Divine Comedy

The Divine Comedy , originally Comedia or Commedia in Italian , later also called Divina Commedia , is the main work of the Italian poet Dante Alighieri (1265–1321). It originated during the years of his exile and was probably started around 1307 and only completed a short time before his death (1321). The Divina Commedia, which is divided into Hell , Purgatory and Paradise , is considered the most important poetry in Italian literature and has the Italian languageestablished as a written language. It is also considered to be one of the greatest works in world literature .

Politically, the emergence and aftermath of the work was related to the long-running conflict between Ghibellines and Guelphs (followers of the emperors and popes), which ruled medieval Italy, which is not discussed here, especially since Dante's poetry turned out to be timeless in contrast to this conflict Has. Dante himself was one of the emperor-friendly White Guelphs in his hometown of Florence, described as "almost Ghibelline" .

introduction

The three realms of the hereafter

Following on from the genre of medieval visions of the hereafter , the commedia depicts in the first person a journey through the three realms of the world beyond. It leads first through hell ( inferno ), which as a huge underground funnel reaches to the center of the spherical earth, which is only inhabited in the northern hemisphere and is divided into nine circles of hell, the penal districts of those who are condemned to eternal damnation for their sins are. Next it goes through the purification area ( purgatorio , in German ' purgatory '), presented as a mountain rising out of the ocean on the southern hemisphere, on which the souls of those who could still be forgiven for their sins, on a spiral path through seven Penitential districts to make a pilgrimage to earthly paradise , the Garden of Eden on the summit of the mountain. From the earthly the traveler finally ascends to the heavenly paradise ( Paradiso ) with its nine heavenly spheres, above which in Empyrean the souls of the saved enjoy the joys of eternal bliss in the face of God.

The hereafter leaders

The traveler is led by various guides from the hereafter , through Hell and Purgatorio, initially by the Roman poet Virgil , to whom the poet Statius joins from the fifth penitential district of the Cleansing Mountain, the penitentiary area of the avaricious , who converts to Christianity according to a legend recorded by Dante should have.

As a pagan of pre-Christian times, Virgil himself is excluded from redemption in the absence of the sacrament of baptism . But because of his virtuous life and his role as a poet of Weltkaisertums and foreboding prophet of the coming of Christ (in his fourth Eclogue ) the punishments of hell remain him spared, and he may, until the time the final judgment in which the actual hell upstream limbus spend, together with other righteous men of paganism and Islam . Only in his capacity as a guide in the divine commission is he allowed to leave Limbo temporarily and accompany the visitor to the hereafter through hell and the area of purification. As a representative of natural reason, which, at least during Virgil's lifetime, was not yet enlightened by biblical revelation, he explains to Dante the principles of dividing the penal and penitential districts into hell and purgatorio . But not only as a philosophical-ethical teacher who instructs his protégé and on some occasions also admonishes, but also as a literary role model, namely as the poet of Aeneas' voyage under the world in the sixth book of the Aeneid , he advances Dante.

His role ends at the threshold of earthly paradise, where Dante von Matelda, a woman who cannot be interpreted with certainty from a historical point of view, is received and passed on to Beatrice , his deceased childhood sweetheart, who was already at the center of his Vita Nova . After a solemn re-encounter with Beatrice, who floats down in a cloud of flowers, followed by a penitential sermon by Beatrice about Dante's past transgressions, Dante is subjected to a cleansing bath in the paradise river Lethe on behalf of Beatrice by Matelda , which erases the memory of his evil deeds, and again later - following a visionary show of allegorical and symbolic events around the chariot of the church at the foot of the tree of knowledge - a second ritual bath, this time in the river Eunoë , the water of which renews the memory of good deeds. Matelda, whose name is only incidentally pronounced by Beatrice, remains a figure tied to earthly paradise without a very personal physiognomy or physiognomy that can be illuminated through a known previous relationship with Dante, but acts as guardian of paradise and executing servant Beatrice in a prominent position and offers her name, her role and the literary characteristics of her presentation make puzzling traits that one can relate to the biblical Eve, to mythological figures such as Proserpina and to persons of recent history, especially the Margravine Mathilde of Tuscany .

Immersed in the sight of his beloved Beatrice, Dante is transported with her to a flight through the heavenly spheres, where she explains the order of the universe to him as a guide and teacher. He solves astronomical riddles and theological problems and leads him to the light souls of the saints. As in the relationship with Virgil, Dante's relationship with Beatrice is characterized by tenderness and admiration, but also by the delight that overwhelms him again and again and the joy of the beauty of the divine order, which is reflected in the sight of Beatrice and especially in her eyes . Beatrice bears traits of the Donna filosofia (lady philosophy) from Dante's Convivio , is, going beyond this and beyond the ethical-philosophical role of Virgil, at the same time a representative of theology and, based on biblical comparisons, can even be interpreted as a figure of Ecclesia, the Church of Christ as a figure of Christ himself or at least a figure with attributes typical of Christ, such as the cloud in which, like Christ at the Second Coming to the Last Judgment, she floats over Dante in the earthly paradise for her penitential judgment.

Beatrice's role ends in the empyrean vaulting over the spheres of heaven , where she takes her place under the saints arranged like the leaves of a rose and takes her place in third place of these saints, together with the biblical Rachel and below the first mother Eve, at the feet of the mother of God Mary and is bid farewell by Dante in a final prayer-like address. In their place for the final episode of the work a venerable old man, Saint Bernard of Clairvaux , as the author of the treatise De consideratione, possibly a source for Dante's theology of contemplation and vision, but here especially appreciated for its importance for the medieval veneration of Mary. to which he says a prayer in the name of Dante, after introducing him to the sky rose of the saints. The Paradiso closes with a glance from Dante into the eyes of Mary, who in turn, like all saints, looks to God, and finally, prompted by Bernhard, with the uplifting of his own eyes to an immediate vision of the Trinity .

The people of the Commedia

In the different areas of the other world, the visitor to the hereafter encounters a multitude of historical or historically presented mythological persons, in whom the respective type of their punishment, penance or bliss, according to the principle of retribution ( contrappasso ), reflects what they wanted in their previous earthly life, believed and did. People from ancient, biblical and, above all, medieval history, well-known and less well-known or sometimes (today) unknown, are presented as individuals with their personal passions, memories and shortcomings or merits, but at the same time make the ethically and theologically abstract Thought system on which the ranking of the afterlife districts is based.

The presentation of these people is narrative artfully and diversely varied and takes place partly in only brief mentions and catalog-like lists or in detailed encounter scenes in which the souls of the deceased hold a dialogue with the visitor to the hereafter and his guide and give him their memories of the past earthly life, messages to people who are still alive or to give prophecies about the future.

Form and title of the work

The commedia , in structure without a classical or biblical model, but with parallels in Avicenna's Ḥayy ibn Yaqẓān and more clearly in the treatment of the material by Abraham ibn Esra, which is also provided with biblical quotations (guidance of the narrator through a zone of fire, allegorical scene with pantheress (with Dante lonza ), lioness and she-wolf), is an epic - narrative telling of verses in rhyming eleven syllables , a total of 14,233 verses, which are rhymed according to the principle of terza rima , which is documented here for the first time, possibly invented by Dante himself , and in three books or Cantiche are divided into a total of one hundred (34, 33 and 33) chants ( canti ).

Although the title Commedia refers to the dramatic genre of comedy , it is not, or not strictly, to be understood in the sense of classical-ancient genre poetics. As the so-called dedication letter to Cangrande explains, it is based on the theme, language and style of the work: Thematically , it should characterize a work that begins in its treatment of a material with adverse things, here the repulsive horror of Hell, and becomes a happy one End, here the joys of paradise, leads to. With regard to the language , he should take into account the fact that the work is not written in Latin, but in the Italian vernacular, "in which women also converse" ("in qua et muliercule comunicant"). And with regard to the style , it should be justified by the fact that the work is not or not consistently written in a sublime style, but in a "loose and low" style ("remissus est modus et humilis") - while the text of the Commedia but actually all style registers, from the coarse obscene to the measuredly instructive to the hymnically ecstatic, united.

Dante also referred to the commedia in Paradiso as sacrato poema ('holy poem'), but the title epithet Divina ('divine') did not come from himself, but was only coined later by Boccaccio , as an expression of admiration for superhuman inspiration and poetic quality of this work. This epithet has been an integral part of the title in printed editions since the 16th century, while more recent critical editions have avoided the addition as a later addition.

