Jay cuckoo

| Jay cuckoo | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Common Blue Cuckoo ( Clamator glandarius ) |

||||||||||

| Systematics | ||||||||||

|

||||||||||

| Scientific name | ||||||||||

| Clamator glandarius | ||||||||||

| ( Linnaeus , 1758) |

The jay cuckoo ( Clamator glandarius ) is a cuckoo bird that occurs from the Mediterranean region to southern Africa.

The Great Spotted Cuckoo is a brood parasite , which his boys most of corvids can raise. Unlike in Central Europe occurring cuckoo hatch at the Great Spotted Cuckoo also young birds of the host bird, albeit a smaller number than in non-parasitized by the Great Spotted Cuckoo nests. Due to the greater assertiveness of the nestling of the jay cuckoo, the host bird cubs lag behind in growth and some of them starve to death.

The most important host species in Europe are magpie and carrion crow .

features

With a body length of 35 to 39 centimeters, a weight of 140 to 170 g and a wingspan of 58 to 66 cm, the jay cuckoo is slightly larger than the cuckoo . Its tail is slightly longer and narrower and the wings wider and more blunt than those of the cuckoo. The legs are gray. Young and adult birds have a bright orange-red eye ring. The beak is gray at the base, otherwise black. The back and wings are dark gray, the umbrella feathers and small and large blankets have white spots on the tips. The arm and hand wings have white hems at the tips, as do the tail feathers, which are graduated in length. The underside is light, the throat and chest are yellowish in color. The adult jay cuckoos have a striking, silver-gray hood , crown and ear-coverts. There is no difference between the sexes.

Newly hatched cuckoos are nestled and initially naked. The skin is pink flesh-colored. The throat is red, the palate and the base of the tongue are covered with thorn-like papillae. The legs and toes are pink. The eyes of the young jay cuckoo open after five to eight days. With about 14 days they can sit on the nesting beach and between the 16th and 21st day of life they are able to fly. Fledglings have black tops, heads and wings. The wings of the hand are reddish brown. After the first moult, these black parts of the plumage and the wings are sepia-colored.

The jay cuckoo moves on the ground mostly hopping forward with its tail raised. Sitting on a fence, his posture is reminiscent of a magpie. The flight is cuckoo-like with sometimes very flat, rapid wing beats and short glide paths. During the breeding season, cuckoos are mostly seen in pairs.

voice

The jay cuckoo is vocal and loud. The calls are very diverse. He often calls out loudly rattling "tjerr-tjerr-tje-tje-tje" or "ki-ki-ki-kriä-kriä-kriä ...", which can sometimes be reminiscent of the wheatear . The female in particular has rows of calls that, with their rolling, cackling gi-gi-gi-gi-gi-kü-kü-kü, are more reminiscent of the calls of green woodpeckers . When aroused, he calls out "chäh" nasally and roughly. The song of the jay cuckoo, on the other hand, is seldom heard. It consists of a stanza of monotonously lined up klü-u , üüg-üüg , ki-ü or kliiok elements that fall in pitch .

distribution and habitat

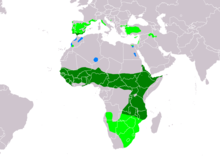

The distribution area includes southwest and southern Europe , Asia Minor up to western Iran and up to Upper Egypt and parts of Africa south of the Sahara . Over the past 50 years it has expanded its range in southern Europe somewhat and has become more common in Spain, France and Italy. In Central Europe he is a seldom proven errant .

The populations living far north or south of their range usually migrate from Europe to Africa and from South Africa northwards. When migrating, the birds form large flocks.

The habitat is the flat or hilly, open area with individual bushes and trees. Occasionally he also follows his host birds in park areas. In Europe, it is mainly found in semi-arid regions.

behavior

The jay cuckoo is an insect eater and looks for food mainly on the ground in light forest regions. Like other cuckoos, it also eats large, hairy caterpillars, which it sometimes frees from the hair before consumption, which is not possible for many other bird species. Small reptiles complete the menu.

