Marat's death

|

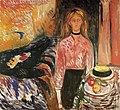

| Marat's death I |

|---|

| Edvard Munch , 1907 |

| Oil on canvas |

| 150 × 199 cm |

| Munch Museum Oslo |

|

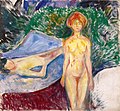

| Marat's death II |

|---|

| Edvard Munch , 1907 |

| Oil on canvas |

| 153 × 148 cm |

| Munch Museum Oslo |

Marats Tod (Norwegian: Marats død ), also called The Death of Marat , is a picture motif by the Norwegian painter Edvard Munch , which he executed in three paintings and a lithograph in 1906 and 1907 . In it, Munch linked a personal experience, an argument with his lover Tulla Larsen, during which Munch was shot and lost a finger joint, with a historic event, the murder of Jean Paul Marat , one of the leading figures of the French Revolution , by Charlotte Corday . Munch had a known forerunner in Jacques-Louis David's history painting The Death of Marat from 1793. The main works of his subject are two paintings known as Marat's Death I and Marat's Death II . Created over a period of six months, they document a clear change in Munch's painting style.

Image description

Marat's Death I shows an interior in a room with green walls. A man, who can easily be recognized as Edvard Munch's alter ego , is stretched out naked on a white sheet covered with blood stains. The bed forms an angle to the image plane, so that the strong perspective foreshortening, according to Arne Eggum and Zissel Biørnstad leads to an "aggressive diagonals". The woman in the foreground, who bears Tulla Larsen's features, is also naked and facing the viewer head-on. It stands still, as if it had frozen into a pillar of salt . The lower right corner is occupied by a round table on which there is a lady's hat and a fruit basket. The painting style is a strong impasto reminiscent of Fauvism , in which the pastose colors are applied very thickly, so that a relief-like structure is retained in which one can recognize brushstrokes, for example.

Marat's Death II is implemented using a different painting technique. The basic elements, the lying naked man on the bed and the rigidly standing woman facing the viewer, are the same. This time, however, the vertical female figure and the horizontal bed form a right angle. According to Barbara Schütz, the shaped blocks ensure static stability, while the brushwork creates unrest in the picture. The colors are applied in lines across the entire picture, with the lines varying greatly in length and width. The motif is geometrized in such a way that, according to Schütz, the result is a "nervous, coarse-meshed, in places [...] torn color texture". The colors are strong and are determined by the complementary color combinations green and red as well as yellow and blue. In Munch's own words, this technique is about "breaking up surfaces and lines ... with extremely wide, often meter-long lines or vertical [,] horizontal and diagonal brushstrokes".

interpretation

Munch often painted multiple versions of the same subject. Usually they all have the same title and are not numbered. Therefore, for Arne Eggum and Sissel Biørnstad, the attached Roman numerals are a conscious reference to the well-known predecessor of the same name, The Death of Marat by Jacques-Louis David , from which Munch wanted to stand out. An obvious difference between the two pictures is that in David's picture only the dying Marat is depicted and there is no trace of his murderer, while in Munch she is the focus and dominates the action.

Jacques-Louis David : The Death of Marat (1793), oil on canvas, 162 × 128 cm, Royal Museums of Fine Arts , Brussels

For Michael Glover, the portrayal in Marat's Death I is “an emotional maelstrom ” in which everything from the vortex of the lines, the scarred brush marks to the irrational colors collapses on the viewer with great liveliness and violence. Nevertheless, the female figure in the center, who is the outcome of the event, radiates a calm and indifference that does not seem to be from this world. In its thin, pale, enervating beauty it is more reminiscent of a spirit that seems to float towards the viewer. It casts a large, ominous shadow on the wall, suggesting that things are not what they seem. The body of the dead, on the other hand, appears roughly and lovelessly moved to the side like a discarded doll.

