Lou Andreas-Salomé

Lou Andreas-Salomé (born Louise von Salomé ; occasional pseudonym Henri Lou ; at a young age also called Ljola von Salomé ) (born February 12, 1861 in St. Petersburg ; † February 5, 1937 in Göttingen ) was a widely traveled writer , narrator, Essayist and psychoanalyst from a Russian- German family. She gained fame through her literary work in the fields of religion, philosophy and cultural studies.

Life

Childhood, youth, studies

Her father Gustav Ludwig von Salomé (1807–1878) was descended from Huguenots in the south of France and came to St. Petersburg with his family in 1810 as a child. A military career led him to the general staff of the Russian army. In 1831 he was raised to the nobility by Tsar Nicholas I. The mother Louise b. Wilm (1823–1913) was of northern German- Danish origin. The two married in 1844, their daughter Louise von Salomé was born in St. Petersburg on February 12, 1861, the youngest of six children and the only girl. As her father's darling, she grew up in a wealthy, culturally diverse family in which three languages were spoken: German, French and Russian. In the happy and stimulating childhood, biographers see the basis for their consistently strong intellectual curiosity, for their inner security and independence, also for their sovereignty in dealing with more or less important men. Shortly before her death, she described her attitude towards life: "Whatever happens to me - I never lose the certainty that arms are open behind me to welcome me."

Louise caused some excitement and tension within her strictly Protestant family when she refused to receive confirmation from Hermann Dalton, the Orthodox Protestant pastor of the relevant Reformed congregation, and left the church at the age of 16. As an eighteen-year-old she was fascinated by the sermons of another Protestant pastor, the Dutch Hendrik Gillot, who was theologically considered an opponent of Dalton in St. Petersburg, accepted her as a student and discussed philosophical , literary and religious topics with her . The extent and intensity of these studies can be read from their notebooks. It included: Comparative Religious History ; Basic concepts of the phenomenology of religion . Dogmatism , messianic ideas in the Old Testament, and the doctrine of the Trinity ; Philosophy, logic , metaphysics and epistemology ; the French theater before Corneille , classical French literature, Descartes and Pascal ; Schiller , Kant and Kierkegaard , Rousseau , Voltaire , Leibniz , Fichte and Schopenhauer . Here the main features of that comprehensive education become visible, which, like her quick comprehension, repeatedly impressed later interlocutors.

Gillot was the pastor of the Dutch Embassy, 25 years her senior and had two children, a son and a daughter who was almost the same age as Lou. Now he announced that he wanted to separate from his wife and made his student a marriage proposal. Von Salomé refused. She was not interested in marriage or sexual relations; she was downright disappointed and shocked by this development, but remained friends with Gillot. This pattern was repeated many times in her life. Men made her extensive offers (mostly including physical intimacy). She accepted what she wanted and set the terms. She went on another trip to Holland with Gillot. There she was confirmed by him - otherwise she would not have received her own passport - and was baptized by him under the name "Lou".

After her father's death (1878), Lou von Salomé and her mother moved to Zurich in the autumn of 1880 and attended lectures as a (not officially enrolled) guest student at the University of Zurich from 1880–1881 , which was one of the few universities of that time to include women Study allowed. She took lectures in philosophy (logic, history of philosophy, ancient philosophy and psychology) and theology (dogmatics). A lung disease forced her to interrupt her studies. A warmer climate was recommended for her to heal. In February 1882, mother and daughter arrived in Rome .

Paul Rée and Friedrich Nietzsche

A letter of recommendation gave Lou von Salomé access to the circle of acquaintances of the writer, pacifist and women's rights activist Malwida von Meysenbug , who was once expelled from Berlin because of her open sympathies for the revolutionaries of 1848 and now a circle of artists and intellectuals in the tradition of Berliners in Rome Had established salons. The philosopher Paul Rée , a friend of Friedrich Nietzsche's , and also Nietzsche himself were in this circle . Rée immediately fell in love with Lou von Salomé, asked for her hand and was turned away; a close friendship developed between the two. When Nietzsche reached Rome in April 1882, enthusiastic letters from Rée prepared him for the meeting with von Salomé. He was also delighted by the "young Russian" and proposed marriage to her, through Rée of all people as a mediator. He was also rejected, but was very welcome as a friend, teacher and conversation partner.

Because in the meantime, without knowing him personally, she had drawn up the ideal of an intensive working group (what she called the “Trinity”) with Nietzsche, Rée and herself. One would live together on friendship in Vienna or Paris , study, write and discuss. This ideal of theirs, which was eagerly discussed with the three of them, could not be realized. It ultimately failed because of the jealousy of the two men - they did not want to be committed to the roles assigned to them (on the other hand, Nietzsche had repeatedly expressed the fear that any really close, lasting bond could prevent him from completing his life's work). The friendship between von Salomé and Paul Rée was relatively uncomplicated, but closer and more intimate than that of Nietzsche - they went on two terms, sent diary sheets to each other and discussed the current state of affairs in relation to Nietzsche, who knew nothing about any of this.