Reproduction

The jay cuckoo is a breeding parasite and it lays its eggs in the nests of corvids , especially magpies , carrion crows , tortoiseshell and blue star . In Africa include starlings to the hosts. The male distracts the host bird parents while the female lays an egg in the nest. In a breeding season, the female can lay up to 18 eggs two days apart.

Revier and courtship

In some regions of their distribution area, jay cuckoos occupy breeding grounds. This is documented, among other things, for the south of Spain, where the districts cover between 1 and 3.7 square kilometers. Up to 40 magpies' nests, the most important European host bird species, were located in these areas. However, territories often overlap with that of other jays and cuckoos, and where there are a large number of jays, territorial behavior rarely occurs.

During the entire egg-laying phase, the male woos the female by bringing her large caterpillars or other insects. The offering of food is usually followed by copulation.

Egg laying

The female looks for suitable nests for egg-laying by observing the host birds, often from a hidden stand guard. Once it has found a suitable nest, both parent birds often cooperate to enable the female to lay eggs in the foreign nest. The male then sits in a conspicuous place near the nest and attracts the attention of the host birds by calling out loudly. The female, on the other hand, remains silent and approaches the nest using cover. As soon as the host birds fly in the direction of the male, the female goes to the nest and lays her egg there. The eggs are laid at an extraordinary speed. Although most magpies' nests have a hood-like superstructure made up of bulky twigs, it has left the nest again within 10 seconds. This speed is crucial: if magpies were to surprise it while the female cuckoo was in the nest, they would attack the female and, with a high probability, injure it. With open nests such as crow's nests, the female is even faster. Here it leaves the nest after three seconds: Most crows are larger than magpies, injuries from them would be more serious.

Unlike the cuckoo, the female cuckoo does not remove an egg from the host bird's nest. This is presumably due to the fact that this lengthens the female's stay in the host bird's nest. In addition, since the common jay chuckles occasionally visit their host bird's nest more than once, there is a risk that a common blue jellyfish will remove it. However, since parasitized nests of magpies are more likely to have damaged eggs, it is possible that the female cuckoo chicken pecks at the eggs lying there during the short time in the nest or that the eggs are damaged during egg-laying. The risk of cuckoo eggs being damaged by picking or laying eggs quickly is lower than with magpies eggs. Jay cuckoo eggs have a thicker and more robust shell. On average, one or two magpie nestlings hatch in parasitized magpies' nests, while there are on average five in non-parasitized nests.

Genetic analyzes have shown that a female Common Cuckoo uses different host bird species during a breeding season. In investigations in Spain, female jay cuckoos used the nests of carrion crows at the beginning and the end of their breeding season and those of magpies during the main season. Magpies are the preferred host birds, but the female jay cuckoo switches to other species when there are not enough magpies' nests available.

Eggs

The eggs of the jay cuckoo are elliptical to spindle-shaped and taper slightly towards the poles. They are pale greenish-blue and densely covered with light brown and gray dots and spots. Although the eggs of different female cuckoos may differ slightly, there is a lack of adaptability in the egg color, as occurs, for example, in the cuckoo. While females of this species have specialized in a host bird and lay eggs that almost correspond in color and pattern to these, the Common Cuckoo pursues a different strategy. Its eggs are generally similar to many of its host bird species. In Europe the eggs correspond to those of the magpie and are also similar in size. They also correspond in color to those of the carrion crows, but are only half the size of their eggs.

In Africa the tortoiseshell is the most common host bird and here, too, the coloration corresponds to its eggs, but again the eggs of the crowbird are significantly larger. In contrast, the eggs of the Cape crow ( Corvus capensis ), which is one of the most common host bird species in South Africa, are more reddish.

Degree of parasitization

The degree of parasitization has not been investigated in the entire distribution area of the jay cuckoo. However, the degree of parasitism in South Africa is 13 percent in shield ravens, 10 percent in cape crows and 5 percent in two-colored starlings .

In the south of Spain, over a ten-year study period, a degree of parasitism of 43 percent in magpies and 8 percent in carrion crows was found. The eggs of the jay cuckoo are also found in two percent of the nests of jackdaws and 5 percent of the nests of Alpine crows .

