Mallard

| Mallard | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Mallard duck, drake above, female below |

||||||||||||

| Systematics | ||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||

| Scientific name | ||||||||||||

| Anas platyrhynchos | ||||||||||||

| Linnaeus , 1758 | ||||||||||||

| Subspecies | ||||||||||||

|

The Mallard ( Anas platyrhynchos ) is a bird art from the family of ducks (Anatidae).

The mallard is the largest and most common swimming duck in Europe and the ancestral form of the domestic duck . Adult males in courtship dress are unmistakable with their green metallic head, yellow beak and white neck ring, the females are inconspicuous, light brown with an orange beak.

Mallards are found in most of Eurasia , the far north of Africa and large parts of North America , and have been introduced as breeding birds in New Zealand and Australia . Their frequency is due to the fact that they are not very demanding in the choice of their breeding sites as well as their whereabouts , provided that some type of water is present.

Naming

The current term mallard did not establish itself as the usual German term until the 20th century; in older literature it is also referred to as March duck . The name "March duck", which is no longer in use, refers to the row and breeding season of the mallard. The present name can be understood as a reference to their breeding grounds, including on stick set willow , willow bushes or brushwood piles belong. Mallards do not breed on it very often, but the behavior is so noticeable for a species of duck that the name we use today developed from it.

For a long time the name was Wild Duck common, which is an unsatisfactory term, ornithological because this name across species also applies to all other wild ducks. This term can still be found in the hunter's language , and a mallard is also usually prepared in a wild duck dish in gastronomy .

The scientific species name platyrhynchos means broad-billed and is derived from ancient Greek.

Appearance

Appearance of fully grown mallards

Mallards grow up to 58 centimeters long, their wingspan is up to 95 centimeters. The male wears his simple dress between July and August and looks very similar to the female. The sex can only be determined on the basis of the beak color during this time, because the beak of the male is still clearly yellow, partly with a tinge of green, whereas the beak of the female looks orange in the basic color and partly completely, partly only dark gray in the middle until brown overflows. The female has a brown-gray speckled color, which means that the animals are well camouflaged on land. The only noticeable thing is the blue wing mirror, which corresponds to that of the male. In flight, the white border of the blue wing mirror is visible in both sexes.

Mallards have around 10,000 down and feather feathers that protect them from moisture and cold. They always grease this plumage so that no water penetrates through the plumage. The oil gland at the base of the tail supplies the fat . The duck picks up the fat with its beak and uses it to brush it onto the plumage. On the water, the duck is carried by an air cushion. The air is held between the down plumage and the cover feathers seal off the down. Together with the fat pad under the skin, the trapped air layer prevents body heat from being lost and the duck from cooling down.

Magnificent dress of drakes

The elephant's magnificent dress is gray with a brown chest, brownish back and black upper and lower tail-coverts. The head is metallic green with a white neck ring underneath, the beak green-yellow. At the rear edge of the wing there is a metallic blue, white lined band, the wing mirror . The black feathers on the tip of the tail are rolled up into drake curls.

Mauser

When Mauser course , there is considerable individual as well as population-specific differences. In Central European mallards, the drakes change their wing plumage between July and August at the beginning of the preenuptial moult and are then unable to fly for three to five weeks. Meanwhile, the rest of the plumage changes. The subsequent development of the magnificent dress will not be completed until December. The postnuptial moulting of mallard pelas begins in mid-May with the shedding of the middle control feathers while the females are still breeding. The moulting of the small plumage then follows. In females, the moulting takes place in September and the change of small plumage in breeding plumage between October and November.

Appearance of hybridized mallards

Mallards generally tend to hybridize with other duck species and like to cross with the domestic ducks descended from them . Conversely, mallards from wild populations are repeatedly used to freshen the domestic ducks' blood or are used to breed new lofts.

Individuals that differ in their appearance from the normal mallard can occasionally also be observed in the field. More often, however, such miscolored individuals appear among urban populations. This is likely to be due to the fact that captive refugees, i.e. both escaped domestic ducks and non-native aquatic fowl, settle in the same urban areas as the mallards due to their shorter flight distance from humans and the more abundant food supply.

Often dark, often almost pure black, brown or dark green individuals can be observed. Often a white "bib" appears on the chest, which may be due to the hybridization with white domestic ducks. Individuals with whitish lightened areas are rarer. In some males the feather feathers of the wings are more or less darkened or the white neck ring is widened. In Hamburg, 13 percent of mallards are incorrectly colored in the city center, but only 0.7 percent on the outskirts.

