Cash in German marks

|

Deutsche Mark June 21, 1948 to December 31, 2001 |

|

|---|---|

| Country: |

|

| Subdivision: | 100 Pfennig (abbreviated: Pf) |

| ISO 4217 code : | DEM |

| Abbreviation: | DM, DEM, D-Mark |

|

Exchange rate : (fixed) |

1 EUR = 1.95583 DEM |

The cash of the Deutsche Mark was issued with the currency reform on June 20, 1948 by the Bank of German Lands under the sovereignty of the three Western Allies France , USA and United Kingdom in the form of coins and banknotes . It replaced the cash of the Reichs- and Rentenmark as well as the banknotes of the Allied Military Currency (AMC) from the Allied Military Authority.

Immediately after the currency reform, every natural person in the three western zones of Germany received a "bounty" of 40 DM and a month later a further 20 DM were paid out in cash, which were offset against the later conversion of the Reichsmark. This regulation did not apply to the Saarland , as the D-Mark was only introduced there on July 6, 1959. In the three western sectors of Berlin there was a special situation in that the D-Mark was initially introduced as a secondary currency to the Ostmark and was only declared the sole legal tender by the Western Allies on March 20, 1949 . On July 1, 1990, the cash of the Deutsche Mark became the only legal tender in the territory of the GDR .

The appearance of the coins remained largely unchanged during the five decades that the D-Mark was legal tender, while there were four officially issued series of banknotes. Between 1950 and 2000, the currency in circulation grew steadily from 7.8 to 244.8 billion German marks. Although the security features were continuously improved, the DM banknotes were the second most common counterfeit currency after the US dollar bills .

With the introduction of euro cash on January 1, 2002, the coins and banknotes of the Deutsche Mark lost their legal tender status. Since then, the Deutsche Bundesbank has been exchanging D-Mark coins and banknotes for euros at the fixed rate. According to the Deutsche Bundesbank, D-Mark cash with a nominal value of 12.76 billion D-Mark (= 6.52 billion euros) had not yet been exchanged on June 30, 2016; this corresponds to around 4.7 percent of the cash holdings in 2000. The sum is divided into 6.01 billion marks in banknotes and 6.75 billion marks in coins.

Coins

Through the law for the “establishment of the Bank of German States ” of March 1, 1948, this bank received the sole authorization to issue banknotes and coins. The first coin was the 1-pfennig coin designed by Adolf Jäger , which came into circulation on January 24, 1949 with a total mintage of almost 240 million. The 10-pfennig coin followed on May 21, 1949, the 5-pfennig coin on January 2, 1950 and the 50-pfennig coin on February 14, 1950. These 5 and 50 pfennig coins also bore the year 1949.

With the "announcement on the issue of coins with a face value of 1, 5, 10 and 50 Pfennig, which instead of the writing 'Bank deutscher Länder' have the inscription 'Federal Republic of Germany'" of May 6, 1950, these denominations were made mandatory instead of the inscription "BANK DEUTSCHER LÄNDER", the inscription "BUNDESREPUBLIK DEUTSCHLAND" should be used if they were issued with the year of issue "1950". Through the federal law on the issue of token coins of July 8, 1950 (Federal Law Gazette, p. 323), the coin shelf was transferred to the federal government ( Federal Ministry of Finance ). For this reason, since mid-1950, all other new D-Mark coins have been labeled as “BUNDESREPUBLIK DEUTSCHLAND”. Paragraph 1 of this law also listed the individual denominations that could be issued. Since the legal basis for the denominations, which had already been provided with the new transcription from May 1950, was not replaced by a new one, these four denominations continued to be issued with the year "1950" until 1965. Since a change in the law in December 1986, it has also been possible to mint coins over 10 Deutsche Mark.

Illustrations and dimensions

All coins were made in reverse coinage ; d. That is, in order to also see the reverse side upright after looking at the front side, the coin must be rotated about the vertical axis.

| Face value | image | draft | metal | Diameter in mm | Thickness in mm | Mass in grams | Embossing years | issue date | Discontinuation on |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 pfennig |

|

Adolf Jäger , Frankfurt am Main |

Steel core plated with copper | 16.5 | 1.38 | 2 | 1948–1949 (BDL) 1950, 1966–2001 (FRG) |

January 24, 1949 (BDL) May 6, 1950 (FRG) |

January 1, 2002 (all) |

| 2 pfennigs |

|

Based on the design by Adolf Jäger | 95% copper, 4% tin, 1% zinc | 19.25 | 1.52 | 3.25 | 1950, 1958-1968 | October 23, 1950 | January 1, 2002 |

| Steel core plated with copper | 2.9 | 1968-2001 | |||||||

| 5 pfennigs |

|

Adolf Jäger, Frankfurt am Main |

Steel core plated with brass | 18.5 | 1.7 | 3 | 1949 (BDL) 1950, 1966-2001 (FRG) |

January 2, 1950 (BDL) May 6, 1950 (FRG) |

January 1, 2002 (all) |

| 10 pfennigs |

|

Adolf Jäger, Frankfurt am Main |

Steel core plated with brass | 21.5 | 1.7 | 4th | 1949 (BDL) 1950, 1966-2001 (FRG) |

May 21, 1949 (BDL) May 6, 1950 (FRG) |

January 1, 2002 (all) |

| 50 pfennigs |

|

Richard M. Werner, Oberursel (Taunus) |

Cupronickel | 20th | 1.58 | 3.5 | 1949 (BDL) 1950, 1966-2001 (FRG) |

February 14, 1950 (BDL) May 6, 1950 (FRG) |

January 1, 2002 (all) |

| 1 DM |

|

Josef Bernhart, Munich |

Cupronickel | 23.5 | 1.75 | 5.5 | 1950, 1954-2001 | December 18, 1950 | January 1, 2002 |

| 2 DM |

|

Josef Bernhart, Munich |

Cupronickel | 25.50 | 1.79 | 7th | 1951 | May 8, 1951 | July 1, 1958 |

|

Karl Roth , Munich |

Cupronickel | 26.75 | 1.79 | 7th | 1957-1971 | June 21, 1958 | 1st August 1973 | |

|

Picture side: various designs, constant value side: Reinhart Heinsdorff , Lehen |

Magnimat | 26.75 | 1.79 | 7th | 1969–1987 ( Adenauer ) 1970–1987 ( Heuss ) 1979–1993 ( Schumacher ) 1988–2001 ( Erhard ) 1990–2001 ( Strauss ) 1994–2001 ( Brandt ) | since December 28, 1970 (Adenauer) | January 1, 2002 (all) | |

| 5 DM |

|

Albert Holl, Schwäbisch Gmünd |

62.5% silver, 37.5% copper | 29 | 2.07 | 11.2 | 1951, 1956-1961, 1963-1974 | May 8, 1952 | August 1, 1975 |

|

Wolfgang Doehm , Stuttgart |

Magnimat | 29 | 2.07 | 10 | 1975-2001 | 1st February 1975 | January 1, 2002 | |

| BDL: coins with inscription "Bank deutscher Länder" BRD: coins with inscription "Federal Republic of Germany"

|

|||||||||

Mints

| character | Minting time | Mint | Embossing key | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| from | to | 1948-1990 | 1991-2001 | ||

| A. | 1990 | 2001 | State Mint Berlin | not applicable | 20% |

| D. | 1948 | 2001 | Bavarian main mint | 26% | 21% |

| F. | 1948 | 2001 | State Mint Stuttgart | 30% | 24% |

| G | 1948 | 2001 | State Mint Karlsruhe | 17.3% | 14% |

| J | 1948 | 2001 | Hamburg Mint | 26.7% | 21% |

|

|||||

The coins were produced in five different mints (see table opposite). The mint marks on the coins provide information about the mint in which the respective coin was produced. In Berlin , DM coins were not minted until June 1990, after the agreement on the creation of a monetary, economic and social union was signed on July 1, 1990; GDR coins were previously made here. The regular production of course coins was stopped in 1996. However, until 2001, currency sets were minted in significantly smaller numbers.

Small coins

The 2-pfennig coin until 1968 consisted of a massive 95 percent copper alloy. After that, like the small coins of 1, 5 and 10 pfennigs, it was minted in inferior quality on iron discs , the top and bottom of which were only thinly coated with a layer of copper or brass. As a result, they began to rust easily if they were exposed to humid weather for a long time without protection.

Unlike the higher-value coins, the small coins were uniform in their design. They bore the value, the mint mark and two ears of corn on the obverse and the inscription " Bank deutscher Länder " or "Federal Republic of Germany", the year and an oak branch with five leaves on the reverse .

