Visoki Dečani Monastery

| Visoki Dečani | |

|---|---|

|

UNESCO world heritage |

|

|

|

| National territory: |

(On the territory of Kosovo, listed under Serbia by UNESCO .) |

| Type: | Culture |

| Criteria : | ii, iii, iv |

| Reference No .: | 724 |

| UNESCO region : | Europe and North America |

| History of enrollment | |

| Enrollment: | 2006 (session 30) |

Coordinates: 42 ° 32 ′ 49.2 ″ N , 20 ° 15 ′ 58.4 ″ E The Visoki Dečani Monastery ( Dečani for short) is a medieval Serbian Orthodox monastery in Kosovo . Based on the Apulian Gothic style , it is one of the later works of the Raška school . It is the tomb of King Stefan Uroš III. Dečanski and an important pilgrimage center. The king's coffin is in the nave in front of the iconostasis . The church , consecrated to Christ Pantocrator , houses the only fresco ensemble of Byzantine art that has been completely preserved from the Middle Ages. The church was started in the last years of his life by Stephan Dečanski and completed by his son Stefan Dušan .

location

The monastery is located above the town of Dečani / Deçan , 17 km south of Peć / Peja at the exit of Dečanski potok in the eastern Prokletije in Kosovo .

history

Emergence

This monastery is the largest building in medieval Serbia . It was in the years from 1328 to 1335 by the Kotoran Franciscan Fra Vita as a burial place for Stefan Uroš III. Dečanski built.

Through the canonization of Stefan Uroš III. Dečanski and the hagiography of King Stefan Dečanski, written there at the time of Stefan Lazarević , in the early 15th century, by the important Bulgarian writer Grigorij Camblak (1402–1409 Iguman of the monastery) , it quickly gained great importance as a place of pilgrimage.

Kosovo conflict

Until the tensions in the Kosovo conflict , it is said to have been an old tradition for both Orthodox Serbs and Muslim and Catholic Albanians from the city and the surrounding area to come to the monastery, especially in anticipation of the miraculous healing power of the relics .

In April and May 1998 the UÇK , which, as the Albanian rebel organization , had announced on January 4, 1998 that it would fight as an armed force of the Albanians until the unification of Kosovo with Albania , advanced into central Kosovo in an offensive , bringing ever larger areas of the Kosovo came under their control and controlled the most important traffic routes between Pristina , Peć and Montenegro . According to the abbot of Dečani Monastery, Sava Janjić, the Kosovar Albanians are said to have expelled the Serbs to the villages near the monastery and "ethnically cleansed" the area. When the UÇK occupied the connecting roads from Dečani to Peć and Đakovica in late May and early June , Serbian units captured the town of Dečani, which they described as a depot for arms smuggling from Albania. During the Serbian-Yugoslav counter-offensive from May 24th with the aim of smashing the UÇK, recapturing the "liberated areas" with the most important communication links and supply lines and controlling the border region to Albania, numerous Serbian police officers and up to 100 Kosovar Albanians killed. Thousands of residents fled to neighboring regions. Ultimately, the development resulted in NATO's military intervention in 1999.

Public presentation and politics of the monastery tour from 1998

Archmonk Sava Janjić ( Father Sava ), who has been active in Dečani Monastery since 1992 , and at the same time secretary to the Bishop of the Diocese of Raška and Prizren , Artemije (Artemije Radosavljević), joined the monastery by e-mail internationally, which was temporarily cut off from the outside world by the security situation from 1997 onwards, at a time when the civil, police and military authorities in Kosovo did not have an internet connection. Sava Janjić, who had studied English , had an unusually good command of English in this region at the time, gained international popularity in 1998 via the monastery’s internet domain http://www.decani.yunet.com/ and was often referred to as “cyber monk” by foreign journalists “(Cyber Monk) titled. In an equally unusual way, Sava Janjić as abbot of the monastery with a Serbian delegation was sent by Slobodan Milošević to negotiations mediated by Milan Panić from the USA in The Hague before the Rambouillet conferences . Radosavljević and Janjić are said to have called on moderate Kosovar Serbs and Kosovar Albanians for dialogue at an early stage, like the chairman of the Serbian Resistance Movement in Kosovo, Momčilo Trajković. Radosavljević and Trajković spoke out against repression by the Serbian police and against Kosovar-Albanian terrorist attacks.