Its situation became increasingly unsatisfactory. At the beginning of May 1882 he had made a long excursion alone with von Salomé to the Sacro Monte di Orta in northern Italy - since then there has been reason to speculate about how close the two had come. In mid-May, a new marriage proposal followed in Lucerne , which was again rejected. This is where the well-known photo was taken, arranged in great detail by Nietzsche himself, on which Salomé pulls him and Rée in front of their cart.

A little later, Nietzsche's sister Elisabeth began to interfere in her brother's affairs. She told him about the supposedly "frivolous" and "scandalous" behavior of his girlfriend during the Festival in Bayreuth and also taught her mother about the morally dubious in their view affair. Nietzsche was outraged by his family's interference, but also suffered from the details that had been brought to him. Nietzsche and von Salomé spent the summer of 1882 philosophizing in Tautenburg . The relationship between the two was viewed critically by some contemporaries, such as the pastor Hermann Otto Stölten, who lives in Tautenburg .

Nietzsche's relationship with Lou von Salomé finally ended after a last encounter with her and Rée in Leipzig in autumn 1882, from where von Salomé left without saying goodbye to him. After that, Nietzsche's attitude and behavior towards both changed. In a draft letter from December 1882 he expressed despair and self-pity: "Every morning I despair as I endure the day ... Tonight I will take so much opium that I lose my mind: Where is another man? might worship! But I know you all through and through. ”In uncontrolled jealousy, he made serious accusations to Rée and von Salomé and went wildly to insult and insult even third parties. After that you never saw each other again.

Later Nietzsche regretted his behavior in a letter to his sister - both with regard to the lost friendship and for fundamental considerations: “No, I am not made for enmity and hatred: and since this thing has progressed so far that one Reconciliation with those two is no longer possible, I no longer know how to live; I keep thinking about it. It is incompatible with my whole philosophy and way of thinking ... ”In January 1883 he wrote the first part of Zarathustra in Rapallo , overcoming his acute crisis and, as he noted,“ rolled a heavy stone off his soul ”. From the chapters that relate to the essence of women, one can read traces of his experiences with von Salomé, but at the same time the conclusion and coping with this episode of his life. He remained alone until the end of his life; after his complete mental breakdown in January 1889, he was cared for by his mother and sister until he died on August 25, 1900. In her book “Nietzsche in his Works” from 1894, von Salomé tried, on the basis of her precise knowledge of the text and her personal experience with her difficult friend, to “explain the thinker through man”. Anna Freud later said that Lou Andreas-Salomé had anticipated psychoanalysis with this book about Nietzsche .

Lou von Salomé and Paul Rée were friends in Berlin for three years and separated in 1885. Rée died in 1901 while hiking in the mountains; It remained unclear whether this was due to an accident or suicide .

Marriage

In August 1886 Lou von Salomé met the orientalist Friedrich Carl Andreas in Berlin . He was fifteen years older than her, dark-haired, spirited, and soon determined to marry her. He underscored his determined intention by attempting suicide in front of her eyes. After lengthy internal struggles, she agreed to the marriage in 1887, but set conditions. The main thing: you will never find yourself ready to consummate the marriage sexually. It is not known why Andreas accepted this. If he hoped - as is usually assumed - that she would not mean it seriously in the long term, he was disappointed. In the first years of the marriage there were repeated scenes of jealousy because of her relationships with other men. Nevertheless, Andreas refused several times to get a divorce. In Berlin the couple lived one after the other in different apartments, at times Andreas had professional difficulties and only very little income, so that the equally limited income his wife earned as a writer was urgently needed.

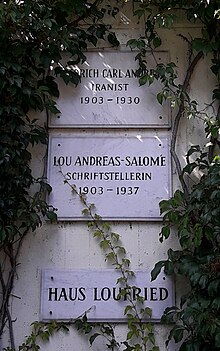

Lou Andreas-Salomé's life consisted of a conventional , middle-class half with a husband, housewife fulfilling duties and intellectual work - and another area in which she accepted neither duties nor closer ties and was on the road with occasional, unofficial lovers. At the same time, she initially accused her husband of his relationship with her housekeeper Marie. But she, too, took care of the child from this connection after the mother died early, and later appointed him as the chief heir. In the long run, the difficult, contradicting marriage proved unexpectedly tenable. Since Friedrich Carl Andreas was appointed to the chair for West Asian languages at the University of Göttingen in the spring of 1903 , the couple lived there in their own house (called "Loufried" by her, like a previous place of residence) - he and the housekeeper on the ground floor, them on the floor above. When she was in Göttingen, she looked after the garden at the house, she grew vegetables and kept chickens, but essentially continued to lead an independent, travel-friendly life. In her diary notes, this phase of life, especially her relationship with her husband, appears to be much more relaxed than the time before.

