Literature as the nation's spiritual space

Literature as the intellectual space of the nation is the title of a speech that Hugo von Hofmannsthal gave on January 10, 1927 in the Auditorium Maximum of the University of Munich . The first printing took place in July 1927 in the Neue Rundschau in Berlin, the first book edition in the same year as a special publication by the Bremer Presse publishing house in Munich.

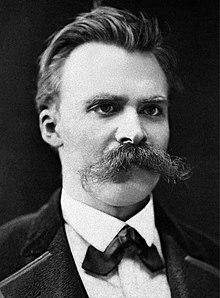

In the lecture he contrasted the literature and intellectual life of France with the “German disorder” in an exemplary manner. He conjured up the image of a nation on the way to the unity of literary intellectual forces. Based on Friedrich Nietzsche's criticism of time and culture , he determined the ideal of the “seeker” who parted from “prevailing thoughts of the time” in order to forge new bonds. Committed to a reflexively broken traditionalism and at the same time differentiating himself from Romanticism , Hofmannsthal no longer considered the holdings of tradition to be given and believed that he had to actively restore them in times of loss of validity.

The work is considered the culmination of German essay writing and, along with his drama The Tower, can be seen as the most important testimony to his last years. With its decisive tone and haunted argument, it is a manifesto , especially since Hofmannsthal summons his thought structure evocatively in the visionary reference to the historically powerful Conservative Revolution .

Research and criticism assign speech an important role in his work, although they also express skepticism and reservations about it and object that it has been misused for propaganda purposes.

content

Nation and literature

Hofmannsthal's speech begins with the definition of central elements: nation and literature.

Hofmannsthal understands the nation as a spiritual community that is linked by language as a cultural medium . The deep connection between the European nations cannot yet be seen in the comparatively young America . Language is not a mere means of communication, but a medium that, because of its tradition, is filled with the “spirit of the nations” and establishes the connection between the generations within the nation. Everything higher, culturally valuable has been passed on through scripture for centuries. Hofmannsthal does not limit this "literature" as "intellectual space" to the "barely manageable" jumble of books, but refers it to "all kinds of records". The word literature is more ambiguous in Germany and reflects the rift and difference between the educated and the uneducated. The luster of Goethe's spirit, which lay on this word a hundred years ago, has faded.

Model of French literature

As a counter-model, Hofmannsthal refers to the situation in France, which is closest to the German nation due to borders and fate. The French literature do not know the divisive education opposites, and the qualitative differences between large, medium and small plants would cancel already by the care with which even the fleeting time-bound strive for a pure, the thoughts of well-ordered reproducing speech.

In contrast to the torn German situation, the French literature does not endeavor to stand out effectively and up-to-date, but rather to “meet traditional demands.” The language norm holds the nation together and provides space for conflicting political tendencies. In "sociable" France, originality applies conditionally and in relation to others, while the German states it in and of itself . If loneliness is seen in German as “natural space for the mind”, in France it is only recognized in literary processing. The loneliness of literary figures - such as Molières - is like " Ovid's exile, but only the contradiction of sociability."

A key to Hofmannsthal's image of France is to be found in the term “believed wholeness”, by which he understands the unity of “natural and cultural life”, which is pleasantly different from “German disunity”.

“Where there is a believed wholeness of existence - not conflict - there is reality.” Through language, the nation becomes a “community of faith in which the whole of natural and cultural life is included.” Society and literature form a unity, there the whole Nation is held together by the "indissoluble fabric of the linguistic-spiritual." This is how language brings opposing political and social groups together under its unified umbrella.

Hofmannsthal now measures his own nation against this ideal of unity and representative existence in order to determine that its literary “intellectual powers” do not work together and that there is no question of the ideal of simultaneity and cultural tradition in it. The concept of “spiritual tradition” is hardly recognized. In Germany there is a conventional literature that is neither representative nor tradition-building.

The untimely seekers

Hofmannsthal does not stop at a blanket rejection of the literary situation in Germany: there are ghosts who have nothing to do with the usual literature, but still want to determine the intellectual life of the nation. These “outmoded spirits” thought little of the common social demands and looked for “the deepest, yes, cosmic bonds and the heaviest, yes religious responsibilities for the whole.” These “responsibility-laden and yet irresponsible”, who are “about the highest bonds “Strive, Hofmannsthal describes Nietzsche's word as a“ seeker ”. He summarized everything “high, heroic and also eternally problematic in German spirituality” and set it against the ideal of the self-satisfied German educational philistine.

His criticism of the German situation is clearly shaped by Nietzsche's out-of-time considerations . The German philistine of education wanted to transform the search and struggle comfortably into a being and having, in order to settle on it as an educational foundation, which he regards as an achievement of the classics as a permanent possession. In this philistine atmosphere, Nietzsche, like the “spiritual conscience of the nation”, overthrew pseudo-authorities and thrown off prevailing thoughts of the time in order to “keep our shadowy existence tied to the eternal”.

In the atmosphere of uncertainty, Hofmannsthal discovers occasional courageous carriers of a "productive anarchy", two of which he elaborates as an ideal type: the wandering, "intellectual emerging from the chaos", the "with the touch of genius on the high forehead" Lays claim to revolutionary leadership. For his warlike mission, he gathers companions and adepts around him who have to submit to him.

The other representative to be found in the chaos of the seeker was opposed to the ruler type and worked through the spiritual structure of the centuries with ascetic self-denial. If the latter wanted to overthrow in a revolutionary way, then he was sadly burdened with the scientific processing of a spiritual legacy that would become his “darkest fate” to preserve. If the “hubris of the will to rule” is in the “spiritual leader”, one of the “will to serve” can be recognized here.

While in the first model there are traits of Stefan Georges and Rudolf Pannwitz , to whom Hofmannsthal did not want to completely deny his respect, no matter how unsociable their nature was, one recognizes that Max Weber and Norbert von Hellingrath were the godfathers for the second .

