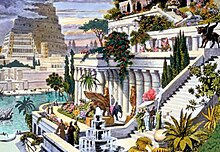

Hanging Gardens of the Semiramis

The Hanging Gardens of Semiramis , also called the Hanging Gardens of Babylon , were, according to the reports of Greek authors, an elaborate garden complex in Babylon on the Euphrates (in Mesopotamia , in today's Iraq ). They were among the seven wonders of the ancient world . The Greek legendary figure of Semiramis is sometimes equated with the Assyrian queen Shammuramat .

history

According to the ancient writers, the hanging gardens were next to or on top of the palace and formed a square with a side length of 120 meters. The terraces reached a height of approx. 25 to 30 meters. The thick walls and pillars of the superstructure were mainly made of fire bricks, and corridors are said to have been located under the individual steps. The floors consisted of three layers, one layer of pipe with a lot of asphalt , above it a double layer of burnt bricks embedded in plaster of paris , and at the top thick sheets of lead . This prevented moisture from penetrating. Humus could have been applied to this construction and various types of trees could have been planted. Irrigation was possible from the nearby Euphrates .

The descriptions to which we owe our presentation of these gardens go back to the following authors:

- Antipater of Sidon (beginning of the 2nd century BC), in whose poem about the seven wonders of the world in the Anthologia Palatina, however, no place is mentioned ("also the hanging gardens and the Colossus of Helios").

- The Chaldean Berossus (* around 350 BC), from whose lost work Babyloniaka the Jewish historian Flavius Josephus quoted in detail.

- The Greek medic Ktesias of Knidos , who around 400 BC Became a prisoner of war in Persia and was the personal physician of King Artaxerxes II . He left behind an extensive and in parts imaginative work entitled Persika . What he wrote about Babylon in it is largely lost, except for quotations in the works of Diodor and Quintus Curtius Rufus .

- Diodoros Sikulos , who wrote his description (Historien II. 10.1–6) around the middle of the 1st century BC. And quoted from a work by the Greek Ktesias of Knidos, which has since been lost. Ktesias probably served at the Persian court long before the conquests of Alexander the Great. His report is probably based on a report by the ancient Greek historian Kleitarchos . Diodoros Sikulos' report is essential because it clearly states that no mechanism was visible that carried the water upwards.

- Strabo , a Greek scholar who lived in the 1st century BC. Wrote his geography .

- Philo of Byzantium , who probably died around 250 BC. Wrote a kind of travel guide to the seven wonders of the world.

According to the general tradition, the gardens are said to have been built by Queen Semiramis , whose fame extends even today to distant Armenia, where a large irrigation canal for the city of Van (now Turkey) on Lake Van "Stream of Semiramis" and the highest part of the castle the city is called "Semiramisburg".

Diodorus protested against the opinion that was already circulating in antiquity that the gardens were built by Semiramis (II, 10, I): Rather, they were built by a Babylonian king. According to Borosus, it was Nebuchadnezzar II. His wife is said to have longed for the forests and mountains in the lowlands of Babylonia, so the king built the hanging gardens for her. Other important ancient authors who stayed in the area or report on the area do not name the gardens after Semiramis, such as Herodotus (Historien I, 181), Xenophon (Cyropaedia) and Pliny (Natural History VI. 123).

Localization attempts

In Babylon

The complex excavated by Robert Koldewey in the northeast part of the South Palace, the foundation of which consisted of several vaulted rooms, is often interpreted as the remains of the hanging gardens. This building consisted of 14 chambers. The foundation walls formed a trapezoid with edge lengths between 23 and 35 meters. The building also had a well system. Particularly noticeable were the paternoster-like structures that apparently transported water between several floors. It was found that this water came from several sources. The excavated area is assigned to Nebuchadnezzar II .

Wolfram Nagel locates the gardens in the west of the south castle, probably in the area of the outer works, and then accepts a new building in Persian times by Atossa , the mother of Xerxes I , who thus had gardens to her "great aunt Amyitas " for the Nebuchadnezzar set up, wanted to remember.

Julian Reade locates the gardens in the outer work of the so-called North Palace , facing east towards the palace.

Kai Brodersen assumes that these gardens never existed, but that an inaccessible palace garden of Nebuchadnezzar II took on ever more wonderful forms in the imagination of the authors over the centuries. As evidence, he states that these buildings could not be located satisfactorily until today, that the garden was assumed to be irrigated, which was only invented after Nebuchadnezzar II, and that neither contemporary Babylonian texts nor Herodotus report such a building. Other authors now also doubt Koldewey's interpretation, e. B. Michael Jursa .

In Nineveh

Some scholars argue that the accounts of the Hanging Gardens of Babylon actually describe the sprawling gardens of the Sennacherib palace in Nineveh and not in Babylon.

As early as the early 1990s, the Assyriologist and cuneiform writing expert Stephanie Dalley from the University of Oxford put forward arguments in favor of the interpretation that the Hanging Gardens were the palace garden of the Assyrian King Sennacherib , who lived around 100 years before the Babylonian King Nebuchadnezzar II . This palace garden in Nineveh on the Tigris was built for Sennacherib's wife Tašmetu-Šarrat and watered with an Archimedean screw . In 2013, Dalley backed up her plea for Nineveh in a book with further evidence from topographical studies and historical sources and thus caused a sensation. Dalley proposes that the relief from Kuyunjik shows the aqueduct of Jerwan .

