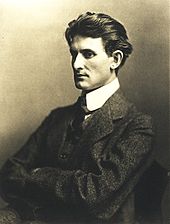

Friedrich Wolters

Friedrich Wilhelm Wolters (born September 2, 1876 in Uerdingen , † April 14, 1930 in Munich ) was a German historian, poet and translator. He was one of the central figures in the George circle .

After Wolters came into contact with Stefan George in 1904 , he was accepted into the circle in 1909/1910 and advanced to one of the poet's most important disciples in the 1920s. As early as 1909 he had submitted a fundamental programmatic writing with Herrschaft und Dienst, a little later he was entrusted with the editing of the yearbook for the spiritual movement together with Friedrich Gundolf and promoted the project of a common world view of the George Circle. On his main work Stefan George and the sheets for art. German intellectual history since 1890 (published 1929), a monumental history of the district, he worked since 1913. As a historian, Wolters dealt with the French 18th century and received an extraordinary professorship at the University of Marburg , then in 1923 a full professorship in Kiel . Both as a university professor and as the editor of the five-volume reading book Der Deutsche, he made a special effort to have an impact on the young people he wanted to educate in the George and national sense. In addition, Wolters translated Christian poems from Latin , Greek and Middle High German and wrote poems himself, which were published in George's sheets for art and in his own volumes of poetry. In the 1920s he also emerged as a national speaker.

life and work

Career

Wolters, born in 1876 as the son of the businessman Friedrich Wolters, grew up in the Catholic Rhineland and attended the secondary school in Rheydt from 1889 . He passed his Abitur in 1898 at the Gymnasium in Munich-Gladbach , which he attended since 1891. In the summer of the same year Wolters began studying history, linguistics and philosophy at the University of Freiburg im Breisgau , but after one semester he moved to Munich . From 1899 he studied history, economics and German at the Friedrich-Wilhelms-Universität zu Berlin . His main academic teachers were Kurt Breysig and Gustav von Schmoller . In the summer of 1900 and again in the winter of 1901 he went to Paris, where he attended lectures at the Sorbonne and did research in the national library on the (pre-) history of the French Revolution .

Wolters received his doctorate in October 1903 from Gustav Schmoller with studies on land ownership in France before the revolution. Allegedly Schmoller said that Wolters' doctoral thesis was the "most beautiful dissertation [he] ever had". He then edited the files on the history of Prussia under Elector Friedrich Wilhelm together with Breysig as part of Acta Borussica published by Schmoller . In 1905 he published an expanded version of his dissertation and then edited, again for Schmollers Acta Borussica , the history of the central administration of the army and taxes, especially in the Kurmark . In connection with this work he wrote an essay on the theoretical foundation of absolutism in the 17th century for a commemorative publication for the 70th birthday of his teacher Schmoller .

In 1907/1908 Wolters was the private tutor of Prince August Wilhelm of Prussia , whom he mainly taught history. Since the son of Kaiser Wilhelm II was just getting his doctorate, but had no talent for scientific work, Wolters wrote his dissertation mostly himself. The muddle was supported by Gustav Schmoller, whose research assistant Wolters was at the time. The doctorate on the development of the commissariat authorities in Brandenburg-Prussen was accepted in July 1908 with summa cum laude, ie with the highest distinction. Wolters received a few hundred Reichsmarks and the Order of the Crown, 4th class. He then earned his living as a teacher: he taught history, German and art history at girls' and women's schools. At the same time, he continued to work in the Schmoller's Commission on the History of Prussia, so that in 1913 he was able to submit his habilitation thesis on The History of the Central Administration of the Army and Taxes in Brandenburg-Prussia 1630–1697 .

At the turn of the century, Wolters belonged to an intellectual group that gathered around the universal historian Kurt Breysig in Niederschönhausen near Berlin. In Niederschönhausen he lived in a shared apartment with his friends Friedrich Andreae and Rudolf von Heckel, who together with Berthold and Diana Vallentin , Kurt Hildebrandt , Wilhelm Andreae and others formed the circle around Breysig. In June 1907, Wolters' shared flat (now with Berthold Vallentin and the Andreae brothers) and with it the district moved from the northeast to the southwest of Berlin, to Lichterfelde . Here also met Carl Petersen , the sculptor Ludwig Thormaehlen and the architect Paul Thiersch added; Wolters also met Erika Schwartzkopff here , whom he married in 1915. Historical, philosophical and literary questions were discussed, poems read and parties held.

Through the Breysig circle, Wolters came into contact with important poets of his time. In 1904 the playwright Georg Kaiser came to visit, in November 1905 Rudolf Borchardt stayed for two weeks with Wolters and Vallentin in Niederschönhausen. Wolters made a strong impression on Borchardt, who considered him “light, chivalrous, quick and agile”, “the mischief in the flashing, almost all-too-blue eyes, perfectly poetic without being a poet […]. He had the Charis and seemed to have the genius, he was a full picture of the most beautiful German and the most beautiful of youth's own virtues ”. Years later, Borchardt remarked that Wolters was "immediately convincing as a person and immediately appealing". In summary, he characterized him as a "manic enthusiast".

Rule and service and admission to the George circle

Shortly afterwards, Stefan visited George Breysig's group in Niederschönhausen. Wolters was deeply impressed by the famous poet. He had already met him in 1904 through Breysig and Vallentin, and now he tried harder to get closer to George. Initially, however, he was hardly interested. Wolters had not, as usual, joined George as a teenager; moreover, George probably disliked the unbridled pathos of his Niederschönhausen group. Wolters did not give up and made contact with the artist Melchior Lechter , a friend and colleague of Georges, on whom he later wrote a small monograph.

