007); AICH emblem , on the website of the Chilean Kaphoorniers ( Memento from June 15, 2011 in the Internet Archive ) (English; accessed March 9, 2007)

- ↑ a b Thursday, November 24th [1772] - … Many albatrosses over the ship, some of which we caught with the poker and which were welcome as a change in the diet, even at a time when all auxiliary workers were being supplied with fresh sheep meat … - James Cook's log, according to A. Grenfell Price (2005). James Cook. Discovery trips in the Pacific. Edition Erdmann. (P. 128), ISBN 3-86503-024-6 .

- ^ Samuel Taylor Coleridge (1798). The Rime of the Ancient Mariner / Ballade vom alten Seemann , English and German parallel version on the website lyrik online (possibly own translation from English; accessed March 29, 2007); English version in an official publication: Samuel Taylor Coleridge (1798/2001). The Rime of the Ancient Mariner . (German Ballad of the Old Sailor , The Old Seafarer or The Old Sailor ) ( Memento June 6, 2007 in the Internet Archive ) Electronic copy of the electronic text center of the University of Virginia Library. (English) accessed March 29, 2007

- ↑ a b c A.ICH emblem . ( Memento from June 15, 2011 in the Internet Archive ) on the website of the Chilean Kaphoorniers (English) accessed March 9, 2007

- ↑ Titles of Amicale , on the website of the Chilean Kaphoorniers ( Memento of September 27, 2007 in the Internet Archive ) (English; accessed March 9, 2007)

- ^ Titles of Amicale , on the website of the Chilean Kaphoorniers ( Memento of September 27, 2007 in the Internet Archive ) (English; accessed March 31, 2006); List of members of the Finnish Kaphoorniers (accessed March 9, 2007)

- ↑ Manfred Senf (April 20, 2003): The albatross is her heraldic animal. The last Cape Horn sailors still have a regular table in the Hamburg captain's cabin. Evangelische Zeitung-online , issue 167/03; Svante Domizlaff (3rd November 2001). The end of the myth about Cape Horn in the Hamburger Abendblatt (both accessed March 9, 2007)

- ↑ Svante Domizlaff: The end of the myth about Cape Horn . In: Hamburger Abendblatt , 3/4. November 2001, accessed March 9, 2007

- ↑ Probably on September 15, 2004: On the website www.janmaat.de it says with reference to an unspecified “press release from September 15, 2004” (a Wednesday) that the Kaphoorniers met “on Wednesday evening” for the last time would have. - Der Küstenschnack 2004 (section Cap Horniers dissolve after 50 years of alliance in Germany ) on www.janmaat.de (accessed March 31, 2007)

- ^ Stefan Krücken: Captain Hans Peter Juergens: The last Cape Hornier disembarks . In: Spiegel Online . October 17, 2018 ( spiegel.de [accessed October 18, 2018]).