The seventh ring

The seventh ring is the title of a cyclical volume of poetry by Stefan George published in 1907 . In terms of the history of the work, it marks a further departure from the symbolism and aestheticism of the early work to poetry that aimed at extra-aesthetic - religious, life-reforming and time-critical - effects.

Compared to previous cycles - such as the Year of the Soul - George gave up the usual tripartite division and presented a multitude of different styles. The focus of the work is on the Maximin poems , in which George deified a student who died young and which can be regarded as the basis of the myth of the same name . Instead of appearing as a renewer of the German poetic language and turning against the faults of modernity with perfect verse , the poet now distinguished himself as a seer in order to sanctify life with Maximin and to regain its lost unity.

With his most extensive collection, the poet's previously esoteric readership expanded considerably. As the transition from aesthetic to ethical existence, it forms the lyrical foundation of the George Circle .

Like the previous volumes, the editions were designed by Melchior Lechter artistically and were printed in types that were derived from George's handwriting.

Content and meaning

structure

With the number seven, George not only referred to the year of publication 1907 or the seventh day of creation , but also used it as a principle of order to divide the volume into cycles . In addition to the three , which shaped the order in Georges' previous books and had a deeper meaning for him and the circle, this number also played an important role in George's work. For Karl Wolfskehl it was a pure or sacred number that was in a mysterious connection with time, especially with the lifetime of a person .

The collection consists of seven circles or rings : poems of time , shapes , tides , dream darkness , songs and panels that are grouped concentrically around the fourth cycle, Maximin . The number of poems in each group is a multiple of seven; especially the first and fourth are determined by numerical principles.

Poems of time

The poems of time in the first part juxtapose the present, the “straw of the world”, figures and testimonies from cultural history, with which he subjects them to a critical examination and evaluation. In this way, the beginning of the ring appears as a fortress from which George hurls incendiary speeches at his nation, which has become lax, and holds up to it ingenious loners who “turn away from the noisy world.” Thus he highlights personalities of intellectual history such as Dante and Goethe , Nietzsche and Leo XIII. on the lyrical pedestal and erected monuments to them in order to emerge as Praeceptor Germaniae . The painter Arnold Böcklin, for example, who withdrew from the “vain hustle”, the “bogey and fat shopkeeper”, the “dishonorable” graces and “the everyday cheeky jubilation” in order to “get out of the silver air and narrow tops, out of magical greenery flood ... and night gorge to shout the primordial showers ”and thus prevented“ the holy fire from going out in cold times. ”In Leo XIII's poem, it is the“ Schranzen who (today) boast of changeless expressions on the thrones ignoble clink "that George despises, so he emphasizes in the Goethe-Tag the empty adoration of genius by ignorant contemporaries and admirers," who want to touch to believe ... "and know nothing," of the rich dream and sang. " The poet-philosopher Nietzsche, who withdrew from the depraved present into the icy heights of the mind, is immortalized with verses that end with the much-quoted words: "This new soul should have been singing, not speaking."

In the Dead City , George once again symbolizes the contrast between different times and denounces the present without culture or history. While the people below indulge in the restless hustle and bustle and ... haggle greedily in the endless streets , the mother city lies on top of the rock, forgotten by time, surrounded by black walls. She dreams and sees how her tower rises into eternal suns , the few inhabitants linger in the moment and indulge in contemplation under the protection of the consecrated images. At some point the teeming people below recognize their senseless abundance and want to go upstairs to escape their desolate pain and to recover in the pure air of the heights. But they are rejected because their number is a sacrilege.

Shape

With its extraordinary images, the second circle is one of the most haunting, even most radical parts of the work. He describes the cosmic upheavals and struggles that precede the birth of the god Maximin . George conjures up dark forces from the depths of the past, which he wants to overcome in order to make way for a new, lighter order, a process in which the influence of Gnostic teachings can be recognized. This inner tension is also reflected in the dialogic form of dialogues occurring in pairs in the four poems Der Fuehrer , Der Fürst and der Minner , Manuel and Menes and Algabal and Der Lyder . The cycle is dominated by polarities that alternate with one another. The juxtaposition of opposing poems is a basic feature of the work that can already be found in the Algabal .

The first poem, Der Kampf , depicts the defeat of a primeval giant against the light-fighting "beautiful curly god". The monster, "drunk with sun and blood", storms threateningly out of his cave, because he feels mocked by the dancing figure of light. But while he was victorious below, in the darkness of the “smoking embers”, this child up here, in the “fragrant hallway”, is fighting with light and knocks him down with a flash of lightning. With these verses the poet shapes his confrontation with the cosmopolitan , the transition from their dark realm to that of the "light god Maximin".

One of the best-known and most momentous poems by the figures is that of the Anti-Christian , a work of art consisting of nine terzets , which conjures up the image of a false prophet in the measured step of the dactyl . George uses images from the Old and New Testaments - the prophet descending from the mountain, the turning of water into wine, the warning of the Lord of the Flies , the fanfare of the Last Judgment - and processes them into a vision of the downfall of the coming Antichrist . While at the beginning the naive people marveled at the demagogue, in the further course the perspective changes, in that the scorn of the seducer himself is shown - ... "and you don't notice him", then from the authorial point of view of the poet the realization that the " Fürst des Geziefers “spreads his kingdom until finally the warning trumpet sounds.

tide

The first poems of the tides , still committed to Art Nouveau and published in the Blätter für die Kunst , reflect George's love for Friedrich Gundolf , who visited him in Bingen on August 4, 1899 and who was to become one of the most important people in his life.

It begins with the flaring up feelings for the young man - "when my wishes swarm around you ... my suffering breath swims around you ..." goes to the auspicious spring and a night of love with "glowing firmamente (s)" of the "Lush summer (s)" and ends with the admission in the mirror of the pond that "surrendered" to "wildly blazing". Feelings of goodbye and the desire to distance yourself are also expressed, the "inner call to you becomes quieter."

Maximin

The Maximin poems form the central fourth group and are entwined with the (also homoerotic) revered Maximilian Kronberger , a Munich student whom George had met two years earlier and who died on April 15, 1904 at the age of only sixteen. In these verses he idealizes the venerated as the “bringer of our salvation”, indeed elevates him to God (“... I see God in you”). The young man raised in this way, whose poetry George in the same year under the title Maximin. A memorial book published in 200 copies and provided with a preface appears as an incarnation of the will to form. In addition to the solemn deification, the basic trait of mourning is unmistakable:

The air is dull · the days are deserted.

How do I find honors that I show you?

When do I light your light through our days?

I only feel like

burying the splendor and the ruins of my days in the same way ·

With every way only my mourning way ·

Dragging along without doing and song the days.

Only

take this way out of the haze and gloom: accept the sacrifice of my dead days!

In addition to mourning poems, there are prayers of thanks , praise and proclamations : “Now lift it up! because it happened to you safely ... Praise your time in which a god lived! "

As Friedrich Sieburg wrote, the death of his beloved friend became a rapture for the poet , and with his urge to perpetuate he was able to put the no longer earthly at the center of his ring and - in poetic form - bring him back into new spiritual life. The group consequently closes with the rapture , the famous “I feel air from another planet”, verses that were set to music by Arnold Schönberg , among others .

Dream dark

In the fifth part, whose title stands out from that of the other headings with its disorderly character, poems are gathered that show George's night page, the transition from the “world of figures” of the day to the dream realm, as in the entrance and the landscapes , the night or the enchanted garden . A dark realm full of faces, visions and magic. Something of the exquisite of the earlier aestheticistic spheres shimmers once again by placing the words “gold” and “carnelian” next to each other right at the entrance to the invocation of a forest “Open up forest ...” and then rushing out with “dream wing! Dream harp sound! ”Ends. The first landscape is also full of exquisite twists:

The year’s wild glory runs through

the gloomy sense that was lost at noon

In a forest where the late flor of

saffron drips rust and purple.

Songs

The penultimate ring contains 28 songs of different characters. The first in particular are distinguished by their concise brevity, often with only two or three-letter lines of verse in iambic time. George had written and published many of them during an extremely productive period from 1892 to 1895. In addition to love songs, there are natural poetry , landscapes of southern beaches, bays and parks, to which the lyrical self often attaches melancholy memories and celebrates its loneliness.

The seven songs at the beginning are, despite the apparent lightness of their rhythm, rich and heavy structures that lack the Art Nouveau feel. The condensed, classic outline and the magic of these "movingly simple" pieces are expressed in the lines Im windes-weben :

In the wind-weaving

was my question

only dreaming.

Just smile was

what you were given.

A shine kindled

out of a wet night

-

Now the may pushes

Now I have to live

around your eyes and hair

All days

in sinews.