In 1908/1909 he finally managed to attract the poet's attention. Wolters wrote a pamphlet entitled Herrschaft und Dienst , in which George, who gathered a devoted circle around him, was particularly interested. The work, which was based on his work on the theory of absolutism , was published in excerpts in the eighth episode of George's magazine Blätter für die Kunst in February 1909 and a little later as a full edition furnished by Melchior Lechter. In this programmatic paper, Wolters outlines a comprehensive model of society. It is no coincidence that he uses the image of a circle that has its center in a “ruler” who, although not explicitly named, is indirectly identified as Stefan George through quotations from poems. Wolters draws concentric circles of people around this “ruler”: closest to him are a group of “feelers of the spirit” - probably identified as the members of the George circle - who directly receive the “light from the living center” and the “ruler “To serve with reverence, reverence and self-giving. The naturally given hierarchy finds its lowest-ranking members in the "coarse-groping" of the "outer courts", which are probably to be equated with the contemporary society - generally feuded by George.

In the spring of 1909 George stayed with Wolters in Berlin for a few weeks, a meeting that marked the breakthrough in their relationship - both for George, who was now beginning to appreciate Wolters, and to an even greater extent for Wolters. His friend Kurt Hildebrandt later said that Wolters had experienced a “fulfillment with the poet's world of thought” at this meeting. In March 1910 he finally met the "master" in the apartment of his friend Karl Wolfskehl in Munich, where George received him in the "Kugelzimmer" (circle designation). The poet introduced him to the Maximin myth, the story of a boy whom he had raised posthumously to god. Wolters was "speechless shaken" and "deeply moved", as George wrote in the Stern des Bund .

With his first circle essay Wolters had already presented one of the most important texts of the George Circle that was being constituted . Rule and service sealed the change from a circle of friends with common aesthetic convictions to a "state" with its own worldview, soon to be called " secret Germany ". Robert Boehringer noted in retrospect: "from his [Wolters'] way of thinking, the Platonic designation of the Circle of Friends as' The State 'came into use" (cf. Plato's Politeia ), Ernst Morwitz later got excited that all the misfortunes in the circle had started with it , "That Wolters invented this stupid 'state'".

However, Wolters' concept, despite its influence, was not undisputed. Friedrich Gundolf , George's first and for a long time most important disciple, wrote a treatise for the same edition of Blätter für die Kunst in which Wolters' essay appeared, entitled Followers and Disciples , in which he devised an alternative concept. The ideas of the two differed in both the role assigned to George for the disciples and the role assigned to the circle in society. For Gundolf, George embodied an idea that went beyond himself - the disciple subordinated himself to this idea and only for that reason to the master, whom he adored and loved as a mediator of the ideal. For Wolters , George was this world of ideas; the members of the circle had to revere him as a person. For Gundolf the circle was a haven of higher education within society, an elite - Wolters, on the other hand, tended to believe that the movement should encompass society as a whole. Even with the personality of the "manic enthusiast" Gundolf could not do much at first. In a letter he remarked about Wolters: "Pathos alone is not enough, one also has to have irony (romantic!)". In his followers and disciples , Gundolf also vehemently criticized those whom he called “priests” and whose reverence for the “master” he considered false and inauthentic - a criticism which, however, he only referred directly to Wolters much later.

The yearbook for spiritual movement

George could use the propagandist Wolters at a time when he was hoping for a broader public image, especially among German youth. For this purpose he had Gundolf publish his new magazine from 1910 to 1912, the yearbook for spiritual movement . The three volumes of the yearbook contained various articles by members of the district who were to constitute a common worldview and to present it to society, especially to the academic youth. Wolters made important contributions to this. For the first yearbook he wrote the treatise Guidelines , in which he divided the human mind into a "creative" and an "ordering" force. He understands the creative force as the creative force that gives off new “life”, while the organizing force only orders and dismantles and thus consumes life. Wolters therefore only accepts those works that have sprung from the creative force, that not only “order” their subject, but “create” anew by means of the three categories “deed”, “work” and “proclamation”. Following on from this, he developed the “gestalt” term in the next yearbook , which became formative for the scientific work of the circle in the period that followed. In the essay of the same name, Wolters designed the program of a “gestalt” biography, which should intuitively grasp the holistic unity of work and person of an artist and at the same time link it to “a fateful biographical plan to measure a successful life”. The concept was later implemented by Heinrich Friedemann and Friedrich Gundolf, for example, and the “Gestalt” biography became one of the most influential ideas in the history of ideas of the 1910s and 1920s.

In the treatise Human and Genus in the third yearbook , Wolters finally transferred his concepts to the “external state”, to society as a whole. In connection with an idealized image of Greek antiquity, the youth were called upon to ensure the renewal of society. This new society should reject the liberal ideas of equality and return to a hierarchical model of society: “Not general equality but natural difference should become human rights again, so that this delusion, which paralyzes our powers and makes our people a fearful merchant , should finally fall from the eyes , turns into a cowardly servant of humanity. ”The subordination to a charismatic leader was intended to eliminate the division of people into various interest groups with different convictions, which Wolters felt painfully.

Wolters' relationship with George developed difficult at first, as is clear from the correspondence in which George often briefly dispatches his disciple, probably primarily an indication that, although he considered Wolters to be useful, he did not develop a deeper personal relationship with him wanted or could. The main reason for this seems to have been the fact that Wolters lacked the homoerotic streak. This is probably why George referred to his disciple in a poem as the “first completely changed by the spirit”: Wolters came to him through intellect, not through eros. Wolters also noticed the distance: in one poem he described himself as George's “most distant you” and in a letter to the “master” he stated: “If I was 'a little late' at the beginning, that probably prevents me To be as close to your heart as I long for, but not to be as close to the front of the battle as I desire and I can ”.

Wolters wrote poetry his entire life, often addressing his admiration for George. His volumes of poetry, Wandel und Glaube (1911) and Der Wanderer (1924), were particularly important to him . Stefan George apparently valued Wolters' poems and published them in his Blätter für die Kunst . He had the volume Wandel und Glaube appear in his own publishing house. He even published a work by Wolters, the 1918/1919 poem Balduin , under his own name. It deals with the madness of his friend Baldwin von Waldhausen , who fell ill as a result of a war injury and whom Wolters had led to the circle and to George. His translations of Christian songs and hymns, however, met with little interest within the circle. George commented on a reading of the transmissions only ironically with the words: "That was a pious evening." Outside of the circle, Wolters was hardly noticed as a poet, he did not develop his own lyrical language.