The two ideal types, however, are only "shadows and shadows", since the real seekers move within these extremes and are legion, young and old scattered all over Germany in a wide variety of professions and each strive to "recognize the essence of things." Their secret cohesion "is the true and only possible German academy." In their "highest moments" they are seers, in which the "foreboding German nature" emerges again and who sensed the source of the people, "script readers, palm readers, star readers", “Sectarians of all sorts”, in which a lot - from Jakob Böhme to Johann Caspar Lavater - resonates and comes to life over the centuries.

In contrast to the romantic dreams of the 19th century , it is not about enthusiastic longing or dreamy piety for what has been, not about the "confusing mixture of web of concepts, about this cult of the mind above everything, this supremacy of the dream over the spirit" or the “voluptuous losing oneself in the natural” with which the romantics rushed over “all the blossoms of the East and West, to graze on their drunkenness-inducing sweetness.” Today's seekers would grimly resist the romantic temptations. They are blessed with a mistrust of the "irresponsible speculative" such as the "irresponsible musical". They were not looking for freedom, but bond. In this German struggle for freedom today it is about the wholeness in which soul , spirit and spirit stir.

It is true that the solitary service of the poet to draw the whole of the world into the depths of the ego in order to lift it up to a new reality is still the only existential content of the lonely "worldless German" since the French Revolution tore him from all ties and had given him the “limitless orgy of the worldless self.” But in the meantime lies the “terrible” nineteenth century. The spirit striving for new bonds has "walked a terrible path", has changed and stripped off the immature being forever. The sense of responsibility in science and the strict "scholarly methods" of having to confront everything with one another have left their mark. One could not rest "longer than a second" on any result, nor on the bed of a skeptical attitude - again and again new questions and decisions were posed "for life and death."

The conservative revolution

It is an experience when the searching spirit wrestles itself out of the “pandemonium” with the enlightenment that real life is only possible without a romantic escape from the world, in the “believed wholeness” and through “valid ties.” The dichotomy of life should be overcome and be converted into a spiritual unity.

The unifying process can be recognized as a long process that encompasses the beginning of the Age of Enlightenment until today. Hofmannsthal regards this as an “internal countermovement” against the upheavals of the 16th century consisting of the Renaissance and Reformation . It is about “a conservative revolution on a scale that European history does not know. Their goal is form, a new German reality in which the whole nation can participate. "

Emergence

Karl Vossler , to whom the speech was dedicated, had passed on to his friend Hofmannsthal an order from the poets' association The Argonauts and the Goethe Society for an event at the Ludwig Maximilians University in Munich. When drafting the speech, the demanding Hofmannsthal was soon plagued by doubts and believed that he was not up to the task. On December 19, 1926, he wrote to Willy Haas how much the lecture was time-consuming because of its high demands. You can't talk about something in particular because people are too impatient and in too great a need. But if you go into the fertile area of the general, it is difficult to delimit the dissolving topic. You quickly come to the most difficult things, encounter nominalism and realism and are forced to read Heinrich Rickert , Nietzsche and Edmund Husserl . But that would only be "the shell and not the core."

For the first edition of the conservative monthly European Revue , Hofmannsthal wrote an "leading article", which can be regarded as a prelude to the speech and whose concluding Stretta reminds of the last sentence of the speech, only that here it is about "creative restoration" and not from "Conservative revolution" was spoken of. It speaks of the great concept of Europe , without which the greatest minds would be unthinkable. As later in the lecture, it is about an era of restoration. "Behind the hustle and bustle of the doom prophets and bacchants of chaos, the chauvinists and cosmopolitans (...) I see the few individuals scattered across the nations who have agreed on a major concept: the concept of creative restoration." After Hofmannsthal told the editor, Karl Anton had met Prince Rohan with great suspicion at first and described him to Richard Strauss as an aristocratic, amateurish muddlehead whom he consistently wanted to avoid, he now, after careful consideration, stood up for him. Nevertheless, a little later he described him to Ernst Benedikt , the editor-in-chief of the Neue Freie Presse , as an "ambitious", "not entirely transparent individual."

background

development

After the beginning under the sign of Impressionism , Hofmannsthal's early poems showed an interest in social issues of the time. His works from around 1906 show the influence of Georg Simmel's philosophy of money and theories about the alienation of humans, which culminated in further disputes in the game of everyone (1911).

Hofmannsthal had dealt with the situation of language and literature several times. For example, in the famous letter of Lord Chandos from 1902, in the lecture The Poet and This Time and the late, short essay Wert und Ehre deutsche Sprache from 1927. With the language crisis described in the letter , which was experienced as existential , he put a topic in the The focal point that pervades his entire work and should also be echoed in the 1921 “ Schwierigen” in the figure of Hans Karl Bühl .

Hofmannsthal found the common assessment of his neo-romantic early work, which was repeatedly praised for the magical power of its exquisite verses, as a burden. This work is "as famous as it is not understood." With the draft of his Ad me ipsum and its delivery to Walther Brecht, he tried to counteract this interpretation. The research now assumes that the later work is predominant over the early work and sees Hofmannsthal's intellectual contour less from an aesthetic and theoretical decadence than from a political point of view.

With his successful collection “German Narrators”, with which its conservative effect began, he was not concerned with publishing another anthology , but rather - in the collection “the most beautiful of all German stories” - with a literary-political message: “Today's time is idolizing the insubstantial concept of the present”, although there is nothing “absolutely present” in the individual, development is everything and past periods of time live on in the next: “The present is broad, the past deep; the breadth confuses, the depth delights. ”So why should one always go in breadth?

The years of the world war deepened his concern for the development of Europe. The dissolution of the Danube Monarchy with its multiple upheavals prompted him to consider the Austrian multi-ethnic state as a model for a new, continental unity. For him, the war had devalued the legacy of the Enlightenment and opened the way to new types of state organization.

With the defeat in 1918, the cultural soil with which Hofmannsthal was spiritually and aesthetically rooted also broke away. A year before his death he wrote in a letter to Josef Redlich:

“Precisely because with the collapse of Austria I lost the soil in which I am rooted (...) because the in-one of the fate-bound political with the spiritual-cultural, the in-one of guilt and misfortune (...) my own experience is because my poetic existence has become questionable in this collapse (...) I can only remain silent about these things - if I do not want to ...