Panel

The last and most extensive circle of the panels comprises 70 short poems that are tied to specific places or people. Most of them are epigrams on friends or influential personalities like Gundolf or Derleth. The dance begins with lines for Melchior Lechter , the painter and book artist valued by George, and ends with the 25th poem, a quatrain on a poet . The concise local poems span an arc from the Rhine , with six verses the longest work of the section, over the Vosges and the Bavarian Forest, over Bozen, Munich and Hildesheim to Berlin. They show a panorama of cultural landscapes illuminated like a flash, which is provided with some critical views of Prussia and the capital with its "dead (em) turmoil and tinkling".

Emergence

Because of its compilatory nature and the long time it took to write, the Seventh Ring is not only the most detailed, but also the most heterogeneous volume of poems by George. It not only gathers the poems that were composed in these turbulent times for George, but goes back even further. It was very difficult for George to arrange the poems into a cycle with the Maximin center from the abundance of material . The seemingly artistic arbitrariness of different styles, which is difficult to concentrate, meant that George himself would later speak of the chaos of the seventh ring . ( → see interpretation )

In the design of certain, idealized ruler figures of the ring , a continuity of the personal and imperial cult can be traced back to the early work. While George had sung central leaders in the ancient priestly emperor Algabal , then in the oriental ruler of the hanging gardens and made them the focus of poetic and cultic veneration, this continues with Carl August in the contemporary poems.

With his new volume, George changed direction in that he dealt more intensively with his time and his own living conditions, so that biographical data of the people sung about in each case contribute to understanding. The George Circle gradually developed into a community in which artistic achievement seemed less important than supposedly higher forms of human existence. It is less the form than the metaphysical content that should determine the value of the poetry. George's sixth volume of poems, The Carpet of Life and the Songs of Dream and Death with a Prelude , had already turned away from the art-autonomous aestheticism of the early work and turned to art-religious with his introduction, in which the poet is consecrated by an angel of the “beautiful life” and life reform ideas.

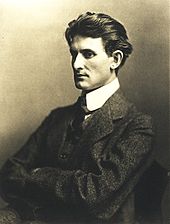

Ida Coblenz

The oldest are probably some of the songs that were written in the mid-1890s and are related to George's friendship with Ida Coblenz , who later became Richard Dehmel's wife , but which apparently did not fit into the rather strict conception of the volumes of poetry that have been published since then. Many of the poems had previously appeared in the Blätter für die Kunst , George's magazine.

From the summer of 1892 until the fall of 1896, George Ida had been quietly courting Coblenz. More than fifty poems and several pieces of prose addressed to the dear friend are due to this emotional state. The chants of a traveling minstrel , the middle section of the book of the hanging gardens , After the reading , Waller in the snow from the year of the soul, are related to a woman who knew how to evade his advertising, but she suspected that this man was , "Before whose ever cold hands" her "faintly dread", never "[would] be able to warm the blood of a woman."

Years after George's death, she confided in her diary what instinctively saved her from getting involved in something that could have been fatal for both of them. George's body was so alien to her, "as if he belonged to a different zoological field than I did." Some of the songs from the seventh ring can also be understood as processing the grief over a hopeless relationship.

Friedrich Gundolf

The relationship with Friedrich Gundolf shaped George like no other in his life. While on Gundolf's side it was primarily admiration for George and his work, feelings of love played a decisive role in George. Since he suspected that Gundolf had no homosexual tendencies, he did not want to push him back through impetuous behavior. So he wrote to him that he was “as much in awe of your beginning life as you were of my half-filled life” and otherwise proceeded cautiously, as he feared that he would otherwise be pushed back.

At the end of March 1900 they went to Northern Italy for a week, the first of many trips together. What happened between them during the days can at best be taken from the first poems of the tides , in which the relationship was poetically designed:

And an hour came: the knitted ones rested,

still glowing from the lip with a wild swing ·

There was a twilight in the room through which the gentle stars looked

From gold and roses.

George sensed the nearness of a possible happiness, but could not fully engage in the relationship, kept open options for retreat and confused Gundolf with different messages and sudden distance. In the spring of 1905 he met Robert Boehringer , then twenty years old , and fell in love with Ernst Morwitz, who was only 18 years old, a year later . Although other men also took on the role of favorites in the years to come, Gundolf retained the special role of his first lover, Georges.

Gundolf, in his glorifying George book, interpreted the poems that also go back to him more than twenty years later: The tides are for him George's book of love . Although his entire poetry was glowing with love, it was only here that he gave it “its own voice”, which otherwise speaks “through the mouth of the powers, the spirit or God, as a song of nature or fate”, but now personally as “ the naked passion of longing, striving, possessing and free movement of the heart ”is expressed. The futile dialogue between you and me from the year of the soul repeats itself, a work in which George still affirmed the melancholy loneliness of the self as a necessary law. While there love bears traits of nature or doom, in the tides it is freed from all "nature bondage". The lover could not believe in salvation in the year of the soul , which he succeeded in the tides, although he - in the form of Maximin - did not yet achieve it.

background

Three tendencies determine the cycle from the poems to the tables : the struggle of the upper against the lower powers or of light against the darkness, a German turn that is also connected with the turning away from (French) aestheticism, and finally the educational claim to leadership from art to all areas of social life. The three poems Templer , The Guardians of the Courtyard and The Anti-Christ are the starting points for what George would later call his state . Between 1907 and 1914 he converted this state into a closed system of values. These poems also give indications of the “educational program” that should be presented in the Stern des Bundes in a much more closed, stylistically more uniform form.

Art and life

The separation of art and life, which George spoke of in the preface to the Year of the Soul and thus assumed a position similar to that of Hofmannsthal in his essay Poetry and Life , now no longer seems possible with the seventh ring . If he had considered it “unwise” to turn to “the human and landscape archetype” for an understanding, since “you and I are the same soul”, this difference between author and lyrical self is now gradually disappearing. The poet-prophet had received divine things that had to be proclaimed to an illustrious circle.

This new task was associated with a decisive loss, the death of Maximilian Kronberger, whom George transformed into the supernatural, mythical figure of Maximin . Since his divinity was now rooted in the poet's personal experience of God, in his Damascus experience , and the proclaiming I was not an imagined one ("I see God in you"), George himself could be upgraded to a charismatic seer in dark times for his followers Ruler of secret Germany in the New Kingdom of a regained wholeness. The artist's truth was no longer an aesthetic game. No one in the George Circle doubted the personal nature of the seventh ring .

Cosmician

For George, the time after the turn of the century was a period of upheaval. His involvement in the circle of Munich cosmists around Alfred Schuler , Ludwig Klages and Karl Wolfskehl reached its climax in 1902/1903 and its abrupt end in 1903/1904 when Schulers and Klages' vehement anti-Semitism as well as ideological and personal differences to Schwabing's "Kosmiker- Crisis ”and thus led to the breakup of this circle.

George's closeness to this circle also illuminates his work. The primordial shudder conjured up in the Böcklin verses thus gains a new meaning when the spiritual background of the cosmists is considered. For Schuler and Klages, the shudder referred to the sudden awareness of an esoteric “holistic experience”, a connection with space. Regarding the development of civilization as a revelation from the original “cosmic integration”, Schuler and Klages believed in certain cultural moments or in individual people that they were particularly receptive to the “shivers of space” and the beginning and hoped for a renewal of archaic life the postmodern. Schuler spoke of new cosmic light showers , while Klages believed he recognized showers of life in Romanticism , with which one could be touched again by the power of the elemental even in sober everyday life. For George, the perception of elementary natural forces was an essential impulse, but he also saw in it, as indicated in the verses, a danger to the artistic intention: the shudder needs poetic containment, the pain of moderation, the Apollonian taming, is thus prevented It was possible that “in cold times the holy fire will go out.” For this reason, Gundolf declared that the “bloody shiver” in the “loud flame” of George's poetry was banished. This difference between George and the cosmicists illuminates the Maximin myth as well as the disintegration of the circle.

In Schuler's anti-Semitic-esoteric world of ideas, “cosmic energies” of man streamed together in the blood , a precious possession that was the “source of all creative powers”. This treasure is permeated by a special luminescent substance that tells of the cosmic power of the wearer, but can only be found in the blood of selected people. General rebirth in the Sun Children or Sun Boys was expected from them in times of decline . Now, according to Klages, there was a powerful enemy of the blood, the spirit, and the cosmic efforts should boil down to freeing the soul from the "bondage" of this spirit, that force which with progress and reason, capitalism, civilization - and equated with Judaism and would mean the victory of Yahweh over life. Schuler's tirades against “Molochism”, as he called his allusion to the child- devouring Moloch , hardly differed from the anti-Semitic phrases that were being used in Vienna around this time . Klages went beyond this by speaking of the pseudo-life of a larva that Yahweh used "to destroy humanity by means of deception."