As in many of Edvard Munch's works, according to Michael Glover, Marat's Death is about the battle of the sexes and the terrible, vampiric unpredictability of the feminine, which is as seductive as it is frightening. Thomas W. Gaehtgens describes Munch's variation on the Marat theme as a "parable of the cruel, existential war between the sexes". Arne Eggum and Sissel Biørnstad see the destructive power of women over men as a theme that runs through his entire work. Matthias Arnold considers the “woman murdering men” to be Munch's “central psychological problem”, which grew into a crisis around the time the paintings were made with paranoid fears, obsessions and a form of midlife crisis, which repeatedly resulted in heavy alcohol consumption and aggressive behavior Failures train broke.

Autobiographical background

In 1898 Edvard Munch met Mathilde, known as "Tulla", Larsen, the six years younger daughter of a wealthy Norwegian wine merchant. In the following years the artist spent some of his summer stays in Norway at Larsen's side and also took her on trips abroad. The relationship was problematic, however, Matthias Arnold speaks of a love-hate relationship: Munch, who already had a difficult relationship with women, felt erotically attracted to the young, possessive woman, but at the same time oppressed and robbed of his freedom. Tulla Larsen was often referred to as Munch's fiancée, wedding plans were made, even if Munch claimed in retrospect that only Larsen had spoken of an engagement and that he had never had any plans to marry. The relationship reached its dramatic climax and end in 1902 when, in an unsettled argument, possibly after a staged suicide attempt, a gunshot from a revolver (although it is not known whose hand it was in) and Munch came on top Lost the limb of his left middle finger.

Tulla Larsen (1898/99), oil on canvas, 119.5 × 61 cm, Munch Museum Oslo

Self-portrait with Tulla Larsen (1905), oil on canvas, 64 × 45.5 and 62 × 33 cm, Munch Museum Oslo

On the operating table (1902/03), oil on canvas, 109 × 149 cm, Munch Museum Oslo

According to Arne Eggum and Sissel Biørnstad, the event that took place in his holiday home in Åsgårdstrand left deep scars on the painter. According to the clinic's records, Munch insisted on local anesthesia for the following operation regardless of his pain in order to be able to follow the treatment. He recorded his impressions in the painting On the Operating Table from 1902/1903. The picture became the starting point for the numerous variations on the theme that he was to create in the following years, including the motif of Marat's death . As part of the treatment, an X-ray of Munch's hand with the sphere was taken, which is in the possession of the Munch Museum in Oslo and is also on display.

Even if Munch only needed his left hand to hold the palette while painting, the mutilated finger and constant pain reminded him of what was happening throughout his life and his fear of the dangerousness of the feminine was confirmed. In a letter to his friend Jappe Nilssen in 1908/09, Munch wrote: “I understand that no one at home has seen or understood the vile actions of a rich social girl who no longer wants to live with her mother and who believes is that at the age of 30 the young girl days are over, are capable - and that his takers and pimps ... were willing to dig the grave I fell into - because they wrote the play that was supposed to destroy me ... It hit me right in the middle into the heart. "

Origin and work context

The events of 1902 preoccupied Munch for many years. From 1905 on he made various drawings, lithographs and paintings in which he lies bleeding in bed in his summer house in Åsgårdstrand, while Tulla Larsen stands by. In the foreground is a table with a book, a glass, a straw hat or a bowl of fruit. These accessories, which can also be found in Marat's death , actually played a role in the dispute in 1902, according to Munch's notes. Munch gave the pictures titles such as Mord or Die Mörderin , see the list of paintings by Edvard Munch . In 1907 he exhibited one of the pictures in Berlin under the title Still Life: The Murderess . Munch's famous saying, with which he set his style apart from the well-known role model, is likely to refer to this picture: "I painted a still life just like Cézanne , only that I painted a murderess and her victim in the background."