Hofmannsthal's ideal of unity is a linguistic and intellectual one founded by literature, not a territorial one. The demand for the spiritual concept of the nation is not the product of provincial or nationalist thinking. Hofmannsthal recognizes “the traits of an older and higher Germanness” in Austria and feels that the ideas of the Danube Monarchy are still alive; nevertheless, he did not question membership of the German nation.

Hofmannsthal himself characterized his attempt as a focus on the necessary. At a critical moment in history he wanted to interpret the restorative as well as anarchic endeavors from an independent attitude of the spirit.

Nietzsche's influence

Although Hofmannsthal has been looking for Nietzsche influences for a long time and these seem more foreseeable than tangible, it can be assumed that he was familiar with large parts of the work, read some books several times and was thus one of the few alongside Rainer Maria Rilke and George Belonged to "neo-romantics" who delved into the philosopher. As early as 1891 he wrote to Arthur Schnitzler about his joy in reading, “how my own thoughts crystallize beautifully in his cold clarity, the bright air of the Cordilleras.” A year later, he confided to Felix Salten that you experience more with Nietzsche than with “all adventures of our life."

In comparison with George and Rilke, Hofmannsthal also identified himself as a Nietzschean who no longer randomly threw up his philosophical image, but built it up systematically. Starting from the questions of the untimely reflections and the early tragedy writing, he turned to Zarathustra . He asked this work how it came about and came across the phenomenon of viewing thoughts as events beyond the control of the thinker himself. So they could only be stylized rhetorically in order to convince and to prove that the thinker believed in them.

According to Nietzsche's motto "to see science under the artist's optics, but art under that of life", Hofmannsthal - like Rilke and George - advocated overcoming the "turmoil" of modern life. For him this was characterized and confused by a number of antinomies due to the influence of science and technology . In this way he prepared to balance and overcome the multiple divisions on the basis of a spiritual art.

The Nietzsche admirer George, who was influential for the young Hofmannsthal, represented an art for art in his literary magazine Blätter für die Kunst that neither portrayed life naturalistically nor scientifically cemented it, but instead was supposed to replace the objective in a floating beautiful word image in order to achieve freedom win yourself. This freedom will not be able to deal with “world improvements and dreams of all happiness” or social revolutionary ideologies. In this sense Hofmannsthal, who blamed the fanatical ideologies and “sham poets” for the dissolution of the spiritual in art and ascribed the ugliness of modern culture to them, wanted to establish a new spiritual art. If for Nietzsche the fanatic was an “inward-looking warrior”, the new art was supposed to exclude this fanaticism. In his early essay, Poetry and Life , he formulated that what is really poetic is the "weightless fabric of words."

Other influences

Hofmannsthal's sociopolitical ideas have also been influenced by other contemporary authors. In some places in his work, the takeovers are so obvious that they take on the character of a blossom harvest. In Frederik van Eeden and Volker Gutkind's prophetic treatise Welt-Eroberung durch Heldenliebe from 1911 he found reasons for rejecting materialism. Combined with the wisdom of Asian religions, he saw this as an alternative to the technical European money economy. Rudolf Pannwitz, whose works also influenced him, promised a purified freedom and a new sense of reality. In the magical language of these role models, the crisis of the fin de siècle should be overcome in personal experience.

classification

Literary currents

As the conflicts and irreconcilable contradictions between the political left and right came to a head in the Weimar Republic , the most varied interpretations and battles were carried out on the intellectual field. Alfred Döblin and later Ernst Bloch (with his model of non-simultaneity ) discussed the conflict between modernity and tradition, between the intellectual currents that dominate the cities and the “older force” of the “rural”. According to this model, two cultures faced each other: a programmatically modern, avant-garde metropolitan culture and a retrograde, consciously anti-modern, thematically and stylistically backward-looking current that was interspersed with elements of the blood-and-soil ideology .

The crisis of meaning that Hofmannsthal also felt after the lost war and the Versailles Peace Treaty , which many perceived as a humiliating shame, reinforced a pessimistic cultural criticism . This had already developed in the late 19th century and turned against modernity, materialism and rationalism in various literary genres. In literary terms it was part of the counter-currents to naturalism and was found in the early works of Stefan Georges and Hugo von Hofmannsthal.

In contrast to the prevailing materialistic interpretation of the world, the different German currents, inspired by French symbolism , were alien and distant from reality. They did not want to reform the world politically, but rather to justify it aesthetically in the sense of Nietzsche's words (from the birth of tragedy ). The bohemian attitude towards the bourgeoisie was not based on the desire for economic reforms, but was primarily directed against their amusic-philistine sentiments.

At the end of the 19th century, poetry diverged in two different directions with a more socialist or aristocratic vision of the future. According to Fritz Martini, the “greatest emanation phenomenon in intellectual history”, as Gottfried Benn Nietzsche described it, worked in a characteristic way: “In naturalism, Nietzsche's effect and the annoyance corresponding to it led to the left, in symbolism to the right.”

Hofmannsthal's belief in the wholeness of life appears again and again as a motif in his poetry and prose , his dramas and essays. He opposed it to the multiple divisions into which "the spirit had polarized life." In this way, he hoped to restore the unity of the torn German spirituality in the course of a conservative revolution .

General political evaluations

France and Europe

For Friedrich Sieburg , France was just as role model and example as it was for Hofmannsthal. In his popular work God in France? from 1919 he dealt with the political and cultural differences between the nations and pointed - like Hofmannsthal - to the understanding of the French language. There is no more pure sign of the power of French civilization than the ability of every French person - “however untrained and neglected” to use his language. Language is "inextricably linked" with the concept of civilization, the social word is "just as little separated from poetry as poetry is from morality." French literature in all its richness would not turn away from public life, but be part of it.

