Jealousy (munch)

|

| jealousy |

|---|

| Edvard Munch , 1895 |

| Oil on canvas |

| 67 × 100.5 cm |

| Art Museum, Bergen |

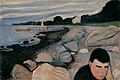

Jealousy (Norwegian: Sjalusi ) is a painting by the Norwegian painter Edvard Munch from 1895. It is part of his life frieze , the compilation of his central works on the subjects of life, love and death. It depicts a constellation of three people who can be deciphered as Stanisław Przybyszewski , his wife Dagny Juel and Munch. While the lovers are reminiscent of the biblical motif of the fall of man , the jealous husband faces the viewer head-on. Munch repeated the theme of jealousy over all of his creative periods in a double-digit number of paintings as well as several graphics and drawings in different constellations and scenarios.

Image description

The composition of Jealousy falls into two almost equal halves. In the left you can see the lovers, in the right a jealous man who looks at the viewer head-on. His pale, strikingly whitish face stands out strongly against the background, in which the brownish upper body and the dark green background, which shows the contours of foliage towards the center, merge into a uniformly dark surface. The man's hair is reddish-brown, his goatee stands out because of the stronger red component, his posture has sunk in, his chin under his shoulders. According to Werner Hofmann, the sky is “pale yellow and heavy”. On the left, a yellow wall divides the motif vertically again. A red flower grows in front of her, which makes Arne Eggum a blood flower .

In the middle of the figure constellation is a blonde woman wearing a bright red cloak that is open at the front and reveals her naked body. According to Werner Hofmann, it resembles “a fruit with a tempting gaping peel”. In fact, her right hand reaches for the red fruit of a tree while her other hand is hidden behind her back. Next to her, facing the woman and thus averted from the viewer in profile, stands a man whose suit is the same brownish color as that of the other man. However, it is framed by a red brushstroke. The couple's faces are merely reddish patches of color without facial features or individual features. A lock of the woman's hair touches her lover.

Biographical background

Munch's painting Jealousy from 1895 is generally regarded as a representation of the triangular relationship between the Polish writer Stanisław Przybyszewski , his wife, the Norwegian writer Dagny Juel , and Edvard Munch himself. The resemblance of Przybyszewski to the face in the foreground with Slavic features is particularly relevant to this assumption contributed. Munch, Przybyszewski and Juel belonged to the bohemian artist that had formed around the restaurant Zum schwarzen Ferkel in Berlin in the early 1890s . Not only Przybyszewski, but also August Strindberg and Munch himself advertised the young Norwegian, who earned the reputation of a femme fatale . Munch painted portraits of all three friends; it is assumed that Dagny Juel was also the model of his repeatedly repeated motif Madonna .

Stanisław Przybyszewski , 1895, 62.5 × 55.5 cm, Munch Museum Oslo

Dagny Juel Przybyszewska , 1893, 158 × 112 cm, Munch Museum Oslo

August Strindberg , 1892, 122 × 91 cm, Moderna Museet Stockholm

Madonna , 1894/95, 90.5 × 70.5 cm, Norwegian National Gallery, Oslo

Even after their marriage in 1893, Przybyszewski and Dagny Juel had an open relationship in which they had numerous extramarital affairs. Arne Eggum assumes that Przybyszewski had a masochistic disposition and used his wife as a template for his literary works, which were often about the subject of jealousy. Munch described the erotic tension that prevailed in the Schwarzer Piglet on some evenings : “I don't understand that my nerves are holding up. I sat at the table and couldn't speak a word. Strindberg spoke. The whole time I thought: Doesn't your husband notice anything? He'll probably turn green at first and then angry. ”It is unknown how close the relationship between Munch and Dagny Juel really was, but in later years he had his painting of her hanging over his bed.

From an exhibition of the picture Jealousy, Munch passed on the anecdote: “I painted some pictures of these people, including one that I called 'jealousy'. It is the picture with the green face in the foreground and a man looking at a naked woman. I had traveled to Paris to hold an exhibition there. Then they came up and I had to leave with my pictures, because they were the two I had painted, him green and she naked. Nothing came of the exhibition in Paris […] This woman's story spoiled a lot for me. "

Przybyszewski's answer to Munch's painting can be read in his key novel Über Bord , which appeared in early 1896. In it he describes the rivalry between two men for a woman, with Munch unmistakably portrayed as Przybyszewski's rival. In the novel, it is Munch who is jealous and cannot get over the fact that Przybyszewski conquers Dagny Juel, so that in the end he takes his own life. In reality, Dagny Juel's life came to a violent end. She was shot by a lover in Tbilisi in 1901 before he killed himself. Munch responded to this news by etching Totes Lovers from the same year.