The young birds grow up

In contrast to the cuckoo, the chick of this species tolerates the offspring of its adoptive parents next to it. Nevertheless, the reproduction rate of magpies in nests parasitized by jay cuckoos is low and, according to individual studies, averages only 0.6 fledgling young birds, while in non-parasitized nests an average of 3.5 magpies fly out. The difference is partly due to the damage to the magpie eggs by the laying jay cuckoo female, but also due to the behavior of the cuckoo cubs in the nest. Although magpie cubs are larger (175 grams at the time they fledge) than jay cuckoo nests (135 grams), jay cuckoos prevail over their nesting competitors. They succeed in this because they hatch a few days before the magpie cubs and thus have a small growth advantage. They also grow significantly faster than the magpie cubs and are fledged after 15 to 16 days, while magpie nestlings only do so after 21 to 27 days. Crow nests even take 30 to 40 days to be able to leave the nest.

Magpies nestlings that hatch three or four days after the jay cuckoo have very little chance of fledging. Not only are the jay cuckoo nestlings able to reach out more towards the food-bringing magpies, but the stronger nestlings also step on their nest siblings and spread their wings over them, so that they have a significantly lower chance of getting food. Occasionally they also show aggressive behavior and peck at the heads of fellow nestlings. If there are two cuckoo nests in the nest, this behavior also makes it more likely that the older of the two will fledge alone.

Jay cuckoo nestlings not only imitate the begging calls of their host birds, but also show a more pronounced begging behavior than the magpie nestlings and are therefore more fed by the host birds. Unlike magpies nestlings, they beg again for food with loud calls half an hour after feeding. Experiments have shown that they often spit out the food they have eaten, but continue to beg. This exaggerated begging behavior enables them to assert themselves more strongly in the nest. NB Davies points out that this highly exaggerated begging behavior may also be an adaptation, since the jay cuckoo nestlings differ from the offspring of their host birds with increasing days of life. The difference is greater than that of many other parasites, and the behavior of the jay cuckoo may compensate for this. Experiments have shown that magpies at least have a habituation effect to the different-looking nestling: while an added jay cuckoo nestling in a magpie nest that has not yet been parasitized is attacked by the parent birds, this aggressive behavior does not occur when another jay cuckoo nestling is growing in the nest.

Possible further behavioral adaptations to the brood parasitism

The Israeli zoologist Amotz Zahavi set up the so-called "Mafia hypothesis" in 1979, according to which intelligent birds like crows, which are even able to distinguish individual people from one another, accept an alien egg and hatch in their nest and raise the nestling, because if the egg is removed they run the risk of losing all of their brood. According to this hypothesis, they raise fewer young birds than if their nest were not parasitized, but they have a chance of at least little breeding success.

The jay cuckoo is the only species on which this hypothesis has been tested so far. In the region around Guadix in the Spanish province of Granada, the degree of parasitism in magpies was 10 percent before the start of the study in 1990. It was noticeable that in most cases where a cuckoo egg was laid in a magpie nest, young birds also fledged from this nest. In the few cases where the alien egg was removed by magpies, the clutch was very often destroyed. In the period up to 1992 this was intensified experimentally. Scientists deliberately removed cuckoo eggs from individual nests; the control group were parent nests, which were parasitized, but from which no egg was removed. It was found that in more than half of the nests from which the jay cuckoo egg was removed, nest robberies subsequently occurred and either eggs or even young birds disappeared. In contrast, this was only the case in 10 percent of the control group.

Two pieces of evidence indicate that this was not caused by predators: occasionally injured nestlings were left behind in the nest and in one case a female cuckoo hen equipped with a transmitter returned to the nest it had parasitized and pecked after its egg had been removed there , the remaining eggs. NB Davies points out that this is a remarkable achievement by the cuckoos: they would not only be able to distinguish their eggs from those of the magpie despite the similar coloration, but could also determine whether their own egg was missing. NB Davies also points out that this behavior makes sense from the jay cuckoo's point of view: A destroyed clutch increases the chance that the host birds will make a second attempt at breeding; the cuckoo then has another chance to parasitize the nest.