In contrast to Germany, literature does not move on the fringes of society, and even if the writers fight each other in France, they have something that they are proud of without exception: literature as an institution, as a “national cause.” The German misery shows the lack of common ground that characterizes literary life, the writer's self-hatred and his inability to “live in literature.” If German literature were able to “restore the knowledge of models and respect for them”, that would be a lot achieved, because what unites is the spiritual radiation that German is sometimes capable of. Nobody “recognized this more clearly and said it more beautifully than Hofmannsthal.” This message was the core of his efforts, so that he, whose figure the twentieth, “stained century could atone” and in which the “imperishable, albeit hidden, brightness of the German can be found Age of Education “reflects that the Praeceptor Germaniae was, which is so urgently needed today.

conservatism

Hofmannsthal's conservatism has been discussed again and again. While he was seen by some as the spokesman for Austria and even Europe, others spoke of reactionary tendencies. Like many intellectuals, he welcomed the outbreak of World War I as an invigorating departure from paralysis and an opportunity to renew the monarchy . The propagandistic formulas of his “Appeal to the Upper Classes”, which appeared as an editorial in the Neue Freie Presse on September 8, 1914 , were later maliciously commented on by Karl Kraus , for example .

Hofmannsthal is committed to a reflexively broken traditionalism that has occasionally been apostrophized as a “revolution of the spirit” or “ethical-aesthetic revolution”. He no longer considered the content of the tradition to be given and believed that he had to actively restore it in times of loss of validity - Hofmannsthal spoke of "lack of housing" and "mental distress". The synthesis of spirit and politics idealized by him had to reflect on tradition as well as be open to new ideas.

The Rousseau 's concept of freedom should be purified by a sense of duty and a sense of community and the individual are protected from the excesses of mechanization, resembled an attitude that certain conservative ideas. So some toyed with the idea of building a Western empire under "Germanic" leadership. They wanted to return to an “organic” political order, which should replace the European thinking that had fallen to materialism with a new order of values. Hofmannsthal can be seen as the governor of a conservative outlook, who, above and beyond his literary work, is particularly important for his social and cultural work: in a crisis-ridden epoch, he saw himself as the keeper of the great tradition who wanted to take on this task for the nation. Drawing on the treasure of spiritual tradition, he wanted to convey binding values to the present and make the overall context of cultural education visible. Some of his work is sometimes understood as a representative expression of a movement which, compared to historicism or positivism , puts the rank of the super-individual in the foreground. The turn of the conservative revolution proclaimed in his speech is seen as the key concept of this movement.

Conservative Revolution

Hofmannsthal's speech is important in terms of the history of its effects due to the introduction of the term “conservative revolution” into political discourse. Arthur Moeller van den Bruck's 1923 book “The Third Reich” can be regarded as their program and as an important document of anti-democratic thought in the Weimar Republic . In it he announced his vision of a holistic national ideal. The conservatism meant a return to the ideas of the nation for him, while the word "revolution" was referring to the restoration of a new order under that same banner. In contrast to van den Bruck, who does not even use the term, Hofmannsthal's reflections lack the concrete realpolitical direction, aestheticize politics and are of a literary-philosophical nature. Nevertheless, he coined the term Conservative Revolution with his speech . The connection was made by Hermann Rauschning , a former National Socialist who popularized the term in his 1941 work The Conservative Revolution (German: The Conservative Revolution - Trial and Break with Hitler) . Rauschning did not rely directly on Hofmannsthal's speech, but was inspired by a specialist essay by the German-American Germanist Detlev W. Schumann (1900–1986) published in 1939.

For Hofmannsthal, the development of German culture is shaped by isolated, albeit at times large, individuals who seek their artistic confirmation more in “cosmic bonds” than in the social sphere. In this individualistic way, great works were created, which, however, rise up like solitary peaks and are not part of any intellectual-social structure. Every creative spirit is left to its own devices and only knows its own, lonely path of existence, which cannot lead to a closed cultural unity, the spiritual space of the nation , but to a form of productive anarchy that determines German intellectual life. The conservative revolution is supposed to represent a synthesis of national idiosyncrasies planned in the greatest style. What the Romansh peoples have always possessed - the totality of existence as an experience of reality - should also be achieved in Germany in order to overcome the conflict. This is a difficult undertaking, since the German individual, who is completely on his own, does not find any valid order and therefore has to design everything from himself. No external norm should tame the chaos, but rather individualism should be overcome by itself in order to realize the spiritual and cultural unity of the nation. The "titanic seeker" makes his way through to the highest community, the "lonely self" overcomes the "thousand gaps ... of folkhood that has not been bound for centuries" in order to complete the order that Hofmannsthal calls a true nation , an ideal state in where spirit and life are no longer separate.

In an extensive description and interpretation of the correspondence between Hofmannsthal and George, Theodor W. Adorno complained about Hofmannsthal's elitist attitude and the susceptibility of the “right-wing circles” sympathizing with him to National Socialism , to which the George School opposed more resistance. Hofmannsthal, trusting in the continuance of the Austrian tradition, made an ideology for the upper class and ascribed a false humanistic outlook to it. He also came up with a fictional aristocracy that "pretends to have fulfilled his longing."

In a longer letter, Walter Benjamin praised Adorno's contribution, but stated in defense of the criticized that the latter “stood by his gifts all his life as Christ would have confessed to his rule if he had to thank him for his negotiation with Satan.” The The poet's unusual changeability went hand in hand with the awareness that “betrayal was best in himself”. For this reason, no familiarity could " scare him with the light ".

According to Sue Ellen Wright, Hofmannsthal oriented himself in contrast to many other conservative theorists who advocated “real” German ways of life, on genuinely Austrian achievements, which he considered to be an inheritance from which all of Europe could draw. Hofmannsthal's late works then document his attempt to deal with traditionalist and revolutionary authorities. An interpretation of Salzburg's great world theater shows that Hofmannsthal rejects violence as a means of enforcing egalitarian demands. He had opted for a "further developed hierarchical world order" based on conservative-revolutionary figures of thought. The play of forces in the different versions of the tower reveals even more complex possibilities. Although it may seem ambiguous as a model for solving political dilemmas, it separates Hofmannsthal from those who would have sought a dictatorship for their own sake. In its final version, the piece even shows a keen skepticism towards the mystical heroes from the sphere of royalty, for whom Pannwitz and van Eeden had been the godfather.