Dead lovers , etching, 1901, 14.8 × 19.9 cm, Thielska galleriet , Stockholm

interpretation

Symbol of jealousy

For Arne Eggum, Munch's motif points beyond the direct biographical background to a general symbol of jealousy, with which the painter “gave this human feeling general features”. He did not do this with humor, as is traditionally the case with the subject of the horned husband, but with a deadly seriousness that is carried over to the viewer. In particular, the frontality of the jealous has the function of reinforcing the expression. Munch made the first sketches for the motif as early as the winter of 1891/92 and thus before the contact with the Black Piglet scene . So you have roots in Munch's experience that go back a long way. Eggum refers in particular to symbols such as the female hair that reaches for the man (see also Vampire (Munch) #Woman's hair as a symbol ), or the blood flower, which Munch has implemented in many other pictures on the subject of love and love affliction, so in attraction , Detachment and flower of pain . For Ingebjørg Ydstie, jealousy cannot be interpreted without the context of the frieze of life : as a feeling that is an essential part of love. Munch himself put it: “The mystical gaze of the jealous one. In these two piercing eyes, many mirror images are concentrated like in crystal. - The gaze is searchingly interested, full of hatred and loving. An essence of hers that they all have in common. "

Attraction , lithograph, 1896, 45.1 × 35.1 cm, Metropolitan Museum of Art New York

Detachment , 1896, 96 × 127 cm, Munch Museum Oslo

Flower of pain , Indian ink drawing, 50.2 × 32.9 cm, Munch Museum Oslo

Fall of Man

For Arne Eggum, the biblical reference of the scenery is also obvious: The lovers are reminiscent of Adam and Eve in the Garden of Eden . The woman plucks a fruit from the tree of knowledge , he interprets her half-clothed state in this sense as putting on clothes after the shameful reaction to the knowledge of nakedness. According to this interpretation, the figure in the foreground is not just a jealous husband, but God himself, who becomes the witness of the fall of man. In Ingebjørg Ydstie, however, the man's head arouses more associations with Satan than with the Old Testament God. For her, the scene becomes a “travesty of the holy scriptures”, and one reason for choosing Przybyszewski as the man's head could also be seen in his turn to Satanism .

Other versions of the subject

The catalog raisonné by Gerd Woll total lists twelve paintings entitled or title component jealousy , which have emerged from 1895 to 1935, see the list of paintings by Edvard Munch . The later versions repeat the theme of the first painting in different constellations and scenarios. One picture painted between 1898 and 1900 bears the addition of jealousy in the bathroom , and two more from 1929/30 bears the title of jealousy in the garden . Munch also linked the series of motifs The Painter and His Model , edited between 1919 and 1921, in one picture with the subject of jealousy.

Jealousy , 1907, 89 × 82.5 cm, Munch Museum Oslo

Jealousy , 1907, 57.5 × 84.5 cm, Munch Museum Oslo

Jealousy , 1907, 75 × 98 cm, Munch Museum Oslo

Jealousy , 1913, 75 × 98 cm, Städelsches Kunstinstitut , Frankfurt am Main

Jealousy in the Garden , 1929–1930, 100 × 120 cm, Munch Museum Oslo

In 1896 Munch made two lithographs of the painting from 1895. An etching was created in 1914 on the motifs from 1907 and 1913 with the woman dressed in white in the center . Two lithographs from 1930 take up the motif of jealousy in the garden . In the different variations you will always find different jealous men, but they have one thing in common: they stare in front of themselves and have the scene of the lovers in their minds. The female figure, too, breaks away from the model Dagny Juel towards the general type of a strong, self-confident female figure who was both attractive and intimidating to Munch.

Jealousy , lithograph, 1896, 32.6 × 45.6 cm, Thielska galleriet , Stockholm

Tragedy , 1898–1900, 78.1 × 119.3 cm, Minneapolis Institute of Art

Melancholy , 1892 64 × 96 cm, Norwegian National Gallery, Oslo

Red Wild Wine , 1898–1900, 119.5 × 121 cm, Munch Museum Oslo

In a series of motifs titled Three Faces or Tragedy, Munch condensed the motif out of jealousy even further. Only the heads of the people involved can now be seen, a woman's head and an old and a young man's head. Munch implemented the motif in a painting made between 1898 and 1900, in a mezzotint from 1902 and a woodcut from 1913. Between 1891 and 1896, Munch had already created the theme of a triangular relationship in several paintings with melancholy . Here, however, the lovers have moved to the distant perspective of a boat jetty. The motif had the alternative title Jealousy . Even red wine from the years 1898-1900 was as a version of jealousy counted motif,. Again a Stanisław Przybyszewski figure is in the foreground, this time actually with a green-colored face.

literature

- Arne Eggum : Madonna . In: Edvard Munch. Love, fear, death . Kunsthalle Bielefeld, Bielefeld 1980, without ISBN, pp. 101–114.

- Arne Eggum, Guido Magnaguagno: Madonna, around 1894 . In: Edvard Munch . Museum Folkwang, Essen 1988, without ISBN, cat. 42.

- Ingebjørg Ydstie: Jealousy . In: Mara-Helen Wood (ed.): Edvard Munch. The Frieze of Life . National Gallery London, London 1992, ISBN 1-85709-015-2 , pp. 79-81.

Web links

- Edvard Munch in KODE Art Museums with a picture of Jealousy from the Bergen Art Museum.

- Edvard Munch: Jealousy, 1913 in the Städel Art Institute .