The Berlin Circle

When Lou von Salomé lived with Paul Rée in Berlin, i.e. from 1882 to 1885, their mutual circle of acquaintances consisted mainly of scientists - their friends and colleagues Rées. Von Salomé was the only woman in this circle, she enjoyed the admiration of the men and the participation in the philosophical and scientific discussions. In 1885, under the pseudonym Henri Lou, her first book appeared, the novel In the fight for God , topic: "What happens when a person loses his faith?" She had to deal with the problem in her own youth. The reviews were good, the pseudonym was easy to see through, the success made her known in wider circles of Berlin society.

After her marriage to Friedrich Carl Andreas, she made new contacts, in particular to the so-called “ Friedrichshagener Dichterkreis ” and the “Freundeskreis der Freie Volksbühne ” - both of them largely identical in terms of personnel. Around 1890, a loose association of writers and nature lovers had come together in the idyllic Berlin suburb of Friedrichshagen , with the aim of leading a casual life and renewing poetry and theater in the spirit of naturalism . Bruno Wille , one of the initiators, was one of the founders of the “Freie Volksbühne” in 1890, which was supposed to give workers access to dramatic art. Members or sympathizers of these initiatives included Wilhelm Bölsche , Otto Brahm , Richard Dehmel , Max Halbe , Knut Hamsun , Maximilian Harden , Gerhart Hauptmann , Hugo Höppener (called Fidus ), Erich Mühsam and Frank Wedekind , temporarily also August Strindberg , Hulda and Arne Garborg . Lou Andreas-Salomé was soon friends or well known to a number of them, Hauptmann and Harden in particular, being impressed by her. She also published articles and reviews in the magazine “ Freie Bühne ”, which accompanied the Volksbühne project. In this context, her interest in the dramas by Henrik Ibsen , with which the Volksbühne had opened, grew . She examined his portrayal of marital problems with the question that was important to her: How must a marriage be designed to allow room for self-realization, especially for women? Her 1892 book Henrik Ibsen's Frauengestalten on this subject received undivided applause and cemented her reputation as a notable author.

Rainer Maria Rilke

Rainer Maria Rilke had been in Munich since 1896 and was reasonably successful with poems and stories that were still quite undemanding in literary terms. When Lou Andreas-Salomé visited her friend Frieda von Bülow in Munich from Berlin in the spring of 1897 , Rilke was introduced to her by Jakob Wassermann . What she did not know at the time: he had already sent her a number of anonymous letters with poems attached. Now he assured her how extremely impressed he was by her religious-philosophical essay Jesus the Jew , in which she "so masterfully and clearly expressed with the gigantic force of a holy conviction" what he himself wanted to express in a cycle of poems; he ran around "with a few roses in the city and the beginning of the English Garden ... to give you the roses", read to her from his work, dedicated a poem to her - a little later he was successful with his intensive advertising.

Several summer months followed in the market town of Wolfratshausen in the Isar valley near Munich. They lived in three chambers in a farmhouse and called the accommodation "Loufried". When Lou Andreas-Salomé went back to Berlin, Rilke followed her there. He was 21 years old. Andreas-Salomé, whom he adored profusely as a motherly lover, was 36. She was also deeply in love, but at the same time, in keeping with her nature, maintained control over herself and the situation. She made him work on his linguistic expression, which she found exaggeratedly pathetic. According to your suggestion, he changed his real first name René to Rainer . She introduced him to Nietzsche's thinking and directed his interest to her native Russia; he learned Russian and began to read Turgenev and Tolstoy in the original. All of this happened mainly in the narrow Berlin apartment of the Andreas-Salomé couple. Rilke had rented a room nearby, but mostly stayed with Lou Andreas-Salomé, who had her living room and office in the kitchen while her husband worked in the living room. Andreas-Salomé soon discovered that the young, psychologically unstable poet's inner dependence on her was steadily increasing - an undesirable development. So in the spring of 1898 she urged him to go on a trip to Italy on which she did not accompany him.

In 1899 and 1900 they made two trips to Russia together, the first, shorter (April 25 to June 18, 1899) accompanied by Andreas. The second trip lasted from May 7th to August 24th 1900 and is considered a turning point in the relationship between Andreas-Salomé and Rilke (a third trip was planned for 1901, but did not materialize). The Pentecost both spent in Kiev . The strong impressions and feelings of this time are said to have found their expression in his famous book of hours (written from 1899 to 1903). But they also gave him cause for crying fits, for "anxiety states and physical attacks", as Andreas-Salomé remembered in her life review. She was shocked and worried, suspecting that the background was serious mental illness. During a trip to her family's vacation spot in Finland in August 1900 , she decided to part ways with Rilke. In fact, she only ended the love affair with a farewell letter dated February 26, 1901. In the meantime, she confirmed her resolution in diary notes: “What I want from the coming year, what I need, is almost only silence - more solitude, like it until four years ago. That will, must come again "-" Denied me in front of R. with lies "-" In order for R. to go away, I would be capable of brutality (he has to go!) "

The passionate relationship turned into a close friendship that lasted until Rilke's death in 1926. In 1937, Sigmund Freud recalled in his obituary for Lou Andreas-Salomé that “she was both muse and caring mother to the great poet Rainer Maria Rilke, who was quite helpless in life ”.