Walter Jens explains Benjamin's notion of “betrayal” in a similar way to Thomas Mann in terms of apolitical aestheticism : the abandonment of the “necessity to assert oneself against reality” recognized in the Chandos letter ; to be a virtuoso like Gabriele D'Annunzio , someone to whom art means more than reality, Nietzsche more than the adventures of life. He held on to terms that had long been obsolete, although with his ingenious gifts he could have taken the path of a Kafka .

Effect and reception of the speech

Seven weeks after Hofmannsthal's lecture, the conservative humanist Rudolf Borchardt, a friend of his, gave a speech at the same university with the resounding title “Creative Restoration”.

In a letter to Max Brod in 1931, he described his views of conservatism and revolution in times of structural decline, which called the existence of the old world order and values into doubt. He wanted to defend the “tradition of the German spirit within the European” by all means: that of “conservatism against anarchy” and that of the “revolutions against the compromise with anarchy that has become static.” He did not speak of “bloody revolutions”; but there was consensus between him and Hofmannsthal that the "creeping (...) rape", which only appears to be non-violent, can only be broken by violence. In this context, Borchardt interprets Hofmannsthal's “conservative revolution”, which he later called “creative restoration” in the same place, as not political.

Thomas Mann , who in 1921 still used the term Conservative Revolution in a positive sense in connection with an evaluation of Nietzsche , but had publicly distanced himself from its ambitions in the year of the speech, referred to the tragedy during the time of National Socialism that of all things the aristocratic aesthetic Hofmannsthal, whom he held in high esteem as a poet and stylist, had become one of the spokesmen for a raw and barbaric movement.

As an apolitical spirit, Hofmannsthal paid little attention to the realization of the conservative revolution of which he unsuspectingly spoke. The gap typical for Germany between the spirit and its political realization has given it boldness and freedom, but also a lack of relationships and irresponsibility. The speech must now posthumously serve as “prophecy and confirmation of the atrocity” and contribute to its spiritual support. This is the same abuse that is practiced with Nietzsche, Wagner and George.

In a conversation he had warned Hofmannsthal “about the approaching one”, “whom he was promoting in a certain way.” However, Hofmannsthal passed it over “with some nervousness”. Today, 1936, the poet would probably face the reality of the movement with the same disgust as Thomas Mann had a few years earlier. Since Hofmannsthal saw the religious movement of the conservative revolution as directed against the Reformation and the Renaissance, he would have to regard the Reformation as a freedom movement. But that is wrong, since it was itself a “conservative revolution”. It is also questionable to view the seventeenth to twentieth centuries as a “conservative movement unit” against the freedom of the sixteenth. Hofmannsthal's approach is arbitrary and determined by his “love of the baroque”.

Because of his speech, Ernst Robert Curtius placed Hofmannsthal in the tradition of restoration thinkers such as Antoine de Rivarol , Edmund Burke and Karl Ludwig von Haller . Carl Jacob Burckhardt, a friend of Hofmannsthal, turned against it . He pointed out that with this interpretation the political position of Hofmannsthal from the fifth act of the tragedy The Tower , whose protracted creation Burckhardt had witnessed, would be cleared away and confiscated. Hofmannsthal's source for the term Conservative Revolution is the book The Middle Ages and Us by Paul Ludwig Landsberg. Landsberg, a student of Max Scheler , established a regularity in Western history that he viewed as a circular development. It runs from order through habit to anarchy, before finally returning to order. The present, perceived as disoriented, was to be renewed by the medieval idea of ordo, since the unstoppable staggering age needed a bond and not a solution. At the end of his writing he enthusiastically invoked the conservative revolution: “The conservative revolution, the revolution of the eternal, is what is becoming and already being of the present hour. Those standing in it are those with whom my title should summarize me as "we". "

For Ralf Konersmann , the speech in style and choice of words moves on a fluid border between restorative criticism of civilization and conservative revolution.

An undifferentiated identification with the goals of the Conservative Revolution can, according to Sue Ellen Wright, lead to misinterpretations, since this term refers to the most diverse varieties of political engagement from intellectual theorizing to activism.

Hofmannsthal wanted to announce positive intellectual developments with his speech and was not blind to the dangers associated with the Conservative Revolution. Although he supported their various programs and saw a place in Europe's future for their supporters, he did not look forward to it without reservations. With his personal expression of Austrian conservatism, he wanted to hold on to a peculiar status quo rather than a revolution that raised a past stylized into an ideal as a program.

For Hermann Rudolph, the speech testifies to an increasing unconditionality in Hofmannsthal's cultural-political thinking. If in his 1906 speech The Poet and This Time or in the speeches on Beethoven he tried to “restore and renew the nation in the individual ...”, he now detaches himself from concrete social contexts and shifts the crisis into personal problems of existence and proclaim a true nation bearing mythical features and underlining the moment of the absolute. By rejecting the emancipation of the individual, instead of speculative-utopian, even marginal-esoteric considerations, Hofmannsthal reveals reactionary tendencies. What used to appear as an artistic expression within a specific historical moment is transformed for Rudolph into a free-floating structural model. The author points out that, as Thomas Mann feared, the speech was occasionally interpreted and abused in the National Socialist sense: Heinz Kindermann , NSDAP member and National Socialist ideologue, drew a line of development in his book Des Deutschen Dichters Sendung im Gegenwart Arthur Moeller van den Bruck to Stefan George and Hofmannsthal to the “ seizure of power ”, in which he saw the ideas of the conservative revolution realized. Hildegard Rheinländer-Schmitt interpreted the development in her book Decadence and Overcoming it with Hugo von Hofmannsthal in a similar, if even more fatal, sense .

