Melancholy (munch)

|

| melancholy |

|---|

| Edvard Munch , 1892 |

| Oil on canvas |

| 64 × 96 cm |

| Norwegian National Gallery , Oslo |

|

| melancholy |

|---|

| Edvard Munch , 1894 |

| Oil on canvas |

| 72 × 98 cm |

| Private collection |

|

| melancholy |

|---|

| Edvard Munch , 1894-96 |

| Oil on canvas |

| 81 × 100.5 cm |

| Art Museum, Bergen |

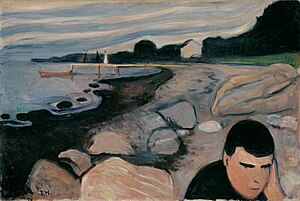

Melancholy ( Norwegian melankoli , also evening , jealousy , the yellow boat or Jappe am Strand ) is a motif by the Norwegian painter Edvard Munch , which he executed in five paintings between 1891 and 1896 and in two woodcuts in 1896 and 1902 . In the foreground it shows a man sitting on the beach with his head propped up, while in the background a couple is on their way to a boat trip. The colors support the melancholy mood of the scenery. In the motif, Munch processed the unhappy love affair between his friend Jappe Nilssen and the married Oda Krohg , which reflected his own past relationship with a woman who was also married. The melancholy figure in the foreground is therefore associated both with Munch's friend and with the painter himself. Melancholy is considered to be one of the first symbolist pictures by the Norwegian painter and is part of his life frieze .

Image description

Immediately at the front edge of the picture surface sits a slumped male figure on a stony beach. She leaned her head thoughtfully on her hand, a classic pose of melancholy . The version from 1892 differs from the other pictures in that the figure is completely pushed into the lower right corner. The averted head and the direction of the hand reinforce a movement out of the picture. This corner position repeatedly draws the viewer's attention back to the landscape, which thus becomes an equal part of the picture. In the upper part of the picture a footbridge can be seen on which there are three figures: a couple and a man with oar blades. You are on your way to a yellow boat at the end of the pier. The curved shoreline, which continues behind the jetty, creates an effect of depth . It corresponds to the tree and cloud formations in the background.

The first version of the painting from 1891 is a mixture of different painting techniques: pastel , oil and pencil . Parts of the canvas remained completely unpainted. According to Hans Dieter Huber, this gives the picture a dry, fresco-like effect. The later oil paintings also retained the two-dimensional forms with greatly simplified contours that are reminiscent of synthetism . There is no aerial perspective and there is no shading , only the head and hand of the figure show a three-dimensional plasticity. According to Tone Skedsmo and Guido Magnaguagno, the picture anticipates the style of Munch's future works in its broad brushwork and the “simplification and stylization of line, shape and color”.

Edvard Munch: Evening / Melancholy . Oil, pastel and pencil on canvas, 1891, 73 × 101 cm, Munch Museum Oslo

Edvard Munch: melancholy . Oil on canvas, 1893, 86 × 129 cm, Munch Museum Oslo

interpretation

Alf Bøe sees a “greater personal breakthrough” for Munch in melancholy . After individual earlier attempts such as The Sick Child or Night in Saint-Cloud , Munch found in this key work the psychologically intense painting style that had become characteristic of his symbolist works of the 1890s. According to Tone Skedsmo and Guido Magnaguagno, Munch's picture primarily expresses a mood. The painter's thoughts and emotions are immediately transferred to the canvas. Nature serves as the carrier of the mood. From the large, simplified forms to the curved rhythm of the coastline to the dull tone of the coloring , the composition is completely subject to the creation of a mood.

Hans Dieter Huber analyzes the effect of the colors from the “green-yellow haze of jealousy” to the “snake-like blue-violet” of the shoreline, which connects the melancholic with what is happening on the jetty and “to want to ensnare and capture” him seems. The yellow boat, which gave the picture one of its alternative titles, also has the color of jealousy , which Christian Krohg already emphasized: "Thank Munch that the boat is yellow - if it weren't for that, Munch would not have painted the picture." Shelley Wood Cordulack refers in particular to the unusual black color of the beach, which not only compositionally combines the black figure in the foreground with the silhouettes of the same color in the background and thus reveals the reason for the melancholy mood, but which is also an expression of sadness and melancholy in terms of color symbols .