Although George rejected many of Schuler's ideas as nonsensical, he was fascinated by him and recalled his conjured visions in several verses. Now Klages, who had grown ever closer to Schuler, wanted to drive a wedge between George and the Jewish member of the Karl Wolfskehl district . In 1940 he conformed to the spirit of the times and indirectly confirmed George's rejection of anti-Semitism: Klages claimed that in 1904 he had seen through at the last moment that the George Circle was "controlled by a Jewish center". He had given George the choice by asking him what "binds" him to "Judah" ... ". George avoided this conversation. Wolfskehl, who characterized himself as "Roman, Jewish, German at the same time" and can be seen as an important representative of the Jewish reception of George, initially believed in a symbiosis of Germanness and Judaism and was guided by the works of the poet, who was written in the star of the Bund in the sense of an elective affinity called Jews as the "misunderstood brothers", "from glowing desert ... home of the ghost of God ... immediately removed."

However, the poet was less concerned with his relationship with Judaism than with art. Ultimately, Maximin can be seen as George's answer to the savior expected by Schuler, the sun boy , but in a sense that contradicts the cosmists' obscure worldview: if Maximin was the unity of “cosmic shiver” and Hellenic amazement, this worked for Klages and Schuler is aiming at the feared victory of the spirit, of light over pleasant darkness.

For George, Maximin , with whom he broke away from the cosmicists, was supposed to reconcile the Apollonian and Dionysian principles that Nietzsche had already distinguished in his early work . So he was "one at the same time and different, intoxication and brightness."

So he escaped from a mental crisis that he was experiencing at the time: He founded the “Maximin myth”. Where he previously “feared when looking into [his] next future”, he now gained personal support such as religious legitimation from the deification of Maximilian Kronberger, known as Maximin, whom he praised as “master of the change”. Last but not least, this divinization provided himself, who was the only one who believed he had recognized the divinity of Maximine, the legitimacy to function as an absolute and undisputed “master” in the now constituting George circle . At the same time, the homosexual poet got to know younger men such as Friedrich Gundolf (since 1899, see An Gundolf ), Ernst Morwitz and Robert Boehringer (around 1905, see An Ernst and An Robert ), who admired him unreservedly and with whom they formed close friendships and love relationships developed.

Maximin myth

In the Maximin myth, elements of the Greek and Christian motif of the divine child , which can already be found in the Egyptian Horus myth, are repeated . Before Nietzsche's historical horizon, George believed he would deliver for his circle what the Mallarmé circle had promised and Zarathustra had promised: to create a world before which one could kneel as "last hope and drunkenness."

religion

In this transfigured sense of drunken adoration, George spoke of him in his preface to Maximin as the savior and “actor of an almighty youth” who closed himself off to the circle in difficult times when some ventured into “dark districts” or “full of sorrow or hatred” , returned the trust and fulfilled it with the "bright new promises." "This truly divine" has changed and relativized everything by "the servile present lost its sole right" and calm returned, which let everyone find his center. Outsiders would not understand that the circle had received such a revelation as through Maximin, whose tender and divine verses heralded beyond any valid measure, although he himself had attached “no special importance” to them.

His lively voice taught those who were desperate about his death about the folly of their pain and the greater necessity of the "early ascent". Now one can only prostrate before him and pay homage to him, which has prevented human shyness during his lifetime. The myth of the Maximin fabric enabled George to realize his previously unfulfilled religious ideas. Maxim as the embodiment of God confirmed his conception of inner-worldly transcendence . The Seventh Ring in particular illustrates the religious dimension in the work and in the development of the poet himself. First, it justified the hymn-like tone and justified the poet's claim to appear as a seer . It was also the metaphysical ground on which he could proclaim his values in a sometimes unusual style. In the lines "On the dark ground of eternity / Your star now rises through me." He himself clarifies his position as a medium by making the arrival of God possible through him.

While George had already sanctified poetry in his early work and consecrated the office of poet as a priest, it was only in the Seventh Ring that the cult developed . Between him and the early work stands as a transition the carpet of life , which in the prelude points to the ring and the star of the covenant . When George became aware of the divine mission and the priestly office not only as demands but as reality, a change from the aesthetic to the ethical took place. This is reflected in the cultic character of the Seventh Ring, the lyrical basis of the George Circle as a cultic elite. Georges did not reject Christianity , but made use of a number of its symbols and wanted to interpret it in his sense. In contrast to the Christian revelation religion, his religion was a cult religion in which the image of God is shaped by the respective actions of individual people and a religious practice.

For George the world was a sensual reality, not a transcendent numen . At an early age he tried to play off their materiality against an abstract and sublimated religion. The need to attach them to plastic figures - also the telling title of the second circle - shows itself in figures such as Algabal and culminated in the incarnation of God as an act of sanctifying the sensual body. For him this was the office of the world mother , the “great nurse in anger”, as it is called in the Templar poem , who deifies the body and embodies the god in Maximin.

Historical role model

The mythization of Maximin is based on a historical model from the Roman imperial period , which is illuminating despite certain differences and legendary uncertainties. Antinous , the beautiful favorite boy of the Emperor Hadrian , fell into the Nile in 130 and drowned. Even if it is uncertain whether it was an accident, suicide or a victim, Hadrian made him a god and created a far-reaching cult. At the place of death he founded the city of Antinoupolis , to which he named his friend, and placed him among the stars. The visual artists of that time also took up the topic and created a number of Atinous sculptures. Not only the early death, which befell Maximilian and Antinous, corresponds to the model of the godly favorite who was raptured at an early age. In his preface, George stated that Maximin had been recognized as the actor of an "almighty youth" who, the closer one got to know him, reminded the circle of a mental image , an explanation that points to the mythical character of creation by the preformed The idea of God was more decisive than the legendary person himself, who was only taken important as an occasion and carrier of the mental image.

Charismatic rule

As significant as the Maximin worship was for the poetry of George and his students, it is uncertain to what extent the cult shaped the practical life of the George circle. While the friends in the older George circle viewed the myth as a personal experience of the poet and evaluated it differently, the actual circle of disciples , which had come together as a cult community to form a male alliance of a religious elite, sometimes submitted to it uncritically. Within this circle, the myth assumed a central position.

The cult also shaped the development of the concept of charismatic rule by Max Weber . For him, the George Circle had many characteristics of such an association. Since 1910 Weber had increasingly occupied himself with the question of the relationship between the individual and the group. Every order should be examined to determine "which human type it gives, through external or internal (motive) selection", the best opportunity to rise to rulership. In this context, the term charisma appeared for the first time in a letter to Dora Jellinek in June 1910 . The “Maximin cult” is characterized by the “need for redemption”. Five months later he wrote that the circle had the characteristics of a sect and "thus also the specific charisma of such a".

In science, everything depends on asking the right questions. For Weber, the artistic sects were among the most interesting objects of investigation, as they had "just like a religious sect their incarnation of the divine." In a speech given in the same year, he explicitly spoke of the George Circle as a sect: "... I remember to the sect Stefan Goerges ... ”, emphasizing that he used the term value-free.

In his fundamental essay The Three Pure Types of Legitimate Rule , which was first printed in the Prussian Yearbooks in 1922 , Weber distinguished between three ideal types : The legal rule based on statutes, according to which the law can be created and changed in a formally correct procedure, the traditional one Rule based on belief in the sanctity of orders that have always existed, the purest type of which is patriarchal rule and charismatic rule , "by virtue of affective devotion to the person of the Lord and their gifts of grace." The type of charismatic rule was first proposed by Rudolph Sohm for the early Christian Congregation, albeit without realizing that such a category was involved.

Weber's charismatic gifts include magical abilities, revelations or heroism, as well as the power of spirit and speech. The purest types of this rule are those of the prophet and the great demagogue, whose association is the "communalization of the community or the allegiance". While the type of the commanding is that of the leader , that of the obedient is found in the disciple , who follows the leader because of his extraordinary qualities. This willingness, according to Weber, only lasts as long as these qualities are ascribed to him and his charisma is proven. If the god leaves him, his rule collapses. For Thomas Karlauf , against this background, the structures of the circle with Weber's charisma concept can be well described.

Nietzsche's influence

In this context Nietzsche's influence on George is also important, which has been emphasized many times.

George's view of history was based on Nietzsche's monumental history , which Nietzsche had placed alongside the antiquarian and critical ones in the second part of his out-of- date considerations On the benefits and disadvantages of history for life , and whose standard was Plutarch's descriptions of the lives of great people from Greek and Roman antiquity. The past can be interpreted from the highest power of the present: “Satisfy your souls in Plutarch and dare to believe in yourself by believing in his heroes”. So man as “active and striving” hopes for an eternal, over The connection that existed in the times, because what was once able to “expand the concept of human beings further and fulfill them more beautifully”, must “exist forever.” In the sense of this ghostly conversation, the great moments of the individual connect and form a chain like a “bridge over the desert Stream of becoming ”, which connects the mountain range of humanity through millennia. This insight spurred him on to great achievements, because the outstanding things of the past were possible and thus also achievable later.