In order to reduce the further hybridization of the species, the incorrectly colored individuals are shot down preferentially.

Appearance of the downy chicks and fledglings

The downy chicks of the mallard are brown on the upper side of the body and yellow-brown on the underside. A dark line of color runs from the base of the beak over the eye to the neck. At the back of the head, at the level of the ears, there is a small dark spot of color, and a number of mallard chicks have another dark spot of color at the base of the beak. The sides of the head and the fore neck are yellow-brown. Yellow areas of color can also be found on the wings, the back and the flanks.

At the time of hatching, the downy chicks have a dark gray upper beak with a light brown nail. The edges of the beak are occasionally pink-brown in color. The lower bill is brownish pink. The legs and feet are dark gray, with the sides of the legs slightly yellowish. The webbed feet are dark. By the time young mallards fled, the upper bill is pale blue-gray, the legs and feet are yellow-orange with dark webbed feet.

The youth dress largely corresponds to the simple dress of the female. In young ducks, however, the belly-side contour feathers are darker in color than those of the female resting dress. The sexes differ by the white color at the tips of the large elytra. In females this extends up to the fifteenth, in males, however, only up to the twelfth.

Vocalizations

voice

The mallard is a duck with a lot of reputation. Males and females have different calls. A muffled "räb" is characteristic of the drake, which they occasionally let hear in a row as "rääb-räb-räb-räb" with a falling pitch and volume. The females have a similar series of calls, which sound more like “wak wak wak” or “wäk wäk wäk”.

The mallard's sound repertoire also includes some instrumental sounds . This includes the dull ringing "wich wich wich ...", which is characteristic of the flight and is generated with the wings.

Courtship sounds

A series of calls are associated with courtship. This includes the characteristic grunting whistle of the male, which is onomatopoeically described as "gerijib" or "fihb". It sounds particularly often when the drakes dip their beaks during courtship and then pull up their head and body.

During courtship, the males also perform ritualized sham cleaning, in which they touch the quills of the wings of the hand with their beak from behind. This creates a rattling “rrp” sound.

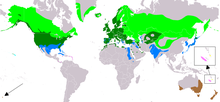

distribution

Global distribution

The mallard is found all over the northern hemisphere, from Europe to Asia to North America . In North America it is only absent in the extreme north in the areas of the tundra from Canada to Maine and eastwards to Nova Scotia. It has its North American distribution focus in the so-called Prairie Pothole region of North and South Dakota , Manitoba and Saskatchewan . In Europe it is only absent in higher mountain areas. In the Alps it is still common in more open valleys up to altitudes of 1000 meters, the highest nesting sites were registered at around 2000 meters. In Asia, the mallard avoids the coldest tundra and occurs as far as the east of the Himalayas. As a breeding bird, it is limited to the Holarctic . It only reaches the oriental region for wintering. For example, it winters in the plains of northern India and southern China.

In Australia and New Zealand , the Mallard has been introduced. It occurs wherever the climate corresponds to that of the distribution area in the northern hemisphere. It was introduced in Australia in 1862 at the earliest and has spread across the Australian continent especially since the 1950s. Due to its climatic demands, it is comparatively rare on this continent and occurs predominantly in Tasmania , in the southeast and in a small area in southwest Australia. Here it mainly uses urban areas or very heavily agrarian landscapes and is only rarely observed in regions that are not densely populated by humans. In New Zealand, the mallard was introduced in large numbers from 1867. Between 1896 and 1918, mallards were released into the wild, mainly on the North Island. There were attempts to introduce it in the South Island in the 1920s, but these were largely unsuccessful. In the 1950s, the mallard began to spread very strongly, which led to a settlement on the South Island. As early as 1981, the New Zealand population was estimated to be more than five million individuals. Mallards can also be found today on Stewart Island and other, smaller islands off the New Zealand coast. The introduction of the mallard into New Zealand is now classified as problematic. Among other bastardiert the wild duck with the native Pacific Black Duck . The first hybrids between mallards and eyebrow ducks were reported as early as 1917, and it is now assumed that mallards are crossed in all eyebrow duck populations. Even in the third generation, hybrids are no longer recognizable by their plumage.

Preferred habitats

The mallard is very adaptable and can be found almost anywhere there is water. Mallards swim on lakes , in ponds , inland waterways , mountain lakes and also stay in small forest and meadow ditches.

