Chough

| Chough | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Chough ( Pyrrhocorax pyrrhocorax ) on La Palma |

||||||||||||

| Systematics | ||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||

| Scientific name | ||||||||||||

| Pyrrhocorax pyrrhocorax | ||||||||||||

| ( Linnaeus , 1758) |

The Chough ( Pyrrhocorax pyrrhocorax ) is a bird art from the family of corvids (Corvidae). The black-plumed birds with narrow, curved red bills were native to large parts of Eurasia during the last glacial period . Today they can mostly only be found in the mountains, highlands and coastal regions of the Palearctic and Ethiopia . Particularly due to the change in agriculture from the 19th century, the species declined even further in Europe. Their habitat consists of pastureland and open areas with low, sparse grass vegetation. The Chough is mainly dependent on a sufficient supply of rock niches for breeding. It feeds mainly on seeds and berries as well as on insects and other invertebrates. The species forms monogamous, lifelong breeding pairs and usually builds their nests on roofed ledges, but sometimes also in building niches or animal structures. The clutch size varies between one and six eggs, the female usually lays three to five eggs.

The first description of the alpine crow by Carl von Linné comes from the year 1758. Its closest relative is the alpine chough ( Pyrrhocorax graculus ), with which it forms the genus of the mountain crows ( Pyrrhocorax ). A total of eight recent and one extinct subspecies are distinguished, but their delimitation is often problematic. Although the Chough is not considered to be threatened globally, its population in Europe continues to decline. The species is therefore the subject of conservation programs in several countries.

features

Build and color

With a body length of 38–41 cm, the Alpine crow is one of the medium-sized representatives of the corvids. It is slim built and is characterized above all by its long legs and the narrow, elongated and curved beak. As is typical for mountain crows, it lacks the paneling on the legs that is common with other corvids. The nasal bristles are extremely short and barely cover the nostrils. Females are, on average, slightly smaller than males from the same population. As a rule, Choughs are the largest in the Himalayas and the smallest are birds in the British Isles . Weight and size generally increase with latitude and altitude. Depending on the region, females reach a weight of 230–390 g and a wing length of 266–323 mm. The female tail measures 125–150 mm, its beak (measured from tip to base) 47–58 mm long. The barrel bone of female birds measures between 48 and 56 mm. Male alpine crows weigh between 230 and 450 g when fully grown and reach wing lengths of 253–357 mm. Their tail becomes 120–166 mm long. The beak of adult males measures 51–70 mm, their barrel is 49–63 mm long.

There are no differences in color between females and males. Both sexes have a deep black, shiny age dress, a red beak and red legs. The metallic shimmer of the close-fitting plumage is different depending on the population and can be bluish or greenish. Over time, the feathers lose their luster and saturation and fade to a dull brown before they are replaced with new ones during the next moult . The beak and legs are crimson red in adult birds . Their irises are dark brown, their claws black. Young animals differ from adult birds in their shorter and looser plumage. They lack the metallic sheen of adult individuals and their plumage appears lighter and dirtier. Until the first autumn, juvenile Choughs have a rather orange beak, which is significantly shorter than that of adult individuals. Slight differences can also be seen in the claws of the young animals, which are rather dark brown and have a light tip.

The reddish color of the beak and legs inspired various legends in European folklore. In medieval and early modern Great Britain, for example, the birds were regarded as Arthur 's revenants , still stained red from the blood of his last battle. British popular belief also suspected them of being arsonists because of their red beaks and legs, which was borne out by observations of brooding Alpine crows who carried twigs or straw - alleged fuel - into buildings. Their characteristic appearance also made the Chough a coat of arms regionally, for example for Cornwall or Thomas of Canterbury .