Sigmund Freud and Psychoanalysis

During a stay in Sweden, Lou Andreas-Salomé began an intense relationship with a man 15 years his junior, the neurologist and Freudian Poul Bjerre. When he went to the congress of the International Psychoanalytic Association in Weimar in 1911 , she accompanied him and met Sigmund Freud there for the first time . He became the key figure in the last 25 years of her life. She suspected and hoped that the new school of thought in psychoanalysis - with Freud as the father figure - could give her access to an understanding of her own mental state. She stayed in Vienna from October 1912 to April 1913, and many more visits followed later. In the winter semester of 1912/1913 she heard Freud's lecture in the psychiatric clinic on "Individual chapters from the theory of psychoanalysis" and took part in his "Wednesday sessions" and "Saturday colleges". With Freud's express consent, she also took part in the discussion evenings by Alfred Adler , who in 1911 had distanced himself from Freud's orthodox psychoanalytic school and founded his own depth psychology school with his association for individual psychology .

Sigmund Freud thought a lot of his student. In a close, purely platonic relationship, she became a valued discussion partner for him through her thirst for knowledge, her curiosity about human behavior and the intensive search for their understanding. He even accepted her idiosyncratic interpretation of psychoanalytic concepts, to which she gave a predominantly poetic and literary form, without contradiction. He thought she was the "poet of psychoanalysis" while he wrote prose himself. In the "Schule bei Freud" (the title of her posthumously published diary from 1912/1913) Lou Andreas-Salomé learned to understand and control her own life better, something she attached particular importance to in view of her advanced age.

Freud advised her to become a psychoanalyst . She wrote essays for the psychoanalytic journal "Imago" and was a guest speaker at the Psychoanalytic Congress in Berlin as early as 1913. In 1915 she opened the city's first psychoanalytical practice in her Göttingen house. Her friendship with Anna , one of Freud's three daughters, began in 1921, and a year later she was accepted into the Vienna Psychoanalytic Association together with Anna Freud . In 1923, at Sigmund Freud's request, she went to Königsberg as a training analyst for half a year , five doctors completed a training analysis with her (which she had never undergone herself). On the 75th birthday of her friend and teacher on May 6, 1931, she wrote the open letter My thanks to Freud . The addressee replied: “It certainly doesn't happen very often that I have a psa. I admired [psychoanalytic] work instead of criticizing it. I have to do that this time. It's the best thing I've read of you, involuntary evidence of your superiority over all of us. "

End of life

Lou Andreas-Salomé had become increasingly weak, had heart and diabetes and had to be treated several times in hospital. When she was hospitalized for a foot operation in 1930, her husband visited her every day for six weeks, a difficult situation for the old man, who was also sick. After forty years of marriage with mutual grievances and long speechlessness, the two had grown closer. Sigmund Freud welcomed this from afar: “Only the real thing proves itself so permanently”. But in the same year Friedrich Carl Andreas died of cancer. Lou Andreas-Salomé had to undergo serious cancer surgery in 1935. She had previously given up her last patient. She died in her sleep on the evening of February 5, 1937.

According to her wishes, Lou Andreas-Salomé was cremated after her death. However, since the Göttingen authorities did not allow her urn to be buried in the garden of her house, she was finally buried in her husband's grave in the city cemetery there (Grabfeld 68).

A few days after her death, the Göttingen police, on the orders of the Gestapo, confiscated her library and took it to the cellar of the town hall. The reason given for the seizure was that Lou Andreas-Salomé was a psychoanalyst, that she was engaged in “Jewish science”, that she was an employee of Sigmund Freud and that her library contains numerous works by Jewish authors.

A memorial stone on the newly built property of her former home, a “Lou-Andreas-Salomé-Weg” and the “Lou Andreas-Salomé Institute for Psychoanalysis and Psychotherapy” remind Göttingen of the former resident.

Reception of life and work

Lou Andreas-Salomé's often praised personal charisma, her education and intellectual agility, friendship with well-known contemporaries and her unconventional lifestyle secured her a place in German cultural history . Her life was and is the subject of biographies , fiction , music theater (the opera Lou Salomé by Giuseppe Sinopoli (libretto: Karl Dietrich Graewe ), for example, which premiered in Munich in 1981) and other texts in which her contacts with celebrities in literature and the history of science are discussed.