Murder (1906), oil on canvas, 69.5 × 100 cm, Munch Museum Oslo

The Murderess (1906), oil on canvas, 110 × 120 cm, Munch Museum Oslo

The Murderess (1907), oil on canvas, 89 × 63 cm, Munch Museum Oslo

Marat's Death (1906/07), oil on canvas, 70 × 76 cm, Munch Museum Oslo

A first version, in which Munch linked his personal experience with the historical event of the murder of Jean Paul Marat by Charlotte Corday , was written in 1906/07. According to Anni Carlsson, he increased his own experience in the motif by “appropriating a mythical-historical situation”. For Reinhold Heller, a “personal mythology” takes the place of “the factual” in the pictures. Munch eschewed all the specific details of the real events and completely bared his protagonists. Marat's Death I was written in Berlin in spring 1907, and Marat's Death II six months later in Warnemünde . According to the inscriptions, Munch was already working on a lithograph of the motif in 1904/05. Gerd Woll considers such an early completion to be unlikely and gives the date of origin 1906/07 for the lithograph as well.

Working on the motif that was close to him personally made Munch feel exhausted and drained. He reported to his friend Christian Gierløff: “My and my beloved virgin child [the phrase is an allusion to Ibsen’s drama Hedda Gabler , with whose heroine Munch Tulla Larsen identified]“ Marat's death ”(I had this idea for 9 years) - this is a painting that took a lot of strength. By the way, I don't see it as a major work, more as an experiment. You are welcome to tell the enemy that the child is now born and baptized. It hangs in L'Indépendant . "He wrote to his patron Ernest Thiel :" It takes a long time before you can regain your strength after this picture. "

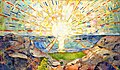

According to Reinhold Heller, many of the motifs of the frieze of life play into Marat's death and were repeated by Munch in a “more garish, tormented scene”, for example the dominant female figure in vampire and ashes with a comparable frozen pose. Munch repeated the style of the broad horizontal and vertical strokes of Marat's Death II , called “experiment”, in several other pictures, for example in Amor and Psyche (1907) and in Self-Portrait in the Clinic (1909). Munch also made use of this “strip technique” in the monumental painting Die Sonne (1911) for the auditorium of the University of Kristiania . The obsession triggered by Tulla Larsen and the events of 1902, however, Munch had successfully exorcised with the Marat pictures. In 1908 he felt full of new energy again. Not until 1930 did he return to the figures Corday and Marat (the latter now sitting in the bathroom) with a series of drawings, paintings and a lithograph.

Vampire (1893), oil on canvas, 80.5 × 100.5 cm, Kunstmuseum, Göteborg

Asche (1895), oil on canvas, 120.5 × 141 cm, Norwegian National Gallery , Oslo

Amor and Psyche (1907), oil on canvas, 119.5 × 99 cm, Munch Museum Oslo

The Sun (1911), oil on canvas, 455 × 780 cm, University of Oslo

literature

- Matthias Arnold: Edvard Munch. Rowohlt, Reinbek 1986. ISBN 3-499-50351-4 , pp. 100-101.

- Anni Carlsson: Edvard Munch. Life and work. Belser, Stuttgart 1989, ISBN 3-7630-1936-7 , pp. 69-71.

- Arne Eggum , Sissel Biørnstad: The Death of Marat I. In: Mara-Helen Wood (ed.): Edvard Munch. The Frieze of Life. National Gallery London, London 1992, ISBN 1-85709-015-2 , pp. 131-132.

- Reinhold Heller: Edvard Munch. Life and work. Prestel, Munich 1993. ISBN 3-7913-1301-0 , pp. 118-119.

- Barbara Schütz: Marat's Death II, 1907. In: Edvard Munch. Museum Folkwang, Essen 1988, without ISBN, cat. 77.