The "Paul" of the George circle

Wolters soon had a permanent place in the “state” of Georges. He made an unconditional commitment to George. For each of his actions he asked for the permission of the "Master"; when he showed reluctance, he often dropped plans. Wolters displayed a religious transfiguration of George that was unusual even for a member of the district. His “master” was not just a loved and revered person for him, but the savior in person. Norbert von Hellingrath , also a member of the George Circle, soon referred to him - probably because of his sense of mission to the outside world - as " Paul ". Rudolf Borchardt, whom Wolters liked so much when they met, saw the disciple transformed by George "into the most hideous grimace of a grimaceous abomination religion".

Because some of George's older friends did not want to share his religiosity to the same extent, Wolters gathered his own circles to worship George - first in Berlin, later in Marburg and Kiel. However, some George friends increasingly distanced themselves. Ernst Morwitz and Robert Boehringer felt provoked by the dogmatic pathos in the Wolters circle's admiration for George, Boehringer even became almost violent at one point. Friedrich Gundolf sent a George admirer to Wolters in the 1920s with the words: "Since you have now decided to breathe in this air, I myself am not suitable for a 'church'".

After Wolters had submitted his habilitation thesis in June 1913 , he set about writing a story of Stefan George and the sheets for art . The George researcher Thomas Karlauf comments: “Wolters was perfect for the role of the George hagiograph. No one else thought so strictly hierarchically, no one pursued the idea of the circle of friends as a fighting community as rigorously as he did ”. On March 5, 1914, Wolters completed his habilitation under Gustav von Schmoller and was now a private lecturer at Berlin University. No sooner had he started his job than the First World War broke out, which was an important experience for Wolters. He was used as a driver and courier in France, Serbia, Macedonia and the Carpathian Mountains, but did not have to go through an immediate front-line experience. In letters to his homeland, he glorified the events of the war and spoke, for example, of the "spiritualization of the material battle ". Since spring 1917 he had to be treated for severe rheumatism in the joints, but came back to France in February 1918. In a book he later described in great detail the attack by the Central Powers on Serbia on the Danube in autumn 1915, in which he himself had participated.

In 1920 Wolters was finally appointed to an extraordinary professorship for middle and modern history at the Philipps University of Marburg . In Marburg he gathered talented young men whom he wanted to win over to the George Circle. He made an enormous impression on some young students. Max Kommerell, for example, wrote about his teacher that Wolters was a “true king and father of men”, a “strong wise and mild leader”. Via Wolters, Johann Anton , who obtained his doctorate in 1925 and, together with Kommerell, was one of the master's closest confidants in the 1920s, joined George in 1922. George, who was generally skeptical about Wolters' suggestions for the circle, rejected other Wolters students, but he often turned them down for himself. Walter Anton , Walter Elze , Ewald Volhard and Rudolf Fahrner also joined the wider George circle via Wolters . Wolters' students also included Hans-Georg Gadamer , Herman Schmalenbach , Wolfram von den Steinen , Fritz Cronheim , Roland Hampe , Adolf Reichwein and Georg Rohde .

Public agitation for nation and master

In the 1920s, Wolters' relationship with George intensified, who lived with him in Marburg for several weeks or months each year. In the winter semester of 1923/1924 Wolters was given a full professorship for Middle and Modern History at the University of Kiel . He owed the appointment to Carl Heinrich Becker , the State Secretary in the Prussian Ministry of Education, who used his position to promote members of the George Circle and worked in the background for Wolters' appointment. George has also visited him in Kiel every year since 1925. The poet's appreciation for his propagandist becomes tangible in a dedication poem that he wrote on Wolters after the war:

Let peoples break under

the pressure of fate. Vessels do not tremble at the most sudden jolt ..

Before the Lord, the domestic and foreign war applies.

Where there are such as you - there is victory.

With the increasing focus on his work for the circle - the recruiting of new disciples, the proclamation of the George Reich - Wolters increasingly turned his back on historical science, which he tended to reject anyway: After his habilitation there are only four publications that fall more or less into his real historical subject as an economic historian. Overall, his - often quite innovative and thoughtful - historical studies are methodically based on the specifications of Schmoller's Historical School of Economics , but also take up tendencies of the George circle. With Wolters philosophical ideas play a major role in the representation and explanation of historical facts. His tendency towards a historiography that admiringly places “great men” in the foreground also meets the theory and practice of Georgian science. For example, he contributed to a reassessment of the French statesman Colbert . As a professor in Kiel, he also acted as head of the historical seminar and as managing director of the Schleswig-Holstein University Society .

During the war, and especially with the German defeat, Wolters' nationalist views had intensified. George, who had a rather ambivalent attitude towards both war and the nation and wanted to avoid the lows of politics in general, was skeptical of his disciple's beliefs. In the 1920s, Wolters mainly published works in which he combined his nationalism with his interpretation of the George broadcast. On various occasions he gave national speeches, e.g. B. on the meaning of sacrificial death for the fatherland . 1925–1927 he published the " reading work " Der Deutsche , intended for secondary school students , in which he compiled texts from cultural history with the aim of giving the students a national, "holistic" education: based on the educational concept of the George Circle, the focus should not be on the "'scientific attitude to objectivity'", as Wolters called it, but on the formation of the whole person. Even during the Conservative Revolution , with which he shared some important convictions but was not personally connected, some of his works were not unknown.

The Treaty of Versailles he refused - as most Germans - vehemently. In 1923 he and his student Walter Elze published the anthology Voices of the Rhine , which was supposed to revive the national myth of the German Rhine . In a speech he had given on the occasion and which appeared in an expanded version as the introduction to the volume, he directed himself sharply against the French occupation of the Rhineland and Ruhr . He castigated the “unrestrained vengeance” of the French, whom he accused of having paid German “love for five hundred years with murder and fire”, and also included the racist accusation of “ black shame ”: “it [di France] has committed incest, mixed its blood with the juice of black and brown foreign peoples, absorbed the poison of African embers, incited slaves of foreign origin against free blood-related peoples and at this price tied the last sham victory to its tainted flag ”. Overall, his political position can be classified between the German National People's Party and the right wing of the German People's Party . In 1924 Wolters even took part in a völkisch memorial service for Albert Leo Schlageter , who was venerated as a martyr in right-wing circles , for which some members of the district criticized him. Even Julius countryman , friend in his time at Kiel well with Wolters, rejected certain traits such as his nationalism decisively.