In his biography Hofmannsthal. The Austrian journalist Ulrich Weinzierl is ambivalent about the poet's political significance by describing both his naive misjudgments and the exaggerated accusations of his critics. The study " Origin and Ideology of the Salzburg Festival" by Michael P. Steinberg, which Weinzierl criticizes as partially flawed, has put Hofmannsthal again into ideological twilight and classified as "a kind of bridge builder" to fascism . For Weinzierl, this assignment is just as wrong and exaggerated as the suggested connection between the Great World Theater of the Salzburg Festival and the “political theater of the Nuremberg Reich Party Congress of 1934.” Nevertheless, he considers Hofmannsthal's patriotic statements about World War I, his Austrian journalism and assessment of Italy to be problematic and sees strange connections and personal continuities in them. He mentions the fundamental sympathies of the Austrian bourgeoisie for Italian fascism , which Hofmannsthal would not have left unimpressed, and points out that the poet was impressed by Italian emissaries at the third annual meeting of the Association for Cultural Cooperation in Vienna in 1926. Hofmannsthal praised the cultivated and “witty representatives” of the “glamorous nation” in an exuberant way. It is regrettable that such a differentiated intellectual as Hofmannsthal from the “Aryan Basic Community” could have swaggered or used the term “people” without reflection.

Manfred Riedel emphasizes Nietzsche's European perspective and his belief in the supranational appearance of Goethe, which comes to light in the speech. Nietzsche - being out of date - had repeatedly complained about the narrow-mindedness and the German national-provincial conceit of his time and referred to Goethe's exorbitant size, which would go beyond this framework. Drawing on this, Hofmannsthal designed his literary concept of an intellectual nation, which can be understood as a complement to Goethe's vision of world literature .

Goethe's work combines sociability with loneliness and testifies to the power of Germanness and his desire to achieve a synthesis of all traditional literatures, while Nietzsche would have been forced by loneliness to use the Goethean-influenced motto: "To be good German means to de-Germanize" with the latter Follow consistency and look for new bonds. In this sense, Hofmannsthal was troubled by the question of whether he should balance the tragic and outdated loner’s tendency to humiliate with pride and deny German or translate it into European.

His speech is that of the copier who understands literary tradition in order to interpret the fate of people and peoples. Hofmannsthal followed Nietzsche's ideas from Beyond Good and Evil , according to which French culture with its synthesis of north and south comes closer to Greek than to German, with "its gruesome Nordic gray in gray."

literature

Text output

- Hugo von Hofmannsthal: Collected works in ten individual volumes. Volume 10: Speeches and Articles III. (1925-1929). Fischer, Frankfurt am Main 1980, ISBN 3-596-22168-4 .

Secondary literature

- Anna Guillemin: The Conservative Revolution of Philologists and Poets: Repositioning Hugo von Hofmannsthal's Speech 'The Literature as the Spiritual Space of the Nation'. In: The Modern Language Review. 107/2 (April 2012), pp. 501-521.

- Peter Christoph Kern: On the ideas of the late Hofmannsthal. The idea of a creative restoration. Carl Winter University Press, Heidelberg 1969.

- Hermann Kunisch: Hugo von Hofmannsthal's political legacy. In: Hermann Kunisch: From the imperial immediacy of poetry. Berlin 1979, pp. 277-301.

- Ute Nicolaus: Sovereign and Martyr. Hugo von Hofmannsthal's late tragedy poem against the background of his political and aesthetic reflections. Königshausen & Neumann, Würzburg 2004, ISBN 3-8260-2789-2 .

- O. von Nostitz: On the interpretation of Hofmannsthal's Munich speech. In: For Rudolf Hirsch. Frankfurt 1975, pp. 261-278.

- Manfred Riedel: In a conversation with Nietzsche and Goethe. Weimar Classics and Classical Modernism, Part Four, Acknowledgment of Spirit. Hofmannsthal's dialogue with Goethe and Nietzsche and the idea of a “conservative revolution”. Mohr Siebeck, Tübingen 2009, pp. 185–246.

- Hermann Rudolph: cultural criticism and conservative revolution . On Hofmannsthal's cultural-political thinking and its problem-historical context, Tübingen 1970.

- Sue Ellen Wright: Towards the Conservative Revolution. Hofmannsthal-Blätter, Series II, Frankfurt, Hugo von Hofmannsthal-Gesellschaft, Frankfurt 1974.

Web links

- e-Text ( Zeno.org )

- Digitized version of the edition published by the Bremer Presse publishing house, Munich 1927 (Bielefeld University Library).

Individual evidence

- ^ Raimund Lorenzer in: Kindlers New Literature Lexicon. Volume 7, Hugo von Hofmannsthal, The literature as the spiritual space of the nation. Munich 1990, p. 1014.

- ^ Hermann Rudolph: cultural criticism and conservative revolution . On Hofmannsthal's cultural-political thinking and its problem-historical context, on the shape of Hofmannsthal's cultural-political thinking, Tübingen 1970, p. 211.

- ^ Hugo von Hofmannsthal: The literature as a spiritual space of the nation. Collected works in ten individual volumes, speeches and essays III. Fischer, Frankfurt 1980, p. 24.

- ^ Hugo von Hofmannsthal: The literature as a spiritual space of the nation. Collected works in ten individual volumes, speeches and essays III. Fischer, Frankfurt 1980, p. 25.

- ^ Hugo von Hofmannsthal: The literature as a spiritual space of the nation. Collected works in ten individual volumes, speeches and essays III. Fischer, Frankfurt 1980, p. 26.

- ^ Kindlers Neues Literatur Lexikon, Volume 7, Hugo von Hofmannsthal. Literature as the nation's spiritual space. Munich 1990, p. 1014.

- ^ Hugo von Hofmannsthal: The literature as a spiritual space of the nation. Collected works in ten individual volumes, speeches and essays III. Fischer, Frankfurt 1980, p. 27.

- ^ Hugo von Hofmannsthal: The literature as a spiritual space of the nation. Collected works in ten individual volumes, speeches and essays III. Fischer, Frankfurt 1980, p. 28.