Number symbolism

The three-part division of the work and the realms of the hereafter as well as the formal scheme of the three-verse terzines are traditionally related to the three as the number of the Trinity, while the number of 34, 33 and 33 chants, the first of which is often a prologue-like episode in A special position is seen, on the one hand also a reference to the threefold (3 × 33 chants and a prologue), but also a reference to the years of Jesus' life, since Jesus, according to one of the interpretations common in the Middle Ages, was 33 years old, before his 34th birthday ., Who died on the cross.

Also in the subdivision of the afterlife districts, which are described in the text as nine circles of the inferno (partly with further sub-districts), seven penitential districts of the purgatorio (together with the antipurgatorio and the garden of Eden also here nine areas) and (without including the empyrean) nine heavens of the Paradiso , numerous principles of order have been recognized, the interpretation of which is particularly supported in the Purgatorio and Paradiso by the fact that in the Purgatorio the penitential areas are assigned traditional schemes such as the catalog of the seven main sins and the Beatitudes of the Biblical Sermon on the Mount , while in Paradiso the nine heavenly spheres are assigned are assigned to the three by three choirs of angels .

Many attempts have been made to interpret numerous correspondences between the three parts of the work by comparing these areas of the hereafter and their upstream and downstream scenes, but also by taking into account the formal counting of the chants. In research there is agreement that the sixth chant of each cantica is deliberately dedicated to a topic of political history and that the sequence of topics (history of Florence, Italy and the Empire) also includes that often prevailing in the commedia Principle of gradual increase is true.

Even within individual chants or episodes, numerous principles of order are sometimes recognizable, in that a seemingly random sequence of anaphors , people or actions refers to a traditional numerical understanding that is informative for the topic currently being dealt with. However , there is still little agreement or certainty in research about such and further interpretations, which, particularly in the construction of verse numbers in the Commedia , want to trace back more complex numerical relationships to number-symbolic intentions or mathematical calculations by Dante.

Conditions of origin

At the time the Commedia was written, Dante had been in exile since 1302 as an exile from his hometown of Florence and stayed in various places in northern Italy, including Verona , Padua and Ravenna in particular . He relied on the support of princely patrons, but little or nothing is known about the conditions under which he lived and not only wrote his works, but also undertook the necessary studies.

Dante took a passionate interest in the political processes of his time, but no longer as an active politician, but primarily through his letters, writings and poems, with which he tried to influence what was happening. This commitment is also evident in the Commedia , but not just as a political one, but, as in all of Dante's works, as a very comprehensive endeavor to create a constitution for human society, which is based on the principles of the biblical plan of salvation, which are congruent for Dante orientated towards philosophical reason.

Contents of the three parts

The beginning of the journey to the hereafter

In the first person, the poet tells his journey through the three realms of the dead. The journey is said to have started on Good Friday in the year 1300. In the first song, the protagonist Dante got lost in a deep forest because he had lost the right path. Now the 35-year-old was striving towards the mountain of virtue when he saw a vision of animal shapes of a panther or a lynx (usually interpreted as a symbol of lust), a lion (the symbol of pride) and a she-wolf (the symbol of greed ) is pushed into a dark valley. There he meets the Roman poet Virgil , whom he admires and whom he immediately asks for help. Virgil replies to him as follows in front of the she-wolf, who looks angrily at Dante: "You have to go another way [...] if you want to escape from this wilderness." Dante is then accompanied by Virgil on a journey through hell and up the mountain of purification . When Aeneas wandered the hereafter, Virgil provided the literary model in the Aeneid to which reference is repeatedly made in the Commedia . Since Virgil comes from pre-Christian times and he was not baptized, entry into paradise is denied to him despite his righteousness. There on the Paradise Mountain, Dante is therefore led by his youthful sweetheart Beatrice , who died young and idealized . But this will also be discussed later by St. Bernhard replaced by Clairvaux .

1. Inferno / Hell

Hell is a funnel resembling an ancient amphitheater with steep terraces towards the center of the earth, created by the fall of Lucifer , which drove the Cleansing Mountain out of the sea in the southern hemisphere. The ten "circles" of hell (limbo and nine circles) are the places, points of view, horizons or characters in and because of which the repentance and purification of sinners, the good of the intellect ("il ben dell'intelleto") have lost.

In the upper hell, sinners out of excess (2nd – 4th circles) atone for sin , in the middle hell the sinners out of wickedness (5th – 7th circles), in the two lowest the sinners of betrayal (8th and 9th circles) ), whose high level of sin is explained by the fate of the author. First, chants and circles coincide, then circles with sub-circles appear, which are described in a part of a chant, in a whole chant or across several. Again and again the strong images, often used in world literature, the symbols of power and the princes of the Church, who are not to be expected here, surprise.

The hell sequence is a history book, a warning and literary retribution against Dante's opponents, with some critical insight also towards the politics of his own party. Both the open exposition of his own miserable situation and a later triumph of Dante over his opponents are the determining gestures. He puts the idea of reckoning with the enemy z. B. in the mouth of sinners who were themselves victims of other perpetrators: "But my word serves as a seed, from which shame sprouts the cheeky traitor, which I eat here." The souls in purgatory hope that it will spread the truth among the living or exhorting loved ones to zealous intercession for their poor souls.

God's righteousness, in whose name the eternal torture and torment of hell and its limited forms in purgatory are carried out, is an appropriately punitive, “just” compensation for the sins of the living. The construction principle of their punishments is an ironic reversal (contrappasso) of their vices and crimes, a belated irony of history: greedy - clinging to things - push boulders on forever, violent criminals have to hide in a boiling bloodstream from the centaurs bombarding them, Flatterers sit in the cesspool, fortune tellers wear their faces on their backs - now forever facing the past, hypocrites drag gilded robes made of lead on the outside, dissidents are chopped up again and again by devils, traitors - always speculating on a sudden turn in history - lie frozen in the ice lake Cocytus, the deepest circle of hell.

First through fifth chants

According to Dante's view of the world, hell lies in the interior of the northern hemisphere. It is the seat of Lucifer and consists of circles tapering towards the center of the earth. The funnel was created by the fall of Lucifer and his angels, and the earth pushed back in this way forms the Purification Mountain , which is the only land mass that protrudes from the southern hemisphere, which is otherwise covered by water.

“Through me one goes into the city of mourning,

through me one goes into eternal pain,

through me one goes to the lost people.

Justice drove my high creator,

the omnipotence of God created me, the

highest wisdom and the first love

There was no created thing before me,

only eternal, and I must last forever.

Let go of all hope, you who enter! "

Beyond the gates of hell lies limbo, the place for the lukewarm souls who were neither good nor bad. These run around restlessly in droves and are tormented by vermin. At the first river of hell, the Acheron , the evil souls gather, who are brought to the other bank by Charon . Here Charon refuses the poet the passage with a dark allusion to his eternal fate. How Dante ultimately crosses the Acheron remains in the dark.

On the other side of the Acheron awakened from deep swooning, Dante howls from the depths of the hell funnel towards humanity in complete misery. Then he steps down with Virgil into the silence of the first circle of hell, clouded only by sighs. Here, in limbo , there are those who have become innocently guilty, all those who are free of sin, but do not belong to the Christian faith (or are not baptized), but are only tormented by eternal longing. Not only unbaptized children can be found in this circle, but also poets and thinkers of antiquity and paganism. In addition to the ancient poets such as Homer , philosophers such as Aristotle , the Trojan and Roman heroes, but also medieval figures such as Averroes , Avicenna and Sultan Saladin , Virgil is also one of those who lived under false, lying gods . After the ancient hero show, during which the two poets are accompanied by Homer, Horace , Ovid and Lukan , Dante descends further with the Roman poet.

Behind the first circle of hell, the sinners are received by the ancient Hades judge Minos , here distorted into a demon. Before this they must confess all of their sins. The connoisseur of all sins determines with the help of his tail into which circle the person concerned must descend. Like Charon before, Minos must first be appeased by Virgil. In the second circle, the voluptuous who are chased around by the infernal storm atone. There Dante meets Semiramis , Cleopatra , Dido , Achilles , Helena , Paris and several knights. In the fifth song we encounter the adulterous lovers Paolo and Francesca da Rimini , whose fate inspired numerous works of music and the visual arts: Seduced by the joint reading a book in which Lancelot Queen Guinièvre kisses, Francesca had given her brother Paolo and had been caught and killed by her husband with her lover. Dante collapses out of pity for her temporal and eternal fate.

Sixth through eleventh chant

In the third circle of hell, Dante meets the souls of the voracious, who lie on the ground in the icy rain and are guarded and tortured by the hellhound Kerberos - here a symbol of voracity. One of the souls, a Florentine named Ciacco, foretells Dante future events that will affect Florence.