Janjić several times denied messages that were supposed to discredit the monastery via electronic communication. For example, when the information center of the Kosovar Albanian LDK led by Ibrahim Rugova reported that the monastery had given shelter to Serbian paramilitaries, according to the UÇK guerrilla . Or when the Kosovar Albanian newspaper Koha Ditore claimed that the Serbian nationalist leader Vojislav Šešelj had met with monks in the monastery.

Janjić was spokesman for the Serbian National Council for Kosovo and a member of the Provisional Administrative Council of Kosovo.

The visit by US Vice President Joe Biden sparked discussions . While Sava Janjic expressed the hope that the visit would help preserve the Serbian Orthodox cultural heritage in Kosovo and help the Serbian people in Kosovo, the diocese of Raška and Prizren strongly condemned the form of the visit. The US Vice President visited Kosovo as an independent state to "confirm a violent secession of Serbian territory by Albanian terrorists who have not been punished for their countless crimes against Serbian people, Serbian property and Serbian secular and religious cultural assets." . The visit had made the monastery a symbol against the interests of Serbia, whereby the diocese made a comparison with Camp Bondsteel as a US American base in Kosovo.

Architecture and art

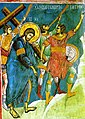

The church is a five-aisled basilica with a three-aisled exonarthex . The tall columns and the cross vaults used in Serbia only in Dečani and the Gothic windows reveal a strong western influence. At the main entrance of the church, as well as in the narthex portal and the column capitals, there are excellent works of stone carving, including the seated figure of Christ Pantocrator, lion heads on the capitals and lion sculptures on the narthex portal. The frescoes , completed between 1335 and 1350, are among the most important examples of the Palaiological Renaissance . It was made by masters from the Ohrid painting school . The abundance of images and theological scenes dealt with are captivating due to the richly figurative and color-accentuated representation. Among other things, the portraits of rulers and the family tree of the Nemanjid dynasty are important .

The artistic importance of the monastery is the complete decoration of the church with frescoes. Because of this importance was the king Stefan Uroš III. Dečanski later added the name “Dečanski”. Today the monastery is the center of the cult around Saint Stephen Uroš III. Dečanski. His son, King Stefan Uroš IV. Dušan (ruled 1336–1356) completed the monastery in his father's name.

The church is completely decorated with frescoes. They are the best-preserved ensemble of frescoes in Southeast Europe in the Middle Ages. The treasury contains valuable icons from the 14th to 16th centuries. Century and works of church handicrafts. The grave of St. Stefan Uroš III. Dečanski is an important Orthodox place of worship. The carved wood sarcophagus stands on a marble plinth, and pilgrims crawl around it crawling on the floor.

The frescoes inside the church (1335–1350) are based on Byzantine models (see: Serbian-Byzantine style ). The wrought iron candlestick (choros) is a major work of metalworking in medieval art. To the left of the iconostasis is the wooden sarcophagus of Stefan Uroš III. Dečanski.

World heritage and security situation

In 2004 the monastery was declared a World Heritage Site by UNESCO . Because of the legally unclear situation in Kosovo and the difficult security situation, it was also entered on the Red List of World Heritage in Danger.

