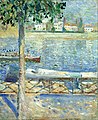

Night in Saint-Cloud

|

| Night in Saint-Cloud |

|---|

| Edvard Munch , 1890 |

| Oil on canvas |

| 64.5 × 54 cm |

| Norwegian National Gallery , Oslo |

Night in Saint-Cloud (Norwegian: Natt i Saint-Cloud ; often also Nacht in St. Cloud , Norwegian: Natt i St. Cloud ) is a painting by the Norwegian painter Edvard Munch . It was created in the French village of Saint-Cloud in 1890 and shows a man who looks out over the Seine at night from his room . The picture evokes a feeling of melancholy through its motif and color scheme . In Munch's work it plays a key role in the transition to symbolism .

Image description

A man in a top hat sits in his room by the window at night and looks out over a river. The high-contrast vertical and horizontal axes of the picture structure the space. They give the room an appearance of space, to which the figure, which is pushed to the edge and the curtain used as a repoussoir on the left edge of the picture, also contribute. The outlines of a table can be seen on the right. Dark blue and purple tones predominate in the room. Individual yellow, orange and reddish spots of color - with the exception of a smoldering cigarette - can only be seen outside. The full moon covers the couch and floor with a pale, light blue light. It casts the shadow of a double cross window into the empty room. The hanging umbrella lamp is switched off.

interpretation

For Dieter Buchhart , Nacht in Saint-Cloud expresses a melancholy “between depression, sadness and depressive mood” that reflects Munch's own emotional world after the death of his father. The emptiness of the room, the darkness, the dissolution of the male figure in the dark of the night, the cross shape thrown into the room by the moonlight - these are all symbols for “death, sadness and loneliness”. The interior serves as a mirror of the human soul, which is separated from the outside world by the window. Such a separation between inner and outer world, symbolized by a window, is found repeatedly in Munch's work, for example in The Kiss or The Sick Child . Ulrich Bischoff describes the interior as a “prison”, a “glass cage” in which people sit like in an aquarium. The picture shows the viewer how “the existence of the human being takes place in his confinement”. For Tone Skedsmo and Arne Eggum , the melancholy and contemplative mood of the picture arises from the contrast between inner reality and the outer world. The man at the window seems to be outside of time and space, but at the same time he is under the impression of his memory images that affect his surroundings. For the first time in Munch's work, death is portrayed as a spiritually empty space.

Hans Dieter Huber describes Nacht in Saint-Cloud as a “transition to a synthetic symbolism ” in Munch's work. Nature is no longer reproduced as it is, but made a reflection of the inner mood. Art should trigger the same emotions in the viewer as in the artist. The person depicted almost merges with the darkness of the room: "He is one with the room and one with his loneliness". The curtain seems to cover the scene and spread "silence about the loneliness of the melancholic". For Alf Bøe, the figure becomes the direct embodiment of the intense melancholy mood of the picture. According to Reinhold Heller, the depiction of the figure sunk in contemplation in the bluish atmosphere of death is both a symbolic depiction of the death of Munch's father and a symbolic depiction of his own melancholy in the winter of 1890. The choice of color of the painting is subject to the influence of the physiologist Charles Henry , who in his color wheel attributed a depressive and melancholic effect to the dominant blue and purple-green colors. Bischoff sees a stylistic similarity of the painting to the Nocturnes by James McNeill Whistler , in which the motif dissolves in the fog. Rodolphe Rapetti points out, however, that Munch could hardly have seen Whistler's Nocturnes beforehand and points to the compositional influence of Edgar Degas' interiors .

Edvard Munch: The Sick Child (1885/86, Norwegian National Gallery, Oslo)

Edvard Munch: The Kiss (1892, Norwegian National Gallery, Oslo)

background

In the autumn of 1889 Edvard Munch traveled to Paris to study the local art scene. He later moved on to Saint-Cloud on the Seine , just a few kilometers outside Paris. The world exhibition gave him the opportunity to gain an overview of contemporary art. In Paris, Munch got to know the works of Gauguin , van Gogh , Toulouse-Lautrec , Caillebottes , Carrières , Ensors , Whistler and the Neo-Impressionists . Initially, his works from this period reflect in particular his exploration of Impressionism , such as various versions of Die Seine near Saint-Cloud or Spring on Karl Johans gate from 1890. During his stay in France, which lasted until 1892, he created but also his first symbolist-expressive pictures, which were formative for his work. Night in Saint-Cloud is the first key image of this new style to be of particular importance.