One of Jäger's two designs provided for three interlaced rings on the reverse of the coins, which obviously symbolized the three western zones that were to be connected to form a currency union. But because the tender for the 1-, 5- and 10-pfennig coins stipulated that the designs should "not express any political tendencies", the other design with the oak branch was selected. The tender also stipulated that the lettering “must” be done in Antiqua in order to distinguish it from the coins from the Nazi era from 1933 on which the Gothic script was used.

Rather, it should be linked to the “material value tradition of the prewar period”. For this reason, the 1-pfennig piece was designed as a copper coin weighing exactly two grams, as it has been minted since the imperial era from 1873. However, since the material value of an almost pure copper coin (the model consisted of the same alloy as the 2-pfennig piece until 1968) would have exceeded the face value, an iron coin was minted that was simply plated with copper.

50 pfennig coin

The kneeling woman depicted on the reverse of the 50 pfennig coin is Gerda Johanna Werner . She is planting an oak tree - a symbol of the reconstruction of Germany after the Second World War. Her husband Richard Martin Werner , who designed the picture, wanted to pay tribute to the work of the millions of rubble women , but also the numerous forest workers who work in reforestation.

With the production of the new 50-pfennig coin, the mints began in 1949 with the inscription "Bank deutscher Länder". In 1950 the inscription was changed to "Federal Republic of Germany", but Karlsruhe (G) let the machines continue to run for a short time with the new year and the old inscription. The 30,000 incorrect coins with the old romanization were not withdrawn for reasons of cost. This resulted in sought-after collector's items, which, depending on their state of preservation, are traded for up to 3000 euros. At the beginning of the 1970s, these were illegally minted in the Karlsruhe coin scandal .

The 50-pfennig coins were initially the only DM coins to have a fluted edge . From 1972, the 50-pfennig pieces were minted with a smooth edge in order to reduce production costs.

The size ratio of the 50-pfennig coin to the 1-mark piece goes back to the size ratio of the silver coins in the German Reich up to 1918 . At that time the 50-pfennig coin, or later the “half mark”, was also equivalent in material value to half a mark. The diameter of the 50-pfennig coin was unchanged at 20 millimeters. The diameter of the 1 D-Mark coin only differed by half a millimeter from the diameter of the Silbermark. In contrast, the proportions differ in terms of mass and thickness.

1 DM coin

The 1-mark coin was the first coin on which the currency designation "Deutsche Mark" was minted; the coins previously issued bore the designation "pfennig". Like the 50-pfennig piece, it was made of cupronickel. Two of the most common German symbols are depicted on the coin: oak leaves on the obverse and the federal eagle on the reverse. While the other previously issued coins had a smooth or fluted edge, the edge of the 1 DM coin was decorated with arabesques .

2 DM coin

The first 2 DM coin was issued on May 8, 1951. The design came from Josef Bernhart from Munich based on the 1 DM coin that he also designed.

With the same reverse side, the coin was two millimeters larger than the 1-mark piece, next to the value number were shown ears of corn and grapes instead of oak leaves, and the edge was decorated with the text “Unity and Law and Freedom” instead of arabesques; but because these differences were only minor, there was often confusion with the 1 DM coin. Even banks struggled to tell the two coins apart.

Because of these difficulties, the Bundestag decided on September 30, 1955 to replace the coins in circulation with a new, distinctive coinage. On March 13, 1957, the federal government had to decide on the design of the coin. The physics Nobel Prize winner Max Planck , the physician Robert Koch and the engineer Oskar von Miller were available. Interior Minister Gerhard Schröder was unable to support Vice Chancellor Franz Blücher's proposal to issue another coin with a different portrait of a person from across the Oder-Neisse Line , as he did not consider two motifs with the same face value to be useful. In the end, the portrait of Max Planck, on the occasion of his 100th birthday, was chosen by Karl Roth . In addition, it was decided to emphasize the value figure more conspicuously. On June 21, 1958, the new 2-mark piece with a slightly larger diameter of 26.75 mm and a newly designed federal eagle on the value side was issued. On June 30, 1958, only nine days after the introduction of the new coin, the old 2-DM coin was suspended and lost its validity as legal tender; it could be exchanged until September 30, 1958.

But the introduction of the new coin did not solve all problems either: initially there were still confusions, this time with the 5-mark coin. In addition, it was not machine-safe. Many foreign coins with the same dimensions and the same alloy were accepted by the machines as 2 DM, although some of them had a significantly lower value.

On February 2, 1969, it was announced that there would be a new 2 DM coin with the image of Konrad Adenauer , the first Federal Chancellor of the Federal Republic of Germany, which would replace the Max Planck coins. Instead of a simple copper-nickel alloy (75% Cu, 25% Ni), Magnimat was used as the material. Magnimat consists of a pure nickel core (7% for the 2 DM coin), onto which a layer of copper nickel is rolled on at the front and back. The changed magnetic properties could be reliably recognized by the machines. Minting started in 1969. The first coins were issued on December 28, 1970. For logistical reasons, only a small part was initially put into circulation. Since new coins with the portrait of Max Planck were also issued (they were minted until 1971), the rumor spread among speculators and collectors that the federal government , which has now been formed by a coalition of the SPD and FDP, does not have a CDU -Politicians on the coins would tolerate. This meant that collectors sometimes paid up to 5 DM for an Adenauer coin.

On July 1, 1973 (when a social-liberal coalition was still ruling), the Adenauer coin was issued in large numbers together with the Theodor Heuss coin, which had the same specifications (size, mass, alloy). The Max Planck coin was suspended on July 31, 1973 and thus disappeared from the money cycle.

More 2 DM coins of this type followed with images of deceased politicians in the Federal Republic. They were issued on the occasion of a major anniversary of the Federal Republic (1969, 1979, 1989, 1994) or the D-Mark (1988). The following table gives an overview of the six coins in the Politician series:

| Depicted politician | image | draft | occasion | Embossing years | issue date |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Konrad Adenauer (CDU) (1876–1967) first Federal Chancellor (1949–1963) |

|

Reinhart Heinsdorff fief |

20 years of the Federal Republic of Germany 1949–1969 |

1969-1987 | December 28, 1970 (see text) |

|

Theodor Heuss (FDP) (1884–1963) first Federal President (1949–1959) |

|

Karl-Ulrich Nuss Strümpfelbach |

20 years of the Federal Republic of Germany 1949–1969 |

1970-1987 | July 1, 1973 |

|

Kurt Schumacher (SPD) (1895–1952) first opposition leader (SPD) |

|

Hans-Joachim Dobler Walda |

30 years of the Federal Republic of Germany 1949–1979 |

1979-1993 | May 21, 1979 |

|

Ludwig Erhard (CDU) (1897–1977) Federal Minister of Economics, Federal Chancellor (1963–1966) |

|

Franz Müller Munich |

40 years of the Deutsche Mark 1948–1988 |

1988-2001 | June 20, 1988 |

|

Franz Josef Strauss (CSU) (1915–1988) Federal Minister, Bavarian Prime Minister |

|

Erich Ott Munich |

40 years of the Federal Republic of Germany 1949–1989 |

1990-2001 | October 9, 1990 |

|

Willy Brandt (SPD) (1913–1992) Federal Chancellor (1969–1974) |

|

Hubert Klinkel Würzburg |

45 years of the Federal Republic of Germany 1949–1994 |

1994-2001 | July 19, 1994 |

The 2 DM coins since 1958 thus differ from the other course coins: Similar to commemorative coins, they were issued for a special occasion and bear the head portrait of a famous person. From 1973 to 2001, large numbers of various 2 DM coins were also in circulation for a longer period of time.

5 DM coin

A competition was held for the design of the DM 5 coin in which 685 suggestions were submitted. 30 drafts were submitted to the Federal Cabinet on February 22, 1951 . Of these, Albert Holl from Schwäbisch Gmünd, Louis Robert Lippl , professor at the Technical University of Munich , and Franz Holz from Mainz were shortlisted. On May 8th the final decision was made in favor of Albert Holl.

The coin originally consisted of an alloy with 62.5% silver and 37.5% copper. Than silver speculation mid-1974 the price of silver per troy ounce temporarily (about 31 g) at about 6 US dollars rose (at an exchange rate of around 2.50 DM corresponding to 15 DM), the value of the metal approached the nominal value of the 5-mark piece . This could have made it worthwhile to melt down the coins (according to the Gresham-Copernican law from the 16th century). Then the production and issue of the coins would have been a losing business. In 1975 the old 5 DM coin was therefore taken out of circulation and replaced by a new coin made from Magnimat with a more modern depiction of the federal eagle.

In 1979, the exchange was discussed in the two-part television series Das Ding . At that time the price of silver had risen so much that the material value of the already minted silver commemorative coin “Otto Hahn” was actually well above the face value of 5 marks; the coins were therefore melted down to a few copies before they were issued. The subsequent re-minting and all subsequent commemorative coins with this face value no longer had any silver content.