The monastery, in which Serbs, Kosovar Albanians and Roma are said to have found refuge during the Kosovo war, is said to have been the target of mortar attacks four times since KFOR arrived in Kosovo in 1999 (six grenades in February 2000, nine in June 2000, seven on March 17, 2004 and another on March 30, 2007). Overall, it is said to have been "around a dozen times the target of attacks by Albanian extremists" in recent years (as of 2008). The mighty outer wall and intensive guarding in the area of responsibility of Italian KFOR soldiers is attributed to the fact that, in contrast to many other Christian Orthodox sacred sites in Kosovo, it has remained largely unscathed. The city of Dečani is considered to be the stronghold of the supporters of the UÇK leader Ramush Haradinaj , who was responsible for this region during the Kosovo war , who was acquitted as a war criminal by the ICTY in 2008 and 2012 for lack of evidence, but by the Federal Intelligence Service (BND) as one of the key figures between Politics and Organized Crime is classified, and its party, the AAK . The monks of the monastery do not do their shopping in the city, but go to Montenegro or Serbia once a year in a KFOR escort (status: 2007). After Kosovo's declaration of independence, the monks of the monastery are said to have been denied 25 hectares of land by the city of Dečani, which they cultivate for food production. The UN mission is said to have accused the city authorities of forging land registers and awarded the property to the monks, which the city politicians in Dečani ignored.

literature

- Života Đorđević, Svetlana Pejić (ed.): Cultural Heritage of Kosovo and Metohija . Institute for the Protection of Cultural Monuments of the Republic of Serbia, Belgrade 1999.

- Branislav Krstić: Saving the Cultural Heritage of Serbia and Europe in Kosovo and Metohia . Coordination Center of the Federal Government and the Government of the Republic of Serbia for Kosovo and Metohia, Belgrad 2003.

- Miodrag Marković, Dragan Vojvodić (eds.): Serbian Artistic Heritage in Kosоvo and Metohija: Identity, Significance, Vulnerability . Serbian Academy of Sciences and Arts, Belgrade 2017.

- Bratislav Pantelić: The Architecture of Dečani and the Role of Archbishop Danilo II . Reichert, Wiesbaden 2002.

- Mirjana Šakota: Ottoman Chronicles: Dečani Monastery Archives . Diocese of Raška-Prizren, Prizren 2017.

- Gojko Subotić: Art of Kosovo: The Sacred Land . The Monacelli Press, New York 1998.

- Branislav Todić, Milka Čanak-Medić: The Dečani Monastery . Museum in Pristina, Belgrade 2013.

- Tibor Živković, Stanoje Bojanin, Vladeta Petrović (eds.): Selected Charters of Serbian Rulers (XII-XV Century): Relating to the Territory of Kosovo and Metohia . Center for Studies of Byzantine Civilization, Athens 2000.

Web links

- Official website of the monastery (Serbian, English and other languages)

- Evaluation of Visoki Decani by the World Heritage Committee (PDF; 327 kB)

- Entry in the UNESCO World Heritage List (English) (French)

- The Economist on the life of the monks in the monastery: Serb monks in Kosovo Preparing for the next 700 years

Individual evidence

- ↑ [1]

- ↑ a b c d e f g Matthias Rüb: Kosovo - causes and consequences of a war in Europe. DTV, Munich, November 1999, ISBN 3-423-36175-1 , pp. 93-95.

- ↑ Heinz Loquai: The Kosovo conflict - ways into an avoidable war: the period from the end of November 1997 to March 1999. Nomos Verlagsgesellschaft, Baden-Baden 2000, ISBN 3-7890-6681-8 , pp. 45, 170.

- ^ A b Wolfgang Petritsch, Robert Pichler: Kosovo - Kosova - The long way to peace. Wieser, Klagenfurt et al. 2004, ISBN 3-85129-430-0 , p. 220f.

- ^ A b Carl Polónyi: Salvation and Destruction: National Myths and War using the Example of Yugoslavia 1980-2004. Berliner Wissenschafts-Verlag, 2010, ISBN 978-3-8305-1724-5 , pp. 279f.

- ↑ a b Traitor to the national cause? - Voices against the war in Kosovo are loud from the Serbian Church ( Memento from February 12, 2013 on WebCite ) , The Overview - Journal for Ecumenical Encounters and International Cooperation, Issue 3/1998, by Klaus Wilkens, p. 40, archived by the Internet version of the Christian-Islamic Society on February 12, 2013.