Ann Temkin, the curator of MoMa , the suppleness of the beach line is reminiscent of both an internal world of imagination and an external landscape. For Arne Eggum , it symbolizes the loneliness and the feeling of emptiness of the melancholy figure in the foreground, whose vision conjures up the couple on the footbridge. Reinhold Heller also sees a projection of the jealous man in the couple. The tension between illusion and reality is reinforced by the pictorial means used, such as the contrast between spatial depth and planar forms. Munch himself described in a note around 1894/95: "Jealousy - a long, desolate bank". Ulf Küster reminds the action in the picture of Ibsen's drama Ghosts . As Helene Alving reports in the drama of “Ghosts” that the audience cannot see, the foreground figure in Munch's picture also seems to convey what is happening in the background to the viewer. With this, Munch transferred the dramatic technique of pondoscopy to painting.

Uwe M. Schneede sees the figure in the foreground as a mediator who breaks the unity of the picture. On the one hand, it symbolizes the artist himself and his isolation from what is happening; on the other hand, it speaks directly to the viewer and appeals to his sympathy. In contrast to the art of the early 19th century, the subject is no longer part of the event and forms the center of the picture, but is cut off and even turned away at the edge. The three figures on the footbridge belonged to a different world, they symbolized the classic topos of the departure to an island of love and are bathed in bright, promising colors. What remains is the lonely, self-reliant individual who is denied the happiness of others. Instead, he translates the conflicts between the inside and outside world into a creative process. Melancholy thus already shows the basic constellation of the following pictures Desperation and The Scream , in which the break between a first-person figure and its environment is carried out and this develops into a "landscape of death". A later modification of the motif , also called Despair , places the Jappe figure out of melancholy under the red-colored sky of the scream , an "additive composition" according to Heller that loses the intensity and effect of the earlier motifs.

Edvard Munch: Despair , 1892, 92 × 67 cm, Thielska galleriet , Stockholm

Edvard Munch: The Scream , 1893, 91 × 73.5 cm, Norwegian National Gallery , Oslo

Edvard Munch: Despair , 1894, 92 × 72.5 cm, Munch Museum Oslo

background

The motif of a melancholy figure in a landscape has a long tradition in art history that goes back to Geertgen tot Sint Jans ' Johannes in the desert and Albrecht Dürer's Melencolia I. Arne Eggum sees a relationship in particular to the etching Abend by Max Klinger , who was well known in Kristiania, and to Paul Gauguin's painting Christ on the Mount of Olives , in which, like Munch, a deputy figure expresses the painter's suffering. Reinhold Heller confirms the connection to a motivic tradition, but he turns against a concrete reference to Dürer or Gauguin, since Munch's style was fed less by art-historical models than by his own memory. In Munch's work, the figure sitting on the bank becomes a kind of symbol that has detached itself from the specific occasion in order to express a fundamental human feeling. The forerunners of the motif in Munch's work can be found in the thoughtful pose of the man at the night window in Saint-Cloud or the portrait of Sister Inger on the beach , where nature also mirrors human feelings. The beach - often in the evening - will remain characteristic of Munch's work. Matthias Arnold describes: "People stand alone or in pairs - but even then lonely - on the shore and look at the sea, this reflection of their soul."