Cultural followers in cities

Similar to the blackbird , a process of urbanization is taking place which, according to a report by Johann Friedrich Naumann, began as early as the 18th century. City ducks inhabit bodies of water in the area of cities, especially ponds and ponds in parks, but also rivers that flow through the cities and other natural bodies of water such as lakes in the area of cities. The mallard even populates larger wells . Mallards are predestined for urbanization due to their undemanding choice of nesting place and their omnivorous way of life. In urban areas, mallards choose nest locations that often look unusual from a human perspective. These include nests on balconies, on the flat roofs of high-rise buildings and in sheds or stables.

In some places, mallards compete with Egyptian geese , which have been introduced for some time and are generally inferior to them in defending breeding grounds.

Natural enemies

The natural enemies of the mallard are foxes , raccoons and birds of prey ; Brown rats and martens particularly target the duck eggs. Since the females are more likely to fall prey to predators during the breeding season, there are more drakes than ducks in many populations. In the wild, ducks can live to be 10 to 15 years old. However, they can live to be 40 years old under human care.

nutrition

The mallard is undemanding in terms of the preferred food, it is a decidedly omnivorous species that eats everything it can adequately digest and obtain without great effort. New food sources are quickly recognized by this species and used immediately.

The food of the mallard mainly consists of vegetable matter. It uses seeds , fruits , aquatic, bank and land plants. The food spectrum also includes molluscs , larvae , small crabs , tadpoles , spawn, small fish , frogs , worms and snails .

The food composition is subject to seasonal fluctuations. Central European mallards live almost exclusively on vegetable food at the beginning and during the breeding season. First seeds and wintering green parts and later the freshly sprouting green are preferred to eat. At the point in time at which the chicks hatch, they not only find abundant vegetable food, but also abundant animal food in the form of insects and their larvae. Mallard chicks do not specialize in a particular food and find adequate food options in Central Europe as early as the beginning of May. In experiments, however, the influence of animal protein on the development of the young could be demonstrated. Young mallards, which find a lot of animal protein, have a significantly higher growth rate than those who are mainly plant-based.

As soon as the young have fledged, mallards increasingly look for food in the fields. The not yet ripe grains are particularly popular with cereals. In autumn, mallards also eat acorns and other nuts . Even potatoes are accepted by it as a food plant. The expansion of its food spectrum to include this plant, which was imported from South America, is relatively well documented for Great Britain. There this eating habit first appeared in the severe winters between 1837 and 1855. This food expansion was favored by the potato rot, which led to many farmers allowing their crops to rot in the field. According to English reports from 1863, mallards preferred potatoes affected by this disease, even cereals.

The mallard occasionally eats bread and kitchen waste at feeding stations. Although it is basically very adaptable in its diet, it does not eat salt-loving plants. Mallards living in Greenland, for example, eat almost exclusively marine molluscs.

Gudgeon

While searching for food under the surface of the water, the mallards dive with their heads, flap their wings on the surface of the water and then tip over. This posture, which is characteristic of mallards, with its rump protruding vertically from the water , is known as “ rooting ”. In doing so, they search the bottom of the water below them for anything edible up to a depth of about half a meter. With their beak they bite off parts of the plant and push the water, which they also absorbed, out through the horn strips of their beak. These parts of the beak act like a sieve in which the food sticks.

Reproduction

Courtship and copulation

The resident birds among the mallards usually mate in autumn, while the migratory birds mostly do not form a pair until spring. Among the migratory birds, it is usually the older females who first visit their breeding area. Most populations also have an overhang of males. This means that mallards are very restless during the mating season and are noticeable due to the frequent row flights.

A special feature of mallard ducks is that they have a spiral-wound penis in their cloaca . It occurs in a number of duck species and, in the phylogenetic sense, represents an analogy to the penis of mammals.

Drake's social ball

Mallard ducks are characterized by an extensive group of drakes, shortly after they put on their magnificent dress in early autumn. This form of courtship has no meaning in the sense of a mating prelude, but contributes to the formation of groups of animals of the same species, which then facilitates pair formation.

Mallard ducks fluff up their belly and side feathers and lift their wings slightly. In this phase they show a typical movement pattern in which the tail feathers are first shaken vigorously when the head feathers are raised, then the head is pulled in deeply and then jerked up strongly. The drake then sinks back down while shaking the tail plumage vigorously again. This is followed by conspicuous, repeatedly repeated movement patterns , which Konrad Lorenz described as grunt whistle, short-up-up and down-up movement.

