Persecution of sodomites

As a sodomite persecution that is criminal prosecution and execution called of men, which in the Middle Ages and the early modern period was accused of the "sodomite vice" ( vitium sodomiticum ) to have practiced.

term

Today, in German-speaking countries, sexual intercourse with animals ( zoophilia ) is called sodomy . In contrast, the Middle Ages included very different “unnatural” practices under this term, but mainly anal intercourse . Outside of the German language, the term is now used for anal intercourse, including non-homosexual ones.

The Sodomite vice has been referred to as the "silent sin", the "sin without a name" or "that terrible sin that cannot be named among Christians". The phrase "vice against nature" ( vitium contra naturam ) was used most frequently .

Since the concept of homosexuality only emerged in the 19th century, it is misleading to call the persecution of sodomites homosexual or even gay persecution. Nonetheless, “sodomite” was primarily understood to mean a man who practiced anal intercourse with another man .

The Middle Ages , however, cannot only be described as a story of repression with regard to today's concept of homosexuality , because at the same time love between men was considered nothing out of the ordinary and was rarely associated with the concept of sodomy. Same-sex pairs of friends were sometimes also blessed by the church as elective brothers and buried next to each other.

Etymologically , the word sodomy is derived from the biblical narratives in Genesis , chap. 18 ELB and 19 ELB from the city of Sodom , whose inhabitants fell into sin and were therefore buried by God under a rain of fire and brimstone .

Theological discourse

In the Old and New Testaments, the Sodom story was generally received as the epitome of human falling into sin and above all as a warning example of divine punishment. The story of the attempted attack by the sodomites on the angels who were guests at Lot ( Gen 19.1 ELB ) shows striking similarities with that of the Levite from Ephraim in the Book of Judges , chapter 19: Both stories deal with collective violence against foreign guests, and in both cases this violence is punished with the destruction of the city. Also in the book of wisdom (chapter 19) the motive of violence against foreign guests is mentioned with an explicit reference to Gen 19.

The association of the sins of the sodomites with fornication between men corresponds to a later understanding of this narrative and goes hand in hand with the interpretation in a sexual sense of the request of the sodomites to Lot: "... Bring them out to us, that we may know them" ( Gen. 19.5 ELB ). This meaning of the word "to know" is confirmed in the Bible and is used, among other things, in the genealogical records: " And Adam recognized his wife Eve, and she conceived and gave birth to Cain " ( Gen 4,1 ELB ), ( Gen 4, 25 ELB ). It cannot be guaranteed whether such an understanding was already based on some New Testament allusions to the Sodom motif ( Jud 7 ELB ).

The church fathers

Even the later patristic commentators initially failed to distinguish in their interpretation of the Sodom story between the sin of lust in general and “unnatural fornication” in particular. Even the older, non-sexual interpretations of history lasted for centuries. Jerome explained in accordance with ( Isa 3,9 ELB ) that princes are considered sodomites when they brag about their sins in another country. Ambrose , on the other hand, emphasizes the violation of the hospitality in the threat of the Sodomites to rape the three angels, but at the same time cites the malice, indolence and especially the lust of its inhabitants as reasons for the destruction of the city. For Gregorius, however, it is already clear that Sodom was punished for his "unlawful desires". "To flee from the burning Sodom is to reject the illicit fires of the flesh ". Of the four great Doctors of the Church , however, it is only Augustine who explicitly points out that Sodom was destroyed because fornication with men flourished there out of habit . The most detailed description of same-sex acts can be found in the Eastern Fathers of the Church, especially in the canons and canons of Johannes Nesteutes from the 6th century. There, however, only anal intercourse ( arsenokoitia ) is condemned as a perfect sin. It is noteworthy that anal intercourse between spouses was viewed as more reprehensible than anal intercourse between unmarried men. Mutual masturbation among men, women and between men and women were, however, viewed as equal and punished comparatively mildly. So the same-sex aspect was not seen as serious; on the contrary. It is therefore questionable to what extent the historical concept of sodomy and the modern concept of homosexuality can be equated at all.

Scholastic Definitions

Sodomy first appeared as a noun in a church pamphlet in 1049, where it owes its new creation to a rhetorical analogy : In his Liber Gomorrhianus , the Benedictine monk Petrus Damianus calls the then Pope Leo IX. to eradicate the sodomite vice from the church by removing those who are guilty of it of their spiritual dignity. In this context he coined the noun sodomia with the help of a polemical parallelism: "If blasphemy is the worst sin, I don't know in which way sodomy would be better."

Damian bases the term on a grouping of completely different sexual acts . The only thing they had in common was that they contributed nothing to procreation , the only legitimate purpose and ground of human sexuality for traditional Christianity . For Damian, four forms constitute the sodomite sin in ascending order: self-defilement ( masturbation ), mutual grasping and rubbing of the male genitals , ejaculation between the thighs and anal intercourse.