The Seine at Saint-Cloud (1890, Munch Museum Oslo )

Spring on Karl Johans gate (1890, Bergen Picture Gallery)

The first few months in France were not a happy time for Munch. Munch felt lonely in the French metropolis. At the beginning of December 1889 he learned of the death of his father, who had surprisingly died of a heart attack. A Danish poet named Emanuel Goldstein became his closest friend during those days. He brought Munch closer to the ideas of symbolism and became so much an alter ego for the Norwegian painter that Munch used him as a model for night in Saint-Cloud , a picture in which he depicted his own room and captured his mood at the time. In his diary entries he noted: “How bright it was outside. One would think it was daylight. [...] It is the moon that shines over the Seine. It shines through the window into my room and throws a bluish rectangle on the floor. While I lay there and looked out the window, other images flew past my eyes , vaguely and indistinctly like projections of a magic lantern .

In addition to pictures, important autobiographical and theoretical writings by Munch were created in the winter of 1889/90, such as his so-called Saint Cloud Manifesto , with which he finally rejected impressionism and naturalism and turned to mysticism and symbolism with almost religious fervor : “The People would have to see the holy, the mighty here, and they would take off their hats, like in church. - I want to create a whole series of such images. No more interiors should be painted, no people who read, no women who knit. It would have to be living people who breathe and feel, suffer and love. ”In the spirit of this theoretical manifesto, Reinhold Heller also sees the painting Night in Saint-Cloud as a manifesto of the detachment from a purely external depiction of reality and a turn to art who have favourited symbols to express the subjective state of mind of the artist. It is a symbolization of Munch's motto: "I don't paint what I see, but what I saw."

Provenance, reception and variants

Munch presented Night in Saint-Cloud , at that time still under the simple title Night , for the first time publicly as one of ten paintings at the annual autumn exhibition in the Tivoli of Kristiania, today's Oslo , from October 6th to November 9th, 1890. Bought here The Norwegian doctor, geologist and art collector Fredrik Arentz for 100 crowns, which was only a third of the set price of 300 crowns. In 1917 the Norwegian National Gallery acquired the painting from Arentz's estate.

Munch's “Experiments in a Foreign Environment” were received negatively, and in some cases downright hostile, by domestic criticism, which is bound up with naturalism. Only the art critic Andreas Aubert recognized the importance of Munch's artistic development. He saw in the painter “the embodiment of the 'fourth generation', an era that is obviously about to dawn”. Munch belongs to a “generation of subtle, pathologically sensitive people whom we encounter more and more frequently in the latest art” and who call themselves “'décadents'. as the children of an over-refined, over-civilized age. In the seated figure in the picture Night he recognized “a 'décadent' in the truest sense of the word”: “He lives his life in thought while staring aimlessly out into the dark waters of the Seine, which are gently squandered over so many Closed life. "

An exhibition of the painting in Berlin in 1892 was an initial success for Munch . He received the order for further copies of the picture, four of which he made by 1893, which are privately owned. In one of these variants, the symbolism of death is emphasized even more by reducing the double window cross to a simple cross and by placing a vase with a mandrake on the table . In 1895 Munch returned to the motif once again as part of a drypoint , which for Rapetti shows that the painter was aware of the importance of the early picture for his further development. Nacht in Saint-Cloud also had a formative influence on the so-called “blue painting” of the neo-romantic school in Norway .

literature

- Reinhold Heller: Edvard Munch. Life and work . Prestel, Munich 1993. ISBN 3-7913-1301-0 , pp. 39-47.

- Hans Dieter Huber : Edvard Munch: Dance of Life. Reclam, Stuttgart 2013, ISBN 978-3-15-010937-3 , pp. 41-45.

- Rodolphe Rapetti: Munch and Paris: 1889–1891 . In: Sabine Schulze (Ed.): Munch in France . Schirn-Kunsthalle Frankfurt in collaboration with the Musée d'Orsay, Paris and the Munch Museet, Oslo. Hatje, Stuttgart 1992, ISBN 3-7757-0381-0 , pp. 91-99.