Geertgen dead Sint Jans : Johannes in the desert , approx. 1490, 42 × 28 cm, Gemäldegalerie Berlin

Albrecht Dürer : Melencolia I , approx. 1514, 24 × 18.5 cm

Paul Gauguin : Christ on the Mount of Olives , 1889, 73 × 92 cm, Norton Museum of Art, West Palm Beach

Edvard Munch: Night in Saint-Cloud , 1890, 64.5 × 54 cm, Norwegian National Gallery , Oslo

Edvard Munch: Inger on the beach , 1889, 126 × 161 cm, Bergen Art Museum

The specific reason for the picture was the summer of 1891, which Munch traditionally spent in Åsgårdstrand , a small Norwegian coastal town on the Oslofjord , which served as a summer retreat for many citizens and artists from nearby Kristiania, today's Oslo . Munch's friend Jappe Nilssen and the painter couple Christian and Oda Krohg spent the summer in the same place, and Munch witnessed the unhappy love affair between the 21-year-old friend and the married woman ten years older. The relationship awakened Munch memories of his own unhappy love for Milly Thaulow, only a few years ago. Munch, too, was 21 years old when he fell in love with the three-year-old wife of his cousin Carl Thaulow (a brother of the painter Frits Thaulow ) in 1885 , a forbidden love that haunted him for a long time and which he wrote in a novel between 1890 and 1893 Records in which he gave his lover the name "Frau Heiberg" processed. At the end of the affair he announced: “After that I gave up all hope of being able to love.” According to Reinhold Heller, Jappe Nilssen made it possible for his friend Munch to relive his own experiences a second time and to give them artistic symbolism in the summer of 1891. The portrayed Jappe in a melancholy pose thus becomes an ambiguous figure of identification for the painter himself.

In a prose poem probably composed in the early 1890s , Munch describes the mood of the picture in his own words: “It was evening. I walked along the sea - moonlight between the clouds ”. A man walks by the side of a woman until he realizes that it is an illusion and the woman is far away. Suddenly he thinks he recognizes them on a long quay: "a man and a woman - they are now going out onto the long pier - to the yellow boat - and behind them a man with oars". The walk and the movements remind him of the woman who he knows is many miles away. "There they go down into the boat - she and he". They go to an island and the man imagines them walking arm in arm while he is left alone. "The boat is getting smaller and smaller - the strokes of the oars resound over the surface of the sea - I was alone - the waves glided up to him monotonously - and sloshed against stone - but out there - the island was smiling in the mild summer night".

Pictorial history

In the course of 1891 Munch created a large number of sketches on the motif of melancholy , in which he varied the position of the person in the foreground and the shoreline. What all the sketches had in common was a two-dimensional and silhouette-like character, which marked a change in style from the influence of neo-impressionism of the Parisian years to future synthetism and symbolism . For Reinhold Heller, the number of sketches proves the importance of the motif for Munch, but also his intense struggle for a new expression. For the autumn exhibition in Kristiania in 1891, Munch submitted three other works as well as a first version of Melancholie , at that time still under the title Evening . Mostly it is assumed that it is the pastel that is now in the Munch Museum in Oslo . Arne Eggum, on the other hand, suspects that the oil painting, dated 1894, from a private collection could have been completed and submitted for exhibition as early as 1891.

The reactions to Munch's new works were almost entirely negative. Erik Werenskiold accused Munch of "mostly leaving his things half-finished, smearing oil and pastel colors together and, regardless of the atmosphere, leaving huge areas of his canvas completely unpainted". Newspaper critics disparaged his pictures as "humoresque". Christian Krohg, of all people, who and his wife set the model for the couple on the jetty, heard the only positive voice: "It's an extremely moving picture, solemn and serious - almost religious". Krohg saw a great gap between the Norwegian tradition, which his own pictures obeyed, and Munch's works, which lacked any connection to their common predecessors. With his art, Munch addresses the mind of the beholder directly: “He is the only one who is committed to idealism and who dares to make nature, the model, etc. the bearer of his mood and thus to achieve more . - Has anyone heard such a sound of color as in this picture? "

Munch spent the winter of 1891/92 in Nice on a scholarship , but here too the impressions from Norway he had taken with him from the summer preoccupied him far more than the Mediterranean surroundings. The first preparatory work was done on the intense red sky of a sunset, which could later be seen in the scream . Most of the time, however, Munch struggled again with the evening / melancholy motif, from which he designed a vignette for the Danish poet Emanuel Goldstein. Probably in March 1892, before he returned to Norway, Munch created the painting version from 1892 based on the sketches for the vignette, which in 1959 passed into the possession of the Norwegian National Gallery from the estate of Charlotte and Christian Mustad , where it has been on view since 1970 . The first drafts showed the figure known from the other versions in profile before Munch painted it over and turned his head down out of the painting. It was not until June 1892 that Munch finally completed the work on the vignette, which had occupied him for six months.