Thomas Aquinas followed a different logic of subdivision in the 13th century. According to him, the “sin against nature” is one of six types of lust with four subtypes, namely masturbation, intercourse with a “being of a different kind”, intercourse with a person who does not have the required sex, and the unnatural cohabitation, for example through the use of improper instruments or in other "monstrous and bestial ways". The fornication with an animal weighs the most heavily, the "uncleanness" which one commits with himself least of all.

Persecution practice

Late antiquity

In the middle of the 6th century, the Byzantine emperor Justinian I imposed a total ban on "unnatural fornication" in his amendments to the law, referring for the first time to Sodom and Gomorrah and warning of "earthquakes, famine and plague " as consequences of such activities. In an anonymously published pamphlet against the imperial couple, which left nothing to be desired in terms of clarity, the contemporary historian Prokopios of Caesarea shed light on the political background of this law. He suggests that Justinian and his wife and co-regent Theodora I used the law primarily as a means of getting personal enemies out of the way under a cheap pretext and deliberately plundering people who had great wealth. The punishment lacked any legal form, "because the punishment was carried out without a plaintiff, and the testimony of a single man or child [...] appeared to be fully valid evidence". On the basis of two cases, Prokop finally describes the popular resistance that the persecution of individuals for pederasty or alleged sexual intercourse with men ( gamoi andron ) provoked in the “entire people”.

However, there is no evidence that the Church ever endorsed, or even publicly endorsed, Justinian's law. Rather, she soon became a victim of the bloody hustle and bustle to which the imperial couple had empowered themselves with the help of the two novels. The only people punished by Justinian whose full names have been handed down to this day are both prominent bishops of the time: one, Isaiah of Rhodes , tortured and exiled with men for alleged fornication , the other, Alexander of Diospolis in Thrace , according to this castrated according to the provisions of the law and taken publicly through the streets.

Middle Ages and early modern times

Up until the 13th century, sodomy was not a criminal offense in the countries of Europe, but merely one of many sins in the church books of penance . However, that changed in the context of the crusade propaganda against Islam , which politicized the term sodomy. Mohammed , the "enemy of nature", popularized the sin of the Sodomites among his people, it was said in the contemporary pamphlets. The Saracens would rape bishops and abuse Christian boys for their carnal desires. Only a little later, sodomy was also one of the standard accusations against the heretics , so that heretic became a synonym for "sodomite" in Middle High German . The same thing happened in France with bougrerie and in England with buggery , both from the name of Bogomilensekte derived.

In the context of this agitation between 1250 and 1300, sodomy changed from a sinful, but mostly completely legal practice to an act that was punished with the death penalty almost everywhere in Europe . However, it was still primarily a means of denunciation and political intrigue, as in the case of the murder of King Edward II or the smashing of the Knights Templar . In addition, it was usually only punished if an act had seriously disrupted social peace, e.g. B. in the case of rape or the sodomitization of children. In reality, the courts dealt much more often with cases of extramarital sexual intercourse between a man and a woman than with same-sex acts between men, since the latter at least did not harbor the danger of illegitimate offspring.

However, there were temporally and regionally limited exceptions to this rule. An example of this is the city of Florence . After repeated plague epidemics had decimated the population from around 120,000 to around 40,000, the “Night Authority” was created there in 1432. She was solely devoted to fighting sodomy. The reasons for its introduction can only be speculated, but it stands to reason that it was part of a policy designed to curtail the sexual freedoms of young men in order to force them into marriage. She usually only punished anal intercourse with fines. But it was precisely because of this that she was able to set up a functioning system of total surveillance that worked with interrogations, rewarding informers, a network of spies and informants, and a leniency program. Up to the age of 30, every second male Florentine drew the authorities' suspicions at least once. At the same time, this persecution revealed the extremely high prevalence of sexual relationships among men and their relative openness. In Florence, “sodomy” did not take place hidden within the framework of a subculture , but was part of everyday social relationships. Only after 70 years was the authority of the night dissolved again. After the attempt to curb the "vice against nature" in this way, Florence gradually returned to the practice of persecution that was customary elsewhere: the threat of the death penalty as a matter of principle while largely tolerating simple acts of "sodomy".

Holy Roman Empire

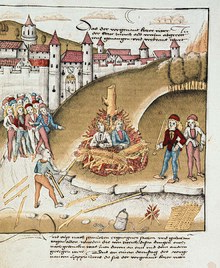

Probably the first execution for sodomy in the Holy Roman Empire is attested to in 1277 , when King Rudolf I of Habsburg condemned Dominus von Haspisperch to be burned at the stake . Around the same time, the Schwabenspiegel (approx. 1275/76) determined death by wheels for people who slander a man as a sodomite or a heretic, or who claim that he has committed fornication with animals . “Heretic” is here - synonymous with the term “sodomite” - to be understood as a term for a man who had sexual intercourse either with another man ( mandlaer ) or with an animal ( vichunrainer ).