Web links

- Night in St. Cloud, 1890 in the Norwegian National Gallery .

- In the vortex of melancholy . Video lecture by Hans Dieter Huber on YouTube .

Individual evidence

- ↑ a b Ulrich Bischoff : Edvard Munch . Taschen, Cologne 1988, ISBN 3-8228-0240-9 , p. 18.

- ↑ Hans Dieter Huber: Edvard Munch: Dance of Life. Reclam, Stuttgart 2013, ISBN 978-3-15-010937-3 , pp. 43-44.

- ↑ a b c Tone Skedsmo, Arne Eggum : Night in St. Cloud, 1890 . In: Edvard Munch. Museum Folkwang, Essen 1988, without ISBN, cat. 24.

- ↑ Dieter Buchhart (ed.): Edvard Munch. Sign of modernity . Hatje Cantz, Ostfildern 2007, ISBN 978-3-7757-1912-4 , pp. 43-44.

- ^ Ulrich Bischoff: Edvard Munch . Taschen, Cologne 1988, ISBN 3-8228-0240-9 , pp. 18, 20.

- ↑ Hans Dieter Huber: Edvard Munch: Dance of Life. Reclam, Stuttgart 2013, ISBN 978-3-15-010937-3 , pp. 41-43.

- ^ Alf Bøe: Edvard Munch . Bongers, Recklinghausen 1989, ISBN 3-7647-0407-1 , p. 14.

- ↑ a b Reinhold Heller: Edvard Munch. Life and work . Prestel, Munich 1993. ISBN 3-7913-1301-0 , pp. 44, 46.

- ^ Rodolphe Rapetti: Munch and Paris: 1889-1891 . In: Sabine Schulze (Ed.): Munch in France . Schirn-Kunsthalle Frankfurt in collaboration with the Musée d'Orsay, Paris and the Munch Museet, Oslo. Hatje, Stuttgart 1992, ISBN 3-7757-0381-0 , pp. 91, 93.

- ↑ Reinhold Heller: Edvard Munch. Life and work . Prestel, Munich 1993. ISBN 3-7913-1301-0 , pp. 39-43, quotation p. 43.

- ^ Matthias Arnold: Edvard Munch . Rowohlt, Reinbek 1986. ISBN 3-499-50351-4 , p. 36.

- ↑ Reinhold Heller: Edvard Munch. Life and work. Prestel, Munich 1993. ISBN 3-7913-1301-0 , p. 44.

- ↑ Hans Dieter Huber: Edvard Munch: Dance of Life. Reclam, Stuttgart 2013, ISBN 978-3-15-010937-3 , p. 45.

- ^ Night in St. Cloud, 1890 in the Norwegian National Gallery.

- ↑ Reinhold Heller: Edvard Munch. Life and work . Prestel, Munich 1993. ISBN 3-7913-1301-0 , pp. 46-47.

- ^ A b Rodolphe Rapetti: Munch and Paris: 1889-1891 . In: Sabine Schulze (Ed.): Munch in France . Schirn-Kunsthalle Frankfurt in collaboration with the Musée d'Orsay, Paris and the Munch Museet, Oslo. Hatje, Stuttgart 1992, ISBN 3-7757-0381-0 , p. 91.

- ↑ See en: List of paintings by Edvard Munch in the English Wikipedia .

- ↑ Hans Dieter Huber: Edvard Munch: Dance of Life. Reclam, Stuttgart 2013, ISBN 978-3-15-010937-3 , p. 44. See illustration in: Dieter Buchhart (Hrsg.): Edvard Munch. Sign of modernity . Hatje Cantz, Ostfildern 2007, ISBN 978-3-7757-1912-4 , p. 58.

- ↑ Arne Eggum : The meaning of Munch's two stays in France in 1891 and 1892 . In: Sabine Schulze (Ed.): Munch in France . Schirn-Kunsthalle Frankfurt in collaboration with the Musée d'Orsay, Paris and the Munch Museet, Oslo. Hatje, Stuttgart 1992, ISBN 3-7757-0381-0 , p. 112.