Couples courtship

After this common breed of drakes, mallards mate loosely for the first time. After the engagement period, which can be observed in addition to the “drinking” and driving away other drakes, especially swimming behind and next to each other, the annual search for partners, the row time, takes place in January to early February. Rowing time is called courtship because several drakes “line up” behind the few females. So-called row flights , in which several males follow one female, are also very common in mallards .

Mallards have an extensive courtship repertoire, but this is often not shown when drakes compete for females. Often, females are mated by several males without the usual courtship ceremony preceding. Numerous cases have been documented of the female being drowned by overzealous males.

The nest

Together, the couples look for a nesting place, which can be on an embankment, but sometimes up to two or three kilometers from the water. Mallards are extremely versatile in their choice of nest location. The attempt to determine the characteristics of the choice has so far only shown that the choice of nesting site adapts to the circumstances of the respective environment. In lowland areas, the nests are mainly found in grassland , on lakes with pronounced vegetation belts in the bank vegetation and on forest lakes in the forest. Mallards mostly build their nests in trees in the floodplain of the Warta in Poland. In forests they breed on tree stumps , but they also accept tree hollows and also breed in old crow , magpie and raptor nests.

The nest itself is a simple, flat hollow that the female presses into the ground and padded with coarse stalks. After the nest-building, when brood begins, the drake leaves the duck - a behavior that can be interpreted as an adaptation to its conspicuous plumage.

Clutches and young birds

The females hatch a clutch of 7 to 16 eggs once a year for 25 to 28 days, from March onwards they lay one egg a day. If the first four eggs left open remain unimpaired by jellyfish, the duck continues to lay in this nest and now covers the eggs when leaving the nest for a short time. The chick starts to beep three days before hatching . With the egg tooth (pointed tooth at the end of the beak) it drills a hole in the lime shell of the egg and kicks itself out of the shell, after which it remains lying exhausted. Ducks flee the nest , which means that they are already very well developed when they hatch, leave the nest after six to twelve hours and can swim from the start. Their instinctive behavior to throw themselves into some unknown hole while fleeing can lead to them ending up in manhole covers, basement shafts, etc., especially in populated areas, where they can no longer get out on their own. In the first hours of their lives they chase after whoever they first see. Usually this is the mother. This form of interaction between learning and innate behavior is called imprinting and is a crucial part of the reproductive cycle of those who flee from the nest.

After eight weeks, the young ducks can fly. About 50 to 60 days remains the duck even with the full-fledged chick in a Schoof , a duck-nest family together.

behavior

Mallards fly up almost vertically. The flight is quick and straight.

Migratory behavior

Mallards show great variability in their migration behavior. The representatives native to Eastern and Northern Europe are mostly migratory birds and migrate to Central, Western or Southwestern Europe from October. In contrast, representatives resident in western and southern Europe usually do not show any migratory behavior, but are resident birds . Representatives resident in Central Europe can stay on site, undertake only shorter hikes or show further south-west hikes. On July 9, 1963, an airliner collided with a mallard over Nevada at an altitude of 6,400 m (21,000 ft). A mallard from Hessen flew 2250 km at up to 125 km / h to a lake 300 km north of Moscow in less than 3 days.

Population and hunting

The mallard is the most common duck species in Europe. The population in Europe is roughly estimated at 3.3 to 5.1 million breeding pairs. Of these, at least 900,000 to 1.7 million breeding pairs are found in Central Europe. The current total population in Germany is between 190,000 and 345,000 breeding pairs. The depletion of the population due to cold winters and regionally decreasing food supply is compensated for by the following mild winters and by a decline in hunting. Overall, the inventory fluctuations are at a very high level. The hunting season for mallards in Germany is determined by the Federal Hunting Act from September 1st to January 15th. The total annual distance has decreased by 30 percent in the last ten years and was 345,000 hunted birds in the 2015/16 hunting year. Bavaria, Lower Saxony and North Rhine-Westphalia accounted for a total of 68 percent of this. In Switzerland, the number of mallards shot down was 5,700 in 2015 and around 50,000 individuals in Austria.

Varia

In Weimar there is a mallard fountain that the Weimar sculptor Arno Zauche created around 1910.

literature

- Gerhard Aubrecht, Günter Holzer: Mallards . Biology, ecology, behavior. Österreichischer Agrarverlag, Leopoldsdorf 2000, ISBN 3-7040-1500-8 .