All 5 DM circulation coins, like the 2 DM coins, bore the edge inscription “ Unity and Law and Freedom ”. The positioning (beginning of the text) and the orientation (correctly readable or upside down) of this imprint are not uniform due to the manufacturing process.

Nicknames

Nicknames (sometimes regional) were used for individual coins. The 10-pfennig coin was often called “ Groschen ” in colloquial language , and the 5-pfennig coin was sometimes called “sixes”. 1- and 2-pfennig coins were sometimes referred to as "Indian money" (possibly because of their brownish-red color). The 5 DM coins of the first issue up to 1975 were also called "silver eagle" due to the material used and the motif.

Regionally, the designation " Heiermann " was widespread in north and west Germany for the 5 DM coin . In Bavaria, the pfennig coins from a value of 5 pfennigs were provided with the Bavarian diminutive suffix "-erl" and were called "Fünferl", "Zehnerl" and "Fuchzgerl" (= "fifties") according to their face values. The 2 DM coin was often referred to as the "gusset". Many of the designations used in Bavaria for DM coins have now been transferred to euro coins with corresponding denominations; d. In other words, a ten is now a coin worth 10 euro cents, the gusset is now a 2 euro coin.

Rare course coins

The following list gives an overview of the rarest regular coins per denomination with the highest collector's value in freshly minted (ST) quality . In some cases, significantly higher prices are achieved for coins with a PP grade, and significantly lower prices for circulated coins.

- 1 pfennig coin from 1948 from Karlsruhe (G) approx. 90 euros

- 2-pfennig coin from 1950 from Karlsruhe (G) approx. 90 euros

- 5 Pfennig coin from 1967 from Karlsruhe (G) approx. 80 euros

- 10 Pfennig coin from 1967 from Karlsruhe (G) approx. 90 euros

- 50-pfennig coin from 1950 from Karlsruhe (G) with the inscription "BANK DEUTSCHER LÄNDER" approx. 1,800 euros (see above)

- 50 Pfennig coin from 1966 from Hamburg (J) and from 1995 from Stuttgart (F) and Karlsruhe (G) approx. 100 euros

- 1 DM coin from 1954 from Stuttgart (F) approx. 1,000 euros and from Karlsruhe (G) from 1954 approx. 1,600 euros and 1955 approx. 1,500 euros

- 2 DM coin "ears of corn" from 1951 from Karlsruhe (G) approx. 300 euros

- 2 DM coin "Max Planck" from 1959 from Munich (D) approx. 300 euros and from Stuttgart (F) approx. 400 euros

- 5 DM coin "Silver" from 1958 from Hamburg (J) approx. 4,500 euros

- 5 DM coin "Magnimat" from 1995, all mints approx. 50 euros

In addition, there are still rare misprints and samples, some of which are traded much higher.

Commemorative coins

In addition to the course coins , commemorative and special coins were also minted. Although they had legal tender status, they were very rare in everyday life.

The first D-Mark commemorative coin was issued on September 11, 1953 for the 100th anniversary of the Germanic Museum in Nuremberg. The coin had the same technical data as the 5 DM currency coin in circulation at the time. With a circulation of 200,000 pieces - of which only 1,240 in mirror finish ( PP ) - it reaches a value of up to 3600 euros for collectors. A total of 28 different motifs were published between 1953 and 1979.

After Munich was awarded the contract to host the 1972 Summer Olympics , the first DM 10 commemorative coin was issued on January 26, 1970; The picture was the spiral of rays , the logo of the games. By 1972, a total of five different motifs in connection with the Olympic Games were published. The increase in the first motif (spiral of rays) also led to a change in the legend: Since the games are each awarded to a city and not to a country, the original text “SPIELE DER XX. 1972 OLYMPICS IN GERMANY "changed to" ... IN MUNICH ". For the first time, all West German mints of the time were commissioned to produce the Olympic coins - previously all coins in an issue were minted by one institution. The coins consisted of 62.5 percent fine silver and 37.5 percent copper. They had a mass of 15.5 grams and a diameter of 32.5 millimeters.

After the 5-mark coin was exchanged for a Magnimat version as early as 1975 due to the high price of silver, silver was also dispensed with in commemorative coins from 1980. In 1979 the price of silver had soared to almost $ 50. For the coin issued on September 24, 1980 for Otto Hahn 's 100th birthday , the silver value of 7.21 DM would have been above the face value of 5 DM. Since then, all 5 DM coins have been minted from copper-nickel. 14 further motifs followed from 1980 to 1986. The last time a 5 DM commemorative coin was issued on October 22, 1986 on the 200th anniversary of Frederick the Great's death .

For the 750th anniversary of Berlin , the 10 DM commemorative coins were revived on April 30, 1987. The coin specifications corresponded to the Olympic coins. In 1998 the silver content (with the same diameter and same mass) was increased to 92.5 percent. Up to the introduction of the euro, 10 DM coins were issued on a total of 36 occasions .

On July 26, 2001, the Deutsche Bundesbank issued the last edition of the Deutsche Mark on the basis of the authorization by the law on the minting of a 1 DM gold coin and the establishment of the “Money and Currency” foundation of December 27, 2000. The coin is made of 999 fine gold and has the same appearance as the last 1 DM coin issued, with the difference that the inscription on the face is not "Federal Republic of Germany" but "Deutsche Bundesbank". The coin was issued with an edition of one million pieces at an issue price of DM 250. It is the only gold coin with the currency denomination Deutsche Mark.

Banknotes

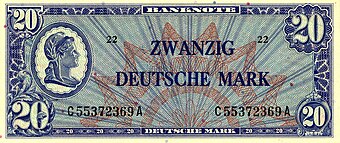

First series (1948)

The first series of banknotes was printed in the USA and was shipped to Bremerhaven in the spring of 1948 in the top secret operation "Bird Dog" . The 23,000 steel boxes with the new money were taken to Frankfurt by truck . The banknotes were then issued with the currency reform on June 20, 1948 by the Bank of German States under the sovereignty of the Western Allies . The design of the notes was very much based on the US dollar; even figures from American railroad stocks were used. There is no information about the issuing institution and no signature. The place of issue is also missing, so that, in the event of an agreement with the Soviet Union , a common currency would still have been possible throughout Germany.

Only banknotes from ½ Mark were available for the currency reform. Coins were not issued until 1949. In order to ensure the supply of small change to the population and the trade, the coins and banknotes still in circulation up to an amount of one Reichsmark could be used for a transitional period at a tenth of their face value. Therefore, it was initially possible to dispense with banknotes for amounts of less than 50 pfennigs.

Within the first series there were two different editions of the 20 and 50 DM notes.

On June 24, 1948, the area of validity of the Deutsche Mark (West) was extended to the three western sectors of Berlin . These banknotes were stamped and / or perforated with a “B”. Colloquially, these notes were therefore called "bear marrow".

| Face value | front | back | Dimensions | called to |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ½ DM | 112 mm × 67 mm | April 30, 1950 | ||

| 1 DM | 112 mm × 67 mm | February 28, 1957 | ||

| 2 DM | 112 mm × 67 mm | February 28, 1957 | ||

| 5 DM | 112 mm × 67 mm | May 31, 1950 | ||

| 10 DM |

Illustration of an allegorical group (symbol of work, justice and construction) |

141 mm × 67 mm | July 31, 1966 | |

| 20 DM | 146 mm × 67 mm | January 31, 1964 | ||

| 156 mm × 67 mm | May 3, 1949 | |||

| 50 DM | 151 mm × 67 mm | May 15, 1962 | ||

| 156 mm × 67 mm | July 31, 1949 | |||

| 100 DM | 156 mm × 67 mm | June 15, 1956 |

The notes in this series had no watermarks and, apart from guilloches and colored particles scattered into the paper, had no other security features .

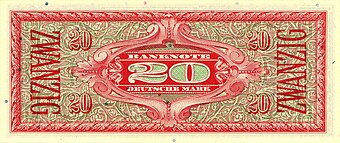

Second series Bank of German Lands (1948)

The second series was also issued in stages from August 20, 1948 by the Bank deutscher Länder and bore the imprint "Bank deutscher Länder" instead of "Banknote" on the front. The 10 and 20 DM notes are very similar to those of the first series. The notes of 5, 50 and 100 marks were designed by Max Bittrof . The banknotes were made of less durable paper and were printed in England, France and the USA. In 1955, Bundesdruckerei received the order to print the 5 DM banknote, followed by the 50 mark note from 1959.

| Face value | front | back | Dimensions | First edition | called to |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 5 pf | 60 mm × 40 mm | August 20, 1948 | October 31, 1950 | ||

| 10 pf | 60 mm × 40 mm | August 20, 1948 | September 30, 1950 | ||

| 5 DM |

The kidnapping of the Europa |

120 mm × 60 mm | March 22, 1950 | July 31, 1966 | |

| 10 DM |

Allegorical group : symbol of work, justice and construction |

141 mm × 67 mm | December 13, 1951 | July 31, 1966 | |

| 20 DM | 146 mm × 67 mm | December 1952 | January 31, 1964 | ||

| 50 DM |

The Nuremberg councilor and businessman Hans Imhof or the Nuremberg patrician Willibald Pirckheimer (controversial) based on a painting by Albrecht Dürer |

The same head portrait as on the front as well as motifs from port life |

150 mm × 75 mm | September 18, 1951 | July 31, 1965 |

| 100 DM |

The Nuremberg councilor Muffel von Eschenau after a painting by Albrecht Dürer |

The same head portrait as on the front as well as the old Nuremberg cityscape |

160 mm × 80 mm | May 16, 1951 | July 31, 1965 |

All notes in this series had guilloches as security features . In addition, the 5 and 10 pfennig as well as the 5 and 50 DM notes each had a watermark . The 5 DM note also had a security thread stored in it .