In the fourth circle of hell are the spendthrifts and the stingy, who are guarded by Plutos . The sinners rage, rolling burdens with the force of their shoulders as they bump against each other. The fifth circle of hell is the swamp of angry souls. Choleric fighters relentlessly fight each other in the floods of the Styx river , while ignorant and phlegmatic people stay forever submerged in the floods of the Styx. A fire alarm is given from a tower on the river bank, whereupon the ferryman Phlegyas appears and translates the poets. In the encounter with the choleric Filipo Argenti, Dante consciously repels evil for the first time.

Even during the boat trip, the poets see the hell city of Dis on the other bank . Legions of devils prevent the two hikers from entering. After meeting the Erinyes and the three Gorgons , an angel appears and came to the gate, and with a twig he unlocked it . It becomes clear that Dante's journey has the blessing of God to be led back on the right path. In the sixth circle the heretics atone in flaming coffins, which will close after the judgment in the valley of Jehoshaphat. One of the condemned here, the Ghibelline Farinata degli Uberti, foretells Dante's banishment and explains to the poet that the condemned can indeed see into the future, but know nothing of the present if nothing is communicated to them by newcomers.

In the shadow of the tomb of Pope Anastasius II, the poets rested to get used to the stench rising from the depths. Virgil uses the rest to explain to Dante the structure of lower hell: the seventh circle of hell belongs to the violent, the eighth and ninth circles belong to wickedness - separated from one another as general deception, which finds retribution in the eighth circle, and as deception in a special relationship of trust (treason), which is punished in the ninth circle on the bottom of hell. Dante asks why the inhabitants of the second to fifth circles are punished separately, to which Virgil refers to the differentiation of immensity, confused animal instinct and malice through Aristotelian ethics.

Twelfth to seventeenth chants

The seventh, eighth and ninth circles form the inner hell, the entrance of which is guarded by the Minotaur of Crete. The worst sins are punished here: violent crimes, fraud and treason.

But because you can hurt three people, the seventh circle is divided into three rings. In the first ring, acts of violence against the neighbor are atoned for. Murderers, robbers and devastators boil in a blood stream into which they are repeatedly driven back by centaurs when they try to get more out of it than their guilt allows. Depending on the severity of their deed, they are immersed in the bloodstream to different depths. Alexander the Great and the tyrant Dionysius are up to their brows in the river, while Attila is tormented at the bottom. One of the centaurs, Nessos , carries Dante across the bloodstream at the behest of his companion Cheiron .

Suicides (including Pier delle Vigne , Frederick II's Chancellor ) are guilty of their guilt in the second ring. They have to eke out their existence as bushes and trees that are repeatedly disheveled by the harpies , because they have torn themselves away from their bodies with their suicide - because what you have taken from yourself is not allowed to have . On their way through the suicidal bushes, the two poets meet two souls who have squandered their possessions piece by piece in their lives and are chased through the thicket by black hellhounds and torn apart piece by piece. Stierle interprets this passage biographically:

“For Dante, if you will, a whole world collapses at the moment of exile. He is losing his political identity, he is losing his civic existence, he is losing his family and he wonders whether he really is to blame for all of this. And then the question arises about God's righteousness and thus also about the meaningful structure of the whole world, of which he is desperate, so very desperate that, I think, he is on the verge of suicide, and that actually with the picture of the dark forest as an image for the suicide the commedia begins . "

Those who have committed violence against God (blasphemy), against nature (sodomy) and against art (usury) pay in the third ring, the bottom of which is made of sand. The blasphemers lie stretched out and screaming on the ground, the sodomites run around without rest and peace, the usurers crouch on the abyss where the third hellish river Phlegethon pours down into the eighth circle, idly with their money bags, and flakes of fire constantly trickle down on everyone . Here Dante meets the blasphemer Kapaneus , but also his former teacher Brunetto Latini and three Florentine officers.

All in all, references to the politics of the poet's hometown are increasingly discussed in these chants, seen from a spatial and temporal distance.

Eighteenth to thirtieth chant

On the slope of the Phlegethon they see the mythological figure Geryon . Dante looks at the monster with astonishment and describes it as follows: ". Here the monster comes with a pointed tail, takes the mountains and walls breaks and weapons, here it comes, the verstänkert the whole world" , the eighth circle of hell (Malebolge) in ten Divided trenches. In the first, the matchmakers and seducers (among the latter the figure of Jason ), driven by horned devils with whips, drag themselves through the ditch in return. Flatterers and whores wallow in caustic excrement in the second ditch.

In the third trench, the Simonists, swindlers who drove lively trade with church offices, are stuck upside down in rock holes from which only their burning soles protrude. Like a confessor, Dante speaks to the soul of Pope Nicholas III. who believes that his successor Boniface VIII has already arrived in hell. He also prophesies the arrival of Clement V as a sinner. Dante harshly criticizes the trade in church offices, which promotes the secularization of the church.

In the fourth trench, Virgil and Dante observe the magicians and fortune tellers, whose bodies have been twisted so that their faces are turned backwards - namely, their faces are turned to their backs . In addition to several women who were addicted to sorcery (including the mythical Manto , from which Virgil's birthplace Mantua got its name, as Virgil himself reports in detail), Amphiaraos and Teiresias , famous seers of antiquity, but also contemporaries like Guido Bonatti, spend their time there To be there.

The fifth trench is filled with boiling pitch in which the bribed penance. A special group of devils, the painting industry , fetches their souls and guards them: Those who stick their heads out of the flood of bad luck are pulled ashore with forks and beaten there. Dante and his companion manage to escape the devils and get into the sixth trench. There the hypocrites have to walk in heavy gilded lead coats. Suffering from their kicks, the crucified councilors of the Pharisees lie on the ground, including Kajaphas , who hypocritically advised Jesus Christ to be killed for the good of the state before the Jerusalem council meeting.

In the seventh trench, thieves and robbers are constantly attacked by snakes, whose bites make them crumble to ashes, only to have to rise again soon afterwards - the eternal punishment of thieves. Not all sinners are merely bitten by the snakes, others merge with them (or a dragon) into a monstrous monster. Insidious advisers and deceitful robbers atone by floating through the eighth trench, wrapped in flames like fireflies. Here Dante speaks with Odysseus , who has to atone with Diomedes for the ruse by which Troy was brought down, as well as with the former Ghibelline leader and later Franciscan Guido da Montefeltro, who himself for his deceptive advice to Pope Boniface VIII. , Palestrina to break has betrayed his eternal salvation. In the ninth ditch, Dante encounters those who split the faith and create discord, including the founder of Islam , Mohammed , and his son-in-law Ali . A devil incessantly cuts off limbs and deep wounds - they were the originators of bickering and discord / In life, that's why they're so divided . In the last trench of the eighth circle of hell, the forgers, alchemists and false witnesses suffer from disgusting diseases and fall upon each other in a blind frenzy. Among them are Potiphar's wife , whom Joseph slandered, and Sinon of Troy.

Thirty-first through thirty-fourth chants

Giants rise like towers (Virgil names Nimrod , Ephialtes , Briareus , Tityus and Typhoeus ) at the edge of the ninth circle of hell. At Virgil's request, Antaeus sets the two hikers down at the bottom of the last circle of hell. There the traitors atone, frozen up to their heads in a lake: in the Kaina the traitors to relatives and in the Antenora the political traitors. The traitors to table mates are frozen backwards in the Tolomea , so that their eyes, which have become crystals, close forever. The souls of sinners in this zone can be separated from their bodies while they are still alive. A demon then slips into the lifeless shell and is up to mischief in the world. In the lowest depths of hell, the Judecca , lie completely covered by the ice those sinners who have betrayed their Lord and benefactor. And in their midst is the fallen Lucifer in the ice, crushing the arch traitors Judas , Brutus and Cassius in his three mouths .

Virgil takes Dante and grabs the shaggy fur of Satan, on which he first climbs down between Satan and the ice wall and, since they are in the center of the earth, also climbs up: The way out is only possible through Satan himself. Virgil finds a hole in the rock that they can step into, and they enter a new hemisphere via a corridor. Dante is insecure and Virgil replies: They crawled on Satan's fur through the center of the earth, the ice is gone, East and West, above and below have now been swapped. You get back to the world of light, to the stars, via a path along a stream .

2. Purgatorio / The Cleansing Mountain

The Cleansing Mountain or Purgatory is laid out as a circular path around a mountain that begins behind a gate and gradually screws itself towards the light. Souls atone for seven terraces - together with the sea fringe guarded by Cato and the adjoining area for those who fail, there are nine steps here too.