Flight image and locomotion

Alpine crows are agile and versatile fliers. In flight, they differ from Alpine choughs mainly in their rectangular and deeply fingered wings, the straight rear edge of the tail and the longer neck and beak. In cross-country flights, they fly faster than ravens and crows ( Corvus spp.), But resemble them in their even, powerful wing beats. The Chough often engages in acrobatic flight maneuvers. For example, it performs dives at speeds of up to 100 km / h, which it only slows down shortly before the ground. The animals are able to fly almost vertically upwards or against winds of force 9. The Chough usually performs its flight maneuvers close to cliffs or just above the ground, while the closely related Alpine chough prefers the open air space. On the ground, the species walks with a measured step or hops in great leaps. In a hurry she lapses into the triple pace typical of corvids, where she hops, puts both legs down in quick succession and then hops again. Unlike many species in the family, the Chough hardly uses trees or bushes to sit down and spend most of their time on the ground.

Vocalizations

Whistling, chirping or squeaking calls shape the sound repertoire of the alpine crow. They can be stretched or choppy, melodious or rough, but usually differ significantly from the croaking or flirtatious vocalizations of other corvids. Many calls of the species are also known from the Alpine chough, but apparently fulfill other functions in communication there. The vocabulary of the Chough is considered complex because it is very variable and the same call can convey different messages depending on the context, individual or intonation. A common call is the so-called trill as griää , tschiouu or cross-bat like tijaff may sound. It's tall, stretched, and mostly ends up choppy. In restlessness, the Alpine crow lets out a kju reminding of jackdaws . In the event of an alarm or a dispute, she falls into a rough ker ker . Alpine crows do not have a courtship or territory song in the true sense. Occasionally, however, they let out a soft sub- song that strings together set pieces from other calls, warbling and chattering.

distribution

Pyrrhocorax fossils can already be found in the late Pliocene of Europe, the Alpine crow can be detected for the first time at the Plio- Pleistocene border ( Villafranchium , about 2.6 mya ) for today's Hungary and Spain. Like the Alpine chough, it was a typical representative of the Ice Age fauna and inhabited large parts of the mammoth steppes that were predominant at the time, from Gibraltar to what is now Hesse and the Czech Republic . With the advance of the forests in the Holocene , the Chough largely disappeared from the temperate latitudes. In isolated cases, human grazing counteracted this development by creating and maintaining open areas and providing the birds with a food base in the form of dry grass . Early natural history works indicate that the Alpine crow lived in a much larger European area in the early 16th century than it does today. For example, it was mentioned by Valerius Cordus as a resident of the Danube rocks near Kelheim and Passau . With the intensification of agriculture and the decline of the sheep pasture economy from the 19th century, the Alpine crow disappeared in many places from their traditional European breeding grounds. Human persecution contributed to this development. The species disappeared in large parts of the Alps, the British Isles and from all the Canary Islands except La Palma . In contrast to this, the species remained largely unmolested in Asia and is not pursued to this day, and grazing is still widespread there. Accordingly, the Asian species range of the Chough is larger and more closed than the European one.

The current range of the Chough is divided into three parts: a large Asian area, a large number of fragmented and small-scale breeding areas in Europe and North Africa and four small breeding populations in the Ethiopian highlands . In Asia, the distribution ranges from the Yellow Sea to northwest China, southeast Siberia and Mongolia to the Mongolian and Tibetan plateau . From there, the Artareal follows the great mountain ranges of South Asia, the Himalayas , the Hindu Kush , the Elburs and the Zāgros Mountains westward to the Caucasus and Anatolia . The great dry steppes and deserts are avoided by the alpine crow. In Turkey , it is mainly found along the southern mountain ranges. To the west of it are some small-scale occurrences in the Aegean Sea and the Balkans . While the Chough is still breeding in large parts of the Apennines and in northern Sicily , it has disappeared from the Eastern Alps for decades. It only occurs in the west of the mountain range. There are dispersed but largely stable populations along the European Atlantic coasts in Ireland , Great Britain and France . The Chough is more or less extensive only in the Pyrenees and on the Iberian Peninsula . Beyond the Strait of Gibraltar there are occurrences in the Atlas , a population that is now highly isolated also exists on La Palma. The occurrences in the northern and southern highlands of Abyssinia are separated from the other populations by the Sahara and the Arabian deserts. Alpine crows are resident birds and have only weak migration tendencies. In winter, some populations leave the summit regions of mountains and move into the lowlands and valleys. The foraging for food sometimes prompts the animals to migrate, but they rarely cover more than ten kilometers.