- ^ Hugo von Hofmannsthal: The literature as a spiritual space of the nation. Collected works in ten individual volumes, speeches and essays III. Fischer, Frankfurt 1980, p. 230.

- ^ A b Hugo von Hofmannsthal: The literature as a spiritual space of the nation. Collected works in ten individual volumes, speeches and essays III. Fischer, Frankfurt 1980, p. 30.

- ^ Hugo von Hofmannsthal: The literature as a spiritual space of the nation. Collected works in ten individual volumes, speeches and essays III. Fischer, Frankfurt 1980, p. 32.

- ^ Kindler's New Literature Lexicon. Volume 7, Hugo von Hofmannsthal. Literature as the nation's spiritual space. Munich, 1990, p. 1014.

- ^ Hugo von Hofmannsthal: The literature as a spiritual space of the nation. Collected works in ten individual volumes, speeches and essays III. Fischer, Frankfurt 1980, p. 35.

- ^ Hugo von Hofmannsthal: The literature as a spiritual space of the nation. Collected works in ten individual volumes, speeches and essays III. Fischer, Frankfurt 1980, p. 36.

- ^ Hugo von Hofmannsthal: The literature as a spiritual space of the nation. Collected works in ten individual volumes, speeches and essays III. Fischer, Frankfurt 1980, p. 37.

- ^ Hugo von Hofmannsthal: The literature as a spiritual space of the nation. Collected works in ten individual volumes, speeches and essays III. Fischer, Frankfurt 1980, p. 41.

- ↑ Quoted from: Hugo von Hofmannsthal: The literature as a spiritual space of the nation. Collected works in ten individual volumes, speeches and essays III. Bibliography, Fischer, Frankfurt 1980, p. 632.

- ↑ Quoted from: Ulrich Weinzierl : Hofmannsthal, sketches for his picture , Wissenschaftliche Buchgesellschaft, Vienna 2005, pp. 97–98.

- ↑ Quoting from Hugo von Hofmannsthal: European Review, Collected Works in Ten Individual Volumes, Speeches and Essays III , Bibliography, Fischer, Frankfurt 1980, p. 635.

- ^ Hermann Rudolph, Cultural Criticism and Conservative Revolution . On Hofmannsthal's cultural-political thinking and its problem-historical context, On the genesis of Hofmannsthal's cultural-political thinking, Tübingen 1970, p. 3.

- ^ Hermann Rudolph, Cultural Criticism and Conservative Revolution . On Hofmannsthal's cultural-political thinking and its problem-historical context, On the genesis of Hofmannsthal's cultural-political thinking, Tübingen 1970, p. 4.

- ↑ Werner Volke, Hugo von Hofmannsthal , Rowohlt, Hamburg 1994, p. 139.

- ^ Hugo von Hofmannsthal: German narrators. Introduction, pp. 8–9, first volume, selected and introduced by Hugo von Hofmannsthal, Insel, Frankfurt 1988.

- ↑ Quoted from Werner Volke: Hugo von Hofmannsthal , Rowohlt, Hamburg 1994, p. 146.

- ^ Werner Volke: Hugo von Hofmannsthal , Rowohlt, Hamburg 1994, p. 145.

- ↑ Bruno Hillebrand, Nietzsche: how the poets saw him , Hofmannsthal - George - Rilke, Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, Göttingen, 2000, pp. 68–69.

- ↑ Quoted from Bruno Hillebrand: Nietzsche. How the poets saw him. Hofmannsthal - George - Rilke. Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, Göttingen 2000, p. 68.

- ^ Manfred Riedel: In dialogue with Nietzsche and Goethe . Weimar Classics and Classical Modernism, Part Four, Acknowledgment of Spirit. Hofmannsthal's dialogue with Goethe and Nietzsche and the idea of a “conservative revolution”, Mohr Siebeck, Tübingen 2009, p. 192.

- ↑ Quotation from Manfred Riedel: In dialogue with Nietzsche and Goethe . Weimar Classics and Classical Modernism, Part Four, Acknowledgment of Spirit. Hofmannsthal's dialogue with Goethe and Nietzsche and the idea of a “conservative revolution”, Mohr Siebeck, Tübingen 2009, p. 193.

- ↑ Hugo von Hofmannsthal: Poetry and Life , Collected Works in Ten Individual Volumes, Volume 8, Speeches and Essays I, Fischer, Frankfurt 1979, p. 15.

- ^ A b c Sue Ellen Wright: Towards the Conservative Revolution. Hofmannsthal-Blätter, Series II, Frankfurt, Hugo von Hofmannsthal-Gesellschaft, Frankfurt 1974, p. 205.

- ↑ Walther Killy: Literature Lexicon , Volume 14, Weimar Republic. P. 488.

- ^ A. Herbert, Elisabeth Frenzel : Dates of German poetry. Volume 2: From Realism to the Present, Countercurrents to Naturalism. DTV, Munich 1990, p. 483.

- ↑ Quoted from Herbert A. and Elisabeth Frenzel: Dates of German poetry. Volume 2: From Realism to the Present. Countercurrents to Naturalism, DTV, Munich 1990, p. 484.

- ↑ Friedrich Sieburg: God in France? Das Wort, Societäts-Verlag, Frankfurt am Main 1954, p. 207.

- ↑ Friedrich Sieburg: God in France? Literature as an institution, Societäts-Verlag, Frankfurt 1954, p. 213.

- ^ Friedrich Sieburg: Marching into barbarism. Die Lust am Untergang , Deutsche-Verlags-Anstalt, Stuttgart 1983, p. 328.

- ↑ Friedrich Sieburg, Marsch in die Barbarei, Die Lust am Untergang, A handful of people, Deutsche-Verlags-Anstalt, Stuttgart 1983, p. 329.

- ^ Friedrich Sieburg: On literature 1924-1956. The shine and horror of education , Deutsche-Verlags-Anstalt, Stuttgart 1981, p. 365.