- Hans-Günther Bauer, Einhard Bezzel and Wolfgang Fiedler (eds.): The compendium of birds in Central Europe: Everything about biology, endangerment and protection. Volume 1: Nonpasseriformes - non-sparrow birds. Aula-Verlag Wiebelsheim, Wiesbaden 2005, ISBN 3-89104-647-2 .

- Uwe Gille: A contribution to the quantitative anatomy of birds with special consideration of the Anatidae. Habilitation thesis University of Leipzig , 1997.

- PJ Higgins (Ed.): Handbook of Australian, New Zealand & Antarctic Birds. Volume 1, Ratites to Ducks, Oxford University Press, Oxford 1990, ISBN 0-19-553068-3 .

- John Gooders, Trevor Boyer: Ducks of Britain and the Northern Hemisphere. Dragon's World, Surrey 1986, ISBN 1-85028-022-3 .

- Hartmut Kolbe: The world's ducks. 5th edition. Ulmer, Stuttgart 1994, ISBN 3-8001-7442-1 .

- Scott Nielsen: Mallards. Voyageur Press, Stillwater 1992, ISBN 0-89658-172-1 .

- Erich Rutschke: The wild ducks of Europe. Biology, ecology, behavior. Aula, Wiesbaden 1988, ISBN 3-89104-449-6 .

Web links

- Anas platyrhynchos in the endangered Red List species the IUCN 2008. Posted by: BirdLife International, 2008. Accessed January 2 of 2009.

- Videos, photos and sound recordings of Anas platyrhynchos in the Internet Bird Collection accessed on January 16, 2015

- Mallard Feathers , accessed on January 16, 2015

- Videos on Anas platyrhynchos published by the Institute for Scientific Film .

Individual evidence

- ↑ Rutschke, p. 197 - The notation Merzente was also common

- ↑ Rutschke, p. 197.

- ↑ Viktor Wember: The names of the birds of Europe. Meaning of the German and scientific names. Aula, Wiebelsheim 2007, ISBN 978-3-89104-709-5 , p. 83.

- ↑ Rutschke, p. 23.

- ↑ Rutschke, p. 22 and Kolbe, p. 211.

- ↑ Rutschke, p. 205.

- ^ Collin Harrison and Peter Castell: Field Guide Bird Nests, Eggs and Nestlings. HarperCollins, London 2002, ISBN 0-00-713039-2 , p. 71.

- ↑ Rutschke, p. 19.

- ↑ Hans-Heiner Bergmann, Hans-Wolfgang Helb, Sabine Baumann: The voices of the birds of Europe. 474 bird portraits with 914 calls and chants on 2200 sonograms. Aula, Wiesbaden 2008, ISBN 978-3-89104-710-1 , p. 57.

- ↑ Christopher S. Smith: Field Guide to Upland Birds and Waterfowl. Wilderness Adventure Press, Belgrade (Montana) 2000, ISBN 1-885106-20-3 , p. 56.

- ↑ Bruno Caula, Pier Luigi Beraudo and Massimo Pettavino: Birds of the Alps - The destination guide for all species. Haupt Verlag, Bern 2009, ISBN 978-3-258-07597-6 , p. 28.

- ↑ a b Gooders and Boyer, p. 48.

- ^ Higgins, p. 1313.

- ↑ a b c d Higgins, p. 1314.

- ^ Higgins, p. 1315.

- ^ Higgins, p. 1333.

- ↑ a b Rutschke, p. 200.

- ↑ a b Rutschke, p. 201.

- ↑ a b Rutschke, p. 36.

- ↑ Rutschke, p. 40.

- ↑ Janet Kear: Man and Wildfowl. Poyser, London 1990, ISBN 0-85661-055-0 , pp. 199 and 200

- ↑ a b Gooders and Boyer, p. 50.

- ↑ Nielsen, p. 51.

- ↑ a b Rutschke, p. 61.

- ↑ Gooders and Boyer, p. 51.

- ↑ Rutschke, p. 202.

- ↑ Nielsen, p. 7.

- ↑ State Association for Bird Protection in Bavaria e. V .: Duck broods on balconies or flat roofs

- ^ Willson Bulletin, December 1974. P. 462 . Retrieved May 11, 2020

- ↑ The record flight of a duck from Hessen to Russia

- ↑ Federal Agency for Nature Conservation : Mallard ( Memento from August 4, 2017 in the Internet Archive ), accessed on August 3, 2017

- ↑ Annual route wild ducks , accessed on August 3, 2017

- ↑ The hunting statistics of Austria do not break down the species of wild ducks.