Compared to the desolation of hell, repentance and hope of sinners now dominate. The ironic reversal still rules the punishments, which are finite (even if they last 500 years or more): In purgatory or on the Cleansing Mountain, the haughty under the weight of stones can no longer take their eyes off the ground, the envious ones became the eyes sewn shut with wire, the lazy ones have to rush around the mountain, the greedy ones lie with their faces in the dust of the path ...

In front of the gate of the Cleansing Mountain, the guarding angel with his sword draws seven P (ital. Peccato "sin") on Dante's forehead for the 7 deadly sins (arrogance, irascibility, envy, greed, lust, gluttony and indolence), of which he is himself got to clean. Only then does the guard unlock the gate, Dante begins his own penance on the way to the light and seeks to free himself from false passions, especially from his arrogance .

The terraces of the Purification Mountain

On the first three terraces, souls are purified with a love of vice.

- First terrace: On the first terrace, the proud suffer by having to carry huge stones on their backs without being able to stand up. This is to teach them that pride lays weight on the soul and should therefore be discarded. Engraved on the floor are historical and mythological examples of pride. Bent over by the weight, sinners are compelled to study them in order to learn from them. On the ascent to the next level, an angel appears and removes a P from Dante's forehead. This is repeated on every ascent. With each removal, Dante's body feels lighter as less sin is holding it down.

- Second terrace: The envious are purified on the second terrace by having to wander around with their eyes sewn shut. At the same time they wear clothes with which their soul is indistinguishable from the ground. This is to teach sinners not to envy others and to guide their love for God.

- Third terrace: On the third terrace, the angry must walk around in the sour smoke. They learn how anger blinded them and diminished their judgment.

- Fourth terrace: on the fourth terrace are the sinners of lack of devotion, of indolence. The lazy people are forced to run constantly. They can only experience purification by restlessly repenting.

- Fifth Terrace: On the fifth terrace to the seventh terrace are the sinners who have loved worldly things in a wrong way in their life. The greedy and the spendthrift lie facedown on the ground and cannot move. The exaggeration of worldly goods is purified and sinners learn to direct their desire for possessions, power or high positions towards God. Here Dante meets the soul of Statius , who has completed his purification and accompanies Dante and Virgil on their ascent to paradise.

- Sixth terrace: On the sixth terrace, the immoderate must experience refinement in constant abstinence from eating and drinking. This is made more difficult for them by the fact that they have to pass cascades without being able to drink.

- Seventh Terrace: The voluptuous are purified by burning in a huge wall of flames. Here the sexual excesses that divert the love of sinners from God are to be overcome. All sinners who have repented on one of the lower terraces must also pass through the wall of flames on the seventh terrace before they can leave the mountain of cleansing. After Dante shares this lot, the last P is removed from his forehead.

3. Paradiso

The angelic Beatrice leads Dante through the nine heavenly spheres of paradise. These are concentric and spherical, as in the Aristotelian and Ptolemaic worldview. While the structures of the Inferno and Purgatorio are based on different classifications of sin, the Paradiso is structured by the four cardinal virtues and the three theological virtues . Dante meets and speaks with several of the Church's great saints, including Thomas Aquinas , Bonaventure , Saints Peter and John.

The Paradiso has more theological nature as hell and purgatory. Dante admits that the vision of heaven he describes is the one he was allowed to see with his human eyes.

Dante's Divine Comedy ends with the sight of the Triune God . In a flash of knowledge that cannot be expressed, Dante finally understands the mystery of Christ's deity and humanity, and his soul becomes connected with the love of God.

Résumé

Without exception, Dante's work is rated as "epochal": it contains, for the first time in the Italian vernacular "ennobled" by Dante, the three-part journey through "the empire after death", as it was seen around 1300: first down to "hell", then up through the “Purgatorio”, then into “Paradise”; the whole thing in epic form, which was appropriate to the high standard.

The work explicitly refers to the great verse drama Aeneid by the Roman poet Virgil and thus makes extremely high demands from the start. These claims are indeed met, especially since Dante not only repeatedly takes up details of the entire political life of Italy from the late Staufer period of the 11th century to the time of the early Habsburgs and Emperor Henry VII from the House of Luxembourg . These details require sparing commentary so that they are understandable for readers of the present day and at the same time the "tone" of the original is preserved.

With his recourse to forms of antiquity, Dante contributed to the fact that the Renaissance was able to develop in Italy very early instead of the Gothic art style .

Not only in the theological worldview is Dante's work - apart from the overwhelming poetic dimension - fully at the height of the knowledge of his time. So he links z. B. in the closing verses of his work explicitly the difficulty of understanding the Trinity of God with the mathematical problem of the tripartite division of an arc .

Reception history

Visual arts

Illustrations and paintings

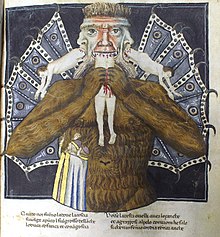

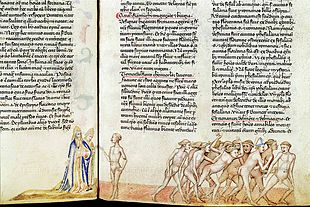

Dante's Commedia has exerted an extraordinary influence on works of fine art as well. Illustrations started in the manuscripts of the Commedia already a few years after his death, the oldest dated illustrated manuscript is the Codex Trivulzianus No. 1080 from 1337 in Milan, possibly a few years earlier (around 1330?) The 32 illuminations in the so-called Poggiali Codex ( Florence, BNCF , Palat. 313). In some churches, especially in Florence, paintings resembling images of saints were created in the 15th century.

The formative influence was also noticeable early on in independent works of art, in particular depictions of Hell and the Last Judgment, although it is not always clearly distinguishable from older literary and iconographic traditions. Dante's influence in the frescoes of Camposanto in Pisa (by Buonamico Buffalmacco ?) Is also indicated by inscribed quotations as early as 1340 , while Francesco da Barberino's book of hours ( Officiolum ) , created between 1306 and 1309 , in whose illustrations one also believed to be able to recognize the iconographic influence of the Inferno , is probably not yet an option due to its early creation.

An artistically outstanding position among the illustrations of the 15th century are the drawings for all three 'Cantiche' of the Commedia , which Sandro Botticelli created since 1480, but no longer completed them, of which 93 pieces have been preserved, which are still in existence today distributed between the Kupferstichkabinett Berlin and the Vatican Library in Rome. They also formed the template for the woodcuts that Baccio Baldini produced for the first print edition of the Dante commentary by Cristoforo Landino (1481), and due to the enormous success of this commentary, they also left their mark on the illustrations in subsequent Dante editions.

Further examples for the illustration of the commedia and for its reception in the visual arts:

A large number of drawings created around 1580 by Jan van der Straet (Johannes Stradanus) , Federico Zuccaro and Jacopo Ligozzi have been viewed as related commissioned work by a Florentine printer for a planned edition of the Commedia , a thesis which, however, after the Findings from recent research are unsustainable.

In the 18th century, the illustrations by the British artist John Flaxman were very common in Europe, they are characterized by a minimalist style of representation. Achim von Arnim comments in a letter to Jacob and Wilhelm Grimm : “Only now can I explain to myself why Flaxmann's drawings are usually as empty as images of regimental uniforms, mostly nothing other than the officer Virgilius and a common man, Dante march one behind the other. "

The most famous illustrator of the Divine Comedy in the 18th century was Joseph Anton Koch , who created numerous drawings and paintings as well as the famous frescoes on Hell and Purgatory in the Casino Massimo in Rome.

In 1822, the French romantic Eugène Delacroix painted a painting called The Dante Barque (originally La Barque de Dante or Dante et Virgile aux enfers ), which is now in the Louvre . It shows Dante and Virgil as well as the sinner Filippo Argenti crossing the Styx . (See Inf.Canto VIII.)

The English poet and painter William Blake planned and created several watercolors for the Divine Comedy . Although the cycle was unfinished when he died in 1827, they are still among the most impressive interpretations of the work today.

In 1850 the artist William Adolphe Bouguereau painted a painting: Dante And Virgil In Hell .

Gustave Doré , who tried to illustrate the Divine Comedy at the age of nine , created numerous wood engravings in 1861 . These are among the most famous illustrations of the work today. In addition, he also painted a painting entitled Dante et Virgile dans le neuvième cercle de l'enfer , which shows Dante and Virgil in the ninth circle of hell.

Anselm Feuerbach painted the painting of the lovers Paolo and Francesca in 1864 .