- ^ Friedrich Sieburg, Marsch in die Barbarei, Die Lust am Untergang , A handful of people, Deutsche-Verlags-Anstalt, Stuttgart 1983, p. 330.

- ^ Hugo von Hofmannsthal: Collected works in ten individual volumes. Speeches and Essays II, Bibliography, Fischer, Frankfurt 1980, p. 526.

- ↑ Historical Dictionary of Philosophy: Revolution, Conservative. Volume 8, pp. 982-983.

- ^ Hermann Rudolph, Cultural Criticism and Conservative Revolution . On Hofmannsthal's cultural-political thinking and its problem-historical context, On the genesis of Hofmannsthal's cultural-political thinking, Tübingen 1970, p. 4.

- ^ Kindler's Neues Literatur Lexikon, Volume 7, Arthur Moeller van den Bruck , Das Third Reich, Munich, 1990, p. 805.

- ↑ Walther Killy, Literature Lexicon, Volume 14, Weimar Republic. Pp. 488-499.

- ↑ Hans Mommsen : The playful freedom. The Road from Weimar to Downfall, 1918 to 1933 , Propyläen, Berlin 1989, p. 310.

- ↑ Detlev W. Schumann: Thoughts on Hofmannsthal's concept of the 'conservative revolution'. In: Publications of the Modern Language Association of America. 54, No. 3 (1939), pp. 853-899.

- ^ Armin Mohler : The Conservative Revolution in Germany 1918–1932. A manual. Third edition expanded to include a supplementary volume. Scientific Book Society, Darmstadt 1989, p. 10.

- ↑ Peter Christoph Kern, On the thoughts of late Hofmannsthal , The idea of a creative restoration, Conservative Revolution, Carl Winter Universitätsverlag, Heidelberg 1969, pp. 94–95.

- ^ Theodor W. Adorno: George and Hofmannsthal, on the correspondence 1891–1906. Collected Writings Volume 10, p. 205.

- ↑ Theodor W. Adorno, George and Hofmannsthal, on the letter exchange 1891–1906, Collected Writings Volume 10, p. 204.

- ↑ Quoted from: Walter Jens, Von deutscher Rede , Hugo von Hofmannsthal, Piper, Munich 1983, p. 166.

- ^ Sue Ellen Wright, On the Way to the Conservative Revolution , Hofmannsthal-Blätter, Volume II, Hugo von Hofmannsthal-Gesellschaft, Frankfurt 1974, p. 205.

- ↑ Walter Jens, Von deutscher Rede , Hugo von Hofmannsthal, Piper, Munich 1983, pp. 166–167.

- ^ Rudolf Borchardt, Collected Works in Individual Volumes, Speeches, Klett-Cotta, Stuttgart 1998.

- ↑ Rudolf Borchardt, Briefe 1931–1935, Hanser, Munich 1996, p. 92.

- ↑ Thomas Mann, Collected Works in Thirteen Volumes, Volume 10, Russian Anthology , Fischer, Frankfurt 1974, p. 598.

- ↑ a b Thomas Mann, Collected Works in Thirteen Volumes, Volume 12, Leiden an Deutschland , Fischer, Frankfurt 1974, p. 716.

- ↑ Quoted from: Hermann Rudolph, Kulturkritik und conservative Revolution . On Hofmannsthal's cultural-political thinking and its problem-historical context, On the shape of Hofmannsthal's cultural-political thinking, Tübingen 1970, p. 212.

- ↑ Ute Nicolaus: Sovereign and Martyr. Hugo von Hofmannsthal's late tragedy poem against the background of his political and aesthetic reflections. 4. The term “conservative revolution” in the Munich speech, Königshausen & Neumann, Würzburg 2004, p. 75.

- ↑ Quoted from: Ute Nicolaus, Souverän und Märtyrer, Hugo von Hofmannsthal's late tragedy poem against the background of his political and aesthetic reflections, 4. The term “conservative revolution” in the Munich speech, Königshausen & Neumann, Würzburg 2004, p. 76.

- ↑ Historical Dictionary of Philosophy: Revolution, Conservative. Volume 8, p. 983.

- ^ Sue Ellen Wright, On the Way to the Conservative Revolution, Hofmannsthal-Blätter, Volume II, Frankfurt, Hugo von Hofmannsthal-Gesellschaft, Frankfurt 1974, p. 204.

- ^ Sue Ellen Wright: Towards the Conservative Revolution. Hofmannsthal-Blätter, Series II. Hugo von Hofmannsthal-Gesellschaft, Frankfurt 1974, p. 206.

- ↑ Hermann Rudolph, Cultural Criticism and Conservative Revolution , On Hofmannsthal's cultural-political thinking and its problem-historical context, The literature as a spiritual space of the nation, Tübingen 1970, p. 218.

- ^ Hermann Rudolph, Cultural Criticism and Conservative Revolution . On Hofmannsthal's cultural-political thinking and its problem-historical context, On the shape of Hofmannsthal's cultural-political thinking, Tübingen 1970, p. 212.

- ↑ Ulrich Weinzierl: Hofmannsthal, sketches for his picture. Scientific Book Society, Vienna 2005, p. 91.

- ↑ Manfred Riedel, In Dialogue with Nietzsche and Goethe , Weimar Classic and Classic Modern, Part Four, Rückschein des Geistes. Hofmannsthal's dialogue with Goethe and Nietzsche and the idea of a “conservative revolution”, Mohr Siebeck, Tübingen 2009, p. 227.

- ↑ Manfred Riedel, In Dialogue with Nietzsche and Goethe , Weimar Classic and Classic Modern, Part Four, Rückschein des Geistes. Hofmannsthal's dialogue with Goethe and Nietzsche and the idea of a “conservative revolution”, Mohr Siebeck, Tübingen 2009, p. 228.

- ↑ Manfred Riedel, In Dialogue with Nietzsche and Goethe , Weimar Classic and Classic Modern, Part Four, Rückschein des Geistes. Hofmannsthal's dialogue with Goethe and Nietzsche and the idea of a “conservative revolution”, Mohr Siebeck, Tübingen 2009, p. 230.