habitat

The Chough inhabits two different habitat types: on the one hand extensive, open pastures with rocks in the vicinity and on the other hand steep cliffs on the European west coasts. Beaches and poor, dry lawns (2–4 cm high) with a high number of insects are important as feeding habitats. In the western part of the continental distribution area these have mainly been sheep pastures since the Holocene, further east the Alpine crow can also be found on horse and yak pastures . Aside from pasture farming, wind, hillside location or solar radiation can help create suitable foraging habitats for the species. Drinking water in the habitat is obviously also important. Where there are no breeding opportunities in rocks, the Chough also takes nesting sites in buildings. These can be ruins, modern concrete buildings or even inhabited houses, as long as the nest and its immediate surroundings remain undisturbed. In Central Asia the birds can often be found near or in villages, in western China and Mongolia they are year-round residents of cities in many places. There mostly inner-city grass areas function as feeding grounds.

The continental habitats of the Chough are mostly between 2000 and 3000 m above sea level. Occasionally - for example in Andalusia - the species also uses deeper habitats, but is usually more common in higher altitudes. Where the landscape allows it, it often rises even further. It can be found in the Himalayas in summer up to 6000 m, on Mount Everest individuals have been spotted at 7950 m altitude.

Way of life

nutrition

Alpine crows, like most corvids, are omnivores , but mainly feed on insects and other invertebrates. The stomach of the species is a pronounced soft-eater stomach, which is designed to digest soft, liquid-rich pieces of food. The food spectrum is supplemented primarily by seeds, berries and other fruits. Depending on the habitat and season, different groups of invertebrates can become the most important food source. Often ants , beetles or earthworms form the main component of the food. With the decline in insect populations in autumn and winter, grain seeds and berries are increasingly coming to the fore. The spectrum ranges from blackthorn , buckthorn berries and olives on cultivated apples and figs to oats or barley . Grain is apparently preferred, and the Alpine crow is less likely to eat fruit than the Alpine chough. Occasionally the birds also eat small mammals such as shrews , lizards or the eggs of other species, but this is rather the exception. Unlike the Alpine chough and most other species in the family, the Chough usually avoids carrion and human waste.

The Alpine crow prey on arthropods and earthworms primarily by poking into the top soil layer with its long, thin beak. Ants pick the birds from the surface of the earth in very quick succession. When foraging for food, the Chough prefers moist spots in the lawn or rough and bare earth. Sometimes it digs holes up to 20 cm deep in search of food. The birds turn stones and dried pudding to get to the invertebrates underneath. Their beak also enables the Chough to poke for insect larvae in soft droppings without contaminating their plumage. If possible, the food is taken on the ground; only when the situation demands it does she go into the branches of bushes or trees. Often she tries to track down food by shaking it . The hiding of excess food has so far only been observed in birds kept in aviaries. The Chough often drinks, especially after eating sticky or chewy food.

Social and territorial behavior

Alpine crows are sociable birds and live in small flocks for most of the year. Mated individuals usually stay with their partner and join swarms together. Occasionally, flocks can grow large and contain hundreds or thousands of birds. This can happen all year round, but in Europe mostly in September and October when the young birds that have flown out arrive. In the groups, there can be aggressive confrontations, showing off or gatherings called acoustically, but violent attacks with injuries are very rare. Conflicts are usually ended by threatening gestures from the superior animal (upright position of the upper body and beak). Swarms usually spend the night together and go looking for food together. Where the distribution areas overlap, alpine crows are occasionally associated with jackdaws and alpine choughs. There is no competition or argument because the species' diets are very different, and there is usually no competition for nesting sites either. Alpine crows are less common with larger corvids such as carrion crows ( Corvus corone ) or common ravens ( C. corax ). Predators are shared by the swarm of birds hated . The limited and often crowded nesting space occasionally causes the species to breed in small, loose colonies . The breeding pairs defend the immediate nest environment of a few hundred meters against conspecifics, but feeding grounds are not defended.