Individual evidence

- ↑ a b Werner Hofmann : On an image medium by Edvard Munch . In: fault lines. Essays on 19th Century Art . Prestel, Munich 1979, ISBN 3-7913-0446-1 , pp. 115-116. After: Arne Eggum, Guido Magnaguagno: Madonna, around 1894 . In: Edvard Munch . Museum Folkwang, Essen 1988, without ISBN, cat. 42.

- ↑ a b c d Arne Eggum: Madonna . In: Edvard Munch. Love, fear, death . Kunsthalle Bielefeld, Bielefeld 1980, without ISBN, p. 103.

- ↑ Ingebjørg Ydstie: Jealousy . In: Mara-Helen Wood (ed.): Edvard Munch. The Frieze of Life . National Gallery London, London 1992, ISBN 1-85709-015-2 , p. 79.

- ↑ Arne Eggum, Guido Magnaguagno: Madonna, around 1894 . In: Edvard Munch . Museum Folkwang, Essen 1988, without ISBN, cat. 42.

- ↑ Ingebjørg Ydstie: Jealousy . In: Mara-Helen Wood (ed.): Edvard Munch. The Frieze of Life . National Gallery London, London 1992, ISBN 1-85709-015-2 , pp. 79-81.

- ^ Matthias Arnold: Edvard Munch . Rowohlt, Reinbek 1986. ISBN 3-499-50351-4 , p. 56.

- ↑ Carmen Sylvia Weber (ed.): Edvard Munch. Vampire. Readings on Edvard Munch's Vampire, a key image of the early modern age . Catalog for the Edvard Munch exhibition . Vampire , January 25, 2003 - January 6, 2004, Kunsthalle Würth, Schwäbisch Hall. Swiridoff, Künzelsau 2003, ISBN 3-934350-99-2 , pp. 29, 51.

- ^ Matthias Arnold: Edvard Munch . Rowohlt, Reinbek 1986. ISBN 3-499-50351-4 , p. 57.

- ^ Matthias Arnold: Edvard Munch . Rowohlt, Reinbek 1986. ISBN 3-499-50351-4 , pp. 80, 88.

- ^ Matthias Arnold: Edvard Munch . Rowohlt, Reinbek 1986. ISBN 3-499-50351-4 , pp. 56-57.

- ^ Matthias Arnold: Edvard Munch . Rowohlt, Reinbek 1986. ISBN 3-499-50351-4 , p. 57.

- ↑ Dobbeltselvmord the Munch Museum .

- ↑ Ursula Zeller : The mystery of women: Munch and his female models . In: Johann-Karl Schmidt , Ursula Zeller (Hrsg.): Edvard Munch and his models . Hatje, Stuttgart 1993, ISBN 3-7757-0413-2 , p. 165.

- ↑ a b c d Arne Eggum: Madonna . In: Edvard Munch. Love, fear, death . Kunsthalle Bielefeld, Bielefeld 1980, without ISBN, p. 104.

- ↑ Petra Roettig : “The focus of your art is on graphics”. On Edvard Munch's graphic works . In: Michael Sauer (ed.): Edvard Munch: “… from modern soul life” . Hachmann Edition, Bremen 2006, ISBN 3-939429-03-1 , p. 22.

- ↑ a b Ingebjørg Ydstie: Jealousy . In: Mara-Helen Wood (ed.): Edvard Munch. The Frieze of Life . National Gallery London, London 1992, ISBN 1-85709-015-2 , p. 81.

- ↑ Arne Eggum: Madonna . In: Edvard Munch. Love, fear, death . Kunsthalle Bielefeld, Bielefeld 1980, without ISBN, p. 105.

- ↑ Sjalusi i bathes at Sotheby’s , auction on May 9, 2016.

- ↑ Sjalusi i hagen 1927–1930 in the Munch Museum Oslo .

- ↑ Sjalusi i hagen 1927–1930 in the Munch Museum Oslo .

- ^ Edvard Munch: The Artist and His Model. Jealousy Theme at PubHist.

- ^ Gerd Woll: The Complete Graphic Works . Orfeus, Oslo 2012, ISBN 978-82-93140-12-2 , nos. 68 and 69.

- ↑ Sjalusi I , Sjalusi I and Sjalusi II in the Munch Museum Oslo .

- ^ Gerd Woll: The Complete Graphic Works . Orfeus, Oslo 2012, ISBN 978-82-93140-12-2 , no.471.

- ^ Gerd Woll: The Complete Graphic Works . Orfeus, Oslo 2012, ISBN 978-82-93140-12-2 , nos. 709 and 710.

- ^ Edvard Munch: Jealousy, 1913 in the Städelsche Kunstinstitut , audio file: basic information.

- ^ Gerd Woll: The Complete Graphic Works . Orfeus, Oslo 2012, ISBN 978-82-93140-12-2 , nos. 166 and 465.

- ↑ Reinhold Heller: Edvard Munch. Life and work . Prestel, Munich 1993. ISBN 3-7913-1301-0 , pp. 52-53.

- ^ Arne Eggum: Red Wild Wine, 1898–1900 . In: Edvard Munch . Museum Folkwang, Essen 1988, without ISBN, cat. 50.