From the first compilation of his works under the title Study for a series “Die Liebe” in 1893, melancholy was an integral part of the so-called frieze of life , a cycle of Munch's central works on the themes of life, love and death. In the years 1893, 1894 and 1894 to 1896 he created three further versions of the motif. Two woodcuts were made in 1896 and 1902. They become evening in the catalog raisonné of all of Munch's graphics by Gerd Woll . Called Melancholy I and Melancholy III . The two cuts are almost identical. However, only the 1902 version retains the direction of the painting, while the 1896 version is mirrored. Both woodcuts consist of two separate panels, which in turn have been cut up to allow different color applications. Munch experimented with various color combinations for the prints. Munch used the title Melancholie for two other motifs in his later works: the portrait of a crying woman on the beach (for example in the Reinhardt frieze , which is shown in the Neue Nationalgalerie in Berlin) and a portrait of his sister Laura, who was from her youth under depression suffered.

Edvard Munch: evening. Melancholy i . Woodcut, 1896, 41.1 × 55.7 cm, Munch Museum Oslo

Edvard Munch: Melancholy III . Woodcut, 1902, 38.7 × 47.8 cm, Thielska galleriet , Stockholm

Edvard Munch: Melancholy (Reinhardt-Fries) . 1906–07, 90 × 160 cm, Neue Nationalgalerie , Berlin

Edvard Munch: melancholy . 1911, 120 × 125 cm, Stenersen Museum , Oslo

literature

- Arne Eggum : The meaning of Munch's two stays in France in 1891 and 1892 . In: Sabine Schulze (Ed.): Munch in France . Schirn-Kunsthalle Frankfurt in collaboration with the Musée d'Orsay, Paris and the Munch Museet, Oslo. Hatje, Stuttgart 1992, ISBN 3-7757-0381-0 , pp. 123-125.

- Arne Eggum: melancholy . In: Edvard Munch. Love, fear, death . Kunsthalle Bielefeld, Bielefeld 1980, without ISBN, pp. 131–132.

- Reinhold Heller: Edvard Munch. Life and work . Prestel, Munich 1993. ISBN 3-7913-1301-0 , pp. 52-57.

- Uwe M. Schneede : Edvard Munch. The early masterpieces . Schirmer / Mosel, Munich 1988, ISBN 3-88814-277-6 , pp. 7-9.

- Tone Skedsmo, Guido Magnaguagno: Melancholy, 1891 . In: Edvard Munch . Museum Folkwang, Essen 1988, without ISBN, cat. 25.

Web links

- Melancholy, 1892 in the National Museum Oslo .

- Edvard Munch, Melancholy, a woodcut in the British Museum London.

- Melancholy III (Melankoli III) in the Museum of Modern Art New York.

- Melancholy III in the Gundersen private collection in 1902 .

Individual evidence

- ↑ Arne Eggum: The meaning of Munch's two stays in France in 1891 and 1892 , pp. 124–125.

- ↑ a b c Reinhold Heller: Edvard Munch. Life and work . Prestel, Munich 1993. ISBN 3-7913-1301-0 , pp. 52-53.

- ^ Matthias Arnold: Edvard Munch . Rowohlt, Reinbek 1986. ISBN 3-499-50351-4 , p. 44.

- ↑ Ulrich Wiesner: Munch's staging of symbolic constellations . In: Edvard Munch. Love, fear, death . Kunsthalle Bielefeld, Bielefeld 1980, without ISBN, p. 440.