Reproduction and breeding

Breeding partners are found in the Alpine crow in the non-breeding swarms. The female is courted by the male with a courtship dance, which is followed by feathering. Then it offers the female a choked piece of food. Even after the successful partnering, the male feeds the female regularly when asked to do so by him. Breeding pairs that have survived the second year usually stay together until one partner dies. The first brood is two years old at the earliest, but successful breeders are usually three years old or older. The nest is built by both partners together in late winter and is, if possible, away from the nests of other couples. Covered rock niches and shafts are preferred as nesting sites. The Chough is not a cave breeder in the true sense of the word, the nest entrances are usually wide and open so that the nest can be reached in flight. In addition to rocks, clay slopes, window ledges, roof trusses or chimneys are also used locally for breeding. The prerequisite is that the nesting site is adequately protected, accessible and undisturbed. The nest consists of a misshapen bowl of pencil-thick, interwoven twigs, which is padded in the middle with wool, hair and plant seeds. Nest building takes two to four weeks.

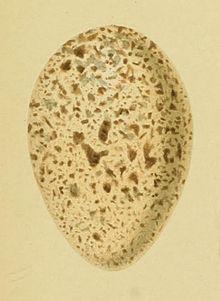

The clutches of the Chough consist of one to seven, usually three to five eggs with a beige to light brown color and dark speckles. The female usually lays them eight to ten days after the nest building is complete. In Eurasia this mostly takes place between mid-April and May. The female incubates the eggs alone while the male provides food. Occasionally conspecifics, probably cubs from previous broods , act as brood helpers . The young hatch after 17-21 days and fledge after 36-41 days. After leaving, they stay with the family for around 50 days before the family joins a larger group of conspecifics. The excursion rate on the British Isles (without complete loss of clutch) is between 42 and 76%; the total losses have a local impact of 32%. In addition to nest robbers, the infestation of the clutches by the jay cuckoo ( Clamator glanduarius ) can also be a cause of the failure of broods.

Diseases and Causes of Mortality

The birds' predators include eagle owls ( Bubo bubo ), peregrine falcons ( Falco peregrinus ) and booted eagles ( Hieraaetus pennatus ). Locally, it is still shot down by humans as a pest or for sports purposes. The plumage of the species included the mite Neotrombicula autumnalis and the jaw lice Bruelia biguttata , Philopterus thryptocephalus , a Menacanthus and Myrsidea species, and Gabucinia delibata . In the latter case, it is controversial whether it is a real parasite or a mutualistic symbiont . Alpine crows with G. delibata in their plumage have, according to field studies, usually a better condition than individuals who lack this featherling . In field studies, the species showed an extremely low susceptibility of 1% to blood parasites of the genera Plasmodium and Babesia . Occasionally, however, the windpipe worm ( Syngamus trachea ) leads to high mortality rates in Chough crow populations.

The mortality rate among birds of a Scottish population was found to be 29% in the first year of life and 26% in the second year of life. The oldest bird to be caught in the wild was a 17 year old male who was still breeding. An unmarked female was believed to have lived in Cornwall for 27 years. Zoo and aviary birds reached an age of 28 and 31 years, but often stopped breeding in the last years of life.

Systematics and taxonomy

The first description of the Chough dates from the 10th edition of Systema Naturae Linnaeus from the year 1758. From Linnaeus introduced because of their elongated, curved beak as " Upopa Pyrrhocorax " to Wiedehopfen , but they arranged in the 12th edition of the genus Corvus to, which at that time still included all corvids . Marmaduke Tunstall finally established the genus Pyrrhocorax for both mountain crows in 1771 and made the Alpine crow their type species through homonymy . The name Pyrrhocorax comes from ancient Greek and means something like "fiery red raven" with reference to the leg and beak color of the species.