- ↑ Wolfgang Petritsch, Karl Kaser, Robert Pichler: Kosovo - Kosova: Myths, data, facts. 2nd Edition. Wieser, Klagenfurt 1999, ISBN 3-85129-304-5 , p. 221ff

- ↑ a b c d e f g The good person of Decani - How a Serbian Orthodox monk campaigns for Kosovar Albanians in the almost completely destroyed city ( Memento from February 12, 2013 on WebCite ), Berliner Zeitung, July 28, 1998 , by Thomas Schmid, archived from the original .

- ↑ a b c d Wolfgang Kaufmann: The observers. Books on Demand, Norderstedt 2004, ISBN 3-8334-1200-3 , pp. 151-154.

- ↑ a b c d e Struggle for Status - The Lords of Kosovo ( Memento from February 12, 2013 on WebCite ) , Der Tagesspiegel, July 24, 2007, by Ingrid Müller, archived from the original .

- ↑ Biden visit to Kosovo monastery splits Serbian Orthodox Church ( Memento from February 12, 2013 on WebCite ) (English). Reuters Edition US, May 22, 2009, by Adam Tanner, archived from the original .

- ↑ SPC overrules bishop's decision ( Memento from February 12, 2013 on WebCite ) (English). B92, May 20, 2009, archived from the original .

- ↑ World Heritage Committee puts Medieval Monuments in Kosovo on Danger List and extends site in Andorra, ending this year's inscriptions ( Memento of February 6, 2013 on WebCite ) , UNESCO, communication, July 13, 2006, archived from the original .

- ↑ a b c Orthodox monks fear independence ( memento from February 12, 2013 on WebCite ), Die Welt, August 15, 2007, by Nina Mareen Spranz, archived from the original .

- ↑ Kosovo Albanians Attack Decani Monastery ( Memento from February 10, 2013 on WebCite ) , De-Construct.net, March 30, 2007, archived from the original .

- ↑ UNESCO world heritage site targeted by extremists again - Decani Monastery area hit by a mortar-grenade, no injuries or damage ( Memento from February 10, 2013 on WebCite ) , KIM Info-service, KiM Info Newsletter, March 30, 2007, archived from the original .

- ↑ Kosovo monastery Visoki Decani blocked ( Memento from February 10, 2013 on WebCite ) , Tanjug, February 8, 2013.

- ↑ a b c d [Kosovo: Hard situation for Serbian monks], Deutsche Welle , October 23, 2008, by Filip Slavkovic, (Permalink: http://dw.de/p/FfSI ), archived from the original .

- ↑ La Guerra Infinita - Kosovo Nove Anni Dopo (Italian, TV documentary). Rai Tre , by Riccardo Iacona , in collaboration with Francesca Barzini, broadcast on Rai Tre on September 19, 2008. Available on popular video portals (also with English and Serbian subtitles, last accessed on February 9, 2013).

- ^ Carl Polónyi: Salvation and Destruction: National Myths and War Using the Example of Yugoslavia 1980-2004. Berliner Wissenschafts-Verlag, 2010, ISBN 978-3-8305-1724-5 , p. 437.

- ^ A b Wolfgang Petritsch, Robert Pichler: Kosovo - Kosova - The long way to peace. Wieser, Klagenfurt et al. 2004, ISBN 3-85129-430-0 , p. 304.

- ↑ Haradinaj, Balaj, and Brahimaj Acquitted on Retrial ( February 12, 2013 memento on WebCite ), ICTY, press release, November 29, 2012, archived from the original .

- ↑ Four years after the Kosovo war - the Solana state falls apart ( Memento from February 13, 2013 on WebCite ), Le Monde diplomatique, No. 6980, February 14, 2003, pages 10–11, 287 documentation, by Jean-Arnault Dérens ( German by: Christian Hansen), archived from the original .