The question of whether the host birds remove the alien egg less frequently in a second clutch was tested in a second study in 1996/1997. Here, the scientists placed artificial cuckoo eggs in the nests. In the case of the magpies that removed this egg, the eggs in the nest were destroyed in the same way as a jay cuckoo would. In the second clutch that followed, an artificial cuckoo egg was placed in the nest again. Half of the pairs of magpies now changed their behavior and accepted the foreign egg in this second attempt. This behavior was particularly pronounced where jay cuckoos were common. The “Mafia hypothesis” put forward by Amotz Zahav could not be fully confirmed. From the point of view of reproductive success, it would make more sense for magpies to remove a cuckoo egg and risk that the clutch would be destroyed.

supporting documents

literature

- Heiner-Heiner Bergmann, Siegfried Klaus, Franz Müller, Wolfgang Scherzinger, Jon E. Swenson, Jochen Wiesner: The hazel grouse. (= Die Neue Brehm-Bücherei. Volume 77). Westarp Sciences, Magdeburg 1996, ISBN 3-89432-499-6 .

- NB Davies: Cuckoos, Cowbirds and Other Cheats. T & AD Poyser, London 2000, ISBN 0-85661-135-2 .

- Johannes Erhitzøe, Clive F. Mann, Frederik P. Brammer, Richard A. Fuller: Cuckoos of the World. Christopher Helm, London 2012, ISBN 978-0-7136-6034-0 .

- Dieter Glandt: Kolkrabe & Co. AULA-Verlag, Wiebelsheim; 2012. ISBN 978-3-89104-760-6 , pp. 66-67

, * Colin Harrison, Alan Greensmith: Birds. Dorling Kindersly Limited, London 1993,2000, ISBN 3-8310-0785-3 .

- Bryan Richard: Birds. Parragon, Bath, ISBN 1-4054-5506-3 .

- Svensson, L .; Grant, PJ; Mullarney, K .; Zetterström, D .: The new cosmos bird guide - all species of Europe, North Africa and the Middle East. Franckh-Kosmos Verlags-GmbH & Co., Stuttgart 1999. ISBN 3-440-07720-9 .

Web links

- Jaw cuckoo on natur-lexikon.com including photos

- Clamator glandarius in the endangered Red List species the IUCN 2008. Posted by: BirdLife International, 2008. Accessed January 14 of 2009.

- Videos, photos and sound recordings for Clamator glandarius in the Internet Bird Collection

- Age and gender characteristics (PDF; 1.7 MB) by J. Blasco-Zumeta and G.-M. Heinze (Eng.)

- Feathers of the jay cuckoo

Single receipts

- ↑ a b Davies: Cuckoos, Cowbirds and Other Cheats. P. 99.

- ↑ Baumann, p. 293

- ↑ Baumann et al., P. 293

- ↑ Baumann, p. 293

- ↑ a b c d e Davies: Cuckoos, Cowbirds and Other Cheats. P. 100.

- ↑ a b Davies: Cuckoos, Cowbirds and Other Cheats. P. 101.

- ↑ a b c Davies: Cuckoos, Cowbirds and Other Cheats. P. 102.

- ↑ a b c Davies: Cuckoos, Cowbirds and Other Cheats. P. 103.

- ↑ a b Davies: Cuckoos, Cowbirds and Other Cheats. P. 104.

- ↑ a b Davies: Cuckoos, Cowbirds and Other Cheats. P. 105.

- ↑ Davies: Cuckoos, Cowbirds and Other Cheats. P. 107.

- ↑ Davies: Cuckoos, Cowbirds and Other Cheats. P. 113.

- ↑ Davies: Cuckoos, Cowbirds and Other Cheats. P. 114.

- ↑ a b c d Davies: Cuckoos, Cowbirds and Other Cheats. P. 115.

- ↑ a b c Davies: Cuckoos, Cowbirds and Other Cheats. P. 116.