Compared to this, her own writing has received little attention since then - it disappeared behind the extraordinary story of her life. As a renowned author, she played a lively role in the development of the positions of modernism around 1900. In novels, stories, essays, theater reviews, writings on Ibsen, Nietzsche, Rilke and Freud, an autobiography, numerous texts on philosophy and psychoanalysis, and extensive correspondence, she participated in the discussions on fundamental questions of the time - with contributions to the life reform movement , to Monism , for the emancipation of women, reform pedagogy , the beginnings of sociology and psychoanalysis. In her novels and stories she dealt with the problems of modern women who try to go their own way in an environment steeped in tradition; Despite this choice of topics and her own lifestyle, which was atypical for women of her time, she kept a distance from the social and political goals and activities of the women's movement of her time. It was not until the second half of the 20th century that most of her work was viewed and published.

Produced in 2015 and in cinemas from June 30, 2016, the film Lou Andreas-Salomé by director Cordula Kablitz-Post describes her life; the title role was played by Katharina Lorenz .

Personal judgments

“She was an unusual person, you could tell immediately. She had the gift of putting herself right into someone else's mind ... In my long life, I have never met anyone again who understood me as quickly, as well and as completely as Lou. She had an unusually strong will and joy in triumphing over men. It could ignite, but only for a moment and with a strangely cold passion. It hurt me, but it also gave me a lot. "

"She is an energetic, incredibly clever being ... I give lectures about my book at Fräulein von Meysenbug, which is somewhat beneficial, especially since the Russian woman listens, who listens to everything through and through, so that she always knows in advance in an almost annoying way what is coming and what it should be. Rome wouldn't be for you. But you definitely have to get to know the Russian. "

“Lou is astute as an eagle and brave as a lion ... She comes to me after Bayreuth, and in the autumn we will move to Vienna together. We will live in one house and work together; it is prepared in the most amazing way for my way of thinking and thinking. Dear friend, you certainly do us both the honor of keeping the concept of a love affair away from our relationship. We are friends and I will hold sacred this girl and this trust in me. - By the way, she has an incredibly safe and louder character.

"That skinny, dirty, foul-smelling monkey with her fake breasts - a fate!"

“If you were the most maternal of women to me,

you were a friend like men are,

a woman, then you were to be looked at,

and more often you were a child.

You were the tenderest thing I met, you were the toughest to make me wrestle

.

You were the high that blessed me -

and became the abyss that swallowed me up. "

“The last 25 years of this extraordinary woman's life belonged to psychoanalysis, to which she contributed valuable scientific work and which she also practiced. I am not saying much when I confess that it was an honor for us to see her join the ranks of our co-workers and supporters ... My daughter [Anna], who was familiar with her, has heard her regret that she had gone through psychoanalysis hadn't met in her youth. Of course there weren't any back then ... "

"It is neither weakness nor inferiority of the erotic if it is, according to its nature, on tense feet with loyalty, rather it signifies in him the mark of his ascent to further contexts."

"I am faithful to memories forever: I will never be people."

"We want to see whether the vast majority of so-called 'insurmountable barriers' that the world draws turn out to be harmless chalk lines!"

Works

- In the fight for God. 1885 (2007, ISBN 978-3-423-13529-0 ).

- Henrik Ibsen's female figures. 1892 (re-edited with comments and afterword by Cornelia Pechota, Taching am See. MedienEdition Welsch 2012, ISBN 978-3-937211-32-9 ).

- Friedrich Nietzsche in his works. 1894 (reissued with comments and afterword by Daniel Unger, Taching am See, MedienEdition Welsch 2019, ISBN 978-3-937211-53-4 ).

- Ruth. 1895 (reissued with comments and afterword by Michaela Wiesner-Bangard, Taching am See, MedienEdition Welsch 2008, ISBN 978-3-937211-02-2 ; 2nd edition 2017, ISBN 978-3-937211-24-4 ).

- Jesus the Jew. 1895 (in: Lou Andreas-Salomé: Essays and Essays. Volume 1: From the Beast to God. Taching am See, MedienEdition Welsch 2010, ISBN 978-3-937211-08-4 ).

- From a strange soul. 1896 (2007, ISBN 978-3-423-13596-2 ).

- Fenitschka. A debauchery. 1898 ( digitized and full text in the German Text Archive , ISBN 3-548-30315-3 ); (newly published with comments and afterword by Iris Schäfer, Taching am See, MedienEdition Welsch 2017, ISBN 978-3-937211-71-8 ).

- Human children. 1899 (re-edited with comments and afterword by Iris Schäfer, Taching am, MedienEdition Welsch 2017, ISBN 978-3-937211-56-5 ).

- Ma (novel) . A portrait. 1901.

- The secret way. 1900/01 (newly published with comments and afterword by Edith Hanke, Taching am See, MedienEdition Welsch 2017, ISBN 978-3-937211-59-6 ).

- In the intermediate country. 1902 (re-edited with comments and afterword by Britta Benert, Taching am See, MedienEdition Welsch 2012, ISBN 978-3-937211-29-9 ).