The 5, 50 and 100 DM banknotes bore the threat of punishment on the back: "Anyone who copies or falsifies or falsifies or falsifies banknotes and markets them will not be punished for less than two years", which was also based on the earlier Reichsmark - Banknotes was attached.

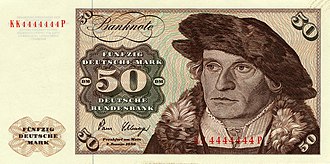

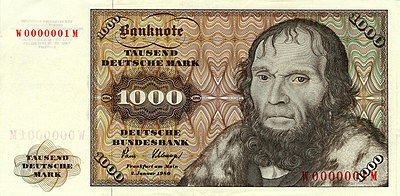

Third series of paintings series BBk I (1961)

The third series of banknotes was issued from 1961 to the early 1990s. The plans for the new banknote series were drawn up as early as 1957 when the Bank deutscher Länder was converted to the Deutsche Bundesbank, because the information "Bank deutscher Länder" printed on the previous series was no longer correct. As the first series to be published by the Bundesbank, it bears the internal name “BBk I”.

Compared to the later banknotes, the banknotes of the previous series had a very short lifespan, as they were made of paper that was not very durable. If previously damaged notes could still be replaced from reserve stocks, this stock was also running out, so that a reprint was necessary for this reason.

Typical security features at that time were guilloches , a multi-level head watermark and a security thread. Note numbers fluorescent under UV light and green, yellow, and blue fluorescent fibers embedded in the paper were found in most banknotes; however, there were also some specimens in circulation without these characteristics. The paper of the banknotes was tinted green (5 and 20 marks), bluish (10 and 100 marks) or yellowish (other banknotes). From 1977 the banknotes were given the M feature . For this machine-readable feature, a colorless inorganic oxide mixture was applied to the security thread. Banknotes that are secured against forgery in this way were designated internally as BBk Ia . All banknotes of the third series bore the threat of punishment for counterfeiting and forgery on the reverse.

The 500 million new banknotes were printed exclusively in Germany, about half each - measured by the number of banknotes, not the number of values - in Berlin at the Bundesdruckerei and in Munich at the private printing company Giesecke & Devrient . In 1960, the printing of the first 20-D-Mark bills started, later the 100 and 1000-Mark bills were also printed by Giesecke & Devrient. The printing costs of around 50 million marks were financed by the profits of the Bundesbank. In total, a volume of cash with a nominal value of around 20 billion marks had to be exchanged.

Although urgently requested by trade, the Bundesbank hesitated to introduce the new thousand-mark note in order to counteract rumors of impending inflation. However, the circulation of the thousand-mark note increased steadily over the years. In the year of issue 1964 there were 640,000 banknotes, in 1974 4.5 million and a further ten years later 19.4 million.

There were a total of five issues of this banknote series. The first edition was dated January 2, 1960 and was signed by the then President and Vice President of the Bundesbank, Karl Blessing and Heinrich Troeger . After the change at the head of the Bundesbank, the second edition appeared with the date January 2, 1970. At the same time, in the threat of punishment on the back, the word “ prison ” was replaced by “ custodial sentence ”, since the prison sentence was abolished in the course of the major criminal law reform in 1969 was. The signatures were from the new Bundesbank leadership, Karl Klasen and Otmar Emminger . On June 1, 1977 Emminger took over the office of President, and Karl Otto Pöhl succeeded as Vice President. The banknotes have had the M feature since this issue and are referred to as BBk Ia. The date of issue was last changed on January 2, 1980. Pöhl was now president and Helmut Schlesinger his deputy. An additional copyright notice was later printed on the back of the banknotes . However, this change did not result in any adjustment to the issue date.

The banknote series was suspended on June 30, 1995, almost three years after the successor series had been fully launched.

draft

Head portraits, inscriptions and the format of the banknotes were determined by the Bundesbank. Since protection against forgery was paramount, head portraits that were difficult to imitate from old, culturally and historically recognized paintings were used. When it comes to the basic colors, the Bundesbank followed the previous series. For the new banknote values of 500 and 1000 marks, red and brown were selected. These two note values are the only ones in this series to have the banknote numbers on the back.

For the further design, namely the selection of motifs for the back and the ornamental design, the Bundesbank announced a competition and invited ten graphic artists who had already had experience in designing banknotes and postage stamps. The winning design was selected in early 1959 with the participation of the then Federal President Theodor Heuss . The participants were:

- His designs were used for the BBK I series.

- His designs were used for the BBK II series (replacement series).

- His designs were used for the BBK IIa series (replacement series for Berlin).

René Binder

- Although these designs were not realized, graphic implementations of this series became known in an exhibition.

- His designs are vaguely reminiscent of the trillion bills from 1924, insofar as they show the portrait within a rectangular window on the right.

- His designs also show the portraits in a rectangle; curved lines on the front of the note break up the overly "square" impression. As a watermark, he was probably the only one to suggest not a head portrait, but an eagle.

- The notes he designed have a watercolor-like effect, with round curved lines predominating.

- His designs show the portraits in a round medallion ; the value is centered on the left. The backs of the higher values show motifs like an eagle.

Alfred Goldammer

- His designs are completely dominated by circles and rounded lines.

Leon Schell

- On the back of the only previously known design for 50 DM is a medieval trading scene.

The winner was the Swiss Hermann Eidenbenz, who lived in Hamburg at the time. Some of his proposals to depict the painting Knight, Death and the Devil by Albrecht Dürer on the reverse of the thousand-mark note were rejected by the Bundesbank. Eidenbenz later said that the gentlemen did not like it. Instead, the reverse of the note showed Limburg Cathedral , engraved by the Munich engraver and graphic artist Sebastian Sailer . Other changes concern, for example, the 5 DM note, which featured an oak instead of an oak leaf, and the 50 DM note, which was originally intended to show a German city silhouette.

Illustrations and dimensions

| Face value | front | back | Dimensions | First edition |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 5 DM |

Young Venetian (based on a painting by Albrecht Dürer , Kunsthistorisches Museum Vienna) |

A branch with oak leaves and acorns symbolizes German nature |

120 mm × 60 mm | May 6, 1963 |

| 10 DM |

Portrait of a young man (according to an older view based on a painting by Albrecht Dürer or Anton Neupauer , according to more recent research based on an early portrait by Lucas Cranach the Elder , which is in private ownership of the Landgrave of Hesse and is not open to the public) |

The sailing training ship Gorch Fock of the Bark type symbolizes the German cosmopolitanism |

130 mm × 65 mm | October 21, 1963 |

| 20 DM |

The Nuremberg patrician and merchant wife Elsbeth Tucher (based on a painting by Albrecht Dürer, on display in the Old Masters Picture Gallery in Wilhelmshöhe Palace in Kassel ) |

A violin and a clarinet symbolize the world of German music |

140 mm × 70 mm | February 10, 1961 |

| 50 DM |

Portrait of a man (after the painting Portrait of Hans Urmiller with his son by Barthel Beham , around 1525; the painting hangs in the Städel Museum in Frankfurt ) |

The Holsten Gate in Lübeck symbolizes German civic pride |

150 mm × 75 mm | June 18, 1962 |

| 100 DM |

The cosmographer Sebastian Münster (after a painting by Christoph Amberger , Gemäldegalerie in Berlin ) |

The eagle with outspread wings ( federal eagle ) symbolizes the state consciousness of the Germans |

160 mm × 80 mm | February 26, 1962 |

| 500 DM |

Male portrait (based on the painting Portrait of a Beardless Man by Hans Maler zu Schwaz , Kunsthistorisches Museum Vienna) |

The Burg Eltz in Rhineland-Palatinate symbolizes the German chivalry |

170 mm × 85 mm | April 26, 1965 |

| 1000 DM |

Male portrait (based on a painting by Lucas Cranach the Elder , Royal Museums of Fine Arts in Brussels ), considered for a long time as the Magdeburg canon Johannes Scheyring , but possibly more the mathematician and astronomer Johannes Schöner . |

The Limburg Cathedral symbolizes Romanesque architecture in Germany |

180 mm × 90 mm | July 27, 1964 |

Replacement series (BBk II) and federal cash receipts

In the event of a major disruption to the circulation of money that would have required the banknotes to be exchanged, the Bundesbank decided on January 20, 1959 to manufacture printing plates for reserve banknotes .