At the beginning of November 1929, Wolters' monumental work Stefan George and the sheets for art finally appeared . German intellectual history since 1890 in Georg Bondi Verlag . On more than 600 pages he described the life story of George, who had closely accompanied the creation of the book, his work and the circle. The book initially presented the life and work of George on the basis of the individual editions of the sheets for art and positioned George once again in and above all against his time. Wolters emphasizes above all the religious and national dimension that he believed to be found in George's work and person. The positive reactions of many of George's friends and admirers also mixed extremely critical voices: Franz Blei described the work in cross-section as “a two-pound memorial inscription on a pseudo-lived object”. Even among some of Georges' acquaintances and friends, the “story of the leaves”, as it was mostly called there, caused astonishment. Max Kommerell cites the book as one of the main reasons for his apostasy from George; Friedrich Gundolf, whose estrangement from George was already over, was annoyed by "the hopelessly bad, thoroughly mendacious book". The anti-Semitic undertones also led to resentment among Jewish members of the circle such as Ernst Gundolf and Karl Wolfskehl, one of George's oldest friends.

After the early death of his first wife Erika in 1925, Friedrich Wolters married Gemma Thiersch in 1927 , the daughter of his friend Paul Thiersch. Wolters, who had been suffering from heart problems since the war, was hospitalized in Munich in March 1930 with the diagnosis of a " coronary thrombosis ". After initially improving, he died on April 14, 1930. He was buried in the forest cemetery in Munich. Stefan George, for whom Wolters had not only become particularly important as a propagandist in recent years, even planned to publish a Wolters memorial book. In 1931 his friends Julius Landmann and Carl Petersen founded the Friedrich Wolters Foundation, which, supported by funds from the Schleswig-Holstein University Society, awarded prizes for research on the history of ideas. After 1933, the foundation, under the leadership of Carl Petersen, came very close to National Socialism , whereupon Edith Landmann, a Jew , demanded its dissolution. In 1937 the foundation actually had to be dissolved when the university society withdrew its funds.

Fonts

A detailed bibliography can be found in the article by Friedrich Wolters on Wikisource .

Historical writings

- Studies on agricultural conditions and agricultural problems in France from 1700 to 1790 (= political and social science research , volume 22, issue 5). Duncker & Humblot, Leipzig 1905.

- with Kurt Breysig , Berthold Vallentin , Friedrich Andreae : Floor plans and building blocks for the theory of state and history. Compiled in honor of Gustav Schmoller and in memory of June 24, 1908, his seventieth birthday . Georg Bondi, Berlin 1908 ( digitized ).

- History of Brandenburg's finances from 1640–1697. Presentation and files (= documents and files on the history of the internal politics of Elector Friedrich Wilhelm von Brandenburg , 1st part). Volume 2: The Central Administration of the Army and Taxes . Duncker & Humblot, Munich / Leipzig 1915 (habilitation thesis; digitized version ).

Literary

- with Friedrich Andreae: Arcadian moods . S. Calvary, Berlin 1908 ( Verlaine translations and my own; digitized ).

- Change and Faith . Verlag der Blätter für die Kunst, Berlin 1911 ( digitized version ).

- The Wanderer. Twelve conversations . Georg Bondi, Berlin 1924 ( digitized version ).

- Fairy tales and stories of our soul . Printed by the workshops of the city of Halle in Burg Giebichenstein, Halle in 1926 ( digitized version ).

George Circle

- Rule and service (= Opus 1 of the unicorn press). Verlag der Blätter für die Kunst, Berlin 1909 (2nd edition Georg Bondi, Berlin 1920; 3rd edition 1923: digitized version ).

- Melchior Lechter . Hanfstaengel, Munich 1911 ( digitized version ).

- Stefan George and the leaves for art. German intellectual history since 1890 . Georg Bondi, Berlin 1930 ( digitized version ).

National

- with Carl Petersen : The heroic sagas of the early Germanic times . 2nd Edition. Ferdinand Hirt , Breslau 1922 ( digitized version ).

- with Walter Elze : Voices of the Rhine. A reading book for the Germans . Ferdinand Hirt, Breslau 1923.

- The Danube crossing and the invasion of Serbia by the IV Reserve Corps in autumn 1915 . Ferdinand Hirt, Breslau 1925.

- The German. A reading book . 5 volumes, Ferdinand Hirt, Breslau 1925–1927.

- Four speeches about the fatherland . Ferdinand Hirt, Breslau 1927 ( digitized version ).

Transfers

- Minnesongs and sayings. Transmissions from German minstrels of the XII. – XIV. Century . Verlag der Blätter für die Kunst, Berlin 1909 (2nd edition, Berlin 1922 as volume 3 of the hymns and songs of the Christian era ; digitized version ).

- Hymns and sequences from the Latin poets of the IV. To XV. Century . Verlag der Blätter für die Kunst, Berlin 1914 (2nd edition, Berlin 1922 as Volume 2 of the hymns and songs of the Christian era ; digitized version ).

- Songs of praise and psalms. Transmissions by the Greek-Catholic poets of the 1st to 5th centuries (= hymns and songs of the Christian era , volume 1). Verlag der Blätter für die Kunst, Berlin 1923 ( digitized version ).

swell

Friedrich Wolters' estate is in the Stefan George Archive , Stuttgart. Published documents:

- Michael Landmann : Friedrich Wolters. 1876-1930 . In: Michael Landmann: Figures around George . Volume 2, Castrum Peregrini Presse, Amsterdam 1988, ISBN 90-6034-067-1 , pp. 23-36 (report by Julius Landmann's son, which primarily illuminates Wolters' personality).

