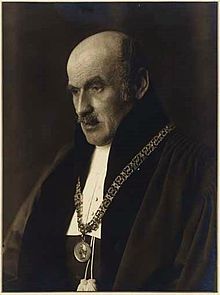

Karl Vossler

Karl Vossler (born September 6, 1872 in Hohenheim , † May 18, 1949 in Munich ) was a German literary historian, Dante researcher and one of the most important Romanists of the first half of the twentieth century.

Life

Karl Vossler was the son of Otto Friedrich Vossler , professor and director of the Agricultural Academy Hohenheim , and his wife Anna Maria, geb. Faber. He attended the humanistic grammar school in Ulm and then studied German and Romance languages in Tübingen, Geneva, Strasbourg, Rome and Heidelberg. In Tübingen he became a member of the Igel Academic Association in 1892 , to which he belonged until he left in 1931. In 1897 he was awarded a doctorate in German in Heidelberg for his work on the German version of the madrigal . In 1900 he was also granted the license to teach Romance Philology in Heidelberg and in 1902 he was appointed professor. His mentor in Heidelberg was Fritz Neumann . In 1909 he took over the chair for Romance studies at the University of Würzburg . In 1911 he accepted the call to the Ludwig Maximilians University in Munich, where he stayed until the end of his life. In 1926/27 and again in 1946 he was rector there.

Vossler married Countess Ester Gnoli in 1900, daughter of the Italian poet and literary historian Domenico Gnoli . Her younger son was the modern historian Otto Vossler , who - who grew up in their bilingual home - translated and edited his correspondence with the Italian anti-fascist Benedetto Croce after his father's death . The older son Walter is missing in World War II. In his second marriage from 1923, Karl Vossler was married to Emma Auguste Thiersch, the eldest daughter of the architect Friedrich von Thiersch .

During the First World War, Vossler served as an officer at the front. The accusations spread by Germany's opponents of the war prompted him to take patriotic statements in 1914. He supported both the Manifesto of the 93 and the declaration of the professors of the German Reich signed by 3,000 academics . The defeat and the Treaty of Versailles hit him hard, but he remained the European he was through education, friendships and marriage. In addition, there was his willingness to participate in the cultural development of Germany on the basis of the new state order. He made no secret of his rejection of National Socialism . In his speech to students on December 15, 1922, he drew the comparison between the swastika and the barbed wire. During his tenure as rector in 1926/27, the equality of the Jewish student associations and the order to hoist the black-red-gold Reich banner at university celebrations fell. In 1930, he complained publicly: "As we are the shame of anti-Semitism going on?" . In 1933 he campaigned for his Jewish colleague Richard Hönigswald to remain at Munich University.

Despite his republican-democratic sentiments, Karl Vossler was the type of apolitical scholar who saw in every ideology a threat to intellectual independence and a threat to culture. He even rejected the newly emerging artificial language of Esperanto because he saw in it equalization and flattening. In 1937 he was forced to retire due to his political unreliability - two years before the regular end of his career. He was also denied the right to continue teaching as an emeritus. He was allowed to keep his residence in the Maximilianeum . Vossler continued his scientific and journalistic activities privately. As his successor, the Tübingen professor Gerhard Rohlfs came to Munich in 1938 . Due to his reputation in the Romance world, Vossler was appointed head of the German Scientific Institute in Madrid in 1944. He did not take up office due to the war. At the new beginning of the university after the Second World War, Karl Vossler was involved as rector from March 1, 1946 to August 31, 1946. After his departure, on November 2, 1946, he gave the commemorative speech on the occasion of the unveiling of a plaque for the victims of National Socialism at the University of Munich, among them Kurt Huber and the students of the White Rose . He based his address on a Seneca quote: "This is how the true attitude of mind proves itself, which also does not submit to the judgment of others."

Vossler's students include Victor Klemperer , Eugen Lerch and Werner Krauss .

Scientific work

For many years, Italian poetry was the focus of his work. His arrangements and translations of Dante's Divine Comedy are still among the standard works today. Vossler later also worked on French literature and then made Spanish poetry the focus of his research. Even after his retirement, the importance of his work was recognized by numerous domestic and foreign honors. Vossler's scientific work contributed to detaching Romance studies from the narrowing perspective of positivism and returning it to the Humboldtian ideal of education with a new philosophical-aesthetic approach . His name is associated with the concept of idealistic new philology.

Honors

1912 Member of the Bavarian Academy of Sciences

1926 Pour le Mérite (peace class)

1927 Awarded the title Privy Councilor by the Bavarian State Government

1928 Honorary doctorate from the Dresden University of Technology

1937 Member of the Academies of Sciences in Vienna, Milan, Madrid and Buenos Aires

1944 Honorary doctorate from the University of Madrid

1944 Honorary doctorate from the University of Coimbra

1946 Member of the Accademia della Crusca

1944 Grand Cross of the Order Alfonso X el Sabio for Science and the Arts

1947 Awarded the Golden Medal of Honor of the City of Munich

1949 Honorary Doctorate from the University of Halle-Wittenberg

1949 Member of the German Academy of Sciences in Berlin (1946– 1972)

1949 Grave of honor in Munich

1949 Vosslerstrasse in Munich

1984 Foundation of the Karl Vossler Prize for Literature (awarded until 2002)

Fonts (selection)

- The German madrigal. History of its development until the middle of the XVIII. Century. Weimar 1898.