Despite the 30-year confidentiality period (expired in 2010), it was apparently no secret that a series of reserve banknotes existed; because the Bundesbank reported in its monthly report of November 1962 about the facts: “In addition, a shortened (i.e. limited to values of 10, 20, 50 and 100 DM) replacement series was compiled from the drafts of the Frankfurt graphic artist Max Bittrof , who wrote the notes for the Bank deutscher Länder for 5 DM - Europe with the bull - as well as 50 and 100 DM with portraits of Imhof and Muffel. ”In 1964 the replacement series was mentioned again. Four years later the press responded and some minor articles appeared in the newspapers. After the 30-year confidentiality period for the relevant Bundesbank files had expired in 2010, the details of this series became better known.

The Bundesbank had two series of replacement banknotes produced. One series was planned for West Germany and was given the internal name "BBk II" . The other series was intended for West Berlin and was internally called the "Berlin series" or "B series" . There were nominal values of 10, 20, 50 and 100 marks and an additional 5 marks for Berlin.

Two of the “losers” in the competition for the “BBk I circulation series” were selected to create the replacement series: Max Bittrof and Rudolf Gerhardt. Bittrof received the stipulation that the back of the series of replacement notes should be designed with pure ornamentation according to his design for the 50-mark note from the BBk I series.

The printing of the banknotes began in 1963 and lasted until 1974, as the amount of replacement notes had to be adjusted to the actual amount of banknotes in circulation. The notes of 20 and 100 marks were printed by the Bundesdruckerei in Berlin, the notes of 10 and 50 marks by the private banknote printing company Giesecke & Devrient . Almost 785 million banknotes with a total face value of around 29 billion marks (approx. 25 billion marks for West Germany and approx. 4 billion marks for West Berlin ) were produced in several tranches, and a good half of them from 1964 to 1988 in the top secret Bundesbank bunker in Cochem stored. The rest was stored in the federal bank vault in Frankfurt.

The Berlin series of BBk II by Gerhardt largely corresponded to the designs that the graphic artist had submitted for the BBk I competition. This series was designed exclusively in Berlin, printed at the Bundesdruckerei and stored at the regional central bank there. The word Berlin does not appear on these banknotes, however; Frankfurt am Main was also named as the place of issue on this series. There were a total of three print jobs from the Bundesbank to Bundesdruckerei.

In 1967 the Bundesdruckerei also produced the federal cash slips on behalf of the Federal Ministry of Finance as an additional means of replacement. The federal treasury bills were only available in small denominations (5, 10 and 50 pfennigs and 1 and 2 DM); they thus represented a substitute for coins. Especially in times of crisis, the material value of coins often exceeds their face value and leads to the coins being melted down or being hoarded by the population. The design was kept very simple as there were no portraits or other images. These banknotes were also stored in the Bundesbank bunker in Cochem.

There is no information about the exact reasons for creating the banknotes. Officially, the aim was to “generally remedy any shortage of change that might arise” and “to be able to quickly counter forgeries on a large scale [...]”; however, due to BBk II's own Berlin series and under the impression of the Cold War , a political background is also assumed.

The Bundesbank and the Ministry of Finance decided in 1988 to destroy the replacement money because the security features were no longer sufficient to effectively prevent counterfeiting. Thus there was no longer any use, and cash was no longer so urgently necessary due to electronic payments.

However, some of the banknotes were stolen from the commissioned private disposal companies, so that to this day some notes are still in the possession of collectors. In the case of public auctions, however, the Bundesbank intervenes by declaring the federal cash receipts as stolen goods and having them confiscated.

BBk II for West Germany

The drafts for the banknotes came from the freelance graphic artist Max Bittrof . The watermark was similar to the head portrait, but not the same. Fluorescent fibers were only incorporated into the paper of the 100 DM note. All banknotes were dated July 1, 1960 and had a security thread.

| Face value | front | back | Dimensions | number of pieces |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 10 DM | 130 mm × 65 mm | 186,480,000 | ||

| 20 DM | 140 mm × 70 mm | 199,980,000 | ||

| 50 DM | 150 mm × 75 mm | 179,040,000 | ||

| 100 DM | 160 mm × 80 mm | 104,580,000 |

BBk II for West Berlin

The series for West Berlin came from Rudolf Gerhardt, a graphic artist for Bundesdruckerei. This series of banknotes did not contain any security thread or fluorescent fibers. Instead of a head watermark, an area watermark made from the letters "BBk" was used. The notes were dated July 1, 1963.

| Face value | front | back | Dimensions | number of pieces |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 5 DM | 120 mm × 60 mm | 20,500,000 | ||

| 10 DM | 130 mm × 65 mm | 24,500,000 | ||

| 20 DM | 140 mm × 70 mm | 25,900,000 | ||

| 50 DM | 150 mm × 75 mm | 25,500,000 | ||

| 100 DM | 160 mm × 80 mm | 18,500,000 |

Federal cash bills

Apart from the guilloches, the federal cash bills have no security features . In contrast to all other banknotes, the term “banknote” is missing on the federal cash slips. The "Deutsche Bundesbank" is also not named as the issuer, but - as with the circulation coins - the "Federal Republic of Germany", represented by the Ministry of Finance. Federal cash bills and substitute banknotes were held for wartime from 1960, but were never issued.

| Face value | front | back | Dimensions |

|---|---|---|---|

| 5 pfennigs | 60 mm × 40 mm | ||

| 10 pfennigs | 70 mm × 45 mm | ||

| 50 pfennigs | 80 mm × 50 mm | ||

| 1 DM | 90 mm × 55 mm | ||

| 2 DM | 100 mm × 60 mm |

Fourth series personality series BBk III (1990)

On March 19, 1981, the members of the Central Bank Council of the Deutsche Bundesbank decided to issue a new series of banknotes. It had become necessary because of technological advances that made counterfeiting old banknotes easier and easier. A new series would also be better suited for automatic payments. It was almost ten years before the first two banknote denominations were put into circulation on October 1, 1990. These were the 100 and 200 DM notes. The latter face value was newly introduced in this series of banknotes.

There were many decisions to be made when designing the banknotes and choosing the design elements. Portraits were defined as the main motif in the preliminary considerations for the new series. "Head portraits of personalities in German history from the fields of art, literature, music, business, science and technology should be chosen". In addition, the back should be related to the person depicted on the front. Furthermore, the basic colors of the note values should remain unchanged and the word banknote should appear in Gothic script on every note.

Person selection

A committee consisting of the historians Karl Otmar von Aretin , Knut Borchardt and Horst Fuhrmann was commissioned to determine the personalities who should appear on the banknotes. There were around 70 to 80 people to choose from. "Top personalities" (e.g. Goethe , Schiller , Dürer ) were omitted. Likewise, people were eliminated whose national affiliation was unclear or who could have meant a provocation in a denominational or political way (e.g. Martin Luther , Karl Marx ) or who had done their work primarily abroad, such as Jacques Offenbach .

When selecting the people, attention should be paid to a balance with regard to gender, religion, origin and field of work. If possible, three, but at least two, female characters should be represented in the series. However, the choice of female personalities was very limited. The aim was to show women who had created their own work and were not in the shadow of men close to them ( Charlotte von Stein , Charlotte von Kalb ). However, such women were very rare until the 19th century. Therefore, the committee first selected the female personalities, so that restrictions regarding the area of activity, origin or denomination did not have to be taken into account.

One of the specifications for the design was that the people, as seen from the viewer, should look to the left towards the center of the banknotes. This meant that the intended portraits for the five, ten, twenty, fifty and two hundred mark banknotes had to be mirrored. Since two people were to be depicted with the Brothers Grimm, the largest banknote was reserved for them due to the large amount of space required. Otherwise men and women should take turns. The rest of the assignment of person and grade value was random and does not represent any evaluation of the people.

Maria Sibylla Merian was originally intended for the 100 DM note and Clara Schumann for the 500 DM note. For the portrait of Maria Sibylla Merian, however, only an artistically inferior etching by Johann Rudolf Schellenberg was available, as doubts about the authenticity of the original model arose. That is why the Bundesbank organized a design competition to get a high-quality master copy from this etching that would later become the basis for the portrait on the banknote. Since the 100 DM note was to be one of the first to appear, people were swapped due to these difficulties.