- The erotic. 1910, ISBN 3-88221-302-7 , ISBN 3-926023-17-1 (reissued with comments and epilogue by Katrin Schütz, Taching am See, MedienEdition Welsch 2015, ISBN 978-3-937211-42-8 ).

- Elisabeth Siewert . In: Ernst Heilborn (Ed.): The literary echo . 14th year 1911/12, September 15, 1912, Berlin, pp. 1690–1695 (→ abstract ); (in: Lou Andreas-Salomé: Essays and Essays. Volume 3.1: Living Poetry. Taching am See, MedienEdition Welsch 2011, ISBN 978-3-937211-14-5 ).

- From the early church service. 1913 (in: Lou Andreas-Salomé: Essays and Essays. Volume 1: From the Beast to God. Taching am See, MedienEdition Welsch 2010, ISBN 978-3-937211-08-4 ).

- To the woman type. 1914 (in: Lou Andreas-Salomé: Essays and Essays. Volume 4: My thanks to Freud. Taching am See, MedienEdition Welsch 2012, ISBN 978-3-937211-17-6 ).

- "Anal" and "Sexual". 1916; first published 1915–1916 In: Imago. IV Issue 5 (in: Lou Andreas-Salomé: Essays and Essays. Volume 4: My thanks to Freud. Taching am See, MedienEdition Welsch 2012, ISBN 978-3-937211-17-6 ).

- Psychosexuality. 1917 (in: Lou Andreas-Salomé: Essays and Essays. Volume 4: My thanks to Freud. Taching am See, MedienEdition Welsch 2012, ISBN 978-3-937211-17-6 ).

- Three letters to a boy. 1917 (re-edited with comments and an afterword by Inge Weber and Brigitte Rempp, Taching am See, MedienEdition Welsch 2008, ISBN 978-3-937211-05-3 ; 2nd edition 2015, ISBN 978-3-937211-45-9 ).

- Narcissism as a double direction. 1921 (in: Lou Andreas-Salomé: Works and Letters. Volume 4: My thanks to Freud. Taching am See, MedienEdition Welsch 2012, ISBN 978-3-937211-17-6 ).

- The House. A family story from the end of the last century. 1921.

- The hour without God. and other children's stories. 1922 (reissued with comments and afterword by Britta Benert, Taching am See, MedienEdition Welsch 2016, ISBN 978-3-937211-47-3 ).

- The devil and his grandmother. Dream game. 1922 ( digitized edition of the University and State Library Düsseldorf ).

- Rodinka. A Russian memory. 1923 (2015, ISBN 978-3-945796-38-2 )

- Rainer Maria Rilke (Book of Remembrance). 1928 (1988, ISBN 3-458-32744-4 ).

- My thanks to Freud. Open letter , 1931 (in: Lou Andreas-Salomé: Works and Briefe. Volume 4: My thanks to Freud. Taching am See, MedienEdition Welsch 2012, ISBN 978-3-937211-17-6 ).

Publications from the estate

- The God. 1910 (edited from the estate, annotated and with an afterword by Hans-Rüdiger Schwab, Taching am See, MedienEdition Welsch 2016, ISBN 978-3-937211-38-1 ).

- Life review - outline of some memories. 1951/1994, ISBN 3-518-38840-1 .

- Rainer Maria Rilke - Lou Andreas Salomé: Correspondence. 1952.

- At Freud's school - diary of a year - 1912/1913. (Newly edited from the estate, annotated and with an afterword by Manfred Klemann, Taching am See, MedienEdition Welsch 2017, ISBN 978-3-937211-50-3 ).

- Sigmund Freud - Lou Andreas-Salomé: Correspondence. 1966.

- Friedrich Nietzsche, Paul Rée, Lou von Salomé. The documents of their meeting. 1970.

- Amor (1897) - Jutta (1933) - The magic hat. Three seals. 1981.

- “As if I were coming home to my father and sister” Lou Andreas-Salomé - Anna Freud: Correspondence. Wallstein Verlag, Göttingen 2001, ISBN 3-89244-213-4 .

- Le diable et sa grand-mère. 1922; Translation and comments by Pascale Hummel , 2005

- L'heure sans Dieu et autres histoires pour enfants. 1922; Translation and comments by Pascale Hummel (2006)

- Correspondence with Arthur Schnitzler : Arthur Schnitzler - Correspondence with authors. Edited by Martin Anton Müller, Gerd-Hermann Susen, online

Literature and film

Books

- Dorian Astor: Lou Andreas-Salomé (= folio biographies . 48). Gallimard, Paris 2008, ISBN 978-2-07-033918-1 .

- Britta Benert / Romana Weiershausen (ed.): Lou Andreas-Salomé: Zwischenwege in der Moderne / Sur les chemins de traverse de la modernité . Welsch, Taching am See 2019. ISBN 978-3-937211-82-4 .

- Kerstin Decker : Lou Andreas-Salomé. The bittersweet spark of me. 3. Edition. Propylaeen-Verlag, Berlin 2011, ISBN 978-3-549-07384-1 .