The chough can produce hybrids with its sister species , the Alpine chough ( P. graculus ) . Outwardly, these birds are a mixture of both species and have the vocabulary of father and mother. Hybridization can occur both in captivity and in the wild. Most authors nowadays recognize one extinct and eight living subspecies for the Chough, but the differences in behavior and morphology are often only minor. DNA-based phylogenetic analyzes are not available for Alpine choughs and Choughs, or for the individual Chough subspecies. Studies comparing the dimensions and vocalizations of different populations found no differences between the European subspecies, but classified the occurrences from Tian Shan and Ethiopia as basal.

| subspecies | author | Dimensions a | plumage | distribution | annotation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| P. p. baileyi | Rand & Vaurie , 1955 | Wing: ♂ 310–332 mm; Tail: ♂ 145–155 mm; Beak: ♂ 64–70 mm; Tarsus: 59 mm |

Very faint green plumage. | Ethiopia | Named after Alfred Marshall Bailey , collector of the type specimen |

| P. p. barbarous | Vaurie , 1954 | Blades: ♀ 272–281 mm, ♂ 286–310 mm; Tail: ♀ 128–139 mm, ♂ 135–252 mm; Beak: 55–58 mm, ♂ 58–63 mm; Tarsus: ♀ 52–54 mm, ♂ 54–56 mm |

Green sheen on the coat and flight feathers. | North Africa and Canary Islands | " Barbarus " Latin for " Berber " |

| P. p. brachypus | ( Swinhoe , 1871) | Wing: ♂ 304-311 mm; Tail: ♂ 164–166 mm; Beak: ♂ 49–51 mm; Tarsus: ♂ 51–54 mm; Weight: ♀ 238–253 g |

Velvet-black plumage, weak gloss. Wings and tail with a slight purple sheen. | Northeast and East China | " Brachypus " ancient Greek for "short foot" |

| P. p. centralis | Stresemann , 1928 | Wing: ♂ 293–322 mm; Tail: ♂ 151-175 mm; Beak: ♂ 51–58 mm; Tarsus: ♂ 47–52 mm; Weight: ♀ 219–287 g, ♂ 230–290 g |

Bluish shimmer in the plumage. | Kashmir over the Northwest Himalayas over the Altai to Buryatia | |

| P. p. docilis | ( Gmelin , 1774) | Blades: ♀ 284–295 mm, ♂ 299–325 mm; Tail: 141–150 mm, ♂ 140–166 mm; Beak: ♀ 47–54 mm, ♂ 53–59 mm; Tarsus: 51–54 mm, ♂ 55–60 mm; Weight: ♀ 253–300 g, ♂ 314–375 g |

Faint green plumage. | Balkans through Anatolia, Caucasia and Iran to Afghanistan | " Docilis " Latin for "docile", "tame" |

| P. p. erythroramphos | ( Vieillot , 1817) | Blades: ♀ 289–294 mm, ♂ 282–315 mm; Tail: ♀ 137–141 mm, ♂ 135–158 mm; Beak: 48–56 mm, ♂ 55–63 mm; Tarsus: 48–56 mm, ♂ 54–60 mm; Weight: ♀ 293–320 g, ♂ 340–360 g |

Green sheen on tail feathers and wings. | Southern Europe and Continental Western Europe | " Erythror (h) amphos " ancient Greek for "reddish hooked beak " |

| P. p. himalayanus | ( Gould , 1862) | Blades: ♀ 280–332 mm, ♂ 317–336 mm; Tail: ♂ 151-163 mm; Beak: ♂ 59–66 mm; Tarsus: ♂ 59–63 mm; Weight: ♀ 349–385 g, ♂ 450 g |