George's prophetic role in the follow-up to Nietzsche is made clear in the time poem of the first part, which is characterized by the pathos of high responsibility and to which the poet's distance from the “stupid (e)” “trot (end) crowd” in the lowlands can also be noted like his great overview. In visionary perspectives, he compares Nietzsche with Christ , "shining before the times / like other leaders with the bloody crown", as the "savior who cries out" in the "pain of loneliness".

At the latest with the seventh ring , George presented himself in the role of the strict legislator in his own artificial realm. Herbert Cysarz , for example, who had met George through Gundolf, reported that the poet had declared himself "the willful founder of an artistic state."

George tried to explain the shameful end of Nietzsche also with his isolation, with the flight into the spiritual heights of “icy rocks” and “horste horrible birds.” So he believes he has to posthumously call out to the great dead man “pleading” that loneliness offers no solution and it is “necessary” to “capture yourself in the circle that love closes ...”. For the poet himself, this was his own circle of disciples, whom he gathered around himself and in which he set the tone. This went so far that the circle created the myth that George himself was the only legitimate Nietzsche descendant, redeeming the visions of the Praeceptor Germaniae.

In his ring , George also deals with motifs of the hostility to the body criticized by Heinrich Heine and his admirer Nietzsche . Saint-Simon's doctrine , which was taught by his pupil Enfantin as a living unit of spirit and material and can be found as a leitmotif in Nietzsche - for example in his curse on Christianity - is taken up in the Templar poem of figures . While Nietzsche recommended the innocence of the senses against the contempt for the body of a certain ascetic Greco-Christian tradition , George's formula at the end of the poem reads: "Divine the body and incorporate God", thus reflecting the teaching of Enfantin.

Imitatio and homosexuality

George distinguished between artists, whom he called primordial or primordial spirits , from derived beings . While the primal spirits were able to complete their systems without guidance, the work of the others was not self-sufficient, so that they were dependent on contact with the primal spirits and could only receive the divine in a derivative form. The opposing pair of primordial spirits - derived beings shaped the thinking and work of the George Circle.

Rudolf Borchardt was regarded as derived for Gundolf, while George himself was "nothing but being". Max Kommerell made a distinction between the original poet, who created new language signs directly from the material of life (mimesis) and the derived poet, who "continued to form" (imitatio). Most of George's followers saw themselves as derived beings.

As George explained to Hofmannsthal's critical objections, these derived beings should take part in and participate in the creative achievements of the primordial spirits through an ethically and aesthetically specific way of imitation. For George, Karl Wolfskehl and Ludwig Klages were among the few original spirits. The actual creation, the Creatio, does not refer to a new creation of the world, as in French symbolism , but to the language with which the world is described. The poet finds new signs for what is perceived, performing mimesis with which the archetypal being is recognized and represented. The derived beings, on the other hand, can write poetry in the gesture of the primal spirits, but cannot themselves accomplish any creation. Conflicts arise when followers mix up the levels or misperceive works.

Hofmannsthal, whom Gundolf later counted among the derived beings , criticized this imitation model. It seems mendacious, it pretends to be “penetrated, to win over the whole” by using the “new tone”. The mediocre poets George messed with would only want to hide their own mediocrity by imitating the Master. George, for his part, reproached Hofmannsthal for conforming to the crowd, getting involved with many and always avoiding working with him. George's poem The Rejected was related to Hofmannsthal in the circle, while George himself did not allow himself to be committed to this interpretation.

A specific aesthetic experience constituted the George Circle and stood at the beginning of every contact between the later member and George himself. It thus preformed a quasi-religious relationship between master and disciple, a relationship that was to be continued through various imitation techniques of the circle. The impulse for this succession was triggered by an aesthetic first experience with George's poetry, which led to the unconditional recognition of his person and his work, as can be seen in the district's memory books. This is particularly evident in Gundolf, the first from George's circle to take on a younger role.

To understand the meaning of imitation and epigonality , it is important to look at the processing of homoerotic moments. While epigonality was rejected within the circle, a specific imitation was among its basic elements. According to Gunilla Eschenbach, an unsatisfied (heterosexual) love relationship played a role in the Sad Dances of the Year of the Soul , which in the prelude to the carpet is replaced by the homoerotic eros of the angel. At the same time, George replaced the negative epigonality with a positive imitation: the angel is the leader of the poet, who in turn gathers disciples around him, a paradigm shift that characterizes the beginning of the work and, looking back critically, refers to the epigonal female paradigm in the year of the soul . The non-domesticated female sexuality poses a threat to George: He combines the fulfilled (heterosexual) sexual act with decomposition and decadence - in the figurative sense with epigonality or aestheticism. In Die Fremde, for example, a poem from the carpet of life , the woman sinks into the peat as a demonic witch singing in the moonlight with her “open hair”, leaving a “boy”, “black as night and pale as linen” as a pledge while In the thunderstorm classified as a linguistically unsuccessful thunderstorm, the “wrong wife” who “romps in the weather” and “unrestrained rescue” is finally arrested.

In the seventh ring , George reversed a topos of clichéd homosexuality criticism of "feminine behavior" and turned it against the group of aestheticists by reproaching them with an "arcadian whisper" and "slight pomp", an effeminate attitude towards the "masculine" Ethos of fact could not exist. He associated “the feminine” with epigonality and aestheticism that had to be fought.

interpretation

A conversation between George and Edith Landmann is illuminating for Vincent J. Günther about the interpretation of the cycle . While life seems tamed in the carpet , the chaotic breaks in again in the ring . Something as uniform as the Stern des Bund could only have emerged "where such chaos had preceded." Now, several times have been referred to the problems of the tape, its contradictions and a certain artistic arbitrariness of various levels of style. But even Borchardt, in his polemical review, emphasized the tectonically ordered structure of the seventh ring . It was precisely the striking mathematical structure that earned George a number of reproaches. Against this background, Günther believes that the word “chaos” does not fit in with a book that has such an eye-catching, formally closed structure like no other book in German poetry. According to George himself, he wanted to organize the many currents of life and spirit and strive for a different inner unity with which he approached the world. In this sense the ring differs from previous works. If there - in the sense of aestheticism - everything inartificial and the social area have apparently been excluded, the view of totality becomes clearer here. With the exception of dream darkness , the titles of the seven circles do not awaken any association with the chaotic, but rather point to order and clarity.

A defining element of the work is the ordering principle of the antinomy , an already formative basic pattern of George's oeuvre, which one could indicate with the contrasts of intoxication and light, Nordic fog and Mediterranean clarity. This is evident not only in the polar figures , but also in the poems of time . There Nietzsche, who, despite all admiration, also has critical tones, is contrasted with the great role model Dante , who not only designed the Paradiso but also the Inferno . If one of the principles were to be absolute, one would not do justice to the artistic intention in that certain contradictions were irrevocable and belong to the state of the world. Günther suggests for the poem Der Kampf that a simple dichotomous, judgmental separation is wrong : By describing the event from the point of view of the inferior monster and not of the god of light and the person lying on the ground still having the power of song, one forbids himself clear interpretation in terms of victory.

The antinomic tensions of the ring can also be demonstrated in earlier works, even though they were clearly articulated for the first time in the ring . George includes historicity with its contradictions and distortions in his work, without giving up the aesthetic. For Günther it is not about aesthetic reconciliation , but about a profound design of the Eternal Moment , which corresponds to the Greek Kairos , a special moment that does not sink into the flow of time, but transcends it. Conveying the contradictions, harmonizing the world is fatal.

George's verdict on time concerned elements of the Wilhelmine era and could not be understood as a reactionary reckoning with liberalism . For Günther, his poetry is not anti-democratic but opposes the (postmodern) careless copying of objective opposites. By viewing history as a stage for conflicting forces, George is unable to see in it any dialectical process of becoming a definable goal.

His relationship to tradition also appears in a new light and leads to an ideal simultaneity of the epochs, which can be related poetically to one another despite their contrasts. In this way, the person also appears from a different perspective. George rejects the common idea of individuality. Man can only endure the contradictions of the world if he does not cultivate his accidental properties, but circumcises them. As George now turns away from the cult of individuality , the path to the formation of the community is pre-marked: The Seventh Ring is the poetic foundation of the George Circle .