Gustav Klimt created the picture Old Italian Art in the stairwell of the Kunsthistorisches Museum in Vienna in 1891 , the content of which was inspired by the Divine Comedy .

Franz von Bayros , best known for his erotic drawings, illustrated the work in 1921.

In the middle of the 20th century, Salvador Dalí designed a picture cycle for the Divine Comedy .

In 1975 the British artist Tom Phillips was commissioned to illustrate the Inferno . He translated Dante's text into English and over a period of about seven years he created 139 illustrations for Dante's Inferno (artist book Talfourd Press 1983, Thames & Hudson 1985). Phillips' illustrations provide a very personal visual commentary that carries the medieval text into the 20th century.

By Robert Rauschenberg , a series of 34 drawings comes to the Inferno , which he age of 35, the age when Dante with the Commedia , ranging began and where he has worked for 18 years. Rauschenberg uses his very own technique, such as frottage of photos moistened with turpentine, which are put together as a kind of collage on 36.8 × 29.2 cm Strathmore paper and create the effect of a drawing. Images of Adlai Stevenson, John F. Kennedy, ancient statues, baseball referees or simply the letter V can serve as templates for Dante and Virgil. The drawings are often divided into three parts and correspond to the three-part division of the meter used by Dante, the terzines . On closer inspection, Rauschenberg's illustrations turn out to be very close to Dante's text; indeed, they only become apparent to the viewer when reading them.

Between 1992 and 1999 the German artist Monika Beisner illustrated all 100 cantos of the Divine Comedy . This makes her one of the few who have implemented the entire comedy in a painterly manner and the first woman to have taken on the illustration of the work. In doing so, she transcribed Dante's 100 chants as detailed and as literally as possible in pictures, painted with egg tempera paints. Editions of works with Beisner's pictures have been published in German, Italian and English.

The South Tyrolean artist Markus Vallazza created numerous illustrations (300 engravings, 9 illustrated books and around 100 paintings) for the Divine Comedy between 1994 and 2004 . Miquel Barceló created an extensive book illustration on the Inferno in 2003 , which was published in both Spain and Germany.

Sculpture and architecture

The sculptor Auguste Rodin worked for almost 37 years on the "Hell Gate", a bronze portal for the Musée des Arts Décoratifs in Paris, where he was mainly inspired by the Divine Comedy . Even if it was never originally executed, this work can be described as Rodin's main work because of its numerous sculptures isolated from it (e.g. The Thinker , which depicts Dante Alighieri).

In 1938 Giuseppe Terragni designed a “Danteum” on Via dell'Impero, today's Via dei Fori Imperiali in Rome. As built architecture of Dante's vision of the unification of Italy, the design from 1938 was also intended to glorify the re-establishment of the Italian Empire by Mussolini. However, the development of the war prevented the execution.

The Palacio Barolo in Buenos Aires, built by the Italian architect Mario Palanti between 1919 and 1923, was designed in harmony with the cosmos as described in Dante Alighieri's Divine Comedy . The 22 floors are divided into three sections. The basement and the first floor represent hell, floors 1 to 14 represent purgatory and 15 to 22 represent heaven. The height of 100 meters corresponds to the 100 songs of the Divine Comedy .

Movie

Between 1909 and 1911, the Divine Comedy was filmed in Italy in three parts. The directors of the silent film were Francesco Bertolini and Adolfo Padovan. In 2004 the film was released in a DVD version under the title L'inferno .

In 1985, Peter Greenaway and Tom Phillips shot a 15-minute pilot film for a planned series: A TV Dante , which was not revised until three years later and supplemented with additional Canti (I – VIII). A TV Dante was named “Best experimental video of 1990” at the Montreal International Film and Video Festival in 1990 and the Prix d'Italia in 1991. In 1989, the Chilean director Raúl Ruiz shot six more chants, also known as Diablo Chile .

An adaptation is also found in the US drama behind the horizon in 1998, in which the roles of Dante and Virgil with changed names with the actors Robin Williams and Cuba Gooding, Jr. embodied. The plot is shifted to the present and changed, but unmistakable scenes, for example the journey across the river of the dead, are clearly to be seen as an adaptation of the original.

In 2010, an anime version was released under the title Dante's Inferno: An Animated Epic . This story is loosely based on Dante's poem and describes Dante as a fallen crusader who tries to free his beloved wife Beatrice from Hell while dealing with his own sins and their consequences that led to Beatrice's death.

In 2016, the documentary Botticelli Inferno was shot as a German-Italian production in high-resolution 4K format via the "Mappa dell'Inferno".

music

- Franz Liszt wrote a Dante symphony for female choir and orchestra. It consists of two movements: Inferno and Purgatorio , the latter ending with the beginning of the Magnificat .

- Peter Tchaikovsky wrote a symphonic fantasy Francesca da Rimini about an episode from the Inferno part of Dante's work. This material is also the basis for the opera Francesca da Rimini by Sergej Rachmaninow and Francesca da Rimini by Riccardo Zandonai (based on a libretto by Gabriele D'Annunzio ).

- Max Reger is said to have written his Symphonic Fantasy and Fugue for organ under the impression of reading Dante's work. Hence it is often called the inferno fantasy .

- Giacomo Puccini 's opera Gianni Schicchi - the third part of his Trittico - also relied on an episode from the Inferno part.

- Felix Woyrsch set to music in his Symphonic Prologue to Dante's Divina commedia , op. 40, Dante's journey through the inferno to paradise.

- The Russian composer Boris Tishchenko composed a cycle of five symphonies between 1996 and 2005, which programmatically refer to Dante's Divine Comedy and can also be performed as a ballet.

- The multimedia opera project COM.MEDIA by the Austrian composer Michael Mautner dramatizes the Divine Comedy as a contemporary theme in a prelude and three parts ( Inferno , Purgatorio and Paradiso ) through music, reading, song, dance, video technology and electronics.

- The name of the minimal electronics band Nine Circles (in German: nine circles) comes from the nine circles of hell that Dante Alighieri describes in his Divine Comedy.

- The German metal band Minas Morgul used the Dante theme in the song Opus 1 - Am Höllentore , the first song on the album Schwertzeit , released in November 2002 . On March 17, 2006, the Brazilian metal band Sepultura released the album Dante XXI, which takes up the content of the Divine Comedy and projects it onto the 21st century. The song Dante's Inferno by the American metal band Iced Earth is also about the Divine Comedy . Mick Kenney of Anaal Nathrakh was inspired by the Divine Comedy for the debut of his solo project Professor Fate , The Inferno , which he released on FETO Records in 2007 .

- The American composer and arranger Robert W. Smith also wrote a symphony for wind orchestra entitled The Divine Comedy (Symphony No. 1).

- In 2003, Bayerischer Rundfunk, together with Hessischer Rundfunk, produced a radio play in which the musician Blixa Bargeld made a significant contribution.

- Metal band Five Finger Death Punch released an instrumental called Canto 34 .

- Edgar Froese composed a trilogy comprising three double CDs ( Inferno , Purgatorio and Paradiso ) for his electronic group Tangerine Dream , which was inspired by Dante's Divina Commedia .

- The songwriters joint venture released the song The Divine Comedy in 1995 on the album Augen zu .

- The American metal band Alesana released their album A Place Where the Sun Is Silent on October 18, 2011 , which is about Dante's Inferno .

- A song from the first album by the metal band Luca Turilli's Rhapsody is called Dante's Inferno .

- The Divine Comedy is the subject of the 1997 debut album Komödia by the Austrian symphonic metal band Dreams of Sanity .

Literature citations and reminiscences

- Peter Weiss ' novel The Aesthetics of Resistance is significantly influenced by the Divina Commedia , which is one of the main works of the more than one hundred works of art included . On the one hand it is introduced and discussed directly by the protagonists in the narrative, on the other hand it is also processed in numerous motifs, allusions and mythical derivations. The play The Investigation , written by the same author, is also based on the Divine Comedy .

- In the novel Guardian of the Cross (original title: El último Catón ) by Matilde Asensi , the Divine Comedy plays a central role as a guide through a series of difficult tests that the protagonists have to pass.

- In the detective novel The Seventh Level (English original title: The Savage Garden ) by Mark Mills from 2006, the Divine Comedy is the key to understanding the concept and message of a Renaissance garden in Tuscany.

- The allegorical novel GLIBBER bis GRÄZIST by Florian Schleburg , published in 2011 under the pseudonym Siegfried Frieseke, represents in its structure and numerous motifs a transfer of Divina Commedia into the 21st century; the three-part structure of the novel is based on the commedia .

- In Dan Brown's novel Inferno , the Divine Comedy also plays a central role.