Strong blue sheen in the plumage. | Southern and central Himalayas to central and southern China | Named after the Himalayas |

| P. p. primigenius † | ( Milne-Edwards , 1875) | Tarsus: ♀♂ 49–53 mm | Europe of the Plio and Pleistocene | Chronosubspecies ; " Primigenius " Latin for "firstborn" | |

| P. p. pyrrhocorax | ( Linnaeus , 1758) | Blades: ♀ 245–293 mm, ♂ 268–293 mm; Tail: tail: 125-140 mm, ♂ 120-141 mm; Beak: 50–53 mm, ♂ 51–59 mm; Tarsus: 48–54 mm, ♂ 49–56 mm; Weight: ♀ 285–325 g, ♂ 335–380 g |

Shine on the back and wing-coverts purple, on wings and tail feathers bluish-green to pale purple. | British Islands | Nominate form |

Inventory and status

Based on European population estimates, BirdLife International assumes 43,000–110,000 breeding pairs in the region, which corresponds to around 129,000–330,000 individuals. For China, 10,000–100,000 breeding pairs are assumed. Based on the European figures, BirdLife estimates the world population at 263,000–1,320,000 birds, but calls for more solid projections. In Europe, the numbers of the Chough were declining at least until the 1980s, since then no clear trends have emerged. The main cause was the loss of suitable breeding and feeding habitats. In contrast to the Alpine chough, the Chough has not been able to adapt to the structural change since the 19th century or even benefit from mountain tourism. The British Isles and the Iberian Peninsula have seen a slight increase in stocks. Unlike most European occurrences, the populations in the Atlas and in Asia Minor , Central and East Asia are large and largely stable. In its Asian area, the Chough is considered to be relatively, locally also very common. According to extrapolations, the four Ethiopian breeding occurrences comprise 1,000–1,300 individuals and, according to studies, can be classified as endangered or endangered.

Extensive protection and resettlement programs have been undertaken in the UK in particular over the past few decades. Nesting aids were built and traditional sheep grazing promoted, which may have contributed to the reintroduction of the species in the south of Great Britain. Switzerland, which is currently still home to around 50 breeding pairs, has classified the Alpine crow as critically endangered on its national red list . The most important factors for the preservation of the European population are the preservation of dry grassland and comparable areas as well as the protection against tourist development and direct persecution.

literature

- Hans-Günther Bauer, Einhard Bezzel and Wolfgang Fiedler : The compendium of birds in Central Europe: Everything about biology, endangerment and protection. Volume 2: Passeriformes - passerine birds. Aula-Verlag, Wiesbaden 2005. ISBN 3-89104-648-0 .

- Guilleromo Blanco, José L. Tella: Protective Association and Breeding Advantages of Choughs Nesting in Lesser Kestrel Colonies. In: Animal Behavior 54, 1997. doi: 10.1006 / anbe.1996.0465 , pp. 335-342.

- Guilleromo Blanco, José L. Tella, Jaime Potti: Feather Mites on Group-living Red-billed Choughs: A Non-parasitic Interaction? In: Journal of Avian Biology 28, 1997. pp. 197-206. ( Full text; PDF; 5.98 MB ( Memento from December 14, 2009 in the Internet Archive )).

- Guillermo Blanco, Santiago Merino, José L. Tella, Juan A. Fargallo, Alvaro Gajón: Hematozoa in two Populations of the Threatened Red-billed Chough in Spain. In: Journal of Wildlife Diseases 33 (3), 1997. pp. 642-645.

- Mark Cocker, Richard Mabey: Birds Britannica. Chatto & Windus, London 2005. ISBN 0-7011-6907-9 .

- Stanley Cramp , Christopher M. Perrins : Handbook of the Birds of Europe, the Middle East, and North Africa. The Birds of the Western Palearctic. Volume VIII: Crows to Finches. Oxford University Press, Hong Kong 1994, ISBN 0-19-854679-3 .

- Anne Delestrade: Distribution and Status of the Ethiopian Population of the Chough Pyrrhocorax pyrrhocorax. In: Bulletin of the British Ornithologist's Club 118 (2), 1998. pp. 101-105.