- Christina Deimel: Lou Andreas-Salomé - The poet of psychoanalysis. In: Sibylle Volkmann-Raue, Helmut E. Lück (Ed.): Important psychologists. Biographies and Writings (= Beltz Taschenbuch 136). Beltz, Weinheim u. a. 2002, ISBN 3-407-22136-3 , pp. 13-29.

- Elisabeth Förster-Nietzsche : Friedrich Nietzsche et les femmes de son temps (1935). Traduction, annotation et postface by Pascale Hummel . Michel de Maule, Paris 2007, ISBN 978-2-87623-202-0 .

- Carola L. Gottzmann / Petra Hörner: Lexicon of the German-language literature of the Baltic States and St. Petersburg . 3 volumes; Verlag Walter de Gruyter, Berlin 2007. ISBN 978-3-11-019338-1 . Volume 1, pp. 141-144.

- Elisabeth Heimpel : Andreas-Salomé, Lou. In: New German Biography (NDB). Volume 1, Duncker & Humblot, Berlin 1953, ISBN 3-428-00182-6 , p. 284 f. ( Digitized version ).

- HFPeters: Lou. Das Leben der Lou Andreas-Salomé , Kindler Verlag, Munich 1964 (The original edition was published under the title My Sister, My Spouse by WW Norton & Company, Inc., New York)

- Irmgard Hülsemann: Lou. The life of Lou Andreas-Salomé. Claassen, Munich 1998, ISBN 3-546-00152-4 .

- Cordula Koepcke: Lou Andreas-Salomé. Life, personality, work. A biography (= Insel-Taschenbuch 905). Insel-Verlag, Frankfurt am Main 1986, ISBN 3-458-32605-7 .

- Stéphane Michaud: Lou Andreas-Salomé. L'alliée de la vie. Seuil, Paris 2000, ISBN 2-02-023087-9 .

- Cornelia Pechota Vuilleumier: “O father, let's move!” Literary father-daughters around 1900. Gabriele Reuter , Hedwig Dohm , Lou Andreas-Salomé (= Haskala . 30). Olms, Hildesheim u. a. 2005, ISBN 3-487-12873-X (also: Lausanne, Univ., Diss., 2003).

- Cornelia Pechota Vuilleumier: Home and eeriness with Rainer Maria Rilke and Lou Andreas-Salomé. Literary interactions (= German texts and studies . 85). Olms, Hildesheim u. a. 2010, ISBN 978-3-487-14252-4 .

- Ursula Renner: Not just knowledge, but a piece of life. In: Barbara Hahn (Hrsg.): Women in the cultural studies. From Lou Andreas-Salomé to Hannah Arendt (= Beck's series . 1043). Beck, Munich 1994, ISBN 3-406-37433-6 , pp. 26-43.

- Heide Rohse: “Look, I'm like that.” The writer Lou Andreas-Salomé between literature and psychoanalysis. In: Hermann Staats, Reinhard Kreische, Günter Reich (eds.): Inner world and the formation of relationships. Göttingen contributions to the applications of psychoanalysis. Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, Göttingen 2004, ISBN 3-525-49084-4 , pp. 142-168.

- Werner Ross : Lou Andreas-Salomé. Companion of Nietzsche, Rilke, Freud. Siedler, Berlin 1997, ISBN 3-88680-432-1 ( CORSO at Siedler ).

- Linde Salber: Lou Andreas-Salomé. Biography (= Rowohlt's Monographs 463). Represented with testimonials and photo documents. Rowohlt, Reinbek near Hamburg 1990, ISBN 3-499-50463-4 .

- Hans Rüdiger Schwab: Lou Andreas-Salomé: I-born in the unworldly. In: Swiss monthly books . Journal of Politics Economy Culture. Edition January / February 2007, p. 57 ff.

- Ursula Welsch, Dorothee Pfeiffer: Lou Andreas-Salomé. A picture biography. Reclam, Leipzig / Stuttgart 2006, ISBN 3-379-00877-X .

- Gunna Wendt: Lou Andreas-Salomé and Rilke - an amour fou (= Insel-Taschenbuch 3652). Insel-Verlag, Berlin 2010, ISBN 978-3-458-35352-2 .

- Christiane Wieder: The psychoanalyst Lou Andreas-Salomé. Her work in the field of tension between Sigmund Freud and Rainer Maria Rilke. Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, Göttingen 2011, ISBN 978-3-525-40171-2 .

- Michaela Wiesner-Bangard, Ursula Welsch: Lou Andreas-Salomé. "How I love you, puzzle life ..." A biography (= Reclam library 20039). Reclam, Leipzig 2002, ISBN 3-379-20039-5 .

- Wilhelm Szewczyk: Marnotrawstwo serca czyli Lou Andreas Salome (a waste of heart that is Lou Andreas Salome), Wydawnictwo Slask, 1980, ISBN 83-216-0037-9 .