- ↑ Reinhold Heller: Edvard Munch. Life and work . Prestel, Munich 1993. ISBN 3-7913-1301-0 , p. 53.

- ^ A b Hans Dieter Huber : Edvard Munch. Dance of life. Reclam, Stuttgart 2013, ISBN 978-3-15-010937-3 , pp. 48-49.

- ↑ a b Reinhold Heller: Edvard Munch. Life and work . Prestel, Munich 1993. ISBN 3-7913-1301-0 , pp. 53-54.

- ↑ a b c d e Tone Skedsmo, Guido Magnaguagno: Melancholie, 1891 . In: Edvard Munch . Museum Folkwang, Essen 1988, without ISBN, cat. 25.

- ^ Alf Bøe: Edvard Munch. Bongers, Recklinghausen 1989, ISBN 3-7647-0407-1 , p. 14.

- ^ Arne Eggum: Melancholy . In: Edvard Munch. Love, fear, death . Kunsthalle Bielefeld, Bielefeld 1980, without ISBN, p. 131.

- ↑ Shelley Wood Cordulack: Edvard Munch and the Physiology of Symbolism . Fairleigh Dickinson University Press, Madison 2002, ISBN 0-8386-3891-0 , pp. 81-82 ( via Questia ).

- ↑ Edvard Munch. Melancholy. 1891 at the Museum of Modern Art New York.

- ↑ a b Arne Eggum: The meaning of Munch's two stays in France in 1891 and 1892 , p. 124.

- ↑ Ulf Küster: Ghosts. Thoughts on the theatrical with Edvard Munch. In: Dieter Buchhart (ed.): Edvard Munch. Sign of modernity . Hatje Cantz, Ostfildern 2007, ISBN 978-3-7757-1912-4 , p. 33.

- ^ Uwe M. Schneede: Edvard Munch. The early masterpieces . Schirmer / Mosel, Munich 1988, ISBN 3-88814-277-6 , pp. 8-9.

- ↑ Reinhold Heller: Edvard Munch: "The Scream" . Penguin, London 1973, ISBN 0-7139-0276-0 , p. 95.

- ↑ Max Klinger: <On Death, I>: Night in the National Museum of Western Art Tokyo.

- ^ Matthias Arnold: Edvard Munch . Rowohlt, Reinbek 1986. ISBN 3-499-50351-4 , pp. 44-45.

- ^ Hans Dieter Huber: Edvard Munch. Dance of life . Reclam, Stuttgart 2013, ISBN 978-3-15-010937-3 , pp. 47-48.

- ^ Matthias Arnold: Edvard Munch . Rowohlt, Reinbek 1986. ISBN 3-499-50351-4 , pp. 32-33.

- ↑ a b Reinhold Heller: Edvard Munch. Life and work . Prestel, Munich 1993. ISBN 3-7913-1301-0 , p. 54.

- ↑ Quotations from: Arne Eggum: Melancholie . In: Edvard Munch. Love, fear, death . Kunsthalle Bielefeld, Bielefeld 1980, without ISBN, p. 132.

- ↑ Reinhold Heller: Edvard Munch. Life and work . Prestel, Munich 1993. ISBN 3-7913-1301-0 , pp. 52-53, 57.

- ↑ Reinhold Heller: Edvard Munch. Life and work . Prestel, Munich 1993. ISBN 3-7913-1301-0 , pp. 54-55, 57.

- ^ Melancholy, 1892 in the National Museum Oslo .

- ↑ Reinhold Heller: Edvard Munch. Life and work . Prestel, Munich 1993. ISBN 3-7913-1301-0 , p. 57.

- ^ Hans Dieter Huber: Edvard Munch. Dance of life . Reclam, Stuttgart 2013, ISBN 978-3-15-010937-3 , pp. 65-70.

- ^ Gerd Woll: The Complete Graphic Works . Orfeus, Oslo 2012, ISBN 978-82-93140-12-2 , pp. 123, 198.