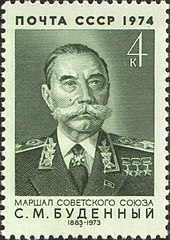

Semyon Mikhailovich Budyonny

Semjon Michailowitsch Budjonny ( Russian Семён Михайлович Будённый , scientific transliteration Semën Michajlovič Budënnyj , ; * April 13th jul. / April 25th 1883 greg. In Kozjurin in the Oblast of Don-He † Donskowo Oblast ; October 26, 1973 in Moscow ) was a Marshal of the Soviet Union , Chief Inspector of the Red Army and three-time Hero of the Soviet Union (1958, 1963, 1968).

Life

youth

Semjon Budjonny was born in 1883 as the son of poor farmers in the Don Cossack area and joined the tsarist army in 1903 . From 1904 to 1905 he took part in the war against Japan . During World War I he was a sergeant in a regiment of the Tsarist dragoons , decorated with the highest Russian Order of St. George .

Civil war, cavalry inspector

In the Russian Civil War from 1918 to 1921 Budjonny led larger cavalry formations . He fought at the head of the 1st Red Cavalry Army in the 10th Army against Anton Denikin , general of the White Guard troops , and in 1920 drove the Cossacks from Yekaterinodar . Budjonny's cavalry brigade was involved in pogroms against Jews in the Polish-Ukrainian border region at this time .

He was also involved in the Polish-Soviet War of 1920 as the commander of an army . During this time his friendship with the rising general secretary of the CPSU Josef Stalin, which endured all crises, was founded . Although he never held a higher position in the party, he was always a confidante of Stalin. He liked Budjonny's simple way of life, his virtuoso playing on the harmonica and his role as "mood cannon" at meetings in the closest circle. Budyonny formed together with Kliment Voroshilov a "military opposition" to the then undisputed military leader and founder of the Red Army Leon Trotsky in the beginning power struggle between Stalin and Trotsky.

From 1924 to 1937 Budjonny was the inspector of the cavalry troops. The existence of the Red Cavalry up to the beginning of the 1950s is owed to the principles of the operational and tactical use of cavalry in connection with lightly armored units, which were tried and tested there. On November 20, 1935, he was appointed Marshal. In 1938 he became a member of the Central Committee of the CPSU. He was one of the military judges in the fourth Moscow trial of 1937 against Marshal Mikhail Tukhachevsky , who was sentenced to death as part of the Stalin purges .

Second World War

In the Second World War Budjonny initially held high positions in the Red Army. In 1941 he was Commander-in-Chief of the "Strategic Southwest Direction", to which the Southwest Front and the South Front in Ukraine were subordinate. During the Battle of Kiev in August / September 1941, he repeatedly demanded permission from Stalin and his high command to vacate the front arch on the Dnepr , which protruded far to the west , since otherwise he considered a disaster in the form of the encircling of his troops to be inevitable. He had already criticized the leadership of the high command in the days before. On September 12, 1941, he was therefore released from his command and replaced by Marshal Semyon Tymoshenko . In fact, just three days later the southwest front was encircled and most of it was wiped out. Stalin let Budyonny fly out of the cauldron. However, he immediately received the vacant post of Commander-in-Chief of the Reserve Front in front of Moscow. This front was disbanded on October 10, 1941, during the battles at Vyazma and Brjansk , which were also loss-making . In the Battle of Moscow at the end of 1941, he commanded an army south of Moscow around Malojaroslavets .

Until mid-1942 he was Commander-in-Chief of the North Caucasus Front , his political officer was Lasar Kaganowitsch . The German Wehrmacht was able to successfully push back its army units. Budjonny was again relieved of his last, unsuccessful front line command.

Despite his defeats, Stalin stayed with him. Since January 1943 he was inspector of the cavalry of the Red Army and was honored as its founder in many ways.

In 1946 he was elected to the Supreme Soviet .

Others

Horse breeding

Budjonny made great contributions to Russian horse breeding when, in 1921, contrary to a decree by Lenin that prohibited all private ownership of horses and dissolved all state studs, he gave the order to re-establish state studs. Some breeds, such as the Orlov-Rostopchin and the Strelezker, were already extinct at this point, and much of the quality had been lost in all of them. As the leader of the Don Cossacks , the preservation of the Don horse in particular , but also the Kabardines , Ukrainians and Terskans, goes back to his energetic commitment to high-quality horse breeding. As a “horse understanding” Budjonny was considered an authority. In addition, he initiated the establishment of a new breed according to his ideas, which got his name - Budjonny .

family

Budjonny was married three times: His first wife Nadezhda is said to have committed suicide in the early 1930s. His second wife, Olga, was a soprano. Around 1937, the GPU secret police investigated her for speaking the French language . She was arrested offstage during a concert and was not rehabilitated until 1955. His third wife was called Maria. His daughter Nina managed his memoirs and many unpublished notes, which provided interesting insights into the Stalin era.

Honors

- In the GDR , the Polytechnic High School in Dorfchemnitz near Sayda and the 4th Polytechnic High School Berlin-Treptow were called Budjonnys.

- The North Caucasian city Prikumsk was in 1935 Budyonnovsk renamed.

- Isaak Babel's novel Die Reiterarmee ( The Cavalry Army) helped to achieve literary fame with his description of the Red Cavalry Army led by Budjonny.

- In his honor, the song The Red Cavalry ( Konarmejskaya ) and the Budyonny March were composed in the USSR .

- The Budjonowka was a woolen headgear in the Red Army, which was worn from 1918 to around 1940 and was named after Budjonny.

- Budjonny was - as usual in the USSR - bearer of many orders, including Hero of the Soviet Union (3 ×), Order of Lenin (8 ×), Order of the Red Banner (6 ×) and the Order of Suvorov .

- He was featured on postage stamps of the USSR from 1938 and 1974.

- The Telecommunications Force Military Academy in St. Petersburg has been called SM Budjonny since 1946

- In 1985, Vladimir Lyubomudrow filmed the life and work of Budyonny during the Russian Revolution under the title The First Cavalry Army .

- There is a cruise ship of his name: Semyon Budyonnyy .

Works

- About Lenin's military activities in the intervention and civil war 1918-1920 (together with Semyon Aralov). Publishing house of the Ministry for National Defense, Berlin 1957.

- Red riders ahead. German military publisher, Berlin 1961.

Web links

- Literature by and about Semjon Michailowitsch Budjonny in the catalog of the German National Library

- Newspaper article about Semjon Michailowitsch Budjonny in the 20th century press kit of the ZBW - Leibniz Information Center for Economics .

Individual evidence

- ↑ Christoph Dieckmann: Jewish Bolshevism 1917 to 1921 . In: Holocaust und Genölkermorde , edited by Sybille Steinbacher , Frankfurt / New York 2012, pp. 55–83, p. 61.

- ^ John Erickson: The Road to Stalingrad , London 2003, pp. 207f

- ^ Photos of the prosecution

- ↑ Telephone book East Berlin 1989 , p. 506.

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Budyonny, Semyon Mikhailovich |

| ALTERNATIVE NAMES | Будённый, Семён Михайлович (Russian) |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | Marshal of the Soviet Union, three times Hero of the Soviet Union |

| DATE OF BIRTH | April 25, 1883 |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | at Voronezh |

| DATE OF DEATH | October 26, 1973 |

| Place of death | Moscow |