- Positivism and Idealism in Linguistics. 1904.

- The divine comedy. 4 parts, Carl Winter, Heidelberg 1907/1910. Second revised edition, 2 volumes, Carl Winter, Heidelberg 1925

- Contemporary Italian Literature from Romanticism to Futurism. Carl Winter, Heidelberg 1914.

- La Fontaine and its fabulous work. Carl Winter, Heidelberg 1919.

- Dante as a religious poet. Seldwyla, Bern 1921.

- Leopardi. Musarion, Munich 1923.

- Today's Italy. Munich 1923.

- Spirit and culture in the language. Carl Winter, Heidelberg 1925.

- Jean Racine. Hueber, Munich 1926.

- Politics and Spiritual Life. Munich 1927.

- France's culture and language. Carl Winter, Heidelberg 1929.

- Lope de Vega and its age. CH Beck, Munich 1932.

- Romanesque poet. Munich 1936.

- Introduction to Spanish poetry of the Golden Age. Conrad Behre, Hamburg 1939.

- Southern Romania. Oldenbourg, Munich 1940.

- The poetry of solitude in Spain. CH Beck, Munich 1940.

- From the Romance world. 4 volumes. Koehler & Amelang, Leipzig 1940/42.

- Inés de la Cruz, The world in dreams. (as editor), Leipzig 1941.

- The divine comedy. German by Karl Vossler. Atlantis Verlag, Zurich 1942

- Luis de León. Schnell & Steiner, Munich 1943.

- Research and education at the university. Munich 1946.

- Lope de Vega and his time. Biederstein, Munich 1947.

- Humboldt's idea of the university. Munich 1954.

literature

- Otto Vossler (Ed. & Transl.): Correspondence between Benedetto Croce and Karl Vossler . Suhrkamp, Berlin 1955.

- Hans Ulrich Gumbrecht : On the life and death of the great Romanists: Karl Vossler, Ernst Robert Curtius , Leo Spitzer , Erich Auerbach , Werner Krauss . Hanser, Munich 2002 ISBN 3-446-20140-8

- Frank-Rutger Hausmann : "Even in war the muses are not silent". The German Scientific Institutes in World War II . V&R , Göttingen 2001 ISBN 3-525-35357-X

- Utz Maas : Persecution and emigration of German-speaking linguists 1933–1945 . Vol. 1: Documentation. Biobibliographic data AZ. Stauffenburg, Tübingen 2010, pp. 840–848 online version 2018

- Kai Nonnenmacher: Karl Vossler et la littérature française. In: Wolfgang Asholt, Didier Alexandre Ed .: France - Allemagne, regards et objets croisés. La littérature allemande vue de la France. La littérature française vue de l'Allemagne. Narr, Tübingen 2011 ISBN 978-3-8233-6660-7 pp. 225-240

- Kai Nonnenmacher: Form and Life between Positivism and Idealism . In: Romance Studies , No. 1, 2015, pp. 171–190 Note

- Jürgen Storost: 300 years of Romance languages and literatures at the Berlin Academy of Sciences . Peter Lang, Frankfurt 2000, T. 1, pp. 484-491

Web links

- Literature by and about Karl Vossler in the catalog of the German National Library

- Works by and about Karl Vossler in the German Digital Library

- Newspaper article about Karl Vossler in the 20th century press kit of the ZBW - Leibniz Information Center for Economics .

- Publications about Karl Vossler in the Bavarian Bibliography

- Rector's speeches in the 19th and 20th centuries - online bibliography

- Entry on Karl Vossler in Kalliope

- Publications by Karl Vossler in Gateway Bayern

- Publications by Karl Vossler in RI-Opac

- Critical text of the translations of the Divine Comedy by Karl Vossler on Academia.edu

Individual evidence

- ↑ Hohenheim's directors, rectors and presidents ( memento from March 25, 2017 in the Internet Archive )

- ^ Letter from Benedetto Croce - Karl Vossler, Suhrkamp 1955

- ↑ in: The university as an educational establishment, 1923, pp. 13, 16

- ^ Contributions to the history of the Ludwig-Maximilians-Universität München, Vol. 3: Maximilian Schreiber, Walther Wüst, Dean and Rector of the University of Munich 1935–1945, page 155, Herbert Utz Verlag, Munich 2008, ISBN 978-3-8316-0676- 4th

- ^ "Bavarian voice against hatred of Jews" in defense papers. Messages from the Association for Defense against Anti-Semitism 40, 1930, p. 56

- ↑ Frank-Rutger Hausmann: “Even in war the muses are not silent”, p. 211

- ↑ Series of publications: Culture and Politics, ed. From the Bavarian State Ministry for Education and Culture, Issue 9, Richard Pflaum Verlag, Munich 1947.

- ↑ Lucius Annaeus Seneca: Letters to Lucilius , Letter 13: “Sic verus unbekannt animus et in alienum non venturus arbitrium probatur.” This quote can also be found on the plaque in the atrium of the university (places of remembrance in Munich ).

- ↑ Membership database of the academy

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Vossler, Karl |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | German Romanist |

| DATE OF BIRTH | September 6, 1872 |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | Hohenheim |

| DATE OF DEATH | May 18, 1949 |

| Place of death | Munich |