Rue Lafayette (Munch)

|

| Rue Lafayette |

|---|

| Edvard Munch , 1891 |

| Oil on canvas |

| 92 × 73 cm |

| Norwegian National Gallery , Oslo |

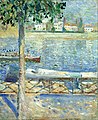

Rue Lafayette (also Rue La Fayette ) is a painting by the Norwegian painter Edvard Munch . It was created in Paris in 1891 during a brief period in which the painter experimented with the stylistic devices of Impressionism before turning to Synthetism , Symbolism and Expressionism . The picture shows a man who looks down from a balcony at the street life of Paris' Rue La Fayette . It experiences its special effect through the quick, oblique brushstrokes and the steep perspective by means of which the viewer looks into the abyss.

Image description

A male figure with a cylinder stands on a balcony and leans over the railing. According to Ulrich Bischoff, it is “representative of the viewer” and directs “the gaze of a stroller ” into the depths. On the left part of the picture you can see house facades and a street crossing lively with horse-drawn carriages and passers-by. They are painted in the technique of pointillism with parallel, diagonal brushstrokes in clear red, blue and yellow. The overall dominant color is blue. Between the application of the oil paint , the primed canvas can be seen again and again , the color of which also contributes to the overall impression of the picture. The angle of the quick, oblique brushstrokes roughly follows the sunlight. Their linear patterns give the impression of movement, of people and carriages pushing forward.

On the right side of the picture, in the representation of the male figure and the balcony, the pointillist painting style is not to be found again. Here straight and curved line patterns that are reminiscent of arabesques are applied with diluted paint . The contours are stronger, the lines more rounded, the colors darker. According to Tone Skedsmo, they give the otherwise luminous and vibrating image “heaviness and stability”. The viewer stands calm and motionless in front of the speed and the crowd on the street. The lines of the balcony railing create a strong sense of depth , the vanishing point of which, according to Reinhold Heller, seems to extend beyond the canvas. While the head of the male figure lies exactly on the "dizzying" escape train on the street, his feet stand on the escape axis of the balcony. The depth of the room dissolves into the light blue-gray of the house shadows.

Image analysis

Munch's "Impressionist Period"

In the autumn of 1889 Edvard Munch traveled to Paris to study the local art scene. He later moved on to Saint-Cloud on the Seine , just a few kilometers outside Paris. The world exhibition gave him the opportunity to gain an overview of contemporary art. In Paris, Munch got to know the works of Gauguin , van Gogh , Toulouse-Lautrec , Caillebottes , Carrières , Ensors , Whistler and the Neo-Impressionists . Initially, his works from this period reflected his exploration of Impressionism, such as Die Seine near Saint-Cloud or Spring on Karl Johans gate from 1890. During his stay in France, which lasted until 1892, he also created his first symbolist-expressive images that were formative for his work, such as the night in Saint-Cloud from 1890 .

The Seine at Saint-Cloud (1890), Munch Museum Oslo

Spring on Karl Johans gate (1890), Bergen Picture Gallery

Munch himself described pictures like Rue Lafayette in retrospect as merely a “brief flicker of my Impressionist period”. In the spring of 1890 he had in the programmatic text Saint-Cloud Manifesto of naturalism renounced and impressionism: "No interior should be painted, no more people who read, no women knitting. It would have to be living people who breathe and feel, suffer and love. ”According to Tone Skedsmo, Munch merely experimented with the technical possibilities offered by Impressionism and Neo-Impressionism and rejected everything that did not help him in the search for a form of expression that suited him .

Inspiration for Rue Lafayette

Munch not only took up Impressionist techniques in the style of Rue Lafayette , but also the motif of a view from an elevated perspective of the city by the urban planner Georges-Eugène Haussmann under Napoleon III. The streets of Paris and the teeming street life had already been explored by Impressionists, for example by Claude Monet in 1873/74 in Boulevard des Capucines . In 1880, Gustave Caillebotte turned his gaze away from the teeming crowd for the first time in Un balcon towards their viewers and their downward gaze. A mirrored perspective that seems to anticipate Munch's composition is shown by Caillebotte's L'Homme au balcon from the same year.

Claude Monet : Boulevard des Capucines (1873/74), Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, Kansas City

Gustave Caillebotte : Un balcon (1880), private collection

Gustave Caillebotte : L'Homme au balcon (1880), private collection

The compositional similarity of Rue Lafayette and Caillebotte's balcony depictions has led to much speculation that Munch must have known the pictures or the painter, and that he even painted his own picture from his apartment on Boulevard Haussmann . In fact, Caillebotte's pictures were never exhibited during Munch's visits to Paris, and there is no evidence of any acquaintance between the two painters. In addition, in 1891 Caillebotte no longer lived on Boulevard Haussmann. Instead, the place from which Munch painted Rue Lafayette can be clearly identified as the hotel at 49 Rue Lafayette, where the painter stayed in April 1891. For example, the forks to Rue Druot and Rue du Faubourg Montmartre can be seen and in the background the towering Opéra Garnier as a blue mass . Oskar Bätschmann locates Munch's balcony on the fifth or sixth floor of the building.