Web links

- Marat's Death I (1907) at the Munch Museum Oslo

- Marat's Death II (1907) at the Munch Museum Oslo

- Marat's death (1906-07) at the Munch Museum, Oslo

- Marat's Death (lithograph, 1906-07) at the Munch Museum Oslo

Individual evidence

- ↑ a b Arne Eggum, Sissel Biørnstad: The Death of Marat I. In: Mara-Helen Wood (ed.): Edvard Munch. The Frieze of Life. National Gallery London, London 1992, ISBN 1-85709-015-2 , pp. 131-132.

- ^ Barbara Schütz: Marat's Death II, 1907. In: Edvard Munch. Museum Folkwang, Essen 1988, without ISBN, cat. 77.

- ↑ a b c Anni Carlsson: Edvard Munch. Life and work. Belser, Stuttgart 1989, ISBN 3-7630-1936-7 , p. 69.

- ↑ a b c Arne Eggum, Sissel Biørnstad: The Death of Marat I. In: Mara-Helen Wood (ed.): Edvard Munch. The Frieze of Life. National Gallery London, London 1992, ISBN 1-85709-015-2 , p. 131.

- ↑ a b c Michael Glover: Great Works: The Death of Marat, 1907 (150x200cm) Edvard Munch . In: The Independent from a. April 2011.

- ↑ Thomas W. Gaehtgens : Davids Marat (1793) or the dialectic of the victim . In: Kritische reports 2/2008, p. 78 ( PDF file ).

- ^ Matthias Arnold: Edvard Munch. Rowohlt, Reinbek 1986. ISBN 3-499-50351-4 , pp. 100-102.

- ^ Matthias Arnold: Edvard Munch. Rowohlt, Reinbek 1986. ISBN 3-499-50351-4 , pp. 88-89.

- ↑ Reinhold Heller: Edvard Munch. Life and work. Prestel, Munich 1993. ISBN 3-7913-1301-0 , p. 102.

- ^ Matthias Arnold: Edvard Munch. Rowohlt, Reinbek 1986. ISBN 3-499-50351-4 , pp. 90-91.

- ^ Sue Prideaux: The soul laid bare. Edvard Munch at Tate Modern I . On the Tate Gallery website , August 27, 2012.

- ^ Matthias Arnold: Edvard Munch. Rowohlt, Reinbek 1986. ISBN 3-499-50351-4 , pp. 91-92.

- ↑ a b c d Reinhold Heller: Edvard Munch. Life and work. Prestel, Munich 1993. ISBN 3-7913-1301-0 , p. 118.

- ↑ a b Arne Eggum, Sissel Biørnstad: The Death of Marat I. In: Mara-Helen Wood (ed.): Edvard Munch. The Frieze of Life. National Gallery London, London 1992, ISBN 1-85709-015-2 , p. 132.

- ^ Matthias Arnold: Edvard Munch. Rowohlt, Reinbek 1986. ISBN 3-499-50351-4 , p. 42.

- ^ The Death of Marat II at Google Arts & Culture .

- ^ Marats død in the Norwegian National Gallery .

- ^ The Death of Marat (Marats død) at the Museum of Modern Art .

- ^ Gerd Woll: The Complete Graphic Works. Orfeus, Oslo 2012, ISBN 978-82-93140-12-2 , no.287.

- ^ Matthias Arnold: Edvard Munch. Rowohlt, Reinbek 1986. ISBN 3-499-50351-4 , pp. 100-101.

- ↑ Iris Müller-Westermann: Self Portrait in Copenhagen . In: Mara-Helen Wood (ed.): Edvard Munch. The Frieze of Life . National Gallery London, London 1992, ISBN 1-85709-015-2 , pp. 134-135.

- ↑ Simon Maurer: The sun, 1912. In: Edvard Munch. Museum Folkwang, Essen 1988, without ISBN, cat. 90.

- ↑ Reinhold Heller: Edvard Munch. Life and work. Prestel, Munich 1993. ISBN 3-7913-1301-0 , p. 119.

- ↑ Charlotte Corday , Marat i badekaret and Charlotte Corday , Marat i badekaret and Charlotte Corday at the Munch Museum Oslo .