For Günther, the eternal moment in which the opposites of the world can be understood is echoed in the famous last poem of the Maximin cycle, the rapture - "I feel air from another planet." Although the poet in the usual style of mystical experiences the rise of the I sing about it, there is no Unio mystica, as one would have expected in the final poem, but a dissolution (“I dissolve myself in tönen”).

The experience of the Eternal Moment does not lead to enlightenment, does not release any poetic original words that could still be expressed. By letting art limit the unspeakable, George takes his work to the limit of silence. The seventh ring refutes “the possibility of a sayable myth in the modern world. It is poetry from the end of poetry. "

reception

The poetry of George and his circle has been criticized many times, even polemically panned out, while the circle for its part did not skimp on defenses, art-theoretical explanations and polemics and was based on the specific imitation model explained above , which the artist's original creation of the processing of derived beings difference.

Georg Simmel , an aesthetic philosopher in the tradition of the philosophy of life and representative of the learned Jewish bourgeoisie, published the essay Stefan George in the future in 1898 . An art-philosophical consideration that is considered to be the first attempt to interpret George's poetics in an art-philosophical way and to develop the main features of modern poetry in the poet's work . His student Margarete Susman supplemented this approach and introduced the term of the lyrical self that is still used today, using Georges as an example .

The Seventh Ring is undergoing a compelling artistic development, driven by “dark root forces that don't know where” and shows a clear line of growth. This development does not mean that later works are more perfect and richer than those of the early period, but rather testifies to a plan beyond consciousness and unconsciousness. Simmel went so far as to use Plato's theory of ideas , the philosopher who, along with Holderlin, became increasingly important for the George circle. He compares the artistic development as it has shown itself in the works of the last few years with the gradual unfolding of the Platonic idea. His poetry is fed solely from his soul, which sings only to itself, not the outside world. No lyric poet would live out of himself in such a compelling metaphysical sense and shape it like George. In all objective being that is taken into the work, it is only the one soul that plays itself in distributed roles.

Rudolf Borchardt was known for his sometimes polemical pamphlets and had previously been close to the circle himself, but then distanced himself. With its program a creative restoration of German culture from the traditional inventory of western worlds of form he was among the opponents of change, of language decay and anarchy of modes and joined the calls for a conservative revolution of the revered Hofmannsthal, which this in his famous writings speech prepared would have. In 1909 he published the essay Stefan George's Seventh Ring in the yearbook Hesperus , with which he subjected the work to sharp criticism.

After a negative overall assessment at the beginning, he goes on to mostly reject but also praise individual poems. He vehemently criticizes the gap between poetic ability and fame and asks provocatively whether there is a stronger affirmation of the divine in the world than the fact, reminiscent of a doctrine of salvation, that the works are nothing compared to faith. In no literature in the world has it been possible so far that someone with demonic means, albeit “without skills and art”, forced the immoderate soul of a generation into the shape of his inner being, a state in which he himself existed. There is no second time to find a “classic of a nation” who does not master the laws of language and is not sure of grammar or taste, but still “has imposed this language ... gigantically on a new era” and can boast of it . The strange number mysticism also dominates the order in a more naive, artificial-external than artistic-composing way and does not obey any internal plan. Only the fourteen opening poems of time would constitute an adequate unit. Some of the (earlier composed) songs that George lets follow the dream darkness are beautiful, of poignant simplicity, classic outline and an unearthly magic of the guided singing, evidence of a great mastery, a great soul like the poet has never seen in any other book have found. This includes the song Im windes-weben , which was also highlighted by Adorno.

George's homosexuality and its importance within the circle played a role in several discussions. In a letter to Hofmiller, Rudolf Alexander Schröder initially called the productions of the George Circle the "poor caricature" of "sterile pre-Affaeliteism." Against the background of the polemical Borchardt review of the seventh ring , he settled with George's complete works and mixed homophobic and nationalistic ones Sounds. The national shrine of Goethe is polluted: "We would have remained silent if George's latest publication hadn't done a shrine with hands that we can no longer call pure, the keeping of which is a matter for the German nation to keep clean." This sanctuary would be tainted by homoeroticism, hinted at in the male pair of friends in Goethe's poem Last Night in Italy , with which George would later open his last cycle, The New Kingdom . Schröder emphasizes this “not very clean object” by referring to Maximin and the Seventh Ring.

Friedrich Gundolf , apologetic admirer and student of George, saw his historical task as the “rebirth of the German language and poetry.” He wrote of the “only two people beyond this entire age ... who discharge themselves in words about their historical occupation to fulfill the renewal: Nietzsche and George. "

The appearance of the angel in the carpet of life is proclamation and not epiphany . Gundolf tried to explain his program of the deification of the body with reference to Plato's Symposium and Phaedrus in his own interpretation, which combines the “German heroic cult” with elements of Platonic love .

For George Maximin was the embodiment of the idea of beauty and not only forms the center of the Seventh Ring , but also the core of George's other work. Whoever is able to recognize the deity not in “all eternity, but in every moment”, the deification of the body is understandable. If you discover the real origin of the poems, don't be astonished to find a “god-human figure” in George's Hellenic Catholic world. So be Maximin "no more and no less perfect than the divine simply beautiful person to wonder born in this particular hour ... not a superman, not a prodigy, that is aperture human ranks, but just a God , release human rank. "

The “heroic cult of antiquity from Heracles to Caesar” is only a “duller form” of the Platonic doctrine. So far, if every genuine belief is “the deification of man as a matter of course” and only “the physical appearance of a mediator is absurd for a bloodless and soulless generation”, “the real secret of George's belief lies in the deification of a young German man of that time”.

With this interpretation, Gundolf reveals an emerging German youth worship at the time. The "German youth" is a world force that differs from the youth images of other peoples, a spiritual and sensual archetype of "humanity" that has not appeared since the death of Alexander the Great , in classical Greece, where youth is not just a natural state , but was spiritually.

The fact that “a man falls in love with boys instead of girls” belongs “in the realm of natural blood stimuli, not of the spiritual life forces.” However you evaluate it - apologetically as a detour of nature or approvingly as its refinement - this infatuation has with “ Love to do as little as the sexual act. ”In his much-quoted introduction to the rephrases of Shakespeare's sonnets, George wrote not only of“ adoration for beauty and the glowing urge to perpetuate ”, but also“ the poet's passionate devotion to his friend ” the “world-creating power of cross-sex love” explained. You have to accept this. It is foolish "to stain with blame as with salvation what one of the greatest earthly people found good."

In his review of Stefan George in 1933 , Walter Benjamin went into a study by Willi August Koch and emphasized the poet's prophetic voice right from the start . Similar to Adorno later, he attested that he had prior knowledge of future catastrophes, which, however, referred less to historical than to moral contexts, the criminal courts that George had predicted the “sex of the hurryers and gawkers”. As the finisher of decadence poetry, he was at the end of a spiritual movement that began with Baudelaire .

With his innate instinct for the night, however, he was only able to prescribe rules remote from life. For him, art is the seventh ring with which the order that yields in the joints should be forged together.

For Benjamin, George's art turned out to be strict and cogent, the "ring" narrow and precious. However, he had the same order in mind that the "old forces" had striven for with less noble means. Responding to Rudolf Borchardt's criticism of misguided stanzas, Benjamin dealt with specific problems of the style that displace the content or eclipse it. Works in which George's strength has failed are mostly those in which style triumphs, Art Nouveau , in which the bourgeoisie camouflages their own weakness by cosmically rising up, raving in spheres and abusing youth as a word. The mythical figure of the perfecter Maximin is a regressive, idealizing defensive figure. With its “tormented ornament (s)”, Art Nouveau wanted to lead the objective development of forms in technology back into the arts and crafts. As an antagonism , it is an “unconscious attempt at regression” to avoid the upcoming changes. A look at George's experience of nature is enlightening to recognize the historical workshop in which the poetry was created. For the “farmer's son” nature remained a superior and present power after he had long lived as an urban writer in big cities: “The hand that no longer clenches around the plow clenched in anger against it.” The forces of George's origins and later life seem to be in a constant conflict. For George, nature "degenerated" to the point of total de-divinization. A source of George's poetic power is therefore to be sought in the verses about the angry "great nurse" nature ( Templar ) from the Seventh Ring .

Thomas Mann had dealt with the George School and the Dante cult of the poet in an ironic and critical way, for example in Gladius Dei and Death in Venice .