Rodolphe Rapetti suspects that it could have been an influential study on impressionism in Scandinavia by Andreas Aubert in the newspaper Aftenposten from 1883, which influenced Munch for his street scene. At first glance , Aubert described Monet's Boulevard des Capucines as an “irrational mess” that only dissolves from a distance: “The lines start to move like a crowd, the bruises turn into a cab and the yellow becomes Kiosk. [...] Is there madness at play here? In that case the Madness would have method. It's just brilliant. "

Dynamism and abyss

While Reinhold Heller primarily identifies a mood of calm and quiet in the pictures by Monet and Caillebotte, the effect of Rue Lafayette is a completely opposite one of excited dynamics. Munch does not use the technique of pointillism in Rue Lafayette to create a greater luminosity or color harmony, as was the intention of the Neo-Impressionists, but to capture the movement and speed of street life. It is precisely the contrast of the statically painted balcony and man to the diagonal pattern of the brushstrokes that gives the street scene liveliness and dynamism. The depth effect of the vanishing point apparently leading out of the canvas also robs the picture of any calm and static. For Heller, street and balcony do not combine to form a harmonious unit, but the composition breaks down into its elements in terms of content and form.

For Heller, the purpose of the picture, to which all individual elements are subordinate, is a tribute to the mobile life in the modern city, twenty years before the art movement of Futurism was launched. For Karin Sagner , carriages and anonymous pedestrians dissolve into a general movement in Munch, and the image becomes a parable . The unusual fall perspective breaks up the usual view of the city and its residents and stimulates Munch to take a quasi-photographic look, a look of modernity .

Oskar Bätschmann sees Rue Lafayette as more than “just a finger exercise in the Impressionist manner”. In the confrontation of a viewer and the miniature world in front of him, of nearness and distance, Munch arouses feelings of alienation, abyss and danger. And for the first time in his work he developed two ciphers that were to become formative for later, more important works: melancholy and despair, which are expressed through the figure of a melancholy viewer and the frenzied perspective. Images like Despair and The Scream also use these ciphers.

Despair (1892), Thielska galleriet , Stockholm

Despair (1894), Munch Museum Oslo

The Scream (1893), Norwegian National Gallery

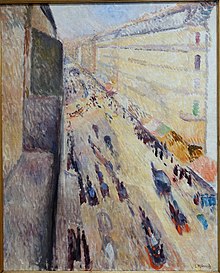

Counter-image: Rue de Rivoli

Munch took up the composition and painting technique of Rue Lafayette in a second picture from 1891, a representation of the Parisian Rue de Rivoli . In the mirrored perspective, the diagonal no longer leads upwards, but rather, according to Ulrich Bischoff, “with almost dramatic speed downwards”. The balcony on which the viewer is located forms a wall of green and purple rectangles on the left edge of the picture, which seem to be tilting forward. The steep line of streets and houses leaves only a small triangle of blue sky free. Street life itself is depicted with strong abstraction : in the foreground passers-by and carriages are painted as spots of color, in the background they become a multitude of pointillist points.

As in Rue Lafayette , according to Tone Skedsmo, Munch was also fascinated by the "'infinity' of the Parisian streets" in Rue de Rivoli . For Bischoff, both pictures are part of a “calm and undisturbed island” compared to the “frighteningly swirling” oeuvre that Munch created in the 1890s (cf. for example the frieze of life ).

Reception and provenance

The French photographer Constant Puyo made explicit reference to the composition of Munch's Rue Lafayette in his photograph Montmartre , published in 1906 . It shows a maid leaning over a balcony parapet in the attic of a house on Montmartre in Paris to look down.

Constant Puyo : Montmartre (1906)

The Norwegian National Gallery acquired Rue Lafayette in 1933 with a donation from the art collector and patron Olaf Schou.

literature

- Oskar Bätschmann : Distance from nature. Landscape painting 1750–1920 . DuMont, Cologne 1989, ISBN 3-7701-2193-7 , pp. 144-148.

- Ulrich Bischoff : Edvard Munch . Taschen, Cologne 1988, ISBN 3-8228-0240-9 , pp. 22-24.

- Reinhold Heller: Edvard Munch. Life and work . Prestel, Munich 1993. ISBN 3-7913-1301-0 , pp. 48-49.

- Reinhold Heller: Edvard Munch: The Scream . Allen Lane The Penguin Press, London 1973 ISBN 0-7139-0276-0 , pp. 62-65.