In the centuries that followed, men were executed in many places “because of the heresy they had done together”, such as in Augsburg in 1381, in Zurich in 1431 or in Regensburg in 1456. The number of convictions can hardly be assessed in view of the generally poor, mostly only fragmentary tradition of old criminal cases. The canton of Zurich allows a concrete reference point , where the sources are good, because here the so-called "Richtbuch" books are completely preserved from 1375 with the exception of a single year (1739) ( Zurich State Archives , Section B VI). For a period of almost 400 years (from 1400 to 1798), these recorded a total of 1424 death sentences, of which 747 were based on property crimes, 193 on homicides and 179 after allegations of sodomy. In Zurich, “sodomy” was ranked third among the death-worthy crimes, far ahead of “witchcraft” (80 executions), which resulted in just half as many executions.

In 1532 Charles V created the Constitutio Criminalis Carolina (CCC), a uniform penal code for the empire, which remained valid until the end of the 18th century. Article 116 stated:

“Tight the vnkeusch, so against the coating of nature. Such a man with eynem vihe, man with man, woman with woman, drifting chaste, they have ruined life too, and one should judge them, the common wonhey with the less, from life to death. "

“Punishment for fornication if it happens against nature. Furthermore, if a man commits fornication with a cattle, man with man, woman with woman, they have also forfeited life, and according to the common habit they should be judged from life to death with fire. "

In contrast to London and Amsterdam , where there were wave-like persecutions of sodomites in the 18th century, the executions in the German Empire were limited to a few exceptional cases until the end. In Prussia, between 1700 and 1730, twelve people were executed under Article 116 of the CCC, nine of them for unnatural fornication with animals, but only three for sexual acts with men. The execution of the death sentence was carried out by beheading with the sword and then burning the corpses.

Late modern times and modern times

The persecution of sodomites continued in the late modern period in Europe as well as in the continents America and Australia discovered by Europeans in the 19th and 20th Century partly continued in a different form. The term sodomy was reduced to sex with animals in German usage. The suppression of homosexuality, however, continued to take place (see, for example, the further course of history under Section 175 of the German Criminal Code ).

literature

- John Boswell : Christianity, Social Tolerance, and Homosexuality: Gay People in Western Europe from the Beginning of the Christian Era to the Fourteenth Century . Chicago; London 1980.

- Alan Bray: Homosexuality in Renaissance England . New York 1982.

- Kent Gerard (Ed.); Gert Hekma (Ed.): The Pursuit of Sodomy: Male Homosexuality in Renaissance and Enlightenment Europe. London; Binghamton 1989.

- Jonathan Goldberg: Sodometries: Renaissance Texts, Modern Sexualities . Stanford 1992.

- Bernd-Ulrich Hergemöller : Sodom and Gomorrah: On everyday reality and persecution of homosexuals in the Middle Ages . 2nd, revised and expanded edition. New edition, Hamburg: Männerschwarm Verlag, 2000, ISBN 3-928983-81-4

- Mark D. Jordan: The Invention of Sodomy in Christian Theology . Chicago; London 1997.

- Hubertus Lutterbach : Sexuality in the Middle Ages. A cultural study based on books of penance from the 6th to 12th centuries . Cologne / Weimar / Vienna 1999.

- Helmut Puff: Sodomy in Reformation Germany and Switzerland, 1400–1600. Chicago; London 2003.

- Michael Rocke: Forbidden Friendships: Homosexuality and Male Culture in Renaissance Florence . New York; Oxford 1996.

- Erich Wettstein: The History of the Death Penalty in the Canton of Zurich . Winterthur 1958.

supporting documents

- ^ A b Georg Klauda: The expulsion from the Seraglio: Europe and the heteronormalization of the Islamic world. Männerschwarm Verlag, Munich, 2008, ISBN 3-86300-029-3 , pages 66ff.

- ↑ Spyros N. Troianos: Ταυτοπάθεια, reflective punishments and cutting off the nose. In: Rainer Maria Kiesow, Regina Ogorek, Spiros Simitis (eds.): Summa: Dieter Simon on his 70th birthday. Klostermann, Frankfurt 2005, ISBN 3-465-03433-3 , page 572.

- ↑ Edward Gibbon: Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire. Volume 5, Chapter 9, 1788, accessed on June 26, 2014 (translated by Cornelius Melville, reproduced on Projekt Gutenberg-DE ).

- ↑ Michael Brinkschröder: Sodom as a symptom: Same-sex sexuality in the Christian imaginary - an anamnesis from the history of religion. de Gruyter, Berlin / New York, 2006, ISBN 978-3-11-018527-0 .

- ^ Emperor Karl V .: Embarrassing neck court order (Constitutio Criminalis Carolina). (pdf, 679 kB) 1532, p. 33 , accessed on June 29, 2014 .