Selection of the winning design

For the design competition, which ran from January 1 to June 30, 1987, four graphic designers were commissioned by the Bundesbank: Bundesdruckerei (represented by Rudolf Gerhardt, who had already designed the replacement banknotes (BBk-II) for West Berlin ), Ernst Jünger, Johann Müller and Adrian Arthur Senger. According to the judgment of a commission of experts consisting of historians, designers and graphic artists as well as a sociologist, only one series met the high expectations. However, this was too reminiscent of the Swiss franc , so that it was also out of the question. A new design competition that would have delayed the project by at least a year would actually have been necessary. However, since Bundesdruckerei wanted to submit two drafts, which the Bundesbank did not accept, the draft by the Bundesdruckerei's then chief graphic designer, Reinhold Gerstetter , was still unseen in the custody of the Bundesbank. After being examined by the committee, this draft was ultimately chosen as the basis for the new series of banknotes. The reviewers wrote: “The art expert committee is unanimously of the opinion that the design properties compiled here [...] largely meet the requirements [...]. In this sense, the art expert committee can recommend the Deutsche Bundesbank to make the drafts available as the basis for a new series of banknotes. "

Design of the front sides

The city maps on the front were an idea of Gerstetter. In some of his designs, striking modern buildings of the respective cities could be seen. However, the design by the city of Frankfurt led to the decision to only show historical buildings. The reason given was that the office towers of Deutsche Bank dominated the design and the Bundesbank should not be suspected of advertising a private company.

In 1988 it was now a matter of choosing the right city for each person. The draft of the graphic artist intended for Paul Ehrlich Bad Homburg vor der Höhe , the place where he died. However, his work mainly took place in Berlin and Frankfurt am Main. Gerstetter had planned Frankfurt for Clara Schumann, who spent the last years of her life there. After the decision to introduce the 5 DM note with the portrait of Bettina von Arnim, it quickly became clear that the city of Berlin would be depicted on it. Because each city should only appear once on the banknotes, Paul Ehrlich only considered Frankfurt. The city of Leipzig was later chosen for Clara Schumann because Leipzig was not only her place of birth, but also because she had her first major successes there.

Due to the events in 1989/1990 , the decision for Leipzig turned out to be a stroke of luck; because the banknote series was originally only intended for West Germany and West Berlin . But the new federal states were also represented with a city that also has a special symbolic meaning: This is where the first Monday demonstrations took place, which led to the dissolution of the GDR and the reunification of Germany .

Design of the back

Reinhold Gerstetter envisaged an illustration from the fairy tale Die Sterntaler as the central motif for the back of the 1000 Mark note . However, despite their extensive collection of fairy tales, the Brothers Grimm should not be reduced to fairy tales, as they have made a great contribution to the German language by publishing the German dictionary . The dictionary thus became the main motif, and the Sterntaler “wandered” into the Weißfeld region.

Great attention to detail was also applied to the design of the back. Even the background patterns are related to the person depicted on the front. In the fourth series, there was no longer any threat of punishment for counterfeiting banknotes.

- Background pattern on the back of banknotes

The five-mark note

Originally, as with the previous series, seven note values were planned for the new banknote series. However, the 5-DM note was to be given up in favor of a new 200-mark banknote coming into circulation. The number of DM 5 notes in circulation was only around five percent of the corresponding coins. By contrast, at the end of 1980 around 38 percent of all cash in circulation consisted of 100 DM notes. It was not until June 1987 that the members of the Central Bank Council decided to continue issuing a DM 5 note, thus expanding the series to eight denominations.

However, since the people for the other banknotes had already been determined, it was difficult to find a "suitable" one, because it was supposed to be a Catholic woman who could stand in a row with the personalities selected so far Lived until the beginning of the 20th century. Bettina von Arnim was the only woman who met these criteria, even though the subject of poetry and literature was taken up again with her (see Droste-Hülshoff) and her national assignment did not open up a new region.

The reverse of the first draft showed a Goethe monument designed by Bettina von Arnim. However, the banknote should not be turned into a Goethe banknote “through the back door” . After all, among other things, his signature was on the banknote that was ultimately realized. The second draft (with a wreath of flowers, as shown in her book Clemens Brentano's Spring Wreath) was, as it is said, discarded for aesthetic reasons. Since the series had meanwhile become an all-German series, the Brandenburg Gate appeared on the note , which was built and inaugurated during her lifetime. It was and is the symbol of German unity . This also made the five-mark note an all-German banknote.

Incidentally, the 1000 DM note was also adapted to the new political conditions, with the illustration of the Sterntaler becoming a secondary motif and placing Berlin and, indirectly, Leipzig at the center of the presentation.

Illustrations and dimensions

| Face value | front | back | measurements and weight | First edition |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 5 DM |

Bettina von Arnim (1785–1859), writer, Catholic; in the background a partial view of the Wiepersdorf estate managed by her husband and a cornucopia as a symbol of her diverse intellectual interests as well as historical buildings in Berlin. Original image: Painting by Achim von Arnim , private property. |

Brandenburg Gate (as a symbol of German unity) and signatures of important personalities from the time of Arnim against the background of an envelope |

122 mm × 62 mm approx. 0.68 g |

October 27, 1992 |

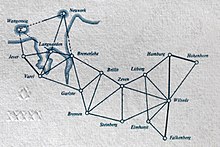

| 10 DM |

Carl Friedrich Gauß (1777–1855), mathematician , astronomer , geodesist and physicist , Lutheran; in the background building of the historical Göttingen , where Gauß worked as a professor, and a picture of the "Gaußschen bell curve" ( normal distribution ). Original image: Copy of a painting by Christian Albrecht Jensen from 1840, painted by Gottlieb Biermann in 1887, University Observatory Göttingen |

The vice-heliotrope invented by Carl Friedrich Gauß as well as a section of the triangular network of the triangulation of the Kingdom of Hanover carried out by Gauß , in which, among other things, this instrument was used. |

130 mm × 65 mm approx. 0.76 g |

April 16, 1991 |

| 20 DM |

Annette von Droste-Hülshoff (1797–1848), poet, Catholic; in the background historical buildings of the city of Meersburg , where she temporarily lived, as well as a laurel branch. Original image: Painting by Wilhelm Stiehl from 1820, Droste Museum, Meersburg |

A quill and a book as a reference to the novella Die Judenbuche as well as a stylized open book |

138 mm × 68 mm approx. 0.84 g |

March 30, 1992 |

| 50 DM |

Balthasar Neumann (1687–1753), Baroque builder , Catholic; in the background views of historical buildings from Würzburg and a proportional circle. Original image: Painting by Marcus Friedrich Kleinert from 1727, Mainfränkisches Museum, Würzburg |

Partial views of Neumann's buildings, including the staircase of the Würzburg Residence , a longitudinal section of the Neresheim Abbey Church and the floor plan of the Kitzinger Kreuzkapelle |

146 mm × 71 mm approx. 0.93 g |

September 30, 1991 with kinegram : February 3, 1998 |

| 100 DM |

Clara Schumann (1819–1896), composer and pianist, Lutheran; in the background historical buildings from Leipzig and a stylized lyre. Original image: Unknown master, ivory miniature around 1840 (signed QL), private property |

A concert grand piano and the Hoch Conservatory in Frankfurt (Clara Schumann's place of work) as well as a swinging tuning fork |

154 mm × 74 mm approx. 1.03 g |

October 1, 1990 with kinegram: August 1, 1997 |

| 200 DM |

Paul Ehrlich (1854–1915), physician and serologist, Jewish; in the background historical buildings in Frankfurt am Main , an X-ray structure analysis and a stylized molecular model of the syphilis drug Salvarsan, which he discovered. Original image: Photograph on the occasion of his 60th birthday, private collection |

A microscope as well as abstract representations of viruses and bacteria, a staff of Aesculapius and a stylized retort |

162 mm × 77 mm approx. 1.12 g |

October 1, 1990 with kinegram: August 1, 1997 |

| 500 DM |

Maria Sibylla Merian (1647–1717), natural scientist, painter and engraver, Lutheran; in the background the buildings of historic Nuremberg and a stylized wasp. Original image: Drawing made in the Bundesdruckerei Berlin after an etching by JR Schellenberg |

Illustration of a dandelion, as well as a caterpillar and a butterfly of the gorse-straightener from her book Der Raupen Wunderlich Umwanderung und strange flower food , published in 1679 (plate 8). |

170 mm × 80 mm approx. 1.22 g |

October 27, 1992 |

| 1000 DM |

Wilhelm (1786–1859) and Jacob (1785–1863) Grimm , linguists and collector of German linguistic and cultural assets, reformed; in the background historical buildings in Kassel and a letter "A" as a symbol for the German dictionary created by the Grimms . Original picture: Painting by Elisabeth Jerichau from 1855, Staatliche Museen Prussischer Kulturbesitz, Nationalgalerie Berlin. |

First volume (A – Biermolke) of the German Dictionary (Leipzig 1854) open on the title page , including the first eight lines of the manuscript on the subject of freedom , the Royal Library Berlin , the place where the Grimms worked from 1840, together with the French Cathedral on Gendarmenmarkt and an illustration to the fairy tale Die Sterntaler . |

178 mm × 83 mm approx. 1.33 g |

October 27, 1992 |

Technical design and security features

The paper of the banknote was made of cotton and was dyed lightly in the base color of the banknote: enough for the human eye to see this color, but not so strong that color copiers could reliably reproduce this color. In addition, the paper was mixed with yellow, blue and red fluorescent fibers that were visible under UV light. The banknote paper had a thickness of 100 μm and a weight per unit area of 90 g / m² (in each case ± 5% tolerance). The banknote number was printed in fluorescent color on the face of the banknote in the upper left and lower right. It contained an individual check digit, which was calculated using dihedral groups .