In his short story, The Prophet , he processed impressions of a reading by the George student Ludwig Derleth , who is portrayed as the character Daniel zu Höhe , whose "visions, prophecies and words of the order of the day ... in a style mixture of psaltery and revelation sound" by a disciple be presented. “A feverish and terribly irritated self rose up in lonely megalomania and threatened the world with a torrent of violent words.” Daniel zur Höhe also plays a supporting role in the great contemporary novel Doctor Faustus as a participant in the discussion groups and discursive men's evenings in the apartment of Sixtus Kridwiss . He was often mistaken for Stefan George himself or Karl Wolfskehl. Right at the beginning of the novel, Thomas Mann varied a verse from George's time poem , thereby referring to the central name Nietzsche , which is not mentioned in the book itself. Is in George's first stanza: "And went from a long night to the longest night". Thomas Mann says: "... two years after Leverkühn's death, that is to say: two years after he went from the deepest night into the deepest". In his verses, George linked hope and danger with Nietzsche's name and thus reflected the legend to which Thomas Mann clung to all his life despite all the refractions.

Thomas Mann praised the Nietzsche poem he took up as “wonderful”, but stated that it was more characteristic of George than Nietzsche himself. One would misunderstand and diminish the cultural significance of Nietzsche if one wished that he was himself instead of Master of German prose “only” as a poet should have fulfilled. The influence on the intellectual development of Germany is not characterized by works such as the Dionysus dithyrambs or the songs of Prince Vogelfrei , but by the outstanding prose of the master stylist.

Resistance and Secret Germany

Many intellectual and cultural-historical effects emanated from George and his circle, for example on the German resistance . For Count Claus von Stauffenberg , who later belonged to the district, they were of great importance.

In 1923 the twin brothers Alexander and Berthold , shortly afterwards Claus, were introduced to the poet and introduced to the circle. In 1924 he wrote to the poet how much his work had shaken and roused him. The letter shows the intellectual development of the young Stauffenberg as well as his willingness to act for secret Germany . He read a lot in the year of the soul , and passages that initially seemed distant and intangible to him "first sounded like that and then with your whole soul" nestled in his senses. “The clearer the living” stands in front of him “and the more vividly the act shows itself, the more distant the sound of one's own words and the rarer the meaning of one's own life”.

Stauffenberg, who belonged to the third generation of the circle, in his early poetry mainly imitated poems from the Seventh Ring , as well as the Shepherd and Prize poems and the year of the soul . So he admonished his brother Alexander with a saying whose style and apodictic instructive tone is based on the four-line tables that form the end of the ring and in which there are different lengths of verse in the iambic meter.

Stauffenberg was later reinforced in his resistance to Adolf Hitler , especially by the poem Der Widerchrist with his warning against the “Prince of the bugger” and recited it several times in the days before the assassination attempt of July 20, 1944 . Also Henning von Tresckow read the poem with friends, and the British threw it during the war as a leaflet from about Germany.

As Gerhard Schulz notes, the verses about the false prophet can be read like no other poem known to him as a prophecy of the “self-destruction” chosen by the Germans during the time of National Socialism .

For Bernd Johannsen, George warns in these lines of the coming demagogue , who sets his own political rights, the Dionysian seducer, whose aesthetic of death runs counter to George's actual ideal of beauty. It is the antichrist and criminal god from the poem The Hanged Man of the New Kingdom . There the convicted man, who is being led to the place of execution, looks into the crowd and sees in the eyes of the stone-throwing spectators - anticipating sociological theories of punishment and reflecting on Nietzsche's psychology - his own secret desires, which are still suppressed by fear and which are to be banished in the criminal.

The Secret Germany , title of a complex poem of the last geschichtsprophetischen cycle and first as a term of Karl Wolfskehl in the Yearbook of the spiritual movement used is a secret and visionary construct. It lies hidden beneath the surface of real Germany and represents a force that, as its undercurrent, remains secret and can only be grasped pictorially. Only the capable can recognize it and make it visible. It is a mystical transfiguration of Germany and the German spirit, which is based on a sentence from Schiller's fragment German Greatness : "Every people has its day in history, but the day of the German is the harvest of all time." can also be understood as a mythical politeia of German intellectual greats of all times, as the idea of a German cultural nation and bearer of the German spirit and in this way forms the opposite pole to the current state. The New Kingdom resides in him like a Platonic idea , the content of which is based on the interpreters, who usually come from George's environment.

As an aesthetically oriented men's association, the George Circle wanted to interpret and preserve the German spirit in a way that Schiller's aesthetic education was committed to. In this sense, he shaped the story in a way that was revealed in the assassination. For this reason alone, George could not have been an ancestor of National Socialism.

literature

Text output

- Stefan George: The seventh ring . Verlag der Blätter für die Kunst, Berlin 1907 (first edition as private print; full text online at Wikisource ).

- Stefan George: The seventh ring. (= Complete Works , Volume VI / VII). Edited by Ute Oelmann. Klett-Cotta, Stuttgart 1986 (annotated study edition ).

Secondary literature

- Walter Benjamin: Review of Stefan George ; To a new study of the poet. In: Hans Mayer (ed.): German literary criticism. From the Third Reich to the present (1933–1968). Fischer, Frankfurt 1983, pp. 61-68.

- Rudolf Borchardt: Stefan Georges Seventh Ring. In: Rudolf Borchardt: Collected works in individual volumes. Prose I. Edited by Marie Luise Borchardt. Klett-Cotta, Stuttgart 1992, pp. 258-294.

- Gunilla Eschenbach: Imitatio in the George circle. De Gruyter, Berlin 2011, ISBN 978-3-11-025446-4 .

- Vincent J. Günther: The Eternal Moment. On the interpretation of George's “The Seventh Ring”. In: Eckard Heftrich (Ed.): Stefan-George-Colloquium. Cologne 1971, pp. 197-212.

- Bruno Hillebrand: Nietzsche manual, life - work - effect. Literature and Poetry, Stefan George. Metzler, Stuttgart / Weimar 2000, ed. Henning Ottmann, p. 452.

- Bernd Johannsen: Realm of the Spirit. Stefan George and Secret Germany. Publishing house Dr. Hut, Munich 2008.

- Thomas Karlauf: Stefan George. The discovery of the charism. Karl-Blessing-Verlag, Munich 2007, ISBN 978-3-89667-151-6 .

- Hansjürgen Linke: The cultic in the poetry of Stefan Georges and his school. Helmut Küpper, Munich / Düsseldorf 1960.

- Ernst Osterkamp : Poetry of the Empty Center. Stefan Georges New Reich (= Edition Akzente ). Carl Hanser Verlag, Munich 2010, ISBN 978-3-446-23500-7 ( table of contents , table of contents ).

- Manfred Riedel : Secret Germany. Stefan George and the Stauffenberg brothers. Böhlau Verlag, Cologne / Weimar / Vienna 2006, ISBN 3-412-07706-2 ( table of contents ).

Web links

- The seventh ring at Zeno.org .

Individual evidence

- ^ Ernst Osterkamp, Poetry of the Empty Center , Stefan Georges Neues Reich, Carl Hanser Verlag, Munich 2010, p. 42.

- ^ Hansjürgen Linke, The cultic in poetry by Stefan Georges and his school, The titles of poetry collections , Helmut Küpper, Munich and Düsseldorf 1960, p. 20.

- ↑ The seventh ring. In: Kindlers Neues Literatur-Lexikon, Vol. 6, Stefan George, Kindler, Munich, 1989, p. 231.

- ↑ Stefan George, The Seventh Ring , Boecklin, in: Works, edition in two volumes, Klett-Cotta, Volume I, Stuttgart 1984, p. 233.

- ↑ Stefan George, The Seventh Ring, Leo XIII. In: Werke, edition in two volumes, Klett-Cotta, Volume I, Stuttgart 1984, p. 236.

- ↑ Stefan George, The Seventh Ring , Goethe Day , in: Works, edition in two volumes, Klett-Cotta, Volume I, Stuttgart 1984, p. 230.

- ↑ Stefan George, The Seventh Ring, Nietzsche. In: Werke, edition in two volumes, Klett-Cotta, Stuttgart 1984, p. 232.

- ↑ Stefan George, The Seventh Ring, Die tote Stadt , in: Werke, edition in two volumes, Klett-Cotta, Volume I, Stuttgart 1984, p. 243.

- ↑ Thomas Karlauf, Stefan George, The Discovery of Charisma, Karl-Blessing-Verlag, Munich 2007, p. 362.

- ↑ Vincent J. Günther, The Eternal Moment, On the Interpretation of Georges “The Seventh Ring” , in: Stefan-George-Colloquium, Ed. Eckard Heftrich, Cologne 1971, p. 198.

- ^ Stefan George, The Seventh Ring, Der Widerchrist , edition in two volumes, Klett-Cotta, Volume I, Stuttgart 1984, p. 258.

- ↑ Thomas Karlauf, The beautiful life, Stefan George, The discovery of charisma, Karl-Blessing-Verlag, Munich 2007, p. 272.

- ↑ Stefan George, The Seventh Ring, Gezeiten , in: Works, edition in two volumes, Klett-Cotta, Volume I, Stuttgart 1984, p. 263.