Essays

- Ludger Lüdkehaus: "What God promises, life must keep." A portrait for the 150th birthday. In: The time. February 3, 2011, p. 20.

- Cornelia Pechota: Lou Andreas-Salomé between Königsberg and Kaliningrad. A biographical experience in a historical context. In: cultural sociology. 1/14, pp. 56-66.

- Hans-Rüdiger Schwab: “To my memory”. Nietzsche and Lou Andreas-Salomes “Prayer to Life”. In: Christian Benne / Claus Zittel (eds.): Nietzsche and the lyric. A compendium. Stuttgart 2017, pp. 479–491

- Gerd-Hermann Susen (Ed.): Wilhelm Bölsche . Correspondence with authors of the Freie Bühne. Berlin: Weidler Buchverlag 2010 (letters and comments), pp. 367–497

- Gerd-Hermann Susen: Poetry and Truth. Lou Andreas-Salomé's literary beginnings as reflected in the traditional correspondence (with a print of her letters to Hulda and Arne Garborg ). In: text & kontext 34/2012, pp. 63–96

motion pictures

- 2016: Lou Andreas-Salomé by Cordula Kablitz-Post.

Web links

- Literature by and about Lou Andreas-Salomé in the catalog of the German National Library

- Works by and about Lou Andreas-Salomé in the German Digital Library

- Annotated link collection of the university library of the FU Berlin ( Memento from May 13, 2013 in the web archive archive.today ) (Ulrich Goerdten)

- Works by Lou Andreas-Salomé in the Gutenberg-DE project

- Lou Andreas-Salomé in the Internet Archive

- Freud's obituary (1937) in the International Journal of Psychoanalysis

- NEWW Women Writers

- Lou Andreas-Salomé (compiled by Kazem Sadegh-Zadeh)

- Lou Andreas-Salomé (compiled by Ursula Welsch)

Individual evidence

- ^ Lou Andreas-Salomé - Lou Andreas-Salomé Institute for Psychoanalysis and Psychotherapy, Göttingen. Retrieved April 27, 2020 .

- ↑ Eugène von Salomé (* 1858); Alexander von Salomé (* 1849); Robert of Salomé (* 1851)

- ↑ Ernst Pfeiffer (ed.), Lou Andreas-Salomé: Life review. Issued from the estate. Insel, Frankfurt 1968. Again at: Europ. Hochschulverlag 2011, ISBN 978-3-86267-076-5 . From this, The Freud Experience also in Marlis Gerhardt (Ed.): Essays of famous women. From Else Lasker-Schüler to Christa Wolf . Insel, Frankfurt 1987, again 1997, ISBN 3-458-33641-9 . With short biographies.

- ↑ Andreas Urs Sommer (ed.): Friedrich Nietzsche and Lou von Salomé in Tautenburg. Excerpts from the unpublished autobiography of Pastor Hermann Otto Stölten. In: Nietzsche Studies. International yearbook for Nietzsche research. Volume 38 (2009), pp. 389-392.

- ↑ a b Text by Josef Bordat from recenseo - Texts on Art and Philosophy , 2007 ( Memento from December 27, 2016 on WebCite )

- ↑ Extensive information on encounters with contemporaries and their short biographies

- ↑ a b c d e Extensive website about Lou Andreas-Salomé

- ^ Review of a book on Lou Andreas-Salomé and other women writers

- ↑ Lou at the end of her life in lou-andreas-salome.de

- ^ Heinz F. Peters: Lou Andreas-Salomé: The life of an extraordinary woman. Kindler, Munich 1964, p. 7 (preface, without reference to source).

- ↑ Katja Iken: The woman with the whip ( Spiegel online , June 29, 2016)

- ↑ a b Bjerre was a Swedish psychotherapist. Quoted from Wolf Scheller: Die Mitdenkerin. A portrait of the writer Lou Andreas-Salomé ; 2004 (pdf, 69 kB)

- ↑ Quoted from Helmut Walther: Scherz, List und Rache. The Lou episode: Friedrich Nietzsche, Paul Rée and Lou Salomé. Lecture to the Society for Critical Philosophy Nuremberg on May 30, 2001. html ( Memento from May 29, 2013 in the Internet Archive ); pdf (474 kB) ( Memento from May 29, 2013 in the Internet Archive )

- ^ Friedrich Nietzsche: Critical Complete Edition. Correspondence. Berlin / New York 1975, Volume 3, p. 402.

- ^ Letter to Gillot. March 1882

- ↑ Süddeutsche Zeitung of June 24, 2016: Freifrau

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Andreas-Salomé, Lou |

| ALTERNATIVE NAMES | Louise von Salomé, Henri Lou (pseudonym) |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | German writer, narrator and essayist |

| DATE OF BIRTH | February 12, 1861 |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | Petersburg |

| DATE OF DEATH | February 5, 1937 |

| Place of death | Goettingen |