- Clive Finlayson: Avian Survivors. The History and Biogeography of Palaearctic Birds. T & AD Poyser, London 2011. ISBN 978-0-7136-8865-8 .

- Urs N. Glutz von Blotzheim, KM Bauer : Handbook of the birds of Central Europe. Volume 13 / III: Passeriformes (4th part). AULA-Verlag, Wiesbaden 1993, ISBN 3-89104-460-7 .

- Johann Friedrich Gmelin: Journey through Russia to investigate the three natural kingdoms. Third part. Academy of Sciences, St. Petersburg 1774. ( books.google.de full text).

- John Edward Gray: Mr. Gould on Some New Birds. In: Proceedings of the Scientific Meetings of the Zoological Society of London (1), 1862. pp. 124-125. ( biodiversitylibrary.org full text).

- Josep del Hoyo , Andrew Elliott, Jordi Sargatal, José Cabot: Handbook of the Birds of the World. Volume 14: Bush-shrikes to Old World Sparrows . Lynx Edicions, Barcelona 2009, ISBN 978-84-96553-50-7 .

- Paola Laiolo, Antonio Rolando, Anne Delestrade, Augusto De Sanctis: Vocalizations and Morphology: Interpreting the Divergence among Populations of Chough Pyrrhocorax pyrrhocorax and Alpine Chough P. graculus. In: Bird Study 51, 2004. doi: 10.1080 / 00063650409461360 , pp. 248-255.

- Carl von Linné: Systema naturæ per regna tria naturæ, secundum classes, ordines, genera, species, cum characteribus, differentiis, synonymis, locis. Lars Salvi, Stockholm 1758 ( reader.digitale-sammlungen.de full text).

- Steve Madge , Hilary Burn: Crows & Jays. Princeton University Press, Princeton 1994, ISBN 0-691-08883-7 .

- Rodolphe Meyer de Schauensee: The Birds of China. Smithsonian Institute Press, Washington DC 1984. ISBN 0-87474-362-1 .

- Alphonse Milne-Edwards: Observations on the Birds whose Bones Have Been Found in the Caves of the South-West of France. In: Alphonse Milne-Edwards, Édouard Lartet, Henry Christy: Reliquiae aquitanicae: Being Contributions to the Archeology and Palaeontology of Pèrigord and the Adjoining Provinces of Southern France. Williams, London 1875. pp. 226-247. ( archive.org full text).

- Richard M. Mitchell, James A. Dick: Ectoparasites from Nepal Birds. In: Journal of the Bombay Natural History Society 74, 1975. pp. 264-274. ( phthiraptera.info full text; PDF; 454 kB).

- Cécile Mourer-Chauviré: Les oiseaux du Pléistocène moyen et supérieur de France. Première part. In: Documents des Laboratoires de Géologie de la Faculté des Sciences de Lyon 64 (1), 1975. pp. 1-264.

- Austin Loomer Rand, Charles Vaurie: A New Chough from the Highlands of Abyssinia. In: Bulletin of the British Ornithologists' Club 75, 1955. p. 28.

- Antonio Rolando, Riccardo Caldoni, Augusto De Sanctis, Paola Laiolo: Vigilance and Neighbor Distance in Foraging Flocks of Red-billed Choughs, Pyrrhocorax pyrrhocorax. In: Journal of Zoology 253, 2001. doi: 10.1017 / S095283690100019x , pp. 225-232.

- Erwin Stresemann: The birds of the Elburs expedition 1927. Systematic part: The breeding birds of the area. In: Journal für Ornithologie 76 (29), 1928. doi: 10.1007 / bf01940685 , pp. 326-411.

- Robert Swinhoe: A Revised Catalog of the Birds of China and its Islands, with Descriptions of New Species, References to former Notes, and occasional Remarks. In: Proceedings of the Zoological Society of London , 1871. pp. 337-423. ( biodiversitylibrary.org full text).