As with the BBk I series, the notes had the mirrored portrait of the banknote as a watermark . Newly added security features were the note value watermark, the see-through register and an aluminum-coated security thread embedded in the paper - printed with the value of the banknote , which was partially visible on the front (so-called "window thread"). Also were in many places microprinting , intaglio printing and moiréerzeugende structures. The tilting effect , which shows the letters “DM” below the vertical value number on the side, when the banknote is tilted at a certain angle , was difficult to see . The optically variable color was only used on the 500 and 1000 D-Mark banknotes at the bottom of the large value number on the front.

- Security features newly introduced with the BBk III series (selection)

There were also other security features that could only be recognized with the help of technical aids. This included a watermark barcode, magnetic pigments in certain printing inks and certain printed images under UV or infrared light.

As in the previous series, half of the banknotes were produced by the Bundesdruckerei in Berlin and the private printing company Giesecke & Devrient in Munich. According to the private printing company, the production of a banknote cost between 10 and 20 pfennigs.

The placing on the market

According to the Bundesbank, the technical introduction of the new series went smoothly. In order to counter rumors and fears of a currency reform in advance , the Bundesbank issued a press release on March 24, 1988 for the first time about the new banknote series. On April 17, 1989, the series was presented to the public for the first time.

A good six months before the planned introduction date, the Bundesbank started a large-scale campaign in the print media for 15 million marks to inform the population about the new image. Great emphasis was placed on the description of the new security features. There were also brochures that were on display at banks and savings banks. In August 1990, a corresponding leaflet was sent to a large part of the population as an attachment to the telephone bill.

But there was also criticism. By highlighting the (new) security features, the population got the impression that the banknotes could not be forged. As a result, the necessary care was not taken when handling the new banknotes. Supported by this behavior and by the increasing spread of affordable scanners and color printers , there was an accumulation of false banknotes. The Federal Criminal Police Office (BKA) and the State Criminal Police Office criticized the fact that their technicians and counterfeit money experts had hardly been listened to.

After the introduction of the DM 10 note in April 1991 as the third note in the new series, there were occasional media reports about mix-ups with the DM 100 note due to the similarity of colors (bluish violet vs. reddish blue). The Bundesbank saw no need for action, however, as there were occasional mix-ups when the BBk I series was introduced, but these subsided after the population had got used to the notes and a minimum of care was taken in payment transactions.

Criticism also came from the German Association for the Blind and Visually Impaired . In a letter to the Deutsche Bundesbank, it was criticized that the tactile markings could only be felt as long as the banknote had hardly been in circulation, and that the differences in length between the different note values of 8 mm were too small to be able to distinguish the banknotes.

Some supposed flaws were also discovered on the banknotes. The grand piano in the Robert Schumann House in Zwickau has two pedals. On the other hand, four are depicted on the banknote. To explain it, it is said that this grand piano should not be shown, but only a musical instrument from that time. The designer Reinhold Gerstetter later explained that he could not exactly see the number of pedals in the pictures available to him. The "spelling error" on the card in the white field on the back of the 10-mark note Wangeroog (e) was also frequently criticized. Research by the Bundesbank revealed that the spelling of the island's name changed frequently and that it was spelled without an "e" at the time of Gauss.

Improvement of the security features (BBk IIIa)

From August 1, 1997, banknotes to the value of 100 and 200 marks were issued with revised security features, as they were the most frequently forged ones. In February 1998 a new 50 DM note was also put into circulation. These banknotes were given the internal series designation “BBk IIIa”. The most noticeable changes are the kinegram on the left and the pearlescent strip on the right side of the front. The “tipping effect” has also been improved. In addition, the banknotes are slightly different in color from the old notes; they look a bit more pastel colored and the lines are not quite as sharp. The background patterns (especially on the back) have also been changed. While motifs related to the person depicted were seen there before, circular patterns can now be seen. The new notes also feature the EURion constellation , which is intended to prevent scanners and copiers from being reproduced.

- New security features in the BBk IIIa series

Front of the 100-mark note BBk IIIa with EURion constellation

With the introduction of the euro , the Deutsche Mark and with it this fourth series of banknotes lost their legal tender status at the end of December 31, 2001.

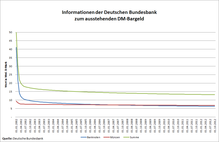

Development of the currency in circulation

The currency in circulation has grown steadily in the 53 years in which the Deutsche Mark was issued. It was not until 1998 that the annual average of cash in circulation fell below the previous year's level.

In 1950 the amount of cash issued was DM 7.8 billion, in 1955 it was already DM 15.5 billion, and in 2000 it reached DM 244.8 billion. This increased the amount of cash more than 30 times. During this period, the national product rose in nominal terms by 38 times (eight times in real terms). As a result, the cash ratio (the ratio between the amount of cash in circulation and the national product) has declined slightly over the years. Since the German collector coins had very high denominations of 5 and 10 DM respectively, their share of the coin circulation at the end of 2000 was around 25%.

Since the 1970s, the amount of DM cash has increased steadily abroad, on the one hand through guest workers who took the money back to their old homeland, and on the other hand through the Germans' willingness to travel. DM cash was also brought abroad in order to invest it profitably there. The amount of DM cash in circulation abroad is not statistically recorded, but a study by the Bundesbank assumes "that at the end of 1994 between 30% and 40% of the DM stock could have been abroad".

Since the federal government announced in October 1987 that it would introduce a withholding tax on interest income, the demand for cash has risen sharply. The 500 and 1000 mark bills were particularly popular. It wasn't until April 1989 that these plans were abandoned that demand fell again.

The introduction of the D-Mark in the former GDR did not lead to a significant increase in the amount of cash in circulation, as the exchange was mostly cashless. Until July 6, 1990, GDR money had to be deposited into an account. The credit could then be used in D-Marks. The GDR pfennig coins could still be used at the rate of 1: 1 until July 1, 1991, as not enough coins could be made available immediately. The need for banknotes could be met from the Bundesbank's existing reserves.

The largest share, both in terms of value and number, of the paper money issued in 2000 was the 100 DM note. 37.1% of the banknotes were 100-mark notes, the value of which accounted for 38.9% of the currency in circulation. The second largest share in terms of value was due to the high face value with 34% of the 1000 DM note before the 500 mark note with 10.1%. In terms of numbers, the 10-mark note with 20.7% was ahead of the 20-mark note with 17.6%.

- Cash Flow Chart (2000)

Shortly before the introduction of euro cash on January 1, 2002, the national cash holdings in Germany fell faster than in any other country in the monetary union. Mainly the large DM banknotes found their way back from abroad. At the end of 2001, at 162.2 billion marks, only 60% of the previous year's figure was in circulation.

When planning the introduction of the euro, the Bundesbank assumed a "shrinkage rate" (ie the proportion of cash that is not exchanged) for coins of more than 40%. Thus a total of around 28.5 billion coins with a face value of around 9.5 billion marks had to be collected and disposed of. 2.6 billion pieces with a value of around 260 billion marks were expected for banknotes.

With the introduction of euro cash, the coins and banknotes of the Deutsche Mark lost their legal tender status at the end of December 31, 2001 . The Deutsche Bundesbank has been exchanging DM banknotes (with the exception of the 50 Mark BdL Note II (green), issue date 1948) and coins (with the exception of the 2 DM coin, 1st issue 1951) since January 1, 2002 " Ears of corn ”) at the fixed exchange rate in euro banknotes and euro coins according to § 1 DMBeEndG free of charge and for an unlimited period.