- In his autobiographical novel Inferno , August Strindberg processes his psychotic phases as a journey into hell based on Dante.

- The British Malcolm Lowry enforced his 1947 novel Unter dem Vulkan (which had been created as the first of three parts of a novel project) with many allusions to the Divina Commedia . In the reverse of the first Canto in the Divina Commedia , the alcohol-addicted protagonist in Unter dem Vulkan is killed at the end in a forest.

- Joseph Conrad's 1899 novel Heart of Darkness is also peppered with allusions to the inferno . The protagonist's journey along the Congo River into the eponymous heart of darkness seems like a journey into hell.

- In Primo Levis is that a human? In the Auschwitz extermination camp, the protagonist rediscovers the verses of the Commedia , still known to him from school , and tries with their help to bring the Italian language closer to a fellow prisoner. The protagonist is particularly impressed by the admonition of Odysseus imprisoned in hell (beginning with “Considerate la vostra semenza”).

- The work of Ezra Pound , who wrote his poems based on Dante Cantos , and that of TS Eliot , especially his long poem The Waste Land , contain many allusions to the Divina Commedia .

- Samuel Beckett , whose favorite books included the Divina Commedia , named the alter ego in his early works Dream of more to less beautiful women and More beatings as wings after the lethargic figure Belacqua crouching in purgatory.

- In her novel Das Pfingstwunder, Sibylle Lewitscharoff describes a congress of Dante researchers who disappear through a kind of "Ascension" during a congress on the Divina Commedia . Only the 34th participant ("the surplus") remains behind.

- The Iranian-Canadian author Ava Farmehri uses the suicide quote as the title of a book about her exile: Our bodies will hang in the dark forest. Nautilus publishing house, Berlin. Übers. Sonja Finck ( Through the Sad Wood Our Corpses Will Hang, Guernica books, Oakville 2017).

Comic

In the Marvel Comics , the X-Men travel through a magical facsimile of the hell described in the Inferno to save their teammate Nightcrawler from punishment for an alleged murder that later turned out to be self-defense ( X-Men Annual # 1, 1980).

The Francesca da Rimini episode from Canto 5 served as a model for a Disney comic: In the story The Beautiful Francesca (Funny Paperback 88), Daniel Düsentrieb plays Dante as he is currently writing his Divine Comedy .

Seymour Chwast adapted the Divine Comedy as a comic and drew it in 2010 . The German edition was published in 2011.

Another adaptation was published in February 2012 by Michael Meier with the title Das Inferno .

Guido Martina (copywriter) and Angelo Bioletto (draftsman) have created a parody of Dante's Inferno with the title Micky's Inferno (Original: L'inferno di Topolino ). Mickey Mouse takes on the role of Dante and Goofy that of Virgil. The story appeared from 1949 to 1950 in Topolino volumes 7 to 12. In Germany the story was published in Disney Paperback Edition 3.

computer game

In 2010 Electronic Arts released the video game Dante's Inferno .

expenditure

- Italian ( La Comedia ):

- 14th century: Codex altonensis

- 1472: First printing by Johannes Numeister in Foligno or by Georg and Paul (von Butzbach) in Mantua

- 1481: First Florentine edition, with drawings by Sandro Botticelli , engraved by Baccio Baldini

- Complete German translations of the Divine Comedy in chronological order according to the publication date of the final volume:

- 1767–69: Lebrecht Bachenschwanz (prose)

- 1809–21: Karl Ludwig Kannegießer ( terzines with predominantly female rhymes )

- 1824–26: Carl Streckfuß (Terzinen with regularly alternating male and female rhymes)

- 1830–31: Johann Benno Hörwarter and Karl von Enk (prose)

- 1836–37: Johann Friedrich Heigelin ( blank verses with a male closure throughout )

- 1840: Karl Gustav von Berneck (Bernd von Guseck) (terzines with predominantly female rhymes)

- 1837–42: August Kopisch (blank verses with almost entirely female closure)

- 1828; 1839–49: Philalethes, pseudonym of Johann von Sachsen (blank verses with almost entirely female endings)

- 1864: Ludwig Gottfried Blanc (blank verses with predominantly female closure)

- 1865: Karl Eitner (blank verses with predominantly female closure)

- 1865: Josefine von Hoffinger (modified Schlegel terzines, rhyme scheme [aba cbc ded fef ghg ihi ...]; the outer terzines are consistently feminine, the middle verses consistently masculine)

- 1865: Karl Witte (blank verses with predominantly female closure)

- 1870–71: Wilhelm Krigar (terzinen with female rhymes throughout)

- 1871–72: Friedrich Notter (terzines with regularly alternating male and female rhymes)

- 1877: Karl Bartsch (terzines with predominantly female rhymes)

- 1883–85: Julius Francke (terzines with female rhymes throughout)

- 1888: Otto Gildemeister (Terzinen with regularly alternating male and female rhymes)

- 1889: Sophie Hasenclever (Terzinen with regularly alternating male and female rhymes)

- 1887–94: Carl Bertrand (blank verses with predominantly female closure)

- 1901: Bartholomäus von Carneri (blank verses with roughly balanced male and female closure)

- 1907: Richard Zoozmann [I] (Terzinen with predominantly female rhymes)

- 1908: Richard Zoozmann [II] (Schlegel terzines with almost all female rhymes)

- 1914-20: Lorenz Zuckermandel (Terzinen with predominantly female rhymes)

- 1920: Axel Lübbe (terzinen with almost all female rhymes)

- 1892–1921: Alfred Bassermann (terzines with predominantly female rhymes)

- 1921: Konrad Falke (blank verses with clearly predominantly female closure, including many spondes)

- 1921: Hans Geisow (mixed rhyme forms, strongly oriented towards Goethe)

- 1926: August Vezin (terzinen with almost all female rhymes)

- 1922–28: Konrad zu Putlitz , Emmi Schweitzer, Hertha Federmann (terzines with regularly alternating male and female rhymes, terzines with predominantly female rhymes)

- 1928: Georg van Poppel (terzinen with almost all female rhymes)

- 1929: Reinhold Schoener (blank verses with almost entirely female closure)

- 1923; 1930: Rudolf Borchardt (terzines with predominantly female rhymes)

- 1937: Friedrich Freiherr von Falkenhausen (terzines with slightly predominantly female rhymes)

- 1942: Karl Vossler (blank verses with roughly balanced male and female closure)

- 1949–51: Hermann Gmelin (blank verses with female closure throughout)

- 1952: Hermann A. Prietze (blank verses with slightly predominantly female closure)

- 1955: Wilhelm G. Hertz (terzinen with alternating male and female rhymes)

- 1955: Karl Willeke (Sauerland Low German; blank verse with female endings throughout)

- 1960–61: Benno Geiger (terzines with female rhymes throughout)

- 1963: Ida and Walther von Wartburg (blank verse with slightly predominantly female closure, but also multiple six-lifter , occasionally a four-lifter )

- 1966: Christa Renate Köhler (terzines with roughly balanced male and female rhymes)

- 1983: Hans Werner Sokop (terzines with female rhymes throughout)

- 1986: Nora Urban (mostly blank verses with male and female closures; multiple six-lifter and four-lifter)

- 1995: Georg Hees (Prose Concordance IT / D)

- 1997: Hans Schäfer (terzinen with female rhymes throughout; multiple six-levers; occasionally trochaic verses)

- 1997: Georg Peter Landmann (prose)

- 2003: Walter Naumann (prose)

- 2004: Thomas Vormbaum (terzinen with end rhyme)

- 2010: Hartmut Köhler (prose) Inferno, 2011 Purgatorio, 2012 Paradiso

- 2011: Kurt Flasch (prose)

- 2014: Hans Werner Sokop (Terzinen with female rhymes throughout), new edition

- Partial translations:

- 1763: Johann Nikolaus Meinhard (prosaic partial translation of sections from the Inferno , Purgatorio and Paradiso )

- 1780–82: Christian Joseph Jagemann (only the inferno )

- 18xx: August Wilhelm Schlegel (partial translation of sections from the Inferno , Purgatorio and Paradiso )

- 1843: Karl Graul (only the inferno )

- 1909, 1912: Stefan George (partial translation of sections from the Inferno , Purgatorio and Paradiso )

- retelling prose version of the complete work:

- 2013: Kilian Nauhaus

- Further translations:

- 1515: Commedia. Burgos (Spanish)

literature

Critical Editions

In German language

- Karl Witte : La Divina Commedia di Dante Alighieri, ricorretta sopra quattro dei più autorevoli testi a penna. Rudolfo Decker, Berlin 1862.