- Friedrich Wolters: Early notes after conversations with Stefan George on the "story of the pages" . Edited by Michael Philipp. In: Castrum Peregrini 225, 1996, pp. 5-61 ( digitized version ).

Correspondence

- Stefan George, Friedrich Wolters: Correspondence 1904–1930 (= Castrum Peregrini 233–235). Edited by Michael Philipp. Castrum Peregrini Presse, Amsterdam 1998 ( digitized ).

- Friedrich Gundolf - Friedrich Wolters: An exchange of letters from the circle around Stefan George . Edited by Christophe Fricker . Böhlau, Cologne / Weimar / Vienna 2009, ISBN 978-3-412-20299-6 .

Wolters is also described in the numerous memoirs of the circle members. The respective personal and intellectual position of the author towards Wolters and his works must be taken into account. The key to evaluating Wolters is always George's position towards him, which is presented in different ways. The first commemorative volume published after the war comes from Edgar Salin , a friend of Gundolf, who portrays Wolters rather negatively and emphasizes George's skepticism towards Wolters and his works. Kurt Hildebrandt, friend and pupil of Wolters, protected him against attacks in 1965 and collected evidence that George held Wolters in high esteem and played an active part in the works that Salin had criticized. Robert Boehringer, who was rather distant about Wolters' work personally, nevertheless endeavored to produce a balanced report.

literature

- Carola Groppe : The power of education. The German bourgeoisie and the George Circle 1890–1933 . Böhlau, Cologne / Weimar / Vienna 1997, ISBN 3-412-03397-9 , in particular pp. 213-289.

- Thomas Karlauf : Stefan George. The discovery of the charism . Blessing, Munich 2007, ISBN 978-3-89667-151-6 .

- Michael Philipp: Introduction . In: Stefan George, Friedrich Wolters: Correspondence 1904–1930 . Edited by Michael Philipp. Castrum Peregrini Presse, Amsterdam 1998, pp. 1-61.

- Michael Philipp: Change and Faith. Friedrich Wolters - The Paulus of the George circle . In: Wolfgang Braungart , Ute Oelmann, Bernhard Böschenstein (eds.): Stefan George: Work and effect since the 'Seventh Ring' . Niemeyer, Tübingen 2001, ISBN 3-484-10834-7 , pp. 283-299.

- Bastian Schlueter: Friedrich Wolters . In: Achim Aurnhammer, Wolfgang Braungart, Stefan Breuer , Ute Oelmann (eds.): Stefan George and his circle. A manual . Volume 3, de Gruyter, Berlin / New York 2012, pp. 1774–1779.

- Wolfgang Christian Schneider: State and Circle, Service and Faith. Friedrich Wolters and Robert Boehringer in their ideas about society . In: Roman Köster, Werner Plumpe , Bertram Schefold , Korinna Schönhärl (eds.): The ideal of the beautiful life and the reality of the Weimar Republic. Concepts of state and community in the George circle . Akademie Verlag, Berlin 2009, ISBN 978-3-05-004577-1 , pp. 97-122.

Web links

- Literature by and about Friedrich Wolters in the catalog of the German National Library

Remarks

- ↑ a b c Rudolf Borchardt, note on Stefan George [around 1936], edited from the estate and explained by Ernst Osterkamp, Munich 1998, p. 38.

- ↑ This aspect is mainly worked out by Carola Groppe, Die Macht der Bildung , pp. 213–289.

- ↑ See Fritz Wolters, Studies on Agricultural Conditions and Agricultural Problems in France 1700–1790 , Duncker & Humblot, Berlin 1905, unpaginated foreword.

- ^ Later published as the first chapter in Fritz Wolters, Studies on Agricultural Conditions and Agricultural Problems in France 1700–1790 , Duncker & Humblot, Berlin 1905, pp. 1–37.

- ↑ So at least Rudolf Borchardt, note on Stefan George [around 1936], edited from the estate and explained by Ernst Osterkamp , Munich 1998, p. 39.

- ↑ Friedrich Wolters, On the theoretical justification of absolutism in the 17th century , in: Kurt Breysig, Fritz Wolters, Berthold Vallentin, Friedrich Andreae, Grundrisse und Bausteine zur Staats- und Geschichtelehre. Compiled in honor of Gustav Schmoller and in memory of June 24, 1908, his seventieth birthday , Berlin 1908, pp. 201–222. For his career as a historian, cf. Groppe, The Power of Education , pp. 213f. (according to the documents of the Friedrich-Wilhelms-Universität).

- ↑ Cf. Lothar Machtan , A Doctor for the Prince , in: Die Zeit , No. 44, October 22, 2009; Karlauf, Stefan George , p. 450 with note 73 (p. 725f.).

- ^ In addition, Carola Groppe, Education, Profession and Science: Erika Schwartzkopff, m. Wolters , in: Ute Oelmann, Ulrich Raulff (eds.), Women around Stefan George , Wallstein, Göttingen 2010, pp. 171–193, here p. 178.

- ↑ Schneider, Staat und Kreis, Dienst und Glaube , p. 100. Kaiser had attended the same Magdeburg school as Hildebrandt and the Andreae brothers, through which the contact may have come about.

- ^ Rudolf Borchardt, Pseudognostische Geschichtsschreibung [1930], in: Rudolf Borchardt, Prosa IV , Klett-Cotta, Stuttgart 1996, pp. 292–298, citations p. 293.

- ↑ See Vallentin's letter to Wolters of October 7, 1904: George, Wolters, Briefwechsel , No. 1, p. 62. On this Philipp, Introduction , p. 5.

- ↑ On the meaning of the circle figure Schneider, Staat und Kreis, Dienst und Glaube , p. 109.

- ^ Friedrich Wolters, Herrschaft und Dienst , Verlag der Blätter für die Kunst, Berlin 1909. A more recent partial reprint in: Georg Peter Landmann (ed.), Der George-Kreis. A selection from his writings , Klett-Cotta, Stuttgart 1980, pp. 82–86. To get closer to George Karlauf, Stefan George , pp. 434–437. A concise summary and interpretation of the work is provided by Schneider, Staat und Kreis, Dienst und Glaube , pp. 104–107, quotations p. 105.