As the table below shows, a few years after the introduction of the euro, considerable quantities of DM coins and notes had not been exchanged. As of the end of June 2016, their total value was around 12.76 billion marks, which corresponds to 6.52 billion euros. With 72 million pieces, the largest share of the non-exchanged banknotes are 10 DM notes. The front runner among coins is the pfennig with 9.7 billion pieces. According to the Bundesbank, coins and notes worth around 100 million marks are exchanged every year. 167.3 million banknotes and 23.5 billion coins have not yet been returned.

| end of year | Total value | Share compared to 2000 |

Coins | Share compared to 2000 |

Banknotes | Share compared to 2000 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2000 | 274.1 billion DM | 100.00% | 12.1 billion DM | 100.00% | 262 billion DM | 100.00% |

| 2005 | 14.71 billion DM | 5.37% | 7.22 billion DM | 59.67% | 7.49 billion DM | 2.86% |

| 2010 | 13.44 billion DM | 4.90% | 6.93 billion DM | 57.27% | 6.51 billion DM | 2.48% |

| 2015 | 12.82 billion DM | 4.68% | 6.77 billion DM | 55.95% | 6.05 billion DM | 2.31% |

| For a detailed list see source | ||||||

After the Bundesbank has withdrawn the exchanged coins and notes, they are destroyed. The banknotes are shredded; the coins are devalued by deformation, melted down and sold as raw material to other countries whose coins are made of the same alloy.

Fakes

The German mark was the second most common counterfeit currency in the world; only the US dollar was counterfeited more often. In 1996, according to Interpol, counterfeit banknotes of the Deutsche Mark with a nominal value of 40 million marks were seized worldwide. In the same year, 25,769 counterfeit banknotes were discovered at the Bundesbank. The main share was in the 100 and 200 mark notes (see graphic). Smaller bills have a lower yield and larger bills are more difficult to circulate because they are viewed more critically.

The beginnings

The first forgeries began to appear shortly after the first Deutsche Mark coins and banknotes were issued. As early as August 15, 1949, the Weser-Kurier was looking for a 31-year-old counterfeiter, then known as a "counterfeiter", who, together with an accomplice, produced 20 DM banknotes worth 70,000 DM and put them on the market tried. 160,000 counterfeit banknotes were discovered in 1949 and 138,000 in 1950.

In 1962, three men from southern Germany produced over 11,000 fake 50-mark bills, but were unable to get any of them into circulation until they were arrested. A year later, two Hamburgers were also unable to put their counterfeit 10 DM notes worth 200,000 DM into circulation. Because the banknotes were produced at night in artificial light, the colors could not be matched exactly, so that these banknotes had a distinct yellow cast. In the nine years before, almost 6,000 counterfeit banknotes with a face value of almost DM 220,000 were seized in Germany.

Karlsruhe coin scandal and the flower rembrandt

The Karlsruhe coin scandal that was uncovered in 1974 was not about counterfeit money, but about illegal real money . Three employees of the local mint minted rare coins with a collector's value of around DM 500,000 at the time for their own account and brought them into circulation. You were sentenced to prison terms at the second instance in June 1978, two of whom were suspended on probation. The court was of the opinion that coins that are produced in a state mint on original blanks with original stamps, but without a state commission, are to be classified as counterfeit.

In 1975 Günter Hopfinger achieved particular fame. Hopfinger, who later became known as "Blumenrembrandt", drew the 1,000 DM notes of the third series with ink in just eight hours on ordinary typewriter paper. How many of these notes he put into circulation is not entirely clear. Depending on the source, 11, 35 or 80 banknotes are named. Hopfinger was sentenced to four years in prison. Later, the counterfeit banknotes were three times as expensive as the originals. The criminal police later produced an educational film about this case, and this case also served as a model for the crime scene episode “ Stuttgart Blossoms ”.

In 1976 the banknotes in circulation amounted to 58 billion marks. Of this, 275,000 marks consisted of 2,700 counterfeit banknotes.

The Geldofen case

In the mid-1970s it became public that three Bundesbank employees had embezzled banknotes that should have been burned through various measures. In terms of origin, this was not counterfeit money; however, the notes were no longer intended for circulation and, analogous to the coin replicas in Karlsruhe, were to be regarded as forgeries. It was not possible to precisely determine the extent to which bills were returned to the cash cycle.

Introduction of machine-readable security features

In order to be able to recognize false banknotes even better, the Bundesbank installed devices in 1977 in Frankfurt and at the state central banks that scan special security features with the help of eight sensors and thus determine the authenticity of a banknote. Previously, this "hideously dull job" had been done manually by around 5000 people.

In the recession at the beginning of the 1980s, the rise in bankruptcy and unemployment figures also resulted in an increase in the amount of counterfeit money. In 1981, with 17,172 counterfeit coins valued at around DM 34,300, twice as many counterfeit coins were seized as in the previous year. In the 1980s, scanners were also used for the first time for counterfeiting, which then provided the templates for the printing machines. In 1987 around 12,000 counterfeit banknotes, mostly 50 and 100 mark notes, were seized.

The advent of color copiers

From the end of the 1980s, with the increasing spread of color copiers, they were used intensively for the production of counterfeit money. The CLC-500 from the manufacturer Canon , which cost around 80,000 marks at the time (adjusted for inflation in today's currency: around 70,000 euros), was particularly popular . The first copied notes appeared in 1988, but at that time the Bundesbank did not see any acute danger from counterfeit copies. In 1989 the police registered 243 counterfeit copies, in 1990 already 590, in 1991 there were 18,226 and in 1992 with 37,285 more than twice as many as in the previous year. In addition, so-called "combi-notes" have been in circulation since 1991, for the production of which both a copier and a printing machine are required and which have first-class colors and sharp contours. In 1993 Canon announced that it would incorporate an invisible serial number into the copies so that sources of counterfeit money could be better traced.

But not only the color copiers led to a glut of counterfeit money. After the collapse of socialism in Eastern Europe , there were many printing experts. A production facility was discovered in Poland which had produced 20 million marks in 100 and 200 banknotes; Thousands of 500 notes were made in Turkey . In Israel , around 90 million marks were produced in 1,000 D-mark notes. The D-Mark also enjoyed a good reputation as a safe currency in the formerly socialist countries. Since the population was not familiar with the security features of the D-Mark, there was also a large market for fake D-Mark banknotes there.

This glut of counterfeit money meant that many shops did not accept larger DM banknotes. Banks were asked to only insert checked bundles of banknotes into the ATMs so that they would not issue counterfeit notes. The retail sector responded by installing UV lamps at the checkouts. Test pens also came onto the market that detected the cotton of the banknote paper with the help of a chemical substance. Politicians also became active. In 1993, for example, members of the Bundestag Bernd Protzner ( CSU ) and Wolfgang von Geldern ( CDU ) demanded the introduction of 100 DM coins because they were supposed to be more forgery-proof.

From October 1993 to 1996 there was a large-scale counterfeit of 5 DM pieces. These consisted of a copper-nickel-zinc alloy and did not have a magnetizable core, so that they were not accepted by machines. However, the coins were visually very well made; Deviations had to be looked for with a magnifying glass. The coins, which were made in Italy , were brought into circulation by Eastern European petty criminals. Investigators at the Federal Criminal Police Office estimated around one million false coins; After his arrest, the perpetrator confessed to having minted around 300,000 counterfeit coins.

After the sharp rise in counterfeiting in the early 1990s due to color copiers, the number of counterfeit banknotes seized fell again in 1999 and 2000, only to increase significantly shortly before the end of the D-Mark era. Individual state criminal investigation offices recorded a doubling of counterfeit money cases in the first quarter of 2001 compared to the same period of the previous year.

Current situation

According to the Bundesbank, reproducing Deutsche Mark banknotes is no longer illegal after the introduction of the euro:

"Since the DM banknotes of all series are no longer legal tender, the restrictions of § 128 OWiG (as well as the criminal law provisions for the protection of money tokens according to §§ 146 ff. StGB ) and thus also derived specifications regarding size, resolution, Obligation to label or similar for their illustration meanwhile no longer; They are therefore basically freely reproducible from the point of view of criminal and administrative offenses. [...] "

literature

- Deutsche Bundesbank (Ed.): From cotton to banknotes. A new series of banknotes is created. Knapp, Frankfurt am Main 1995, ISBN 3-927951-82-X .

- Hans-Ludwig Grabowski : Small German paper money catalog. Battenberg Verlag, Regenstauf 2010, ISBN 978-3-86646-058-4 , pp. 102-109, 132-155.

- Günter Schön, Gerhard Schön: Small German coin catalog. 41st, revised and expanded edition. Battenberg Verlag, Regenstauf 2011, ISBN 978-3-86646-068-3 , pp. 172-306.

Web links

- DM banknotes and DM coins in circulation . In: Bundesbank.de

- The banknote replacement series from the time of the Deutsche Mark . In: Bundesbank.de (PDF)

- Catalog of DM coins . In: Münztreff.de

Individual evidence

- ↑ a b Exchange of DM into euros. Retrieved April 17, 2016 .

- ↑ a b Information from the Deutsche Bundesbank on outstanding DM cash