- ↑ Stefan George, The Seventh Ring, Umschau , edition in two volumes, Klett-Cotta, Volume I, Stuttgart 1984, p. 263.

- ↑ Stefan George, The Seventh Ring, conclusion , in: Works, edition in two volumes, Klett-Cotta, Volume I, Stuttgart 1984, p. 271.

- ^ Killy Literature Lexicon , Stefan George, volume. 4, p. 119.

- ↑ Stefan George, On the life and death of Maximins. In: Stefan George: Works, edition in two volumes, Volume I, Klett-Cotta, Stuttgart 1984, p. 284.

- ^ Friedrich Sieburg, Stefan George , Zur Literatur, 1957 - 1963, Deutsche Verlags-Anstalt, ed. Fritz J. Raddatz, Stuttgart 1981, p. 31.

- ^ So Adorno in: Aesthetic Theory , Collected Writings, Volume 7, p. 31.

- ^ So Theoder W. Adorno in: Notes on literature. Speech on Poetry and Society, Collected Writings, Volume 11, p. 64.

- ^ So Rudolf Borchardt: Stefan Georges Seventh Ring. In: Rudolf Borchardt, Collected Works in Individual Volumes, Prose I, Ed. Marie Luise Borchardt, Klett-Cotta, Stuttgart 1992, p. 263.

- ↑ Stefan George, The seventh ring, Im windes-weaving , edition in two volumes, Klett-Cotta, Volume I, Stuttgart 1984, p. 309.

- ^ So Manfred Riedel: Secret Germany. Stefan George and the Stauffenberg brothers. Böhlau Verlag, Cologne 2006, p. 147.

- ↑ Hansjürgen Linke, The cultic in the poetry of Stefan Georges and his school , love, Helmut Küpper, Munich and Düsseldorf 1960, p. 37.

- ↑ Quoted from: Thomas Karlauf, Stefan George, The discovery of charisma , Lauter Abschiede, Karl-Blessing-Verlag, Munich 2007, p. 132.

- ↑ Quoted from: Thomas Karlauf, Stefan George, The Discovery of Charisma , Karl-Blessing-Verlag, Munich 2007, p. 279.

- ^ Thomas Karlauf, Stefan George, The discovery of charisma , Karl-Blessing-Verlag, Munich 2007, p. 281.

- ^ Friedrich Gundolf, George, The Seventh Ring , Second Edition. Georg Bondi Verlag, Berlin 1921, p. 237.

- ↑ Thomas Karlauf, Stefan George, The discovery of charisma , Karl-Blessing-Verlag, Munich 2007, p. 361.

- ↑ Stefan George, preface to the second edition, in: Werke, edition in two volumes, Klett-Cotta, Stuttgart 1984, p. 119.

- ^ Ernst Osterkamp, Poetry of the Empty Center, Stefan Georges Neues Reich , Carl Hanser Verlag, Munich 2010, p. 42.

- ^ Ernst Osterkamp, Poetry of the Empty Center, Stefan Georges Neues Reich , Carl Hanser Verlag, Munich 2010, p. 43.

- ↑ On the “Cosmic Crisis” in different interpretations Stefan Breuer : Aesthetic Fundamentalism. Stefan George and German Antimodernism , Wissenschaftliche Buchgesellschaft, Darmstadt 1995, pp. 37–39 (psychological interpretation); Thomas Karlauf : Stefan George. The discovery of charisma , Blessing, Munich 2007, pp. 331–335; Rainer Kolk: literary group formation. Using the example of the George Circle 1890–1945 , Max Niemeyer, Tübingen 1998, pp. 90–92, both of which emphasize the ideal differences.

- ↑ Shiver. In: Historical Dictionary of Philosophy, Volume 8, p. 1225.

- ↑ Thomas Karlauf, Blutuchte, Stefan George, The Discovery of Charisma, Karl-Blessing-Verlag, Munich 2007, p. 327.

- ↑ Quoted from Thomas Karlauf, Blutuchte, in: Stefan George, The discovery of charisma, Karl-Blessing-Verlag, Munich 2007, p. 328.

- ^ Thomas Karlauf, Blutuchte, Stefan George, The discovery of charisma, Karl-Blessing-Verlag, Munich 2007, p. 332.

- ↑ Thomas Karlauf, Notes, Stefan George, The Discovery of Charisma, Karl-Blessing-Verlag, Munich 2007, p. 699.

- ↑ Thomas Karlauf, Stefan George, The discovery of charisma , blood light, Karl-Blessing-Verlag, Munich 2007, p. 331.

- ↑ Thomas Sparr, Karl Wolfskehl, in: Lexicon of German-Jewish Literature, Metzler, Stuttgart 2000, p. 629.

- ↑ Stefan George, Der Stern des Bunds, edition in two volumes, Klett-Cotta, Volume I, Stuttgart 1984, p. 365.

- ↑ Quoted from Thomas Karlauf, Blutuchte, in: Stefan George, Die Entdeck des Charisma, Karl-Blessing-Verlag, Munich 2007, p. 333.

- ↑ On this psychological interpretation Stefan Breuer: Aesthetic Fundamentalism. Stefan George and German anti-modernism. Darmstadt 1995, pp. 39-44.

- ^ So - in pluralis maiestatis - Stefan George: Preface to Maximin [1906], in: Stefan George: Tage und Taten. Notes and sketches (= Complete Works , Volume XVII), edited by Ute Oelmann, Klett-Cotta, Stuttgart 1998, pp. 62–66, here p. 62.

- ↑ Stefan George: You always start us. In: Stefan George: Der Stern des Bundes [1913] (= Complete Works , Volume VIII), edited by Ute Oelmann, Klett-Cotta, Stuttgart 1993, p. 8.

- ^ Manfred Riedel, Secret Germany, Stefan George and the Stauffenberg Brothers , Böhlau Verlag, Cologne 2006, p. 150.

- ^ Stefan George, preface to Maximin. In: Stefan George: Works, edition in two volumes, Volume I, Klett-Cotta, Stuttgart 1984, p. 522.

- ^ Stefan George, preface to Maximin. In: Stefan George: Works, edition in two volumes, Volume I, Klett-Cotta, Stuttgart 1984, p. 525.

- ^ Stefan George, preface to Maximin. In: Stefan George: Works, edition in two volumes, Volume I, Klett-Cotta, Stuttgart 1984, p. 528.

- ↑ Hansjürgen Linke, The cultic in the poetry of Stefan Georges and his school, The emergence of the god Maximin , Helmut Küpper, Munich and Düsseldorf 1960, p. 117.

- ↑ Stefan George, The Sixth. In: Stefan George: Works, edition in two volumes, Volume I, Klett-Cotta, Stuttgart 1984, p. 288.

- ^ Hansjürgen Linke, The cultic in poetry by Stefan Georges and his school , Helmut Küpper, Munich and Düsseldorf 1960, p. 57.

- ↑ Hansjürgen Linke, The cultic in the poetry of Stefan Georges and his school, The emergence of the god Maximin , Helmut Küpper, Munich and Düsseldorf 1960, p. 117.

- ↑ Stefan George, Templar. In: Stefan George: Works, edition in two volumes, Volume I, Klett-Cotta, Stuttgart 1984, p. 256.

- ↑ Hansjürgen Linke, The cultic in the poetry of Stefan Georges and his school, The emergence of the god Maximin , Helmut Küpper, Munich and Düsseldorf 1960, p. 114.

- ↑ Hansjürgen Linke, The cultic in the poetry of Stefan Georges and his school, The Maximin cult , Helmut Küpper, Munich and Düsseldorf 1960, p. 129.

- ↑ Hansjürgen Linke, The cultic in the poetry of Stefan Georges and his school, The problem of the Maximin myth , Helmut Küpper, Munich and Düsseldorf 1960, p. 127 and 131

- ↑ Quoted from: Thomas Karlauf, Stefan George, The discovery of charisma, The charismatic rule , Karl-Blessing-Verlag, Munich 2007, p. 413.

- ↑ Max Weber, The three pure types of legitimate rule , sociology, world historical analyzes, politics, Alfred Kröner Verlag, Stuttgart 1964, p. 151.

- ↑ Max Weber, The three pure types of legitimate rule , sociology, world historical analyzes, politics, Alfred Kröner Verlag, Stuttgart 1964, p. 154.

- ^ Max Weber, The three pure types of legitimate rule , sociology, world-historical analyzes, politics, Alfred Kröner Verlag, Stuttgart 1964, p. 159.

- ^ Max Weber, The three pure types of legitimate rule , sociology, world historical analyzes, politics, Alfred Kröner Verlag, Stuttgart 1964, p. 160.