- ↑ Kurt Hildebrandt, Das Werk Stefan Georges , Hamburg 1960, pp. 334f. See on the meeting Philipp, Wandel und Glaube , p. 285f. and Philipp, Introduction , p. 6f.

- ↑ Stefan George, Da zur Begehung an des Freundes arm , in: Stefan George, Der Stern des Bundes [1913], edited by Ute Oelmann, Klett-Cotta, Stuttgart 1993 ( Complete Works in 18 Volumes , Volume 8), p. 88 Ernst Morwitz, Commentary on the work Stefan Georges , 2nd edition, Düsseldorf / Munich 1969, p. 384, and Kurt Hildebrandt, Das Werk Stefan Georges , Hamburg 1960, p. 384 connect the lines with Wolters. To the meeting in the “Kugelzimmer” Philipp, Wandel und Glaube , pp. 286–288; Philipp, Introduction , pp. 7-10.

- ↑ On the importance of rule and service for the formation of a circle, for example Schneider, Staat und Kreis, Dienst und Glaube , pp. 102-104, 115; Groppe, The Power of Education , p. 245.

- ^ Robert Boehringer, My picture by Stefan George. Text volume , 2nd edition, Düsseldorf / Munich 1967, p. 129.

- ↑ Ernst Morwitz in conversation with Fine von Kahler , February 1937 (based on the recordings of Fine von Kahler's conversation), here quoted from Ulrich Raulff, Kreis ohne Meister. Stefan Georges Nachleben , CH Beck, Munich 2009, p. 293.

- ^ Friedrich Gundolf, Gefolgschaft und Jüngertum , in: Blätter für die Kunst , 8th part, 1908/1909, pp. 106–112 (reprint in: Georg Peter Landmann (ed.), Der George-Kreis. A selection from his writings , Klett-Cotta, Stuttgart 1980, pp. 78-81).

- ↑ On this, Carola Groppe, Competitive Weltanschauungsmodelle in the context of the development of the circle and the external impact of the George Circle: Friedrich Gundolf - Friedrich Wolters , in: Wolfgang Braungart , Ute Oelmann, Bernhard Böschenstein (ed.), Stefan George: Work and effect since the Seventh Ring ' , Niemeyer, Tübingen 2001, pp. 265-282, here pp. 271-276; Groppe, Die Macht der Bildung , pp. 243–245.

- ^ Friedrich Gundolf to Ernst Morwitz on December 9, 1907, printed in: Stefan George, Friedrich Gundolf, Briefwechsel , edited by Robert Boehringer with Georg Peter Landmann, Munich / Düsseldorf 1962, p. 185. Quoted in Karlauf, Stefan George , p. 435. Similarly Edgar Salin, To Stefan George. Remembrance and Testimony , 2nd edition, Helmut Küpper formerly Georg Bondi, Munich / Düsseldorf 1954, p. 139, who in Wolters missed Georges' irony, especially in dealing with younger people (see Philipp, Introduction , p. 39). See also Groppe, Die Macht der Bildung , pp. 227f.

- ↑ See Philipp, Wandel und Glaube , pp. 296f.

- ↑ Friedrich Wolters, guidelines , in: Yearbook for Spiritual Movement , Volume 1, Berlin 1910, pp. 128–145 ( digitized version ). Summary, interpretation and criticism in Groppe, Die Macht der Bildung , pp. 236–240.

- ^ Friedrich Wolters, Gestalt , in: Yearbook for Spiritual Movement , Volume 2, Berlin 1911, pp. 137–158. On this, Carola Groppe, Competing Weltanschauung models in the context of the development of the circle and the external impact of the George Circle: Friedrich Gundolf - Friedrich Wolters , in: Wolfgang Braungart, Ute Oelmann, Bernhard Böschenstein (ed.), Stefan George: Work and effect since the 'Seventh Ring' , Niemeyer, Tübingen 2001, pp. 265–282, here pp. 269f. with note 13, quotation p. 270. On the “Gestalt” biography, which is particularly evident in Heinrich Friedemann's Plato. His Gestalt (Berlin 1914) and Gundolfs Goethe (Berlin 1916) emerge, general Ralf Klausnitzer, history of problems and ideas, “Gestalt” -biography and form analysis , in: LiGo. Basic literary terms online , November 25, 2007.

- ↑ Friedrich Wolters, Mensch und Gattung , in: Yearbook for Spiritual Movement , Volume 3, Berlin 1912, pp. 138–154, quotation p. 148 ( digitized version ). See Groppe, Die Macht der Bildung , pp. 247–251.

- ^ Stefan George, Friedrich Wolters, Correspondence 1904–1930 , Amsterdam 1998. Cf. for example Kai Köhler, Herrschaft und Dienst. The correspondence between Stefan George and Friedrich Wolters , on: literaturkritik.de , No. 11, November 2004, which summarizes: "Over long distances, the correspondence is a Wolters monologue"; Jens Bisky , Willing Self-Surrender in Pose and Jargon , in: Berliner Zeitung , December 24, 1998, speaks of the "condescension with which George treated his 'court historian'". It should also be noted, however, that George was never a diligent letter writer and that similar imbalances can also be found in other correspondence, cf. also Groppe, Die Macht der Bildung , pp. 283–286.

- ↑ Stefan George, As after the blessed awakening , in: Stefan George, Der Stern des Bundes [1913], edited by Ute Oelmann, Klett-Cotta, Stuttgart 1993 ( Complete Works in 18 Volumes , Volume 8), p. 104. Kurt Hildebrandt, Das Werk Stefan Georges , Hamburg 1960, pp. 334f., 388f. was the first to connect this position with Wolters, including Karlauf, Stefan George , p. 451f .; Philipp, introduction , p. 7.