- Marmaduke Tunstall: Ornithologia Britannica: seu Avium omnium Britannicarum tam Terrestrium, quam Aquaticarum Catalogus. Sermons Latino, Anglico et Gallico redditus. London, 1771. doi: 10.5962 / bhl.title.14122 . ( biodiversitylibrary.org full text).

- Charles Vaurie: Systematic Notes on Palearctic Birds. No. 4. The Choughs (Pyrrhocorax). In: American Museum Novitates 1648, 1954. pp. 1-7. ( digitallibrary.amnh.org full text; PDF; 663 kB).

- Louis Pierre Vieillot: Nouveau dictionnaire d'histoire naturelle, appliquée aux arts, à l'agriculture, à l'économie rurale et domestique, à la médecine, etc. Tome 8. Deterville, Paris 1817. ( biodiversitylibrary.org full text).

Web links

- S. Butchart, J. Ekstrom: Red-billed Chough Pyrrhocorax pyrrhocorax. BirdLife International, birdlife.org, 2012.

- Feathers of the Chough

Individual evidence

- ↑ a b by Linné 1758, p. 118.

- ↑ Cramp & Perrins 1994, pp. 118-119.

- ↑ Madge & Burn 1994, p. 133.

- ↑ Glutz von Blotzheim & Bauer 1993, pp. 1620–1621.

- ↑ Cocker & Mabey 2005, pp. 406-408.

- ↑ Glutz von Blotzheim & Bauer 1993, pp. 1642–1643.

- ↑ Glutz von Blotzheim & Bauer 1993, pp. 1623-1624.

- ↑ Finlayson 2011, p. 268.

- ↑ Glutz von Blotzheim & Bauer 1993, pp. 1629-1632.

- ↑ Meyer de Schauensee 1984, p. 458.

- ↑ a b Butchart & Ekstrom 2012. Retrieved September 17, 2012.

- ↑ Delestrade 1998, p. 101.

- ↑ Cramp & Perrins 1994, p. 108.

- ↑ a b c Madge & Burn 1994, p. 134.

- ↑ Glutz von Blotzheim & Bauer 1993, p. 1636.

- ↑ Glutz von Blotzheim & Bauer 1993, pp. 1649-1650.

- ↑ Glutz von Blotzheim & Bauer 1993, pp. 1644-1645.

- ↑ Glutz von Blotzheim & Bauer 1993, pp. 1645-1646.

- ↑ Glutz von Blotzheim & Bauer 1993, pp. 1638-1640.

- ↑ Glutz von Blotzheim & Bauer 1993, pp. 1640–1641.

- ↑ a b c del Hoyo et al. 2009, p. 616.

- ↑ a b Glutz von Blotzheim & Bauer 1993, p. 1641.

- ↑ Rolando et al. 2001, p. 226.

- ↑ Blanco & Tella 1997, p. 338.

- ↑ Blanco et al. 1997b, p. 644.

- ↑ Mitchell & Dick 1975, p. 271.

- ↑ Blanco et al. 1997a, p. 202.

- ↑ Blanco et al. 1997b, p. 643.

- ↑ Glutz von Blotzheim & Bauer 1993, pp. 1641–1642.

- ↑ Tunstall 1771, p. 2.

- ↑ Glutz von Blotzheim & Bauer 1993, p. 1571.

- ↑ Laiolo et al. 2004, pp. 252-253.

- ↑ Rand & Vaurie 1955, p. 28.

- ↑ Vaurie 1954, p. 1.

- ↑ Swinhoe 1871, p. 383.

- ↑ Stresemann 1928, p. 344.

- ↑ Gmelin 1774, p. 365.

- ↑ Vieillot 1817, p. 2.

- ↑ Gray 1862, p. 125.

- ↑ Milne-Edwards 1875, p. 235.

- ↑ Mourer-Chauviré 1975, p. 221.

- ↑ Bauer et al. 2005, p. 52.

- ↑ Cramp & Perrins 1994, pp. 105-120.

- ↑ Delestrade 1998, p. 104.

- ↑ Bauer et al. 2005, p. 54.