- ↑ Thomas Karlauf, Stefan George, The discovery of charisma , The charismatic rule, Karl-Blessing-Verlag, Munich 2007, p. 417.

- ↑ For example Bruno Hillebrand in: Nietzsche. How the poets saw him. Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, Göttingen 2000, p. 51.

- ^ Thomas Karlauf, The beautiful life, Stefan George, The discovery of charisma, Karl-Blessing-Verlag, Munich 2007, p. 275.

- ↑ Friedrich Nietzsche, On the benefits and disadvantages of history for life, untimely considerations, works in three volumes, Wissenschaftliche Buchgesellschaft, Darmstadt 1997, p. 251.

- ↑ Friedrich Nietzsche, On the benefits and disadvantages of history for life , untimely considerations, works in three volumes, Wissenschaftliche Buchgesellschaft, Darmstadt 1997, p. 220.

- ↑ Stefan George, The Seventh Ring, Nietzsche. In: Werke, edition in two volumes, Klett-Cotta, Stuttgart 1984, p. 231.

- ↑ Bruno Hillebrand in: Nietzsche Handbook, Life - Work - Effect, Literature and Poetry, Stefan George , Metzler, Stuttgart, Weimar 2000, Ed. Henning Ottmann, p. 452.

- ↑ Bruno Hillebrand in: Nietzsche Handbook, Life - Work - Effect, Literature and Poetry, Stefan George , Metzler, Stuttgart, Weimar 2000, Ed. Henning Ottmann, p. 453.

- ↑ Stefan George, The Seventh Ring, Templer. In: Werke, edition in two volumes, Klett-Cotta, Stuttgart 1984, p. 256.

- ^ Rehabilitation of Matter. In: Historical dictionary of philosophy : volume. 8, pp. 495-496.

- ↑ Quoted from: Gunilla Eschenbach, Imitatio outside the circle, De Gruyter, Berlin 2011, p. 195.

- ↑ Gunilla Eschenbach, Imitatio im George-Kreis, De Gruyter, Berlin 2011, p. 3.

- ↑ Quoted from: Gunilla Eschenbach, Imitatio im George-Kreis , De Gruyter, Berlin 2011, p. 5.

- ↑ Gunilla Eschenbach, Imitatio im George-Kreis , Part 4, Critique of Lyrik und Poetik, De Gruyter, Berlin 2011, p. 244.

- ↑ Gunilla Eschenbach, Imitatio im George-Kreis , De Gruyter, Berlin 2011, p. 12.

- ↑ Gunilla Eschenbach, Imitatio im George-Kreis , part 3, Imitatio outside the Kreis, De Gruyter, Berlin 2011, p. 194.

- ↑ Gunilla Eschenbach, Imitatio in the George Circle , Part 3, Imitatio outside the Circle, De Gruyter, Berlin 2011, p. 195.

- ↑ The presentation is based on: Vincent J. Günther: The eternal moment. On the interpretation of George's “The Seventh Ring” , in: Stefan-George-Colloquium, Ed. Eckard Heftrich, Cologne 1971.

- ↑ Quote from: Vincent J. Günther: The eternal moment. On the interpretation of George's “The Seventh Ring”, in: Stefan-George-Colloquium, Ed. Eckard Heftrich, Cologne 1971, p. 197.

- ↑ Vincent J. Günther: The eternal moment. On the interpretation of George's “The Seventh Ring”, in: Stefan-George-Colloquium, Ed. Eckard Heftrich, Cologne 1971, p. 198.

- ↑ Vincent J. Günther: The eternal moment. On the interpretation of George's “The Seventh Ring”, in: Stefan-George-Colloquium, Ed. Eckard Heftrich, Cologne 1971, p. 202.

- ↑ So by Karl Kraus , for whom George's “solemnly undulating verses” only pretend poetry and the readers fell into ecstasy as before the emperor's new clothes

- ↑ On this: Gunilla Eschenbach, Imitatio im George-Kreis , De Gruyter, Berlin 2011.

- ^ Thomas Karlauf, Stefan George, The discovery of charisma, The breakthrough , Karl-Blessing-Verlag, Munich 2007, p. 344.

- ↑ Based on : Thomas Karlauf, Stefan George, The discovery of charisma, Ahnengalerie, Karl-Blessing-Verlag, Munich 2007, p. 292.

- ^ Rudolf Borchardt, Stefan Georges Siebenter Ring , in Rudolf Borchardt, Collected Works in Individual Volumes, Prose I, ed. Marie Luise Borchardt, Klett-Cotta, Stuttgart 1992, p. 259.

- ↑ Rudolf Borchardt, Stefan Georges Siebenter Ring , in Rudolf Borchardt, Collected Works in Individual Volumes, Prose I, ed. Marie Luise Borchardt, Klett-Cotta, Stuttgart 1992, p. 263.

- ↑ Gunilla Eschenbach, Imitatio im George-Kreis , Critique of Lyrik und Poetik, De Gruyter, Berlin 2011, p. 260.

- ↑ Gunilla Eschenbach, Imitatio im George-Kreis , Critique of Lyrik und Poetik, De Gruyter, Berlin 2011, p. 261.

- ^ Friedrich Gundolf, George, Age and Task , Second Edition. Goerg-Bondi-Verlag, Berlin 1921, p. 1.

- ^ Friedrich Gundolf, George, Age and Task , Second Edition. Goerg-Bondi-Verlag, Berlin 1921, p. 2.

- ^ Friedrich Gundolf, George, The Seventh Ring , Second Edition. Georg Bondi Verlag, Berlin 1921, p. 204.

- ^ Friedrich Gundolf, George, The Seventh Ring , Second Edition. Goerg-Bondi-Verlag, Berlin 1921, p. 212.

- ^ A b Friedrich Gundolf, George, The Seventh Ring , Second Edition. Goerg-Bondi-Verlag, Berlin 1921, p. 205.

- ^ Friedrich Gundolf, George, The Seventh Ring , Second Edition. Goerg-Bondi-Verlag, Berlin 1921, p. 202.

- ^ Stefan George, Shakespeare Sonnette, Umdichtung, Introduction. In: Werke, edition in two volumes, Volume II, Klett-Cotta, Stuttgart 1984, p. 149.

- ↑ Walter Benjamin, retrospect on Stefan George , on a new study of the poet, in: Deutsche Literaturkritik, From the Third Reich to the Present (1933 - 1968), Ed. Hans Mayer, Fischer, Frankfurt 1983, p. 62.

- ↑ Walter Benjamin, retrospect on Stefan George , on a new study of the poet, in: Deutsche Literaturkritik, From the Third Reich to the Present (1933 - 1968), Ed. Hans Mayer, Fischer, Frankfurt 1983, p. 63.

- ↑ Walter Benjamin, looking back at Stefan George , on a new study of the poet, in: Deutsche Literaturkritik, Vom Third Reich bis zur Gegenwart (1933 - 1968), Ed. Hans Mayer, Fischer, Frankfurt 1983, p. 666.

- ↑ cf. for example Hans R. Vaget, in "The Death in Venice", short stories, Thomas-Mann-Handbuch, Fischer, Frankfurt a. M. 2005, p. 589.

- ↑ Thomas Mann, With the Prophet. In: Collected Works in Thirteen Volumes, Volume VIII, Stories. Fischer, Frankfurt 1974, p. 368.

- ↑ Klaus Harpprecht , Thomas Mann, Eine Biographie, Im Schatten der Disease, Chapter 97, Rowohlt, Reinbek 1995, p. 1550.

- ^ Stefan George, Nietzsche. In: Stefan George: Works, edition in two volumes, Volume I, Klett-Cotta, Stuttgart 1984, p. 231.

- ↑ Thomas Mann, Doctor Faustus, Collected Works in Thirteen Volumes, Volume VI, Fischer, Frankfurt 1974, p. 9.

- ^ Eckard Heftrich, Doctor Faustus: The radical autobiography. In: Thomas Mann 1875 - 1975, lectures in Munich - Zurich - Lübeck, Fischer, Frankfurt 1977, p. 139.

- ↑ Thomas Mann, Einkehr, in: Collected works in thirteen volumes, Volume XII, speeches and essays. Fischer, Frankfurt 1974, p. 86.

- ↑ Manfred Riedel, Secret Germany, Stefan George and the Stauffenberg Brothers , Böhlau Verlag, Cologne 2006, p. 174.

- ↑ Quoted from: Manfred Riedel, Secret Germany, Stefan George and the Stauffenberg Brothers , Böhlau Verlag, Cologne 2006, p. 176.

- ↑ Gunilla Eschenbach, Imitatio im George-Kreis , Part 2: Imitatio im Kreis: Vallentin, Gundolf, Stauffenberg, Morwitz, Kommerell, De Gruyter, Berlin 2011, p. 103.