- ↑ He enclosed the poem Gottesstreiter in a letter to George dated March 12, 1910, cf. George, Wolters, Briefwechsel , No. 32, pp. 76–79, here p. 79.

- ↑ Wolters to George, March 10, 1914, in: George, Wolters, Briefwechsel , No. 62, p. 99.

- ↑ This is the second, longer Balduin poem (in: Stefan George, Das neue Reich [1928], edited by Ute Oelmann, Klett-Cotta, Stuttgart 2001 ( Complete Works in 18 Volumes , Volume 9), p. 93 , brief comment on this p. 171). Already in Blätter für die Kunst , 11./12. Episode, 1919, p. 17, the poem can be found among the poems by George - although published anonymously here. His appreciation for the poems after Philipp, Introduction , p. 42. The attribution of the poem to Wolters comes from Ernst Morwitz, Commentary on the work by Stefan Georges , 2nd edition, Munich / Düsseldorf 1960, p. 473.

- ↑ On Waldhausen and the poem cf. Lothar Helbing , Claus Victor Bock , Stefan George. Documents of its effect , Castrum Peregrini Presse, Amsterdam 1974, pp. 274-276.

- ↑ Edith Landmann, Conversations with Stefan George , Düsseldorf / Munich 1963, p. 112, on this Philipp, introduction , p. 42.

- ^ Philipp, Introduction , p. 54.

- ↑ See Philipp, Introduction , p. 23f.

- ↑ See for example Philipp, Wandel und Glaube , pp. 288–291.

- ↑ Passed on by Edgar Salin, To Stefan George. Remembrance and Testimony , 2nd edition, Munich / Düsseldorf 1954, p. 105. Boehringer also mentions the “Pauline von Wolters” (Robert Boehringer, Mein Bild von Stefan George. Textband , 2nd edition, Munich / Düsseldorf 1967, p. 140 ). See Philipp, Wandel und Glaube , p. 294f.

- ↑ Stefan Breuer , Aesthetic Fundamentalism. Stefan George and German Antimodernism , Wissenschaftliche Buchgesellschaft, Darmstadt 1995, p. 80 even describes Wolters as a “tribal chief” with his own “duchy”.

- ↑ See Karlauf, Stefan George , p. 452; Philipp, Wandel und Glaube , pp. 295–297.

- ↑ It was about Rudolf Fahrner, who reported this himself, cf. Rudolf Fahrner, Rudolf Fahrner on Wolters , in: Robert Boehringer, Mein Bild von Stefan George. Text volume , 2nd edition, Munich / Düsseldorf 1967, pp. 252–254, here p. 252.

- ^ Karlauf, Stefan George , p. 451.

- ↑ Cf. Reinhard Tenberg, Wolters, Friedrich , in: Walther Killy (Ed.), Literatur-Lexikon. Authors and works in the German language , Volume 12, 1988–1992, pp. 57f .; Walther Killy, Wolters, Friedrich , in: Walther Killy (Hrsg.), Deutsche Biographische Enzyklopädie , Volume 10, 1999, p. 59. Anders Wolfgang Weber , Biographical Lexicon of History in Germany, Austria and Switzerland. The chair holders from the beginnings of the subject until 1970 , 2nd edition, Lang, Frankfurt am Main et al. 1987, p. 55, who probably incorrectly names Breysig as supervisor.

- ↑ To Stefan George, Feldpost Juni 1918, in: George, Wolters, Briefwechsel , No. 100, p. 141f., Quotation p. 142.

- ↑ On Wolters' war experience, Philipp, Introduction , pp. 25–29.

- ↑ Friedrich Wolters, The Danube Crossing and the Burglary of Serbia by the IV Reserve Corps in Autumn 1915 , Ferdinand Hirt, Breslau 1925. On this Christophe Fricker, Introduction , in: Friedrich Gundolf - Friedrich Wolters , pp. 7–53, here p. 25 -27.

- ^ Note, Marburg, November 10, 1921, in: Max Kommerell, Letters and Records. 1919–1944 , edited by Inge Jens , Olten / Freiburg 1967, pp. 105f. Quoted from Landmann, Friedrich Wolters , p. 23.

- ↑ See Karlauf, Stefan George , p. 531; Philipp, introduction , p. 39f.

- ↑ Gadamer reports on an economic history lecture by Wolters, in which he "presented very sober things with a somewhat inappropriate rhetorical pathos without convincing suggestion" ( Stefan George (1868–1933) , in: Hans-Joachim Zimmermann (ed.), Die Effect of Stefan Georges on science. A symposium , Carl Winter Universitätsverlag, Heidelberg 1985, pp. 39–49, here p. 41), but noted on another occasion “how much he owed Wolters” (Bertram Schefold, Politische Ökonomie as “humanities.” Edgar Salin and other economists around Stefan George , in: Harald Hagemann (ed.), Studies on the Development of Economic Theory XXVI (= writings of the Association for Socialpolitik, New Series , Volume 115/26), Duncker & Humblot , Berlin 2011, pp. 149-210, here p. 202).

- ↑ A more complete list can be found in Philipp, Introduction , p. 40.

- ↑ See Groppe, Die Macht der Bildung , p. 557.

- ^ F. W :, in: Stefan George, Das neue Reich [1928], edited by Ute Oelmann, Klett-Cotta, Stuttgart 2001 ( Complete Works in 18 Volumes , Volume 9), p. 79.

- ↑ To Wolters' Relationship to Science Philipp, Introduction , pp. 33–36.

- ↑ Friedrich Wolters, Colbert , in: Erich Marcks , Karl Alexander von Müller (ed.), Meister der Politik. A world historical series of portraits , Volume 2, Deutsche Verlagsanstalt, Stuttgart / Berlin 1922, pp. 1–38. On Wolters' achievements and his classification as an economic historian, cf. Bertram Schefold, Political Economy as “Spiritual Science”. Edgar Salin and other economists around Stefan George , in: Harald Hagemann (ed.), Studies on the Development of Economic Theory XXVI (= Writings of the Association for Socialpolitik, New Series , Volume 115/26), Duncker & Humblot, Berlin 2011, p 149-210, here pp. 169-172.