- Rodolphe Rapetti: Munch and Paris: 1889–1891 . In: Sabine Schulze (Ed.): Munch in France . Schirn-Kunsthalle Frankfurt in collaboration with the Musée d'Orsay, Paris and the Munch Museet, Oslo. Hatje, Stuttgart 1992, ISBN 3-7757-0381-0 , pp. 104-106.

- Tone Skedsmo: Rue Lafayette, 1891 . In: Edvard Munch . Museum Folkwang, Essen 1988, without ISBN, cat. 23.

Web links

- Rue Lafayette, 1891 in the Norwegian National Gallery .

- Karin Sagner : Caillebotte, Munch and the modern composition . In: Schirn Mag from October 1, 2012.

Individual evidence

- ↑ a b c d Ulrich Bischoff : Edvard Munch . Taschen, Cologne 1988, ISBN 3-8228-0240-9 , p. 24.

- ↑ a b c Reinhold Heller: Edvard Munch: The Scream . Allen Lane The Penguin Press, London 1973 ISBN 0-7139-0276-0 , p. 62.

- ↑ a b c d e f g Tone Skedsmo: Rue Lafayette, 1891 . In: Edvard Munch . Museum Folkwang, Essen 1988, without ISBN, cat. 23.

- ^ Rodolphe Rapetti: Munch and Paris: 1889-1891 . In: Sabine Schulze (Ed.): Munch in France . Schirn-Kunsthalle Frankfurt in collaboration with the Musée d'Orsay, Paris and the Munch Museet, Oslo. Hatje, Stuttgart 1992, ISBN 3-7757-0381-0 , p. 104.

- ↑ a b c d Oskar Bätschmann: Distance from nature. Landscape painting 1750–1920 . DuMont, Cologne 1989, ISBN 3-7701-2193-7 , p. 144.

- ↑ a b c d e f Reinhold Heller: Edvard Munch. Life and work. Prestel, Munich 1993. ISBN 3-7913-1301-0 , p. 48.

- ^ Rodolphe Rapetti: Munch and Paris: 1889-1891 . In: Sabine Schulze (Ed.): Munch in France . Schirn-Kunsthalle Frankfurt in collaboration with the Musée d'Orsay, Paris and the Munch Museet, Oslo. Hatje, Stuttgart 1992, ISBN 3-7757-0381-0 , p. 105.

- ↑ a b Rue Lafayette, 1891 in the Norwegian National Gallery .

- ^ Oskar Bätschmann: Distance from nature. Landscape painting 1750–1920 . DuMont, Cologne 1989, ISBN 3-7701-2193-7 , p. 148.

- ^ Tone Skedsmo, Arne Eggum : Night in St. Cloud, 1890 . In: Edvard Munch. Museum Folkwang, Essen 1988, without ISBN, cat. 24.

- ^ Matthias Arnold: Edvard Munch . Rowohlt, Reinbek 1986. ISBN 3-499-50351-4 , p. 36.

- ^ Reinhold Heller: Edvard Munch: The Scream . Allen Lane The Penguin Press, London 1973 ISBN 0-7139-0276-0 , p. 64.

- ^ Rodolphe Rapetti: Munch and Paris: 1889-1891 . In: Sabine Schulze (Ed.): Munch in France . Schirn-Kunsthalle Frankfurt in collaboration with the Musée d'Orsay, Paris and the Munch Museet, Oslo. Hatje, Stuttgart 1992, ISBN 3-7757-0381-0 , pp. 104-105.

- ↑ See, for example, a current photo of the balcony of the Hotel Jules at 49 Rue Lafayette on arteeblog.com and position on Google Street View .

- ^ Rodolphe Rapetti: Munch and Paris: 1889-1891 . In: Sabine Schulze (Ed.): Munch in France . Schirn-Kunsthalle Frankfurt in collaboration with the Musée d'Orsay, Paris and the Munch Museet, Oslo. Hatje, Stuttgart 1992, ISBN 3-7757-0381-0 , p. 105.

- ^ Rodolphe Rapetti: Munch and Paris: 1889-1891 . In: Sabine Schulze (Ed.): Munch in France . Schirn-Kunsthalle Frankfurt in collaboration with the Musée d'Orsay, Paris and the Munch Museet, Oslo. Hatje, Stuttgart 1992, ISBN 3-7757-0381-0 , pp. 105-106.

- ↑ a b Karin Sagner: Caillebotte, Munch and the modern composition . In: Schirn Mag from October 1, 2012.

- ^ Oskar Bätschmann: Distance from nature. Landscape painting 1750–1920 . DuMont, Cologne 1989, ISBN 3-7701-2193-7 , pp. 144-148.

- ↑ Rue de Rivoli at harvardartmuseums.org.