In Italian

- Dante Alighieri: La Divina Commedia, testo critico della Società Dantesca Italiana, riveduto col commento scartazziniano, rifatto da Giuseppe Vandelli. Milan 1928 (and reprints to the present day).

- Dante Alighieri: Divina Commedia, Commento a cura di G. Fallani e S. Zennaro. Roma 2007.

Introductory explanations and research literature in general

- Erich Auerbach : Dante as a poet of the earthly world. With an afterword by Kurt Flasch, Berlin 2001.

- John C. Barnes / Jennifer Petrie (Eds.): Dante and the Human Body. Eight Essays, Dublin 2007.

- Teolinda Barolini: Dante and the Origins of Italian Literary Culture. New York 2006.

- Susanna Barsella: In the Light of the Angels. Angelology and Cosmology in Dante's 'Divina Commedia'. Firenze 2010.

- Ferdinand Barth : Dante Alighieri - The Divine Comedy - Explanations. Darmstadt: Scientific Book Society, 2004.

- Ludwig Gottfried Blanc : Attempt at a purely philological explanation of several dark and controversial passages of the Divine Comedy. Publishing house of the bookstore of the orphanage, Halle 1861.

- Ludwig Gottfried Blanc: Vocabulario Dantesco. Leipzig 1852.

- Esther Ferrier: German transmissions of Dante Alighieri's Divina Commedia 1960-1983. de Gruyter, Berlin / New York 1994.

- Robert Hollander: Allegory in Dante's 'Commedia'. Princeton 1969.

- Robert Hollander: Studies in Dante, Ravenna 1980.

- Otfried Lieberknecht: Allegory and Philology. Reflections on the problem of the multiple sense of writing in Dante's 'Commedia'. Stuttgart 1999.

- Kurt Leonhard : Dante. From the series of Rowohlt's monographs. Rowohlt Taschenbuch Verlag GmbH, Hamburg 2001.

- Sophie Longuet: Couleurs, Foudre et lumière chez Dante. Paris 2009.

- Peter Kuon: lo mio maestro e 'l mio autore. The productive reception of the Divina Commedia in modern narrative literature. Frankfurt am Main 1993, ISBN 978-3-465-02598-6 .

- Enrico Malato: Studi su Dante. "Lecturae Dantis", chiose e altre note dantesce. Edited by Olga Silvana Casale et al., Roma 2006.

- Bortolo Martinelli: Dante. L'altro viaggio '. Pisa 2007.

- Giuseppe Mazzotta: Dante's Vision and the Circle of Knowledge. Princeton 1993.

- Franziska Meier: Dante's Divine Comedy: An Introduction , Munich: Beck 2018 (CH Beck Wissen; 2880), ISBN 978-3-406-71929-5 .

- Alison Morgan: Dante and the Medieval Other World. Cambridge 1990

- John A. Scott : Understanding Dante. Notre Dame 2004.

- Karlheinz Stierle : The great sea of meaning. Hermenautical explorations in Dante's 'Commedia'. Munich 2007.

- Karlheinz Stierle: Dante Alighieri. Poets in exile, poets of the world. Beck, Munich 2014, ISBN 978-3-406-66816-6 .

- John F. Took: 'L'etterno Piacer'. Aesthetic Ideas in Dante , Oxford 1984.

- See also the annual German Dante Yearbooks of the German Dante Society.

Research literature on individual aspects

- Henrik Engel: Dante's Inferno. On the history of hell measurement and the hell funnel motif. Deutscher Kunstverlag Munich / Berlin 2006.

- Henrik Engel, Eberhard König: Dante Alighieri, La Divina Commedia. The copy for Federico da Montefeltro from Urbino. Cod. Urb. 365 of the Bibliotheca Apostolica Vaticana. (Commentary on the facsimile). Anton Pfeiler jun., Simbach am Inn 2008.

- Francis Fergusson : Dante's Drama of the Mind: A Modern Reading of the Purgatorio. Princeton UP, 1953. Book on Demand: Princeton Legacy Library, 2015

- Robert Hollander: Dante, 'Theologus-Poeta'. In: Dante Studies. Volume 94, 1976, pp. 91-136.

- Andreas Kablitz: Art on the other side or God as a sculptor: The reliefs in Dante's Purgatorio (Purg. X – XII). In: Andreas Kablitz, Gerhard Neumann (ed.): Mimesis and simulation. Freiburg 1998, pp. 309-356.

- Andreas Kablitz: Videre - Invidere - The phenomenology of perception and the ontology of the purgatory (Dante "Divina Commedia", Purgatorio XVV). In: Deutsches Dante-Jahrbuch 74 (1999), pp. 137–188.

- Andreas Kablitz: Poetics of Redemption. Dante's Commedia as a transformation and re-establishment of medieval allegory. In: Commentaries. Edited by Glen W. Most, Göttingen 1999, pp. 353-379.

- Andreas Kablitz: Dante's poetic self-image (Convivio-Commedia). In: About the difficulties, (s) I to say: Horizons of literary subject constitution. Edited by Winfried Wehle , Frankfurt 2001, pp. 17-57.

- Andreas Kablitz: Bella menzogna. Medieval allegorical poetry and the structure of fiction (Dante, Convivio - Thomas Mann, Der Zauberberg - Aristotle, Poetics). In: Literary and religious communication in the Middle Ages and early modern times. DFG Symposium 2006, ed. v. Peter Strohschneider, Berlin 2009, pp. 222-271.

- Dieter Kremers: Islamic Influences on Dante's ‹Divine Comedy›. In: Wolfhart Heinrichs (ed.): Oriental Middle Ages . Aula-Verlag, Wiesbaden 1990, ISBN 3-89104-053-9 , pp. 202-215.

- Adrian La Salvia, Regina Landherr: Heaven and Hell. Dante's Divine Comedy in Modern Art. Exhibition catalog of the City Museum Erlangen, Erlangen 2004, ISBN 3-930035-06-5 .

- Klaus Ley [Ed.]: Dante Alighieri and his work in literature, music and art up to postmodernism. Tübigen: Franck 2010. (Main research on drama and theater. 43.)

- Marjorie O'Rourke Boyle: Closure in Paradise: Dante Outsings Aquinas . In: MLN 115.1. 2000, pp. 1-12.

- Rudolf Palgen : Dante and Avicenna. In: Anzeiger der Österreichischen Akademie der Wissenschaften, phil.-histor. Great. Volume 88 (12), 1951, pp. 159-172.

- Gerhard Regn: Double Authorship: Prophetic and Poetic Inspiration in Dante's Paradise. In: MLN 122.1. 2007, pp. 167–185 and the like: God as a poet: The reflection of fiction in Dante's Paradiso. In: Fiction and Fictionality in the Literatures of the Middle Ages. Edited by Ursula Peters, Rainer Warning. Munich 2009, pp. 365–385.

- Meinolf Schumacher : The visionary's journey into hell - an instruction to be compassionate? Reflections on Dante's 'Inferno' . In: Beyond. A Medieval and Medieval Imagination , ed. v. Christa Tuczay , Frankfurt a. M. 2016, pp. 79-86 ( digitized version ).

- Jörn Steigerwald: Beatrice's laughter and Adam's sign. Dante's justification of a literary 'anthropologia christiana' in the Divina Commedia (Paradiso I – XXVII). In: Comparatio. Journal for Comparative Literature 3/2 (2011), pp. 209–239.

- Karlheinz Stierle: Time and Work. Proust's “À la recherche du temps perdu” and Dante's “Commedia”. Hanser, Munich 2008, ISBN 978-3-446-23074-3 .

- Winfried Wehle : Return to Eden. About Dante's science of happiness in the "Commedia". In: German Dante Yearbook. 78/2003, pp. 13-66. PDF

- Winfried Wehle: Illusion and Illustration. The 'Divina Commedia' in the dialogue of the arts , in: Kilian, Sven Thorsten; Klauke, Lars; Wöbbeking, Cordula; Zangenfeind, Sabine (Ed.): Kaleidoskop Literatur. On the aesthetics of literary texts from Dante to the present . Berlin: Frank & Timme, 2018, pp. 53-85. PDF

- Winfried Wehle: The forest. About image and meaning in the 'Divina Commedia' , in: Deutsches Dante-Jahrbuch . Vol. 92 (2017). - pp. 9-49. PDF

Picture cycles for the Divina Commedia

- Sandro Botticelli: Sandro Botticelli. The picture cycle for Dante's Divine Comedy. Hatje Cantz Verlag, 2000. ISBN 978-3-7757-0921-7 .