- ^ Philipp, introduction , p. 59, note 41.

- ↑ Philipp, Introduction , pp. 29–33.

- ↑ These speeches - The meaning of sacrificial death for the fatherland , Goethe as an educator for patriotic thinking , Holderlin and the fatherland and The Rhine our fate (see below) - were published together in 1927: Friedrich Wolters, Four speeches about the fatherland , Ferdinand Hirt, Wroclaw 1927.

- ↑ See the reading work Groppe, Die Macht der Bildung , pp. 276–283. Quotation from an advance notice of the reading book, quoted from Groppe, Die Macht der Bildung , p. 281.

- ↑ See Groppe, Die Macht der Bildung , pp. 266–268.

- ↑ See Armin Mohler , Karlheinz Weißmann , The Conservative Revolution in Germany, 1918–1932. A manual , 6th edition, Ares Verlag, Graz 2005, pp. 488f.

- ↑ See e.g. B. Friedrich Wolters, The Conditions of the Versailles Treaty and their Justification. Speech for the memorial hour planned by the university on the day of the ten years of signing the Versailles Treaty , printed as a manuscript by Max Tandler, Kiel 1929 ( digitized ). In addition Bertram Schefold, Political Economy as “Spiritual Science”. Edgar Salin and other economists around Stefan George , in: Harald Hagemann (ed.), Studies on the Development of Economic Theory XXVI (= Writings of the Association for Socialpolitik, New Series , Volume 115/26), Duncker & Humblot, Berlin 2011, p 149-210, here p. 173f.

- ↑ Quotations from Der Rhein, our fate , in: Friedrich Wolters, Vier Reden über das Vaterland , Breslau 1927, pp. 99–170, here pp. 165–167. See Groppe's speech, Die Macht der Bildung , pp. 259–261; Michael Petrow, The Poet as Leader? On the effect of Stefan Georges in the “Third Reich” , Tectum Verlag, Marburg 1995, p. 15f.

- ^ Karlauf, Stefan George , p. 528.

- ^ Karlauf, Stefan George , p. 548.

- ↑ See the reports from Landmann's sons Michael and Georg Peter: Michael Landmann, Friedrich Wolters , p. 23; Georg Peter Landmann describes the friendship as "warm", cf. Georg Peter Landmann, comments by an eyewitness , in: Hans-Joachim Zimmermann (ed.), The effect of Stefan George on science. A symposium , Carl Winter Universitätsverlag, Heidelberg 1985, p. 95.

- ↑ This is particularly clear in the correspondence: Stefan George, Friedrich Wolters, Briefwechsel 1904–1930 , Amsterdam 1998. During George's frequent visits to Marburg and especially later in Kiel, the book was also worked on, cf. the report by Roland Hampes, Kieler Kollegen. Stefan George and Friedrich Wolters , in: Castrum Peregrini , Volume 143–144, 1980, pp. 43–49, here p. 43f.

- ↑ On this Steffen Martus , Werkpolitik. On the literary history of critical communication from the 17th to the 20th century with studies on Klopstock, Tieck, Goethe and George , de Gruyter, Berlin / New York 2007, pp. 671f., 683f. There pp. 666–685 a detailed discussion of the “history of the leaves”.

- ↑ Karlauf, Stefan George , with a detailed explanation of the work and the negative part of the effect (pp. 596–601).

- ^ Franz Blei, Stefan Georges Tempelglocken , in: Der Cross Section , 10, 9, 1930, p. 629. Quoted from Karlauf, Stefan George , p. 596.

- ↑ See Kommerell: Max Kommerell, Letters and Records. 1919–1944 , edited by Inge Jens, Olten / Freiburg 1967, pp. 171, 196 (letters to Stefan George of June 17, 1930 and to Johann Anton of December 7, 1930); Quote Gundolf in: Karl and Hanna Wolfskehl, correspondence with Friedrich Gundolf. 1899–1931 , edited by Karlhans Kluncker, Volume 2, Amsterdam 1977, p. 204 (letter to Karl Wolfskehl of June 17, 1930).

- ↑ Michael Philipp, “In politics things went differently”. The theme of the 'Jewish' in the George circle before and after 1933 , in: Gert Mattenklott , Michael Philipp, Julius H. Schoeps (eds.), “Misunderstood brothers”? Stefan George and the German-Jewish bourgeoisie between the turn of the century and emigration , Georg Olms Verlag, Hildesheim / Zurich / New York 2001, pp. 31–53, here pp. 36f .; Michael Petrow, The Poet as Leader? On the effect of Stefan Georges in the “Third Reich” , Tectum Verlag, Marburg 1995, p. 16f.

- ↑ See letter from his wife Gemma Wolters to Stefan George dated March 9, 1930, in: George, Wolters, Briefwechsel , No. 254, pp. 248f., Here p. 249.

- ^ Berthold Vallentin, Conversations with Stefan George, 1902–1931 , Castrum Peregrini Presse, Amsterdam 1967, p. 136 (briefly on the funeral), 125 (on the memorial book).

- ↑ On the Landmann Foundation, Friedrich Wolters , pp. 33–35.

- ^ On the problem of Wolters reception in the Ulrich Raulff district , circle without a master. Stefan Georges Nachleben , CH Beck, Munich 2009, p. 369.

- ↑ Edgar Salin, To Stefan George. Memory and Testimony , Munich / Düsseldorf 1948.

- ↑ Kurt Hildebrandt, Memories of Stefan George and his circle , Bouvier, Bonn 1965.

- ^ Robert Boehringer, My picture by Stefan George. Text volume , 2nd edition, Düsseldorf / Munich 1967 (1st edition 1950).

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Wolters, Friedrich |

| ALTERNATIVE NAMES | Wolters, Friedrich Wilhelm; Wolters, Fritz (rare) |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | German historian, poet and translator |

| DATE OF BIRTH | September 2, 1876 |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | Uerdingen |

| DATE OF DEATH | April 14, 1930 |

| Place of death | Munich |