Serbian-Byzantine style

The Serbian-Byzantine style is a combination of three successive styles of Byzantine art in medieval Serbia between the 12th century and the end of the 16th century. The Raška school in the 12th to 13th centuries is characterized by the architectural fusion of western Romanesque and eastern Byzantine elements . From the Byzantine and Bulgarian art centers in Thessaloniki , Ohrid , the Athos , the style of the Palaiological Renaissance is binding from the time of Stefan Uroš II Milutin (1282–1321) . In particular, a different treatment of the structure in this so-called Macedonian School reveals the development of a Serbian-Byzantine architectural style that was fully developed in the buildings of the Morava School in the final period of Byzantine art in Serbia . The most innovative and experimental buildings of Byzantine architecture belong to the harmoniously balanced group of churches and monasteries in northern Serbia with their diverse new elements .

Raška school

The Raška School includes the oldest ecclesiastical buildings in Serbia with the exception of the Petrova crkva , which was built as early as the 9th century and , as a rotunda, is committed to the Byzantine classical period under Justinian. The Raška School includes in particular the monastery churches of Studenica , Žiča , Mileševa (monastery) , Sopoćani and the Gradac monastery . The artistic center of the Raska School was Raszien around Stari Ras , the old Serbian capital.

architecture

The churches are designed as cruciform basilicas with a cupola. The foundation building and model for later foundations is the Church of Our Lady in Studenica . With the exception of the dome, the buildings are built in the Romanesque style. The architectural style is conveyed to Serbia via the Dalmatian coastal towns (especially Dubrovnik and Kotor ).

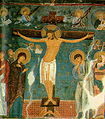

Frescoes

The frescoes in the churches of the Raška school are purely Byzantine works of an amazing level. The blue or gold background in Studenica and the emotional depiction of the crucifixion of Christ are characteristic . The depiction of the angel at the tomb of Christ in Mileševo as well as the monumental antique frescoes in Sopoćani, belonging to the early Renaissance , stand on a green background.

Macedonian school

With the stronger Byzantine artistic influence since the beginning of the 14th century, the structural center also moved to Kosovo and Macedonia. This is where the main works of the Macedonian School were created , which culminated in the Gračanica monastery church .

architecture

A direct Greek influence can be felt in the architecture of Milutin's buildings through mediation through the architecture in Thessaloniki. However, the height of the buildings erected in Serbia is unknown in Byzantine art of that time. For the first time, five-domed churches are being built in Serbia. Cross-dome churches with five domes are Gračanica (1311–1321), Staro Nagoričane (1317–18) and Bogorodica Ljeviška (1310–13). In addition to these main works, there are also simpler churches with only one dome, such as the Church of St. Archangel Michael in Lesnovo, but especially the royal chapel (royal church) in the Studenica monastery .

Frescoes

Iconostasis and wrought-iron chorus , Dečani Royal Monastery ( Raška School ), 1328–1335

Portrait of the founder Stefan Lazarević , Manasija Monastery ( Morava School ), 1407–1418

The paleological renaissance found its way into Serbian painting through the two court painters of King Milutin, Michael Astrapas and Eustychios . The moving, detailed figures are more stylized than the monumental painting of the Raška school . The painters of the Serbian monasteries come from the painting school of Ohrid . The fresco cycle in the Visoki Dečani monastery represents a special position . The monastery is built in the Apulian Gothic style and belongs to the context of the Raska school; The style and richness of figures make the frescoes of the Macedonian School, but do not reach the quality of the frescoes by Bogorodica Ljeviška , the royal church in Studenica or Gračanica.

Icons

Only a few icons have survived from that period, e.g. B. the five standing icons of the iconostasis in Decani. The long-limbed figures and fine drawings are extremely elegant. The icons that have been preserved in Ohrid are significant . They show a lavish use of gold ground.

Morava school

The last phase of Serbian art in the Middle Ages, the Morava school, is an independent achievement of Serbian art, which admittedly takes up elements of the Athos monasteries, but designs a fundamentally new scheme for church building. As an international style, this Serbian style is also effective across national borders ( Moldavian monasteries , Wallachia ).

architecture

The three-icon systems are characterized by the colored brick decoration of the facade and rich sculptural decoration in bas-relief technology.

Frescoes

It was not until the painting of the Morava school that a more realistic representation was intended. The frescoes in Kalenić and Manasija achieve a stylistic delicacy and elegance that draws level with the best works of Gothic art. The program in Kalenić and Manasija can be seen as the beginning of the early Renaissance in painting in Serbia.

Icons

Among the icons of the late 14th and 15th centuries, the large-format icons of the Hilandar Monastery stand out.

literature

General

- Helen C. Evans, ed., Byzantium: Faith and Power (1261-1557), exh. cat. New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art; New Haven: Yale University Press, 2004. 658 pp., 721 color ills., 146 b / w.

painting

- Slobodan Ćurčić: Some Uses (and Reuses) of Griffins in Late Byzantine Art . In: Byzantine East, Latin West: Art-Historical Studies in Honor of Kurt Weitzmann, edited by Christopher Moss and Katherine Kiefer, pp. 597-604. Princeton, 1995.

- Vojislav J. Durić: La peinture murale de Resava: Ses origines et sa place dans la peinture byzantine . In: Moravska skola i njeno doba: Nauchmi skup u Resavi 1968 / L'École de la Morava et son temps: Symposium de Résava 1968, edited by Vojislav J. Duric, pp. 277-91. Belgrade, 1972.

- Tania Velmans : Infiltrations occidentales dans la peinture murale byzantine au XIVe et au début du XVe siècle . In: Moravska skola i njeno doba: Nauchmi skup u Resavi 1968 / L'École de la Morava et son temps: Symposium de Résava 1968, edited by Vojislav J. Duric, pp. 37-48. Belgrade, 1972.

architecture

- Slobodan Ćurčić: Religious Settings of the Late Byzantine Sphere . In: Byzantium: Faith and Power (1261–1557), edited by Helen Evans (The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, 2004).

plastic

- Nadežda Katanić: Decorative camea plastika Moravske škole . Prosveta, Republički zavod za zaštitu spomenika kulture, Beograd, 1988. ISBN 86-07-00205-8

Individual evidence

- ^ A b Gerhard Podskalsky : Theological Literature of the Middle Ages in Bulgaria and Serbia 815-1459 , Munich, Beck, 2000, ISBN 3-406-45024-5