The aqueduct is part of the great Atrush Canal, which was built by the Assyrian King Sennacherib between 703 and 690 BC to be in Nineveh a . a. to irrigate the extensive gardens with water from the Khenis Gorge diverted 48 km north.

Naming in ancient scripts

In ancient Greek , the name was οἱ [τῆς Σεμιράμιδος] Κρεμαστοὶ Κῆποι Βαβυλώνιοι hoi [tês Semirámidos] Kremastoí Kêpoi Babylônioi (in Latin, the Semiramidos gardens) or "the hanging gardens of the Semiramis" in Latin Horti Pensiles Babylonis ("the hanging gardens of Babylon"), in Arabic الحدائق المعلّقة, DMG al-ḥadāʾiq al-muʿallaqa .

Trivia

In 1989, Saddam Hussein , dictator of the Republic of Iraq , offered a price equivalent to 1.5 million US dollars to the Iraqi who could explain how the Hanging Gardens of the Semiramis were watered.

literature

- Stephanie M. Dalley: The mystery of the Hanging Garden of Babylon: an elusive world wonder traced. Oxford University Press, 2013, ISBN 978-0-19-966226-5 .

- Jean-Jacques Glassner: On the subject of the Jardins Mésopotamiens. In: Rika Gyselen (Ed.): Jardins d'Orient (= Res Orientales. Volume 3). Paris 1991, pp. 9-17.

- Robert Koldewey : Babylon Rising Again. The previous results of the German excavations. CH Beck, Munich 1990.

- Fritz Krischen : World wonder of architecture in Babylonia and Jonia. Wasmuth, Tübingen 1956.

- Fauzi Rasheed: The Hanging Gardens are the Refrigerator of Babylon. In: Masao Mori, Hideo Ogawa, Mamoru Yoshikawa (Eds.): Near Eastern Studies: Dedicated to HIH Prince Takahito Mikasa on the Occasion of his Seventy-Fifth Birthday. Wiesbaden 1991, pp. 349-361.

- Stefan Schweizer : The hanging gardens of Babylon. From the wonder of the world to green architecture. Klaus Wagenbach, Berlin 2020, ISBN 978-3-80313694-7 .

Web links

- The Seven Wonders of the World: Babylon Website of the archaeologist Kristian Büsch (as of 2007)

- The hanging gardens of the Semiramis website by Thorsten Schiemann (as of 2007)

Individual evidence

- ↑ Kai Brodersen: The seven wonders of the world. Legendary art and buildings of antiquity . CH Beck, Munich 2004, ISBN 3-406-45329-5 , p. 10 .

- ↑ Stephanie Dalley: The mystery of the Hanging Garden of Babylon: an elusive world wonder traced . Oxford 2013, p. 30.

- ↑ Stephanie Dalley: The mystery of the Hanging Garden of Babylon: an elusive world wonder traced . Oxford 2013, p. 31.

- ↑ Eckard Unger: Babylon, the holy city . Walter de Gruyter, 2012, ISBN 978-3-11-002676-4 , p. 217.

- ↑ a b Stephanie Dalley: Nineveh, Babylon and the Hanging Gardens: Cuneiform and Classical Sources reconciled. In: Iraq. 56, 1994, pp. 45-58.

- ↑ Johannes Thiele: The seven wonders of the world. Marix-Verlag, Wiesbaden 2006, ISBN 3-86539-906-1 , p. 58.

- ↑ Wolfram Nagel: Where were the "Hanging Gardens" of Babylon? In: Communications of the German Orient Society. 110, 1978, p. 26.

- ↑ Michael Jursa: The Babylonians. History. Society. Culture. CH Beck Verlag, Munich 2004, ISBN 3-406-50849-9 , p. 77.

- ^ A b Stephanie M. Dalley: The mystery of the Hanging Garden of Babylon: an elusive world wonder traced. Oxford University Press, 2013, ISBN 978-0-19-966226-5 .

- ^ Wolfram von Soden: The Ancient Orient: An Introduction to the Study of the Ancient Near East. Erdman's Publishing Company, Grand Rapids 1985, p. 58.

- ↑ Stephanie Dalley: Ancient Mesopotamian Gardens and the Identification of the Hanging Gardens of Babylon Resolved. In: Garden History. Vol. 21, No. 1, 1993, page 7.

- ↑ Stephanie Dalley: Ancient Mesopotamian Gardens and the Identification of the Hanging Gardens of Babylon Resolved . In: Garden History. Vol. 21, No. 1, 1993, 1-13.

- ↑ Cf. Tobias Dorfer: Hanging Gardens of Babylon actually existed - in Nineveh. In: Süddeutsche Zeitung . May 6, 2013.

- ↑ See The Hanging Gardens of Babylon. TV documentary (52 min.), Great Britain 2014, broadcast on arte on March 22, 2014.

- ↑ on the aqueduct cf. Christopher Jones: Assyrian Agricultural Technology. Gates of Nineveh weblog, February 15, 2012.

- ^ The Hanging Gardens of Babylon. The Kuyunjik Relief, c.650 BC. Plinia.net, private website of PE Michelli.

- ↑ The aqueduct at Jerwan in Iraqi Kurdistan. Constructed between 703 and 690 BC. Photography by Sebastian Meyer, Photoshelter.com.

- ^ Iraq Offers Prize for Solving Puzzle of Hanging Gardens. Los Angeles Times, September 8, 1989 (English) ( Memento of 23 October 2018 Internet Archive ).