- Gustave Doré: The Doré Illustrations for Dante's Divine Comedy. Dover Publications Inc., 1976. ISBN 978-0-486-23231-7 .

- William Blake: William Blake's illustrations to Dante's Divine Comedy , 1824

- William S. Lieberman: The Illustrations to Dante's Inferno. In: Robert Rauschenberg. Works 1950–1980. Berlin 1980, pp. 118-255.

- Pitt Koch (photographs): Dante's Italy. On the trail of the "Divine Comedy". Edited by Bettina Koch & Günther Fischer. Primus Verlag, 2013. ISBN 978-3-86312-046-7 .

- Johann Kluska : Extensive cycle of paintings on the "Divine Comedy". i.a. Galeria de Arte Minkner and private collections

Web links

- Project Gutenberg

- Dante Alighieri - Opera Omnia in German translations

- Translations by Bachenschwanz, Graul, Meinhard, Jagemann, Hasenclever

- The Divine Comedy translated by Karl Witte at Zeno.org .

- ELF project , original Italian text and two English translations (by Henry Wadsworth Longfellow and Henry Francis Cary)

- Bilingual digital edition of Dante's Hell , the original Italian text and a French translation by Guy de Pernon

- The Divine Comedy - Hell, Purgatory, Paradise as an audio book on LibriVox

- Summary of the content

- Illustrations of the Divina Commedia by Joseph Anton Koch

- Carl Vogel von Vogelstein: The main moments from Goethe's Faust , Dante's Divina Commedia and Virgil's Aeneis , 1861

- Lutz S. Malke, Sebastian Neumeister: Divine Comedy , in: RDK Labor (2015).

- Manuscript - Urb.lat.365 digitized from the Biblioteca Apostolica Vaticana

- DivineComedy.digital (Catalog of the Figurative Heritage of Divine Comedy)

Remarks

- ↑ J. Leuschner: Germany in the late Middle Ages . In: German history . tape 1 . Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, 1958, ISBN 3-525-36187-4 , Part Two , Section I, Subsection 4: “State Theories and Social Teachings”, p. 474 .

- ↑ The first guide, Virgil , with his more than 1200 year old epic Aeneid was the undisputed model for epics in Latin , while Virgil himself only had the two Homeric epics Iliad and Odyssey as models, which were written around 800 BC. Originated in an archaic Greek language.

- ↑ The first search for Arabic sources and parallels by the Spanish priest and Arabist Miguel Asín Palacios, 1871–1944, the results of which he found in his 1919 work La escatología musulmana en la Divina Comedia seguida de Historia y crítica de una polémica (1984 in 4 . Edition published in Madrid) has been scientifically inadequate. See Gotthard Strohmaier : Avicenna. Beck, Munich 1999, ISBN 3-406-41946-1 , p. 150.

- ↑ See also Gotthard Strohmaier: The alleged and the real sources of the "Divina Commedia". In: Gotthard Strohmaier: From Democritus to Dante. Preserving ancient heritage in Arab culture. Hildesheim / Zurich / New York 1996 (= Olms Studies. Volume 43), pp. 471-486.

- ^ Gotthard Strohmaier: Avicenna. 1999, p. 150 f.

- ↑ The dedication letter is available as full text on Wikisource: see An Can Grande Scaliger

- ^ Quote from Virgil; see D. Alighieri, H. Gmelin (transl.): The Divine Comedy. Stuttgart: Reclam Verlag, 2001; P. 9. Canto 1, verse 91/93.

- ^ Gotthard Strohmaier : Avicenna. Beck, Munich 1999, ISBN 3-406-41946-1 , p. 151.

- ↑ Inferno III 18.

- ↑ Cf. Manfred Fath (Ed.): Das Höllentor. Drawings and plastic. Munich, Prestel-Verlag 1991; P. 172.

- ↑ D. Alighieri, H. Gmelin (trans.): The Divine Comedy. Italian and German. Volume I, dtv classic 1988; P. 35. Canto 3, verses 1-9.

- ^ Gotthard Strohmaier : Avicenna. Beck, Munich 1999, ISBN 3-406-41946-1 , pp. 149-151.

- ↑ At this point Dante is very self-confident (unless it is a later addition): because he writes that these five great poets, Virgil, Homer, Horace, Ovid and Lukan, would have accepted him as the sixth.

- ↑ 2015 , Deutschlandfunk

- ^ Quote from Virgil; see D. Alighieri, H. Gmelin (transl.): The Divine Comedy. Stuttgart: Reclam Verlag, 2001; P. 65. Canto 17, verses 1-3.

- ↑ Canto 20, verses 58-72; see Aeneis 10, 199 ff.

- ↑ See for example the Vossler edition of 1942, with its economical but important marginal notes.

- ↑ Directory of the illustrated manuscripts from Bernhard Degenhart: The art-historical position of the Codex Altonensis. In: Dante Alighieri, Divina Commedia, Commentary on Codex Altonensis. Edited by the school authorities of the Free and Hanseatic City of Hamburg by Hans Haupt, Berlin: Gebrüder Mann Verlag, 1965, pp. 65–120.

- ↑ Facsimile by Luigi Rocca: Il Codice Trivulziano 1080 della Divina Commedia, 1337. Milan: Hoepli, 1921.

- ↑ Jérôme Baschet: Les justices de l'au-delà: les représentations de l'enfer en France et en Italie (XIIe - XVe siècle). Rome: École de France de Rome, 1993 (= Bibliothèque des Écoles Françaises d'Athènes et de Rome, 279), p. 317 f.

- ^ Fabio Massimo Bertolo, Teresa Nocita: L ' Officiolum ritrovato di Francesco da Barberino. In margine ad una allegoria figurata inedita della prima metà del Trecento. In: Filologia e Critica 31.1 (2006), pp. 106-117, pp. 110 f.

- ↑ Hein Altcappenberg (ed.): Sandro Botticelli - The Drawings for Dante's Divine Comedy. Catalog for the exhibitions in Berlin, Rome and London, 2000–2001, London: Royal Academy of Arts, 2000, ISBN 0-900946-85-7 .

- ^ Michael Brunner: The illustration of Dante's Divina Commedia in the time of the Dante debate (1570-1600). Munich: Deutscher Kunstverlag, 1999, p. 10 ff.

- ^ R. Steig (ed.): Achim von Arnim and Jacob and Wilhelm Grimm. Stuttgart, Berlin: Cotta, 1904; Pp. 69-71.

- ↑ Christian von Holst: Joseph Anton Koch - views of nature. State Gallery Stuttgart, 1989.

- ^ WS Lieberman, p. 119.

- ↑ Dante Alighieri: The Divine Comedy. 3 vols. German by Karl Vossler. With colored illustrations by Monika Beisner. 2nd Edition. Faber & Faber, Leipzig 2002, ISBN 3-932545-66-4 .

- ^ Dante Alighieri: Commedia. Edizione Privata. Illustrata da Monika Beisner. Stamperia Valdonega, Verona 2005.

- ^ Dante Alighieri: Comedy. Inferno, Purgatorio, Paradiso. Translated by Robert and Jean Hollander, illustrated by Monika Beisner. Edizioni Valdonega, Verona 2007.

- ↑ 2007 exhibition of the series of pictures. ( Memento from March 26, 2012 in the Internet Archive )

- ↑ Spanish-Italian: Galaxia Gutenberg, Barcelona 2003 ISBN 84-8109-418-8 (there are Spanish-Italian art volumes for all three parts of the G. K. von Barceló, bibliography in Art. Barceló); German-Italian synchronized edition only Das Purgatory . Without ISBN, RM Buch- und Medienvertrieb, Rheda 2005. In the translation by Wilhelm Hertz 1955.

- ↑ See Thomas L. Schumacher: Terragni's Danteum. Architecture, Poetics and Politics under Italian Fascism. 2nd, expanded edition, New York 2004.

- ^ Nine Circles of Hell.

- ↑ Interview by Alain Rodriguez (Vivante Records) . Nine circles. Archived from the original on October 18, 2013. Retrieved October 6, 2013.

- ↑ Lyrics The Divine Comedy on the Joint Venture archive website , accessed October 19, 2011.

- ↑ Excerpt, English

- ↑ Seymour Chwast: Dante's Divine Comedy, Hell, Purgatory, Paradise. Translated from the English by Reinhard Pietsch, Knesebeck Munich, 2011, ISBN 978-3-86873-339-6 .

- ↑ Michael Meier: The Inferno. Dante Alighieri, Michael Meier, Rotopolpress February 2012, ISBN 978-3-940304-35-3 .

- ↑ See the list on the website of the German Dante Society : Translations of the Divine Comedy.